Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

versão impressa ISSN 1413-294Xversão On-line ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.24 no.1 Natal jan./mar. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20190011

DOI: 10.22491/1678-4669.20190011

DOSSIER

“PPGPSI-UFRN 20 YEARS: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF RESEARCH AND POSTGRADUATION IN PSYCHOLOGY”

In search of the hyphen: thirty-five years of Environmental Psychology in Rio Grande do Norte

Em busca do hífen: trinta e cinco anos de Psicologia Ambiental no Rio Grande do Norte

En busca del guión: treinta y cinco años de Psicología Ambiental en Rio Grande do Norte

José Q. PinheiroI; Gleice Virgínia Medeiros de Azambuja ElaliII; Fernanda Fernandes GurgelIII; Raquel Farias DinizIV; Tadeu Mattos FariasV; Enric PolVI

IUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

IIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

IIIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

IVUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

VUniversidade Federal de Goiás

VIUniversidad de Barcelona

ABSTRACT

We present a historical and theoretical-methodological panorama of the studies by Grupo de Estudos Pessoa-Ambiente (People-Environment Research Group, GEPA) and their inclusion in the context of environmental psychology. The authors expressed the theoretical-methodological diversity of the area, presented here in terms of the psychological aspects of the relationships between people, climate change and renewable energy sources, underscoring the invisibility and instantaneity of energy; the psychology-sustainability interface, which investigates the psychosocial dimensions of pro-ecological and pro-environmental behaviors; rurality, denoting the scarcity of instrumental and theoretical perspectives that bring psychology and the sociocultural specificities observed closer together; cities, in which studies reveal the tension between the capitalist production of space and the right to the city; and daily settings, which focus on housing, schools and open areas, proposing concepts such as a socioenvironmental image and psychological accessibility. We conclude by showing the connection between group activity and the stresses, developments and challenges faced by the field at the global level.

Keywords: environmental psychology; sustainability, urban environments; rural environments.

RESUMO

Apresentamos um panorama histórico e teórico-metodológico dos estudos do Grupo de Estudos Pessoa-Ambiente (GEPA) e sua inserção no contexto da psicologia ambiental. O grupo tem expressado a diversidade teórico-metodológica da área, apresentada aqui sob os eixos: aspectos psicológicos nas relações entre pessoas, mudança climática e fontes renováveis de energia, destacando-se a invisibilidade da energia e a instantaneidade; interface psicologia-sustentabilidade, que investiga dimensões psicossociais dos comportamentos pró-ecológicos e a pró-ambientalidade; ruralidades, denotando-se a escassez de instrumentais e perspectivas teóricas que promovam aproximação entre psicologia e especificidades socioculturais observadas; cidades, cujos estudos evidenciam a tensão entre a produção capitalista do espaço e direito à cidade; e ambientes cotidianos, que focaliza habitações, escolas e áreas livres, e propõe conceitos como imagem socioambiental e acessibilidade psicológica. Finaliza-se mostrando conexão entre a atividade do grupo e as tensões, desenvolvimentos e desafios do campo em nível global.

Palavras-chave: psicologia ambiental; sustentabilidade; ambientes urbanos; ambientes rurais.

RESUMEN

Presentamos un panorama histórico y teórico-metodológico de los estudios del Grupo de Estudos Pessoa-Ambiente (GEPA) y su inserción en el contexto de la psicología ambiental. El grupo ha expresado la diversidad teórico-metodológica del área, presentada aquí bajo los siguientes ejes: aspectos psicológicos en las relaciones entre personas, cambio climático y fuentes renovables de energía, destacándose la invisibilidad de la energía y la instantaneidad; la interfaz psicología-sostenibilidad, cuyos estudios investigan dimensiones psicosociales del comportamiento pro-ecologico y la pro-ambientalidad; ruralidades, observando la escasez de los instrumentales y perspectivas teóricas que promuevan acercamiento entre psicología y especificidades socioculturales de esos ambientes; ciudades, que han sido estudiadas evidenciando la tensión entre la producción capitalista del espacio y derecho a la ciudad; y los ambientes cotidianos, enfocando viviendas, escuelas y áreas libres, proponiendo conceptos como imagen socio-ambiental y accesibilidad psicológica. Analizamos las conexiones entre nuestras actividades y las tensiones, desarrollos y desafíos del campo a nivel global.

Palavras-clave: psicología ambiental; sostenibilidad; ambientes urbanos; ambiente rural.

We human beings are intrinsically linked to our planet, our environment par excellence, outside of which we would not survive for long (at least with the technology available today). We are born, grow up and die in this environment, from which we derive much of who we are. We move around the environment, seek shelter in it, extract our energy, food and clothing. Thus, we can be described and understood by how we relate to it, a topic that awakens the interest of several areas of knowledge. In Psychology, the subarea aimed at the people-environment relationship is called Environmental Psychology, which studies the psychological aspects of bidirectional relationships between people and the sociophysical environment, in its space-time dimensions.

Ever since its inception in Europe and the United States, Environmental Psychology has proved to be an inductive field, based on ties between basic and applied research, significantly influenced by ecological thinking that started to characterize sectors of human and social sciences in the second half of the 20th century (Pol, 2007). Investigations in the area, which initially focused on the built environment (hospitals, schools and housing), gradually included urban life and natural settings (parks, reserves and the like) and, more recently, issues related to socioenvironmental sustainability, pro-ecological commitment and historical, cultural and political aspects of human experiences in an urban or rural setting (Bonnes & Bonaiuto, 2002; Pol, 2007). In this respect, Gifford (2014) identifies three priorities for contemporary Environmental Psychology: increasing interest in the environment at all levels, from local to global; promoting the role of environmental education in changing people's attitudes and behavior in relation to the environment; and urging professionals linked to environmental planning to consider social planning. According to the author, among the key questions to address are the change in global climate conditions, scarcity of natural resources (water, energy, food, etc.), decline in animal and plant biodiversity, problems of large urban centers (population density, trash, traffic, unhealthy conditions) and environmental pollution (atmospheric, water, soil, visual, noise).

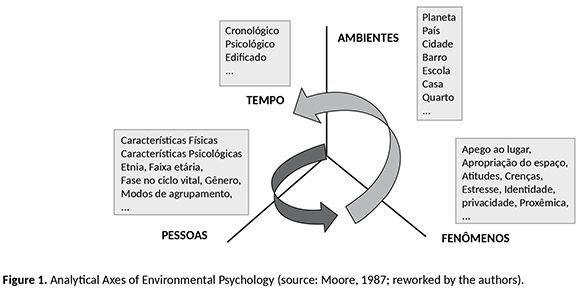

Moore (1987) illustrated the relationship between four analytical axes (Figure 1): people (individuals or groups); physical environments; phenomena generated by the interaction between both; and time.

People are the individuals present in an area, with their unique traits (age, sex, ethnicity, schooling, mobility conditions, and personality) and behavior (effective, individual or group action). The environment represents the set of sociophysical elements present, from the geographic location and bioclimatic traits to form and materials. The phenomena characterize the relationship between people and the environment, corresponding to the psychosocial processes involved. Time represents the sociohistorical condition that acts on the three previous axes, expanding their variability and involving several scales: chronological (the occasion and duration of events), social (rhythm, sequence, constancy, familiarity) and psychological (drives people's actions).

In Brazil, interest in the area emerged in the 1970s, with the translation of books. In 2000, the growth of academic studies and consolidation of graduate courses led to the creation of the Environmental Psychology Working Group (WG) in the National Association of Research and Graduate Programs in Psychology (ANPEPP). Initially, the WG aimed at disseminating the field of research, investing in propagating good practices and concepts essential to its understanding (Günther, Pinheiro, & Guzzo, 2004). Other collections (such as Cavalcante & Elali, 2011; 2018; Pinheiro & Günther, 2008) and special editions followed in national journals, consisting of articles written by Brazilian and foreign researchers, all available free of charge on the internet: a dossier in Estudos de Psicologia (UFRN/Natal; Pinheiro, 1997); a special edition in the same journal (Pinheiro, 2003) and another in Psico (PUCRS/Porto Alegre; Campos, & Bomfim, 2014).

In addition to these collections, a number of individual articles written by members of the WG have been published in national and international journals.

In Rio Grande do Norte, in the Graduate Psychology Program, Environmental Psychology was represented by Grupo de Estudos Pessoa-Ambiente (People-Environment Research Group, GEPA), whose professors researched, lectured and advised in undergraduate and graduate courses (Master's and Doctorate). Since the mid 1980s (the first course was taught by J. Q. Pinheiro, in 1983), GEPA has focused on teaching and researching in the area of human-environmental relations, in its psychological, social and ecological dimensions. In general terms, its aim is to develop the area theoretically and methodologically, as a discipline in Psychology (Environmental Psychology), or inter/multi/transdisciplinary field of studies and interventions.

Authors in the area of people-environment relationships (represented in the expression P-E) typically value one side over the other. In other words, for architects, for example, the environment assumes the first plane (figure) and people are in the background as secondary elements that are casually present in that space (p ← E), whereas psychologists concentrate on people (P → e). However, it is important to underscore that the hyphen (–) itself, the link between the parts, should be the element to investigate, since, through its presence and action indicates that both sides are part of a whole that continuously divides and becomes whole again (Pinheiro & Elali, 2010). Thus, to emphasize our interest in the hyphen, we have aimed at creating a common language and encouraging pursuit of the people-environment binomial (P – E) as the object of shared study, in order to focus on the P-E relation itself (Elali & Pinheiro, 2003), as twice underscored in the name of the group: Grupo de Estudos Pessoa-Ambiente (People-Environment Research Group, GEPA).

An important resource to cope with the difficulties of conceptual and disciplinary integration in the area of people-environment relationships is the multimethod strategy, a methodological response that, despite the inherent operational dilemmas, enables scientific consistency and professional fulfilment (Brewer & Hunter, 2006; Günther, Elali, & Pinheiro, 2008). In addition to incorporating different languages, it also facilitates the interplay between scientists, appliers of this knowledge and users of the environment or community involved. In general, socially relevant objects of study are also complex enough to justify combining two or more data collection and analysis methods. This practice enriches the investigation, especially when it counterbalances complementary aspects of the phenomenon, for example, integrating information on people with information on environments and space, as well as time (Günther, Elali, & Pinheiro, 2011).

Next, we present lines of research we are currently focusing on: renewable sources of energy and climate change; sustainability, pro-ecological commitment and environmental care; urban/city environment, ruralities; and people in daily settings.

Renewable sources of energy and Climate Change

These two topics are discussed together because they are parts of the same dilemma faced by our civilization at the start of a new century. The relationship between them is well illustrated by the image on the cover of the third issue of the First National Assessment Report on Climate Change (Bustamante & Rovere, 2014), aimed at mitigating climate change. The cover shows a series of photovoltaic solar panels, demonstrating that renewable sources of energy (RSEs) are an important low carbon footprint resource, and one of the primary means of preventing climate change (CC). At the same time, since they are dependent on climate conditions, RSEs are potentially subject to the impacts of the very phenomenon they intend to prevent (Rosa, 2008).

As a result of the various studies and investigations that our research group have conducted on these topics, two clear psychological constructs have emerged: the invisibility (Oliveira, 2017) and instantaneity of energy, so characteristic of our contemporary life.

Although intensely present in our daily life, energy goes largely unnoticed in the constant use that we make of technology, being socially perceived as a commodity, with no relation that explicitly connects it to its types of generation (Stern & Aronson, 1984). Illustrating this idea, in a study that applied word associations, we could not use "energia eólica" ("wind energy" in Portuguese) as stimulus, since we found that it was only a label; as such, we selected "energia do vento" (energy from the wind), to more clearly indicate to respondents the type of energy we were discussing.

On one hand, this lack of awareness makes it difficult to assess the degree of dependence of our civilization on fossil fuel energy, the main culprit responsible for greenhouse gases; on the other, it hampers our evaluating the scenario of possible renewable sources of energy, as an alternative to promote ecologically more equitable and sustainable lifestyles. Added to this are the economic and political interests associated with fossil fuels, which make it very difficult to solve climate change (CC).

Instantaneity, in turn, freezes time, transforming it "into a succession of ever-present moments" (Nicolaci-da-Costa, 2011, p. 605). In addition to contributing to the invisibility of energy, it is an important obstacle to perceiving CC and engaging people in its mitigation. In another recent study, in addition to confirming the occurrence of spatial optimism bias, we also found optimism bias for the time scale of the present moment (Pinheiro, Cavalcanti, & Barros, 2018), demonstrating a rigid time perspective in an absolute, individualist and hurried present (Pinheiro, 2012).

There is comfort in the growing, albeit very gradual, presence of the social sciences, including Psychology, in the energy transition scenario (e.g., Lenoir-Improta, Devine-Wright, Pinheiro, & Schweizer-Ries, 2017; Socioenergie, s/d; Sovacool, 2014), including articles and study groups in Portuguese, in some cases in joint research in this multidisciplinary interface (e.g., Delicado, 2015; Rovere, Rosa, Dowbor, & Sachs, 2012). Analogically, Psychology has also conducted studies on CC and accumulated a brief history of contributions to the area (e.g., Clayton et al., 2015; Koger, Leslie, & Hayes, 2011).

Sustainability, Pro-Ecological Commitment and Environmental Care

With the popularization of debates on environmental problems and the harmful impacts of human activities on the environment in the late 1970s, environmental psychology focused on understanding psychosocial aspects and explaining human behavior as part of what can be considered a "human-environmental crisis" (Pinheiro, 1997). In response to the demands of the area, pro-environment knowledge and production and pro-ecological behavior have increased in recent years (Moser, 2018).

From the 1990s, with ample dissemination of the notion of sustainability in Western countries, a number of studies focused on the psychosocial dimensions of sustainable lifestyles (SLSs), defined as a series of effective, conscious and planned measures, resulting in the preservation of human and nonhuman species, considering current and future generations (Corral-Verdugo & Pinheiro, 2004). Thus, the relationships between pro-environment and future time perspective, appreciation of diversity, worldviews, frugal, altruistic and equitable behaviors, emotions, happiness, well-being and quality of life (Corral-Verdugo, 2010) have been explored.

In order to increase knowledge of SLSs, we have developed the notion of pro-ecological commitment (PEC), which encompasses the human-environment relationship, marked by taking responsibility for and interest in environmental issues and engaging in effective environmental care measures (Gurgel & Pinheiro, 2011; Pinheiro & Diniz, 2013). The PEC proposal represents a summary of the indicators used by different scales in internalized systems (ex. attitudes, values and pro-ecological beliefs), as well as the interest in establishing language accessible to different fields of knowledge and environmental education. Another relevant aspect is its diversity, given that PEC is linked to daily choices (ex. consumption, leisure activities), mental and physical health, awareness campaigns and pro-social relations, as well as acknowledging the barriers and habits that hamper environmental care (Diniz & Pinheiro, 2017).

In the course of developing the notion of PEC, we adopted the term environmental care. In this respect, we asked people directly about their environmental care, and to describe the effective actions that express this care (ex. trash disposal, water and electricity conservation, etc.), thereby decreasing the social desirability bias (Diniz & Pinheiro, 2014; Pinheiro & Diniz, 2013).

The results of the studies conducted by our research group are in line with the findings of national and international literature and the Psychology of Sustainability (Pol, 2007). However, we underscore the innovative potential of these studies in terms of epistemological guidance, with the adoption of critical perspectives, as well as inductive, qualitative and mixed methodologies that enable analyses of implementation processes and in-depth assessment of the phenomena investigated.

Ruralities

Despite maintaining certain rural characteristics since its origin, 84.4% of Brazil's population lives in urban areas (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2011), following the worldwide trend in which cities are "the natural habitat of a large part of the human species in our time" (Fernández-Ramírez, 2010, p. 242). While urban areas are highly valued as a synonym of quality of life and technological development, rural regions are seen as backward and bucolic and should follow the development model of cities. In fact, one should not consider a single rural concept, opposite to and disconnected from its urban counterpart. By "ruralities" we mean multiple forms of insertion and existence of people in the countryside, traditional communities, those near water bodies (riverside dwellers, fishermen), in forests and other territories (Brandemburg, 2010).

In hegemonic fashion, Psychology has focused on aspects of human experience in cities, neglecting the rural context. During its development, Environmental Psychology has considered the environment, whether natural or built, as a relevant element in the phenomena under study. However, it ignores ruralities as environments (Mendéz, 2015; Moser, 2018), and when it recognizes them at all, they are considered merely agricultural. However, ruralities cannot be viewed only as a scenario where life goes on, but as places of sociabilities where there is a close relationship and juxtaposition between residences, workplaces, neighborhoods/community ties or even the sacred connection with the land.

Instruments and theoretical perspectives that can promote a closer relationship between psychology and rurality studies and their sociocultural specificities remain scarce (Centro de Referência Técnica em Psicologia e Políticas Públicas [CREPOP], 2013). Nevertheless, there is research on the topic in Brazil and Latin America (Calegare & Higuchi, 2016; Landini, 2015). GEPA has also investigated ruralities, initially without significant awareness of convergence, through studies on emotional ties to places in fishing communities in the state of Rio Grande do Norte and elsewhere (César, 2013; Farias, 2017; Lima, 2012) or those on rural recovery in the urban context, such as in permaculture practices (Diniz & Araújo, 2018). Given the awareness of ruralities, a line of research has been implemented to conduct the first studies on the emotional connection between organic food producers and their land in rural contexts (Pinheiro, 2019) and the socioenvironmental aspects of drought in the life of family farmers in the semiarid region of Northeastern Brazil (Gurgel, 2016).

Despite the fact that such investigations are recent , rurality studies provide elements regarding the psychosocial and affective aspects inherent to people-environment relationships, as well as the rural-urban interface, not as opposition or hierarchy, but as interdependent zones in the context of (non) sustainability of the behaviors of contemporary life. Thus, it seems to signal a "new" space for Environmental Psychology interventions and studies.

Urban/Cities

With the series of lectures entitled "The Metropolis and Mental Life", Georg Simmel (2005) symbolized the intellectual tradition that emerged at the end of the 19th century: reflecting on the subjective effects of life in large modern cities. Since then, different authors have compared a "negative" concept of cities (a tradition that Simmel would be a part of) with a "positive" one (Fernández-Ramírez, 2010). The first group includes studies on the consequences of high population density, pollution, stress, inequality, stimulus overload, fear and violence, among others. An optimistic attitude, in turn, centers on opportunities and diverse activities in cities, social stimulation and meeting with others, as well as the scientific, technological and cultural development potential of cities (Páramo, 2017).

In addition to these topics, the urban transformations in recent decades have promoted the emergence of new categorizations that seek to understand contemporary urban dynamics, which indicate the path of cities in the capitalism that exported industrial activities and absorbed specialized service companies, particularly in the financial and informatics sectors. This led to the development of spectacularized urbanization, aimed at selling cities on a global level, in addition to the present proliferation of non-places (Augé, 1994). The global impacts of this dynamic on the geography of peripheral capitalist cities were studied in depth by Milton Santos (2006). These new cities are also interpreted in terms of conflicts and disputes by the occupation and significance of public places (Di Masso, Dixon, & Pol, 2011).

Most studies in our group that adopted the urban setting as a space to investigate, did so on a smaller scale, such as those described further on. Studies were conducted on the impact of megaevents, more specifically, the 2014 World Cup, held in Brazil, on the relationship between people and cities, based on the dynamics of urban space transformation (Farias, Gurgel, & Diniz, 2015; Farias, Gurgel, Diniz, & Elali, 2017), interpreting cities and their functionality in reproducing the type of capitalist production and megaevents as transformation catalyzers that foster this form of sociability.

The counterpoint to this dynamic is the right to the city (Lefebvre, 2001), which became the object of group studies, especially in interventions aimed at reappropriating public spaces and urban social movements (Farias & Diniz, 2018). These groups and movements promote this dynamic and enable another type of urban life, such as the National Movement for Homeless People (Farias & Diniz, 2019). In this respect, group studies occupy a historic perspective, neither negative, nor positive, which views the city as a complex product of human activity, boosted by alienating trends, but also a source of stress and resistance that opens new historical possibilities for other experiences. This introduces a historical-social framework into human-urban reflections, resulting in ontoepistemological and theoretical challenges that require new discussions both within and outside psychology.

People in their Daily Environments

In everyday environments, the geographic scale of investigations and the concepts used in their framework change slightly from those conducted to date, with a focus on issues and places related to the origin of Environmental Psychology. From this perspective, studies focus on people's experiences with the built environment and the search for physically and psychically healthy spaces (individually or collectively).

Corroborating the notion of "thinking globally, acting locally" (World Commission on Environment and Development [WCED], 1987), we understand that people will only become involved with large scale events through knowledge of their daily experiences, and the peculiarities and demands of the environment in which they live. In other words, environmental awareness occurs from a micro to macro scale: from understanding and commitment to the rooms and buildings in which we live day to day (architecture), to understanding and commitment to the city, country, continent or planet (broader environment). This idea is grounded in multiple sources, which, over time, has reaffirmed maxims such as "paint your village and you will paint the whole world" (Tolstoy) or "what is most personal is most universal" (Rogers).

In this respect, we have focused on habitational environments, schools and open areas (squares and parks), applying concepts such as perception and environmental cognition, space appropriation, place attachment, wayfinding, accessibility and environmental docility, used to clarify concrete situations (as support for interventions or the process of understanding the question under discussion).

Among these studies is the investigation "socioenvironmental image of neighborhoods" (Cesar, 2013; Elali, 2007; Góes, 2011), which reinforces the role of the social dimension in forming a mental image of the environment (Lynch, 1960/2012). Thus, the analytical categories of this author (path, landmark, edge, node, and district), in addition to the physical characteristics of the place, are understood as the fruits of social construction and important elements of the environmental memory of a population, contributing to the legability of the space.

In addition, we investigated the school as an institution, in terms of the behavior of the educational group (Elali, 2003; Fernandes, 2006) and its relationships with the community/neighborhood (Oliveira, Costa, & Elali, 2018), which we call intra and extra-mural relationships (Elali, 2011) and that broaden the debate on the concept of school environment.

In regard to open urban areas, investigations conducted by Vilaça (2008), Liberalino (2011) and Silva (2014) demonstrate the role of parks, squares and sidewalks in the dynamics of daily life and in restoring the physical and psychic equilibrium of city dwellers.

We also underscore studies on environmental accessibility, understood as facilitating the coming and going of everyone, particularly those with mobility problems. In this field, we highlight the concept of psychological accessibility (Elali, Araújo, & Pinheiro, 2010) and the study of the environmental docility conditions of the elderly (Viegas, Silva, & Elali, 2014#RIA37) and those with disabilities.

Final considerations

Up to this point, we have reviewed the most relevant lines of research of GEPA.

We have attempted to demonstrate and provide answers to new challenges without forgetting the origins of our discipline. This is not merely a historicist vocation, but also helps us to understand the meaning of our work and proposals, and even our disciplinary identity.

Why do we use the term "environmental", if we are referring mainly to the interplay between people, habitats and cities? Would "ecological" sensitivity, focused on deteriorating ecosystems (contamination, loss of biodiversity, etc.) rather than emphasizing the conditioning elements of behavior, be a "late conversion"? Mey and Günther (2015) underscore the early contributions of the German ecologists-biologists Ernst Haeckel and Jakob von Uexküll to understanding this apparent contradiction. The key is in the difference that Uexküll makes between the meanings of Umwelt, whose translations refer to both the "environment" and the "ecosystem", which helps understand and justify the "legitimacy" of the "names" or denominations that Environmental Psychology has adopted over time. In addition, it explains and legitimizes how to deal with future challenges, considering the two main areas of stress and development in Environmental Psychology in recent years, namely, sustainability and sustainable development on one hand, and the city as a symbol of urban life, on the other, in addition to rural habitats, frequently forgotten, as we have seen.

In the "origins" of Environmental Psychology, in the 1960s, its main object in North America and Europe was the built environment. This led to the name Architectural Psychology (Canter, 1970), later changed to "Environmental Psychology". To this we must add the so-called Ecological Psychology of Barker and Wright (1948), considered the "precursor" of Environmental Psychology. And once again the apparent contradiction emerges: does Baker study behavior in built environments, because he calls it "ecological"? We have already presented the conceptual matrices between Uexküll's Umwelt and the difficult and inaccurate translations to other languages. This is what leads Barker to speak of "behavior setting" and not the ecosystem or generically of "environment", consciously or not, but with the subtle influence of Kurt Lewin and the German Umweltpsychologie (Environmental Psychology) that preceded it. Understanding the logical and evolutionary processes of these concepts is easier if we consider Pol's proposal (2006) of four stages of Environmental Psychology: (1) First Birth, or remote origins; (2) American Transition; (3) Architecture Psychology; (4) Environmental Psychology for Sustainability.

These "contradictions" are understood and diluted with the acknowledgement of previous contributions, such as that by Haeckel (20th century), who established the framework of modern ecology and "ecosystem" concepts; and by Uexküll (early 20th century), who developed the different Umwelt matrices, understood as the individual world (for a specific species) in contrast to the environment as the physical generic world (Linask, Magnus, & Kull, 2015). It incorporates a dimension of meaning for self (and for species), making what will later be called "ecosystems" specific and unique and providing us with the keys to find and explain the apparent contradictions mentioned. In 1911, under the influence of Wundt's Wölkersychologie, Willy Hellpach (1924) spoke of Geopsyche, or the influence of climatic and geographic factors in relation to individuals and their surroundings, later adopting Umweltpsychologie, influenced by Uexküll.

If we consider that the built environment is the natural "ecosystem" of the "current" human being, it enables us to understand the legitimacy of speaking about Environmental Psychology when we refer generically to personal relationships (society) and their sociophysical environment. The symbolic dimension of this space, which must inevitably be incorporated, is related to the individual and social construction capacity of "meaning", that is, individual and/or shared meanings (by individuals from a same culture). Thus, the built environment, including the sociophysical space, assumes the role of "ecosystem". As such, Environmental Psychology, known as Architectural Psychology, takes on its entire meaning when it starts to develop as an "Ecological Psychology", which aims to create or "restore" the best conditions for human development.

Less "transformable" elements also act on these denominations, such as natural geography and the climate, as indicated by Hellpach. It is precisely the (in principle) non-conscious transformation of these aspects (physical environment, resources and climate) that presents us with the challenge of approaching and contributing to facing climate change (both mitigating and adapting). Adaptation is also related to transforming and reconstructing the environment, but now with criteria of nature, restoring the "conditions or virtues" of natural ecosystems, in a two-fold initiative that is inevitably technological and behavioral (changes in ways of doing, habits, attitudes and behaviors).

Recent years have seen the emergence of two sensitivities. On one hand, interest in the health dimension as the effect of quality (or loss of quality) of the surroundings, but sometimes neglecting the activities of people, and on the other, the need for nature-based solutions (NBS), reintroducing more or less forcibly natural elements of the habitat (primarily urban) that compensate for the environmental degradation caused by life habits and production modes.

This creates new challenges for environmental psychology. Whether on the health or NBS axis, we once again find proposals and actions aimed at attempting to change people's behavior. These frequently ignore the very nature of human beings as extremely complex and diverse social beings. In addition, if umwelt is specific for each species while simultaneously depending on the characteristics of each ecosystem, every place becomes unique and different. It precludes the universalization of locally adequate, but dysfunctional and even counterproductive solutions, in other contexts. Environmental psychology must not lose its roots and local uniqueness, although the processes that underpin the construction of knowledge and solutions are universal as species processes, which is the responsibility of local research groups.

Balancing ecosystems and the global environment with "natural" criteria to face "climate change" or "global warming" has become one of the current challenges we are attempting to overcome in environmental psychology, making it important to disseminate the indispensable specificity of the discipline. This not only contributes to improving the individual and social behavior of people, but helps establish which means, materials and resources are adequate for a habitat that produces greater well-being (such as Architectural Psychology), with the added awareness that not everything is worthwhile. We cannot aspire to quality of life at any price, that is, we must assess the potential impacts of each decision and each action (which leads us to Environmental Management) as the means, materials and structures that "reestablish" or contribute to reestablishing the environmental balance needed (carbon absorption, and restoration of oxygen, water and biodiversity etc.); and how these measures allow or facilitate (never determine) ecologically responsible behaviors.

However, in addition to doing this, we must also explain that it is not simply a matter of the supposed (and arguable) impact of scientific articles on the academic world, but a real effect on people and society, which includes and goes beyond what is considered "transfer". In a world dominated by so-called new intelligent technologies (TIC, Smart Cities, etc.), communication processes became more relevant than ever. This is a new (or renewed) challenge for environmental psychology. As Festinger showed us many years ago, information alone is not enough to change our behavior. We are resistant to change and we generally adapt our thinking (or attitudes) to our behaviors, in order to reduce cognitive dissonance. Human beings are more rationalizers than rational. They search for rational arguments that sustain their position and filter, ignore or deny those that contradict it. But the smart world we are building conforms to algorithms that, as sophisticated as they are, always follow a sequence of simple linear causality (which we human beings call "rationality"). However, human behavior will always be unpredictable, emotional, influenced by the presence of others and NOT rationally changeable.

Environmental Psychology will continue to contribute positively, since, as mentioned at the start, we are intrinsically linked to our planet, our environment par excellence, outside of which we would not survive for long (at least with the technology available today).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte and its Graduate Program in Psychology (PPgPsi), which contributed to this presentation at different times and in different ways.

References

Augé, M. (1994). Não-lugares: introdução a uma antropologia da supermodernidade. Campinas: Papirus. [ Links ]

Barker, R., & Wright, H. (1948). Psychological ecology and the problem of psychological development. Child Development, 20, 131-143. [ Links ]

Bonnes, M. & Bonaiuto, M. (2002). Environmental Psychology: from spatial-physical environment to sustainable development. In R. B. Bechtel & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology (2a ed., pp. 28-54). Nova York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Brandemburg, A. (2010). Do rural tradicional ao rural socioambiental. Ambiente e Sociedade, 13(2), 417-428. doi: 10.1590/S1414-753X2010000200013 [ Links ]

Brewer, J., & Hunter, A. (2006). Foundations of multimethod research: synthesizing styles. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Bustamante, M. M. C., & Rovere, E. L. L. (Eds.). (2014). Mitigação das mudanças climáticas - Primeiro Relatório da Avaliação Nacional sobre Mudanças Climáticas (Vol. 3). Rio de Janeiro: Painel Brasileiro de Mudanças Climáticas. [ Links ]

Calegare, M. G. A., & Higuchi, M. I. G. (2016). Nos interiores da Amazônia: leituras psicossocias. Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Campos, C. B., & Bomfim, Z. A. C. (2014). Psicologia Ambiental: revisando, revisitando e ressignificando. Psico, 45(3), 290-291. doi:10.15448/1980-8623.2014.3 [ Links ]

Canter, D. (Ed.). (1970). Architectural Psychology. Proceedings of the conference held in Dalandui in 1969. London: RIBA. [ Links ]

Cavalcante, S., & Elali, G. A. (Eds.). (2011). Temas básicos em Psicologia Ambiental. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Cavalcante, S., & Elali, G. A. (Eds.). (2018). Psicologia Ambiental: conceitos para a leitura das relações pessoa-ambiente. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Centro de Referência Técnica em Psicologia e Políticas Públicas/CREPOP. (2013). Referências técnicas para atuação das(os) psicólogas(os) em questões relativas a terra. Brasília: Conselho Federal de Psicologia. [ Links ]

César, J. A. G. A. (2013). Modificações no ambiente sócio-físico entre 2005 e 2011: a percepção dos moradores de Itapuama, Cabo de Santo Agostinho/PE. Dissertação de Mestrado, PPGAU, UFRN, Natal. [ Links ]

Clayton, S., Devine-Wright, P., Stern, P. C., Whitmarsh, L., Carrico, A., Steg, L., ... Bonnes, M. (2015). Psychological research and global climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), 640-646. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2622 [ Links ]

Corral-Verdugo, V. (2010). Psicología de la sustentabilidad: un análisis de lo que nos hace pro-ecológicos y pro-sociales. Cidade do México: Trillas. [ Links ]

Corral-Verdugo, V., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2004). Aproximaciones al estudio de la conducta sustentable. Medio Ambiente y Comportamiento Humano, 5(1/2), 1-26. [ Links ]

Delicado, A. (Ed.). (2015). Terras de sol e de vento: dinâmicas sociotécnicas e aceitação social das energias renováveis em Portugal. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Di Masso, A., Dixon, J., & Pol, E. (2011). On the contested nature of place: 'Figuera's Well', 'The Hole of Shame' and the ideological struggle over public space in Barcelona. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31, 231-244. [ Links ]

Diniz, R. F., & Araújo, A. M. C. (2018). Permacultura. In. S. Cavalcante, & G. A. Elali (Eds.), Psicologia Ambiental: conceitos para a leitura das relações pessoa-ambiente (pp. 186-196). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Diniz, R. F., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2014). Cuidado ambiental em tempos de sustentabilidade: relação entre compromisso pró-ecológico e orientação de futuro. Psico, 45(3), 387–394. [ Links ]

Diniz, R. F., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2017). Pro-ecological commitment in the words of its practitioners. Paidéia, 27(supl.1), 395-403. (doi:10.1590/1982-432727s1201704) [ Links ]

Elali, G. A. (2003). O ambiente da escola - o ambiente na escola. Estudos de Psicologia, 8(2), 309-319. [ Links ]

Elali, G. A. (2007). Imagem sócio-ambiental de áreas urbanas: um estudo na Ribeira, Natal-RN-Brasil. Psicología para América Latina, 10, 1-18. [ Links ]

Elali, G. A. (2011). Do intramuros ao extramuros: comentários sobre a apropriação dos espaços livres da escola e pela escola. In G. Azevedo, P. A. Rheingantz, & V. Tangari (Eds.), O lugar do pátio escolar no sistema de espaços livres: uso, forma, apropriação (pp. 107-120). Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ/FAU/PROARQ. [ Links ]

Elali, G. A., Araújo, R. G., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2010). Acessibilidade Psicológica: eliminar barreiras 'físicas' não é suficiente. In A. A. R. Prado, M. E. Lopes, & S. W. Ornstein (Eds.), Desenho Universal: caminhos da acessibilidade no Brasil (pp. 117-127). São Paulo: AnnaBlume. [ Links ]

Elali, G. A., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2003). Edificando espaços, enxergando comportamentos: por um projeto arquitetônico centrado na relação pessoa-ambiente. In F. Lara, S. Marques (Eds.), Projetar: desafios e conquistas da pesquisa e do ensino de projeto (pp. 130-144). Rio de Janeiro: EVC. [ Links ]

Farias, T. M. (2017). Afetividade e resistência: vínculo, transformações socioambientais e oposição capital-lugar na cidade de Galinhos-RN. Tese de Doutorado, PPgPsi, UFRN, Natal. [ Links ]

Farias, T. M., & Diniz, R. F. (2018). Cidades neoliberais e direito à cidade: outra visão do urbano para a psicologia. Psicologia Política, 18(42). [ Links ]

Farias, T. M., & Diniz, R. F. (2019). População em situação de rua e direito à cidade: invisibilidade e visibilidade perversa nos usos do espaço urbano. In M. T. Nobre, A. K. A. Amorim, F. C. Medeiros, & A. C. V. Matos (Eds.), Vozes, imagens e resistências nas ruas: a vida pode mais (pp. 34-62). Natal: EDUFRN. [ Links ]

Farias, T. M., Gurgel, F. F., & Diniz, R. F. (2015). Percepção de moradores de uma cidade sede sobre a Copa do Mundo de Futebol 2014. Psico, 46(2), 265-273. [ Links ]

Farias, T. M., Gurgel, F. F., Diniz, R. F., & Elali, G. A. (2017). A copa do mundo 2014 em Natal (RN-Brasil): um estudo sobre a percepção dos moradores. Research, Society and Development, 5(1), 49-76. [ Links ]

Fernandes, O. S. (2006). Crianças no pátio escolar: a utilização dos espaços e o comportamento infantil no recreio. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Fernández-Ramírez, B. (2010). El medio urbano. In J. I. Aragonés & M. Amérigo (Eds.), Psicología Ambiental (3th ed., pp. 241-259). Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

Gifford, R. (2014). Environmental Psychology matters. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 541-579. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115048 [ Links ]

Góes, R. (2011). Imagem sócio-ambiental de Cidade Nova, Natal-RN, por seus moradores. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Günther, H., Elali, G. A., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2008). A abordagem multimétodos em estudos pessoa-ambiente: características, definições e implicações. In J. Q. Pinheiro & H. Günther (Eds.), Métodos de pesquisa nos estudos pessoa-ambiente (pp. 369-396). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Günther, H., Elali, G. A., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2011). Multimétodos. In S. Cavalcante & G. A. Elali (Eds.), Temas básicos em Psicologia Ambiental (pp. 239-249). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Günther, H., Pinheiro, J. Q., & Guzzo, R. S. L. (Eds.). (2004). Psicologia ambiental: entendendo as relações do homem com seu ambiente. Campinas: Alínea. [ Links ]

Gurgel, F. F. (2016). A seca e suas implicações psicossocioambientais na vida de agricultores da região do Trairi/RN. Projeto de pesquisa, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Gurgel, F. F., & Pinheiro, J. Q. (2011). Compromisso pró-ecológico. In S. Cavalcante & G. A. Elali (Eds.), Temas básicos em Psicologia Ambiental (pp. 159-173). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Hellpach, W. (1924). Psychologie der unwelt. In E. Abderhalden (Ed.), Hanbuch der biologischen arbeitsmethoden (pp.109-112). Berlin: Urban & Schwarzenberg. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística − IBGE (2011). Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010. Rio de Janeiro: Autor.

Koger, S. M., Leslie, K. E., & Hayes, E. D. (2011). Climate change: Psychological solutions and strategies for change. Ecopsychology, 3, 227-235. doi: 10.1089/eco.2011.0041 [ Links ]

Landini, F. (2015). Hacia una psicología rural latinoamericana. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (2001). O direito à cidade. São Paulo: Centauro. [ Links ]

Lenoir-Improta, R., Devine-Wright, P., Pinheiro, J. Q., & Schweizer-Ries, P. (2017). Energy issues: psychological aspects. In G. Fleury-Bahi, E. Pol, & O. Navarro (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology and quality of life research (pp. 543-557). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Liberalino, C. C. (2011). Praça: lugar de lazer - relações entre características ambientais e comportamentais na praça Kalina Maia, Natal-RN. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Lima, J. Y. A. (2012). De vilarejo a cidade: identidade de lugar de moradores nativos de Tibau do Sul-RN. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Linask, L., Magnus, R., & Kull, K. (2015). Applying Jakob von Uexküll's Concept of Umwelt to Human Experience and Development. In G. Mey & H. Günther (Eds), The life Space of the Urban Child. Perspectives on Martha Muchow's Classic Study (pp. 175-192). New Brunswick-London: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Lynch, K. (2012). A imagem da cidade. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. (Original work published in 1960) [ Links ]

Mendéz, A. O. (2015). Psicología Ambiental y ruralidad. In F. Landini (Ed.), Hacia una psicología rural latinoamericana (pp. 307-314). Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [ Links ]

Mey, G., & Günther, H. (Eds.). (2015). The life space of the urban child. Perspectives on Martha Muchow's classic study. New Brunswick-London: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Moore, G. (1987). Environment and behavior research in North America: History, developments, and unresolved issues. In D. Stokols & I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology (Vol. 2; pp. 1359-1410). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Moser, G. (2018). Introdução à Psicologia Ambiental: pessoa e ambiente. Campinas: Alínea. [ Links ]

Nicolaci-da-Costa, A. M. (2011). Tudo ao mesmo tempo: realidade ou ilusão? Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 31(3), 602-615. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932011000300012 [ Links ]

Oliveira, L. M. A. N., Costa, L. M. M., & Elali, G. A. (2018). Percepção ambiental de estudantes sobre seu bairro. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 18(2), 445-464. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P. R. S. (2017). A invisibilidade da energia e sua relação com tempo e tecnologia na experiência humana. Relatório Final de Iniciação Científica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Páramo, P. (2017). The city as an environment for urban experiences and the learning of cultural practices. In G. Fleury-Bahi, E. Pol, & O. Navarro (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research (pp. 275-290). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q. (1997). Psicologia Ambiental: a busca de um ambiente melhor. Estudos de Psicologia, 2(2), 377–398. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q. (2003). Psicologia Ambiental: espaços construídos, problemas ambientais, sustentabilidade. Estudos de Psicologia, 8(2), 209-213. Doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2003000200002 [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q. (2012). Time, a slippery challenge. Bulletin of People-Environment Studies, 39, 8-13. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q., Cavalcanti, G. R. C., & Barros, H. C. L. (2018). Mudanças climáticas globais: viés de percepção, tempo e espaço. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 23(3), 282-292. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q., & Diniz, R. F. (2013). Autoavaliação e percepção social do compromisso pró-ecológico: medidas psicológicas e de senso comum. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia, 45(3), 413–422. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q., & Elali, G. A. (2010). Uma caminhada em terras potiguares. In J. Q. Pinheiro & G. A. Elali (Eds.), Inter-Ações Pessoa-Ambiente: nove estudos potiguares (pp. 9-16). Natal: EdUFRN. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, J. Q., & Günther, H. (Eds.). (2008). Métodos de pesquisa nos estudos pessoa-ambiente. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Pinheiro, L. V. S. (2019). Rompendo cercas, construindo saberes: trabalho agroecológico, vivências e (re)siginificações nas relações com o lugar. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Pol, E. (2006). Blueprints for a history of Environmental Psychology (I): From First Birth to American Transition. Medio Ambiente y Comportamiento Humano, 7(2), 95-113. [ Links ]

Pol, E. (2007). Blueprints for a history of Environmental Psychology (II): from Architectural Psychology to the challenge of sustainability. Medio Ambiente y Comportamiento Humano, 8(1/2), 1-28. [ Links ]

Pol, E. (2006). Blueprints for a history of Environmental Psychology (I): From first birth to American transition. Medio Ambiente y Comportamiento Humano, 7(2), 95-113. Retrieved from https://mach.webs.ull.es/PDFS/Vol7_2/Vol7_2_e.pdf [ Links ]

Rosa, L. P. (2008). Apresentação. In R. Schaeffer, A. S. Szklo, A. F. P. Lucena, R. R. Souza, B. S. M. C. Borba, I. V. L. Costa, A. O. Pereira Júnior, & S. H. F. Cunha (Eds.), Mudanças climáticas e segurança energética no Brasil [Sumário Executivo]. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, COOPE. Retrieved from http://mudancasclimaticas.cptec.inpe.br/~rmclima/pdfs/destaques/CLIMA_E_SEGURANCA-EnERGETICA_FINAL.pdf

Rovere, E. L., Rosa, L. P., Dowbor, L., & Sachs, I. (2012). Energias renováveis no Brasil: desafios e oportunidades. São Paulo: Núcleo de Estudos do Futuro, PUC-SP. [ Links ]

Santos, M. (2006). A natureza do espaço: técnica e tempo, razão e emoção. São Paulo: EDUSP. [ Links ]

Silva, E. A. R. (2014). Interação social e envelhecimento ativo: um estudo em duas praças de Natal/RN. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

Simmel, G. (2005). As grandes cidades e a vida do espírito. Mana, 11(2), 577-591. doi: 10.1590/S0104-93132005000200010 [ Links ]

Socioenergie (s/d). Social sciences information on energy mailing list. Retrieved from https://liste.cines.fr/info/socioenergie [ Links ]

Sovacool, B. K. (2014). What are we doing here? Analyzing fifteen years of energy scholarship and proposing a social science research agenda. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 1-29. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2014.02.003 [ Links ]

Stern, P., & Aronson, E. (Eds.). (1984). Energy use: The human dimension. New York: Freeman. [ Links ]

Viegas, C. C. L., Silva, E. A. R., & Elali, G. A. (2014). Um oásis urbano: dois estudos das interações pessoa-ambiente na Praça Kalina Maia, Natal/RN. Psico, 45, 305-316. [ Links ]

Vilaça, L. B. (2008). Comportamento sócio-espacial de pessoas em movimento: um estudo no calçadão da Av. Roberto Freire, Natal. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal. [ Links ]

World Commission on Environment and Development − WCED. (1987). Brundtland Report - Our Common Future. Retrieved from https://pt.scribd.com/doc/ 12906958/ Relatorio-Brundtland-Nosso-Futuro-Comum-Em-Portugues

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia

Caixa Postal 1611

Natal-RN

CEP 59078-970

Tel.: +55 84 33422236

E-mail: pinheirojq@gmail.com

Received in 22.april.19

Revised in 01.july.19

Accepted in 10.dec.19

José Q. Pinheiro, doutor em psicologia ambiental pela Universidade do Arizona, Tucson, Texas, é professor titular na Univerisdade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte.

Gleice Virgínia Medeiros de Azambuja Elali, doutora em estruturas ambientais urbanas pela Universidade de São Paulo (USP), pós-doutora em arquitetura pela Universidade de Lisboa (UL), é professora titular na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. E-mail: gleiceae@gmail.com

Fernanda Fernandes Gurgel, doutora em psicologia social pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, é professora na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. E-mail: fernandafgurgel@hotmail.com

Raquel Farias Diniz, doutora em psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, é professora na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. E-mail: raqueldiniz.ufrn@gmail.com

Tadeu Mattos Faria, doutor em psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, pós-doutor em psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, é pós-doutorando em psicologia na Universidade Federal de Goiás. E-mail: tadeumattos@gmail.com

Enric Pol, doutor em psicologia pela Universidade de Barcelona, é professor de Psicologia Social Aplicada e Psicologia Ambiental, Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade de Barcelona. E-mail: epol@ub.edu

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI