Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Junguiana

versão On-line ISSN 2595-1297

Junguiana vol.40 no.1 São Paulo jan./jun. 2022

Cultural complex in the metropolis in times of COVID-19

Cyntia Helena Ravena Pinheiro

Psychologist in jungian approach, graduated at Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, specialist in jungian clinic at UNIP. Master and Doctor in science at USP. Trainee Analyst from SBPA. e-mail: cypinheiro.psi@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The reflection proposed by this article arises from the need to understand the reasons that led the metropolis of São Paulo to succumb to the adversities of the pandemic. The author establishes a weaving that interweaves georeferenced maps of Covid-19, the city's urbanity, behaviors, feelings, memories and the ancestral roots of São Paulo and Brazil, which offer the raw material for identifying the cultural complexes involved in this current drama. ■

Keywords: COVID-19, cultural complex, São Paulo, analytical psychology.

Introduction

The pandemic announced since the late 1990s, after the 1997 avian flu, materialized in 2020 with COVID-19. Snacken et al. (1999) alerted to the constant imminence of a pandemic due to the variants of influenza viruses, to the necessary development of an intervention strategy suitable for each country and especially to the fact that the next pandemic would find most of the world unprepared. Fifteen years ago, Ujvari (2004) drew attention to a virus that had been causing respiratory infections in man: the coronavirus (SARS-CoV), but he was not heard, and the emergence of SARS-CoV2 took place, as predicted (CARMO et al., 2020).

Our relationship with the urban environment has been challenged by the new coronavirus. The risk of contamination, social isolation, lack of scientific knowledge about the behavior of the virus, controversial discussions regarding alternatives for the treatment of people with symptoms caused by SARS-CoV-2, as well as the mental health of those who lived together with its imminence or its consequences, have been importante challenges.

Haunted by the coronavirus, I resorted to reading the book "Pandemias: humanity at risk", by Stefan Ujvari (2011), seeking to understand the variables that influence our behavior in the face of current challenges, facing the pandemic. I also dialogued with the Cultural Complex and other Jungian contemporary perspectives on the psyche and the society by Thomas Singer, Samuel Kimbles (2004) and some colleagues. Jung's works constitute the foundations of those proposed by this article.

Challenges of modernity and the coronavirus

In "The spiritual problem of modern man", Jung (2013) presents his lecture at the Congress of the League of Intellectual Collaboration, held in Prague, in October 1928, in which he points to the challenge we face in living in the present, as this requires the awareness of our existence as a human being at this moment. At the same time, there is the pain of awareness of the past, of the inheritance inherent in human history that constitutes us psychically. Jung brings the reflection that can be made about the paradox between the benefits offered by scientific, technological and technical advances and their catastrophic effects. Thus, with modern consciousness, the human psyche lives in a deep insecurity, a shaken faith in ourselves as a civilization. From this perspective, the current pandemic confronts us in terms of our historical roots, our individual and collective psyche. Jung emphasizes that something of our psyche is not individual, but related to people, the collectivity, the humanity.

In this text, Jung warns of the importance of paying attention to the possibility of incurring in distortions and false conclusions when we start from the perspective of personal psychology in the description of an idea or cultural problem, which can generate serious consequences. This is the challenge of the elaborations and proposals in that article. He also invites to a reflection with respect of the West critical situation and the dangers of arrogance in the face of other cultures, such as those of African and indigenous peoples.

Starting from the Jungian premise that evil comes largely from man's own unconsciousness is both frightening and comforting, as the enemy in us may seem more accessible to be fought. The Jungian conception of the dynamics of the unconscious is expanded, recognizing that we are all part of a single psyche: anima mundi. The intrinsic relationship between the outermost and the innermost, between the anima mundi and the self, was mentioned by Jung as early as 1912, in Symbols of Transformation (JUNG, 1912/1986, p. 550). Thus, the anima mundi involves simultaneously the most intimate part of man and the world (JUNG, 2014a, p. 554).

As early as 1928, in the period between the two world wars, Jung (2013) draws the parallel between the shaking of the world and the shaking of our consciousness. He weaves the net that connects reality inside and outside, the conscious and the unconscious, West and East, science, rationalism and spirituality, body and spirit, aiming to value the experience of totality, the coniunctio of these polarities.

At the present time, the reflection is on the psychic problems of man before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, inspired by Jung's thinking in the face of the psychic shock of modern man resulting from the realization of his fragility and the shadow that manifested itself in his ability to destruction, denounced by the atrocities of the great world wars. He suggests that, recognizing that there are no answers in the present, they lie in the "abyss of the future". However, actions in the present can predispose that future. Luigi Zoja (2000), in "History of Arrogance", confronts us and instigates an answer to this abyss of the future.

I turn to some "ingredients" for this elaboration in the purification fire, lit by the pandemic, this civilizing mark in the city of São Paulo: what cultural complexes would be operating in the metropolis and how would they be related to the numbers of COVID-19? After all, what makes us so vulnerable to this virus, despite advances in science and technology and being in the largest Brazilian city?

From the perspective of the cultural complex

Boechat (2018) refers to the conditions that led to increasingly in-depth studies of the interactions between individual and culture, from the Industrial Revolution. He considers that Jung was one of the thinkers who in the 20th century focused on social issues and that it was up to post-Jungians to continue studies and understand these relationships between the individual and culture. The perspective of the cultural unconscious and cultural complexes emerges. The choice of the cultural complex perspective as a theoretical framework aimed to explore deeper beliefs and emotions, in group and individual contexts and representations, in images, emotions, patterns and practices. The cultural complex concerns the conflicts that are observed in a nation or collectivity. It originates at the beginning of the organization of a culture and develops throughout its history. Through the activity of these complexes belonging to a cultural context as a whole, the individual has a feeling of belonging to a specific group, with a specific identity (KIMBLES, 2004).

The notion of the cultural complex was first proposed by Joseph Henderson in a letter to Jung in December 1947. Although he did not develop this concept further, he contributed to the foundations and description of the cultural unconscious, building on Jung's proposal for the collective unconscious. Henderson conceptualized that this unconscious instance would be closer to the ego consciousness than to the collective unconscious (SINGER, KAPLINSKY, 2019). These authors consider that the notion of cultural complex presupposes the uniqueness of different cultures and their specific complexes. In the same way that complexes act on a personal, individual level, cultural ones can possess the group and make it think and act in a non-rational, non-politically correct way, even though the latter may itself be a cultural complex.

Cultural complexes are mixed with personal ones. These affect each other mutually, express repetitive behaviors and high emotional and affective charge, are resistant to consciousness, create cores of ancestral memories. Both present autonomous functioning and correlation with archetypal nucleus. Cultural complexes have bipolar behavior: one part identifies itself with the unconscious cultural complex and the other projects itself onto the group or one of its members, adopting somatic languages, gestures and body postures shared by the group. Cultural identity can be contaminated by positive aspects, but also by the negative aspects of cultural complexes. Like affective complexes, cultural complexes can radiate, influence others with whom they have an affinity, generating effects that are often destructive to culture. Individuals whose personal complexes have an affinity with the cultural ones existing in the society to which they belong, suffer the tensions of the synergy between these psychic instances.

Singer (2018) considers as a criterion for identifying a cultural complex to investigate a series of questions regarding the various types of mental activities that are recruited when a cultural complex is triggered. Based on these precepts of Singer, I sought to identify the images, memories, behaviors, feelings, and thoughts observed in the São Paulo context that made it possible to infer which cultural complexes would be present there.

Images: São Paulo, mosaic city, harlequin

São Paulo was historically constituted by the multiplicity of cultural contributions, resulting from the presence of immigrants from different origins, European, Asian, African, Latin. Barcellos (2010) discusses the contradictions, difficulties, and potential of this cultural mosaic of people, dreams and constructions that characterize the city of São Paulo, which he called "Cidade Arlequim". The allusion to the figure of the harlequin in Italian comedy, with his multicolored costume, a trickster, is present in the work of the poet, novelist, and modernist essayist from São Paulo Mário de Andrade, in Pauliceia Desvairada, 1922. Barcellos emphasizes that the city is, at the same time, the place and image of the soul and that anima and polis can be perceived first by the heart experiences. He exposes the contradictory, paradoxical experiences lived in the love-hate relationship with our city. It is both mother and lover, it deceives and delivers, ennobles and diminishes those who seek it.

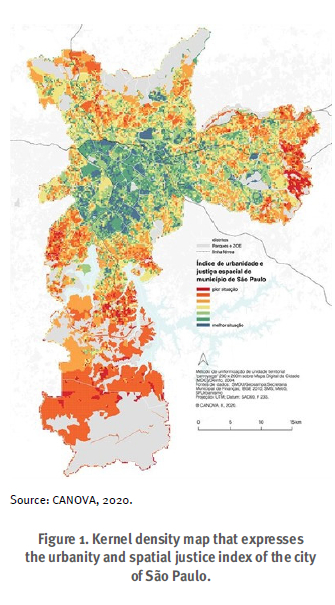

Inspired by the author's metaphor, I recognize the strong emotional experience of learning over the mosaics that will be presented in the maps that follow, in search of answers to the questions of this research. As much as Mário de Andrade and Gustavo Barcellos, I have an affective relationship with my city, and I seek to understand the dynamics of people's relationships with the city and urban environmental issues (PINHEIRO, 2018). The maps express some relevant data from the city and from COVID-19 in this context, as triggers for reflections on the psychic mechanisms underlying the behavior of citizens in this metropolis. The city of São Paulo is the largest in Brazil, the fourth most populous in the world and is considered one of the 33 megacities, according to a United Nations report (2018). Its population is of about 12 million inhabitants, who live in an unequal city, according to the 2018 São Paulo Social Responsibility Index (ASSEMBLEIA LEGISLATIVA DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO, 2018), as it is a city with high levels of poorly distributed wealth, associated with unsatisfactory social indicators (low longevity and/or schooling) (FUNDAÇÃO SISTEMA ESTADUAL DE ANÁLISE DE DADOS, 2018). Other data from the municipality can be analyzed from the images chosen for our reflection.

The first map, Figure 1, provides an image of the urbanity and spatial justice index in the city of São Paulo (CANOVA, 2020), from which we can establish correlations with data referring to the population most affected by COVID-19. Canova highlights the parallel between inequality, lower incidence of public services and consequent higher prevalence of diseases, also associated with environmental factors. Her work reveals the importance of cartography as a tool for exploring the geographic determinants of health and the territorialization of events that cause and spread diseases. The analysis of data generated by georeferenced information systems, such as the one we see in Figure 2, also offers subsidies for the planning of actions aimed at facing the current pandemic.

Urbanity reveals the realization of the interactional character of the city. The greater the urbanity, the greater the integration of social groups, as well as access to urban resources, making the city more productive and creative in the whole of social life. Thus, the smaller, more compact, dense, and diverse the city, the more they are in line with urbanity. Canova (2020) uses criteria that also include the analysis of indicators pointed out in reports from the United Nations Program for Urban Settlements (UN-Habitat), to deal with the problems of cities. The map in Figure 1, resulting from the matrix analysis of weighted indicators, contemplates fundamental issues of urbanity and spatial justice, at the municipal, regional and local scales. It reveals that the worst situation is found in the most peripheral areas of the city, while the best is observed in the most central region. Canova (2020) emphasizes that, like most large cities in the world, urban planning in São Paulo emerged a posteriori from intense occupation and varied and disorderly growth, without a previous urban planning program. It mentions how incompatible it was and still is the adoption of imported models and linked much more to the economic model of production.

The areas with the worst urbanity and spatial justice situation largely coincide with those with the highest number of blacks and browns, as shown in the maps in Figures 1 and 2. The historical roots of hygienist policies, social exclusion and structural racism justify the fact of the majority of the black or brown population to occupy the "banners of the city". Goes et al. (2020) show the correlation between racial inequalities and the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil and mention the same situation in the United States of America.

The geography of COVID-19 in the city of São Paulo was also the subject of investigation by researchers from LabCidade at Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo - FAUUSP (MARINO et al., 2021) and the Observatório das Metrópoles (PASTERNAK et al., 2020). In the first months of the pandemic, they verified the movement of the virus towards the most peripheral areas of the city of São Paulo, with precarious urban infrastructure, equipment and housing, especially slums and tenements, which favored the worsening of the contagion situation, hospitalization and deaths in greater numbers in these regions.

It can be inferred, by superimposing the maps in Figures 1 and 3, the correlation between the lowest rates of urbanity and spatial justice, the absence of urban infrastructure, and the most expressive numbers of deaths per 10,000 inhabitants caused by COVID-19. 19 between March 2020 and March 2021. They reveal the disparities with which São Paulo citizens live, the social vulnerability, the inefficiency of public policies throughout history, as well as the disparities that citizens faed during the pandemic.

The map in Figure 4 shows the strong correlation between the distribution of public transport travel origins in the city of São Paulo and the areas of the city with the highest number of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) hospitalizations at the beginning of the pandemic. They were especially located in the outskirts of the city, from which essential health and supply service workers, domestic workers, and public transport users came from, to guarantee services to the population.

According to Instituto Polis (2021) and Labcidade from FAUUSP (MARINO et al., 2021), the immunization process reinforced inequalities. This finding is reached by correlating the maps in Figures 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6. It is verified that immunization with two doses until May 17, 2021 did not prioritize the most vulnerable areas, considering that the lowest percentages of coverage of the vaccination occurred in those with the highest number of deaths from COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021. According to data prior to that period, they were characterized by younger age at death and lower urban infrastructure.

The maps pointed to this reality and made it possible to adopt measures, but the criterion based on existing international epidemiological data prevailed, which indicated a higher prevalence of deaths among the elderly and those with comorbidities, and the limited number of doses available of the vaccine. The naturalization of this condition of vulnerability and the lack of agility and efficiency of the public power favored the worsening of the situation with the spread of the disease. The analysis of the data expressed by these images, by these mosaic maps, associated with the understanding of the historical and cultural aspects of the city, can help in the identification of the cultural complexes that act in the collective and individual psyche of the citizens of São Paulo.

Cultural complexes: memory and identity

Cultural complexes emerge to consciousness, coming from the cultural unconscious, continuously interacting with the instances of the personal and collective unconscious. Singer and Kaplinsky (2019, p. 58) cite Henderson's (1990) definition of the cultural unconscious as an area of historical memory, which lies between the collective unconscious and the manifest pattern of culture. One can then attribute to it a characteristic that is both conscious and unconscious, including the collective unconscious.

It is related to cultural memory, a living, dynamic process. It is important to remember that the process of rooting, of building the identity of a community is linked to both individual and collective memory in the culture. As much as personal complexes, cultural ones tend to be repetitive, autonomous, resistant to consciousness and identify experiences that reaffirm their historically constructed worldview.

Dias and Gambini (1999) consider it important to place our history in the context of a global psyche. Analyzing the European psychic topography of the 16th century, we can attest that the New World represented a psychic escape valve for the shadow of Europe: "the pressure of the shadow is what created the southern hemisphere" full of sin. Below the equator, impulsiveness incompatible with the European Catholic world, which saw itself superior to other peoples, was allowed. The psychological projections that fell on indigenous peoples referred to representations of the European unconscious. They generated enchantment, but they could not be accepted, they were forbidden, sinful from the Judeo-Christian perspective of the colonizers, which is why they were automatically projected onto the other. In other words, "we were born as scapegoats for a story that is not ours, we were born to compensate the other" (DIAS, GAMBINI, 1999, p. 55). We are a nation with an atrophied ego, without compassion, in which social inequalities are tolerated. The authors emphasize that the way out lies in raising awareness, assuming our shadow, otherwise we will continue to project it on indigenous peoples, blacks, and women.

The proto-Brazilian was born, then, from the colonizer and from a mother reduced only to her biological function and to servile work, psychically prevented from integrating her son into her ancestry. Restricted to a womb, arms, and lap, without protagonism, the native Brazilian mother was prevented from transmitting to her mestizo child mythology, religion, conscience, imagination, attitude towards life, which may explain the feeling of non-belonging, of non-identity. European civilization was experiencing the Inquisition at that historic moment of discoveries and repressed the principle of the feminine, of which indigenous women and nature were living representations. The child born to this woman with the white conqueror had no place in society, he was an outcast. As a result of this historical process, there is a lack of polarity necessary for the process of psychic integration in Brazilians, an immaturity of the ego due to the atrophy of the female side, the anima. The Brazilian feminine is impoverished, reduced to the object of desire or, more recently, reproduces the masculine, patriarchal model for being in the world. The authors emphasize that only the principle of the feminine, of women and men, could restore aborted alchemy, the process of transformation, the coniunctio that was left unfulfilled. What remains to emerge in Brazil is the archetype of the Great Mother, who watches over her children, feeds them, and has compassion for their suffering. Social inequality in the country maintains this exclusion framework (DIAS, GAMBINI, 1999).

Not only indigenous peoples were depositaries of the colonizer's white culture shadow. They were followed by a large contingent of men and women brought in the holds of slaveships, sold as slaves in colonial Brazil. Fuentes (2014) presents, from the perspective of analytical psychology, the perspective of the African Brazilian soul, which seeks to be integrated, recognized. It exposes the silencing, marginalization, poverty, invisibility, racial prejudice to which the contingent of African peoples in Brazil was subjected. The violence of exclusion to which the author refers exposes Afro-descendants to the inaccessibility of citizens' rights and the impossibility of constituting their identity and fulfilling themselves as a person. Ramos (2011) exposes the cultural complex and the elaboration of the trauma of slavery in Brazil. She compares the relationship with the ancestry of undergraduates residing in the cities of Salvador and São Paulo. The research reveals that the former are unaware of their ancestral roots, while the latter, of predominantly European descent, are aware of their ancestral family origin. Afro-descendants residing in São Paulo mention how skin color is a determining factor for feelings of inferiority and discrimination.

Dias and Gambini (1999) assert that there is a perverse mechanism to prevent the "pieces" of the Brazilian soul from being integrated into the whole. There is still an exclusion mandate, a Brazilian psychic debt. The recognition of the guilt of white society towards indigenous and black societies is essential, so that we can become aware of our identity.

It is understood, then, from what has already been exposed, that the cultural complex of the excluded is present in us Brazilians, who, jettisoned from our ancestral roots, wander aimlessly, seeking Africa or Europe as a cradle, not Brazil. Jung (2014b), in his 1925 seminars, mentioned this complex, referring to the English who, having lived for a period in Africa, could not be considered equal by Africans, nor by their English compatriots, since they had been influenced by the former, either by language, style or habits. In the same way, we are then, literally, a society of excluded people and perhaps therein lies the reason why we have naturalized exclusion in our society.

The reading of "Tristes Trópicos", by Lévi-Strauss, published in 1955, inspires us with the ethnographic contribution, to confront us with our São Paulo shadow:

A feeling of unreality, as if all that were not a city, but a simulacrum of buildings built hastily to serve a film shoot or a theatrical performance. [...] São Paulo was as proud as Chicago of its Loop: a commercial area formed by the intersection of Direita, São Bento and 15 de Novembro streets, streets filled with signs where a crowd of merchants and employees who, in their dark clothes, proclaimed their fidelity to European or North American values [...] (2016, p.104-5).

His words refer to the formation of Brazilian identity and national memory based on the appreciation of the foreigner, this gaze always turned outwards, towards the influences coming from the so-called "more civilized" countries. Boechat (2018) asserts the urgency of diving into the roots, into the traditional values of Brazilianness, so that we can find our genuine collective identity.

According to Gambini (DIAS, GAMBINI, 1999), the Brazilian myth exists, it is always present in each of us, unconscious, but we are out of step with it, we are not interested in the search for a collective identity. To recognize the myth, we would need to get in touch with our roots, with the path where we came from. In this way, the non-recognition of the myth of origin, of the hero or heroine in the Brazilian collective psyche, important in the constitution of national identity, generates in us Brazilians a feeling of non-belonging, of rejection of the things of the country as ours and, therefore, that demand care (RAMOS, 2004). This lack stems from the rupture of culture, social relations and, as already mentioned, the representations of the indigenous soul in Brazilian society by the action of the colonizer, under the "debris of a psychic genocide", as analyzed by Gambini (1994).

But, even if our conscience does not recognize this indigenous soul, it inhabits us, it constitutes one of the strata of the psyche, in which the geological layers reveal the planetary history. This analogy was made by Jung (2014b), in the Seminars on Analytical Psychology (1925), that the layers of the psyche speak of the overlap, from the surface to the deepest layers: individuals, families, clans, nations, large groups of nations, primate ancestors, animal ancestors in general. These different psychic instances with which we live reveal themselves, constellate in our behavior and denounce the shadow or shadows of Brazilian culture, its cultural complexes. They result in inferiority and excluded complexes, which can be seen in the behavior of ci tizens and in public policies in the metropolis of São Paulo.

Behaviors: citizenship and public policies

Observing the city of São Paulo, one can notice signs of the absence of the citizen and the action of its political representatives when we are faced with the poor quality of the waters of its rivers and streams, with the streets sprinkled with garbage, with the mutilated trees or their absence. Our libido has long since turned its back on the city and turned towards us, narcissistic subjects, who no longer interact face to face, nor do we know the meaning of citizenship. Sociologist Laymert Garcia dos Santos (2002) exposes his reflections: São Paulo is no longer a city, not because it was promoted to metropolis, but because the spirit of the city no longer inhabits its residents.

His spirit has faded and now everything begins to show the signs of disintegration and decomposition. But nobody cares what has already happened, is happening or is about to happen. The city's agony is a side effect that no one sees or wants to see (p. 116).

There is a paradoxical opposition between nature and progress in the capitalist world and it is no different in Brazil. The myth of the Edenic foundation of Brazil, prodigal in natural wealth, has contributed to its devaluation, as these are still considered today as inferior to those produced with industrial technology. Like the things of nature, we are, as Brazilians, inferior; the more ecological, the more natural, the more inferior. The intellectual qualities and productions, the advances in technology produced in Brazil tend not to be recognized by the nation. (RAMOS, 2004).

The inferiority complex of Brazilians, the lack of trust in institutions, in governments, generate the absence of the population in the spaces of dialogue and construction of public policies and management, as asserts DaMatta (1997, p. 19): "strayed, we are almost always mistreated by the so-called 'authorities' and we have no peace or voice".

Feelings: do I belong or not?

The monuments and symbols of a city reveal its personality, show the "face" of the city to the world around it and represent the more or less ideal image of itself, as stated by Stein (2010). They say not only about its cultural identity, its most cherished values, its self-awareness, but also what the city wants to project for its inhabitants in the present and in the future. However, as much as they display the persona, they also display their shadow. Murray Stein emphasizes that within and behind the persona are hints of what the city consciously represents, as well as what it may unconsciously want to reveal but cannot do so directly or officially. Ramos (2012) discusses the symbols of force representation in the city of São Paulo, expressed by the coat-of-arms: "Non ducor, duco" (I am not led, I lead), by its animal symbol: brown jaguar, symbol of power, being the strongest and biggest feline in the State of São Paulo. He also mentions the monument to the Bandeirantes, referring to "paulistas" as a race of giants, who never submit. It is a granite sculpture by Victor Brecheret, inaugurated in 1953, as part of the celebrations of the fourth centenary in the city of São Paulo. It represents the exploration expeditions that left the city for the interior of the country. There are two men on horseback, a Portuguese colonizer who heads the mission and an indigenous man as a guide. Behind them follows a group of indigenous, black, Portuguese and mestizo (mamelucos) people, pulling a canoe used by explorers on their expeditions (RAMOS, 2012, p. 57).

Then, the persona of São Paulo seems to be a people that does not submit. The pride expressed in the monument to the Bandeirantes is accompanied by the shadow, a devastating silence, oppression, the domination of indigenous peoples and nature. Dias and Gambini (1999) emphasize the phallic character of the endeavor of discoveries, of the colonization process, in which, deprived of the qualities of the feminine, of eros, the value of the other is not recognized. The inequality generated in the process of colonization and slavery of indigenous and black peoples reverberates, like a great earthquake, even today in Brazilian society and that is felt in the foundations of São Paulo. There is in the city of São Paulo a large contingent of citizens who have migrated from different Brazilian states, who may have the same feeling of rivalry among São Paulo residents that Ramos (2012) refers to, and may contribute to the feeling of non-belonging, reinforcing the Augé (2012) idea of "non-place" which characterizes the general behavior of the population of this metropolis.

Scandiucci (2014) and Wahba (2012) analyze the problems of life in the contemporary city, through pixação and graffiti, as symbolic representatives of the complexity of behavior and the contradictions of the human soul, a possibility for young people from the outskirts of the metropolis to claim their right space in the heart of the city. The authors explore aspects of the cultural complex related to trauma, discrimination, oppression, and feelings of inferiority. They see these interventions as manifestations of the shadow of the group and the cultural complex of exclusion, inferiority, related to it.

Cultural mosaic and cultural complex of the excluded

From the analyses carried out on the mosaic maps of the city of São Paulo and the reflections already discussed regarding the cultural complexes that are present, we are faced with the contradiction, with the paradox of our times: the archetypal fantasy of globalization with inclusion revealed itself as a process exclusion of the majority for the benefit of the few, as emphasized by Boechat (2018, p. 70). And São Paulo represents this reality: an unequal city. However, as Campbell (1990) warns, in our current time, the alternative to the situation of civilization is no longer thinking about the city, but about the planet:

And the only myth that's going to be worth thinking about in the immediate future is one that is talking about the planet, not the city, not these people, but the planet and everybody on it. This is my fundamental idea of the myth to come. And it will deal with exactly what all the myths have dealt with - the maturation of the individual, from dependence to adulthood, then to maturity, and then to death; and then with the question of how to relate to this society and how to relate this society to the world of nature and the cosmos. That's what myths have always been talking about, and that's what the new myth will have to talk about. But he will speak of planetary society. As long as this is going on, nothing will happen (CAMPBELL, 1990, p. 46).

As early as 1931, in an interview with the New York Sun, Jung envisioned the need to rethink this planetary society:

We are waking up a little to the filling that something is wrong in the world, that our modern prejudice of overestimating the importance of the intellect and the conscious mind might be false. We want simplicity. We are suffering, in our cities, from a need for simple things. We would like to see our great... terminals deserted, the streets deserted, a great peace descend upon us (MCGUIRE, HULL, 1982, p. 49).

In March 2020 we witnessed the city as described: empty. And we could observe the clear sky of São Paulo because of the reduction of atmospheric emissions at the beginning of the quarantine, in March 2020 (ROLNIK, 2020), as we can see in Figure 7.

Boechat (2018) considers it important to note the close connection between psychological phenomena and those of nature, emphasizing how much Jung, in many moments in his work, resorted to the processes of nature to illustrate psychic processes, understanding that man does not exist separately of Mother Gaia.

What the metropolis can learn from the coronavirus

Are we at a turning point, the metanoia of humanity, as suggested by Fellows (2019), of which the city of São Paulo is a part? Considering the cultural complexes active in the metropolis, a mosaic representation of the Brazilian people, its still immature society, the lack of identification with its roots and ancestry, it can be inferred that, regarding the development of the group ego, we are still in a stage much earlier than the inflection point of the development curve as a city, as well as a Nation. Fellows mentions chapter XVI of OC volume 8/2 "the stages of human life", comparing the present stage of humanity to metanoia (JUNG, 2013, §773). I argue that we would still be in the previous phase. We would be in the adult phase of humanity, considering that it is only in this phase that we can have doubts about ourselves (JUNG, 2013, §760). Or are we still in the youth of humanity, conscious only of the ego, satisfying our craving for pleasure and mastery? (JUNG, 2013, §764)

At this moment, the pandemic generated by SARS-Cov-2 makes us realize the Umbra Mundi, to which Murray Stein (2020) refers to. The shadow of the world has revealed our own shadow, whether collective as a country, state, or city, or individually, represented by social inequalities, problems of urbanity, incompetence of public policies. As Brazilians, we live with the cultural complexes of colonialism, the indigenous holocaust, slavery, and corruption, to which Boechat (2018) referred, and which are the precursors of inferiority and excluded complexes.

Recognizing the cultural complexes active in the population of the metropolis, as psychologists and citizens, the challenge of acting in the face of the complex of the excluded, inferiority and arrogance is immense. This task involves the relationship that is established between the individual trauma, ours, and that of our analysands, and the collective trauma associated with the aforementioned Brazilian cultural complexes. Kalsched (2021) explores the perspective of the intersection of personal traumas with the collective generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This current collective traumatic experience has resuspended personal and collective traumas that lay in the sediments of the depths of the psyche. The "mosaic" maps presented reveal a fragmented collective psyche, which partially deals with its reality, as observed in the dissociative defenses in trauma. We are, as a nation, a child victim of an early relational trauma, daughter of a colonizing father and an indigenous mother, soulless bodies. This dialogue with Gadotti (2020), in line with Jung, regarding the reality we confront in the pandemic and the relationship between the anima-anima mundi is essential to facing exclusion. The author, adopting Jung's perspective, considers the anima linked to the matriarchal dynamics, and states that as such it acts in the perspective of Eros, as a power of inclusion and alterity, side by side with Logos. The soul without Eros suffers and gets sick, under the strict domination of capital and power, as we see in a city like São Paulo. The pandemic denounced the structural terrain of São Paulo at a disadvantage, leading to greater suffering and death, especially in areas with less urbanity and spatial justice. It opened even more the wounds of the city, and confronted us to find ways to change our current urban status, urgently! ■

References

ASSEMBLÉIA LEGISLATIVA DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO - ALESP. IPRS índice paulista de responsabilidade social. São Paulo, 2018. Disponível em: <https://www.al.sp.gov.br/documentacao/indicadores-e-diagnosticos/>. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

AUGÉ, M. Não lugares: introdução a uma antropologia da supermodernidade. Campinas: Papirus, 2012. [ Links ]

BARCELLOS, G. São Paulo: harlequin city. In: SINGER, T. Psyche & the city: a soul's guide to the modern metropolis. New Orleans: Spring, 2010. p. 85-98. [ Links ]

BOECHAT, W. Complexo cultural e brasilidade. In: OLIVEIRA, H. (Org.). Desvelando a alma brasileira: psicologia junguiana e raízes culturais. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2018. p. 68-87 [ Links ]

CAMPBELL, J. O poder do mito. São Paulo: Palas Athena, 1990. [ Links ]

CANOVA, K. Urbanidade e justiça espacial na cidade de São Paulo: metodologia de análise e subsídio para tomada de decisão no planejamento urbano. 325fl. Tese (doutorado em Geografia Humana) - Departamento de Geografia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo,. São Paulo, 2020. [ Links ]

CARMO, R. L. et al. População, ambiente e a Covid-19: o monstro dentro de nossas casas. Temáticas, Campinas, v. 28, n. 55, p. 314-41, fev./jun. 2020. https://doi.org/10.20396/tematicas.v28i55.14179 [ Links ]

DaMATTA, R. A casa & a rua: espaço, cidadania, mulher e morte no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1997. [ Links ]

DIAS, L.; GAMBINI, R. Outros 500: uma conversa sobre a alma brasileira. São Paulo: Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Comercial, 1999. [ Links ]

FELLOWS, A. Gaia, psyche and deep ecology. New York: Routledge, 2019. [ Links ]

FUENTES, L. A. Tornar-se o que se é no sentido da filosofia ubuntu africana e o sentido para a individuação na e da cultura brasileira. In: BOECHAT, W. (Org.). A alma brasileira: luzes e sombra. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014. p. 171-93. [ Links ]

FUNDAÇÃO SISTEMA ESTADUAL DE ANÁLISE DE DADOS - SEADE. IPRS índice paulista de responsabilidade Social, 2018. São Paulo, 2018. Disponível em: <http://www.iprs.seade.gov.br/>. Acesso em:13 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

GADOTTI, C. M. Viveremos em um mundo mais anímico após a pandemia? Junguiana, São Paulo, v. 38, n. 2, p. 9-22, 2020. [ Links ]

GAMBINI, R. Uma breve reflexão sobre o outro. Psicologia USP, São Paulo, v. 5, n. 1-2, p. 335-9, 1994. [ Links ]

GOES, E. F.; RAMOS, D. O.; FERREIRA, A. J. F. Desigualdades raciais em saúde e a pandemia da Covid-19. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 18, n. 3, p. 1-7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-7746-sol00278 [ Links ]

INSTITUTO POLIS. Abordagem territorial e desigualdades raciais na vacinação contra Covid-19. São Paulo, 2021. Disponível em: <https://polis.org.br/estudos/territorio-raca-e-vacinacao/>. Acesso em: 20 jan. 2022. [ Links ]

JUNG, C. G. O problema psíquico do homem moderno. In: JUNG, C. G. Civilização em transição. 6. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2013. p. 84-106. [ Links ]

_______. Os arquétipos e o inconsciente coletivo. 11. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014a. [ Links ]

_______. Seminários sobre psicologia analítica (1925). Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014b. [ Links ]

KALSCHED, D. Intersections of personal vs. collective trauma during the Covid-19 pandemic: the hijacking of human imagination. Journal of Analytical Psychology, London, v. 66, n. 3, p. 443-62, jun. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12697 [ Links ]

KIMBLES, S. L. A cultural complex operating in the overlap of clinical and cultural space. In: SINGER, T.; KIMBLES, S. L. The cultural complex: contemporary junguian perspectives on psyche and society. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2004. p. 199-211. [ Links ]

LÉVI-STRAUSS, C. Tristes trópicos. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016. [ Links ]

MARINO, A. et al. Prioridade da vacinação negligencia a geografia da Covid-19 em São Paulo. Labcidade, 26 maio 2021. Disponível em: <http://www.labcidade.fau.usp.br/prioridade-na-vacinacao-negligencia-a-geografia-da-covid-19-em-sao-paulo/>. Acesso em: 2 dez 2021. [ Links ]

MCGUIRE, W.; HULL, R. F. C. (Coord.) C. G. JUNG: entrevistas e encontros. São Paulo: Cultrix, 1982. [ Links ]

PASTERNAK, S.; D'OTTAVIANO, C.; BARBON, A. L. Mortalidade por Covid-19 em São Paulo: caminho rumo à periferia. Observatório das Metrópoles, 16 jul. 2020. Disponível em: <https://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/mortalidade-por-covid-19-em-sao-paulo-ainda-rumo-a-periferia-do-municipio/>. Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

PINHEIRO, C. H. R. As entranhas da minha cidade: da geologia à psicologia arquetítica, um diálogo com Hillman a partir da leitura de "Cidade & Alma". In: ALCANTARA, A. et al. (Orgs.). Atas do colóquio cidade & alma: perspectivas. São Paulo: Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo, 2018. p. 115-24. Disponível em: <https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/46703/1/CIDADEEALMA2018.pdf>. Acesso em: 28 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

RAMOS, D. G. Cultural complex and the elaboration of trauma from slavery. São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudo Junguianos, 2011. Disponível em: <https://www5.pucsp.br/jung/ingles/publications/24_05_2011_cultural_complex.html>. Acesso em: 28 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

______. Non Ducor, Duco, I am not led, I lead. In: AMEZAGA, P. et al. (Eds). Listening to Latin America: exploring cultural complexes in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay and Venezuela. New Orleans: Spring, 2012. p. 51-74. [ Links ]

______. Corruption: symptom of a cultural complex in Brazil? In: SINGER, T.; KIMBLES, S. L. The cultural complex: contemporary junguian perspectives on psyche and society. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2004. p. 102-23. [ Links ]

SANTOS, L. G. São Paulo não é mais uma cidade. In: PALLAMIN, V. M.; LUDERMANN, M. (Org). Cidade e cultura: esfera pública e transformação urbana. São Paulo: Liberdade, 2002. p. 111-8. [ Links ]

SCANDIUCCI, G. Um muro para a alma: a cidade de São Paulo e suas pichações à luz da psicologia arquetípica. 2014. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia) - Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, 2014. [ Links ]

SINGER, T. The cultural complex theory: scientific and mythopoetic ways of knowing. In: CAMBRAY, J; SAWIN, L. Research in analytical psychology: applications from scientific, historical, and cross-cultural research. New York: Routledge, 2018. p. 110-25. [ Links ]

SINGER, T.; KAPLINSKY, C. Complexos culturais em análise. In: STEIN, M. (Ed.). Psicanálise junguiana: trabalhando no espírito de C.G. Jung. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2019. p. 54-75. [ Links ]

SINGER, T.; KIMBLES, S. L. The cultural complex: contemporary junguian perspectives on psyche and society. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2004. [ Links ]

SNACKEN, R. et al. The next influenza pandemic: lessons from Hong Kong, 1997. Emerging Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, v. 5, n. 2, p. 195-203, mar./abr. 1999. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0502.990202 [ Links ]

STEIN, M. A world shadow: Covid-19. Asheville: Chiron, 2020. Disponível em: <https://chironpublications.com/a-world-shadow-covid-19/>. Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

STEIN, M. Searching for soul & Jung in Zurich: a psychological essay. In: SINGER, T. Psyche and the city: a soul's guide to the modern metropolis. New Orleans: Spring, 2010. p.13-32. [ Links ]

UJVARI, S. C. Meio ambiente & epidemias. São Paulo: Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Comercial, 2004. [ Links ]

______. Pandemias: a humanidade em risco. São Paulo: Contexto, 2011. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS - UN. The world's cities in 2018: data booklet. New York, 2019. Disponível em: <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3799524>. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2021 [ Links ]

WAHBA, L. L. São Paulo and the cultural complexes of the city: seeing through graffiti. In: AMEZAGA, P. et al. (Eds). Listening to Latin America: exploring cultural complexes in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay and Venezuela. New Orleans: Spring, 2012. p. 75-107. [ Links ]

ZOJA, L. História da arrogância: psicologia e limites do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo: Axis Mundi, 2000. [ Links ]

Received: 02/10/2022

Revised: 06/05/2022

texto em

texto em