Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Summa psicológica UST (En línea)

versão On-line ISSN 0718-0446

Summa psicol. UST (En línea) vol.10 no.1 Santiago 2013

Artículos Originales

Academic cheating and gender differences in Barcelona (Spain)

Conducta deshonesta en el aula y diferencias de género en Barcelona (España)

Mercè ClarianaI; Mar Badia; Ramon Cladellas1,I; Concepción GotzensII;

I,Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB; Spain)

IIUniversitat de les Illes Balears (UIB; Spain)

RESUMEN

El presente estudio expone las características de la conducta deshonesta en el aula, describe sus causas y examina las nefastas consecuencias que tiene para el aprendizaje. Con el fin de analizar el estado de la cuestión en nuestro país, se ha hecho una entrevista psicoeducativa y se ha aplicado un cuestionario a un total de 306 alumnos de último curso de bachillerato, último curso de universidad y último curso de Psicología en Barcelona (España). Se ha comprobado que, igual cómo ocurre en otros países, más de la mitad de los estudiantes reconocen tener el hábito de copiar, y también que los chicos copian más que las chicas. Para finalizar, el trabajo expone estrategias operativas para controlar la conducta deshonesta en el aula, que incluyen: incorporar contenidos relacionados con la ética en el currículum, enseñar técnicas de análisis y resumen para evitar que los alumnos se vean obligados a copiar, y ser muy estrictos con las fechas límite y la aplicación de las normas en las instituciones educativas.

Palabras clave: conducta deshonesta en el aula, educación secundaria, universidad.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to present the issue of academic cheating, describe its causes, and examine the obstacles this behaviour creates for learning. The research was carried out with 306 students from Barcelona (Spain) which were administered both with a psycho educational interview and a questionnaire. Results are similar to those from other countries and show that more than half of the students are in the habit of frequently cheating, and that boys cheat significantly more often than girls. To finish, the text suggests teaching strategies to control academic cheating in educational institutions, such as: Being aware of the problem and taking the decision to tackle it, including ethics tuition in the curricular content, teaching summarising and rephrasing techniques, frequently revising students' writings, and last but not least, being very strict with deadlines and not accepting unwarranted excuses repeatedly made by students for not observing them.

Keywords: Academic cheating, secondary school, university.

Introduction

This article addresses the incidence of cheating in secondary school and university students. Fifty years ago, the topic did not arise much interest and nobody was paying attention to it but nowadays, with the increasing competence in the job market, the sometimes lack of ethic directions in school settings and in society in general, and the continuous inventions of new electronic devises, the subject has gained attention and popularity.

But what is cheating and to what extent is it a problem in educational environments? In general terms, cheating means breaking the rules to obtain better results than other people in a competitive situation, and yes, it is a problem because it is very common in both secondary and university students. As Roberts (2008), one of the more relevant experts in the field, poses: "Plagiarism (and academic cheating in general, we should add) no longer can be considered as a crime committed by a poor unfortunate few with questionable morals; rather, it is a crime committed by a significant number of students, perhaps the majority, at one time or another in their academic history" (p. 1).

Educational institutions usually generate two conditions: on the one hand they define sets of rules and regulations, which can be broken, and, on the other hand, they create especially competitive situations, which are due mainly to the needs of assessment and determining whether students have passed their exams. These two conditions either trigger or enhance academic cheating, thus, it is nowadays a common practice both in the United States and in Asia and Europe. Cheaters (American English) or cheats (British English) avoid regulations either when sitting tests or when doing class assignments, and usually gain academic advantages from it. Furthermore, as already mentioned, recent advances in technical devices, their affordable cost and the current lack of "cybercheating" regulations, make fraud at school more usual or "normal" (sic!) than ever, which utterly justifies a review and updating of this educational phenomenon.

Consequently, the present article aims to:

· Summarize the concept of academic cheating and show data for its current prevalence.

· Present the causes and academic correlates of this behaviour.

· Examine the inconvenience of academic cheating, with regard to both the quality of learning and the integrity of education institutions.

· Compare the academic cheating tendency between three samples of students: last year of secondary school or baccalaureate, university grade of psychology and university grades of other disciplines.

· Discuss and suggest instructional measures aimed at preventing or at least diminishing academic cheating.

Theoretical framework for academic cheating

Definition, prevalence and types of academic cheating

Academic cheating is the use of illegal actions as a shortcut to attain achievement. It is a common occurrence in the western and non-western world where more than 45% of students admit to frequently being dishonest, both at secondary school and university (from many sources, e.g. Harding, Mayhew, Finelli and Carpenter, 2007; Taradi, Taradi, Knežević & Đogaš, 2010; Ramzan, Munir, Siddique, & Asif, 2012).

Academic cheating has been reported to be more frequent in boys than in girls. According to many authors (Honny, Gadbury-Amyot, Overman, Wilkins, & Petersen, 2010; Kobayashi & Fukushima, 2012; Salleh, Hamid, Alias, Ismail, & Yusoff, 2011; Saulsbury, Brown, Heyliger, & Beale 2011), girls are less likely to cheat at school because they usually build a stronger sense of responsibility in order not no loose the path of their social group, and they praise more than boys the rules and regulation of the conventional society.

With regard to developmental characteristics, other experts explain that academic cheating generally begins at primary school (although its incidence is still minimal), becomes more widespread at secondary school, and is well established at the end of secondary school, graduate and even postgraduate educational levels (Anderman & Murdock, 2007).

In addition, all kinds of academic deception have been described, from the most frequent plagiarism or copying, to cybercheating or data fabrication, to mention but a few of the most popular illegitimate practices (Garavaglia, Olson, Russell & Christensen, 2007).

Reasons for academic cheating

The motives for cheating can be classified into two groups: the more intrinsic or individual and the more external or contextual.

In the first group, related to the intrinsic motives for cheating, Anderman and Murdock, in their excellent book Psychology of Academic Cheating (2007), mention two main reasons accounting for students' tendency to deceive: a lack of knowledge and the prediction of failure (Taradi, Taradi & Đogaš, 2012). Also, according to other authors, there is another significant condition: the lack of time (Anderman, Cupp & Lane, 2009). Nowadays everybody wants to be and to have everything. Consequently, in our competitive academic system each student wants to be better than the others, but they do not usually have enough time to complete this goal. So, students sometimes get despondent and are not able to learn the material, and on other occasions they procrastinate with their academic work. Then, when things are left to the last minute they have no option but to copy, invent excuses or fake their assignments in order to succeed.

Likewise, and with regard to individual differences, there is a general agreement that the tendency to cheat at school is more common in boys than in girls, in scientific subjects than in humanities, and in impulsive and narcissistic pupils that want to show off and have no feelings of guilt (Anderman et al., 2009; Brunell, Staats, Barden & Hupp, 2011; Karim, Zamzuri, & Nor, 2009; Miller, Murdock, Anderman & Poindexter, 2007). In addition, cheating has been found to correlate negatively with grades, and with other variables proven to ensure academic success, such as conscientiousness, self efficacy, learning motivation and more frequent class attendance (Yardley, Domènech, Bates & Nelson, 2009).

In the second group, which describes the external motives for cheating, some authors observe that certain academic characteristics trigger deceptive behaviour. For instance: traditional lessons involving little student participation; long periods of time between assessments; the stressed, burnt out and disengaged teachers (perhaps more common at high school due to discipline problems and the urgent need to achieve curricular targets); the physical distance in the classroom between the seat and the blackboard and teacher; and banal and repetitive curricular content. All these educational factors have been reported to increase the occurrence of academic cheating (Aydogan, Dogan & Bayram, 2009; Hart & Morgan, 2010; Nenty, 2001).

This second group of external causes of cheating should also include high pressure from parents, peers and instructors. The more competitive and selective instructional programs are, the more they seem to lead their participants to cheat in order to succeed and remain on them (Harding et al., 2007; Taylor, Pogrebin & Dodge, 2002). Particularly at the end of high school, a cluster of conditions can prompt cheating: very hard work is required to prepare for university entrance, the situation becomes extremely competitive and threatening, and the students are afraid of losing their way and getting left behind the others. All these elements can increase academic cheating (Surià-Martínez, 2011).

Inconvenience of academic cheating

Cheating in academia has many drawbacks and provokes many disadvantages both to the student who cheats and to the institution that allows it.

First of all, despite taking advantage of their dishonest behaviour, students that cheat only just manage to get by and pass their exams, but rarely get high marks or are the best in their year (Nenty, 2001).

Second, cheats usually focus on their outcomes and are only interested in getting diplomas and awards. Consequently, they miss out on the deeper concept of learning; they forget that they are taking a course mainly to change their previous ideas about reality and to mature personally (Taradi et al., 2012). Moreover, students who often cheat fail to notice the intense pleasure that meaningful learning creates, the "flow experience", which is the primary motive for studying and gaining knowledge (Csíkszentmihályi, 2006). Third, the aim of any educational institution is to prepare students to meet the needs of society. These requirements refer mainly to the knowledge set in the curricula and the professional skills derived from them. Thus, "ethicality" has to be taken into account in educational context, as it will guide the professional decisions that students will make in the future, which frequently has implications for them and others. Hence, to a certain extent, even when they pass their exams, cheats still fail them morally, because it shows that they have not understood the institution's ethical framework, and they are not able to analyse society's moral rules and implications (Bloodgood, Turnley & Mudrack, 2009).

And last but by no means least, academic honesty is essential to ensure the integrity of learning institutions. The educational assessment system and promotion scheme are based on honesty, and without it they lose all purpose and meaning. Education institutions should certainly be the first to be concerned about the issue, and should apply measures to eradicate academic cheating (Vinsky & Tryon, 2009).

Current measures used against academic cheating

Ethics tuition

Currently, the most prevalent remedy against academic cheating is to include teaching about ethics in the students' curriculum. The principal aim of these lessons is to change the students' moral system and to help them appreciate the harm they are causing when they behave dishonestly, first to themselves, as they only value grades and not true learning, and second to the integrity of the school system in general. In addition, an individual's intention to engage in cheating is a good predictor of their real dishonest behaviour and this intention is an attitude which can be modified through education as well (Harding et al., 2007).

Some experts have achieved acceptable results by conducting debates in class about the need to know and observe the codes of honour used in academic institutions. This type of practice has slightly but significantly diminished students' deceitful behaviour (Harding et al., 2007). It is also coherent with other results showing that Theology students cheat much less than students of Artistic disciplines, perhaps because of the different perceptions they have of the "creative resources" they can officially use in order to pass their exams (Miller et al., 2007).

However, other authors deny the power of in-class ethics tuition as a way to decrease academic cheating. In fact, sometimes when college students have been instructed with the aim of improving their convictions regarding the drawbacks and problems cheating can cause, no significant changes, either in their attitude or academic behaviour, have been reported (Vinski & Tryon, 2009). There are a variety of reasons for this failure. On the one hand, the individual's system of values is already set when they attend college and the motives for changing it may be somewhat vain. On the other hand, ethical tuition might not work equally well for all students. Oral information alone may cause some students to change their attitudes and behaviours, while others need a more continuous influence. And finally, there is still a third group of people, who will never change no matter how much they are encouraged to reject the option of academic cheating (Bloodgood et al., 2009).

Punishment

Other ways of dissuading academic cheating are the use of different kinds of threat and punishment, aimed directly at the potential cheat. Sometimes the school or codes of honour explain what happens if a student is caught copying or cheating. This may be a suitable approach to preventing dishonesty because the academic institution is expressing its concern about the subject and has devised ways to deal with it.

Nevertheless, punishment as a recurrent system to control behaviour is never welcomed by psychologists since it is well known that it presents many problems. As any educator knows, to be effective, the punishment has to be applied immediately after the mistake; every time it is applied it has to be more intensive to be useful; and last but not least, it does not show the learner how to behave, as it only focuses on negative responses.

All in all, students soon learn how to take or avoid the punishment and the cheating behaviour is not meaningfully reduced (Indermaur, Roberts, Spiranovic, Mackenzie, & Gelb, 2012; Jacobs, Sisco, Hill, Malter, & Figueredo, 2012).

Method

Participants

Participants were 306 students (63% females), 119 from baccalaureate (Bac), 147 from varied university grades (Uni), and 70 studying psychology (Psy) at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB; Spain). All of them were on their final year, which in Spain is 2nd for Bac and 4th for the Uni, and willingly accepted to be part of the study.

Procedure and Instruments

Other psychology students from the UAB carried out psycho educational interviews with the participants, in order to find out information about their academic habits and results. And they administered the participants with the Catalan version of the EDA questionnaire (Escala de Demora Académica; Clariana & Martín, 2008; Clariana, Gotzens, & Badia, 2011) as well. The EDA is a scale formed by 8 items aimed at assessing academic cheating, which split into two factors explaining 55% of the variance and which obtains a Cronbach's Alpha of .78. It takes less than five minutes to answer it and contains items such as: "I tell lies to my teachers" and "I copy my homework from the Internet". The students are asked to rate them in a Likert scale ranging from 1=Never to 5=Always.

Results

First of all, the general impression from the interview, which is used to corroborate the results of the questionnaires, is that great part of the students, more than 90%, and even the younger ones (aged 17), don't have problems telling that they have cheat, at least once, during their academic history. This outcome is really high and it is our opinion that as the researches were students as well, perhaps the interwees responded very frankly with regard to this issue.

In addition, from the results of the 8 questions of the EDA we see than approximately 50% of the students admit they cheat frequently. The questions casting higher results, or what is the same, getting a score of 3, 4 or 5 points in the Likert scale, are:

1. I tell lies to my teachers (45.3% of the sample).

2. I would cheat in a test to get a higher score (44.5% of the sample).

5. I tell the truth to my teachers (reversed) (53.8% of the sample).

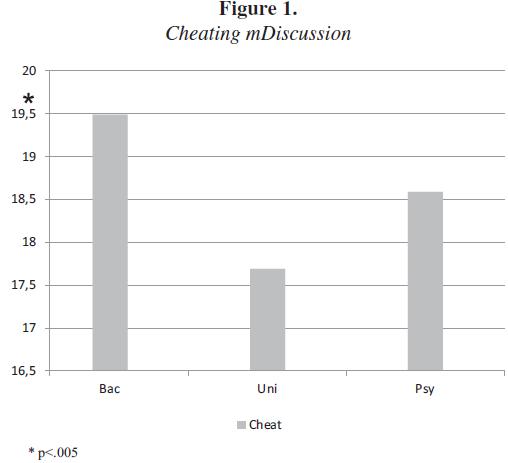

On the other hand, the results for academic cheating separated by gender are presented in Table 1 and show that males obtain a higher cheating score than females. Likewise, Figure 1 shows the cheating level in 3 groups of students, all in their final year. Several t-test series reveal that the students who cheat significantly more are the ones of baccalaureate. Conversely, between the other two sets of students, from varied university degrees and psychology, there are no differences.

Our data shows that both in last year of secondary school and in university, approximately 50% of the students from Barcelona (Spain) commonly cheat. This result is quite similar to those previously reported in other countries (Harding et al., 2007; Taradi et al., 2010; Ramzan et al, 2012), where more than 45% of students admit frequently cheating in order to get higher academic results. On the other hand, we have found that, in Barcelona (Spain), boys cheat significantly more than girls in academic settings. This result is also coherent with the findings of other authors (Honny et al., 2010; Kobayashi & Fukushima, 2012; Saulsbury et al., 2011), either from western or non-western societies, stating that male students, probably because they do not build such strong ties with their social rules and environment as girls do, are more frequently involved in school fraudulent behaviours. In addition, and also following the tendency reported in previous studies (Salleh et al., 2011, for instance), we have found that the younger the students the more they tend to cheat, as our pupils from baccalaureate obtained significantly higher cheating scores than those from university.

But in Spain there is also another very imporant cause explaining why baccalaureate students cheat more than university undergraduates. The fact is that baccalaureate is a very tough instructional period (Clariana, Gotzens, Badia & Cladellas, 2012), as it ends with a very selective and hard exam unavoidable to get access to the university.

With regard to this last aspect, several studies have shown that a teaching and learning environment based on competition, significantly and negatively affects crucial educational variables, such as school performance, problem-solving ability and learning cooperation (Orosz, Farkas & Roland-Lévy, 2013). Furthemore, years ago some classic texts about motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985) already suggested that academic competition decreases intrinsic motivation and severely undermines the process of building knowledge. And finally, Anderman and Murdock (2007) wisely wrote: "Competition is perhaps the single most toxic ingredient in a classroom, and it is also a reliable predictor of cheating" (p. XIII), and they report a significant and positive relationship between competitive educational settings and the extend to witch students cheat. Our results totally confirm this line of thinking, as the students undertaking the most competitive and selective academic course in the sample, baccalaureate, are the ones showing a significantly higher score in academic cheating.

In summary, our results show that at least 50% of the students from Barcelona are in the habit of cheating, males cheat more frequently than females, and all of them tend to cheat more often in baccalaureat when finishing secondary school than when they are about to end university.

All these findings have previously been reported for students in both Europe, Asia and America, but we have no notice of analysis carried out in Spain. Thus, this is the novelty of the study we are now presenting: It shows that Spanish teachers and lecturers are not free of this current academic plague, cheating. Consequently, in our opinion, they should take care of the matter. The reliability of our academic institutions is at stake and educational staff should aim to preserve and enhance it. In order to prevent our students from cheating, in the next section and to finish the writing we present some ideas which may be useful if not to completely stop this habit at least to better curb it.

Guidelines to prevent academic cheating

Although we are not promising any miracles here, we feel it is worth offering some guidelines about ways of preventing, identifying, diminishing or stopping academic cheating, especially when it has been stated that some instructional features increase its practice (Anderman & Murdock, 2007; Anderman et al., 2009). So, educators should not ignore cheating and it might be useful for them to bear in mind the following suggestions:

· They should educate their pupils on preventing academic cheating and plagiarism and kindly share with them their worries about the subject. Also, they should make sure the students are aware of the teacher's concern with regard to the problem. And finally, they should aim to a "zero tolerance" approach with regard to cheating and plagiarism in their academic environment (Wilson & Ippolito, 2008).

· Whichever the discipline is and as one of the causes of dishonest behaviour at school is the lack of meaningful learning skills, educators should help their students to learn how to summarize and rephrase in their own words. Being fluent at writing is possibly the best way of inhibiting cheating (Dick, Sheard & Hasen, 2008).

· Also with regard to plagiarism, teachers should find out about sometimes free Internet based programs and solutions, such as "The Plagiarism Checker" or "turnitinSafely.com", which would enable them to match students' texts with previous writings from other sources.

· Lecturers should be in the habit of constantly reminding their students about their assignments, publically praise the creative writers and generously welcome their originality.

· Also, they should openly honour their pupils' honest behaviour and publically discuss with them the so-called 'guts' that cheats are said to have. Conversely, educators should remark on how much braver it is to be sincere when more than 50% of students cheat.

· In order to be coherent and to reach the so-called zero tolerance towards academic cheating, teachers should hand out a course plan at the very beginning of the year, stick to it as far as possible, and frequently remind the students of it.

· Similarly, they should establish penalties for students that do not meet deadlines, and apply these penalties without exception. These consequences of not following the rules do not have to be severe –e. g., one mark less for every 24 hours that an assignment is late- but their application should be utterly strict.

· In addition, teachers should never accept students' excuses unless they are properly justified by a document such as a medical certificate or a form from a train company, for instance. It is not fair to allow students to hand in homework late and it is even less fair for the teacher to accept assignments when the marked ones have already been handed back. This situation, unfortunately not uncommon, reinforces students who usually cheat and procrastinate as they enjoy better conditions than the honest ones.

· Lecturers should also make sure their students correctly understand the terms and conditions of the course by discussing them in class if necessary. They should let the students know that the teacher is available at any time to help them with their academic problems and doubts.

· Educators should ask the students to hand in the drafts and preliminary forms of their writings, and value their progress, as well as their final grades.

· Teachers should avoid, as far as possible, the feeling of competition in class, and do not reiterate how hard it is to enter a specific school, or that it is the most prestigious and selective in the country. They should admit that all the students have their personal peculiarities, their strengths and weakness, and stress that learning is an enjoyable, life-long process.

· Moreover, teachers or school principals should publicly stop and punish the cheats when they catch them and make it evident that cheating is a risk that can carry very negative consequences.

On the whole, every time a dishonest student succeeds, if the teacher or the educational institution does not stop it, the bases for the emergence of new cheats are being laid. After all, if 50% of students usually plagiarise and cheat it is only because they manage to make it.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Nathalie Dettmer from the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster in Germany for her aid and inspiration. And for confiding in us, naturally.

Funding source

This project EDU2009_10651 is funded with support from the Spanish Ministry of Culture and Education. This funding source has provided resources both for gathering information and in writing this report.

Referências

Anderman, E. M., & Murdock, T. B. (2007). Psychology of academic cheating. New York (US): Elsevier. [ Links ]

Anderman, E. M., Cupp, P. K., & Lane, D. (2009). Impulsivity and academic cheating. Journal of Experimental Education, 78(1), 135-150. [ Links ]

Aydogan, I., Dogan, A. A., & Bayram, N. (2009). Burnout among Turkish High School teachers working in Turkey and abroad: A comparative study. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 7(3), 1249-1268. [ Links ]

Bloodgood, J. M., Turnley, W. H., & Mudrack, P. E. (2010). Ethics instruction and the perceived acceptability of cheating. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 23-37. [ Links ]

Brunell, A. B., Staats, S., Barden, J., & Hupp, J. M. (2011). Narcissism and academic dishonesty: The exhibitionism dimension and the lack of guilt. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 323-328. [ Links ]

Clariana, M., & Martín, M. (2008). Escala de Demora Académica. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 61(1), 37-51. [ Links ]

Clariana, M., Gotzens, C., & Badia, M. (2011). Continuous assessment in a large group of Psychology undergraduates. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(1), 95-112. [ Links ]

Clariana, M., Gotzens, C., Badia, M., & Cladellas, R. (2012). Procrastination and cheating from secondary school to university. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 10(2), 737-754. [ Links ]

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2006). A life worth living. Contributions to positive psychology. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and selfdetermination in human behavior. New York (US): Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Dick, M., Sheard, J. & Hasen, M. (2008). Prevention is better than cure: Addressing cheating and plagisrism based on the IT student perspective. In T. S. Roberts (Ed.) Student plagiarism in an online world. Problems and solutions (pp. 160-183). Hershey, NY (US): Information Science Reference. [ Links ]

Garavaglia, L., Olson, E., Russell, E., & Chistensen, L. (2007). How do students cheat? In E. M. Anderman & T. B. Murdock (Eds.) Psychology of academic cheating (pp. 33-55). New York (US): Elsevier. [ Links ]

Harding, T. S., Mayhew, M. J., Finelli, C. J., & Carpenter, D. D. (2007). The theory of planned behavior as a model of academic dishonesty in engineering and humanities undergraduates. Ethics & Behavior, 17(3), 255-279. [ Links ]

Hart, L., & Morgan, L. (2010). Academic integrity in an online registered course to baccalaureate in nursing program. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 41(11), 498-505. [ Links ]

Honny, J. M., Gadbury-Amyot, C. C., Overman, P. R., Wilkins, K., & Petersen, F. (2010). Academic integrity violations: A national study of dental hygiene students. Journal of Dental Education, 74(3), 251-260. [ Links ]

Indermaur, D., Roberts, L., Spiranovic, C., Mackenzie, G., & Gelb, K. (2012). A matter of judgement: The effect of information and deliberation on public attitudes to punishment. Punishment and Society. International Journal of Penology, 14(2), 147-165. [ Links ]

Jacobs, W. J., Sisco, M., Hill, D., Malter, F., & Figueredo, A. J. (2012). Evaluating theory-based evaluation: Information, norms, and adherence. Evaluation and program planning, 35(3), 354-369. [ Links ]

Karim, N. S. A, Zamzuri, N. H. A., & Nor, Y. M. (2009). Exploring the relationship between Internet ethics in university students and the Big Five model of personality. Computers & Education, 53, 86-93. [ Links ]

Kobayashi, E., & Fukushima, M. (2012). Gender, social bond, and academic cheating in Japan. Sociologial Inquiry, 82(2), 282-304. [ Links ]

Miller, A. D., Murdock, T. B., Anderman, E. M., & Poindexter, A. L. (2007). Who are all these cheaters? Characteristics of academically dishonest students. In E. M. Anderman & T. B. Murdock (Eds.) Psychology of academic cheating (pp. 9-32). New York (US): Elsevier. [ Links ]

Nenty, H. J. (2001). Tendency to cheat during mathematics examination and some achievement -related behaviour among secondary school students in Lesotho. IFE Psychologia: An International Journal, 9(1), 47-64. [ Links ]

Orosz G., Farkas D. & Roland-Lévy C. (2013). Are competition and extrinsic motivation reliable predictors of academic cheating? Frontiers Psychology, 87(4). DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg. 2013.00087 [ Links ]

Ramzan, M., Munir, M. A., Siddique, N., & Asif, M. (2012). Awareness about plagiarism amongst university students in Pakistan. Higher Education, 64(1), 73-84. [ Links ]

Roberts, T. S. (2008). Student plagiarism in an online world. Problems and solutions. Hershey, NY (US): Information Science Reference. [ Links ]

Salleh, M. I. M., Hamid, H. A., Alias, N. R., Ismail, M. N., & Yusoff, Z. (2011). The influence of gender and age on the undergraduate's academic dishonesty behaviours. In Sociality and Economics Development (pp. 593-597). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Book series 10, International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research. [ Links ]

Saulsbury, M. D., Brown, U. J., Heyliger, S. O., & Beale, R. L. (2011). Effect of dispositional traits on Pharmacy students' attitude towards cheating. Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 75(4), 1-8. [ Links ]

Surià-Martínez, R. (2011). Comparative analysis of students' attitudes towards their classmate's disabilities. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(1), 197-216. [ Links ]

Taradi, S. K., Taradi, M., & Đogaš, Z. (2012). Croatian medical students see academic dishonesty as an acceptable behaviour: a cross-sectional multicampus study. Journal of Medical Ethics, 38(6), 376-379.

Taradi, S. K., Taradi, M., Knežević, T., & Đogaš, Z. (2010). Students come to medical schools prepared to cheat: a multi-campus investigation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(11), 666-670.

Taylor, L., Pogrebin, M., & Dodge, M. (2002). Advanced placement - advanced pressures: academic dishonesty among elite High School students. Educational Studies, 33(4), 403-421. [ Links ]

Vinsky, E. J., & Tryon, G. S. (2009). Study of a cognitive dissonance intervention to address High School students' cheating attitudes and behaviors. Ethics & Behavior, 19(3), 218-226. [ Links ]

Wilson, F. & Ippolito, K. (2008). Working together to educate students. In Roberts, T. S. (2008). Student plagiarism in an online world. Problems and solutions (pp. 60-75). Hershey, NY (US): Information Science Reference. [ Links ]

Yardley, J., Domènech, M., Bates, S. C., & Nelson, J. (2009). True confessions? Alumni's retrospective reports on undergraduate cheating behaviors. Ethics & Behavior, 19(1), 1-14. [ Links ]

¹) Corresponding: Facultat de Psicologia, edifici B, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), 08193 Bellaterra. Spain. Telephone: +34035812101, Fax: +34935813329, E-mail: ramon.cladellas@uab.es.