Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Aletheia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-0394

Aletheia vol.49 no.1 Canoas jan./jun. 2016

INTERNATIONAL ARTICLES

Dreams and craving in crack/cocaine addicted patients in the detoxication stage

Sonhos e craving em dependentes de crack/cocaína internados para desintoxicação

Natália Vidal Scarparo Sório1; Carolina Silva Schiefelbein1; Alexandre Dido Balbinot1; Paola Lucena dos Santos1, I; Renata Brasil Araujo1, II

IUniversidade de Coimbra

IIHospital Psiquiátrico São Pedro

ABSTRACT

Background: There are some studies about of dreams suggesting an indicative of craving from dreams and demonstrating as a tool for evaluating risk situations for relapses. Objective: To verify, in patients addicted to crack/cocaine, the association between the presence of the crack content in dreams and craving increase. Methods: It is a clinical study, analytical, transversal type. We evaluated 51 patients who were admitted to Unit Detoxification. Results: We verified that 21 patients reported dreams with the crack, when 19.6% reported not awakening the craving after dreaming about crack, against 21.4% who woke up with this urge. Regarding the perception on the night before the dream of the crack, 17.5% thought they had presented craving for crack. No association was found between dream the crack and the craving (p=0.34). Discussion/Conclusion: Dreaming of the crack is not associated with an increase in craving in patients admitted for detoxification.

Keywords: Craving, Dreams, Crack.

RESUMO

Contexto: Existem alguns trabalhos abordando sonhos sugerindo que eles possam ser indicativos de craving e demonstrando como ferramenta de avaliação de situações de risco para recaída. Objetivo: Verificar, em pacientes dependentes de crack/cocaína, a associação entre presença do conteúdo crack nos sonhos e aumento no craving. Método: Trata-se de um estudo clínico, analítico, do tipo transversal. Foram entrevistados 51 pacientes que estavam internados na Unidade de Desintoxicação. Resultados: Foi verificado que 21 pacientes relataram sonhos com crack, onde 19,6% relataram não ter acordado com craving após ter sonhado com crack, contra 21,4% que acordaram com esta vontade. Em relação a percepção sobre a noite anterior ao sonhar com o crack, 17,5% julgaram ter apresentado craving pelo crack. Não foi encontrada associação entre sonhar com crack e o craving (p=0,34). Discussão/Conclusão: Sonhar com o crack não está associado a um aumento no craving em pacientes internados para desintoxicação.

Palavras-chave: Craving, Sonhos, Crack.

Introduction

Cocaine or crack are stimulants of the central nervous system which leads to a series of effects, including euphoria and state of alert, increased confidence, hyper sexuality, and indifference to problems and risks (Duailibi, Ribeiro, & Laranjeira, 2008; Mendelson & Mello, 1996; Bosque, 2004; Ferreira Filho, Turchi, Laranjeira, & Castelo, 2003). An increasing rise in consumption of crack, has been noted, for countless reasons, among them, greater availability, the low cost of this drug, and its faster peak action (Duailibi et.al.,2008; Mendelson & Mello, 1996; Bosque, 2004; Ferreira Filho et.al., 2003).

The craving is a term that refers to "fissura" in the Portuguese Language, is a subjective experience of an intense urge for a substance, and is a strong predictor for continuing its use and its relapses (Mendelson & Mello, 1996; Santos, Rocha, & Araujo, 2014; Kober, 2015; Tanguay, Zadra, Good, & Leri, 2015; Araujo, Oliveira, Pedroso, Miguel, & Castro, 2008; Kilts et.al., 2001). It consists of physical and emotional excitement associated to a strong urge to use the drug, apart from a behavioral impulse (action) involved (Santos et.al., 2014; Kober, 2015; Kilts et.al., 2001; Knapp & Baldisserotto, 2001). Craving can be verified through countless ways, among them: spontaneous report of the patient of a situation in which he felt the urge to the substance, through a daily log of dysfunctional thoughts, analysis of self-reports of craving intensity, and through the dreams that these patients have had (Ferreira Filho et.al., 2003; Tanguay et.al., 2015; Araujo et al,2008).

To dream is a physiological mechanism that is of vital importance in the balance of the entire organism (Bachtold, 1999; Delitti & Wielenska, 1999; Guilhard, 1995). The dream is a state of consciousness characterized by sensory, cognitive, and emotional experiences that occur during sleep. It tends to occur in several stages of sleep (Goyal et al.. 2013;Araujo et.al., 2008; Bachtold, 1999; Delitti & Wielenska, 1999; Guilhard, 1995). Reports of dreams tend to be particularly abundant, with complex, emotional, vivid experiences, especially when the person is woken in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Desseilles et.al., 2011).

The usage of dreams in behavioral therapy does not consist only of its report, the way of describing or narrating, as a function of a simple discrimination of covert events (Araujo et.al., 2008; Bachtold, 1999). There are at least three main aspects for using dreams in clinical practice: using dreams as an instrument for data collection; the dream as an instrument for therapeutic intervention; and reporting dreams as a way of reinforcing the bond between therapist-patient (Bachtold, 1999).

In Substance Use Related Disorders (SUD), there are some studies about the study of dreams, suggesting that they may be indicative of craving and demonstrating its utility in the therapy of the patients as a tool for evaluating risk situations for relapses (Colace, 2014; Araujo et.al., 2008; Beck, Wright, Newman, & Liese, 1999; Johnson, 2001; Reid & Simeon, 2001; Yee, Perantie, Dhanani, & Brown, 2004; Gillispie, n.d.; Christ & Franey, 1996). Christo and Franey (1996) found that 84% of 101 patients users of psychoactive substances dreamt about the drug, especially during abstinence. Yee et.al.(2004) reported that 26 out of 35 evaluated subjects with bipolar disorder dreamt about cocaine in 36 weeks evaluated, concluding that an elevated percentage of occurrence of this type of dream is common in the beginning of the abstinence period. To dream with the drug, in this study, was not associated with the occurrence of craving. The authors pointed out that, at baseline of treatment, the dream was not identified as a predictor of relapse, having as time of abstinence increases, a decrease in dreams with the substance (Reid & Simeon, 2001; Yee et.al., 2004).

Reid and Simeon (2001) analyzed that from 46 patients users of crack, 41 of them dreamt about the substance during the first month. In six months of following, however, this number dropped to 28 patients. The dreams of patients with less than 1 month of abstinence were focused on the use of the drug, while patients with 6 months of abstinence were more likely to dream about the refusal of crack. The study also highlights the importance of the content of the dream as an influential factor for maintaining abstinence.

A study (Tanguay et.al., 2015) was conducted to analyze the connection between dreaming of drugs, the presence of negative emotions during the day and the craving for a 5-week treatment program for crack addicts, alcohol and opioids. Dreaming of drugs was associated with high level of negative affect and craving. The occurrence of dreams with drugs did not decrease significantly over the five weeks. The crack users reported higher occurrence of dreams with crack than alcoholics and opioids. The specifically dream about drug use was related to negative emotions.

Reid and Simeon (2001). evaluated patients who dream of crack can remain abstinent for a longer period. Christo and Franey (1996), however, studying a group of multiple drugs dependents, found that a high frequency of dreams can be an important factor for relapse. There are few published data on dream for crack users, thus, the present study aims to assess the association between the dream of the crack and the presence of craving for this substance in dependent patients admitted for detoxification.

Method

It is a clinical study, analytical, transversal type.

Was selected 51 inpatients admitted for a detoxification treatment in a public drug treatment facility.

The sample was composed by crack/cocaine dependents patients by CID-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) criteria, male, with a minimum degree of schooling of the fourth grade of Elementary School, between 18 and 65 years of age. The last consumption of crack should be in 24 hours prior to the day of admittance so that there could be a control in relation to the days of abstinence.

The crack should be the preferred drug of the patient, since it is rare to find users of crack/ cocaine that do not use more than one psychoactive substance. The assessed subjects could not be disoriented self and allo-psychically, present psychotic symptoms or other symptoms that would alter performance in tests.

The following instruments were applied:

1.3.1 Socio-demographic data sheet: designed to define the socio-demographic profile of the sample, identifying characteristics that may be important to better evaluate the subject and verified data referring to the consumption of the psychoactive substances.

1.3.2 Mini-Mental State Examination – Mini-Mental State Examination: MMSE (Folstein and Mchugh, 1975) is a very useful trial test in a clinical exam of a patient. It has the goal of assessing the cognitive state, with a score of 25 out of the total 30 points suggests commitment, and under 20 points indicates, definitely, that there is cognitive impairment (Kaplan and Sadock, 2007). It was used, in this study, to exclude patients with cognitive impairment from the sample.

1.3.3 Cocaine Craving Questionnaire Brief (Sussner et.al., 2006): consists of 10 questions with a likert scale of 7 points that goes from "completely disagree" to &ldquo completely agree". The internal consistency of the CCQ-Brief is strong (α = .90). The score of the CCQ-B is obtained by adding the points of all of the questions. We used, in this study, the Brazilian Version Adapted for Crack, published by Araujo et.al. (2010). The Brazilian version, in psychometric validation, distributed itself into two Factors. Factor 1 represents the construct craving and Factor 2, the lack of control in use of crack. The scale can be assessed from the total score (with questions 4 and 7 inverted adding them to the rest), from the points of Factor 1 (sum of all of the questions except for 4 and 7), and from Factor 2 (sum of questions 4 and 7 inverted). The points for cuts of the total number of points are: minimum craving between 0 to 11; mild craving between 12 to 16; moderate craving between 17 to 22; and intense craving for 23 or more points. For Factor 1 it is 0 – 7 minimum craving, from 8 to 9, mild, from 10 to 11 moderate, and 12 or more, intense, and, from Factor 2 it´s 0 to 2 minimum lack of craving control, 3 to 4 mild, 5 to 6 moderate, and 7 or more, intense (Araujo et.al., 2011).

1.3.4 Visual-Analogic Scale for assessing cocaine / crack craving at the moment (EAV): It consists of a 10 centimeter line from 0 to 10 that aims to measure the intensity of craving for crack, with 0 meaning "no craving" and 10 "much craving." This scale has been used in several studies (Pedroso et.al., 2014; Zeni & Araujo, 2011; Santos, Rocha, & Araujo, 2014; Balbinot, Araujo, & Santos, 2015; Maciel, Tractenberg, Viola, Araújo, & Grassi-Oliveira, 2015).

1.3.5 Visual-Analogic Scale for assessing motivation to interrupt the use of crack at the moment (EAV): It consists of a 10 centimeter line from 0 to 10 that aims to measure the intensity of motivation to interrupt the use of crack, with 0 meaning "no motivation" and 10 "much motivation" (Velasquez, Crouch, Stephens, & DiClemente, 2015).

1.3.6 Questionnaire structured to assess sleep and dreams adapted from Araujo et.al. (2008) – It consists of 19 objective questions that refer to sleep and dreams in the first three days of admittance.

The committee of Ethics of the São Pedro Psychiatric Hospital (Porto Alegre / RS) approved this study. All patients, before of the entering in this study, completed the consent form and clarified.

Each patient was referred, between the third and seventh days of abstinence, individually, to a room where he was made an assessment interview and fill out a sheet with identification data. After it was done the Mini-Mental State Examination. Patients who did not meet any exclusion criteria were finally included in the sample, and to, at this time, applied the CCQ-B, and EAV for assess the craving and the Readiness Ruler for Change and the questionnaire of sleep and dreams, both referring to the first 3 days of hospitalization.

Information collected in this study was organized in the "Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Program" (SPSS) version 17.0 Database. The statistical tests used were the Descriptive for an exploratory analysis of the data and, for inferential analysis, the Chi-Square Test, the Mann-Whitney Test for independent samples, and the Linear Regression. The level of significance used as a parameter was equal to 5%.

Results

The sample consisted of 51 patients, male and admitted in a specialized unit for chemical dependency in a public psychiatric hospital. Age of the patients ranged from 18 to 47 years. The mean age was 28 years (DP= 6.3). Schooling found among the patients of the sample was of 4 to 14 years studied, with a mean of 7 years (DP=2.6). Regarding marital status, 30 patients reported being single (58.8%), 13 married (25.5%) and 7 divorced (13.7%).

Apart from using crack, 37 patients (72%) used alcohol up to 30 days before admittance and 48 patients (94%) claimed to have used tobacco in less than 1 month. When these patients were asked about inhaled marijuana and cocaine, 22 patients reported use of the first substance (43%) and 12 reported consumption of the second (23%), also in a period of 30 days. Out of the total of the sample (n=51), 17 subjects were addicted to alcohol (33%), 26 to marijuana (51%), and 49 (96.1%) to tobacco; 20 were abusers of alcohol (39.2%) and 7 were of marijuana (13.7%).

The age at first use of crack was of 21.88 years (DP=5.78; 14-38), the mean of consumed crack, in grams (g), per week was of 18.8 g (DP=16.88; 2-100) and the last consumption had a mean of 5.37 days (DP=1.09; 4-7).

The CCQ-B questionnaire had the following results for craving classification: 0% showing minimum craving (n=0), 3.9% with mild craving (n=2), 45,1% with moderate craving (n=23), and 51% with strong craving (n=26). The overall mean of points in the CCQ-B was of 25.08 points – strong craving (DP=5.97; 15-45). In Factor 1 related to craving itself, the mean was of 12.61 points – strong craving (DP=6.12; 8-35), and in Factor 2, regarding perception of lack of control in the use of crack, the mean was of 12.47 points – strong lack of control (DP=2.55; 2-13).

The mean for scores in the visual-analogic scale for assessing cocaine / crack at the moment of the interview was 1.27 (DP=1.99; 0-10), on a scale from 0 to 10. The visualanalogic scale for assessing motivation to interrupt the use of crack at the moment of the interview, was of 9.18 (DP=2.04; 0-10), on a scale from 0 to 10. In both scales, the higher the score, the higher the value of the researched variable (craving and motivation).

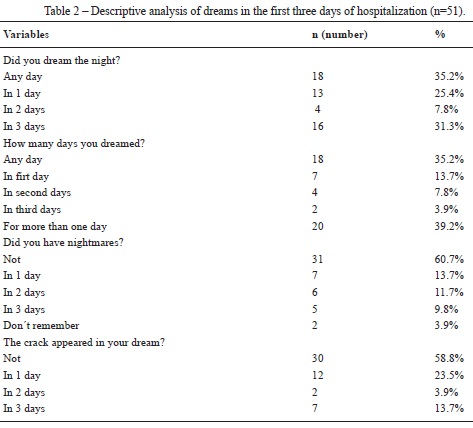

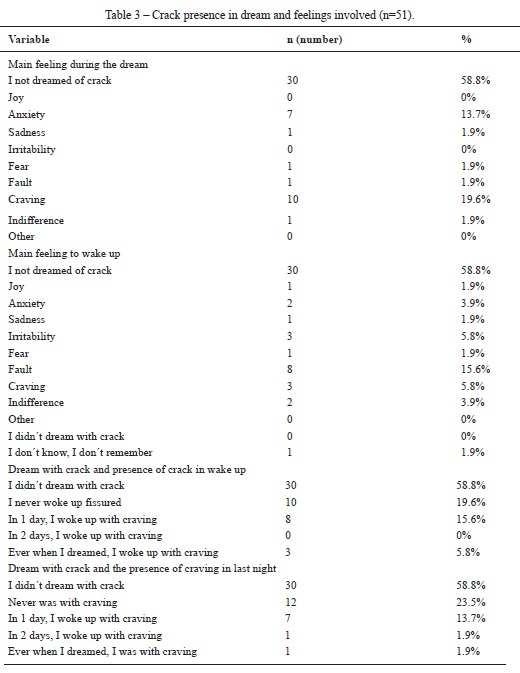

In Tables 1 and 2, the descriptive analysis of sleep and dreams of patients in the first three days of admittance are shown, respectively. In Table 3 are summarized the main feelings during sleep and after you wake up the patients who dreamt of crack.

When separated from the total sample those patients who dreamed of the crack, and analyzed the perception that they had the craving that show at wake up, it was found that 52.4% reported not having agreed craving (n=11). By repeating this operation with respect to the perception of craving presented the night before the dream of the crack, we got the result that 61.9% judged not presented craving (n=13) and 38.1% (n=8) had craving.

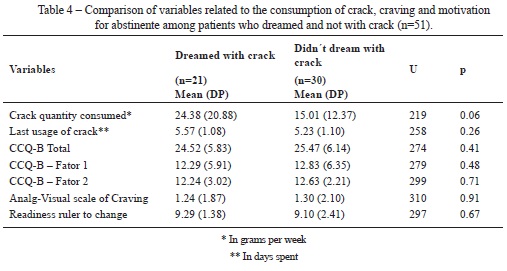

According to the Mann-Whitney Test, subjects that dreamed or did not dream about crack were compared (for statistical analysis, the only individual that did not remember was included in the group that did not dream about crack) in relation to the variable craving and motivation to interrupt the use of crack. The results are shown in Table 4.

The chi-square test was used to assess whether have dreamed of the crack three days before admission, during the consumption phase of this substance, would be associated with the appearance so this same theme in dreams during the current hospitalization, which was no confirmed (x2=6,538; p=0,162). However, the chi-square test confirmed a significant association between the dream and the crack: nightmares in the current hospitalization (x2=15,781; p=0,003) and have multiple awakenings in the middle phase of sleep (x2=11,555; p=0,009).

Discussion

The main question raised by this study is whether there is an association between the presence of dreams with the "crack content" and an increase in craving in admitted patients. The data on this association is very controversial in literature (Araujo et.al., 2008; Beck et.al., 1999; Johnson, 2001; Reid & Simeon, 2001; Yee et.al., 2004; Gillispie, n.d.; Christo & Franey, 1996). Out of the sample studied, 21 of the 51 patients reported having dreamt about crack during the period of the first three days of admittance, which was a high rate as observed in other studies with cocaine addicts (Reid & Simeon, 2001; Yee et.al., 2004). However, the fact of having dreamt of this substance was not associated with an increase in craving, a result similar like that obtained by Yee et.al. (2004) and contrary seconded by Tanguay et.al. (2015).

Another important point of this study was the high score for craving by the patients, from CCQ-B (the overall points, factor 1 and 2), but, in contrast to the low marker in the EVA for assess the desire. This discrepancy may be due to the low sensitivity of EAV – due to having a single item – to measure the craving construct (Araujo et.al., 2011; Araujo et.al., 2008) or by the fact that patients desire confused with the intention of using the substance.

Specifically on the high craving score presented by the subjects assessed through the CCQ-B, and also the high score for lack of control, it becomes evident the need to look at this situation. It seems that this phenomenon reflects the initial period of detoxication, and reinforces the existence of the need for some cases, from the use of hospitalization to start the treatment. The strong craving for crack in admitted patients was also found in a study of Balbinot & Araujo (2012).

Reinforcing previous studies (Weddington et.al., 1990), the quality of sleep of these patients was considered worse in the initial stage, and, although more than half of the sample did not have more of an awakening in the middle phase, a greater number of nighttime awakenings were associated with dreamt of the crack. This same association was found the study by Balbinot & Araujo (2012).

As the occurrence of awakenings during the intermediate stage of sleep facilitates there is a redemption of dreams – because of its content be stored in recent memory (Schredl, 1999; Araujo et.al., 2008) – could be explained the high number of patients who had a dream during hospitalization, which, including, had a higher frequency compared to the period prior to hospitalization. The report of nightmares was uncommon among patients as in the study of Schredl (1999), however was associated with the dream of crack, which is inferred to be due to the facto of the sample being of patients with high average in the EAV to assess the motivation to change addictive behavior and considers aversive have this kind of dream.

Although de 38.1% have presented craving the night before the dream of the crack and 47.6% of patients agreed with craving, this was not considered the main feeling after by patients wake up from this dream. The most common feelings reported, after the dream of waking up with the crack were in descending order: relief, guilt and irritability. It was observed, moreover, that during the dream about this substance, the craving was feeling better informed by patients, followed by anxiety. The dream about drug was associated with negative affect had already been described in the literature (Tanguay et.al., 2015) and, in this case, can with already hypothesized, have been motivated by the profile of the sample to abstinence.

Nevertheless, a high percentage of subjects with craving presence were observed on waking. The knowledge of this aspect has extreme relevance for the subjects that work in the chemical dependence because it implies the need of the knowledge strategies and therapeutic tools. Among the possible therapeutic strategies is mainly the control of fissure through cognitive behavioral techniques, such as the use of respiratory relaxation that was successfully employed in a study by Zeni and Araujo (2009).

A limitation of this study, must be noted, is the sample size, it is suggested to perform longitudinal studies with larger sample and that the address of the association between crack use and the dream of this substance, so they can be best described therapeutic strategies when patients reported that dream in clinical practice.

Conclusion

This study found that dream of the crack is a common behavior in the first three days of hospitalization addict crack / cocaine. However found no association between the presence of dreams with the crack content and craving, even patients taking presents a level of intense craving.

References

Araujo, R. B., Castro, M. D. G. T. D., Pedroso, R. S., Santos, P. L. D., Leite, L., Rocha, M. R. D., & Marques, A. C. P. R. (2011). Validação psicométrica do cocaine craving questionnaire-brief-versão brasileira adaptada para o crack para dependentes hospitalizados. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 60(4), 233-239. [ Links ]

Araujo, R. B., Oliveira, M. D. S., Pedroso, R. S., Miguel, A. C., & Castro, M. D. G. T. D. (2008). Craving e dependência química: conceito, avaliação e tratamento. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 57(1), 57-63. [ Links ]

Araujo, R. B., Pedroso, R. S., & Castro, M. D. G. T. D. (2010). Adaptação transcultural para o idioma português do Cocaine Craving Questionnaire-Brief. Archives of clinical psychiatry, 37(5), 195-198. [ Links ]

Bachtold, L. (1999). Os sonhos na terapia comportamental. Interação em Psicologia, 3(1), 21-34. [ Links ]

Balbinot, A. D., & Araujo, R. B. (2012). Análise do perfil de dependentes de crack em internação hospitalar. Saúde e Pesquisa, 5(3), 471-480. [ Links ]

Balbinot, A. D., Araujo, R. B., & Santos, P. L. (2015). Variação na frequência cardíaca e intensidade do craving durante a exposição a estímulo em dependentes de crack. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 16(3), 23-33. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Wright, F. D., Newman, C. F., & Liese, B. S. (1999). Terapia cognitiva de las drogodependencias. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Bosque, J. D., Fuentes Mairena, A., Bruno Díaz, D., Espínola, M., González García, N., Loredo Abdalá, A., & Sánchez Huesca, R. (2014). La cocaína: consumo y consecuencias. Salud mental, 37(5), 381-389. [ Links ]

Christo, G., & Franey, C. (1996). Addicts drug-related dreams: their frequency and relationship to six-month outcomes. Substance Use & Misuse, 31(1), 1-15. [ Links ]

Colace C. (2014). Drug dreams: clinical and research implications of dreams about drugs in drug-addicted patients. London: Darnac Book. [ Links ]

Delitti, M., & Wielenska, R. C. (1999). Relato de sonhos: como utilizá-los na prática da Terapia Comportamental. Sobre comportamento e cognição, 6, 195-210. [ Links ]

Desseilles, M., Dang-Vu, T. T., Sterpenich, V., & Schwartz, S. (2011). Cognitive and emotional processes during dreaming: a neuroimaging view. Consciousness and cognition, 20(4), 998-1008. [ Links ]

Duailibi, L. B., Ribeiro, M., & Laranjeira, R. (2008). Profile of cocaine and crack users in Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 24, 545-557. [ Links ]

Ferreira Filho, O. F., Turchi, M. D., Laranjeira, R., & Castelo, A. (2003). Perfil sociodemográfico e de padrões de uso entre dependentes de cocaína hospitalizados. Revista de Saúde Pública, 37(6), 751-759. [ Links ]

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research, 12(3), 189-198. [ Links ]

Gillispie C. (n.d.) The Function of Drug-Using Dreams in Addiction Recovery. [ Links ]

Goyal, S., Kaushal, J., Gupta, M. C., Verma S. (2013). Drugs and dreams. Indian Journal of Clinical Practice, 23(10), 624-627. [ Links ]

Guilhardi, H. J. (1995). Um modelo comportamental de análise de sonhos. Psicoterapia comportamental e cognitiva de transtornos psiquiátricos, 257-268. [ Links ]

Johnson, B. (2001). Drug dreams: a neuropsychoanalytic hypothesis. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 49(1), 75-96. [ Links ]

Kaplan, H. I., & Sadock, B. J. (2007). Compêndio de psiquiatria: ciência do comportamento e psiquiatria clínica. (9 ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Kilts, C. D., Schweitzer, J. B., Quinn, C. K., Gross, R. E., Faber, T. L., Muhammad, F., & Drexler, K. P. (2001). Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Archives of general psychiatry, 58(4), 334-341. [ Links ]

Knapp, P., Luz, E., Baldisserotto, G., & Rangè, B. (2001). Terapia cognitiva no tratamento da dependência química. In B. Rangè (Org.), Psicoterapias cognitivocomportamentais: um diálogo com a psiquiatria. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Kober, H., & Mell, M. M. (2015). Neural mechanisms underlying craving and the regulation of craving. In: Wilson SJ (ed.). Handbook on the Cognitive Neuroscience of Addiction. Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford. [ Links ]

Maciel, L. Z., Tractenberg, S. G., Viola, T. W., Araújo, R. B., & Grassi-Oliveira, R. (2015). Craving e dependência de crack: diferenças entre os gêneros. Revista de Psicologia Argumento, 33(81), 258-265. [ Links ]

Mendelson, J. H., & Mello, N. K. (1996). Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(15), 965-972. [ Links ]

Pedroso, R. S., de Castro, M. D. G. T., dos Santos, P. L., Polese, G. P., Balbinot, A. D., Fischer, V. J., & Araujo, R. B. (2014). Validação psicométrica do marijuana craving questionnaire-short form–versão Brasil. Clinical & Biomedical Research, 34(4).

Reid, S. D., & Simeon, D. T. (2001). Progression of dreams of crack cocaine abusers as a predictor of treatment outcome: A preliminary report. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 189(12), 854-857. [ Links ]

Santos, M. P. D., Rocha, M. R. D., & Araujo, R. B. (2014). O uso da técnica cognitiva substituição por imagem positiva no manejo do craving em dependentes de crack. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 63(2), 121-126. [ Links ]

Schredl, M. (1999). Dream recall in patients with primary alcoholism after acute withdrawal. Sleep and Hypnosis, 63(2), 121-126. [ Links ]

Sussner, B. D., Smelson, D. A., Rodrigues, S., Kline, A., Losonczy, M., & Ziedonis, D.(2006). The validity and reliability of a brief measure of cocaine craving. Drug and alcohol dependence, 83(3), 233-237. [ Links ]

Tanguay, H., Zadra, A., Good, D., & Leri, F. (2015). Relationship Between Drug Dreams, Affect, and Craving During Treatment for Substance Dependence. Journal of addiction medicine, 9(2), 123-129. [ Links ]

Velasquez, M. M., Crouch, C., Stephens, N. S., & DiClemente, C. C. (2015). Group treatment for substance abuse: A stages-of-change therapy manual. Guilford Publications. [ Links ]

Weddington, W. W., Brown, B. S., Haertzen, C. A., Cone, E. J., Dax, E. M., Herning, R. I., & Michaelson, B. S. (1990). Changes in mood, craving, and sleep during short-term abstinence reported by male cocaine addicts: a controlled, residential study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47(9), 861-868. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (1993). Classificação de transtornos mentais e de comportamento da CID-10: descrições clínicas e diretrizes diagnósticas. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Yee, T., Perantie, D. C., Dhanani, N., & Brown, E. S. (2004). Drug dreams in outpatients with bipolar disorder and cocaine dependence. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 192(3), 238-242. [ Links ]

Zeni, T. C. D., & Araujo, R. B. (2009). O relaxamento respiratório no manejo do craving e dos sintomas de ansiedade em dependentes de crack. Revista de Psiquiatria do Rio Grande do Sul, 31(2), 116-119. [ Links ]

Zeni, T. C., & Araujo, R. B. (2011). Relação entre o craving por tabaco e o craving por crack em pacientes internados para desintoxicação. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 60(1), 28-33. [ Links ]

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

E-mail:adbalbinot@gmail.com

Recebido em outubro de 2016

Aprovado em março de 2017

1 Natália Vidal Scarparo Sório: Psiquiatra.

2 Carolina Silva Schiefelbein: Psiquiatra.

3 Alexandre Dido Balbinot: Educador Físico, Mestre em Saúde Coletiva (UNISINOS/CAPES), Especialista em Saúde Mental Coletiva (ESP/HPSP), Especialista em Avaliação e Treinamento Físico (ESEF/UFRGS).

4 Paola Lucena dos Santos: Psicóloga e doutoranda em Psicologia (Universidade de Coimbra).

5 Renata Brasil Araujo: Doutora em Psicologia (PUCRS) e Coordenadora dos Programas de Dependência Química e Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental do Hospital Psiquiátrico São Pedro.