Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282

Rev. bras. crescimento desenvolv. hum. vol.21 no.3 São Paulo 2011

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The perception of shelter care educators: their work and the institutionalized child

Celina Maria Colino MagalhãesI; Lígia Negrão CostaII; Lília Iêda Chaves CavalcanteIII

IProfessora

Dra do Programa de Pós-graduação em Teoria e Pesquisa do

Comportamento, UFPA. Rua Augusto Corrêa,01 - Guamá. CEP 66075-110.

Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa CNPq

IITerapeuta Ocupacional, mestranda do Programa de Pós-graduação

em Teoria e Pesquisa do Comportamento, UFPA,Bolsista CAPES. Av. Dalva, nº

537. Marambaia. CEP 66615-850

IIIProfessora Dra do Programa de Pós-graduação

em Teoria e Pesquisa do Comportamento, UFPA. Rua Padre Eutíquio,nº

1922, apto 2300. Batista Campos - CEP 66033-000

ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to study the perception of shelter care educators regarding the work performed by them as well as their effect on the institutionalized children under their care. Questionnaires were administered to 102 educators working in the largest shelter care facility in Belem from the year 2004 to 2006. The results indicated that in the educator's view, in general service was satisfactory, and whereas basic physical needs were being met, provisions for affective and intellectual growth were not adequate. In particular, children in these facilities had little privacy, nor were they provided sufficient individual attention. Furthermore, the educator's work appeared to exert minimal influence on the children's cognitive and emotional development. Such information may be useful for formulating more effective pedagogical policies, emphasizing a more integrated link between child care and education.

Key words: children; child care; shelter care educators; child psychological care.

INTRODUCTION

Parental behavior is known for the care, protection and education of children through a set of actions characterized by beliefs and attitudes that show the parents perspective about taking care and raising their children. The way parents take care of their children and strategies used for infantile care, interactions maintained, and actions are in consonance with ideas (beliefs, attitudes, inferences, knowledge, opinions, values and goals) and parental feelings (affection, emotion) in relation to infantile socialization and development1.

According to several authors2,3 beliefs have influence on the parental care and behavior, possibly exerting several effects over the children's behavior and the infantile development. Nonetheless, although parental practices are associated to their beliefs there is no direct cause and effect relation between them. Beliefs are built in social interactions and they interfere on how people behave, what may lead to an inconsistency between what it is thought and what it is done.2

Harkness and Super3 suggested the concept of developmental niche as a tool to analyze the cultural structure of the infantile development. This model is composed of a system and by three subsystems interconnected that coordinate themselves through time and permeates the human developmental pathways such as: the physical and social environment, which correspond to the child's home structure and the social-familiar organization the child is part of; the care practices and child's education, associated to raising and educational practices culturally determined; and the parents ethno-theories (caretakers psychology), which are cultural models that represent parents' beliefs and values about children and family as well as conceptions on how children should be raised3.

Caretakers' psychology in a non-familiar context is a relatively new research field and it calls attention of those who investigate the primary socialization processes and the developmental pathways in childhood. Publications on this subject are very rare when compared to the clear current interest on how parents raise children4. Although there is a reduced number of research dedicated to this matter it's already possible to find investigations of shelter care educators psychology.

Even though the expression shelter care educator seems new to the academic and social means it acts in accordance with the constitution of the pioneers shelters for children and adolescents of Brazil, in conformity to the principles established by the Child and Adolescent Statute (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente - ECA)6. The use of this term is both antique and current, for representing the image of professionals responsible for a specific kind of foster care, the institutionalized one, responsible for children without parental care or those who maintain a fragile bond with parents or any person responsible for them.

It can be noticed that the shelter educator's impressions about the children attended in this institutions bring back images and conceptions which carry marks by a long history of charity assistance to misfortunate children, since the Roda dos Expostos (Wheel oh the Exposed) time; attention given to poor and abandoned under aged in welfare institutions; and in the last decades by temporary admittance as a measure of especial protection due to their condition of subjects of rights7,8.

Thus, even with all the efforts to disseminate the ethical and political principles of CAS5 the image of childhood at risk still remains as a threat against society, and somehow it represents a problem to people around these children. Even though situations of commotion for children who stay in these institutions for a long time are common, the image society creates about the psychosocial conditions of these children is still full of misconceptions, fear, and prejudice. In other words, who these children are and how they live, from the point of view of the caretakers, is an issue for debate nowadays. Perhaps the set of answers obtained in this debate will help clarifying some aspects that underlie the institutional care of children in risky situation, as well as provide subsidies for the creation of a political-pedagogical project that takes into consideration how the educators comprehend the history and the development of children in institutionalized care.

In these terms, the shelter educators understanding of who the children in these institutions are should be in accordance to a pool of historically associated beliefs of their psychosocial conditions. These beliefs are here understood as ideas that for long have belonged to the social imaginary and make reference to old public nursery and orphanage7,8,9. They also illustrate the antique and current literature about the deprivation of maternal or parental care10,11, as well as they support the discourse about the severe social and emotional vulnerability of the confined children12.

In reference to this issue, some researches4,13,14 reveal that studies on the nursery's educators beliefs about aspects related to the human development can be useful for the implementation of policies and programs of infantile education more sensible and adjusted to the conditions in which these professionals perform their jobs. A similar reasoning can be applied to redeem the importance of the knowledge that includes the perceptions of shelter educators about the limitations and the opportunities imposed by their work, in a sense of promoting the children's welfare and development.

For this matter, it is understood to be necessary to properly know the conditions in which the educators carry out their work in the institution and their opinion about the development of children that are under direct or indirect influence of their practices of care and education. Therefore, the present study aims at analyzing the shelter educators' perception about the work developed by them and about the children in institutionalized care.

METHODS

Participants

Took part of this study 102 educators from a shelter institution from 2004 to 2006. These participants corresponded to 83.61% of all employees in this occupation. All members of the sample are women (100%), most are younger than 35 years old (61.76%), and have children (54.91%). More than a half of the educators (55.86%) attends or have already finished college in one of these specialty: pedagogy (53.84%), teaching degree (26.96%), social service (7.69%), nutrition (3.84%), psychology (3.84%) and, sociology (3.84%).

In the body of the text the expression educators younger or older than 30 will be used when age is considered relevant to the analysis. This age range was chosen due to the greater distribution in two groups: from 20 to 30 years old (45.10%), and from 31 up (43.14%) included in this group are those older than 40 (11.76%). It is called attention to the fact that younger educators are also those with shorter experience in the institution, a year or less (42.15%)

Environment

This study was performed in an institution for children in a vulnerable situation aging from 0 to 6 years old. Shelter is considered as a high complexity service that is part of the Social Assistance System (Sistema Único de Assistência Social - SUAS). The biggest and oldest shelter for children is located in Belém's metropolitan region, in the north region of Brazil. This institution currently attends an average of 50 children including infants; however this number frequently reaches 70 to 80 boys and girls.

The educators and other professionals in this organization are selected through public contests for being managed directly by Pará State Government as part of Secretary of State and Social Development (Secretaria de Estado de Desenvolvimento e Assistência Social - SEDES)

Instruments and materials

Ongari and Molina's questionnaire was used with some adaptations to the specific context of the shelter. Some questions were added regarding the role of educators in shelters and the specificities of such infantile care.

This questionnaire contains open and closed questions about the educators' socio-demographic characteristics and their personal, professional, and organizational lives. Most questions present variables which have a nominal statistic measure. Nonetheless, it also brings questions that require other types of analysis as ordinal and interval. With the use of a Likert scale (1 to 5 points - from 'completely disagree' to 'completely agree') it was sought to measure the level of concordance between the interviewed and the literature discussing the psychosocial condition of an enclosed child, in addition to accessing ideas and beliefs related to this topic that are still present in the current society.

Procedure

It was mandatory to obtain a court authorization to perform the survey for the fact that the organization is designated to guard children apart from their family living. As a second step the project was sent to the Ethic Committee of Researches with Human Beings (CEP/MMT) from Nucleus of Tropical Medicine at Pará Federal University, which approved the study proposal with no objections or alterations. (Protocol nº 062/2004 - CEP/MMT, signed in 09/08/2004).

The data collection started with the application of the questionnaire to the shelter's educators by the researcher. These interviews were performed during the educators' working schedule. The questions were asked orally and the answers were written down by the researcher.

The collected data were compiled and analyzed through the Excel software, version 2007. The statistical analysis was made by calculating frequency and percentage and figures were chosen to demonstrate the results through simple and accumulated frequency.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Educator's perception about children in institutionalized care.

The results of the investigated variables describe traits of perception the educators have about the modality of infantile care and its effects on the development of children under their care in these institutions. This means to notice the objective and subjective conditions in which the infantile care practices take place, and to have elements to think about the child's niche of development in these institutions3.

The roll of obtained perceptions was organized into six axis: 1) socio-familiar conditions; 2) attention to essential needs; 3) characteristics of the living environment; 4) interaction and relationship with adults; 5) interaction and relationship with children; 6) effects of institutionalization.

The following results show the educators' position on the concordance with ideas and beliefs historically associated to the psychosocial conditions of the institutionalized children. By investigating the concordance percentage of educators with subjects about the socio-familiar condition of the children it was noticed that practically half of the educators agreed to the statement that children sent to shelters have families (50.98%). According to them most times children have a family reference and keep some connection with the family, receiving sporadically visits from them at the shelter. This perception is more common for the educators older than 30, probably because they had the opportunity to witness several children going back to their families as soon as their more urgent needs were met.

In fact, contrary to what seems concrete to the social imaginary many children have been pushed away from their home and deprived of living together with their parents, even though having family reference and their location is known5,16.

In the north region almost 89% of children and adolescents in shelter have family against 86.7% in all the country16. The numbers from this region also indicate that 58.9% of sheltered children and teenagers have families and keep contact with parents or close relatives. This should be, theoretically, one instrument to facilitate the process of returning to the family living.

Educators, both older and younger than 30, don't have the idea that the sheltered children necessarily come from a family with a poor background. In their opinion poverty cannot be taken as the reason alone to explain the amount of children sent to provisory care. They believe in the existence of thousands of poor children being well taken care by their biological parents staying away from risky situations as domestic violence and abandonment. Nonetheless, recent studies on the profile of children and adolescents in care institutions in Brazil indicate that poverty persists as a reason (many times the only or most relevant one) for depriving them of living with the family16.

More than half of educators, no matter the age, agree that the children were institutionalized in a very important moment of their development (87.26%). This result might reflect the fact that there is a large dissemination of information about the children development and the importance of living with the family for the primary socialization process and the attachment formation. The access to such information may not occur only in professional training but also through the media (e.g. TV, internet) and other means that are willing to show how harmful the separation or loss of parents and families figures can be even if temporary.17.18

In what concerns the opportunity to fulfill the children's essential needs by the institution, most educators consider the care with feeding, sleeping, hygiene, and physical safety are satisfactorily provided (90.20%). Although more than 70% believe it's impossible for the children to be intellectually stimulated in the shelter environment.

The data above are considered revealing for showing how distant it is the materialization of a conception of institutionalized care which assures the needs of children in physical, emotional, and social vulnerability will be fully met, as established by Technical Orientations to Shelters for Children and Adolescents, written by the Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger19. Once more prevails the idea that infantile institutions are supposed to fully zeal for the child, however, according to educators, they guarantee physical survival, not its development as a social and intellectual being.

The discussion on the pseudo-primacy of education over care as indicated some studies is here again presented. In the past the organization for children care, especially daily nursery, were seen as public or communitarian work designed to hold children that for some reason the parents couldn't do it properly13,14,15,20,21. Nowadays it is an increasing concern that those organizations need to provide both physical and educational care in the same degree. Those actions need to be concomitant while maintaining the children's biggest interest: to have conditions to develop their human potentialities22.

Regarding the educators' perception about the shelter environmental characteristics, two thirds agree that the children have little freedom to make choices about practical things in this context (72.55%), or cannot enjoy of personal space or privacy (66.67%) as demonstrated in Figure 1.

However, the perception of environmental characteristics typical to nursery or closed institutions seems more common to the educators older than 30 years. The hypothesis here proposed is that the maturity and the experience in dealing with childhood provide these professionals with a greater sensitivity to recognize what is private and personal for structuring the individual's personality23. When discussed the differences between the group care offered in institution and residences in comparison to individual care in foster family23, some studies verified that children who received individual care in foster homes, even if had early institutionalization, presented better performance in some measured abilities23. Different from those who have received group care, despite of being in residential institution that resembles the characteristics of a home or children who lived in traditional nursery. These data show how decisive it is the way the children with lack of parental care are treated in their immediate environment, during and after their staying in the institution.

It could be noticed that a very small percentage of educators (3.92%) conceive that children are mistreated inside shelters. Most part of tutors believes this is not a correct statement. They argue that children might not be receiving all the necessary attention for their emotional and physical welfare, but they are not mistreated. They (educators) declare having no record of physical punishment by employees or any kind of profiting from the children's work, or yet negligence with health and security as frequently seems to happen when living with family of origin.

Regarding the interaction dynamics between children and adults inside the institution, when analyzing the concordance level, it is clear that most educators consider the children not to be having sufficient individual attention in the shelter. The rationale is that the tutors are so concerned in accomplishing tasks, including the care of children in different ages and psychological conditions on a daily basis, they consequently have no time to treat every child as a single being, respected in its idiosyncrasies, when clothing after shower, feeding in the cafeteria, and motivating it to take part in some activities24.

In these moments, contradicting what have been affirmed by theorist of human development 3,25 many educators put the value of this knowledge on second place and how this could facilitate living with each other and in addition boost what they have special in their subjectivity.

Some authors in preview studies15,20,21 affirmed that in infantile shelter organizations the activities are repetitive but not in the same way for each child. In these terms the authors call attention for the repetition of activities but not of children who are single beings and experience activities in a single way and as should be recognized as such.

The subjects interviewed (almost 90%) share the belief that sheltered children keep unstable and short relationship with adults who are mostly educators, but also cleaners, technicians, visitors, volunteers, and the like.

In the past it was taken for granted the idea that children raised in a group environment and away from home would keep numerous social and affective relationship that would lead to impairments to their improvement13,14,15,20,21. Nonetheless, recent studies are questioning this conception demonstrating that children raised in a collective environment as day care centers learn how to take advantages from these multiple interactions and experiences, and also that affective bonds can be numerous without bringing any distress to their emotional growth.

In shelter institutions the relationship between children and educators or other adults have mostly not only a complementary nature, as it happens in pre-schools and day care center although full time. In the institutional environment this relationship becomes more complex for the children who in most cases have neither built reference figures in the living with the family nor in the interaction with caretakers from foster contexts26,27.

Another aspect that must be emphasized regards the fact that the largest concordance percentage of educators relies on the constant dispute of children to have the educator' attention (92.16%). One of the possible reasons why this occurs is the greater number of children in comparison to adults; an excessive number of children in such facilities may impair the dispensed attention especially to infants.

Analyzing the educators' opinion about how the child-child interaction is established and the particularities of this social bond, it is demonstrated that 89.21% consider true the statement that pair groups exert great influence on the child's behavior. In regular conditions it is believed that a group can influence how people think and act. In relation to children, especially those who live in institutions, the power to dictate behaviors and attitudes is a consequence of the learning by imitation in this age, of the physical proximity, that facilitate group cohesion, and of the person's social adjustment strategies, being at risk of giving in to the pressures of the environment.

The results indicate that 38.23% of the educators consider it possible and common for children to create stable and durable relationship with others at the same age. This share of mentors agree that the long period of time spent with same aged children inside the institution can lead to the formation of emotional bonds characterized by friendship and the attachment feeling between preferred peers.

Several authors13,14,15,20,21 assume to be beneficial for children to have their early socialization associated to living in an institution, essentially day care centers and schools, due to the great range of company and interplay peers in such institutes. However, in what concerns the daily living with children at the same age range in institutions some studies have showed that the child-child interaction is not only important but necessary to their complete welfare. In the absence of adults with who they can establish strong and lasting emotional bonds, the sheltered children tend to seek company, comfort, and emotional security among their similar 5,9,26.

Another set of categories to be discussed refers to the effects of institutionalization known by educators as elements that are present in the shelter's universe. Figure 2 shows the percentage of agreement of educators concerning the sequelae of a childhood spent away from home. It shows that there is no agreement in what concerns to such consequences of sheltering, not even when related to a positive side of sheltering as the idea that an istitutionalized child has a greater capacity of adapting easily to odd and new situations.

The educators recognize that it's been common the presence of children behaving aggressively towards adults and peers (71.57%). Likewise, 47.06% emphasize the fact that institutionalization makes children live on a daily basis with people and experiences quite different from those they used to live in their home or neighborhood. From most educators' point of view this contingencies guide the children to a more flexible behavior, regarding changes in the environment and the people around them.

Although specialists9,17,18 have recognized its existence, stress produced by the necessity to adjust to the reality in the shelter comes from the fact that the institutionalized children have to deal with strange situations that bring about feelings of insecurity, difficult to be pushed away. The child thus has to experience the so called total separation (night and day), for being, in most cases, taken to a shelter without any previous preparation. In general, they leave an environment literally familiar to a, at first sight, hostile and strange. In this unknown place they usually have difficulties to build an emotional reference, as people who represent a safety net for situations of risk, anguish, anger and rage. Moreover, they frequently have to take part of unpleasant situations making mandatory some undesired experiences like forced meals, shower and sleep. Not mentioning some playful activities that not always are motivated by educators or other professionals responsible for the daily care.

The educators' perceptions about the work with institutionalized children and its influence over their development

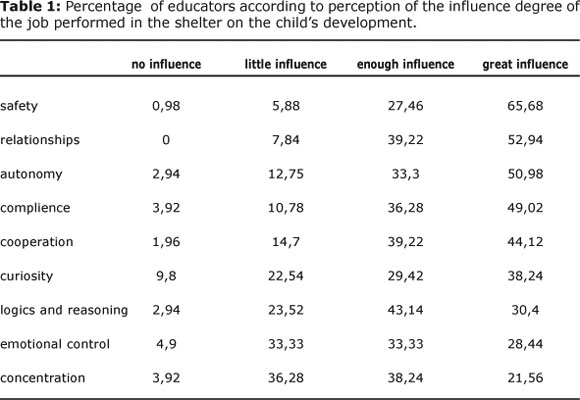

The perception about the work that is done on a daily basis in the shelter differs on the level of influence that it has over the development of children in institutionalized care. Table 1 shows the educators' viewpoint about the influence level their work have on the acquisition of some infantile abilities and competences.

Educators consider themselves having great influence over the children's behavior and some crucial aspects of their psychological improvement, especially in relation to feeling secure (65.68%), being capable of relating to others (52.94%), being self-governing (50.98%), just to mention the most cited categories. The sum of percentage corresponding to great influence and enough influence represents more than two thirds of the educators, which means to say that it is very positive the assessment they make about their work to the social, emotional, and cognitive development of the sheltered children.

Concerning the possibility of the educator's work influence on the children's autonomy in different circumstances, the children are usually stimulated to have control over its own body and vital functions (go to the bathroom, feeding, showering) and to participate on activities that enhance their motor, cognitive, and playful skills14.

Educators, on their turn, understand they have few or no influence on awakening the children's curiosity to explore the environment (32.34%), the development of logic and reasoning competence (32.46%), and how to deal with emotions (38.23%). However, about controlling the emotions, educators state that this improved ability doesn't depend only on the work established by them, but on the fact that the child has been away from its home and emotionally impaired because of this situation.

In relation to the ability to control emotions, tutors see it as a hard task even for adults, and even harder for children emotionally distressed. In this context, they learn that children are surprised by the need of a rigid social adjustment to the rules imposed by the life in the institution and its own dynamics for being very different from the family environment or from other children's facilities25. The exercise of controlling basic emotions such as anger and fear in situations unfamiliar to the children is not an easy task and demands a great preparation and assurance from the educator.

The aspects of the development with the lowest power of influence from educators would perhaps involve the acquisition of certain cognitive abilities, probably because, as they like to emphasize, the chances are minimum to perform a pedagogical work in the organization that aims at teaching knowledge and values defined by society. Educators consider themselves having little interference on this aspect of the children's development for associating it almost exclusively to pedagogical activities, which usually have little participation of educators in the organization and conduction of such activities.

Results show, yet, that only 16.66% consider their work to have little (1.36%) or no (14.7%) influence on the infants' gaining of social skills that are expressed as empathy and care of one child to another. Actually, the educators understand that this responsibility to stimulate the children to be willing to help their peers shouldn't be only theirs, but there is no doubt that due to circumstances, these professionals have a main role on the children's early socialization process.

Literature reveals that the educator's job can lead children to cooperate in different ways such as: helping in situations with a higher degree of difficulty; helping a colleague at risky or conflicting situations; sharing objects or food demonstrating esteem towards peers.28

In addition, institutions that receive children, especially residential ones, can stimulate them to help other with tasks and cooperate among themselves and with the employees. This kind of attitude coming from educators can contribute to prevent traumatic effects brought about by the early and long stay in asylum institutions.11

Along with the results presented here it was sought to emphasize the discussion about the educator's psychology in a shelter context, which includes ideas and beliefs about the psychosocial condition of the child and the influence of the work done in the institution for the infantile development.

Investigating the literature it was identified that the caretaker's role for the children development, mainly in what concerns to its conceptions, beliefs and ideas, have been broadly discussed. This recent search reflects the contributions brought by Harkness and Super3 in regard to motivate the sciences of human development to expand its area to ideas, convictions, values and expectancies which translate how the primary caretakers from different social and cultural contexts consider the child's potentiality. Nonetheless, despite the increasing interest the number of researches which have as study subject professional caretakers, their psychology and practices still are incipient.

In this study the use of a questionnaire permitted to know the profile of educators responsible for children in a shelter, as well as their perception about the psychosocial condition of the institutionalized children and the implications of the work performed in the shelter for the infantile development.

The survey data revealed that the educators, on its majority, share the opinion that sheltered children receive satisfying treatment from the institution as feeding, sleeping, hygiene, and security, but affective and intellectual matters remained unattended. These results reiterate the idea that the care provided in the shelter is related solely to the child's physical survival rather than its development as a social and intellectual being.

One interesting finding refers to the fact that educators consider the institutionalized child to live in an environment which doesn't favor the freedom to make choices about practical things or even with no right to enjoy personal space and privacy, not receiving in the shelter an individualized attention. This is a matter which deserves emphasis, as it is believed that values and beliefs shared by educators about infantile development have influence on their behavior and practices, besides affecting their interactions with the children.

Moreover, educators corroborate the idea that children maintain in the shelter unstable and brief relationship with adults, even though educators are constantly giving attention to the children. The tutors consider, yet, existing a strong influence of peer group over the child's behavior and only one third of them might create bonds.

In what concerns to their job in the institution educators believe to have little influence on the children's cognitive and emotional development, transferring this issue to pedagogical activities, showing that the dichotomy between taking care and educating is still present in the educators' point of view. This fact confirms the belief that reviewing the conceptions of children and their development is the most important step to face this problem.

Data suggest the need of further investment on the initial formation and ongoing training of educators, such measures could make the difference in the children's care. Technical orientation for sheltering children and adolescents19 reiterate the idea that educators must be fully capacitated do perform their role with independence and to be recognized as authority figures for the child. They must also have permanent support, orientation, and time to share ideas, experiences and anguishes from their job, seeking a joint construction of strategies to face challenges. These measures become necessary on account that the educators' beliefs and practices influence the children's development and their behavior patterns. From the educators' point of view the manner they interact and see the children day-by-day affect on decisive aspects on their developmental pathway.

New studies are necessary both to continue the same path of investigation presented in this study or yet to approach propositions of different experiences that can provide new interpretations to the issues discussed. Further investigation could take a closer look on issues that were only briefly or not discussed here, such as connecting the characteristics of the social and physical environment from the shelter to the care practices. It could also be checked the possible relationship between the educators' life history and their conceptions about infantile development and care practices.

Finally, it's accentuated the existence of many aspects that should be reconsidered or modified inside a shelter and the absence of perfect institutions which need no improvement. For that matter, it is also emphasized the necessity of a political-pedagogical project which is capable of improving this reality and take into consideration the educators' beliefs about the children development and their work in the shelter.

REFERENCES

1. Goodnow JJ. Parents' ideas, actions and feelings: models and methods from developmental and social psychology. Child Dev. 1988; 59(1): 286-320. [ Links ]

2. Bandeira TT. Investimento e crenças parentais. In: Seidl-de-Moura ML, Mendes DM, Pessoa LF, organizadores. Interação Social e Desenvolvimento. Curitiba, CRV; 2009. p. 39-56. [ Links ]

3. Harkness S, Super CM. Cross cultural reasearch in child development: a sample of the sate of the art. Dev Psychol. 1992; 28(1): 622 625. [ Links ]

4. Melchiori LB, Biasoli Alves ZM. Crenças de educadores de creche sobre temperamento e desenvolvimento de bebês. Psic.: Teor e Pesq. 2001; 17(1): 285 292. [ Links ]

5. Cavalcante LI. Ecologia do cuidado: interações entre a criança, o ambiente, os adultos e seus pares em instituição de Abrigo. [Tese]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2008. 510 p. Doutorado em Teoria e Pesquisa do Comportamento. [ Links ]

6. Brasil. Lei n. 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. [acesso em 8 jul. 2009]. Brasília, 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil/LEIS/L8069.htm> [ Links ].

7. Berger MV, Gracino, ER. Aspectos históricos e educacionais dos abrigos de crianças e adolescentes: a formação do educador e o acompanhamento dos abrigados. Rev Histedbr On-line. 2005; 18 (1), 170-185. [ Links ]

8. Rizzinni I, Rizzinni I. A institucionalização de crianças no Brasil: percurso histórico e desafios do presente. São Paulo: Loyola; 2004. [ Links ]

9. Freud A, Burlinghan D. Meninos sem lar. Rio de Janeiro: Fundo de Cultura; 1960. [ Links ]

10. Siqueira AC, Betts MK, Dell'Aglio DD (2006) A rede de apoio social e afetivo de adolescentes institucionalizados no sul do Brasil. Interam J Psychol.. 2006; 40(2): 149-158. [ Links ]

11. Wolff PH, Fesseha G. The orphans of Eritrea: a five-years a follow-up study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999; 40(1): 1231-1237. [ Links ]

12. Santana JP, Doninelli TM, Frosi RV, Koller, SH. As instituições de atendimento a jovens em situação de rua segundo a abordagem ecologica do desenvolvimento humano. In: Koller SH, organizador. Ecologia do desenvolovimento: pesquisa e intervenção no Brasil. São Paulo, Casa do Psicólogo; 2004. p. 189-192. [ Links ]

13. Cerisa AB. A construção da identidade dos profissionais na educação infantil: entre o feminino e o profissional. [Tese]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 1996. 212p. Doutorado em Educação. [ Links ]

14. Veríssimo MD. O olhar de trabalhadoras de creches sobre o cuidado da criança. [Tese]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2001. 200p. Doutorado em Enfermagem. [ Links ]

15. Ongari B, Molina P. A educadora de creche: construindo suas identidades. Ortale FL, Moreira IP, tradutores. São Paulo, Cortez; 2003. [ Links ]

16. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Levantamento nacional de abrigos para crianças e adolescentes da rede SAC. [acesso em 06 abr. 2008]. Brasília; 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.ipea.gov.br> [ Links ].

17. Beckett C, Maughan B, Ruter M, Castle J, Colvert E, Goothues C, et al. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist in to early adolescence? from the English and Romanian Adoptees Study. Child Dev., 2006; 77(1), 696-711. [ Links ]

18. Zeanah HC, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Smyke AT, Marshall P, Parker SW, Koga S. Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavior development: the bucharest early intervention project. Dev Psychopathol. 2003; 15(1): 885-907. [ Links ]

19. Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. Orientações técnicas: serviços de acolhimento para crianças e adolescentes. Brasília: 2009. [ Links ]

20. Bondioli, A. O tempo no cotidiano infantil: perspectivas de pesquisa e estudo de casos. Ortale, FL, Moreira, IP, Tradutores. São Paulo: Cortez; 2004. [ Links ]

21. Gandini L, Edwards C. Bambini: a abordagem italiana à educação infantil. Burguño DA, tradutor. Porto Alegre, Artmed; 2002. [ Links ]

22. Tizard B, Rees J. A comparasion of the effects of adoption, restoration to the natural mother, and continued institutionalization on the cognitive development of four-year-old children. Child Dev. 1974; 45(1): 92-99. [ Links ]

23. Roy P, Rutter M, Pickles A. Institutional care: risk from family background a patern of rearing? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000; 41(1): 139-149. [ Links ]

24. Santos MF, Bastos AC. Padrões de interação entre adolescentes e educadores num espaço institucional: ressignificando trejetórias de risco. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2002; 15(1): 24-52. [ Links ]

25. Bronfenbrenner U. A ecologia do desenvolvimento humano: experimentos naturais e planejados. Veronese, MA, tradutor. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2005. [ Links ]

26. Alexandre D, Vieira M. Relação de apego entre crianças institucionalizadas que vivem em situação de abrigo. Psicol. estud. 2004; 9(1), 207-17. [ Links ]

27. Nogueira PC. A criança em situação de abrigamento: reparação ou re-abandono. [Dissertação]. Distrito Federal: Universidade de Brasília; 2004. 160p. Mestrado em Psicologia Clínica. [ Links ]

28. Kallioupuska. Grouping of children's helping behavior. Psychol Rep. 1992; 71 (1): 747-753. [ Links ]

Manuscript submitted

Feb 06 2011, accepted for publication Aug 22 2011. Trabalho realizado

no Espaço de Acolhimento Provisório Infantil (EAPI), vinculado

à Secretaria de Estado de Assistênciae Desenvolvimento Social (SEDES)

do Governo do Estado do Pará. Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

liliaccavalcante@gmail.com

Baseado na Tese de Doutorado: Cavalcante, LIC. Ecologia do Cuidado: interações

entre a criança, o ambiente, osadultos e seus pares em instituições

de abrigo. 2008. Programa de Pós-graduação em Teoria e

Pesquisa doComportamento, Universidade Federal do Pará. Orientadora:

Celina Maria Colino Magalhães.

texto em

texto em