Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho

versão On-line ISSN 1984-6657

Rev. Psicol., Organ. Trab. vol.21 no.2 Brasília abr./jun. 2021

The development process of a measure of democratic culture in organizations

Processo de desenvolvimento de uma medida de cultura democrática nas organizações

El proceso de desarrollo de una medida de cultura democrática en las organizaciones

Lucas Barrozo de AndradeI ; Natasha AlvarezII

; Natasha AlvarezII ; Diego MoraesIII

; Diego MoraesIII ; Wayson MaturanaIV

; Wayson MaturanaIV ; Anna Carolina PortugalV

; Anna Carolina PortugalV ; Jesus Landeira-FernandezVI

; Jesus Landeira-FernandezVI ; Luis AnunciaçãoVII

; Luis AnunciaçãoVII

IUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brasil

IIInstituto Sivis, Brasil

IIIInstituto Sivis, Brasil

IVPontifícia Universidade Católica - Rio (PUC-Rio), Brasil

VUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brasil

VIPontifícia Universidade Católica - Rio (PUC-Rio), Brasil

VIIPontifícia Universidade Católica - Rio (PUC-Rio), Brasil

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The development of a psychometric measure for assessing democratic culture in organizations is described.

METHODS: Two studies were conducted. A literature review of studies reporting democratic culture instruments was undertaken. Six databases were used within the timeframe of between 2015 and 2020. Four specialists rated the derived items on clarity, relevance, and translation via the content validity coefficient (CVC). An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with 225 individuals and the internal consistency was evaluated by Cronbach's alpha.

RESULTS: A set of 2,049 articles were obtained in the literature review. The content validity coefficient allowed us to gather 96 items. The EFA achieved a final multidimensional solution formed of 58 items in 6 correlated factors: Citizen Participation, Tolerance and Openness, Organizational Citizenship, Traditionalist Dogmatism, Individualism and Rebellion, and Punitive Authoritarianism. Cronbach's alpha ranged from .59 to .78.

CONCLUSION: This article presented several procedures used to develop a new measure of democratic culture in organizations.

Keywords: democratic culture, assessment, psychometrics.

RESUMO

Este trabalho visa o desenvolvimento de uma medida psicométrica para avaliação da cultura democrática em organizações.

MÉTODOS: Dois estudos foram realizados. No primeiro, uma revisão de literatura com estudos que usaram instrumentos de cultura democrática foi realizada. Seis bases de dados foram usadas entre 2015 e 2020. Quatro especialistas avaliaram os itens derivados quanto à clareza, relevância e tradução por meio do Coeficiente de Validade de Conteúdo (CVC). Uma Análise Fatorial Exploratória (AFE) foi realizada com 225 indivíduos e a consistência interna foi avaliada pelo alfa de Cronbach.

RESULTADOS: 2.049 artigos foram obtidos na revisão. O CVC nos permitiu reunir 96 itens. A EFA alcançou uma solução multidimensional formada por 58 itens em seis fatores correlacionados de Participação Cidadã, Tolerância e Abertura, Cidadania Organizacional, Dogmatismo Tradicionalista, Individualismo e Rebelião, Autoritarismo Punitivo. O alfa de Cronbach variou de 0,59 a 0,78.

CONCLUSÃO: Este artigo apresentou procedimentos usados para desenvolver uma nova medida de cultura democrática.

Palavras-chave: cultura democrática, avaliação, psicometria.

RESUMEN

OBJETIVO: El objetivo de este trabajo fue describir el desarrollo de una medida psicométrica para la evaluación de la cultura democrática en organizaciones.

MÉTODOS: Se realizaron dos estudios: una revisión de la literatura de estudios que informan sobre instrumentos de cultura democrática, en seis bases de datos, en el período de 2015 a 2020, en la cual cuatro especialistas calificaron los elementos derivados según su claridad, relevancia y traducción con base en el coeficiente de validez del contenido (CVC); y un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio (AFE) con 225 individuos en que se evaluó la consistencia interna utilizando el Alfa de Cronbach.

RESULTADOS: Se obtuvo un conjunto de 2 049 artículos en la revisión de la literatura; el CVC permitió reunir 96 elementos; la EFA logró una solución multidimensional conformada por 58 ítems en 6 factores correlacionados de Participación Ciudadana, Tolerancia y Apertura, Ciudadanía Organizacional, Dogmatismo Tradicionalista, Individualismo y Rebelión y Autoritarismo Punitivo; y el Alfa de Cronbach osciló entre 0,59 y 0,78.

CONCLUSIÓN: Este artículo presentó procedimientos utilizados para desarrollar una nueva medida de cultura democrática.

Palabras clave: cultura democrática, evaluación, psicometría.

Political science literature and data has documented for a long time the problem of Brazilian democratic culture (Baquero, 2003; Meneguello, 2006; Moisés, 2008). Latinobarómetro's 2018 results, for example, showcase that only 4% of Brazilians trust others (Latinobarómetro, 2018). The Local Democracy Index, a tool used to measure the quality of democracy in cities, indicates low adherence to democratic values in the cities of Curitiba and São Paulo, with 90% of Curitibanos arguing that most people, rarely or only sometimes obey the laws and 60% of the interviewed Paulistanos affirming not to know any political institution or mechanism of popular influence (Instituto Sivis, 2018, 2019). Known as a flawed democracy, a country with free and fair elections, but with an insufficient political culture and reduced popular participation, Brazil occupies the forty-ninth position with a score of 6,92 points out of ten in the Economist Intelligence Unit index (The EIU, 2020).

Brazil's democratic cultural deficit has a series of repercussions. Due to Brazilians' high mistrust levels, social cooperation is limited (Moisés & Carneiro, 2008). As a result, weak community ties reduce civil society's propensity for common action and further delegates the promotion of solutions for national and local problems to politically institutionalized actors and sphere (Baquero, 2001). Moreover, given low knowledge and interest in politics, Brazilians are not aware of decision-making policy implications on their day-to-day basis. Such environment in which the decision-making process over education, health and economic policies occur without the population's awareness generates fertile ground for the proliferation of corruption, hinders the generation of wealth and increases social vulnerability (Moisés, 2010).

Not by any chance, there is a growing political science and organizational literature pointing to democracy and its values as a socio-political system that can best deal with the changing demands of contemporary civilization in both governmental and businesses contexts (Pateman, 1992; Weber, Unterrainer, & Schmid, 2009). Known as uniting the purposes of individual development and social good, the universal understanding of democracy is at the basis of natural law and political liberalism philosophies (Ward, 2011). Despite criticisms, it is increasingly difficult to deny a democracy's universally relevant political system (Sen, 1999). Withal, growing scientific literature emphasizes the importance of a democratic organizational culture for economic and innovative progress (Adobor, 2020). There are recent studies that show limits to employee knowledge and creativity within non-democratic organizations, hindering business' innovation and competitive expected levels in today's globalized society (Markopoulos & Vanharanta, 2014, 2015). In fact, the most successful 21st century organizations are those that align their structures, policies, procedures and incentives with employees' demands for equality, justice, openness and transparency (Barrett, 2017). These organizations become successful because of the way they make employees feel and the impact this democratic feeling has on team productivity and creativity.

To understand the factors and barriers that undermine a set of behaviors related to an organization's democratic culture and its robust development remains a challenge. To the best of our knowledge, there is no standardized psychometric instrument specifically designed to assess democratic values within an organization and its framework. Mapping these aspects is the first critical step for a proper organizational diagnosis and consequent mapping of potential interventions within the work environment. Assessments of these nature, as recommended by the social sciences and psychology can be done through diverse strategies and techniques. Nevertheless, psychological tests and techniques showcase a holistic picture of the organization and its inclinations in an attempt to implement a democratic agenda within its structure.

The development of a psychometric tool, especially when new, requires proper methodological steps from its conceptualization to its organizational use. These steps include (1) the definition of the general purpose of the measurement tool, its stimuli set, length, and other procedural features, (2) the measurement variables (items), often derived after a literature review of the construct intended to measure; (3) a cultural and contextual adaptation when the language of the items derived from the literature review is different from the language of the target public; in addition to (4) a consultant with specialists to check the adherence and clarity of the items, (5) a pilot and a large-scale testing of the new measure and, finally, (6) an exploration and analysis of the psychometrical and statistical aspects of the tool (Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019; Zickar, 2020).

In summary, when an instrument is conceptualized, a set of studies integrating (1) theoretical assumptions, (2) statistical requirements, and (3) psychometric studies must be carried out as a means to further understand if this tool assesses what it was intended to assess and produces reliable and stable results. In the absence of psychometric studies, the results obtained by this new tool lack scientific interpretation, are limited, and, thus, should not be used (AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014). This is mostly because psychologists assume that responses obtained through a psychological tool may set the ground for latent variables, also known as constructs, and a more precise clinical judgement. Figure 1 summarizes its procedure.

Given there is a lack of standardized measure to assess organizations' democratic culture, this work aims to develop and study the psychometric characteristics of a new metric to evaluate these characteristics. Two studies were conducted: the first carried out a systematic bibliographic review on organizational democratic culture and the national and international literature on psychological measures related to democratic culture. This study was useful to compose a preliminary database of items. The second study was conducted to explore the psychometric evidence of the content of this new measure, as well as to study its internal structure through a multivariate factor analysis.

First Study - Item Development Through Literature Review

Organizational Democratic Culture. Every measurement exercise invariably involves the need to rely on solid theoretical foundation that support the conceptual and methodological choices undertaken in the creation of the instrument. In this sense, it is emphasized that all stages of a conceptual-methodological construction of a given metric is supported, implicitly or explicitly, by a model of conception of the measured reality, that is, a theoretical model that comprises of a clear understanding and non-ambiguous definition of the measured phenomena (Davis, Kingsbury, & Merry, 2012). To this end, several frameworks of philosophical and scientific literature from classical political philosophy to the behavioral contemporary debate were detailed to clarify the foundations and definitions that guided our measure.

The tradition of studies in political culture holds that the functioning and survival of democratic institutions at the systemic level are closely linked to the orientations of values at the individual level (Almond & Verba, 1989; Inglehart & Welzel, 2009). When arguing that different forms of government reflect prevailing citizen virtues, classical thinkers like Aristotle and modern ones, like Tocqueville, understood the fate of a political system to be conditioned by and contingent upon the political attitudes and value orientation of its people. Contemporary scholars defend the existence of a democratic concern that takes more than just institutions and political norms into account: new theories address daily life elements such as customs, collective assumptions, community worldview, and among other social forces that affect people's attitudes and values (Mayer, 2017). Given the complex and profound nature of democratic ideals, formal institutions alone are not able to ensure a democracy's standing; its growth and development demands an expansion of its scope of concerns and influences to encompass civil society and its practices, interactions and values.

Three types of political cultures are derived from the classification of political orientations and objects, namely: I) Parochial political culture - characteristic of societies without strict political institutions and with low levels of political participation and associativism; II) Subordinate political culture - characteristic of societies with low levels of participation and associativism and a passive relationship with the political system; III) Participative political culture - characteristic of societies with a high degree of engagement, knowledge and political participation (Almond & Verba, 1989; Kuschnir & Carneiro, 1999).

On the one hand, contemporary authors argue that a participative political culture, incentivizing citizens to be involved and politically active, while still remaining informed, analytical and rational strengthens democracies (Almond & Verba, 1989). On the other hand, it is also argued that for the sake of a democracy's stability, this model of citizenship must combine traits that may even seem opposed to it, such as temperance, confidence, respect for authority and competence. A democratic culture represents a citizenship model with a predominant participatory political culture that is combined with elements of parochial and subordinate political cultures (Kuschnir & Carneiro, 1999; Lichterman & Cefaï, 2006). The vision of democratic culture incorporates the Aristotelian recommendation of a "mixed government" model: principles of participation and moderation are reconciled in a vibrant political society that does not remain subordinate to the majority.

If cultural variables are of paramount importance for political analysis, psychological structures of the human provide an even more adequate understanding of behavioral phenomena in politics (McGraw, 2006). It has been pointed out that Political Psychology fills an important gap left by Political Science in the analysis of individuals, that is, the analysis of micro-level processes that are behind fundamental traits and democratic behaviors (Borgida, Federico, & Sullivan, 2009). In principle, a psychometric analysis of the individual captures information that is less susceptible to individual biases and social norm influences. In this sense, psychologists draw an important distinction between explicit attitudes that are conscious, and implicit attitudes, located in the subconscious (Truex & Tavana, 2019).

As the dynamics of democratic culture are based on an informal normative structure, at times, far from being explicit, its configuration goes through social attitudes and beliefs that exercise influence through implicit biases (Mayer, 2017). Thus, given that many individual tendencies and inclinations are of an implicit and subconscious nature, it would be unthinkable that only consciously manifested commitment to democratic values and attitudes would sustain a democratic society and its citizenship structure.

In the domain of organizations, however, a democratic culture will invariably manifest itself differently than in the political and social system. In organizations, hierarchy and stakeholders (shareholders, employees, customers, etc.) differ greatly in their rights to participate in the decisions of a company (Harrison & Freeman, 2004). The idea of corporate co-management, for instance, the practice of corporate employees having the right to vote for representatives on the board of directors and the ability to make decisions about the work environment, is widespread in countries like Germany and Austria; but even in these cases, there are important restrictions regarding a minimum company size and reduced scope of decision-making for its practice. It is necessary to emphasize, moreover, that the notion of organizational democracy is not limited to the decentralization of the decision-making process and also encompasses the promotion of democratic principles and values of dialogue, tolerance and trust in the conduct of employee activities (Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, & Blume, 2009).

This study proposes the following operational definition for the concept of democratic culture in organizations: an organizational democratic culture consists of cognitive, community-oriented and evaluate attitudes and dispositions, of a social or psychological nature, in alignment with democratic premises and circumscribed to organizations. This particular constituency requires its own assessment for the organizational environment with a focus on a work environment and work relations.

Methods. Procedure. Because of their comprehensiveness on the subject in addition to their international reach, the following 6 databases were used in the study: Google Scholar, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Periódicos CAPES (Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), Digital Thesis and Dissertation Library (BDTD), Science Gov e Science Research. Moreover, the subsequent keywords and terms chosen were "questionnaire" OR "inventory" AND "democratic culture", with their respective Portuguese version. The timeframe defined for this review included publications from January 2015 to February 2020.

The selection of the documents was based on a screening regarding the title and summary of open-access articles. To be included in the present study, each article had to contain at least a general description of its instruments (questionnaires, interviews, or observational and/or assisted tests) used to evaluate democratic culture and the items used, in addition to a statement of its 'free use' for further research. Duplicated studies or those not available on the internet were excluded from the analyses. The studies selected were analyzed by two independent researchers.

Results. A set of 2,049 works were obtained through the keywords "questionnaire", "inventory", and "democratic culture" (also in Portuguese form) At first, each work was reviewed by the title, abstract and keyword, and was excluded for full review, which clearly did not 1) use an instrument in their search and 2) evaluate democratic culture and it's aspects. Of these works, 104 were duplicate and 1934 were excluded on the basis of the initial review. After the full text of works was read to make an inclusion or exclusion decision, only 11 works remained in the review. The Figure 2 below diagrams this process. In sum, 11 accessible papers were added to the review (Table 1).

After reading these 11 selected articles, a pool of 286 items was formed. Item content varied from the democratic values of tolerance to organizational feelings of belonging: "Most of our social problems would be solved if we could somehow get rid of the immoral, crooked, and feebleminded people" and "Difficult co-workers add to my stress level". Extra items were written by the research team when necessary to further describe the intended purpose and use of this instrument.

Discussion. The aim of this part of the study was to present a systematic literature review on psychometric national and international instruments that measure democratic culture. Some main findings were found: first, the inclusion of only 11 articles suggests the scarcity of previous quantitative research relying on questionnaires or other psychometric instruments. Second, as these articles presented a set of items used to assess a particular aspect of democratic culture, all items forming the preliminary version of pool of items had a conceptual relationship with each other.

An individual's satisfaction with democracy and his or her participation and citizenship levels were subjects very much touched upon in the review. Such repetition of themes demonstrates the importance of these aspects in the context of a democratic culture measure, as well as foretells that the two concepts are suitable for objective assessment within the organizational context. Citizens' satisfaction with democracy is often used as a proxy for democratic regime support in general.

In the Heyne's study, a spatial model of democratic support was developed to evaluate the relationship between citizens' expectations and evaluations of democracy and their levels of satisfaction. Data of 26 countries from the European Social Survey was used and the results suggest that liberal criteria of democratic quality are generally agreed upon amongst citizens, and that perceived lack of realization is the strongest predictor of dissatisfaction (Heyne, 2019).

On the other hand, authoritarian political regimes exist in several patterns and levels, but only one study addressed this subject directly. Thus, while the political culture of an authoritarian regime differs from that of democratic ones, this subject has not yet received much empirical substantiation and partially shows that different types of authoritarian regimes and their classification still remain inchoate, especially within the organizational context.

In sum, the studies obtained by this review assesses democratic cultural features and their manifestation within organizations. Overall, quantitative studies on this topic are still scarce and suggest little consistency in defining and measuring democratic cultures. Such scarcity and lack of consistency make it difficult to describe and/or analyze an organization's democratic culture, its characteristics and determinants. Lack of specialized instruments that capture this construct further prevent actions and strategies enhancing an organization's democratic culture to be initiated.

With the data gathered from this review, the second study describes the statistical approach implemented for the development, evaluation, and refinement of the selected items.

Second Study - Psychometric Properties

Methods. Participants. Two sets of participants formed the second study. Firstly, four specialists assessed the item pool formed by 286 items and evaluated the clarity, pertinence, and quality of the cultural adaptation of each item. These specialists had completed their bachelor in Social Science or any related field. In addition, three of the raters had a Ph.D. either in Political Science, Philosophy or Public Administration, while the fourth has an undergraduate in Business and is an entrepreneur in the field of organizational democracy.

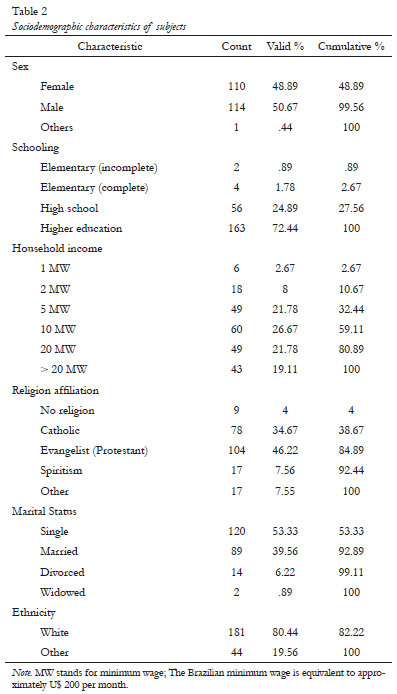

For the factorial study, as will be presented in the procedures section, we developed a specific website and we used a convenient sampling to compose a final sample of 383 volunteers. These participants accessed the data collection dedicated website, but due to missing data, data from a total of 225 individuals were analyzable. Overall, the percentage of men and women was virtually identical (49% vs. 51%) in the study; there was a higher prevalence of people with high education levels (72.44%) and an even higher prevalence of self-reported Caucasians (80.44%). We developed a simple scale for participants which could scroll from a 0 to 6 scale and allocate their political orientation from left to right. The mean was 2.46 (SD = 1.63), suggesting a slightly overall respondent left-wing orientation. Table 2 reports the characterization of the sample.

Procedures. Online data was collected through SurveyMonkey, in which the participants had complete access to the project ethical committee and its registration number in Plataforma Brasil. All eligible participants were instructed to read the consent of research terms and, for those that agreed with the ethical statement, items were displayed anonymously. Before any data collection, this study was submitted and approved by the national and unified registry for research involving human participants with public note 4.125.980.

Data analysis. The first step within the analytical procedure was computing an interpretable score through the content validity coefficient (CVC) algorithm. This was carried out in successive steps, as follows: (1) the average of each specialist's evaluation was computed; (2) this first result was divided by the maximum point of the evaluation scale (5, in this case); (3) an expected error of evaluation was computed, dividing one to the number of judges (in this case, 4) to the power of the number of judges; (4) an individual CVC for each item was generated subtracting the results obtained at step (3) from the results of step (2); and (5) a CVC average was computed considering all of the three aspects assessed. All items with CVC below .70 were suppressed from further analyses.

For the psychometric analysis, the database was initially investigated to ensure its consistency and coding. Categorical variables (e.g., education and sex) were described by their frequencies and proportions, while continuous variables (e.g., age) were described by measures of central tendency, the mean and standard deviation (SD). Missing cases in the instrument's observed variables were imputed using the multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE) method. Sex, demographic region, age, educational level, income, religion, marital status, self-declared ethnicity, and political orientation were included as predictors. The stability of the imputed results relied on the creation of 5 independent databases that were then compared (Erler et al., 2016). All psychometric analyzes were conducted with the imputed data.

The reliability of the data obtained through the psychometric instrument was accessed by Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient and by Guttman's Lambda. The Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) and the Bartlett test were performed as preliminary steps of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), as suggested by the literature (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2014). A polychoric correlation matrix was computed due to its ordinal level, and used as input to explore the dimensionality of the measure. Factorial solutions were obtained by Horn's Parallel Analysis and were fitted to the data and compared. Multidimensional solutions were estimated via the weighted least squares and rotated using oblique methods (geominQ).

The solution was considered adequate if the KMO results were greater than .7 in addition to a significant p-value on the Bartlett test. The final solution chosen considered the most interpretable structure from the theoretical perspective, but also checked if each factor represented at least 3-5 items, with factor loadings higher than .3 or lower than -.3, and no cross-loadings above .30 (Costello & Osborne, 2011). The label of each domain was based on the items with the highest loadings. The internal consistency of each dimension was also explored through Cronbach's alpha.

All analyses were performed with R, with tidyverse, mice, and pysch packages. All codes are freely available at https://osf.io/a6rwf/

Results. In the following paragraphs, we will describe the results related to the Content Validity Coefficient and Factorial Analysis.

Content Validity Coefficient. The adequacy of the items' content was assessed through the content validity coefficient (CVC). Four specialists were asked to evaluate 286 items of the instrument with regard to its clarity, pertinence to the democratic cultural concept, and the overall quality of its contextual and cultural adaptation. The specialists used a rating polytomous scale, in which results could vary from 1 to 5 (1 = not favorable to 5 = favorable). Clarity was defined as the capacity of each item to be concise, readable, and understandable to the target public. Pertinence was defined as the theoretical relationship of the item content to democratic culture. The overall quality of the translation was based on the adaptation to the Brazilian Portuguese language, while maintaining the semantic equivalence of the original item content.

The CVC of each aspect was calculated by the answers of the four specialists. The back-translation scored .93, the language clarity of the items scored .86, and the overall consistency of the content of the items, .84. The average coefficient was .84, providing favorable evidence to the adequacy of the test content. 158 items obtained results below .7 and were thus suppressed from the subsequent analyses; the study resulted in a set of 128 items. A pilot test was conducted with ten professionals, with characteristics similar to those of the study subjects. Their results and suggestions were considered to suppress another set formed of 32 items. The final version of the test contained 96 items and was published on a dedicated webpage online.

Factorial results. Before proceeding with EFA, the KMO (mean value = .76) and Bartlett (X2(4560) = 76380.49 p < .0001test were checked, and their results indicated that factorial procedures could be performed. The dimensionality of the instrument was verified by a parallel analysis in which the polychoric correlation matrix with 1,000 resamplings served as an input.

The scree plot (Figure 4) displays the results of the relationship between the eigenvalues and the number of underlying factors. There are several guidelines in the literature for deciding how many factors should be retained. In this study, the Kaiser criterion (also known as greater than one rule) suggested the retention of 10 factors; conversely, the elbow rule indicates 2 or 3 factors, and the parallel analysis, 5 factors of retention.

Therefore, solutions between 2 and 10 factors were fitted to the data and their results, checked. We combined the current statistical criteria used in multivariate analyses with the proper theoretically interpretation of the retained factor.

The final version of the scale was formed of 58 items oriented in a multidimensional structure, including the 6 correlated factors. Table 3 present all items with their respective psychometric properties. In turn, table 3 reports other results on the psychometric properties of this measure.

The first factor was labelled as "Traditionalist Dogmatism" and composed of items such as "Government is like a father and it should always decide what is good for us" and "God's laws on pornography, abortion, and marriage must be strictly followed without questioning or debate before it is too late". The second factor labeled "Citizen participation" was formed by items such as "To engage in political discussions is very important to be a good citizen" and "We are responsible for the results of politics in everyday life". The third factor labeled "Tolerance and otherness" was composed of items such as "Women should have the same chance of being elected to political office as men" and "I respect people who have opinions contrary to mine". The fourth factor labeled as "Individualism and Rebellion" was composed of items such as "To be a decent person, follow your wishes regardless of the law" and "I feel like rebelling against the authorities even when I know they are right". The fifth factor labelled "Punitive authoritarianism" was formed of items such as "I always insist on having things done my way" and "We must repress troublemakers more harshly". Lastly, the sixth factor was labelled as "Organizational citizenship" and composed of items such as "I often participate in events that are not mandatory but benefit the community of my organization" and "I express my views on work-related matters, even when others disagree".

Conclusions

Although the importance of studying democratic and authoritarian behaviors within work environments remains evident, there is a scarcity of standardized and psychometrically sound instruments that map these attributes in Brazil. In the absence of tests with this profile, the evaluation process of an organizational climate is not formally undertaken and the implementation of employee training program on the matter becomes fragile. Thus, the present study sought to present and discuss steps for the development of a measure of democratic culture in organizations.

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields, which is not exclusive to organizational psychology (Pautasso, 2013). In the literature review carried out in the first study, we gave an overview of current work dealing with democratic and authoritarian cultural measures of organizations. From the 11 results obtained, the debate found in most of the studies described the positive aspects of nurturing a democratic environment and enhancing employee participation within organizations.

The critical reading of these works reveals an almost complete agreement with the importance of adhering to principles of democracy at all levels for the development of a coherent and more humane organizational system and overall healthier work environment for all employees. This result was not surprising. There is evidence suggesting that organizational democracy is associated with increased employee involvement and satisfaction, which tends to increase stakeholder commitment as well as enhance organizational performance (De Jong & Van Witteloostuijn, 2004; Harrison & Freeman, 2004).

However, the success of such endeavor of developing a robust democratic culture within an organization is contingent upon one's ability to map the conditions in which this feature is absent or incipient. Assessing the several forms of political culture in organizations, therefore, has its importance. To a lesser degree, some scholars suggests that a propensity for authoritative behavior might help certain decision-making processes once centralized at the top and once employee-orientation culture is not reinforced or employees are brand new and inexperienced at their jobs (Nicholson, 1998).

After the first study, a pool of 286 items was formed. Despite the fact that these indicators had been developed for the organizational context, their intended construct was different from the democratic culture here defined. Moreover, as some of the items were based on an American and European context, with little or no relationship to the Brazilian society, we needed to write customized items. Four specialists were recruited to evaluate the content of the items; we further computed the CVC for each item to summarize expert ratings on item properties. Specialists encourage this procedure as a means to improve the overall quality of the measure (Anunciação, Da Silva, De Almeida Santos, & Landeira-Fernandez, 2018; Müller & Roodt, 2013).

After the above steps, a first version of the test was complete; as mentioned before, all items were taken from eleven relevant empirical studies and further adapted to the Brazilian context. The empirical data collection was conducted to check the internal structure of this first version and validate the preliminary steps conducted (Baerwalde et al., 2019). The exploratory factor analysis revealed a multidimensional solution and six correlated factors were retained. The number of items varied from 6 to 13 items, but all factors had at least three items loading at .30 or higher (Atkins, 2014; Furr, 2011). The interpretability of this six-factor solution is a key feature of the final solution of the study and was in accordance with the theoretical perspective on political democratic culture (Thompson, 2006).

This study is not free from limitations. Some limitations include low response rate and non-representative sample of data collection. These two features can provide an inaccurate description of the responses, and also jeopardize the reproducibility and external validity of the instrument at hand. Nevertheless, these circumstances and conditions are often present when developing a new psychometric measure. One major limitation in this study relates to the robustness of this new tool. As this psychometric tool was conceived during the study, lack of predictive validity remains. However, current studies are in execution, addressing this limitation.

Improvements in evaluating and assessing an organization's democratic culture on the basis of an accurate organizational diagnosis is important when recommending intervention programs and structural modifications. Moreover, psychological tests can help companies transition and strengthen their organizational democratic cultures by shedding light to leverage indicators needed for them to embark on such democratic mission.

References

Adobor, H. (2020). Open strategy: role of organizational democracy. Journal of Strategy and Management, 13(2),310-331. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-07-2019-0125 [ Links ]

AERA, APA, & NCME. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association. [ Links ]

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1989). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (3rd ed.). Newbury Park, USA: SAGE Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Anunciação, L., Da Silva, S. R., De Almeida Santos, F., & Landeira-Fernandez, J. (2018). Redução da Escala Tendência Empreendedora Geral (TEG-FIT) a partir do Coeficiente de Validade de Conteúdo (CVC) e Teoria da Resposta ao Item (TRI). Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Administrativa, 17(2),192-207. https://doi.org/10.21529/RECADM.2018008 [ Links ]

Atkins, R. (2014). Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in Black Single Mothers. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 22(3),511-524. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.22.3.511 [ Links ]

Baerwalde, T., Gebhard, B., Hoffmann, L., Roick, J., Martin, O., Neurath, A.-L., & Fink, A. (2019). Development and psychometric testing of an instrument for measuring social participation of adolescents: study protocol of a prospective mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 9(2),e028529. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028529 [ Links ]

Baquero, M. (2001). Cultura política participativa e desconsolidação democrática: reflexões sobre o Brasil contemporâneo. São Paulo Em Perspectiva, 15(4),98-104. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-88392001000400011 [ Links ]

Baquero, M. (2003). Construindo uma outra sociedade: o capital social na estruturação de uma cultura política participativa no Brasil. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 21,83-108. [ Links ]

Barrett, R. (2017). A Organização Dirigida por Valores: liberando o potencial humano para a performance e a lucratividade. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil: Alta Books. [ Links ]

Borgida, E., Federico, C., & Sullivan, J. (2009). Introduction: Normative Conceptions of Democratic Citizenship and Evolving Empirical Research. In E. Borgida, C. Federico, & J. Sullivan (Eds.), The Political Psychology of Democratic Citizenship. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Costello, A., & Osborne, J. (2011). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10, np. [ Links ]

Davis, K., Kingsbury, B., & Merry, S. (2012). Introduction: Global Governance by Indicators. In K. Davis, A. Fisher, B. Kingsbury, & S. Merry (Eds.), Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Quantification and Rankings (pp. 3-29). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

De Jong, G., & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2004). Successful corporate democracy: Sustainable cooperation of capital and labor in the Dutch Breman Group. Academy of Management Executive. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2004.14776169 [ Links ]

Erler, N. S., Rizopoulos, D., Rosmalen, J. van, Jaddoe, V. W. V., Franco, O. H., & Lesaffre, E. M. E. H. (2016). Dealing with missing covariates in epidemiologic studies: a comparison between multiple imputation and a full Bayesian approach. Statistics in Medicine, 35(17),2955-2974. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6944 [ Links ]

Furr, R. M. (2011). Scale Construction and Psychometrics for Social and Personality Psychology. 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446287866 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis Seventh Edition. In Pearson New International. [ Links ]

Harrison, J. S., & Freeman, E. R. (2004). Democracy In and Around Organizations: Is organizational Democracy Worth the Effort. Academy of Management Executive, 18(3),6. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2004.14776168 [ Links ]

Heyne, L. (2019). Democratic demand and supply: a spatial model approach to satisfaction with democracy. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 29(3),381-401. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1544904 [ Links ]

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2009). Modernização, Mudança Cultural e Democracia: a sequência do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Brasil: Editora Francis. [ Links ]

Instituto Sivis (2018). Índice de Democracia Local-Curitiba. Curitiba, Brasil. [ Links ]

Instituto Sivis (2019). Índice de Democracia Local-São Paulo. Curitiba, Brasil. [ Links ]

Kuschnir, K., & Carneiro, L. P. (1999). As dimensões subjetivas da política: Cultura Política e Antropologia da Política. Revista Estudos Históricos, 13(24),227-250. [ Links ]

Latinobarómetro. (2018). Informe 2018. Santiago. [ Links ]

Lichterman, P., & Cefaï, D. (2006). The Idea of Political Culture. In R. Goodin & C. Tilly (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis (pp. 392-414). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Markopoulos, E., & Vanharanta, H. (2014). Democratic Culture Paradigm for Organizational Management and Leadership Strategies-The Company Democracy Model. Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, (July), 7673-7684. [ Links ]

Markopoulos, E., & Vanharanta, H. (2015). The Company Democracy Model for the Development of Intellectual Human Capitalism for Shared Value. Procedia Manufacturing, 3,603-610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.277 [ Links ]

Mayer, S. (2017). Resolving the Dilemma of Democratic Informal Politics. Social Theory and Practice, 43(4),691-716. [ Links ]

McGraw, K. (2006). Why and How Psychology Matters. In R. Goodin & C. Tilly (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis (p. 882). New York, USA: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Meneguello, R. (2006). Aspects of democratic performance: Democratic adherence and regime evaluation in Brazil, 2002. International Review of Sociology, 16(3),617-635. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700600931426 [ Links ]

Moisés, J. A. (2010). Politica Corruption and Democracy in Contemporary Brazil. Revista Latinoamericana de Opinión Pública, 1(0),1-27. [ Links ]

Moisés, J. Á. (2008). Cultura política, instituições e democracia: lições da experiência brasileira. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 23(66),11-41. [ Links ]

Moisés, J. Á., & Carneiro, G. P. (2008). Democracia, desconfiança política e insatisfação com o regime: o caso do Brasil. Opinião Pública, 14(1),1-42. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-62762008000100001 [ Links ]

Müller, K. P., & Roodt, G. (2013). Content validation: The forgotten step-child or a crucial step in assessment centre validation? SA Journal of Industrial Psychology. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1153 [ Links ]

Muñiz, J., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2019). Ten steps for test development. Psicothema, 31(1),7-16. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.291 [ Links ]

Nicholson, N. (1998). How hardwired is human behavior? Harvard Business Review. [ Links ]

Pateman, C. (1992). Participação e Teoria Democrática. São Paulo, Brasil: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9(7),e1003149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149 [ Links ]

Podsakoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & Blume, B. D. (2009). Individual-and Organizational-Level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1),122-141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013079 [ Links ]

Sen, A. (1999). Democracy as a universal value. Journal of Democracy, 10(3),3-17. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10193-011-0020-1 [ Links ]

The EIU. (2020). Democracy Index 2020 In sickness and in health ? London, UK. [ Links ]

Thompson, B. (2006). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. In Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. https://doi.org/10.1037/10694-000 [ Links ]

Truex, R., & Tavana, D. L. (2019). Implicit attitudes toward an authoritarian regime. Journal of Politics, 81(3),1014-1027. https://doi.org/10.1086/703209 [ Links ]

Ward, L. (2011). Benedict Spinoza on the Naturalness of Democracy. Canadian Political Science Review, 5(1),55-73. [ Links ]

Weber, W. G., Unterrainer, C., & Schmid, B. E. (2009). The influence of organizational democracy on employees ' socio-moral climate and prosocial behavioral orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30,1127-1149. https://doi.org/10.1002/job [ Links ]

Zickar, M. J. (2020). Measurement Development and Evaluation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1),213-232. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044957 [ Links ]

Information about the authors:

Information about the authors:

Lucas Barrozo de Andrade

E-mail: lucas.psic.rj@gmail.com

Natasha Alvarez

E-mail: natasha.alvarez97@gmail.com

Diego Moraes

E-mail: diego@sivis.org.br

Wayson Maturana

E-mail: wmaturanapsi@gmail.com

Anna Carolina Portugal

E-mail: portugal.aca@gmail.com

Jesus Landeira-Fernandez

E-mail: landeira@puc-rio.br

Luis Anunciação

Departamento de Psicologia

Rua Marques de São Vicente, 225/L201

22451-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

E-mail: luisfca@puc-rio.br

Submission: 09/12/2020

First Editorial Decision: 08/03/2021

Final Version: 19/03/2021

Accepted in: 24/03/2021