Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versão impressa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.43 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2009

Wisdom in multicultural counseling: the omitted ingredient

Sabiduría en la consejería multicultural: el ingrediente omitido

Loan T. PhanI; Edil Torres RiveraII,1; Martin VolkerIII; Cleborne D. MadduxIV

IUniversity of New Hampshire, USA

IIUniversity of Florida, USA

IIIUniversity at Buffalo-SUNY, New York, USA

IVUniversity of Nevada, USA

ABSTRACT

This study explored the relationship between wisdom and multicultural counseling expertise. Wisdom was defined by Hanna, Bemak, and Chi-Ying Chung (1999) and measured by the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (Hy & Loevinger, 1996) and multicultural counseling expertise was measured by the Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (D'Andrea, Daniels, & Heck, 1990) among counselors-in-training. Specifically the study consisted of 45 counselors-in-training and was conducted based on the assumption that the acquisition of wisdom was the primary tool used by ancient civilizations to teach healers about human conditions. The findings indicated that levels of wisdom were statistically significant and accounted for 14% of the explained variance in the Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (D'Andrea et al., 1990).

Keywords: Wisdom; Multicultural counseling; Training.

RESUMEN

Este estudio exploró la relación entre la sabiduría y la pericia en consejería multicultural. La sabiduría fue definida de acuerdo a Hanna, Bemak, y Chi-Ying Chung (1999) y medida por Washington University Sentence Completion Test (Hy & Loevinger, 1996) y la pericia en consejería multicultural fue medida por el Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (D'Andrea, Daniels, & Heck, 1990) entre consejeros en entrenamiento. Específicamente el estudio consistió de 45 consejeros en entrenamiento y fue realizado basado en la creencia de que la adquisición de la sabiduría fue el instrumento primario utilizado por antiguas civilizaciones para enseñar a los curandero/as acerca de las condiciones humanas. Las conclusiones indicaron que los niveles de sabiduría fueron estadísticamente significativas y justificaron el 14% de la variación explicada en el Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (D'Andrea et al., 1990).

Palabras clave: Sabiduría; Consejería multicultural; Entrenamiento.

Wisdom has been the primary tool used by ancient civilizations to teach healers about human conditions. However, limited information is found in the counseling literature on how to teach wisdom as part of a counseling training program and even less can be found on how wisdom is defined. In 1999, Hanna, Bemak, and Chung presented an innovative model that targeted wisdom as an essential ingredient in counselor training by challenging as well as moving beyond traditional didactic methods of teaching multicultural counseling, meaning that will help counselors to put into practice effective multicultural counseling interventions. However, innovative and ground breaking the article and the model presented in the article, it was lacking in empirical evidence about the effectiveness of the model and how to implement such a training program in universities and in other training settings. Therefore, in a preliminary effort to develop a wisdom based model to train counselors as effective multicultural counselors, this study investigated wisdom and its contribution to multicultural counseling expertise. Furthermore, while multicultural models of counseling have been found to be important given the need to work in a multi-ethnic, global society, a number of studies suggested that in the United States multicultural counseling training seems to rely on teaching awareness and knowledge while neglecting the action piece and in fact sometimes counselors and therapists appear to be maintaining the status quo (Aldarondo, 2007; Toporek & Sloan, 2007).

This study comes at a time when the multicultural counseling movement has taken a new direction towards specific competencies to acquire culture specific knowledge, awareness, and skills as a prerequisite for effective multicultural counseling (Arredondo & Rosen, 2007; Sue & Sue, 2003). This new turn appears to neglect the findings of a number of studies that have reportedly demonstrated that a counselor's personal characteristics have a greater impact on the client's outcome than specific skills and/or theoretical approaches (Hanna et al., 1999; Martinez, 1994; Torres-Rivera, Wilbur, Phan, Maddux, & Arredondo, 2006). At the same time in the Unites States the multicultural counseling movement has been equally criticized supposedly, due to inability of multicultural counselors to rule out psychopathology in ethnic minority clients at the same rate or with the same standards than with clients from the dominant culture, which according to critics has to do with multicultural counselors being more concerned with liberal political agendas than mental health issues (Weinrach & Thomas, 2002). In other words, according to Weinrach and Thomas (2002), a number of people in the United States believe that the multicultural counseling movement is not about mental illness but is about the politics of counseling. Some with this belief are opposed to the idea that oppression in any shape or form is toxic and demeaning. The authors of this study also propose that pursuing skills development exclusively, as many training programs have done, is as ineffective as is looking for psychopathology in every treatment. Hanna et al. (1999) proposed that the concept of wisdom might have significance in the development of effective multicultural counselors.

Wisdom and Intelligence Background

Wisdom has a special place in the multicultural arena because it emphasizes a certain kind of rich, deep, and fluid understanding (Phan, 2001). Being able to integrate the diversity and richness of experiences may help an individual become aware of the universality of our humanness and the cultural heritage that is unique in each individual and her or his own qualities. Research that was done to examine the core conditions of the effective counselor included positive regard, genuineness, empathy, honesty, and concreteness (Carkhuff, 1969a, 1969b; Carkhuff & Berenson, 1977; Torres-Rivera et al., 2006; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). The need for multicultural counselors to gain wisdom requires the inclusion of these conditions as well as the transcendence of them (Torres-Rivera et al., 2006). This ability to exceed a counselor's development of positive regard, genuinesss, empathy, honesty, and concretness also involves advanced empathy to express understanding to a client that extends beyond mere reflecting and para-phrasing (Ottens, Shank, & Long, 1995). The component of wisdom is vital (Kramer 1997, 2000; Pascual-Leone, 1997; Sternberg, 1997; Sternberg & Jordan, 2005) and a necessary element to build a strong base for effective multicultural counseling (Hanna et al., 1999; Phan, 2001; Torres-Rivera et al., 2006).

While a number of people usually equate intelligence with wisdom, Kunzmann and Baltes (2005) indicated otherwise. That is intelligence is defined in a number of different ways, from the ability of people to understand complex ideas, to effectively adapt to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning and to overcome obstacles by taking thought. However, wisdom requires an integration of different types of knowledge in balance (Kunzmann & Baltes, 2005). Furthermore, intelligence usually refers to cognitive abilities and not as expertise in the pragmatics of life (Sternberg & Jordan, 2005). Additionally, it is important to point out that the value and importance given to intelligence based on technology, mathematics, and the hard sciences have led Western education to overlook the aspect of wisdom.

Therefore, to re-emphasize the definition of wisdom and how it fits into the training of multicultural mental health professionals, wisdom is integrative and holistic; it refers to the outstanding functioning and it directs the person's behavior in ways that simultaneously the person's own potential and of others around her or him(Kunzmann & Baltes, 2005), thus "if the characteristics of wisdom are indeed remarkably similar to the characteristics of the effective counselor, then exploring and developing training methods based on wisdom maybe a worthy task" (Hanna et al., 1999, p. 131).

To decipher what constitutes effective counseling, training methods that integrate wisdom may offer a more comprehensive perspective. The present study is needed because graduate training has not been able to produce counselors and therapists who are more effective than less trained paraprofessionals. Extensive research has shown that regardless of education level, years of experience, and level of training that professionals hold over paraprofessionals, the effectiveness of professionals is no greater than effectiveness of paraprofessionals (Berman & Norton, 1985; Christensen & Jacobson, 1994; Dawes, 1994; Hattie, Sharpley, & Rogers, 1984; Humphreys, 1996; Peterson, 1995).

Other researchers argued that the effectiveness of therapists who received years of graduate level training were only slightly greater than paraprofessionals (Stein & Lambert, 1995). These investigators also noted that evidence to uphold current training methods were nonexistent. In an unrelated study but relevant to the present study, Loevinger and Wessler (1970) found in the studies they conducted on helping professionals' development that the moral developmental stages of helping professionals were no higher than the population at large. If we combined the Loevinger and Wessler (1970) findings with the assumption that Lovienger's developmental scheme and the characteristics of wisdom correspond to one another (Kramer, 1997, 2000) and if we accept that this phenomenon is not unique to helping professionals but is similarly distributed throughout the population, then we are forced to admit that mental health professionals may be missing an aspect of their training that would prepare them to deal with multicultural or multiethnic populations. That aspect is wisdom.

For that reason and for this particular study, the researchers asked "What variable can account for the difference between effective and ineffective multicultural counselors?" Hanna et al. (1999) stress that "if training programs were capable of developing wisdom in students, those programs would also be turning out more effective counselors" (p. 131). Therefore, the researchers believe that a highly effective multi-cultural counselor is equivalent to a wise multicultural counselor. Moreover, a concentration and emphasis on the concept of wisdom could relieve the dilemmas highlighted in the studies on professionals and para-professionals and the critiques of current methods of multicultural training models.

Kramer (1997, 2000) asserted that an individual who possesses the characteristics at the higher stages of development in Loevinger's scheme (self-aware, conscientious, individualistic, autonomous, and integrated) also has the characteristics associated with wisdom, addresses the question of how wisdom can be measured. The characteristics of ego development are subdivided in three different dimensions or domains. The description of the characteristics for self-awareness are as follows: the main characteristic under impulse control is "exceptions are allowed. These three domains are: (a) impulse control; (b)interpersonal mode; and (c) conscious preoccupation. For the interpersonal mode in self-aware the characteristics are "helpful and self-aware". For the domain of conscious preoccupation for the self-aware stage the characteristics are "feelings, problems, and adjustment".

For the stage of conscientious, the main characteristic under impulse control is "self-evaluated standards and self-critical". For the interpersonal mode in conscientious the characteristics are "intense and responsible". For the domain of conscious preoccupation in the conscientious stage the characteristics are "motives, traits, and achievements".

The next stage in the Loevinger model (1998a) is the individualistic stage where the main characteristic under impulse control is "tolerant". The characteristic for the interpersonal mode in the individualistic stage is "mutual". For the domain of conscious preoccupation in the individualistic stage the characteristics are "individualistic, development, and roles".

In the autonomous stage the main characteristic under impulse control is "coping with conflict". For the interpersonal mode in the individualistic stage the characteristic is "interdependent". For the domain of conscious preoccupation for this stage the characteristics are "self-fulfillment and psychological causation".

The final stage is the stage of integrated. Here under the impulse control domain Loevinger (1998a) does not offer a characteristic, probably assuming that this is no longer an issue in this higher stage of moral development. For the interpersonal mode in the integrated stage the characteristics are "cherishing individuality". For the domain of conscious preoccupation for this stage the characteristic is "identity".

The brief description of the ego development characteristics as described by Loevinger and the definitions of wisdom given earlier in the article suggest that developing wisdom requires the element of ego development, which is also known as character development (Loevinger, 1985). This leads the authors of this article to the conclusion that it will be beneficial to measure and to determine the present and the overall levels of wisdom in training or supervision using the Washington University Sentence Completion Test of ego development (Loevinger, 1976, 1985; Loevinger & Wessler, 1970; Loevinger, Wessler, & Redmore, 1970).

Furthermore, while much progress has been made in training multicultural counselors in the United States (Cartwright, Daniels, & Zhang, 2008), several social scientists have contended that traditional and existing theories and practices of multicultural counseling have been harmful and remain inadequate (Crethar, Torres Rivera, & Nash, 2007; Duran, Firehammer, & Gonzalez, 2008). Current multicultural courses and traditional curricula have neglected the aspect of wisdom and continue to focus mainly on intelligence as the foundation of their training methods (Torres-Rivera et al., 2006).

Unfortunately, this results in students who are capable of "[espousing] the appropriate rhetoric and present poli-tically correct language" (Hanna et al., 1999, p. 133), but not in helping their multicultural/multiethnic clients to get better. Sue and Sue (2003) stated that if training multiculturally competent and effective counselors were merely a matter of acquiring cultural awareness, knowledge and skills, then racism would have been eliminated years ago. Since our assumptions, prejudices, biases, and stereotypes extend beyond simply procuring information and technical skills, an emphasis and enhancement in wisdom (indicating pragmatics and balance) by training programs could move the counseling field to a level of effectiveness that has yet to be reached (Wilbur, 2002).

Moreover, the notion of wisdom as a comprehensive perspective associated with multicultural counseling effectiveness has been ignored in the literature on effective counseling. The lack of emphasis on this missing ingredient has obscured the understanding and investigation of what constitutes proper training for effectiveness in the field of multicultural counseling. A wise multicultural counselor has the ability to integrate new learning and experiences into diverse ways of thinking and understanding of oneself and others. Sternberg (1997) included the following characteristics in his view of wisdom: (a) ability to listen; (b) have a concern for others; (c) behavioral maturity (it is the ability of a person to develop an unusual degree of sensitivity, broad-mindedness, and concern for humanity); (d) understanding others in a deep, psychological way; (e) self-awareness; (f) self-knowledge; (g) empathy; (h) acknowledging and learning from one's mistakes; and (i) reframing meanings (for specific definitions please see Sternberg, 1997; Sternberg & Jordan, 2005). The many issues and topics that are involved in multicultural counseling require counselors to constantly monitor and incorporate contrasting values, attitudes, beliefs, worldviews, traditions, customs, perceptions, assumptions, biases along with our collective fundamental human qualities.

Finally, one must keep in mind that wisdom is not a modern concept but rather an ancient, transcultural concept that has been discussed long before it surfaced in the Western behavioral sciences in the 1980s (Hanna et al., 1999). In contrast to the drop in radical behaviorism and logical positivism, researchers in particular fields such as human development and intelligence have begun to investigate the concept of wisdom (Kunzmann & Baltes, 2005; Robinson, 1997). Although some researchers (Blocher, 1983; Ivey, 1986) have looked at specific aspects of wisdom, such as the dialectical and developmental, they have not espoused wisdom in its entirety.

In terms of problem solving, Arlin (1997) noted that this cognitive ability refers to one's capacity to identify a problem and formulate a solution in such a way that no other problems arise. Similarly, Kramer (1997, 2000) contended that wisdom involves an awareness and identification of feelings and emotions. According to Hanna and Ottens (1995) and Kramer (2000), the aforementioned characteristics and defini-tions of wisdom are associated with being an effective counselor.

Earlier in this article, we began to establish the difference between intelligence and wisdom. It is important to re-establish these differences at this time. Hanna et al. (1999) make this differentiation to emphasize that wisdom is more essential than intelligence with respect to effective counseling. Meacham (1983) suggests wisdom consists of knowing one's limitations, knowing what one knows and does not know, and knowing what one can know and cannot know. On the other hand, intelligence focuses on analyzing, recalling, and using knowledge (Meacham, 1983).

Sternberg (1997) discusses ambiguity with respect to wisdom and states that a wise individual is at ease with ambiguity, in contrast to an intelligent individual who believes that ambiguity needs to be resolved - and the sooner the better. Individuals at higher stages of development are able to tolerate ambiguity more effectively than persons with less developed psychological dispositions. Resolution of ambiguity with wisdom permits the emergence of clarity to resolve ambiguity without the need to diminish or oversimplify situations (Hanna, Giordano, & Bemak, 1996). Consequently, the authors of this article have the following questions as the guides for this particular preliminary study:

The research questions for this study were:

Research Question 1. To what extent and in what manner can variation in the level/degree of multicultural counseling expertise (as measured by the MAKSS) be explained by the level/degree of wisdom among counselors-in-training (as measured by the WUSCT)?

Research Question 2. How does wisdom in counselors-in-training affect multicultural counseling expertise

Method

Participants

There were 45 participants, 36 females and 9 males. The sample was composed of 6 Asian Americans, 4 Latino/Hispanic, 2 biracial, and 33 Caucasian partici-pants. The mean age of the participants was 32.73, median age 29.00, modal age 27.00, range 23 to 55, and standard deviation 8.99. The participants were selected from a pool of more than 200 counselor trainees enrolled in a counselor education program accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Programs (CACREP) at a mid-size public western university. The sample was one of convenience. All of the participants had completed at least 48 credits of their 60-credit hour program, including a theory course and a 100-hour practicum.

Instruments

The Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (MAKSS) (D'Andrea, Daniels, & Heck, 1990) was used to measure the level of multicultural expertise of the research participants. The MAKSS measures an individual's multicultural counseling expertise in three areas: (a) awareness; (b) knowledge; and (c) skills. Three mean subscale scores are generated from the MAKSS. The MAKSS is a self-report survey that consists of 60 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale. There are three subscales of awareness (i.e., item number 3: At this time in your life, how would you rate yourself in terms of understanding how your cultural background has influenced the way you think and act?), knowledge (i.e., item 35: In the early grades of normal schooling in the United States, the academic achievement of such ethnic minorities as African Americans, Latinos, and American Indians is close to parity with achievement of White mainstream students.), and skills (i.e., item 43: How well would you rate your ability to distinguish "formal" and "informal" counseling strategies?). Responses show the counselor trainees' agreement or disagreement about their level of awareness of multicultural issues, the self-ratings on their level of understanding of multicultural counseling terms and topics, and the self-ratings on their level of multicultural counseling skills. The ranking of these choices range from 1 (strongly disagree or very limited), 2 (disagree or limited), 3 (agree or good), and 4 (strongly agree or very good), and total scores include subscale scores (awareness subscale in items 1 to 20; knowledge subscale in items 21 to 40; and skill subscale in items 41 to 60). The sum is divided by 20 to produce three subscale scores. Seven items that are negatively worded are scored in reverse. The MAKSS full scale reliability was reported as .87 (Díaz-Lázaro & Cohen, 2001) and for this study was calculated as .88.

The Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT) (Hy & Loevinger, 1996) was included to measure wisdom, as defined by Hanna et al. (1999) and supported by Sternberg (1997). The WUSCT is a self-reported test containing 36 items that measure ego or character development. The WUSCT identifies eight stages of ego development based upon sentence completion responses. As explained earlier, the highest level of ego development was equated with wisdom based on the characteristics associated with that stage. Each item is associated with one of eight ego levels: (a) impulsive; (b) self-protective; (c) conformist; (d) self-aware; (e) conscientious; (f) individualistic; (g) autonomous; and (h) integrated. The sum of all 36 items determines an individual's overall ego level. While the purpose of the WUSCT is to measure ego development, according to Hanna et al. (1999) the characteristics of each level of ego development can be equated with wisdom. For example, a person in the impulsive level of ego development will exhibit characteristics such as impulsiveness, egocentricity, dependency, and preoccupation with bodily feelings. This stage is farther away from wisdom because the person is more concerned with themselves and is searching for personal answers and not necessarily in balance or looking for questions for humankind. In contrast, a person in the autonomous stage or level of ego development will exhibit characteristics such as coping with conflict, interdependence, and preoccupation with self-fulfillment and psychological causation, which when looking at the definitions of wisdom could be equated with wisdom. In fact Staudinger, Dörner and Mickler (2005) cited a number of studies where Loevinger's ego development scale can be operationalized as personal wisdom.

The WUSCT, which was developed by Loevinger in 1950, has undergone a number of changes to improve validity and reliability. When using the total score of all 36 items, the alpha coefficient reliability of the WUSCT was .58 and the validity consistently fell between .84 to .96 (Loevinger, 1998b). For this study, the alpha coefficient was .86.

Research Design and Procedure

Participants were recruited from three different multicultural classes. As stated earlier the participants had completed at least 48 credits of the required 60 credit hours degree programs. Prerequisites for the multicultural counseling course included personality theory, human development, and at least one practicum or fieldwork course.

The two instruments used to measure the variables in the study (WUSCT and MAKSS) were distributed to the participants at the end of three different multicultural counseling courses on three different occasions. A demographic questionnaire was also distributed in conjunction with the instruments. Issues of confidentiality and privacy were dealt with by following university human subjects procedures in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations.

The criterion variable or dependent variable was multicultural counseling expertise in its totality (awareness, knowledge, and skills) as measured by the MAKSS. The independent variables included the following: (a) age; (b) ethnicity; (c) religion; (d) program (marriage and family counseling, school counseling, college student development, and substance abuse counseling); (e) gender; (f) ethnicity; (g) occupation; (h) group dynamics; and (i) wisdom (as measured by the WUSCT).

Two stepwise multiple regression was used to determine which variables could be used as significant predictors of multicultural expertise.

Results

Results of Testing Exploratory Research Question 1. To what extent and in what manner can variation in the level/degree of multicultural counseling expertise (as measured by the MAKSS) be explained by the level/degree of wisdom among counselors-in-training (as measured by the WUSCT)?

The regression analyses indicated that the contri-bution of the level of wisdom as measured by the WUSCT was statistically significant and accounted for 14% of the explained variance in the total scores of the MAKSS. The specific contribution, along with the analyses, is explained in detail below.

To answer the first exploratory research question, a standard regression was conducted for the total score of the Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills Survey (D'Andrea, Daniels, & Heck, 1990). The regression carried two different hypotheses. First, to what extent was the level/degree of multicultural expertise explained by the level/degree of wisdom (Ho: R = 0 or Ho: R2 = 0). Second, in what manner were variations in the degree/level of multicultural expertise explained by the degree/level of wisdom (Ho: B = 0 or Ho: b = 0). Predictor variables for the regression were: (a) age; (b) ethnicity; (c) religion; (d) program (marriage and family counseling, school counseling, college student development, and substance abuse counseling); (e) gender; (f) ethnicity; (g) occupation; (h) group dynamics; and (i) wisdom.

The stepwise regression analysis indicated that the following independent variables did not contribute sufficiently to the explained variance of multicultural counseling expertise in order to enter the analysis: (a) ethnicity; (b) religion; (c) program (marriage and family counseling, school counseling, college student development, and substance abuse counseling); (d) gender; (e) ethnicity; (f) occupation; and (g) group dynamics. Therefore, with the exception of age, all other sociodemographic variables played insignificant roles in explaining multicultural counseling expertise in this study.

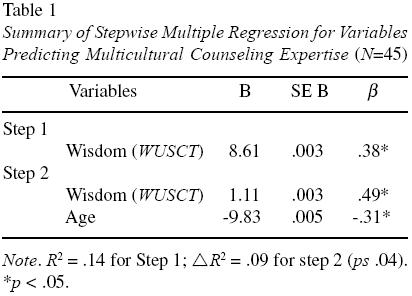

The regression also indicated that the amount of explained variance between the two independent variables (age and wisdom) and multicultural counseling expertise was 23%. The contribution of the level of wisdom was 14%, while the contribution of age was 9% (see Table 1).

Results of Testing Exploratory Research Question 2. How does wisdom in counselors-in-training affect multicultural counseling expertise?

To answer the second research question that explored how wisdom may affect multicultural counseling expertise, the analyses indicated that most of the sociodemographic variables did not have an impact on multicultural counseling expertise. However, the analysis indicates a positive relationship between level of wisdom and level of multicultural counseling expertise (β = .38, t (2.66) = 7.09, p < .01). A negative relationship between age and level of multicultural counseling expertise was also observed (β = -.31, t (-2.15) = 6.15, p < .04).

Discussion

The two research questions explored relationships between wisdom and multicultural counseling expertise. The study presented evidence to support the claims of Hanna et al. (1999) that wisdom may affect counselors-in-training regarding their level of multicultural counseling expertise. The results also support the need for expanding multicultural counseling training beyond skilled based training programs to one that encompasses critical thinking and action (Torres-Rivera, Phan, Maddux, Wilbur, & Garrett, 2001; Wilbur, 2002).

In this study, the variables of ethnicity, gender, specialization (i, e., marriage and family counseling, addiction counseling, college student development, school counseling), occupation, group dynamics, and religion did not appear to play an important role in the overall explained variance of multicultural counseling expertise with counselors-in-training. This particular finding seems to diverge from popular belief that specialized counselors are more effective than generalists. In addition, data in this exploratory study show that a model based on teaching wisdom may help to alleviate the problem of imbalance between awareness, knowledge, and skills in multicultural training models, which is has been the criticism of multicultural models in the past (Torres-Rivera et al., 2001). The findings also imply that a model based on teaching wisdom can be an effective supervision format to assist counselors-in-training in improving not only their multicultural counseling expertise but their counseling skills in general by recognizing deficiencies and seeking improvement, which is one of the characteristics of wisdom.

There has been a great deal of discussion and research about how successful graduate programs have been in producing effective mental health professionals (Michie, Johnston, Francis, Hardeman, & Eccles, 2008). The results appear inconclusive and point to the fact that inadequate empirical evidence exists to support the belief that professionally trained counselors and therapists are more effective than paraprofessionals (Hanna et al., 1999). Furthermore, a recent study about a skill-based model indicated that the development of skills demonstrated entry level training but did not prepare counselor for advanced challenges during their practice in real life (Urbani et al., 2002). In other words, skilled-based programs do not prepare graduate level counselors-in-training to be any more effective than their para-professional counterparts. Consequently, a program that intentionally teaches wisdom will provide students not only with the tools of the trade, but also with the know-how, necessary for effective multicultural counseling. Incorporating wisdom into graduate programs involves preparing counselors-in-training to develop critical thinking, to be open and curious about the outer World, to other perspectives and cultural carriers such as books, arts, and wise people and helping them to link their past experiences with future reproduction (Csikszentmihalyi &Nakamura, 2005).

Limitations of the Study

There are a number of limitations noted in the present study. The small sample size of the study and consequent limited power is a limitation. In addition, participants consisted mainly of Caucasian female counselors-in-training, which limits the generalizability to persons in this gender group and not to counselors-in-training who come from a different ethnic background and/or gender.

Future Research

While this study provides some information about the relationship between a person's wisdom and multicultural counseling expertise, this is only one study, therefore more research is necessary to fulfill the need to better train counselors. Some future research studies might include a control group to compare different treatments (i.e., skills development models). Another direction for future research could involve the use of different assessment tools to investigate differences over time and relationships among multicultural counseling expertise, wisdom, and the specific development of counseling skills. Among the instruments that may be useful in this regard include but are not limited to the Counselor Evaluation Rating Scale (CERS) (Myrick & Kelly,1971), The Foundation Values Scale (Jason et al., 2001), and the Counselor Skill Personal Development Scale Rating Form (CSPD-RF) (Torres-Rivera et al., 2002).

Despite the preliminary nature of this study it appears that the investigation of wisdom as well as the need for action oriented training have some value in the preparation of mental health professionals. With the multicultural movement in the United States moving toward social justice and advocacy, the authors of this article assert that developing training models that require a more balanced and integrated approach of training for new professionals is a worthwhile effort.

References

Aldarondo, E. (Ed.). (2007). Advancing social justice through clinical practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Arlin, P. K. (1997). Wisdom: The art of problem finding. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 230-243). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Arredondo, P., & Rosen, D. (2007). Applying principles of multicultural competencies, social justice, and leadership in training and supervision. In E. Aldarondo (Ed.), Advancing social justice through clinical practice (pp. 443-458). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Berman, J. S., & Norton, N. C. (1985). Does professional training make a therapist more effective? Psychological Bulletin, 98, 401-407. [ Links ]

Blocher, D. H. (1983). Toward a cognitive developmental approach to counseling supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 11, 27-33. [ Links ]

Carkhuff, R. R. (1969a). Helping and human relations: A primer for lay and professional helpers: Vol. 1. Selection and training. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Carkhuff, R. R. (1969b). Helping and human relations: A primer for lay and professional helpers: Vol. 2. Practice and research. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Carkhuff, R. R., & Berenson, B. G. (1977). Beyond counseling and therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Cartwright, B., Daniels, J., & Zhang, S. (2008). Assessing multicultural competence: Perceived versus demonstrated performance. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 318-322. [ Links ]

Crethar, H., Torres Rivera, E., & Nash, S. (2008). In search of common threads: Linking multicultural, feminist, and social justice counseling paradigms. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 269-278. [ Links ]

Christensen, A., & Jacobson, N. S. (1994). Who (or what) can do psychotherapy: The status and challenge of nonprofessional therapies. Psychological Science, 5, 8-14. [ Links ]

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2005). The role of emotions in the development of wisdom. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 220-242). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

D'Andrea, M., Daniels, J., & Heck, R. (1990). The multicultural awareness, knowledge, and skills survey. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii. [ Links ]

Dawes, R. M. (1994). House of cards: Psychology and psychotherapy built on myth. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Díaz-Lázaro, C. M., & Cohen, B. B. (2001). Cross-cultural contact in counseling training. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29, 41-56. [ Links ]

Duran, E., Firehammer, J., & Gonzalez, J. (2008). Liberation psychology as the path toward healing cultural soul wounds. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 288-295. [ Links ]

Hanna, F. J., Bemak, F., & Chi-Ying Chung, R. (1999). Toward a new paradigm for multicultural counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 125-134. [ Links ]

Hanna, F. J., Giordano, F. G., & Bemak, F. (1996). Theory and experience: Teaching dialectical thinking in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 14-24. [ Links ]

Hanna, F. J., & Ottens, A. J. (1995). The role of wisdom in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 5, 195-219. [ Links ]

Hattie, J. A., Sharpley, C. E., & Rogers, H. J. (1984). Comparative effectiveness of professional and paraprofessional helpers. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 534-541. [ Links ]

Hy, L. X., & Loevinger, J. (1996). Measuring ego development (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Humphreys, K. (1996). Clinical psychologists as psychotherapists: History, future and alternatives. American Psychologist, 51, 190-197. [ Links ]

Ivey, A. E. (1986). Developmental therapy: Theory into practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Jason, L. A., Reicher, A., King, C., Madsen, D., Camacho, J., & Marchese, W. (2001). The measurement of wisdom: A preliminary effort. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 585-598. [ Links ]

Kramer, D. A. (1997). Conceptualizing wisdom: The primacy of affect-cognition relations. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 279-313). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kramer, D. A. (2000). Wisdom as a classical source of human strength: Conceptualization and empirical inquiry. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 83-101. [ Links ]

Kunzmann, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2005). The psychology of wisdom: Theoretical and empirical challenges. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 110-135). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L. (1976). Ego development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L. (1985). Revision of the sentence completion test for ego development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 420-427. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L. (1998a). History of the sentence completion test (SCT) for ego development. In J. L. Loevinger (Ed.), Technical foundations for measuring ego development: The Washington University sentence completion test (pp. 1-10). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L. (1998b). Reliability and validity of the SCT. In J. L. Loevinger (Ed.), Technical foundations for measuring ego development: The Washington University sentence completion test (pp. 29-40). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L., & Wessler, R. (1970). Measuring ego development: Vol. 1. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Loevinger, J. L., Wessler, R., & Redmore, C. (1970). Measuring ego development: Vol. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Martinez, C. (1994). Psychiatric treatment of Mexican-Americans: A review. In C. Telles & M. Karno (Eds.), Latino mental health: Current research and policy perspectives (NIMH Publication No. 94MF04837-24D, pp. 227-340). Los Angeles: University of California. [ Links ]

Meacham, J. A. (1983). Wisdom and the context of knowledge: Knowing that one doesn't know. In D. Kuhn & J. A. Meachum (Eds.), On the development of developmental psychology (pp. 111-134). Basel, Switzerland: Karger. [ Links ]

Michie, S., Johnston, M., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., & Eccles, M. (2008). From theory to intervention: Mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 660-680. [ Links ]

Myrick, R. D., & Kelly, D. F., Jr. (1971). A scale for evaluating practice students in counseling and supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 12, 330-336. [ Links ]

Ottens, A. J., Shank, G. D., & Long, R. J. (1995). The role of adductive logic in understanding and using advanced empathy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 34, 199-211. [ Links ]

Pascual-Leone, J. (1997). An essay on wisdom: Toward organismic processes that make it possible. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 244-278). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Peterson, D. R. (1995). The reflective educator. American Psychologist, 50, 975-983. [ Links ]

Phan, L. T. (2001). Structured group supervision from a multicultural perspective. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, NV. [ Links ]

Robinson, D. N. (1997). Wisdom through the ages. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 13-24). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Staudinger, U., Dörner, J., & Mickler, C. (2005). Wisdom and personality. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 191-219). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Stein, D. M., & Lambert, M. J. (1995). Graduate training in psychotherapy: Are therapy outcomes enhanced? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 182-196. [ Links ]

Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1997). Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sternberg, R. J., & Jordan, J. (Eds.). (2005). A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counseling the culturally different: Theory and practice (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Toporek, R., & Sloan, T. (2007, Spring). On social action in counseling and psychology: Visions for the Journal. Retrieved September 18, 2008, from http://www.psysr.org/jsacp/sloan-toporek-v1n1.htm [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Phan, L. T., Maddux, C. D., Wilbur, M. P., & Arredondo, P. (2006). Honesty the necessary ingredient in multicultural counseling: A pilot study of the counseling relationship. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 40(1), 37-45. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Phan, L. T., Maddux, C. D., Wilbur, M. P., & Garrett, M. (2001). Process versus content: Integrating personal awareness and counseling skills to meet the multicultural challenge of the 21st Century. Counselor Education and Supervision Journal, 41, 28-40. [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E., Wilbur, M. P., Maddux, C., Smaby, M., Phan, L. T., & Roberts-Wilbur, J. (2002). Factor structure and construct validity of the Counselor skills personal development rating form (CSPD-RF). Counselor Education and Supervision, 41, 268-278. [ Links ]

Truax, C. B., & Carkhuff, R. R. (1967). Toward effective counseling psychotherapy. Chicago: Aldine. [ Links ]

Urbani, S., Smith, M. S., Smaby, M., Maddux, C., Torres-Rivera, E., & Crews, J. (2002). Skill based training and counseling self-efficacy. Counselor Education and Supervision Journal, 42, 92-106. [ Links ]

Weinrach, S. G., & Thomas, K. R. (2002). A critical analysis of the multicultural counseling competencies: Implications for the practice of mental health counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 24, 20-35. [ Links ]

Wilbur, M. P. (2002). Rivers of a wounded heart: Every man's journey. Herndon, VA: Capital Books. [ Links ]

Received 03/12/2007

Accepted 04/09/2008

Loan T. Phan. University of New Hampshire, USA.

Edil Torres Rivera. University of Florida, USA.

Martin Volker. University at Buffalo-SUNY, New York, USA.

Cleborne D. Maddux. University of Nevada, USA.

1 Address: University of Florida, Department of Counselor Education, 1215, Norman Hall, P. O. Box 117046, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2611-7046. Phone: 352-392-0731, ext. 256; Fax: 352-846-2697. E-mail: edil0001@ufl.edu