Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Junguiana

versión On-line ISSN 2595-1297

Junguiana vol.39 no.1 São Paulo ene./jun. 2021

Paintings of a psychiatric patient: the Uncountable States of Being

Sergio Luiz Alécio FilhoI; Regina Helena Lima CaldanaII

IGraduated

psychologist from the University of São Paulo (FFCLRP/USP), analyst candidate

to the Institute of Analytical Psychology of Campinas (IPAC), connected to the

Jungian Association of Brazil (AJB) and to the C.G. Jung International Association

for Analytical Psychology (IAAP). Former intern at the Museum of Images of the

Unconscious of Rio de Janeiro. email: <sergio_aleciofilho@yahoo.com.br>

IIGraduated psychologist from the University of São Paulo

(FFCLRP/USP), master and doctor in Education from the Federal University of

São Carlos (UFSCar), professor at the Department of Psychology at the

Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Languages, University of São Paulo

at Ribeirão Preto (FFCLRP/USP). email: <rhlcalda@ffclrp.usp.br>

ABSTRACT

Art is a form of communication and symbolic expression and an instrument for understanding the human being. The objective of this article is to analyze the visual media production of a psychiatric patient, seeking to understand the material as an expression of his psychic dynamics. A case study was carried out with a visitor of a community center in a psychiatric hospital in the state of São Paulo. Some works of art were chosen for the study after participative observation in the studio. To assist in the analysis of the paintings, an interview was conducted with the participant, focusing on his life story and comments regarding the art he produced. Through painting, it was noticed that there was a depotentialization of threatening content from the patient's psyche. It can also be observed that painting provided an expressive space for the participant to deal with fantasies of his internal world.

Keywords: art, panting, psychic dynamics, de-potentialization.

Introduction

We can say: the painting as a method of research, the painting as a method of treatment (Nise da Silveira)1

Art is a form of communication and symbolic expression and an important instrument for the understanding of human beings, of their conflicts and their potentials.

Free expression, through drawing, painting and modeling, in the field of Psychiatry and Psychology, has become of scientific interest, due to, among other reasons, its potential as a less difficult means of access to the psychiatric patient's internal world (SILVEIRA, 1982).

Currently, expressive resources are used therapeutically in psychiatric centers. In the recent past, Classical Psychiatry has had little interest in the wealth of the inner world of patients with mental disorders. The treatment incorporated violent methods, such as electroshock as a punishment, which increasingly affected the patient's self-image, worsened the disorder and harmed their creativity. An excess of psychotropic drugs was also used, which left patients emotionally numb with a subsequent reduction in creative capacity.

Classical Psychiatry's view was centered only on the disease of individuals and considered organic causes as the source of any dysfunction of the organism. That approach began to be criticized as being reductionist, as it leaves aside emotional factors that could be involved in mental disorders. This conception is well defined in the following statement by Capra (1998), who defends an integrated view of the human being: "Psychiatrists, instead of trying to understand the psychological dimensions of mental illness, focus their efforts on finding organic causes for all mental disorders" (p. 123).

Thus, patients were labeled and hospitalized without searching for causes that led them to develop their condition, such as affective, family-related and economic problems, which are interpersonal and socio-cultural factors involved in the disorder's development. In addition, the disease was treated as a symptom and not as a possible revelation of meaning in the person's life trajectory, which Jung, particularly, demonstrated clearly when referring to psychotic conditions.

This notion gradually changed, and in Brazil, mainly by the end of the 20th century, with the anti-asylum movement, it gained new strength. This movement proposes a humanized, effective treatment and preferably the absence of full hospitalization, due to the loss of autonomy and citizenship rights that happens during the process. However, hospitalization is recommended in cases of absolute necessity and with the consent of the patient and their family. The main motto of the anti-asylum struggle is to treat and not to socially exclude the individual, always seeking possibilities of resocialization.

Psychiatrist Paulo Amarante (1999) affirms that the goal of the psychiatric reform "... is not only the humanization of relationships between subjects, society and institutions... the objective that we seek is to build a new social place for madness, for difference, diversity, divergence" (p. 49). According to Bastos (1993), this new social place can be found if madness were to be socially re-signified and seen from other angles. In this sense, it is important to consider that in the world of the so-called "crazy", imagination prevails and its spirit flows in the midst of contradictions and inconsistencies, which only appear as such to the common man. Thus, the knowledge about madness tends to expand through the study of these ramblings, since hallucinations and illusions are symbolically rich materials that can be used, creating possibilities of expansion for the human psyche (BASTOS, 1993).

In contrast to the Classical Psychiatry, the therapeutic method developed by Dr. Nise da Silveira (Maceió, 15th of February, 1905 - Rio de Janeiro, 30th of October, 1999), a psychiatry from Alagoas and pioneer on the ideas of Jung in Brazil, which used painting, drawing, collage, modeling, music and, craft work, proves to be an extremely useful alternative, with possibilities tuned to the psychiatric reform proposals.

Paul Klee, contemporary painter, states that "painting allows the invisible to become visible" (KLEE apud SILVEIRA, 1982, p.39). This phrase refers to the presence of the unconscious in artwork, which is of importance to researchers and therapists who, in the analysis of paintings, can observe the presented contents of the unconscious, which reveals the state of the psyche and the functioning of the psychic dynamics of those who paint. In addition, one must be aware of social factors and interconnected intrapsychic phenomena, context builders of patients' experiences and made visible through painted images.

Nise da Silveira worked towards free expression as a means of instrumentalizing human development. Through her practice with psychiatric patients, she saw an improvement in general condition, including in her clients interpersonal relationships (SILVEIRA, 1992). She was one of the pioneers to develop the use of methods of expressive resources for therapeutic functions in Brazil, in her activities at the psychiatric hospital D. Pedro I, in Engenho de Dentro. She founded the Casa das Palmeiras and the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente (Museum of Images of the Unconscious), where the clients' artistic productions have been preserved. It also has the world's largest collection of works by psychiatric patients.

Unlike traditional psychiatric practice, Nise saw clients as developing beings and criticized the denominations assigned to schizophrenics, such as emotional bluntness, which can still be found in psychiatric textbooks today. She even refused to use the word 'patient' to refer to people committed to the hospital and preferred the term 'clients', in order to avoid conveying the meaning of 'passivity'. Empirically, she observed in the painting studios that schizophrenics showed affection in the proposed activities and in the relationships with the workshop monitors. She realized that it is at the affective level that the individual's transformation can occur; she resorted to a chemistry term, saying that "affection is a catalyst for human development". During her practice, she referred to her working method as "the emotion of dealing", and preferred to replace the name "schizophrenia" for "countless states of being". Nise stated that "the best medicine is human contact, affection in relationships; what cures is joy, the lack of prejudice" (SILVEIRA, 1992).

According to Nise Silveira (1992), "art will remove things from this disturbing whirlwind" of the patient's psyche. This whirlwind expresses, in various art forms, fragments of the disorderly-living drama, thus giving shape to emotions and de-potentializing threatening and tormenting figures. Through this process of abstraction, the human being seeks a point of tranquility and refuge (SILVEIRA, 1982).

Nise, as a pioneer of Analytical Psychology in Brazil, followed Jung's guidelines and began to observe in the works of her clients not only contents of personal history, filled with density, desires, disappointments and hopes, but also mythologies concerning the collective unconscious. She identified the presence of mythical themes and a collective substratum common to all men, which, in Jung's words, is the result of

frequent reversion, in schizophrenia, to archaic forms of representation, which made me first think of the existence of an unconscious not only constituted by elements originally conscious, that had been lost, but possessing a deeper layer, of universal character, structured by contents such as mythological motives of the imagination of all men (JUNG apud SILVEIRA, 1982 p. 97).

Jung considered that delusions, hallucinations, neologisms and gestures in schizophrenia are not meaningless. Intense affective charges linked to drives of the unconscious would disrupt the ego, taking possession of the conscious (JUNG, 1964). In this sense, one can see the contrast between Jung's ideas and those of Traditional Psychiatry.

Therefore, according to his point of view, the paintings of psychiatric patients are shown as tools for therapeutic, scientific and also aesthetic purposes, as these individuals show themselves as potential artists. In addition, their expressive and creative activities, in the same way that they show the functioning of the patient's psychic dynamics, may also open new perspectives of social acceptance.

Regarding clients who paint in psychiatric hospitals, Jung formulated an idea that is an invitation to reflect on the patient with the mental disorder when he says that it does not matter that its authors live in a psychiatric institution, because being immersed in the depth of the unconscious, in the portion of collective psyche, they also participate, even if unconsciously, in the psychic life of all human beings (JUNG, 1964).

Objective and research method

The objective of this work was to analyze, in the visual media production of a psychiatric patient, the manifestation of aspects of his personality through personal and/or universal themes, shared by all men, such as myths and archetypes of the collective unconscious. The aforementioned aspects were able to assist in clarification of the client's psychic dynamics.

This qualitative research paper was funded by the Foundation of Aid to Research of the State of São Paulo (Fapesp) and consisted in the analysis of paintings made by a frequent visitor to workshops held by a Community Center of a psychiatric hospital in the state of São Paulo.

The procedure included an initial phase of participative observation of the workshops held at the Community Center, from which the research's participant was selected, according to his attendance and availability. The observations were recorded in a field diary and the initial research lasted three years. However, other sporadic encounters and visits to João's house were held in order to follow up on the production of new pieces of art for the next fifteen years.

As a source of complementary data, a series of interviews were held with the participant: the initial interview followed a model called the Thematic History of Life (CALDANA, 1998), according to which, at first, the interviewee is asked to freely tell their life story; a second stage interview then investigates specific issues of interest to the researcher through semi-structured topics, which included requests to describe and comment upon the works of art.

Throughout the development of the research, both in the participative observation phase at the Community Center as well as during the interviews, when the client spoke about the paintings, the relationship established between the researcher and the participant was a focal point. In order to maintain a welcoming posture, unconditional acceptance and the non-judgment of productions, the teachings of Dr. Nise da Silveira were followed. No aesthetic evaluation was made and no psychological interpretation was transmitted to the author, as learned during an internship at the Museum Images of the Unconscious, which helped in the development of this research paper.

The analysis of the artwork can be carried out through the study of a series of images. Paintings made by the same author, if examined sequentially, reveal the repetition of motifs and the existence of a continuity in the flow of images of the unconscious (SILVEIRA, 1992), as do dreams. Particularly in schizophrenia, there is the emergence of archaic contents, which, according to Erich Fromm, translate a language that is not dead, but "possessed of their own grammar and syntax" (FROMM apud SILVEIRA, 1992, p. 94).

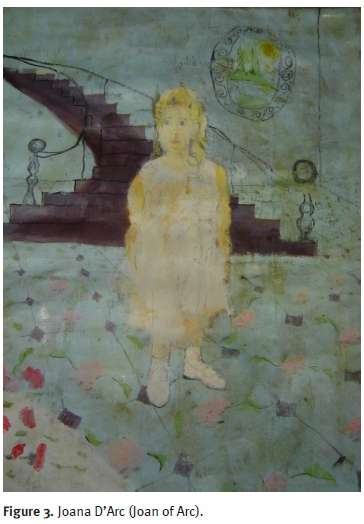

The participant painted more than fifty works throughout his life, both at the hospital and at home. For this study, 4 works were selected in chronological order of their production: 1) Desabafo (Outburst); 2) O casal e a marinha (The couple and the navy); 3) Joana D'Arc (Joan of Arc) and; 4) O céu verde (The Green Sky). The first two were painted at the workshop of the hospital's Community Center mid-2003; and the latter João painted at home, Joan of Arc in 2003 and The Green Sky in 2017. These paintings were chosen because they presented a greater representation of symbolic and archetypical contents.

The analysis of the paintings focused on their symbolic aspect. Thus, the investigation searched for meanings and the significance of the symbols present on the canvases. Following in the steps of Nise da Silveira, by analyzing the works through a series of images produced by the participant, the research sought to identify the repetition of motifs and the existence of a continuity in the flow of images of the unconscious (SILVEIRA, 1992).

The qualitative analysis of the interview and the observations aimed to identify the elements that assisted in the pursuit of meaning of the symbolic universe expressed in the paintings, considering that the recognition of the conflicts faced throughout the client's life history would be important to the analysis of his expressions.

The author of the paintings

João (fictional name), single, is 58 years old and is from the state of São Paulo. Born to a housewife and a construction worker, he is the youngest of children. He reports that he was born prematurely when his mother was seven months pregnant, "inside a ball, a sphere, which was not the placenta", that gave him "superior intelligence to others and was a warrant of God" [sic].

Of humble origin, João considers that his childhood was good and describes himself as extroverted and cheerful: he played with friends, pulled pranks at school and "messed" with the girls.

According to the participant, he repeated the first grade three times "because he was very mischievous"; the teacher failed him "despite having the grades to pass." Intelligence is constantly referenced: he was always seen as intelligent by teachers (especially by the art teacher who considered him creative, an artist); and to family and friends, his work indicated his intelligence. João said that he made paintings and sculptures that were admired by teachers and family, including the school principal, who had one of his sculptures in her office.

João said that, as an adolescent, his romantic relationships were solely platonic and idealized. He began his sex life with a prostitute and, according to him, only had relations with "ladies of the night".

He began working at 17 as an administrative assistant in a general hospital and remained in the job until he was 24, when he had his first psychotic outbreak; due to his psychiatric disorder, he was retired by disability. He shows in his medical record the diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, with delusions of religion and of greatness, as well as auditory hallucinations.

It is interesting to note that the first outbreak occurred shortly after two important events in João's life: a case of heartbreak and a case of sexual abuse. The first happened at work, where he reports that he was in love with his boss and supervisor who did not correspond to his romantic attempts. Despite the flirtation, the relationship "did not work because she was older and richer" than him, "and was the head of the workplace." He became very sad about this situation and "slept little and felt a void in his head."

Disillusioned, João had relations only with prostitutes and reports that on one occasion he was sexually abused by a transvestite when he imagined he was being intimate with a woman. This fact left João confused about his sexuality and emotionally shaken. Since then, the hospitalizations have been frequent; the participant states that he has been hospitalized more than ten times.

During this period of suffering from heartbreak and abuse, he attempted suicide by poisoning and self-harmed his chest with scissors: he wanted to "stab them into the heart." On that occasion he was hospitalized for about a month at the psychiatric hospital.

At age 38, João went through another psychiatric outbreak when he had persecutory thoughts about his father wanting to rape him, and about his father being possessed by the devil and wanting to poison his food. During this episode, João spent around twenty days without proper food intake.

Regarding his mother, the participant stated that she was a very good person, the reincarnation of Our Lady of Fatima on Earth.

At age 40, João was again hospitalized due to an outburst of aggression in which he tried to stab his brother - his caregiver and legal guardian - having confused him with a man who was invading the house. During this time, João held the belief that he was God and that he would save the world. During the period of hospitalization, he stated that he was a woman and that God wanted him like that; he became withdrawn and eventually assaulted another patient saying he was assaulting God. The participant was released a month after his entrance to the hospital.

His arrival at the Community Center of the psychiatric hospital occurred during one of his hospitalizations: the doctor discovered his relationship with the arts, especially painting, and sent him there. João is mainly dedicated to the painting workshops. It is important to note that this is the only place where João is allowed to go to alone (he does not need his brother to go along with him) and, for him, painting is "a haven, a rest, a leisure, an occupation" and even a source of small income. Currently, he has been painted more frequently at home.

In the conversations with João, two themes were of great note. The first revolves around the figure of Joan of Arc, indicating a peculiar relationship with her. He painted Joan of Arc on a canvas he made himself and kept it at home, on an easel in front of his bed, denoting its importance to him.

He stated that he fell in love with Joana after watching a movie and realized that their life stories are similar. He says that the two were raped and heard voices of God. From then on, João nurtured a platonic and idealized passion for Joan of Arc. She was the great love of his life and would be in heaven waiting for him; after his death he intends to marry her and will ask God for her hand.

The participant says she is a saint, a maiden; he says he can talk to her and get messages from her in his mind, by telepathy. In addition, she protects him, such as during an episode in which he broke his nose in a fight and went to the hospital: João did not receive care at the hospital, but after spending the night at his house, he awoke with his nose healed, saying: "I'm sure it was her who healed it."

In the interviews, João constantly commented about one of his feats, some grand invention or an exceptional power. In doing so, he always returned to the theme of his intelligence: all his inventions occurred through his very bright mind, which received telepathic messages from God.

His inventions would include: flying saucers, "faster than the speed of light," with a recipe involving plastic, rubber, wood and electricity; a rejuvenating machine, which had the goal of making him re-age to age 11 to be able to marry Joana d'Arc at 8 years old; a machine that makes transgenic foods; and another that transforms black people into white people. In addition, he states that through his mental power he manages to make an income distribution through the television.

Analysis of the paintings

If there is a high degree of shrinkage of the consciousness, often only the hands are capable of fantasy (C. G. Jung)2.

In general, the paintings are done in strong, vivid and colorful tones. The participant himself classifies his work as belonging to the impressionist style; self-taught, he learned to paint and draw through books about Monet, Renoir and Van Gogh. These characteristics also mark the four selected paintings (Desabafo, O casal e a marinha, Joana D'Arc and O céu verde), which will be analyzed below.

1. Desabafo (Outburst)

According to the participant, this work was themed after an outburst of an anguish that he was feeling and "needed to get off his chest by painting people". In this sense, one can understand that the figure represented visually from the chest upwards, in the foreground, is a representation of the painter himself and the background can represent what is happening in the author's intrapsychic world.

The background, according to João, is a theater in England, where Shakespeare's play "Romeo and Juliet" is performed. The people in front have just watched the play; all of them went alone and there were no couples.

The theater, along with the title Outburst (Desabafo), can be associated with the phenomenon of catharsis, expressed since Greek theater. According to the description of the painting and the rest of the images presented, it is necessary to think about what the feminine and masculine aspects mean to the participant-- more specifically, the relationship between man and woman and the obstacles for this meeting to occur.

The work highlights female figures, as they are in greater number and more detailed. There are two men, one with no visible arms and the other with an outstretched hand, as if waiting for something. The first, without arms, can represent the difficulty to get in touch with others; passivity; and the impossibility of action and of carrying out tasks. The second man is expressed in a smaller size, which may indicate a weakness in relation to women, who are larger and portrayed in more detail. In addition to this, one can think of a rejected man, due to his outstretched waiting hand; the woman in green in front of him has her back turned, not answering to his gesture.

Among the women, the presence of a brunette, a blonde and a redhead stands out, a recurring motif in João's paintings. In this work, of the three female images, the focal point is the central brunette figure, in a purple dress, holding a hand fan and bearing an angry expression. This image can represent the primitive, dark aspects of an aggressive and violent femininity, which involve a welcoming sense, with a challenging and authoritarian attitude that can pose a threat to the participant.

There is also a blonde woman in a long green dress, holding a purse, who, as previously stated, has her back turned to a man who expects contact with an outstretched hand: this is the feminine aspect that rejects and does not welcome the masculine.

Another female figure appears to be arriving from the right with her arm extended (as opposed to the man on the other side of the image), as a gesture of potential acceptance or even the possibility of an encounter between them.

The last female figure is the redhead, who appears represented as a teenager, with a bow on her head, a skirt at knee-level and a shawl covering her torso and arms. One can think of this figure as a passive and unwelcoming aspect of femininity, as she has no apparent arms.

According to Furth (2004), during the analysis of a visual production, one must be aware of the "obstacles" that may exist for the encounter of the represented images. In this painting, there is a man with an outstretched hand in the left corner and a woman offering a hat in the right part of the canvas. Between them, there is a certain distance and some other previously mentioned figures that may be preventing the encounter of the masculine with the feminine. Parallel to the play "Romeo and Juliet" in which the two families are obstacles, in this painting the "obstacles" would be the figure of an angry woman and the lack of resources for contact and action on the man's part, expressed by the absence of apparent arms. It is worth remembering that the participant has already attempted suicide by poison after suffering from heartbreak, which is precisely the outcome of Shakespeare's play.

In this sense, the representation of the male figure is seen through a passive and fragile light. The female figure is viewed as the negative aspect of the participant's anima, through an authoritarian, aloof and unfriendly image.

Making a parallel with João's life story, he would relate to the "armless" man who was unable to meet a woman: there were no actual meetings in his relationships, because the women, according to him, either did not correspond to his love or betrayed him. An example of this is a former boss who João was passionate about, whom he viewed in an idealized, platonic way and with whom he did not feel able to relate to, because she was rich and he was "only a poor employee". Finally, it is clear how current this theme is for the painter in the following sentence: "The theater is old, but the people are not, they're from our time" [sic]. The allusion to the age of the theater can refer to the psychological structures of João, in the sense that the architectural representation may be a parallel to his personality's structure; while the people from this age, as they are human figures, may be related to his complexes of affective tones.

2. O casal e a marinha (The couple and the navy)

This work is organized in perspective, in which a couple appears in the foreground while boats, a fisherman and buildings were painted in the background. The details of this painting appear mainly in the couple's clothing, through the hats, the suit and the long dress.

João claimed that he created this painting because he is very fond of the sea. Prominently in the left corner, he painted a couple that went for a walk on the beach. Again, the theme of masculine and feminine is in the spotlight, this time appearing through the couple, as the meeting actually takes place.

This image of the couple walking on the beach's sands conveys an idea of fulfillment of the participant's wish and fantasy. As if this couple - who is in France, according to João - was the personification of him and Joan of Arc.

Regarding the representation of the feminine and masculine, it is noticeable that the base of the two - their feet - do not appear. The man's feet appear to be hidden in the sand and the woman's are concealed by the dress. In this sense, especially in relation to the woman, it is clear that his location and sense of support are not satisfactory, conveying a "crooked" feel. Symbolically, one can think of this as a lack of psychic support or egoic structure.

The yellow presented in the theater of Desabafo (Outburst) is also here in deformed stains in the water, denoting the same unconscious structure, only more diluted. The black-haired woman resembles the brunette with the hat held out of the previous painting. Now the meeting is already taking place and there is correspondence between the two, even if rudimentary, but no rejection.

Another interesting aspect is the shape of the sea: depending on the viewing angle of the painting, one can spot a resemblance to a big fish with fins (the boats) emerging from the water. The curve of the water in the sand makes a shape similar to a mouth that is about to swallow the fisherman. The black dot, a distant boat, can represent the eye of the big fish and a red sail from a boat resembles a tongue.

The unconscious representation of a large sea fish about to catch a fisherman symbolizes the invasion of the unconscious threatening the conscious ego. Here there is a parallel to the mythical theme of the whale-dragon, which Dr. Nise da Silveira also observed in the client Olívio Fidélis, who made a canvas with the same motif (SILVEIRA, 1982). According to her, in moments when the subject is impacted by intense affections, the unconscious activates archetypal forces that can swallow the ego, constellating ravenous monsters that threaten the individual (SILVEIRA, 1992).

Regarding this, Jung in his book "The psychic energy" (JUNG, 1987) explores the theme of the whale-dragon which, according to him, portrays the principle of libido progression and regression. If the hero is in the belly of the sea monster, this portrays the individual's alienation from the outside world, a regressive movement of his libido. A parallel can be made with João's psychotic episodes, when his delusions and hallucinations become more evident and his ego is split from reality.

However, Jung reports that this night sea-crossing can also signify a dive into the inner world of the psyche. The act of dominating the monster from within can represent an effort by the individual to adapt to his inner world (JUNG, 1987). The challenge is to make this dive with some diver's equipment, as suggested by Nise, so that the subject is not swallowed by the unconscious.

3. Joana D'Arc (Joan of Arc)

This artwork is recognized by the participant as his favorite and most important one. This painting was kept on an easel at the foot of João's bed, who said that it was placed there to protect him. The work is very significant because it was the artist himself who made the canvas by nailing a bed sheet to a wooden frame and spreading several coats of glue until it reached a texture close to that of white tarp, then painted the image3. When João talks about this composition, especially in relation to the figure of Joan of Arc, the affection he has for this image is noticeable.

João states that Joan of Arc is his great love and that, as soon as he dies, he will ask for her hand to God and marry her. He even painted the face of his beloved on his pants as a way of showing his love.

In the painting, the participant says that he painted an aura around young Joan's head to indicate its elevation and illumination. This sense of enlightenment is also expressed in the white color of her clothing, which symbolically means purity and candor.

In general, the painting is well-structured and organized. It has a detailed floor, providing support and a base for the central human figure. Detailing the floor are flowers, and there is also a red flower vase on the table in the foreground. The flowers represent the presence of the feminine element. The red of the petals is a symbol of passion and expresses the participant's feeling for Joan of Arc. The picture in the background, in yellow, refers to the theater in Desabafo and also bears a sun, representing the conscious state.

The painter describes that he wanted to represent Joan of Arc descending a stairway directly from her home in the sky, as an immaculate figure who comes to meet, save and protect him. He states that he will be happy when he marries Joan and is far from Earth, the place of his suffering. The color of the stairs is purple, a symbol of spirituality, indicating that the participant's contact with Joan is sacred. Joan goes down the stairs of heaven and humanizes herself in doing so. This opens the possibility of an encounter between male and female on Earth, in real life.

In this way, Joan of Arc assumes the role of heroine in João's life, just as she historically saved and liberated France from the English. The theater of the painting Desabafo was English, and probably represents João's psychotic structure. To become free from the English would be to become free from his psychotic imprisonment. This personification of the archetype of the hero and the martyr was constellated as an attempt to rescue him from the whirlwind of threatening images of the unconscious that plagues those who have a psychotic structure.

The figure of Joan of Arc is another pole of feminine images that appeared in João's paintings. While in other works there were ladies of "the night", with seductive garments, angry and authoritarian appearances, in this one the heroine appears in an aura of illumination, protection and purity. The impression is that this archetypal image represents an aspect of the Self and the archetype of the divine child, as to João, the image of Joan of Arc helps in his organization and has an effect of the renewal of his psychic energy, promoting more motivation and creativity. From the Jungian perspective, it is through the archetypical constellation of the divine child that there is a possibility to the future change in the individual's personality, as the 'child' is a symbol for the experience of the new and works as a mediator, a cure carrier, i.e., a fixer that brings more integration (JUNG, 1976).

4. O céu verde (The green sky)

This work was painted fourteen years after the image O casal e a marinha and the similarity between the two is clear. João had no intention of re-editing the old painting and had not noticed the resemblance. This time, he says he painted a mother and son on the beach, differing from the couple in the previous painting. There is a green boat abandoned in the center of the image. One can also note the presence of a submerged sea monster that was not noticed by the painter, which reveals that there was an archetypal pictorial manifestation without influence of the ego.

One question that could be asked is whether or not the constellation of the mythical theme of the whale-dragon once again could be a harbinger of a new outbreak and alienation of the conscious. However, after visits to his home, it was noted that João was not in a pre-outbreak state, since he was painting at home and managing to get on with his life. Despite the risk, there was noticeable de-potentialization in the psyche of the author of this threatening figure in relation to the previous painting with the same motif. Here, the sea monster is not about to devour anyone.

Another aspect that draws one's attention is the presence of a mother with her child on the beach. According to the author, she is taking care of the boy and took him for a walk. An affectionate and maternal relationship can be perceived, perhaps a sign of the subject's internal resources exercising the role of self-care.

This painting is one of the most recent in the series and, in this sense, there is an observable transformation of the psychic dynamic. He has managed to live alone, to go to his doctor's appointments by himself, to prepare his meals and build a brick house with his money; a different situation from the time the researcher met him. When the researcher first met him, he lived in a precarious house with leaks and no door, a kind of shack. Thus, it is notable how João is now more organized and not so "swallowed" by forces of the unconscious, represented by the sea monster.

Final thoughts

A first comment to be proposed is that painting was, for the participant, the only therapeutic means available, in addition to medication. According to João, "painting brings peace. You paint and see what you have built and you rejoice". It is possible to perceive, through his speech and his participation in the painting workshops, how much this activity is valued by him. This resource can also help him as a way of developing his autonomy and social insertion, since João left home to go to the Community Center and interacted there with other members of several workshops.

The relationship between João and the researcher also deserves to be highlighted. During these fifteen years of contact, a link was established between the researcher and the participant. João went so far as to say that the researcher would be his "marchand", since the researcher encouraged him in the workshops and held exhibitions of his works. One of the exhibitions was held collectively with other clients of the Museum Images of the Unconscious and a work by João was even sent to Rio de Janeiro and is now a part of the museum. All these aspects, certainly, brought value to João's expressive artistic activity.

The researcher tried to put into practice the learning he acquired during his internship at the Museum of Images of the Unconscious of Rio de Janeiro, such as empathy, unconditional acceptance of the themes painted by João and, especially, the establishment of an affective bond. It was significant to follow the development of João and to note that there was a decrease on the number of psychotic episodes. A symbolic representation was the accomplishment of having a brick house, which he managed to build to improve his quality of life, in contrast to the leaking shack where he used to live during the first visit.

Focusing on the reflections referring to the images painted by João, in an attempt to clarify his psychodynamics through the symbolism present in his art production, we can highlight some points.

Faced with observations of the pictorial contents and in conjunction with the author's biographical narrative, it was noticed that there was a profound regression of his libido, through the invasion of the unconscious, in which the fragile ego succumbed to threatening forces represented by the mythical theme of the whale-dragon. When João painted the "O casal e a marinha" (The couple and the navy), he was going through a period of emotional instability that, one year later, led to a psychotic episode and to a period hospital commitment that lasted one month.

The central theme of disagreement and heartbreak was one of the factors that contributed to his illness. A correlation was noticed with some clients of the Museum Images of the Unconscious that were accompanied by Dr. Nise that also fell ill for love, as is the case of Adelina Gomes and Isaac Liberato, who were unable to live their passions and managed to portray these anxieties in their artwork. According to Lopez-Pedraza (2010), falling in love for someone may also cause a disease, a pathos feeling, which can be increasingly integrated to the relationship. In this sense, Eros would act, quoting Hillman (1984), as a "synthesizer, an agglutinant agent and mediator that reconciles two domains; builds symbols" (p. 80). However, those aspects may be harmed during psychotic states, due to an ego weakened by the suffering of some impossible love.

Just like in the song A deusa da minha rua sung by Nelson Gonsalves4 that narrates a relationship impossibility between two people, in the verse that says "she is so rich, I am so poor, I am a commoner, she is noble, it is not worth dreaming", João also identified the disparity of him being poor and his beloved rich as the cause of his love mismatch.

About the feminine element in the painter's production, the presence of two types of women emerged, one authoritarian, aloof and unfriendly; the other, on the other hand, is personified in the figure of Joan of Arc, characterized by purity and protection, related to positive aspects of his anima. It is clear that the act of painting configures a place for him to give shape to his internal dramas, in an attempt to remove threatening contents from his psyche, de-potentializing them (SILVEIRA, 1992).

The figure of Joan of Arc also has an archetypal character, and, according to its importance given by the participant and its symbolism, this image is considered as a potential regulator and organizer in the psyche of the participant. Thus, even if the individual is in psychological distress, when painting he can access internal and self-regulating healing forces.

Finally, a parallel with the current moment seems to be particularly interesting: the mythical theme of the whale-dragon that was constellated in the paintings may also reflect collective aspects that humanity is experiencing with the coronavirus pandemic, in which everyone was affected by this crisis, as if humanity itself was swallowed straight into the dark belly of the sea monster. ■

References

AMARANTE, P. Manicômio e loucura no final do século e do milênio. In: FERNANDES, M. I. A. (Org.). Fim de século: ainda manicômios? São Paulo, SP: Cabral, 1999. p. 47-56. [ Links ]

BASTOS, J. F. Cícero Dias/Ismael Nery: a poética do surreal. 1993. Tese (Doutorado em Artes Plásticas) - Escola de Comunicações e Artes, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, 1993. [ Links ]

CALDANA, R. H. L. Ser criança no início do século: alguns retratos e suas lições. 1998. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia) - Centro de Educação e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, 1998. [ Links ]

CAPRA, F. O ponto de mutação. São Paulo, SP: Cultrix, 1988. [ Links ]

FURTH, G. M. O mundo secreto dos desenhos: uma abordagem junguiana da cura pela arte. São Paulo, SP: Paulus, 2004. [ Links ]

HILLMAN, J. O mito da análise. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Paz e Terra, 1984. [ Links ]

HIRSZMAN, L. (Dir.). Imagens do inconsciente. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Embrafilme, 1986. (Canal do YouTube Victor Farjado). Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-uN1lsWFjM&t=68s>. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

______. Chegando ao inconsciente. In: JUNG, C. G. (Org.). O homem e seus símbolos. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Nova Fronteira, 1964. p. 18-103. [ Links ]

______. Energia psíquica. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 1987. [ Links ]

______. Os arquétipos e o inconsciente coletivo. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 1976. [ Links ]

LOPEZ-PEDRAZA, R. Sobre eros e psiquê. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2010. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, N. Imagens do inconsciente. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Alhambra, 1982. [ Links ]

______. Mundo das imagens. São Paulo, SP: Ática, 1992. [ Links ]

Received on: 03/22/2021 1

Phrase said by Nise da Silveira in the documentary trilogy Imagens do Inconsciente

(HIRSZMAN, 1986).

Revised on: 16/05/2021

2 Available on: http://www.ccms.saude.gov.br/nisedasilveira/encontro-com-jung.php.

Accessed on: march 21, 2021.

3 Unfortunately, the canvas

became rotten, having grown moldy after being hit by rainwater.

4 Available from: https://www.letras.mus.br/nelson-goncalves/47649/.

Accessed in: March 15th, 2021.

texto en

texto en