Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista de Psicología (Lima)

versão impressa ISSN 0254-9247

Rev. psicol. (Lima) v.25 n.2 Lima dez. 2007

ARTÍCULOS

Towards studies of organizational behaviour with greater local relevance

Hacia estudios del comportamiento organizacional con mayor pertinencia local

Peter B. Smith1

University of Sussex, UK

ABSTRACT

Theories of organizational behaviour mostly originated in North America. In testing their applicability elsewhere, attention must be given to differences in local environments and in the values of local employees. Within Latin America, the prevalence of high collectivism and power distance are particularly important. Employees attachment to their organization has been shown to differ within collectivistic cultures. The argument is illustrated by two Latin American studies. Firstly, the ways in which managers handle work events within Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Chile and Argentina are compared. Secondly, cross-national work problems of employees from these countries are surveyed. The results emphasize the need to take account of variability within the region, and the need to use measures that capture locally important issues.

Keywords: Culture, Organizational behaviour, Latin America.

RESUMEN

Las teorías del comportamiento organizacional se han originado principalmente en América del Norte. Al probar su aplicabilidad en otras regiones culturales, debe prestarse atención a las diferencias en los ambientes y en los valores de los empleados locales. Dentro de Latinoamérica, la prevalencia de altos niveles de colectivismo y distancia al poder es particularmente importante. En ese sentido, se ha demostrado que el apego de los empleados hacia su organización difiere dentro de las culturas colectivistas. El argumento se ilustra por dos estudios latinoamericanos. En el primero, se compara la forma en que los gerentes manejan los eventos laborales dentro de México, Colombia, Brasil, Chile y Argentina. En el segundo, se examinan los problemas laborales transnacionales de los empleados de estos países. Los resultados enfatizan la necesidad de utilizar medidas que capturen aspectos localmente importantes.

Palabras clave: Cultura, Comportamiento organizacional, América Latina.

Many of us spend a large proportion of our waking hours working in organizations. Employees job satisfaction is often linked to their overall satisfaction with life. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the various organizations in a society has a major impact on all members of that society. Understanding how organizations function and how they can operate more effectively is thus a major priority. One of the earliest attempts to explain how organizations function was made by the German sociologist Max Weber (1921/1947). His analysis focused upon the creation of bureaucratic rules and on the role of charismatic leaders in creating and maintaining a vision of organizational purpose.

The great majority of more recent theories concerning aspects of organizational behaviour have been formulated in North America. Psychologists have continued to see leadership as a key contributor to organization effectiveness, but have laid increasing stress on the various factors affecting employees motivations. Thus, we have theories of job satisfaction (Maslow, 1954), theories of organizational justice (Adams, 1963, 1965), theories of organizational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1997) and theories of organizational citizenship (Organ, Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 2005). These four theories have emerged progressively over the past decades and represent an increasingly precise focus on how employees are linked to their organization. Theories of job satisfaction initially reflected concerns with the types of work inducements that employees find attractive, while theories of justice concern what they see as fair reward for their contribution. Theories of commitment focus on employees emotional attachment to the organization, while theories of citizenship concern employees willingness to contribute to organizational goals in ways that are additional to their formal obligations.

North American theorists have also formulated numerous theories of leadership. Effective leadership entails management of the inherent conflict between achieving the organizations goals and facilitating the motives of employees (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek & Rosenthal, 1964). Early theories of leadership focused on the effectiveness of specific behavioural styles (Likert, 1961), whereas the more recent theories have laid greater stress on the leaders role in providing an empowering vision for subordinates (Bass, 1985).

The question of culture

Although the theories referred to above were developed and tested in North America, they have been become known in all parts of the world. This has occurred through business school curricula and programmes of management training staffed by those trained in North America. Furthermore, multinational business organizations, many of them headquartered in the US, have achieved increasing importance in most nations around the world, and they rather often implement human resource management policies which have been derived from the same theoretical bases.

Research into organizational behaviour in North America is conducted by skilled practitioners and the achievements of the past 50 years are impressive. Much of this research has been conducted with the US populations that are available to the researchers and without any assumption being made as to whether different results might be obtained elsewhere. The research strategy is what Berry (1969) has termed imposed- etic, in other words, the assumption is made that the same results would be obtained in studies undertaken elsewhere, until evidence is found to the contrary. Researchers in physics can safely assume that their studies will yield the same results wherever in the world a study is done. That assumption is more risky in the field of psychology.

A first step in identifying the nature of the risk was achieved through the pioneering study by Hofstede (1980). Through analysing averaged survey responses from the IBM company in each of 53 nations and regions (including Peru), Hofstede was able to identify dimensions that defined cultural differences between nations around the world. In particular, he noted a contrast between nations in which there was greater emphasis on individualism and nations where collectivism was more highly valued. Furthermore, he found that collectivist nations tend also to endorse hierarchy (which he termed power distance) more strongly than individualist nations. These contrasts are particularly important, since the US was found to be one of the most strongly individualistic nations in his sample, while nations in Latin America were among the most collectivistic. Hofstedes finding raises the possibility that US theories may rest on assumptions about employees holding predominantly individualistic values. In contexts where employees hold collectivist values, these theories may be found to work less well.

Since Hofstedes pioneering study, several other comparisons of values across large numbers of nations have been reported (Inglehart, 1997; Schwartz, 2004). Although it is often said that cultural differences are being reduced, the contrasts found by Hofstede are found also in the most recent studies. We therefore need to consider some of the evidence that is available as to what has been found when the better known US theories have been tested in nations that are relatively high on collectivism. This can be done by focussing on each of the theories in turn. Where I am aware of them, I refer to studies done in Latin America, but in some fields it may also be useful to draw on studies from other parts of the world.

Job satisfaction

Theories of work motivation were much influenced by Maslows (1954) theory of motivation. Maslow envisaged a hierarchy of motives, such that when more basic motives were satisfied, motives higher up the hierarchy became more salient. For instance when food and security needs are met, needs for connectedness with others and for status are said to increase. Maslow suggested that the highest motive was an individualistic need that could be fulfilled through use of ones own skills and abilities. US theories of work motivation have followed this assumption, predicting that employees would be more satisfied in jobs that give greater autonomy and use of individual skills (Alderfer, 1972; Herzberg, Mausner & Snyderman, 1959). However, in collectivist cultures it is possible that employees will be more strongly motivated by working with others and through the achievements of teams rather than as individuals.

Huang and van de Vliert (2004) were able to test for this possibility. They analysed job satisfaction ratings provided by nearly 130,000 employees from 39 nations, all of whom worked for the same organisation. They found that in individualistic nations white-collar employees were more satisfied than blue-collar employees. This is consistent with the US theories, because white-collar jobs typically give more autonomy than blue-collar jobs. However, in the data from collectivist nations there was no difference between the satisfaction level of white-collar and blue-collar employees. Indeed among the blue-collar employees, where job autonomy was lower, satisfaction was higher. This is consistent with the expectation that for these employees, working together would be more motivating than working individually. Thus there are important cultural differences in work motivations. However, not all motivations differ. In a separate study with another large sample, Huang and van de Vliert (2003) found that high pay was associated with high job satisfaction everywhere.

Organizational justice

Adams theory (1963, 1965) focused upon whether the employee feels that the exchange between him or herself and the organization has been fair. One basis for justice would be that each individual is rewarded in proportion to the amount and quality of work they do, which Adams refers to as equity. Another basis could be equality, where rewards are shared equally between members of a team. Studies have confirmed that equity, the more individualistic criterion, is favoured by US employees. Some theorists have argued that collectivist employees would favour equality, but this expectation has not been confirmed. For instance, Marin (1981) showed that Colombian students favoured equity even more strongly than US students. However, there prove to be many factors involved in which allocations are seen as most just. Collectivist cultures are often also hierarchical and a recent meta-analysis of studies conducted in many nations showed that nation-level hierarchy was the best predictor of preference for equity (Fischer & Smith, 2003).

Findings in this field have not been clear or consistent, for instance because preferences also vary depending upon who it is that allocates the rewards. More recently, researchers have also found it useful to distinguish between the actual rewards that are distributed and the procedures that are used to decide the allocation of rewards. Employees in less hierarchical nations may be more concerned that fair and bureaucratically defined procedures are used. In more hierarchical nations, employees may be more willing to grant their superior the right to decide what is fair. Consistent with this, Lam, Schaubroeck and Aryee (2002) found stronger effects of procedural justice in the US than in Hong Kong. Tests of this prediction within Latin America are required.

Organization commitment

Meyer and Allen (1997) distinguish three types of commitment to the organization. One may feel positive toward the organization that one works for (affective commitment), one may feel obligated to the organization (normative commitment) and one may decide not to leave the organization (continuance commitment). The three criteria of commitment are often positively associated, but they need not be. For instance, one may dislike ones organization but continue working for it because there are no other suitable jobs available locally. One might expect that affective commitment would be a particularly strong predictor in individualistic nations, because employees favour autonomy and are predisposed to seek other jobs if they do not find the present job rewarding. In collectivistic nations, we may expect normative commitment to play a stronger role because employees identity will be more strongly associated with others within their organization. Consistent with this, Borges Andrade (1994) found that in Brazil factors concerning the organization as a whole were stronger predictors of commitment than were relations with their immediate supervisor. In Turkey, Wasti (2003) compared employees who described themselves in more or in less collectivist ways. Among the collectivists satisfaction with ones supervisor predicted commitment. Among individualists, the nature of the work itself was a stronger predictor.

Organizational citizenship

Studies of organizational citizenship illustrate the most recent attempts of US theorists to identify ways in which the organization benefits from its employees commitment (Organ, Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 2005). Thinking of employees as citizens implies that they independently choose to advance the goals of the organization in ways that are additional to the obligations inherent in their specific job description. Consequently, it is easiest to identify good citizen behaviours when job descriptions are precisely defined. Reliance on job descriptions, and even whether such descriptions exist at all, varies between nations. There is therefore a strong possibility that what is considered outside ones specific role obligations in an individualistic nation might be within ones obligation in a more collectivist nation. Farh, Zhong and Organ (2004) compared managers perceptions of what constitute good citizen behaviours in China and in the US. Some common elements were found, but there were also distinctive behaviours within each nation that were not identified in the other nation. This study illustrates an important principle: when measures based on concepts developed by US theorists are used for studies in more collectivist nations, they will often require adaptation to fit local circumstances.

Leadership

Each of the concepts discussed in the preceding sections is frequently used as an index of organizational health, a benchmark whose level managers seek to enhance, while also achieving the organizations principal goals. Leadership is widely seen as one of the key levers in achieving this. Several large-scale surveys have compared leadership across nations. I focus here on two that have provided information whose relevance to Latin America can be explored, because sufficient detail is available. The most widely known is the project known as GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness) (House et al., 2004). These authors surveyed managers in 61 nations, asking them to identify leadership qualities that they perceived to lead to effectiveness. The sample included six nations from South America and four from Mesoamerica. Results from these ten nations were found to cluster together. Six leader styles were identified. Among these, Latin American managers scored highest on team-oriented leadership and lowest on autonomous leadership. They also scored high on charismatic or value-based leadership. Their scores on the other three dimensions were moderate. These dimensions are named as participative, humane and self-protective leadership.

These results are broadly consistent with Hofstedes (1980) earlier characterization of Latin American nations as particularly high on collectivism and power distance. However, while Hofstedes data simply summarised prevailing values, the GLOBE data summarises the leader actions that respondents perceive to be effective. They were also collected within the past decade and therefore confirm continuing cultural differences from other regions of the world. Although separate scores for leadership were computed by the GLOBE researchers for each of the national samples in their survey, these have not been published, so there is no way of estimating the degree of variability in leadership within the region from this study.

The second large-scale study was reported by Smith, Peterson and Schwartz (2002). In this survey, samples of middle-level managers in 62 nations were asked to describe the sources of guidance on which they relied in handling a series of relatively routine work events. For instance, one of the events was the appointment of a new subordinate. For each event, they were then asked to rate how much guidance they received from each of a series of eight different sources. For example, one source was the respondents own superior. The sources were selected in order to detect the various ways in which managers in different cultures might handle their responsibilities. In other words, rather than conceptualising leadership simply as a matter of superior-subordinate relations, leaders are seen within the broader context of the whole network of relationships with which they must contend.

In individualistic cultures, we may expect that the leader will rely strongly on his or her own experience and training in deciding how to handle events. In collectivistic cultures, it is likely that persons within the broader context will also be strong sources of guidance. The researchers selected eight sources for their study: 1) Formal rules and procedures; 2) Unwritten rules as to how things are usually done around here; 3) My subordinates; 4) Specialists from outside my department; 5) My co-workers; 6) My superior; 7) My own experience and training; 8) Beliefs that are widespread in my country as to what is right.

Data were collected from more than 8,000 middle-level managers in 62 nations. Overall, the results showed that managers reliance on their own experience and training was the strongest source of guidance in most nations. Ones superior and formal rules and procedures were also particularly salient sources of guidance. However, when the relative degree of reliance on these sources of guidance was compared, cultural differences are more clearly evident.

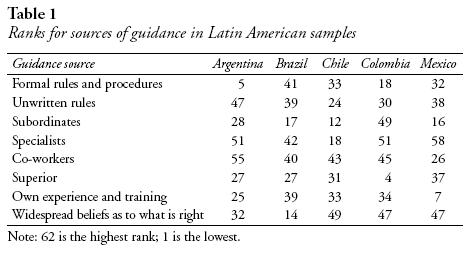

Data from the Latin American region were analysed by Smith et al. (1999), who compared profiles for respondents from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. More information was obtained subsequent to the publication of this paper, and Table 1 provides an updated summary of the results. Sample sizes varied from 300 in Mexico to 96 from Colombia. The samples from Mexico and from Brazil included respondents from several different cities, so that some account is taken of regional variability. Although the table only shows the results for Latin American respondents, the rankings are computed in relation to the responses from all the other nations that were also sampled. They therefore show what is distinctive to Latin America, but also how much variation is found within Latin America.

The table indicates that managers in all four of the South American samples show above average reliance on their co-workers, with this effect less strong in Mexico. This result is in accord with the finding by the GLOBE researchers that team-oriented leadership is strongly endorsed in Latin America. Across the region we also see moderate to high reliance on unwritten rules as to how situations are handled and on beliefs that are widespread as to what is right. In contrast, ranks are mostly lower for reliance on ones own subordinates and for reliance on ones superior.

In addition to these general trends, there are marked differences in the ranks obtained for each national sample. For instance, we find distinctively low reliance on specialists in Chile, low reliance on ones own experience in Mexico and low reliance on ones superior in Colombia. These results suggest that one should be very cautious in making generalizations about leadership in Latin America as a whole. There are certainly some common themes, but we need also to understand the meaning of the more local variations if research studies are to generate results that have practical applications.

Strengthening local understandings

The studies reviewed thus far in this paper have almost all derived from models and theories first formulated in North America. As was noted earlier, they can be described as imposed etic because their conceptual frameworks and methods of measurement are imposed on the local context. The alternative approach favoured by some researchers is known as the emic approach. From this perspective, more qualitative research methods are used at a particular location, so as to build a picture of what are the important issues in that location. This may lead in time to the development of more structured surveys, which can also contribute to global understandings (Smith, Bond & Kagitcibasi, 2006).

We can use a more emic approach in an attempt to understand some of the more surprising results from the two leadership surveys that have been described above. The GLOBE researchers found that charismatic leadership was strongly endorsed as effective within Latin America. However, Smith et al.s (2002) study found that managers in the region did not report strong reliance on their superiors as a source of guidance. This result was particularly strong in Colombia. Charismatic leaders are those who provide a strong and compelling vision to their subordinates, and the GLOBE results indicate that subordinates respond positively to such leadership. Why then should they consult their superiors relatively infrequently? To understand why this might be so, we need to consider some key elements of Latin American cultures.

Over several decades, ethnopsychological studies in Mexico by Diaz Guerrero (1993) identified traditional Mexican values as including affiliative obedience, machismo, family honour and fear of authority. Ardila (1996) reported similar results from Colombia. These studies emphasize a blend of respect for hierarchy with warm peer relations, particularly within the family, but they can also contribute an understanding of organizational behaviour. Where subordinates feel respectful and deferential toward their superior, they may well be reluctant to disagree with or query their superiors instructions. They will also be keen to impress their superior by their resourcefulness, and to avoid showing weakness by asking for clarification or assistance from their superiors. Given this lack of assistance from superiors, they would have to call on other sources of guidance available to them. On the basis of their experience as consultants, Osland, De Franco and Osland (1999) confirm that their Latin American clients often describe relying more on their peers than on their superiors.

A further widely noted element of Latin American cultures is the preference for maintenance of simpatía. Future emic studies in the region could benefit from examination of the ways in which organizational life occurs in ways designed to preserve simpatía. As an instance of what can be accomplished though emic studies, consider the case of Brazilian jeitinho. Analysts of Brazilian culture have identified jeitinho as a class of actions that are frequently employed as ingenious ways of achieving ones goals while preserving harmony, despite the presence of hierarchically imposed bureaucratic rules (Duarte, 2006; Neves Barbosa, 1995). There may be activities similar to jeitinho in many parts of the world, but its particular salience in that location makes it easier for it to be identified and studied. A closer examination of interpersonal relations among employees of other Latin American nations may reveal similar phenomena. The results from the Smith et al. survey (1999), showing strong reliance in Latin America on unwritten rules as to how things are usually done around here supports this expectation. Emic studies of this kind can provide a clearer understanding of the meaning of the results obtained from imposed-etic studies.

Coping with internationalisation

In the preceding sections I have discussed some approaches to studies of organizations based within collectivistic cultures. However, the current internationalisation of business is causing more and more work relationships to be cross-national relationships. This occurs especially within multinational organizations, but even within locally owned organizations, there are often cross-national relations with suppliers, with customers and with immigrant employees. It is important that crosscultural psychology study and help to understand the problems that arise in cross-national working and they may be overcome.

In a current study, more than 1,100 managers from many nations have briefly described an incident that occurred while they were working with someone from another nation. These incidents have been content analysed and summarised in terms of the nationality of the respondent and of the other party with whom they were working. Smith, Donoso Maluf, Torres and Perez (2007) have analysed the data received from Chilean, Brazilian and Mexican respondents. For all three nationalities, the most frequently reported problems were related to language. Language difficulties were reported twice as frequently by the Latin American respondents as by respondents from other parts of the world. Sometimes the language problem was attributed to the other party and sometimes to the respondent. When the other party was also Latin American, the next most frequently reported problem was excessive assertiveness by the other party. When the other party was from some other area of the world, the next most frequent problems were insistence on handling issues one at a time (monochronicity) and on following rules. Thus, the Latin American preference for flexibility and for handling several issues concurrently (polychronicity) is revealed. When asked how these difficulties were handled, emphasis on harmony was frequently reported where the other party was Latin American, whereas attempting to be patient was more frequent when the other party was from elsewhere.

These preliminary results indicate that distinctive attributes of Latin American cultures become especially salient when employees interact with persons from other cultures. It will become increasingly important for employees to develop the skills required to work effectively under such conditions. Some indications are available as to the general nature of these skills (Thomas & Fitzsimmons, in press), but more specific and regionally relevant studies will also be required.

Conclusion

The studies outlined in this article suggest many lines of further investigation. Studies that have been conducted within collectivistic nations in various parts of the world have confirmed that results do not always accord with those found in North America. The context of organizational life determines what is effective and what is not effective. The context of leadership comprises both the values and motivations of organization members and the environment within which organizations operate. In advancing the effectiveness of Peruvian organizations, psychologists can assist by clarifying work motivations, types of commitment and the local nature of organizational citizenship. More precise understandings can be achieved of the ways in which leaders relate to those around them. These types of study can be best accomplished if they include both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Organizations around the world are currently experiencing unparalleled turbulence and threats, due to rapidly changing markets and the electronic revolution. These processes are accentuating intercultural contacts and there is a particular need to explore the ways in which the policies of multinational organizations can accommodate local variations in values and practices.

References

Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 422-436. [ Links ]

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267-300). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, relatedness and growth. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Ardila, R. (1996). Ethnopsychology and social values in Colombia. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 30, 127-140. [ Links ]

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (1969). On cross-cultural comparability. International Journal of Psychology, 4, 119-128. [ Links ]

Borges Andrade, J. E. (1994). Comprometimento organizacional na administração pública e em seus segmentos meio e fim. Temas de Psicología: Psicología Social e Organizacional, 1, 49-61. [ Links ]

Díaz Guerrero, R. (1993). Mexican ethnopsychology. In U. Kim & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Indigenous psychologies: Research and experience in cultural context (pp. 44-55). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Duarte, F. (2006). Exploring the interpersonal transaction of the Brazilian jeitinho in bureaucratic contexts. Organization, 13, 509- 528. [ Links ]

Farh, J. L., Zhong, C. B. & Organ, D. W. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in the Peoples Republic of China. Organization Science, 15, 241-253. [ Links ]

Fischer, R. & Smith, P. B. (2003). Reward allocation and culture: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 251-268. [ Links ]

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. & Snyderman, B. B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1980). Cultures consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., Gupta, V. & GLOBE associates (2004). Leadership, culture and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Huang, X. & van de Vliert, E. (2003). Where intrinsic job satisfaction fails to work: National moderators of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 159-179. [ Links ]

Huang, X. & van de Vliert, E. (2004). Job level and national culture as joint roots of job satisfaction. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53, 329-348. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and post-modernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 43 nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D. & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Lam, S. S. K., Schaubroeck, J. & Aryee, S. (2002). Relationship between organizational justice and employee work outcomes: A cross-national study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 1-18. [ Links ]

Likert, R. (1961). New patterns of management. New York: Mc Graw Hill. [ Links ]

Marin, G. (1981). Perceiving justice across cultures: Equity versus equality in Colombia and in the United States. International Journal of Psychology, 16, 153-159. [ Links ]

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P. & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Neves Barbosa, L. (1995). The Brazilian jeitinho: An exercise in national identity. In D. Hess & R. Da Matta (Eds.), The Brazilian puzzle. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M. & MacKenzie, S. B. (2005). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature, antecedents, and consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Osland, J. S., De Franco, S. & Osland, A. (1999). Organizational implications of Latin American culture: Implications for the expatriate manager. Journal of Management Inquiry, 8, 219-234. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (2004). Mapping and interpreting cultural differences around the world. In H. Vinken, J. Soeters & P. Ester (Eds.), Comparing cultures: Dimensions of culture in a comparative perspective (pp. 43-73). Leiden, NL: Brill. [ Links ]

Smith, P. B., Bond, M. H. & Kagitcibasi, C. (2006). Understanding social psychology across cultures: Living and working in a changing world. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Smith, P. B., Donoso Maluf, F., Torres, C. & Perez, L. (July, 2007). Cross-national work relationships in Latin America. Symposium presented at the 32nd congress of the Interamerican Society for Psychology, Mexico City. [ Links ]

Smith, P. B., Peterson, M. F., DAmorim, M. A., Dávila, C., Gamas, E., Malvezzi, S. et al. (1999). Leadership in Latin American organizations: An event management perspective. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 33, 93-120. [ Links ]

Smith, P. B., Peterson, M. F. & Schwartz, S. H. (2002). Cultural values, sources of guidance and their relevance to managerial behavior: A 47 nation study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, 188- 208. [ Links ]

Thomas, D. C. & Fitzsimmons, S. R. (in press). Cross-cultural skills and abilities: From communication competence to cultural intelligence. In P. B. Smith, M. F. Peterson & D. C. Thomas (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural management research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Wasti, S. A. (2003). The influence of cultural values on antecedents of organizational commitment: An individual-level analysis. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 52, 533-554. [ Links ]

Weber, M. (1921/1947). The theory of economic and social organization (A. M. Henderson & T. Parsons, Trads.). New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Recibido: 13 de marzo, 2007

Aceptado: 25 de junio, 2007

1 Emeritus Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom. He obtained his Ph.D from the University of Cambridge in 1962. Former editor of the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Has broad interests in cross-cultural social and organizational psychology. Contact information: Department of Psychology, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QG, UK. E-mail: psmith@sussex.ac.uk