Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

Print version ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. vol.40 no.1 Porto Alegre Apr. 2006

Honesty in multicultural counseling: a pilot study of the counseling relationship

Honestidad en la consejería multicultural: un estudio piloto de la relación de consejería

Edil Torres Rivera1,I; Loan T. PhanII ; Cleborne D. MadduxIII; Janice Roberts WilburIV; Patricia ArredondoV

I University of Florida, Gainesville, USA

II University of New Hampshire, Durham, USA

III University of Nevada, Reno, USA

IV University of Connecticut, Storrs, USA

V Arizona State University, Tempe, USA

RESUMEN

Este estudio investigo las destrezas de consejería y las relaciones humanas (la orientación relacional) en un grupo de 17 consejeros en preparación durante un curso de 14 semanas. Los resultados indicaron que las destrezas de esto consejeros en preparación cambian cuando ellos llegan a tener más conocimiento de sí mismos durante la supervisión de grupo multicultural.

Palabras-clave: Honestidad, Consejero educador, Adiestramiento.

ABSTRACT

This study assessed counseling skills and human relationships (relational orientation) in a group of 17 counselorsin- training during a 14-week counseling course. The results indicated that counselor trainees’ counseling skills change as they become more aware of themselves during multicultural group supervision.

Keywords: Honesty, Counselor educator, Training.

The official monthly newspaper of the American Counseling Association (Marino, 1996) presented the results of an informal survey indicating that one of the reasons why non-Caucasian people did not seek counseling when in need was because they believed that counselors were not “real.” Non-Caucasian people stated that counselors appeared too perfect, distant, and unable to understand non-Caucasian issues. Similar results have been found by other social scientists linked to the counseling profession (Jenkins, 1995; Mearns, 1997; Pedersen, 1997; Sue, 1997; Sue, Ivey, & Perdersen, 1996).

The importance of the counseling relationship is emphasized in every introductory counseling textbook (Brown & Srebalus, 1996; Cormier & Cormier, 1998; Gladding, 2004; Srebalus & Brown, 2001; Vacc & Loesch, 1993). However, in many instances, the focus of counselor training is on professional relationships (professional orientation) with little attention given to personal relationships or self-identity. There is often little information about how counselors-in-training can gain a better understanding of themselves and their clients, especially if those clients come from ethnic minority groups. This may be due partly to the fact that many training models in counseling concentrate on skills development from behavioral perspectives and rely primarily on less realistic methods such as role playing (Koch & Dollarhide, 2000; Larson et al., 1999; Pinterits & Atkinson, 1998; Rabinowitz, 1997; Urbani et al., 2002).

There is evidence that most of the information about self-understanding, self-awareness, and honesty that counselors-in-training receive comes from ethics and multicultural courses2 . In fact, there is strong evidence suggesting that the only course that requires students to examine their self-identity and provide students with models of identity development is the multicultural course (Dinsmore & England, 1996; Dinsmore & Hess, 1999; Pope-Davis & Coleman, 1997; Torres-Rivera, Phan, & Garrett, 2000). An index of the need for attention to such topics was seen in a study that reviewed over 100 email messages on the counselor educators network (CESNET) in the United States. These messages indicated the presence of concern about students cheating on examinations, the fact that students have little tolerance for discomfort, and a number of other self-awareness and honesty issues (Hazler, 2000).

Two different listserves (LATNET-L@LISTS.UFL.EDU; CESNET-L@LISTSERV.KENT.EDU) of counselor educators in the United States were used to ask about honesty. In CESNET, the posted question asked respondents how honest they believe counselors to be. Responses differed widely, with some people stating that “honest is honest and that is it,” to others stating that honesty is situational and at times one must be careful about when, what, and to whom one is honest (Torres-Rivera, 2001a, 2001b). The second group was asked in which course honesty is most frequently addressed. Again, responses were mixed. A few respondents stated that honesty is addressed in every course. However, the majority suggested that honesty is addressed mainly in multicultural courses.

This may be a problem, since many of the programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) offer only one course in multicultural counseling (CACREP, 2001; Dinsmore & England, 1996; Dinsmore & Hess, 1999; Torres-Rivera, Phan, & Garret, 2000). In such programs, there is a limited time that counselors-in-training can experience and explore their own self-identity, self-understanding, and existence as healers in a quasi-therapeutic environment (Torres-Rivera, 2001c; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). This is unfortunate because a number of studies have shown that the process in which people learn about differing worldviews and develop an appreciation for such worldviews requires at least two or three courses over a period of no less than one year (Garcia, Wright, & Corey, 1991; Jenkins, 1995; Rest & Narváez, 1994). The importance of such experiences is obvious in light of the fact that counselors are increasingly working with people with different worldviews.

The worldview variable has been extensively researched from at least two different perspectives: the value-orientation model developed by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) and the locus of control model developed by Rotter (1966). Both perspectives support the contention that in order to be an effective multicultural counselor, the counselor must understand the client’s worldview (Ibrahim, 1985, 1991; Ivey, Ivey, & Simek-Downing, 1997; Sue, Ivey, & Pedersen, 1996; Sue & Sue, 2003). In addition, counselors must have a clear understanding of their own worldviews before they can develop an appreciation for worldviews of ethnically diverse clients (Helms & Cook, 1999; Pedersen, Draguns, Lonner, & Trimble, 1996; Sciarra, 1999; Sue, Ivey, & Pedersen, 1996; Sue & Sue, 2003).

Research indicates that some multicultural training programs have done an adequate job in helping counselors-intraining develop awareness of their own worldviews as well as the worldviews of those from other cultures (Dinsmore & England, 1996; Dinsmore & Hess, 1999; Torres-Rivera, Phan, & Garret, 2000). However, counselor educators may not understand the importance of the relational orientation to multicultural counseling competencies, particularly at http:// unr.edu/homepage/smaby/syl795.html for examples of syllabi.when looking beyond professional roles (Jenkins, 1995; Mearns, 1997; Wilbur, 1992). Furthermore, while counselorsin- training are exposed to social identity in the form of professional orientation by means of courses in ethics and introduction to the counseling profession, self-identity (personal orientation) is addressed primarily in multicultural courses. Unfortunately, all too often these courses are organized almost exclusively around the professional orientation variable (Cormier & Cormier, 1998; Gladding, 2004; Salazar, 1999; Torres-Rivera, Phan, & Garrett, 2000; Wilbur & Roberts- Wilbur, 1986). This issue becomes even more critical when we consider that since Carl Rogers (1942, 1951, 1957, 1970), the importance of being in a “real relationship” or “being real” has constantly been named as one of the most important elements for the counseling process to be effective (Gladding, 2004; Harman, 1995; Jenkins, 1995; Mearns, 1997; Schaef, 1992, 1999; Sue & Sue, 2003; Wilbur, 1992).

Honesty has long been equated with “being real,” “real relationships,” “authenticity, transparency, genuineness, and congruence” (Ivey, Ivey, & Simek-Downing, 1997; Moustakas, 1966; Rogers, 1970; Schaef, 1992, 1999; Wilbur, 1992; Wilbur & Roberts-Wilbur, 1986). That is, counselors need to include these concepts in the development of their unique personal style of counseling in order to be effective (Ivey, Ivey, & Simek- Downing, 1997; Jenkins, 1995; Mearns, 1997; Rogers, 1970; Wilbur, 1992).

For the purpose of this study, honesty is defined as truthfulness (Miner & Capps, 1996; Murphy, 2000), because this definition is consistent with recent studies that also equate truthfulness with the elements listed above (being real, real relationships, authenticity, transparency, genuine, and congruency with oneself) (Ashton, Lee, & Son, 2000; Elm, 1998; Nicol, 2000; Sackett & Wanek, 1996).

While many of the multicultural counseling textbooks discuss the need for the integration of awareness and skills with all aspects of counseling, including the multicultural competencies, these references seldom include honesty as one of the main ingredients in preparing competent multicultural counselors (Arredondo et al., 1996; Helms & Cook, 1999; Pedersen, Draguns, Lonner, & Trimble, 1996; Sciarra, 1999; Sue & Sue, 2003). Thus, integrating a multicultural counseling style that is effective and that corresponds with the counselor’s style of working with ethnic minority populations may not be accomplished. To rectify this problem, counselors should to learn to integrate personal awareness and skills that emphasize honesty during their course work rather than after their graduate training is completed.

Research in multicultural counseling supports the notion that skills and/or knowledge alone do not lead to effective counseling practices (Green, 1998; Martinez, 1994; Sue & Sue, 2003). What appears to be significantly different in effective helping relationships is the use of models that take cultural differences into account and include honesty as one of the important personal characteristics of the counselor (Martinez, 1994).

Following these premises, the purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of students’ participation in a multicultural counseling course on their personal development (establishing an honest relationship with themselves) and multicultural counseling competencies. This course and the training were based on Wilbur, Roberts-Wilbur, Morris, Betz, and Hart’s (1991) structured group supervision model. The model was modified to accommodate the integration of personal awareness and skills during the fourteen weeks of training. For this study the following assumptions were made:

1) Honesty is synonymous with authenticity, genuineness, congruency, and realness, which is also truthfulness. Therefore, to expand on the definition of honesty and for the purpose of this study, honesty was defined as the ability of counselors to demonstrate skills such as: a) perception - the ability of the counselor to be aware of her or his sensory perceptions; b) feedback – giving and receiving feedback that is in harmony with the counselor’s sensory perceptions; c) directness – the ability to display candor and to be open, moving beyond the “everything is all right” pretense; d) recovery skills – which are sequential to directness, as directness may create conflict or discomfort to the client, and the counselor may need to respond with care, acceptance, and empathy; e) confrontation – the ability to recognize and point out incongruity; f) selfdisclosure – the ability to be real and transparent; and g) interpretation – a clear understanding of the client situation (for a detailed explanation of these skills and the connection with honesty, see Wilbur & Roberts-Wilbur, 1986). While these definitions may not seem universal, they are supported by the theoretical premises presented by Dollard and Miller (1950), Moustakas (1966), Wilbur (1992), Wilbur and Roberts-Wilbur (1986), and Torres-Rivera (2002). The authors assume that counseling skills entail paying attention to oneself and others in the entire verbal and nonverbal matrix of communication. Thus, it is possible to measure honesty as counseling skills using the Counseling Skill Personal Development Rating Form (CSPD-RF) (Torres-Rivera, 2002).

2) If relationships are cultivated in an environment such as group settings where group dynamics may change, then the relationships among group members may also change. Therefore, it is possible to measure the dynamics as well as the relationship development by using the Group Dynamics Inventory (GDI) (Phan, 2001; Phan & Torres-Rivera, 2000; Phan, Torres Rivera, Volker, & Garrett, 2004).

3) A necessary component of honesty and real relationships includes awareness of one’s sensory perceptions and life experiences (Moustakas, 1966).

4) Counselors as well as other mental health professionals are taught to be polite, kind, pleasing, and socially/ professionally appropriate rather than to be honest and consistent in their perceptions of themselves and their clients (McLellan, 1999; Torres-Rivera, 2001a; Wilbur, 1992; Wilbur & Roberts-Wilbur, 1986).

5) As counselors-in-training become more honest with themselves, it becomes easier and more natural for them to be honest with others to whom they feel close. Group dynamics is the vehicle in which this environment is created and nurtured. Therefore, as a result of these group dynamics, counselors-in-training will increase their ability to understand the counseling relationship and their clients’ problems (Phan, 2001).

The Null Hypotheses were: H01: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no change in their personal development as measured by the GDI (Phan, Torres Rivera, Volker, & Garrett, 2004) at six different occasions. H02: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no change in their counseling skills and honesty as measured by the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) at six different occasions. H03: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no relationship between personal development of counselors-in-training and their counseling skills. H04: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no relationship between personal development of counselors-intraining and honesty.

Method

Participants

The participants (counselors-in-training/students) were 17 master’s degree students who completed at least one semester of counseling courses including a practicum and a theory course. There were 15 females and two males with a mean age of 31 years (range = 23-54). Two of the 17 students described themselves as members of ethnic minority groups (Asian American and Latina). All of the participants were students at a large institution in the western United States. The university was a Land Grant Institution and the program was accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). The students were enrolled in a 60- credit master’s degree program.

Instruments

The Counselor Skills and Personal Development Rating Form. The Counselor Skills and Personal Development Rating Form (CSPD-RF; Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) consists of 20 items with each item containing a statement about the counselor trainee’s counseling skills that are rated after watching a counseling session. The CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) measures counseling skills as well as personal development. Each item is followed by six, Likert-type scale responses ranging from 1 (unacceptable) to 6 (outstanding). The higher number indicates a greater presence of counseling skills and personal development while the lower number indicates little or the absence of a particular counseling skill. The CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) was developed to investigate counseling skills such as emotional sensitivity, basic listening skills, multicultural skills, and influencing skills. The listening and basic listening skills are listed as skill development and the multicultural and emotional sensitivity skills are listed under personal development in accordance with a recent study of this instrument (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) (see assumption 1). As stated earlier, honesty is defined as the ability of counselors to demonstrate skills such as: a) perception, b) feedback, c) directness, d) recovery skills, e) confrontation, f) self-disclosure, and, g) interpretation. Therefore, the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera, et al., 2002) can measure these skills under emotional sensitivity, basic listening skills, multicultural skills, and influencing skills.

In this study, the internal consistency for all 20 items of the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951). A coefficient of .83 was found. This coefficient is consistent with previous studies using the CSPD-RF in which Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .95 (Torres-Rivera, Phan, Maddux, Wilbur, & Garrett, 2001) and .91 (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002). Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated for the subscales and were as follows: emotional sensitivity - .89; basic counseling skills - .83; multicultural counseling skills - .88; and influencing skills - .92. Again, this is consistent with previous studies (see Torres-Rivera et al., 2001 and Torres-Rivera et al., 2002). In addition, this instrument has been used in a content validity study of another instrument, The Skilled Group Counseling Scale (Smaby, Maddux, Torres, & Zimmick, 1997), which has been used to evaluate and measure skills development of counselors-in-training during group supervision (Downing, 1999; Smaby, Maddux, Torres-Rivera, & Zimmick, 1999; Zimmick, Smaby, & Maddux, 2000). For more information about the psychometric properties of the CSPD-RF see Torres- Rivera et al. (2002).

Group Dynamics Inventory. The Group Dynamics Inventory (GDI) (Phan & Torres Rivera, 2000) is a 20- item, self-report survey that makes use of a four-point, Likert-type scale. The items are various statements about the group member’s feelings, behaviors, and/or thinking during and after the group session.

In the initial study in which the GDI was developed (Phan, 2001; Phan et al., 2004), the literature addressing group work and group dynamics was comprehensively reviewed. A particular focus was placed on the therapeutic existential factors that assist groups in attaining a therapeutic level and on experiential data gathered over the last two years while performing structured group supervision (Corey, 1995; Corey & Corey, 1997; Forsyth, 1999; Frank-Saracini, Wilbur, Torres-Rivera, & Roberts- Wilbur, 1998; Gladding, 2004; Posthuma, 1996; Yalom, 1995). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951) was calculated to determine internal consistency of the GDI total scores for three different groups. These ranged from .92 to .95.

An exploratory factor analysis as recommended by Gable and Wolf (1993) was recently conducted to address construct validity (Phan, 2001). Three factors (altruism, cohesiveness, and universality) were found producing factor loadings ranging from .50 to .83. A varimax rotation established evidence for construct validity of the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) by revealing a clearer factor structure that showed three factors that accounted for 69% of the variance.

The predictive validity of the GDI (Phan, 2001; Phan et al., 2004) was investigated during the development of the GDI by using a nonparametric validation technique involving the Mann-Whitney U test (Siegel & Castellan Jr., 1988). Two group counseling experts divided the students into two groups: a) those who showed a high level of group dynamics (altruism, cohesiveness, and universality), and, b) those who did not show a high level of group dynamics. The survey was then administered to both groups to see if the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) results matched the observations made by the two group counseling experts (Phan, 2001). Their observations matched 90% of the time or better. For more information about the GDI psychometric properties, see Phan (2001).

Design and Procedure

This study was a quasi-experimental design study in which the investigators were interested in discovering if change over time occurred in students’ counseling skills and group dynamics while attending a multicultural counseling course in which honesty and personal development were encouraged. Also, the investigators for this study were interested to see if there was a relationship between the dependent variables. Consequently, this study was an exploratory study derivative from curiosity (Amundson, Stewart, & Valentine, 1993; Green, 1998; McGoldrick, 1998; Winddance Twine & Warren, 2000) and not from the rigid scientific approach. Nonetheless, the assumptions for simple repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were met (Hinkle, Wiersma, & Jurs, 1988; Huck, 2000). Therefore, the two dependent variables of personal awareness and counseling skills were investigated. Personal awareness was assessed by using the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) and counseling skills were assessed using the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002). It is important to emphasize that the honesty construct in this study is based on the definition given earlier which equated honesty with truthfulness, “being real,” congruency, etc. (elements included in the four factors of the CSPD-RF).

The CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) and the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) were distributed on six different occasions (during the 14-week duration of the course) by the investigators to 17 counselors-in-training enrolled in a multicultural counseling course. The selection of the participants was based on a purposive sample of convenience (Huck, 2000; Sprinthall, 1997) that was composed of 12% of the total population of the counseling student body (147 students at the time of the study) from which the sample was taken. The multicultural counseling course was structured in accordance with the five-phase schema supervision model developed by Wilbur et al. (1991).

During the first two weeks of class students were asked to relate to an idea, theory, or belief about how and why people, including themselves, change. They were presented with values clarification exercises in which they were to question themselves about the nature of behavioral change (for example, does knowledge and/or experience lead to behavioral change). During this first phase, counselors-in-training were also asked about their beliefs concerning human nature (good, evil, a combination, or neutral). A review and analysis of the Microtraining (2000) multicultural counseling tapes using the CSPD-RF (Torres- Rivera et al., 2002) was also part of this first phase. This first phase was based on theories of moral development which indicated that changes in behavior grounded in moral and cognitive development will not appear until after the individual has had time to internalize the information given (Rest & Narváez, 1994). Therefore, a pretest or baseline test was not administered until four weeks into the course.

The second phase of the model called for the instructor to demonstrate how to counsel a client from an ethnic minority group. Counselors-in-training were asked to observe and to formulate questions/clarification about the group dynamics and process. The demonstration was live and did not include role playing or fictitious problems.

In the third phase of this model, counselors-in-training were asked to counsel an ethnic minority client. Each counselor-in-training was required to demonstrate at least one 60-minute counseling session during the semester, while the rest of the class observed the counseling session. After the 60-minute counseling session, the class (including the performing counselor-in-training) took a 10- minute break in which they were asked to reflect on the counselor-in-training’s performance. After the class reconvened, the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) and GDI (Phan et al., 2004) were given to all counselors-intraining, including the counselor-in-training doing the counseling session, to evaluate the performance of the counselor-in-training and the group dynamics of the class.

The fourth phase consisted of the person conducting that particular demonstration on that day telling the class and the instructor what they thought they did well and what they would do differently. In turn, the rest of observing counselors-in-training offered feedback to the performing counselor-in-training. The performing counselor-intraining also had the opportunity to respond to the feedback. Again, every counselor-in-training (n=17) had the opportunity to demonstrate and to provide feedback in the course of the semester (one at a time per class).

The final phase of the model was a group discussion period about all the events of the day. (See Wilbur et al., 1991 for more details about the Structured Group Supervision model).

Data Collection Procedure

During the fourth week of class, the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) and CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) were administered for the first time. The CSPD-RF (Torres- Rivera et al., 2002) and the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) were collected before beginning the fourth phase of the personal development model. The CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) and the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) were administered every other week after the fourth week for a total of six different testing periods.

Data Analysis. The data collected by the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) and GDI (Phan, 2001; Phan et al., 2004) instruments were analyzed by using two separate repeated measures ANOVAs. Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficients were calculated to check for relationships between group dynamics and counseling skills (Hinkle, Wiersma, & Jurs, 1988). The analyses were conducted using the JMP statistical program (SAS, 2000).

Results

For H01: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no change in their personal development as measured by the GDI

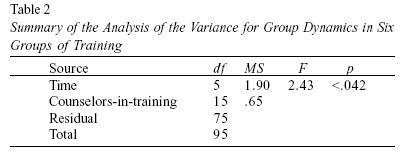

(Phan et al., 2004) at six different occasions. The scores of the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) test were subjected to a repeated measures ANOVA, which yielded a significant group effect, F(5, 15) = 2.43, p<.05, h ²81 (see Table 2). A comparison of the means using a Tukey’s HSD (honestly significant difference) post hoc test indicated that the first set of the GDI mean scores were significantly different from the fourth set of mean scores at the .05 significance level. Power analysis was conducted using JMP statistical discovery software (SAS, 2000) to determine whether we have an adequate sample size to detect differences. The power analysis indicated that the sample size for the analysis were sufficient to detect a different at a power of .62 at the .05 level of significance. Therefore, the null was rejected.

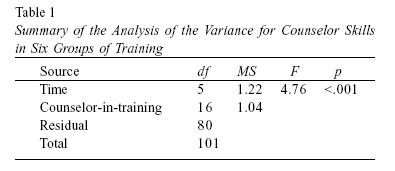

For H02: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no change in their counseling skills and honesty as measured by the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) at six different occasions The scores of the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) test were subjected to a repeated measures ANOVA, which yielded a significant group effect, F(5, 16) = 4.76, p<.001, h²=. 88 (see Table 1). A Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) post hoc test indicated that the first set of the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) mean scores at p <.05 level of significance were significantly different from the second and fifth set of mean scores. Power analysis was conducted using JMP statistical discovery software (SAS, 2000) to determine whether we have an adequate sample size to detect differences. The power analysis indicated that the sample size for the analysis were sufficient to detect a different at a power of .74 at the .05 level of significance. Therefore, the null was rejected.

For H03: In the population from which the sample is drawn (counselors-in-training), there will be no relationship between personal development of counselorsin- training and their counseling skills and H04: In the population from which the sample is drawn, there will be no relationship between personal development of counselors-in-training and honesty.

When the two variables were compared, the findings indicated that as the group dynamics changed in the class, the ability of the counselors-in-training to recognize their limitations as counselors also changed. Also, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to search for relationships between group dynamics and counseling skills (Hinkle, Wiersma, & Jurs, 1988; SAS, 2000). The analysis found that all but the first scores (r²=.53) of the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002) and the GDI (Phan et al., 2004) were highly correlated (ranging from r²=.86 to r²=.59). It was not clear why the first set of scores were not correlated. Therefore, the nulls were rejected.

Given the definition for honesty used in this study (the ability of counselors to demonstrate skills such as: a) perception, b) feedback, c) directness, d) recovery skills, e) confrontation, f) self-disclosure, and, g) interpretation) and the findings of this study, the researchers concluded that honesty helped the counselors-in-training improve their counseling skills as demonstrated by the CSPD-RF (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002). Similarly, the group dynamics seemed to changed and facilitated a feeling of safety among counselors-in-training, resulting in an honest exchange of ideas and feedback.

Discussion

The findings indicated that personal development as shown by group dynamics have an impact on skills development of counselors-in-training. Furthermore, this research may indicate that knowledge without experience is inadequate. It may also indicate that skills without an understanding of why interventions are being made are insufficient (Harman, 1995; Schaef, 1992, 1999; Torres- Rivera et al., 2001; Yalom, 1995).

It is also important to point out that personal development must be an important component in teaching counselors about multicultural counseling, particularly when personal development is link to honesty as this study demonstrate. This is particularly true when working with counselors-in-training, because their job is to assist people to have a better quality of life. Skills-based models are easy to implement because they are mechanical and uninvolved, while personal development models demand involvement and spontaneity. It is the experience of the authors that students seem to respond better to a more realistic approach even when it could be emotionally draining.

The critical issue may be that counselors-in-training are taught to sacrifice honesty for politeness, kindness, and avoidance of conflict, a finding supported in the mental health field (McLellan, 1999; Schaef, 1999; Torres- Rivera, 2001c; Wilbur & Roberts-Wilbur, 1986). In other words, in the search for something that is easier to teach and to measure (such as techniques and skills), the profession may have abandoned some important counseling components: honesty, authenticity, congruency, and genuineness. More importantly, ethnic minority clients may often see through the politically correct evasions of multicultural counselors who are too skills-oriented. Therefore, if counselors-in-training are to be effective with a population that is not necessarily concerned about being politically correct, they must redefine and add to their training the component of “honesty” as a base ingredient to their helping style as healers.

Limitations. The limitations for the study are related to the small sample size (n=17). Another limitation of this study deals with reliability and validity of the instruments used to measure group dynamics and counseling skills. Since the results were self-reported, social desirability may have influenced counselor trainees’ truthfulness.

Referencias

Amundson, J., Stewart, K., & Valentine, L. (1993). Temptations of power and certainty. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 19, 111-123. [ Links ]

Arredondo, P., Toporek, R., Brown, S., Jones, J., Locke, D. C., Sanchez, J., & Stadler, H. (1996). Operationalization of the multicultural counseling competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development. Alexandria: American Counseling Association. [ Links ]

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Son, C. (2000). Honesty as the sixth factor of personality: Correlations with Machiavellianism, primary psychopath, and social adroitness. European Journal of Personality, 14, 359-369. [ Links ]

Brown, D., & Srebalus, D. S. (1996). Introduction to the counseling profession (2nd ed.). Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Corey, G. (1995). Theory and practice of group counseling (4th ed.). Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Corey, M. S., & Corey, G. (1997). Groups: Process and practice (5th ed.). Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Cormier, W. H., & Cormier, S. L. (1998). Interview strategies for helpers: Fundamental skills and cognitive behavioral intervention (4th ed.). Monterey: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2001). Directory of Accredited Programs [On-line]. Available: http://www.counseling.org/cacrep/directory.htm. Retrieved: October, 2001. [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297. [ Links ]

Dinsmore, J. A., & England, J. T. (1996). A study of multicultural counseling training at CACREP-accredited counselor education programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 58-76. [ Links ]

Dinsmore, J. A., & Hess, R. S. (1999, October). Multicultural counseling competencies: What’s really being taught in counselor education programs? Paper presented at the National Conference of the Association of Counselor Education and Supervision, New Orleans, USA.

Dollard, J., & Miller, N. E. (1950). Personality and psychotherapy: An analysis in terms of learning, thinking, and culture. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Downing, T.K. (1999). A study of the transfer of group counseling skills from training to practice. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, USA. [ Links ]

Elm, D. R. (1998). The three faces of honesty: A confirmatory factor analysis. In J. Post (Ed.), Research corporate social performance and policy (pp. 107-123). Stanford: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Forsyth, D. R. (1999). Group dynamics (3 rd ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Frank-Saracini, J., Wilbur, M., Torres-Rivera, E., & Roberts-Wilbur, J. (1998). GCT: Structure and chaos of group supervision. Paper presented at the annual convention of the North Atlantic Association for Counselor Education and Supervision, Wells, USA. [ Links ]

Gable, R. K., & Wolf, M. B. (1993). Instrument development in the affective domain: Measuring attitudes and values in corporate and school setting (2nd ed.). Norwell: Kluwer. [ Links ]

Garcia, M. H., Wright, J. W., & Corey, G. (1991). A multicultural perspective in an undergraduate human services program. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 86-90. [ Links ]

Gladding, S. T. (2004). Counseling a comprehensive profession (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Green, R. (1998). Training programs: Guidelines for multicultural transformation. In M. McGoldrick (Ed.), Re-visioning family therapy: Race, culture, and gender in clinical practice (pp. 111-117). New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Harman, R. L. (1995). Gestalt therapy techniques: Working with groups, couples, and sexually dysfunctional men. Northvale: Jason Aronson. [ Links ]

Hazler, R. (2000). Making or breaking a counselor educator’s spirit? [Online]. Available: http://CESNET-L@LISTSERV.KENT.EDU. Retrieved: June 11, 2000.

Helms, J. E., & Cook, D. A. (1999). Using race and culture in counseling and psychotherapy: Theory and process. Needham: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Hinkle, D. E., Wiersma, W., & Jurs, S. G. (1988). Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Huck, S. W. (2000). Reading statistics and research (3rd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, F. A. (1985). Effective cross-cultural counseling and psychotherapy: A framework. The Counseling Psychologist, 13, 625- 683. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, F. A. (1991). Contribution of cultural worldview to generic counseling and development. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 13-19. [ Links ]

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Simek-Downing, L. (1997). Counseling and psychotherapy: A multicultural perspective (4th ed.). Needham: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P. (1995). Two models of counselor training: Becoming a person or learning to be a skilled helper? Counseling, 6(3), 203-206. [ Links ]

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L.(1961). Variations in value orientations. Evanston: Row, Peterson. [ Links ]

Koch, G., & Dollarhide, C. T. (2000). Using a popular film in counselor education: Good will hunting as a teaching tool. Counselor Education and Supervision, 39, 203-210. [ Links ]

Larson, L. M., Clark, M. P., Wesley, L. H., Koraleski, S. F., Daniels, J. A., & Smith, P. L. (1999). Videos versus role plays to increase counseling self-efficacy in prepractica trainees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38, 237-248. [ Links ]

Marino, T. W. (1996). The challenging task of making counseling services relevant to more populations: Reaching out to communities and increasing the cultural sensitivity of counselors-in-training seen as crucial. Counseling Today, August, 1-6. [ Links ]

Martinez, C. (1994). Psychiatric treatment of Mexican-Americans: A review. In C. Telles & M. Karno (Eds.), Latino mental health: Current research and policy perspectives (pp. 227-340). Los Angeles: National Institute of Mental Health, Neuropsychiatry Institute. (N.I.M.H. Publication No. 94MF04837-24D). [ Links ]

McGoldrick, M. (Ed.). (1998). Re-visioning family therapy: Race, culture and gender in clinical practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

McLellan, B. (1999). The prostitution of psychotherapy: A feminist critique. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 27(3), 325-337. [ Links ]

Mearns, D. (1997). Achieving the personal development dimension in professional counsellor training. Counseling, 8(2), 113-120. [ Links ]

Microtraining Associates (2000). Culturally-competence counseling & therapy. North Amherst: Author. [ Links ]

Miner, J. B., & Capps, M. H. (1996). How honesty testing works. Westport: Quorum Books. [ Links ]

Moustakas, C. E. (1966). Honesty, idiocy, and manipulation. Unpublished manuscript, Merrill-Palmer Institute, Detroit, USA. [ Links ]

Murphy, K. R. (2000). What constructs underline measures of honesty or integrity? In R. D. Goffin & E. Helms (Eds.), Problems and solutions in human assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at seventy (pp.265-283). Boston: Kluwer Academic. [ Links ]

Nicol, A. (2000). A measure of workplace honesty. Dissertation Abstracts International, 60(9), 4946 B. (University Microfilms No. AAINQ42548). [ Links ]

Pedersen, P. B. (1997). Culture-centered counseling interventions: Striving for accuracy. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Pedersen, P. B., Draguns, J. G., Lonner, W. J., & Trimble, J. E. (1996). Counseling across cultures (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Phan, L. T. (2001). Structured group supervision from a multicultural perspective. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, USA. [ Links ]

Phan, L. T., & Torres-Rivera, E. (2000). Group dynamics inventory. Unpublished instrument, University of Nevada, Reno, USA. [ Links ]

Phan, L. T., Torres-Rivera, E., Volker, M. A., & Garrett, M. T. (2004). Measuring group dynamics: An exploratory trial. Canadian Journal of Counseling. 38(4), 234-245. [ Links ]

Pinterits, J. E., & Atkinson, D. R. (1998). The diversity video forum: An adjunct to diversity sensitivity in the classroom. Counselor Education and Supervision, 37, 203-212. [ Links ]

Pope-Davis, D. B., & Coleman, H. L. K. (1997). Multicultural counseling competencies: Assessment, education and training, and supervision. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Posthuma, B. W. (1996). Small groups in counseling and therapy: Process and leadership. Needham: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Rabinowitz, F. E. (1997). Teaching counseling through a semester-long role play. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 216-223. [ Links ]

Rest, J. R., & Narváez, D. (Eds.). (1994). Moral development in professions: Psychology and applied ethics. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. R. (1942). Counseling and psychotherapy. Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client centered therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95-103. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. R. (1970). Carl Rogers in encounter groups. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1-28. [ Links ]

Sackett, P. R., & Wanek, J. E. (1996). New developments in the use of measures of honesty, integrity, conscientiousness, dependability, trustworthiness, and reliability for personnel selection. Personnel Psychology, 49, 787-829. [ Links ]

Salazar, C. F. (1999). In their own voice: The experience of counselor educators of color in academe (educators of color). Dissertation Abstracts International, 60(07), 07A. (University Microfilms No. AAG99-38987). [ Links ]

SAS Institute. (2000). JMP: Statistical Discovery Software [computer software]. Cary: Author. [ Links ]

Schaef, A. W. (1992). Beyond therapy, beyond science: A new model for healing the whole person. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Schaef, A. W. (1999). Living in process: Basic truths for living the path of the soul. New York: Ballantine Wellspring. [ Links ]

Sciarra, D. T. (1999). Multiculturalism in counseling. Itasca: F. E. Peacock. [ Links ]

Siegel, S., & Castellan Jr., J. N. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Smaby, M. H., Maddux, C. D., Torres, E. & Zimmick, R. (1997). Skilled Group Counseling Scale. Unpublished instrument, University of Nevada, Reno. [ Links ]

Smaby, M. H., Maddux, C. D., Torres-Rivera, E., & Zimmick, R. (1999). A study of the effects of a skills-based versus a conventional group counseling training program. Journal of Specialist in Group Work, 24, 152-163. [ Links ]

Sprinthall, R. C. (1997). Basic statistical analysis (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Srebalus, D. J., & Brown, D. (2001). A guide to the helping professions. Needham: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Sue, D. W. (1997). Foreword. In D. B. Pope-Davis, & H. L. K. Coleman (Eds.), Multicultural counseling competencies: Assessment, education and training, and supervision (pp. ix-xi). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counseling the culturally different (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Sue, D. W., Ivey, A. E., & Pedersen, P. B. (1996). A theory of multicultural counseling and therapy. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

The university of Alabama (n.d.). Counselor education [On-line]. Available: http://education.ua.edu/psych/counselor/index.html. Retrieved: April 21, 2004. [ Links ]

The university of Nevada (n.d.). The instructional homepage of Dr. Marlowe Smaby [On-line]. Available: http://education.ua.edu/psych/counselor/index.htm Retrieved: April 21, 2004. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E. (2001a). Information [On-line]. Available: Leved: November 14, 2001. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E. (2001b). Honesty [On-line]. Available: cesnetl@listserv.kent.edu. reatnetl@lists.ufl.edu. Retritrieved: November 26, 2001. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E. (2001c, September). Honestidad: El ingrediente necesario en la preparación de consejeros (a) profesionales. Paper presented at the National Annual Conference of the Asociación Puertorriqueña de Consejería Profesional, Dorado, Puerto Rico. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Phan, L. T., & Garrett, M. T. (2000). Who is teaching multicultural counseling studies? Journal of the Pennsylvania Counseling Association, 3, 33-42. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Phan, L. T., Maddux, C., Wilbur, M. P., & Garrett, M. (2001). Process versus content: Integrating personal awareness and counseling skills to meet the multicultural challenge of the 21st Century. Counselor Education and Supervision Journal, 41, 28-40. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Wilbur, M. P., Maddux, C., Smaby, Phan, L. T. & Roberts- Wilbur, J. (2002) Factor structure and construct validity of the Counselor skills personal development rating form (CSPD-RF). Counselor Education and Supervision Journal, 41, 268-278. [ Links ]

Truax, C., & Carkuff, R. (1967). Toward effective counseling and psychotherapy. New York: Aldine. [ Links ]

Urbani, S., Smith, M. S., Smaby, M., Maddux, C., Torres-Rivera, E., & Crews, J. (2002). Skill based training and counseling self-efficacy. Counselor Education and Supervision Journal, 42, 92-106. [ Links ]

Vacc, N. A., & Loesch, L. C. (1993). A professional orientation to counseling (2nd ed.). Bristol: Accelerated Development. [ Links ]

Wilbur, M. P. (1992, October). Honesty: The necessary but missing ingredient in multicultural counseling. Paper presented at the Northeastern Educational Research Association Conference, Ellenville, USA. [ Links ]

Wilbur, M. P., & Roberts-Wilbur, J. (1986). Honesty: Expanding skills beyond professional roles. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 24, 130-43. [ Links ]

Wilbur, M. P., Roberts-Wilbur, J., Hart, G. M., Morris, J. R., & Betz, R. L. (1994). Structured group supervision (SGS): A pilot study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 33, 262-279. [ Links ]

Wilbur, M. P., Roberts-Wilbur, J., Morris, J. R., Betz, R. L., & Hart, G. M. (1991). Structured group supervision: Theory into practice. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 16, 91-100. [ Links ]

Winddance Twine, F., & Warren, J. W. (Eds.). (2000). Racing research, research race: Methodological dilemmas in critical race studies. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Yalom, I. D. (1995). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (4th ed.). New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Received 20/05/2005

Accepted 20/10/2005

Edil Torres Rivera. Ph.D. in Counseling Psychology with a concentration in multicultural counseling from the University of Connecticut, Storrs. He is an associate professor at the University of Florida. Edil Torres Rivera research interests are multicultural counseling, group work, chaos theory, liberation psychology, technology, supervision, multicultural counseling, prisons, and gang-related behavior

1 Address: University of Florida, Department of Counselor Education, 1215 Norman Hall, P.O. Box 117046, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

E-mail: edil0001@ufl.edu.

2 See University of Alabama at http://education.ua.edu/psych/counselor/index.html and University of Nevada, Reno at

http://unr.edu/homepage/smaby/syl795.html for examples of syllabi.