Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282versão On-line ISSN 2175-3598

J. Hum. Growth Dev. vol.28 no.3 São Paulo set./dez. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.152192

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of the Patient Safety Culture in the Western Amazon

Glauco M. da SilvaI, II; Marcos V. M. de LimaI, III; Marcos C. AraripeI, IV; Suleima Pedroza VasconcelosV; Simone Perufo OpitzV; Gabriel Z. LaportaI

ISetor de Pós-graduação, Pesquisa e Inovação, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP, Brasil

IICampus Floresta, Universidade Federal do Acre, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil

IIIDiretoria de Vigilância em Saúde da Secretaria de Estado de Saúde do Acre, Rio Branco, AC, Brasil

IVHospital de Saúde Mental do Acre, Rio Branco, AC, Brasil

VCentro de Ciências da Saúde e do Desporto, Universidade Federal do Acre, Rio Branco, AC, Brasil

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The safety culture of the patient is a contributing factor for the maintenance of the user's well-being in the health system because, through it, an organized systematization and quality of patient care are obtained, preventing possible intercurrences that can cause damages.

OBJECTIVE: To analyze the Patient Safety Culture (PSC) from the perspective of health professionals at the Reference Hospital of the Upper Juruá River, in the Brazilian Western Amazon.

METHODS: This is a cross-sectional study developed in a medium-sized public hospital in a municipality in Western Amazonia. The Survey for Patient Safety Culture survey of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality was applied to 280 professionals from December 2016 to February 2017. Descriptive analysis of the data and the internal consistency of the instrument were performed.

RESULTS: The results indicate the best evaluations in the dimensions of Teamwork in the scopes of the units (60%) and Organizational learning (60%). The aspects with the worst results were the dimensions of non-punitive responses to errors (18%) and frequency of events reported (32%). The internal reliability (Cronbach's Alpha) analysis of the dimensions ranged from 0.35 to 0.90.

CONCLUSION: The "culture of fear" seems to predominate in this hospital, however, the study showed that there is scope for improvement in all dimensions of CSP. The values of Cronbach's Alpha presented similarity to the results obtained by the validation process.

Keywords: organizational culture, patient safety, safety management, quality of health care.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the Patient Safety Culture (CSP) has been widely discussed at national and international levels, becoming an essential element for improving the quality of health services1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patient safety is defined as the least acceptable reduction in the risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care2.

Recent studies3-5 show that the number of deaths due to adverse health events is alarming. It is estimated6 that approximately 400,000 patients die annually from avoidable adverse events (AEs) and between two and four million events have serious consequences for the patient's health, but do not lead to death. Adverse events in hospitalized children compared to adults have increased threefold the likelihood of children being harmed7.

In Brazil, the CSP theme gained relevance with the creation of the National Patient Safety Program (PSNP) by the Ministry of Health in 2013. In this program, the safety culture was considered one of the main points of risk management for quality and patient safety. Therefore, CSP is the basis for the development of any type of safety program in hospital institutions, with emphasis on learning and organizational improvement8.

The evaluation of PHC in health intuitions is of fundamental importance for the promotion of safe care, since these studies point out the areas that need improvement. In the last decade, studies9-13 were developed with the purpose of evaluating CSP in different specialized care sectors, hospital institutions or in specific groups of health professionals, however no study has yet been published evaluating CSP in public hospitals in the Western Amazon.

Thus, evaluating the patient safety culture in a hospital complex in the Brazilian Western Amazon region is fundamental for improving the quality of care, as well as providing improvements in the work activity of the professionals of the hospital under study, in the various sectors and especially in values and beliefs shared by them in the caring process. The evaluation allows the identification of the fragilities and strengths experienced in the hospital environment scenario.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the Patient Safety Culture (CSP) from the perspective of the health professionals of the Reference Hospital of the Upper Juruá River, in the Brazilian Western Amazon.

METHODS

Study design

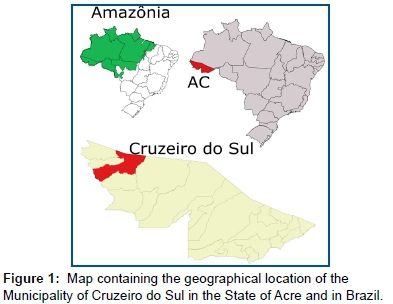

This is a survey14 study conducted at Juruá Regional Hospital (HRJ) between December 2016 and February 2017. HRJ is located in the municipality of Cruzeiro do Sul / Acre, with a 100% public, being the reference unit of the Health System of the Upper Rio Juruá Region, and also to the municipalities of the State of Amazonas such as Guajará, Erunepé, Ipixuna and Atalaia do Norte, and adjacent municipalities to Cruzeiro do Sul as Tarauacá, Feijó, Mâncio Lima, Rodrigues Alves, Porto Walter and Marechal Thaumaturgo (Figure 1).

Study population

HRJ currently has 118 beds divided into units of Medical and Surgical Clinic, Surgical Center, Intensive Care Unit and Emergency Room. In the year 2015, there were 8,200 hospitalizations and 445 hospitalizations in the Intensive Care Unit. HRJ is the reference unit of the Juruá Valley, and currently has 468 servers distributed in administrative and healthcare sectors, of which 280 accepted to participate in the survey, and a response rate of 59.82% was obtained. The professionals were invited to participate in the study on their shift and place of work, at which time they received two copies of the Informed Consent Term (TCLE). All the participants were previously oriented regarding the development and anonymity of the research. The research project was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal University of Acre, under reports No. 1,392,345 and 1,797,578.

Sample plan and inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study sample was intentional non-probabilistic. We included in the study all the health professionals who belonged to the effective staff of HRJ who had direct contact or direct interaction with the hospitalized patients, as well as the administrative professionals, who developed activities directly with patient care. Excluded were those health professionals who were not employed in the HRJ, such as: trainees of health professions, academics and residents.

The professionals who accepted to participate in the research answered the questionnaire with the help of a previously trained interviewer. The mean time of completion of the questionnaire was 20 minutes.

Data collection instrument

The analysis of the dimensions of the safety culture and the variables of the results measured by the research were obtained by the questionnaire called "Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture" (HSOPSC), prepared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The HSOPSC, which has been translated and validated into Brazilian Portuguese15,16, is a data collection tool widely used in international studies to measure safety culture among hospital professionals, whose work has a direct or indirect influence on care / care, whether they are health professionals or other areas, such as administrative or management17.

Reliability analysis

The reliability of internal consistency was examined by the Alpha (α) Cronbach calculation for items within the 12 dimensions of the questionnaire. Cronbach's α is a measure of the reliability of internal consistency of a measurement scale and evaluates the extent to which items within a given dimension are interrelated. The minimum criterion for acceptable reliability is α≥ 0.70. Reliability analyzes identify to what extent the measuring instrument, such as a survey questionnaire, consistently measures the desired construction. Cronbach's α ranges from 0 to 1, with the highest values indicating greater reliability18.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered in a spreadsheet in Excel®2013 for Windows® v.8.1 Pro. Subsequently, absolute and relative frequencies of each dimension were calculated and classified, according to the protocol suggested by AHRQ19. Regarding the sociodemographic data, these were analyzed through descriptive statistics. The reliability analysis was performed in the IBM® SPSS® v. 22.

RESULTS

The social and demographic characteristics of the participants of the questionnaire in the hospital under study are shown in Table 1. Of the interviewees, 30.71% and 17.86% work in the hospital emergency and in clinical wards, respectively. In relation to their positions, 54.64% are nursing technicians, 12.14% are nurses and 10.36% are doctors. In terms of working time in the hospital, 56.07% worked for more than 6 years in the institution. About the workload 70.71% answered that they work more than 20 hours a week and 25% have a workload between 40 and 59 hours.

Table 2 shows the 12 patient safety dimensions studied, with positive response rates ranging from 18 to 60%. The highest positive rates wee related to teamwork within the units and Organizational learning, both with 60%, the smallest was the non-punitive response to errors with 18%.

In addition to evaluating the dimensions of CSP, the HSOPSC also evaluates the items that structure the variable resulting from the safety culture, the first being the assignment of a note about patient safety in its work unit in the hospital, according to the individual perception, and the second the amount of adverse events reported by the professional in the last 12 months.

The patient safety note can be assigned according to a Likert scale, according to the data presented in Figure 2 - Panel A. Thus, the data demonstrate that 56% and 25% of the participants evaluated the patient safety in their unit as very good and regular, respectively. Regarding the second item of the outcome variable, which deals with the number of adverse events reported, it is observed that 82% of the professionals did not report any adverse events in the last 12 months. However, 18% reported at least one adverse event in that time period (Figure 2 - Panel B).

Instrument trustworthiness

The Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient (Table 3) was estimated for all items in the questionnaire (HSOPSC), which presented a global value of 0.90, and separately for the 12 dimensions, where the value ranged from 0.35 to 0, 90. The dimensions of "Frequency of related events" and "Expectations and actions to promote safety of supervisors and managers" presented the highest coefficients, 0.90 and 0.79, respectively. On the other hand, the "Staffing" and "General safety perceptions" dimensions presented the lowest coefficients, being respectively 0.35 and 0.37.

It should be noted that the authors of the HSOSPC, conducted a pilot test for the application of this instrument in 21 American hospitals, with 1,437 health professionals, and the alpha ranged from 0.63 to 0.8420. The studies in Brazil11,15,21 that also used the HSOPSC (Table 3) and presented the Cronbach Alpha values show results very similar to ours, reinforcing the applicability of the HSOPSC to the Brazilian context and the importance of this study for the Amazon Region.

DISCUSSION

The findings of the present study showed that the Patient Safety Culture has potential for improvement for most of the studied dimensions. Considering the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ) classification, it has been observed that no size can be classified as strong. This result may be associated with recent concern about the issue, noting that HRJ has not yet implemented the Patient Safety Nucleus as determined by the National Patient Safety Program. Moreover, six dimensions are presented as weak, namely: Feedback and communication about errors, General perceptions about patient safety, Staffing, Communication gap, Frequency of reported events and Non-punitive responses to errors.

There are dimensions that have presented as neutral and that may indicate the way to begin the planning of the CSP improvement in the hospital institution. The Teamwork dimension presented one of the highest percentages (60%), however when compared to a study carried out in Taiwan in 2010 with 349 hospitals, this dimension presented a percentage of 94%, showing a higher value than found in the present study22. When comparing this dimension between our study and other studies conducted in Brazil, we observed similar results, as in the study by Minuzzi et al.13, with 59 health professionals in an ICU, in which a positive response rate was obtained of 49, 99%, while Macedo et al.12, interviewing only members of the nursing team of pediatric units of hospitals in Florianópolis, found a rate of 62%.

The Organizational Learning dimension presented in this study a positive response rate of 60%, a result similar to that found in some international studies. In a study conducted in Turkey in four hospitals in the year 2015, the response rate was 68%23, but in Japan in 2014 this figure was 51%24. In Brazil, Santiago et al.25, interviewed 85 health professionals working in intensive care units of hospitals in São Paulo, found a percentage of 74.3%. Melo and Barbosa10, in 2013, with 97 health professionals, obtained a percentage of 45%.

In relation to the Openness dimension, the result of 34% was lower when compared to international and national studies. A study conducted in 126 hospitals in Lebanon in 2010, El-Jardali et al.26, found a percentage of 57.3%, and Chen et al.22 presented a rate of 58%. In Brazil, Tomazoni et al.27, in 2015, interviewed 141 nursing and medical professionals from hospitals in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil, reported that this dimension obtained 57% positive responses.

The present study presented a positive response rate of only 32% for the frequency of events reported, being lower than the average of other international studies. For example, Gama et al.28, interviewed 1,113 professionals from Spanish public hospitals in 2013, obtained a response rate of 44.8%, and Robida et al.29, when carrying out a survey of 976 health professionals in Slovenia in 2013, presented a 69% positive response rate. However, when comparing this dimension with Brazilian studies, Minuzz et al.13 obtained 24.84%, Macedo et al.12 evidenced 47% and Tomazoni et al.27 presented a 47% rate of positive responses. This dimension is important, since the professionals' responses may be directly related to the underreporting of Adverse Events (AD) of the team that acts in the patient care.

The study's CSP dimension for non-punitive error responses obtained only 18% positive response rate. For comparison purposes, Tereanu et al.30, in 2017, interviewed 479 health professionals from a public hospital in Italy, when a 40% rate, El-Jardali et al.31, was found in a study in the Lebanon, showed 24% and Eiras et al.32, when conducting a survey in Portugal in the year 2013, with 884 health professionals of a hospital intuition, obtained a 25% positive rate. In Brazil, Mello and Barbosa10 obtained a rate of 18% and Santiago et al.25 presented a rate of 29.6% of positive rate.

In addition, low Cronbach's alpha values were also found in the validation of the instrument in the Turkish (n = 309), Spanish (n = 174), Dutch (n = 583) and Japanese (n = 6395) versions15. Such studies emphasize that these results may have an influence on the size of the sample, because the larger the sample the greater the chances of repetition in the alpha analysis, and finally, the higher the alpha value33. In this way, the recommendations for use of HSOPSC in other studies in Brazil are reinforced, since only the instrument in different samples can be confirmed the validity and reliability of the same15.

Although strong dimensions were not evident for patient safety, most practitioners rated patient safety as Excellent (18%), Very Good (56%), and Regular (25%) in another national study12 participants rated patient safety as Regular (37%) and Very Good (35%), Excellent (8%). At the international level, a study conducted in Iran in 2017, with 205 professionals evaluated the patient's safety as very good (31.5%), regular (65%) and bad (3.6%)34.

These differences found in the evaluation of patient safety by health professionals in different institutions, care context and countries may be associated with the level of implementation of the safety culture. Being that this can stimulate the reflection and criticality of the professionals, influencing the evaluation of the patient's safety in the places where they work11,12.

Regarding reports of adverse events, the vast majority of professionals (82%) did not report in the last 12 months, which shows the absence of the Patient Safety Center in this institution, and only 18% reported at least 1 adverse event in the last 12 months. This reduced amount of may be associated with underreporting, a fact that generates damage for the entire hospital institution12.

In this sense, a study carried out with Brazilian nurses on underreporting identified 115 reasons for its occurrence or omission of communication of adverse events, being work overload, forgetfulness, non-valuation of adverse events and fear and shame the items they received greater emphasis on its occurrence35.

The CSP evaluation in health organizations has as main objective the promotion of safe care and indicates the areas that need improvement, help to direct the actions and attitudes, aiming at the best performance of the institution13. However, to better understand the organizational culture, several methods of measurement, including quantitative and qualitative research, are required. It illustrates only one form of measurement, as presented in the present study, may not reflect actual patient safety behavior, resulting in an incomplete measurement of CSP3.

The culture of fear is a constant within the hospital unit which can lead to a number of problems for Patient Safety. It is necessary to create a positive safety culture characterized by open communication based on mutual trust through the common perception among workers and managers of the importance of safety and the recognition of the effectiveness of preventive measures.

It is therefore necessary to promote a just culture in which careful and competent workers are treated differently when making mistakes, when compared to those who have a risky and unreasonably risky behavior.

It is fundamental to develop scientific research that addresses in detail each of the dimensions cited in the study so that it is possible to develop actions that allow professionals and managers to rethink CSP values. The present study brought a contextualized reality and, therefore, its results can not be generalized, however it can contribute with similar reality and serve as a comparison for other studies with the same proposal.

The Patient Safety Culture demonstrated potential for improvements in most of the analyzed dimensions, evidencing as a potential strategic planning tool for implementation and implementation of actions for patient safety in hospital follow-up.

REFERENCES

1.Reis AT, Silva CRA. Segurança do Paciente. Cad Saúde Pública. 2016;32(3):1-2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-311XRE020316 [ Links ]

2.World Health Organization (WHO). Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. WHO, 2009. [ Links ]

3.Groves PS. The Relationship between patient safety culture and patient outcomes: Results From Pilot Meta-Analyses. West J Nunsing Res. 2013;36(1):66-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945913490080 [ Links ]

4.Fujita S, Seto K, Ito S, Wu Y, Huang CC, Hasegawa T. The characteristics of patient safety culture in Japan, Taiwan and the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-20 [ Links ]

5.Wagner C, Smits M, Sorra J, Huang CC. Assessing patient safety culture in hospitals across countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(3):213-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzt024 [ Links ]

6.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press, 2000. [ Links ]

7.Patterson MD, Geis GL, LeMaster T, Wears RL. Impact of multidisciplinary simulation-based training on patient safety in a paediatric emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(5):383-93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000951 [ Links ]

8.Carvalho PA, Göttems LBD, Pires MRGM, Oliveira MLC. Cultura de segurança no centro cirúrgico de um hospital público na percepção dos profissionais de saúde. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2015;23(6):1041-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.0669.2647 [ Links ]

9.Rigobello MCG, Carvalho REFL, Cassiani SHB, Galon T, Capucho HC, Deus NN. Clima de segurança do paciente: percepção dos profissionais de enfermagem. Acta Paul Enferm. 2012;25(5):728-35. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002012000500013 [ Links ]

10.Mello JF, Barbosa SFF. Cultura de segurança do paciente em terapia intensiva: Recomendações da enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2013;22(4):1124-33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072013000400031 [ Links ]

11.Silva-Batalha EMS, Melleiro MM. Cultura de segurança do paciente em um hospital de ensino: diferenças de percepção existentes nos diferentes cenários dessa instituição. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2015;24(2):432-41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015000192014 [ Links ]

12.Macedo TR, Rocha PK, Tomazoni A, Souza S, Anders JC, Davis K. Cultura de segurança do paciente na perspectiva da equipe de enfermagem de emergência pediátricas. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50(5):756-62. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420160000600007 [ Links ]

13.Minuzz AP, Salum NC, Locks MOH. Avaliação da cultura de segurança do paciente em terapia intensiva na perspectiva da equipe de saúde. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2016;25(2):e1610015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072016001610015 [ Links ]

14.Blegen MA, Gearhart S, O'Brien R, Sehgal NL, Alldredge BK. AHRQ's Hospital survey on patient safety culture. J Patient Saf. 2009;5(3):139-44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f6e [ Links ]

15.Reis CT, Laguardia J, Vasconcelos AGG, Martins M. Reliability and validity of the Brazilian version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC): a pilot study. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32(11):e00115614. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00115614 [ Links ]

16.Reis CT, Laguardia J, Martins M. Adaptação transcultural da versão brasileira do Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: etapa inicial. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28(11):2199-2210. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2012001100019 [ Links ]

17.Halligan M, Zecevic A. Safety culture in healthcare: a review of concepts, dimensions, measures and progress. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(4):338-43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.040964 [ Links ]

18.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometertric Theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [ Links ]

19.Nieva VF, Sorra J. Safety culture assessment: a tool for improving patient safety in healthcare organizations. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2003;12(Suppl.2):17-23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii17 [ Links ]

20.Sorra J, Dyer N. Multilevel psychometric properties of the AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:199. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-199 [ Links ]

21.Tomazoni A, Rocha PK, Souza S, Anders JC, Malfussi HFC. Patient safety culture at neonatal intensive care units: perspectives of the nursing and medical team. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(5):755-63. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.3624.2477 [ Links ]

22.Chen IC, Li HH. Measuring patient safety culture in Taiwan using the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC). BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:152. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-152 [ Links ]

23.Güneş ÜY, Gürlek Ö, Sönmez M. A survey of the patient safety culture of hospital nurses in Turkey. Aust Coll Nurs. 2016;23(2):225-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2015.02.005 [ Links ]

24.Fujita S, Seto K, Kitazawa T, Matsumoto K, Hasegawa T. Characteristics of unit-level patient safety culture in hospitals in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:508. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0508-2 [ Links ]

25.Santiago THR, Turrini RNT. Cultura e clima organizacional para segurança do pacente em unidades de terapia intensiva. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(spe):121-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420150000700018 [ Links ]

26.El-Jardali F, Jaafar M, Dimassi H, Jamal D, Hamdan R. The current state of patient safety culture in lebanese hospitals: A study at baseline. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2010;22(5):386-395. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzq047 [ Links ]

27.Tomazoni A, Rocha PK, Kusahara DM, Souza AIJ, Macedo TR. Avaliação da cultura de segurança do paciente em terapia intensiva neonatal. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2015;24(1):161-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015000490014 [ Links ]

28.Gama ZAS, Oliveira ACS, Hernández PJS. Cultura de seguridad del paciente y factores asociados en una red de hospitales públicos españoles. Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29(2):283-93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2013000200015 [ Links ]

29.Robida A. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture in Slovenia: a psychometric evaluation. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2013;25(4):469-75. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzt040 [ Links ]

30.Tereanu C, Smith SA, Sampietro G, Sarnataro F, Mazzoleni G, Pesenti B, et al. Experimenting the hospital survey on patient safety culture in prevention facilities in Italy: psychometric properties. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2017;29(2):269-75. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx014 [ Links ]

31.El-Jardali F, Sheikh F, Garcia NA, Jamal D, Abdo A. Patient safety culture in a large teaching hospital in Riyadh: baseline assessment, comparative analysis and opportunities for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-122 [ Links ]

32.Eiras M, Escoval A, Grillo IM, Silva-Fortes C. The hospital survey on patient safety culture in Portuguese hospitals: instrument validity and reliability. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(2):111-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-07-2012-0072 [ Links ]

33.Maroco J, Garcia-Marques T. Qual a fiabilidade do alfa de Cronbach? Questões antigas e soluções modernas? Laboratório Psicol. 2006;4(1):65-90. [ Links ]

34.Sabouri M, Najafipour F, Jariani M, Hamedanchi A, Karimi P. Patient Safety Culture as Viewed by Medical and Diagnostic Staff of Selected Tehran Hospitals, Iran. Hosp Pract Res. 2017;2(1):15-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15171/hpr.2017.04 [ Links ]

35.Claro CM, Krocockz DVC, Toffolleto MC, Padilha KG. Eventos adversos em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva: percepção dos enfermeiros sobre a cultura não punitiva. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45(1):167-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342011000100023 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

glaucoczs@hotmail.com

Manuscript received: May 2018

Manuscript accepted: September 2018

Version of record online: November 2018

texto em

texto em