Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282versão On-line ISSN 2175-3598

J. Hum. Growth Dev. vol.25 no.3 São Paulo 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.106010

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Association between food consumption as predictor of cardiovascular risk and waist circumference increase in teenagers

Gustavo Carreiro PinascoI, II, V; Janine Pereira da SilvaI, III; Patrícia Casagrande Dias de AlmeidaI, III; Valmin Ramos da SilvaI, III, IV; Bárbara Farias de ArrudaI; Bruna Perim LopesI; Talita Cardoso CoelhoI; Luiz Carlos de AbreuII, V

ILaboratório de Escrita Científica. Departamento de Pediatria. Escola Superior de Ciência da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória (EMESCAM), ES, Brasil

IIPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde. Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, São Paulo, SP, Brasil

IIIPrograma de Pós-Graduação - Saúde da Criança e do Adolescente - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil

IVPrograma de Pós-Graduação. Mestrado em Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento Local. EMESCAM, ES, Brasil

VLaboratório de Delineamento de Estudos e Escrita Científica. Departamento de Saúde da Coletividade, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP, Brasil

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the eating habits of young people have changed significantly over the last few decades. Teenagers tend to have less than desirable intake of fruits, vegetables, dairy products and wholegrain products, and higher intake of foods high in saturated and trans fats, leading to increased waist circumference and consequent increased risk of cardiovascular disease

OBJECTIVE: to analyse the relationship between dietary intake as predictor of and increased abdominal circumference in teenagers

METHODS: a cross-sectional study was conducted in a sample of 818 teenagers aged between 10 and 14 years, of both genders, enrolled in state public schools in the metropolitan region of Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil, from August 2012 to October 2013. Waist circumference (WC) measurements were carried out in duplicate and the arithmetic mean was calculated. The dietary intake was identified from a simplified food questionnaire containing foods whose consumption is high or that present excessive risk of coronary heart disease in teenagers. The statistical analysis was done through Pearson's chi-squared test

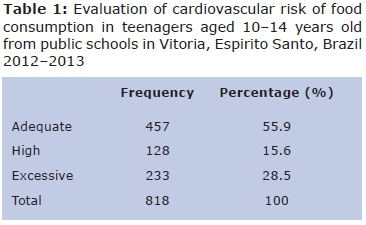

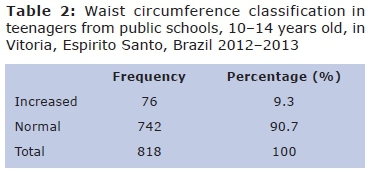

RESULTS: a proportion of 55.9% of the sample had an adequate food intake, 15.6% a high intake and 28.5% an excessive intake. Among teenagers who had an adequate, high and excessive dietary intake, 5.6% (N = 46), 1.1% (N = 9) and 2.6% (N = 21) had increased WC, respectively. The result of the chi-squared test indicated no association between dietary intake as predictor of cardiovascular risk and WC, p-value = 0.576

CONCLUSION: there was no association between dietary intake presenting cardiovascular risk and increased waist circumference

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, food consumption, teenager, waist circumference.

INTRODUCTION

The eating habits of young people have changed significantly over the last few decades. Studies show that teenagers tend to have less than desirable intake of fruits, vegetables, dairy products and wholegrain products, with a higher intake of soft drinks, sweets and fast food. As a result, most teenagers fall short of achieving optimal nutrient intake for healthy development1,2.

Obesity, hypertension and dyslipidaemia are closely associated with cardiovascular disease3 and the prevalence of these factors has increased in recent decades4. The Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES) 2008-2009 of the IBGE/Brazillian's Ministry of Health showed that the prevalence of excess weight between the ages of 10 and 19 years old in Brazil was 21.7% in boys and 19.4% in girls. A total of 5.9% of boys and 4% of girls were considered obese5. For dyslipidaemia, the prevalence varied between 24% and 33%6.

Simple anthropometric measurements such as body mass index and waist circumference have been used to investigate the association between adiposity and cardiovascular risk factors in adults7. Recently, studies in children and teenagers seem to confirm the usefulness of waist circumference as an appropriate indicator of metabolic and cardiovascular risk8-10 as it has a greater correlation with central adiposity, and is therefore considered an important factor in the evolution of cardiovascular disease11.

With regard to food consumption, there is strong and consistent evidence that good nutrition from birth brings great health benefits and the potential to reduce the future risk of cardiovascular disease12,13. Moreover, the ingestion of food with high fat content (especially trans fat), cholesterol and carbohydrates in childhood can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases manifested in adulthood, which makes early diagnosis key14.

Research in relation to food consumption in teenagers is growing15-19. For this, questionnaires for evaluating what kind of food is consumed and how often, reminders or surveys to assess dietary intake are used. These questionnaires are aimed at evaluating specific food types associated with the risk of developing certain types of diseases15,16,20.

There is little evidence of a relationship between increased waist circumference and eating habits as predictor of cardiovascular risk. Thus, this study aims to analyse the relationship between food consumption as predictor of cardiovascular risk and changes in waist circumference measurement in teenagers.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in a sample of 818 teenagers aged from 10 to 14 years, of both genders, enrolled in the public elementary schools of the metropolitan region of Grande Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil, from August 2012 to October 2013. The study was approved by the Ethical Committe of the Children's Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória, protocol 41/2012.

The sample size calculation was performed using the equation

n = z2αNp (1 - p)/e2 (N - 1) + z2αp (1 - p),

a considered error margin of 3%, a confidence level of 95% and a prevalence of overweight of 20%5. The number of students enrolled in the local public school system in the required age group was 27,787 teenagers leading to the sample size calculation of 822 subjects.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22 for Windows. We performed Pearson's chi-square test to check associations between dietary intake presenting cardiovascular risk and WC. Values of p <0.05 were considered significant along with a 95% confidence interval.

The public schools included in the study were randomly selected in order to maintain the distribution of the representative sample in the seven different cities (Victoria, Serra, Cariacica, Guarapari, Fundão, Viana and Vila Velha) that make up the metropolitan area of Grande Victoria, Espirito Santo, Brazil. The students were also selected randomly from different classrooms in the selected schools. A consent form was signed by the evaluated teenagers and their parents or legal representatives.

Individuals with secondary obesity, acute or chronic inflammatory diseases and who used corticosteroids and/or anti-inflammatory medicines were excluded due to their possible metabolic profile bias and body fat distribution.

Dietary intake was assessed using the simplified food questionnaire of Chiara and Sichieri16, which is composed of foods that represent a high or excessive risk of coronary heart disease: steak or roast beef, hamburger, whole cheese, French fries or chips, whole milk, cakes or pies, biscuits, sausage, butter or margarine.

Each food group was assigned a specific score associated with the frequency of consumption. To estimate the cardiovascular risk of food consumption, it was classified into appropriate (less than or equal to 100), high (between 101 and 119 points) and excessive or atherogenic (equal to or higher than 120 points).

Measurements of waist circumference were carried out in duplicate and the arithmetic mean was calculated. In cases where the difference between the two measures was greater than 1 cm, the measurement was repeated. All investigators were trained and standardized in the assessment of the measures. WC was measured at the umbilical level in millimetres with a tape measure at the end of a normal expiration, with teenagers in an upright position, with exposed abdomen, feet together and arms relaxed at their sides. The cut-off point as an indication of abdominal fat accumulation was proposed by Freedman et al18. WC higher than or equal to the 90th percentile, according to age and sex.

RESULTS

It was observed that most of the sample (55.9%; n = 457) presented adequate food consumption (Table 1). The prevalence of increased waist circumference was 9.3% (Table 2). Among teens who have had an inadequate food intake, 3.7% had increased WC (Table 3). Thus, it can be seen that there is no associations between dietary intakeas predictor of cardiovascular risk and waist circumference among the evaluated teenagers (p = 0.576).

DISCUSSION

There is little evidence of a relationship between increased waist circumference and eating habits as predictor of cardiovascular risk. In this study, we identified that 44.1% of the population concerned were at cardiovascular risk due to food consumption, and 28.5% consumed excessively.

Several studies have shown that inadequate food consumption in teenagers is significant in terms of changing factors related to increased cardiovascular risk, such as overweight, low fibre intake and high intake of carbohydrates and fats2,18. However, there isn't a well-established positive association between consumption as predictor of cardiovascular risk and changes in cardiovascular risk and changes in cardiovascular risk factors, such as increased serum cholesterol and changes in blood pressure levels2,21.

Some studies have developed streamlined and targeted questionnaires to assess the consumption of specific foods associated with risk of chronic disease2,19,22,23.

Chiara and Sichieri15 developed a simplified questionnaire to assess dietary intake associated with cardiovascular risk in teenagers between 12 and 19 years old. The selected foods for the simplified questionnaire were those that justified the variance of serum cholesterol by up to 85% and were important sources of total calories in the diet and of more atherogenic potential fats such as saturated and trans fats. Besides the convenience, another advantage of the questionnaire was that it had been used in the national population, making it more reliable for application in this study.

The prevalence of increased waist circumference in isolation was 9.3%, similar to that identified by Francis et al1 in a sample of 1317 students. However, in a study conducted in Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil, a 27.3% change in waist circumference was evidenced in 400 children and teenagers from 8 to 17 years old in public schools. In this study, the cut-off used for waist circumference was the midpoint between the last rib and the highest point of the iliac crest19.

Cavalcanti et al9 analysed 4,138 participants and showed a lower prevalence of 6.0%. In this study, they used the smallest circumference between the iliac crest and the ribcage as a reference point for waist circumference. It is possible that the discrepancy occurred due to different ways of measuring waist circumference, as well as social and economic differences among the compared groups.

In a literature review conducted in 2011 by Lima et al24, 42 national and international studies were evaluated, in order to identify the classifications and anatomical landmarks used in the measurement of central obesity. Difficulties were observed in comparing the results of the studies, as many authors use both the terms "waist circumference" (WC) and "umbilical waist circumference" (UWC) interchangeably. Internatio-nally, it can be seen that the term "WC" is most widely used, but often this is used to refer to the point at the level of the umbilicus.

The World Health Organization25 guides use the term "waist circumference" (WC) as the midpoint between the last rib and the upper border of the iliac crest and the term "umbilical waist circumference" (UWC) to refer to the point at the level of the umbilicus.

With regard to the anatomical point used, there is no consensus. Four measurement points were identified: the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest, the level of the umbilicus, the narrowest point between the rib and the iliac crest, and the largest circumference of the abdomen24. In this study, the level of the umbilicus was chosen due to its technical practicality. Thus, the lack of standardization for worldwide use makes it difficult to compare the results of different surveys.

The current literature shows that the association between abdominal obesity and cardio-vascular risk in adults is well established. However, in children and teenagers, although it needs further elucidation, some studies have shown a relationship between increased WC and other cardiovascular risk factors such as overweight10,26, dyslipidaemia19 and hypertension27.

Few studies have been developed with the objective of linking food consumption to varying WC. Cavalcanti et al9 studied the prevalence of abdominal obesity and its association with eating habits. In the analysis, WC was related to the frequency (daily or occasional) of the intake of fruits, vegetables and soft drinks. In this study, it was not possible to establish a relationship between WC and food consumption, because of the small group of food studied and because the prevalence of abdominal obesity was lower in those who occasionally consumed soft drinks than in those who occasionally consumed fruits and vegetables on a daily basis. In our study, although a larger group of food was studied but we could not find an association between inadequate dietary intake and increased WC.

In Francis et al1 analysis, no relationship was found between the consumption of fast foods and sweetened beverages and increased WC. This may be explained by a failure of the teenagers to report eating unhealthy foods during the dietary survey. It may also be related to the fact that information on food habits only takes into account the frequency of food consumption and not the size of the portions. However, on interpreting the data, a strong association was found between low consumption of fruits and increased WC. Similarly, this study also did not assess dietary intake by portions but by food frequency. In addition, the questionnaire is also likely to be subject to omissions and recall bias on the part of the participants.

Another study whose results converge was that of McNaughton et al2. In this, three food questionnaires were applied. The first evaluated the frequency of consumption, the second evaluatedthe quality of the diet, and the third was based on food intake recall for the previous 24 hours. According to the data, three dietary patterns emerged. In none of them was an association with WC found, in line with the present study.

There are some limitations that may have influenced the lack of a relationship between abdominal obesity and inadequate dietary intake: no evaluation of genetic factors associated, sedentary time and level of physical activity, also the study design may be influenced by memory bias and omission of data by the subject under study design, which means the study may be influenced by memory bias and the omission of data by the subject under study. Available evidence suggests that regular physical activity is inversely associated with WC9,10. Indeed, this was described in the study by Abreu et al16, in which active boys were less likely to have abdominal obesity than inactive boys. So this would be an important variable to be associated with cardiovascular risk due to intake of food and the measurement of WC.

Another important point is the sedentary time, in which studies have shown that longer exposure to sedentary behaviour (such as watching television for more than 3h/day) is directly related to increased cardiovascular risk10,28, and this is an important element to be evaluated in conjunction with the variables analysed in the study.

One cannot ignore the possible influence of genetic factors in the distribution of body fat. Fernandes et al29 concluded that excess maternal weight, and both parents being overweight, are familiar factors significantly associated with the presence of abdominal obesity in teenagers. This may indicate that even in children who have adequate dietary intake, the measurement of waist circumference may be increased, as seen in the present study.

Another bias found was the assessment of food consumption through a food frequency questionnaire. This made it impossible to estimate the amount of micronutrients, and the total calories, since the portion size of the ingested food was not evaluated. Moreover, its application was undermined by its dependence on the cooperation, reliability and memory of teenagers, which can lead to misinformation and omissions on the part of the participants.

There was no association between food intake as predictor of cardiovascular risk and umbilical waist circumference increase.

REFERENCES

1. Francis DK, Van den Broeck J, Younger N, McFarlane S, Rudder K, Gordon-Strachan G, et al. Fast-food and sweetened beverage consumption: association with overweight and high waist circumference in adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(8):1106-14. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980009004960 [ Links ]

2. McNaughton SA, Ball K, Mishra GD, Crawford AD. Dietary patterns of adolescents and risk of obesity and hypertension. J Nutr. 2008; 138(2): 364-70. [ Links ]

3. Caro FA, Martín JJD, Galán IR, Solís DP, Obaya RV, Guerrero SM. Factores de riesgo cardiovascular clásicos y emergentes em escolares asturianos. An Pediatr. 2011; 74(6): 388-95. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anpedi.2011.01.007 [ Links ]

4. Banzato RM, Bacci MR, Fonseca FLA, Bensi GC, Perestrelo BV, Chehter EZ. Hepatic function in obese adolescents and the relationship with hepatic steatosis. Int Arc Med. 2015;8(79):1-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3823/1678 [ Links ]

5. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. Diretoria de Pesquisas. Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento. Pesquisa de Orçamento Familiares 2008-2009. Antropo-metria e estado nutricional de crianças, adolescentes e adultos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão; 2010. [ Links ]

6. Giuliano ICB, Coutinho MSSA, Freitas SFT, Pires MMS, Zunino JN, Ribeiro RQC. Serum lipids in school kids and adolescents from Florianópolis, SC, Brazil - Healthy Floripa 2040 study Lípides. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;85(2):85-91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2005001500003 [ Links ]

7. Wahab KW, Sani MU, Yusuf BO, Gbadamosi M, Gbadamosi A, Yandutse M. Prevalence and determinants of obesity - a cross-sectional study of an adult Northern Nigerian population. Int Arch Med. 2011; 4: 10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1755-7682-4-10 [ Links ]

8. Maffeis C, Corciulo N, Livieri C, Rabbone I, Trifirò G, Falorni A, et al. Waist circumference as a predictor of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in obese girls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003; 57(4): 566-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601573 [ Links ]

9. Cavalcanti CBS, Barros MVG, Menêses AL, Santos CM, Azevedo AMP, Guimarães FJSP. Obesidade abdominal em adolescentes: prevalência e associação com atividade física e hábitos alimentares. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010; 94(3): 350-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2010000300015 [ Links ]

10. Letho R, Lahti-Koski M, Roos E. Health behaviors, waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio in children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(7):841-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.49 [ Links ]

11. Onat A, Avcý GS, Barlan MM, Uyarel H, Uzunlar B, Sansoy V. Measures of abdominal obesity assessed for visceral adiposity and relation to coronary risk. Int J Obes. 2004;28(8):1018-25. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802695 [ Links ]

12. De Kroon MLA, Renders CM, Van Wouwe JP, Van Buuren S, Hirasing RA. The terneuzen birth cohort: BMI changes between 2 and 6 years is most predictive of adult cardiometabolic risk. Plos One. 2010; 5(11): e 13966. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013966 [ Links ]

13. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. [cited 2012 Jun 11] Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/peds_guidelines_sum.pdf [ Links ]

14. Kuba VM, Leone C, Damiani D. Is wait-to-height ratio a useful indicator of cardiometabolic risk in 6-10 years old children? BMC Pediatr. 2013; 13: 91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-91 [ Links ]

15. Bel-Serrat S, Mouratidou T, Börnhorst C, Peplies J, Henauw S, Marild S, et al. Food consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in European children: the IDEFICS study. Pediatr Obes. 2013; 8(3): 225-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00107.x [ Links ]

16. Chiara VL, Sichieri R. Consumo alimentar em adolescentes. Questionário simplificado para avaliação de risco cardiovascular. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2001; 77(4): 332-6. [ Links ]

17. Abreu S, Santos R, Moreira C, Santos PC, Mota J, Moreira P. Food consumption, physical activity and socio-economic status related to BMI, waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio in adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2014; 17(8): 1834-49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013001948 [ Links ]

18. Vieira MV, Del Ciampo IRL, Del Ciampo LA. Food consumption among healthy and overweight adolescents. J Hum Growth Dev. 2014; 24(2): 157-62. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.81017 [ Links ]

19. Salvador CCZ, Kitoko PM, Gambardella AMD. Nutritional status of children and adolescents: factors associated to overweight and fat accumulation. J Hum Growth Dev. 2014; 24(3): 313-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhdg.88969 [ Links ]

20. Teixeira MH, Veiga GV, Sichieri R. Avaliação de um questionário simplificado de freqüência de consumo alimentar como preditor de hipercolesterolemia em adolescentes. Arq Bras Cardiol 2007;88(1):66-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2007000100011 [ Links ]

21. Freedman DS, Serdula MK, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of circumferences and skinfold thicknesses to lipid and insulin concentrations in children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 69(2): 308-17. [ Links ]

22. Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Rupp J. Screening measure for assessing dietary fat intake among adolescents. Prev Med. 2001; 33(6): 699-706. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.0951 [ Links ]

23. Smith KW, Deanna MH, Lytle LA, Dwyer JT, Nicklas T, Zive MM, et al. Reliability and validity of the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH) food checklist: a self-report instrument to measure fat and sodium intake by middle school students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(6): 635-47. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00161-4 [ Links ]

24. Lima CG, Basile LG, Silveira JQ, Vieira PM, Oliveira MRM. Circunferência da cintura ou abdominal? Uma revisão crítica dos referenciais metodológicos. Rev Simbio-Logias. 2011; 4(6): 108-31. [ Links ]

25. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [ Links ]

26. Taylor RW, Jones LE, Williams SM, Goulding A. Evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and the conicity index as screening tools for high trunk fat mass, as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, in children aged 3-19y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(2):490-5. [ Links ]

27. Welsh JA, Sharma A, Cunningham SA, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk among us adolescents. J Am Heart Assoc. 2011; 12393): 249-57. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972166 [ Links ]

28. Kelishadi R, Sadri G, Tavassoli AA, Khabazi M, Roohafza HR, Sadeghi M, et al. Cumulative prevalence of risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Iranian adolescents: IHHP-HHPC. J Pediatr. 2005; 81(6):447-53. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2223/JPED.1418 [ Links ]

29. Fernandes RA, Casonatto J, Christofaro DGD, Cucato GG, Oliveira AR, Júnior IFF. Fatores familiares associados à obesidade abdominal entre adolescentes. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2009; 9(4): 451-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-38292009000400010 [ Links ]

Manuscript submitted Oct 22 2014

Accepted for publication Dec 19 2014.

Corresponding author: Gustavo Carreiro Pinasco. E-mail: gustavo.pinasco@emescam.br

texto em

texto em