Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Journal of Human Growth and Development

Print version ISSN 0104-1282

Rev. bras. crescimento desenvolv. hum. vol.24 no.2 São Paulo 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Social representation of the hospital ludic: look of the child

Naidhia Alves Soares FerreiraI; Joana D'arc EsmeraldoIII; Marcia de Toledo BlakeI; Jennifer Yohanna Ferreira de Lima AntãoIV; Rodrigo Daminello RaimundoI; Luiz Carlos de AbreuI, II

ILaboratório de Delineamento de Estudos e Escrita Científica. Departamento de Saúde da Coletividade. Disciplina de Metodologia Científica. Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP. Brasil

IIDepartamento de Saúde Materno-infantil. Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo

IIICurso de Enfermagem, Faculdade de Juazeiro do Norte, Juazeiro do Norte, CE. Brasil

IVEnfermeira especialista em Saúde da Família pela Faculdade de Juazeiro do Norte, Juazeiro do Norte, CE. Brasil

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Play has become an object of study in various sectors of society, as it is viewed as an innate, spontaneous activity that is critical for a child's physical, social, emotional and cognitive development, which facilitates communication, socialisation and adaptation to environments and people. During hospitalisation, children feel vulnerable as they have to cope with strange carers, invasive and painful procedures. Barriers to their regular activities tend to make the situation worse.

OBJECTIVES: To describe the child's view of his/her playfulness in the hospital environment and investigate the social representation of a hospital playroom for children exposed to the story-drawing technique.

METHODS: This qualitative exploratory research used story-drawing as a tool for data collection with a sample of 12 children aged 6 to 11 years, while they were hospitalised. Data analysis was supported by a literature review and direct observation, which allowed the researchers to draw relationships between theory, the research hypotheses and the data collected.

FINDINGS: The children's construction and representation of playfulness while in hospital was directly related to the playroom, since most of them reported not conceiving of the possibility to play in bed or elsewhere in the hospital. Soon the playroom was further viewed as a place for socialising and recovering from illness as they approximated this environment to their reality in an attempt to make it a closest-as-possible representation of their homes. It was observed that play changed the children's preconceived ideas of the hospital, as they began to view the playroom as an environment in which they felt able to play and consequently well. Their story-drawings contextualised symbolically their current hospitalisation situation and became a scaffolding tool for their emotional well-being.

CONCLUSIONS: The playroom can effectively aid hospitalised children to cope better with the new situation and support the restoration of their health. Play is an emotionally protective factor for children during hospitalisation. Although in Brazil it is now mandatory for health institutions to have a playroom with paediatric care, this breakthrough policy is still challenging for some institutions with respect to being staffed with engaged health professionals and establishing routine procedures.

Key words: play, child health, hospitalisation, social representations.

INTRODUCTION

Play has become the focus of study in several fields of research, viewed as a spon-taneous and innate activity which is inherent to human development. However, it was not until childhood was viewed as a critical phase in people's development that the importance of play was properly acknowledged.

The time span that corresponds to the conceptual frame of childhood was not clear until recently. The idea that childrenin the Middle Ageswere treated like miniature adults¹as soon as they could walk and talk was a common idea. However, unlike the general view of the day, in the nineteenth century Rousseau opposed such an idea and only in the twentieth century emerged the first attempts to frame scientifically the role of play.

Play is one of the basic needs of a child, inherent to their physical, social, emotional and cognitive development, which facilitates communication, expression and creativity in socialisation and adaptation to people and environments²,3. Among the current concerns about the effects of the environment on child development is the effect of hospitalisation.

When in hospital, children undoubtedly become more vulenrable as they have to cope with unknown people and the barriers imposed upon their routine, namely being away from their home, friends, school and personal belongings. Additionally, their body may be subjected to painful and uncomfortable procedures. All these factors may constitute a rather stressing experience that may affect their psychological state.

Such experience does not aid their recovery and may even inhibit child development, as it often causes pain, suffering, irritability, regression and low immunity that at times are associated with inappropriate physical conditions, hospital care and quality of relationship with health professionals. In order to mitigate these negative effects, playful ornaments and playrooms have been used in paediatric wards4. Playrooms have been conceived of as a child-oriented laboratory, an environment where children are free to play and experience their emotions, abilities and creativity and thus, where they fulfil their essential need for play and become psychologically stronger5.

In Brazil, Bill no.2.087 of 1999 was passed into law (nº 11.104) on 21 March 2005 to ensure that children who are admitted into a paediatric ward are provided with a playroom6that must offer educational games and toys so as to encourage them and their family members to play together and develop a more supportive bond.

This study originated from the fact that there is little literature on this central theme and the belief that the child's representation of play during hospitalisation is worth investigating in order to foster more humane hospital care to support health recovery and better adaptation to this environment. The present investigation aims to determine not only children's social representation of the playroom, but also why they think this way so to shed light on the relationship between play and resilience.

This qualitative exploratory research is based on the Theory of Social Representation, which uses Story-Drawing as a tool for data. The study complies with provisions set forth in Resolution no. 196/96 of the Brazilian National Health Board7 pursuant to research with human subjects.

METHODS

This qualitative exploratory research was conducted at a reference paediatric in Juazeiro do Norte, Cariri region, Ceará state, between August and November 2012. The choice of this hospital was due to the fact that it is the only one in the region that provides health services through Brazil's Sistema Único de Saúde (equivalent to the 'Centralised Federal Health System'), and includes paediatrichospitalisation with a playroom that has been implemented pursuant to Law no.104\2005.

The sampling population comprised 12 children aged 6 to 11 years old, seven female and five male, who had been admitted to the paediatric ward. The choice of this year group as the subjects of research was based on Friedmann's8 discussion of Piaget's concept of children's play being mainly categorised by symbolic play and manipulating symbols during the pre-operational stage of cognitive development. This stage is between the emergence of language until approximately six or seven years of age. For these children, their observations of symbols exemplify the idea of play with the absence of the actual objects involved. Regarding the following phase of development, which starts at 6-7 years of age, the main functions performed by children are compensation, actual exercise of their desires, conflict resolution added to the pleasure of being subjected to reality and rule-determined games, in which rules presuppose that violating social or interindividual relations are not accepted and so a new element results from the collective organisation of play activities.

For data collection, the method chosen was story-drawing, since social representations are viewed as a projection of children's unconsciousness that can be captured. This qualitative exploratory research used direct non-participant observation for collecting data that referred to children's construction. Data analysis was supported by a literature review and direct non-participant observation, thus allowing the researchers to find relationships between theory, the research hypotheses raised and the data collected through the children's drawings and narratives.

An Informed and Freewill Term of Consent form was drawn up in compliance with the provisions set forth in Resolution no. 196/96 of the Brazilian National Health Board7 pursuant to research with human subjects. As the subjects were underage, the carer legally responsible for them was requested to sign this form so as to authorise their voluntary participation in this study. The executive-in-charge for the health institution where the study was conducted was also requested to sign an authorisation of their participation. This research was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee with Universidade Regional do Cariri - URCA, in Crato, Ceará state, and approved by Ceará's Basic Education Council as per Assent Procedure nº 133/2012.

FINDINGS

The sampling population comprised 12 children, seven female and five male. Data were collected from all 12 subjects, who had a clinical record of an infection and had been admitted for 2-4 days. Within this timeframe, only four children had previously been to the playroom and the other eight children only learned about it by the time of data collection. Nevertheless, all 12 children promptly accepted our invitation to play at the playroom, even though some of them did not know about it. Upon our invitation, their mothers were fully informed about the aims of this study and they all agreed to allow their child to become a volunteer subject. The interviews and the observation of children at play took place at the playroom.

Once in the playroom, children were asked to draw something that represented the playroom or that expressed how they felt then. They were then asked to explain the meaning of their drawing and were encouraged to speak at length about their feelings about the playroom and the hospital. After that, they were free to play as they wished for about 30 - 40 minutes.

It should be noted that as they accepted our invitation to go to the playroom, children were initially by themselves or interacted with their mother. However, they soon began to relate to other people as they moved around their hospital room, the ward corridors and the playroom; as evidenced by some studies9-10, play in the hospital environment promotes socialisation.

As the children participated in the proposed activities, it soon became clear that for them play was directly connected to the playroom, as most reported not playing in their hospital room or any other hospital environment. Their report showed that play within the hospital context is represented by the playroom. We did not intend to interpret the children's drawings, but rather to focus on the history represented by every drawing, the situations contextualised and symbolically experienced, as we sought to identify the meanings and symbols depicted in the drawings. To fulfil this aim, narrative was used. The subjects are identified by their initials and age.

The child herself/himself is depicted in both drawings above; Figure 1 shows the paediatric ward as represented by the hospital bed, and Figure 2 shows the playroom as represented by the table, pencil and paper. The feelings experienced by the child in each environment seem to be clear, as the subject described them using the terms "sad" and "happy", respectively, and drew her corresponding facial expressions.

MMNC described her drawing as follows: "This is me, feeling happy here in the playroom, this is the table, a pencil, a piece of paper. And on the other part of the drawing I am in my hospital room (...) sad in the room(...) this is the bed, the bed sheets, the pillow, and the wheels of the bed."

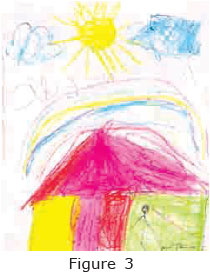

In this drawing the subject depicted a house where he is playing with a toy car and where he wrote "alegria", which means happiness in Portuguese. The drawing was thus described by the subject: "This is a toy car, this is me pulling the car and this is a door (...) clouds, sun shining, the house and that's it, this is the word 'alegria'."

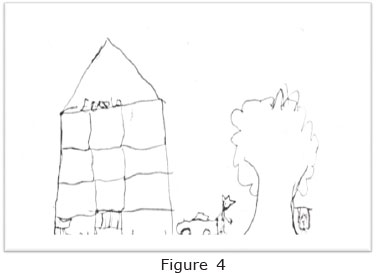

Figure 4 represents playtime during school break. The subject is playing with a toy car and his best friend is at the tree swing. Each square of the building is a classroom, one of the squares is the principal's room and another is the video room. This is how the subject described his drawing: "This is my school, this is me and this is my playmate, (...) this is a swing.(...) I'm playing with a toy car, these are the floors and the rooms of the classrooms,(...) the door, the principal's room and the videoroom where I watched films."

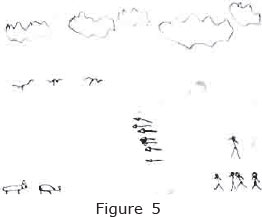

Figure 5 illustrates the conflict between men and tigers. The latter ate the men's baby because they were hungry and there was no food available. Interestingly, the subject draws tools that can hurt and kill - the arrows used by men. It is the men who eventually put an end to the story. In the subject's words: "These are the tigers and these are the men who will kill the tigers (...) because the tigers ate their baby, because they were hungry and had nothing to eat here (...) These are the arrows the men will use to kill the tigers, and the men will win, they will kill the tigers.

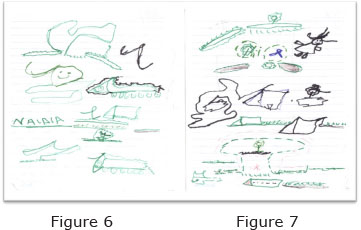

In both figures the child draws several small houses, roundnose grenadier - of which she reports to be afraid - flowers, dolls and a tree. It should be noted that at the bottom of Figure 6 the child drew a short person coming through the door and right above that a line, as she asked the name of the researcher of this study (Naidhia). When he was done, he said his drawing meant that the researcher had taken him to play in the playroom. This is what ACSF said: "This is a roundnose grenadier, I'm afraid of it, here the flowers, the doll and the tree (...), this is the hosue and this is you! You are here coming through the door." When asked about the researcher in the picture, ACSF went on: "This is you arriving and bringing me to play at the playroom."

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The children's representation of the playroom through their drawings

Anninge and Ring11 claim that children's drawings are windows to their understanding of the world and of their relationships with relevant people, things and places around them. Therefore, drawing becomes a tool for children to tell us about themselves; these are stories they develop. It may be argued that through play, drawings and creation children are able to build a relationship between their inner self and others, between their inner self and the outside world, between what is real and what is imagined, between their body and the world. Therefore, in the playful scenarios that children create, they represent their whole history and grant us access to this inconscious content which might not be otherwise so clearly depicted12.

Play functions as an emotional discharge for the young patient, which evidences its critical role in life and promotes a behavioural change. This becomes clear in Figure 1 and 2); although a hospital is a sad place associated with symptoms of illness, invasive clinical procedures and removal from the family environment and routine, Mussa and Malerbi10discuss the dichotomy between a hospital being viewed as a friendly environment because of the playroom - a place that enables play and encourages children to express their feelings and ideas about the situation they are going through - and being associated with sadness, fears and anguish. A hospital is also viewed as a place that helps children to get well and where they can play13. This dichotomy takes on a critical meaning as the playroom is able to change a child's view of a hospital since it is where the hospitalisation experience is less traumatic.

CLS's drawing (Figure 03) illustrates the concept of home. Of all the possible themes, the house is the clearest child's representation of the foremost environment to be explored, the symbol of a home and family - the nest of the child's first and decisive experiences, of his/her affective relationships, of the shelter against the unknown and threatening universe14. When asked about the meaning of home, CLS answered: "I like it. It means joy, it is good, it means friends, that's it."

As the playroom was where this drawing was made, it hints at the one place in a hospital where the child feels safe, feels closest to a pleasant homely environment, where he or she can be with other children and together they can do the one activity that is critical for their development - play. CLS also said: "The playroom reminds me of school and my friends."

The children's stories reveal that they feel healthy and at ease in the playroom, as if play could possibly restore their health. It seems that the children felt a relief from the effects of hospitalisation. In this respect, Moreira and Dupas15 argue that:

An illness is associated to barriers and limitations to what children like to do every day. For hospitalized children, this goes beyond and into feeling that their illness keeps them away from their family, their friends - it is an abrupt rupture in their daily life. It takes them way from home, and so home becomes an over-valued place to where they want to come back. They miss the people they love and playing with their dog and friends.

For Moreira and Dupas15, playing during hospitalisation allows children to accept more and cope with the situation they are experiencing and to feel at greater ease in hospital if the institution can prevent a rupture of their daily activities. Within this context, the child's social representation of the playroom relates to family, friends and school as well as health, which corroborates the hypothesis of this study that play has a positive effect upon a child's recovery.

When asked about what school stands for, MDF (Figure 4) said: "a good thing, for my learning, I miss school".

School is a recurring theme among hospitalised children, referred to as an integral component of being ordinary and healthy. So everyone who is healthy is not in hospital16. Chidlren's life revolves around school, as it is where they spend most of their time and where most of their friends are; that is, the one place for socialisation. A drawing unveils one's self-esteem, as represented in MDF's drawing (Figure 4) - the place where he also learns things. MDF also explained why he drew his school: "Because I think it is a good thing, as good as here [the playroom]."

The data collected match Motta and Enumo's findings17, which enphasise that as children are able to play when in hospital, and so they are able to approximate their experience to their reality, very positive effects can be observed in their recovery. These authors17 assessed what children think of playing during hospitalisation:

The fact that these children want to keep on playing despite being in hospital shows the positive effects this attitude brings about. As they play, they are able to reproduce their daily experiences in the hospital environment. The fact that they play with other hospitalized children shows a further approximation with their family and daily context.

It should be noted that the playroom in the children's drawings represents a place for socialisation, where they are able to enjoy themselves with other children just as they do in ordinary life. Thus, there is an approximation of their routine, which lends to their period of hospitalisation something that resembles home.

The conflict described by RRSF (Figure 5) between men and strong animals is closely linked to the situation they are experiencing in hospital: "Here the baby got out of the house and the tigers took him in because he was sick (...), tired, very tired, but his father only understood that later after he went after his child". The child's drawing contextualises and symbolises the hospitalisation period, in addition to functioning as a scaffold for the child's emotional system. Through free and spontaneous expression - which is also playful and enjoyable - pain, guilt, anguish, fear, death and other feelings that pertain to a sick child's context can be more easily identified and coped with12.

Therefore, the hospitalisaion period and the hospital itself are represented as aiding tools, treatment needs, support and recovery, as well as constituting a place that deprives the child of normal daily life, a place of confinement, suffering, exclusion and punishment18.

What RRSF tried to express in Figure 5 was that as the child was away from home, the tigers got him, thus revealing feelings like insecurity and fear towards the hodspital15. However, he repeated quite a few times that the men won. When asked about the reasons for drawing that scene, RRSF replied: "It is because good always wins, and I am a good boy here in hospital, you see, because there is a playroom."

According to Drummondet al.19, the playroom functions as a place that welcomes children and encourages them to share experiences in a therapeutical environment, as it allows them to structure their ideas in order to understand better what they are experiencing. RRSF's drawing and narrative support our hypothesis that using playful story-drawing aids children to understand better and cope with the hospitalisation period and that the playroom fosters this understanding and promotes the use of coping skills.

In their study of children who are admitted to a hospital for cancer treatment where a playroom encourages them to express their feelings of everyday life, Melo and Valle20 demonstrate that hospitalised children need to be in constant contact with other children or even with health staff who make these playful activities available and thus, provide them with a more humane care.

Our study has also evidenced the operational problems of a playroom, since playful activities are often times not an integral component of a health institution routine. Children are always expecting someone to take them away from the paediatric ward to play, as explained by ACSF (Figure 6 and 7): "This is you arriving and bringing me to the playroom to play."

Well-structured group work performed by health professionals, volunteers and also by patient relations, each doing what they are able in order to encourage play as a facilitator of treatment for hospitalised children, could greatly contribute to solve the problems assessed in the playroom regarding operating issues10,21.

However, we are led to believe that as corroborated by the evidence collected through the children's story-drawings and narratives, supported by the literature on this issue, once these problems are overcome, the playroom is likely to become a catalyst of better adaptation to the hospitalisation context and the faster recovery of children. And this is due to the fact that the playroom allows children to feel safe and in an environment where the routine is as close as possible to that in their own home.

Resilience: play vs hospitalisation

The conditions of the hospital environment have to be carefully considered with respect to the support that this provides children who are away from home. The hospital playroom can provide this type of support - which is also emotional - because children feel protected in the playroom.

Play may have therapeutical effects upon children, as it allows them to restructure mentally and emotionally the experience they are going through and, therefore, to view it from a more positive perspective. For this reason, we contend that play represents a protection factor against risk factors that may become a traumatic experience for chidlren22. Some parts of the children's narratives in relation to the playroom corroborate our hypothesis:

"Well, I was sick but here I am better" (CLS, six years old).

"This is a good place, I feel good in here" (MPFS, six years old).

"The playroom is beautiful, it's cool, I'm happy here" (RSST, 10 years old).

"This place is cool, I feel better here" (RRSF, six years old).

"I like it, it's beautiful, (...) cool, here I feel better" (SDD, nine years old).

The ability to face risk factors and benefit from protection factors makes individuals more resilient.23

According to Sapienza and Pedromonico23, children take ownership of the tools that can work as protection factors for them - in this case play activities and the playroom environment - and allow them not to think about the hospitalisation experience as long lasting but as a period of time that will be overcome. Considering that resilience also depends on other factors that are intrinsic to each child, getting over the hospitalisation experience may be processed more or less intensively by each child24.

Therefore, it is worth noting that some children did not find it so easy to relate to the researcher and to the toys when they were first taken to the playroom. Their level of ease was also susceptible to the constant change of activities and toys.

Inadequate play and difficulty to relate to the toys may be connected to traumatic disruptions or conflicts experienced by each child22. According to Sapienza and Pedrômonico23, the ability to be resilient also depends on the traumatic experiences a child has already gone through. Some of the children's narratives may justify why hospitalisation is a risk factor: "There in my room I felt stressed because there was nothing to do, there was no toy, there was nothing" (SFS, six years old); "All I do is lie down here [ward], this is bad" (MDF, nine years old).

Other children said they did not play in their hospital room but would like to go to the playroom more often. This shows a lack of encouragement for play to occur. Regular play allows children to look forward to a safe future and to be able to cope with changes22. Only one child, RRSF, who is six years old (Figure 5), said that he played in the ward: "I play in my room, with my toy figure and my dog." When asked if that was a teddy dog, he replied:"Not at all, He does not exist! He is a make-believe entity, invisible, and I've brought him along to play with me."

The story constructed by RRSF underscores that his need to play and interact with an imaginary dog, one that only exists in his mind, made the hospital environment easier to cope with and less distressing nostalgic. These are intrinsic factors related to resilience and the imaginary interaction was a way for this child to be more resilient. Assessing resilience means going beyond understanding risk factors. Protection factors are critical elements to help children become more resilient24.

In conclusion, play in the hospital environment relies heavily on there being a playroom, which, in children's representation, is a place that fosters socialisation and recovery, where they can imaginatively manipulate the surrounding environment to approximate reality or to transform the situation they are experiencing into something pleasant and familiar. Additionally, other representations were assessed, like family, friends, school, better health and feeling welcome.

It was also observed that play changes previously established meanings or ideas about a hospital, which then starts to be viewed as a place that promotes wellbeing and pleasure and where children can play.

Therefore, this study has proven that the playroom can aid children's adaptation to the new situation they have to cope with and also foster faster recovery. We highlighted the importance of non-participant observation in research involving children as subjects, as story-drawing allows to be assessed behavioural features that are inherent to balance play and hospitalisation as a risk factor for mental health.

It is clear that although resilience has been little studied, it is a relevant issue for at-risk children, as each child holds instrinsic factors and has undergone different traumatic experiences. We have assessed, however, that play seems to be the only protection factor for children who are in hospital.

It should be noted that this study presents the contribution of story-drawing as a technique to be used by nurses in caring for children, as this playful activity allows to be assessed unconscious stories constructed by children which might not be otherwise assessed.

Finally, although the mandatory implemen-tation of a playroom in health institutions with a paediatric ward means a great advance with respect to public policies, especially more humane care, some challenges remain. Among them is the need for a health professional responsible for the logistics and hygiene of the toys, as well as for setting a routine for play, since this study observed that some of the children did not know there was a playroom in the hospital - although they had been hospitalised for some time. Additionally, some of the subjects' narratives evidence their need to go to the playroom more often.

REFERENCES

1. Puga EMGR, Silva LSP. A brinquedoteca na escola: possibilidade do resgate do lúdico ou recurso da prática pedagógica. Aracaju, 2006. Disponível em: <http://lisane.pro.br. Acesso em: 03/03/2011. [ Links ]

2. Maluf ACM. Brincar - Prazer e Aprendizado. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2003. p 26-28. [ Links ]

3. Caldeira VA, Oliver FC. A criança com deficiência e as relações interpessoais numa brinquedoteca comunitária. RevBras Crescimento Desenvolv Hum 2007; 17(2): 98-110. [ Links ]

4. Pérez-Ramos AMQ. O ambiente na vida da criança hospitalizada. In: Bomtempo E, Antunha EG, Oliveira VB. Brincando na escola, no hospital, na rua. 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Wak editora, 2008. p. 111-127. [ Links ]

5. Schlee AR. Brinquedoteca: uma alternativa espacial. In: Santos SMP. (Org.) Brinquedoteca: a criança, o adulto e o lúdico.6.ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2008.p.12. [ Links ]

6. Brasil. Lei nº 11.104, de 21 de março de 2005. Dispõe sobre a obrigatoriedade de instalação de brinquedotecas nas unidades de saúde que ofereçam atendimento pediátrico em regime de internação. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 22 mar. 2005.Seção 1, p. 1. [ Links ]

7. Brasil. Conselho Nacional de saúde. Resolução 196/96 Decreto n° 93.993 de janeiro de 1987. Estabelece critérios sobre pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. Bioética. Brasília, v.4, n.2, suplemento, 1996. [ Links ]

8. Friedmann A. Brincar: crescer e aprender - O resgate do jogo infantil. São Paulo: Editora Moderna, 1996.p. 10-24. [ Links ]

9. Mitre RMA, Gomes R. A promoção do brincar no contexto da hospitalização infantil como ação de saúde. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva, 2004; 9: 147-154. [ Links ]

10. Mussa C,Malerbi FEK. O impacto da atividade lúdica sobre o bem estar de crianças hospitalizadas. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática - 2008, 10(2):83-93. [ Links ]

11. Anninge A,Ring K. Os significados dos desenhos de crianças. Artmed. Porto Alegre, 2009.p. 131-147. Tradução Magda frança Lopes. [ Links ]

12. MartinsMR. As representações gráficas no brincar da criança hospitalizada. UDESC em ação.[periódico na internet] 2008 [Acesso em 04 setembro 2011]; 2(1):1-10. Disponível em: http://revistas.udesc.br/index.php/udescemacao/article/viewFile/1710/1351. [ Links ]

13. Quintana AM et al. A vivência hospitalar no olhar da criança internada. Cienc. Cuid. Saude. UEM. [periódico na internet] 2007 Out/Dez [Acesso em 15 abril 2011]; 6(4): 414-423,. Disponível em:<http://periodi-cos.uem.br. [ Links ]

14. Mérediu F. O desenho infantil.11. ed. São Paulo: cultrix, 2006.p.61-82. [ Links ]

15. MoreiraPL, Dupas G. Significado de saúde e de doença na percepção da criança. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem. 2003 nov\dez; 11(6): 757-762. [ Links ]

16. Fontes RS. O desafio da educação no hospital. Presença Pedagógica jul./ago. 2005; 11: 21-29. [ Links ]

17. Motta AB,Enumo SRF. Brincar no hospital: estratégia de enfrentamento da hospitalização infantil. Psicologia em estudo. [periódico na internet] 2004 jan/abr [Acesso em 18 outubro 2011]; 9(1):19-28. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S141373722004000100004&script=sci_ arttext. [ Links ]

18. Ribeiro CR, Pinto Júnior AA. A Representação Social Da Criança Hospitalizada: Um Estudo Por Meio Do Procedimento De Desenho-Estória Com Tema. Rev. SBPH.[periódico na internet]2009[Acesso em 16abril 2011];12(1):31-56. Disponivelem:http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1516&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt. [ Links ]

19. Drummond I et al. A inserção do lúdico no tratamento da SIDA pediátrica.Análise Psicológica.[periódico na internet] 2009 [Acesso em 08 setembro 2011]; 1(27):33-43. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.oces.mctes.pt/pdf/aps/v27n1/v27n1a03.pdf. [ Links ]

20. Melo LL, Valle ERM. A Brinquedoteca como possibilidade para desvelar o cotidiano da criança com câncer em tratamento ambulatorial. RevEscEnferm USP. [periódico na internet] 2010 [Acesso em 03 outubro 2011]; 44(2):517-525. Disponível em: www.ee.usp.br/reeusp. [ Links ]

21. Azevedo ACP. Brincar na brinquedoteca: crianças em situação de risco. In: Bomtempo E; Antunha EG; Oliveira VB. Brincando na escola, no hospital, na rua... 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Wak editora, 2008. p. 143-161 [ Links ]

22. Oliveira LDB et al. A brinquedoteca hospitalar como fator de promoção no desenvolvimento infantil: relato de experiência. RevBras Crescimento Desenvolv Hum. 2009; 19(2): 306-312. [ Links ]

23. Sapienza G,Pedrômonico MR. Risco, proteção e resiliência no desenvolvimento da criança e do adolescente. Psicologia em estudo. [periódico na internet] 2005 mai/ago[Acesso em 15 outubro 2011];10(2):209-216. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pe/v10n2/v10n2a07.pdf. [ Links ]

24. Pesce R et al. Risco e Proteção: em busca de um equilíbrio promotor de resiliência. Psicologia: Teoria e pesquisa. [periódico na internet] 2004 mai/ago[Acesso em 04 setembro 2011]; 20(2):135-143. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ptp/v20n2/a06v20n2.pdf [ Links ]

Manuscript submitted Oct 08 2013

Accepted for publication Feb 22 2014

Corresponding author: naidhiasoares@hotmail.com

text in

text in