Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

versão impressa ISSN 1413-294Xversão On-line ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.24 no.4 Natal out./dez. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20190034

DOI: 10.22491/1678-4669.20190034

PSYCHOBIOLOGY E COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Character strengths and subjective well-being in adolescence

Forças de caráter e o bem-estar subjetivo na adolescência

Fortalezas del carácter y bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia

Denise Martins DamettoI; Ana Paula Porto NoronhaI

IUniversidade São Francisco

ABSTRACT

The relations between character strengths and subjective well-being (SWB) were assessed in 826 high school students, attending public schools in Sao Paulo, Brazil (aged 14 to 18, 60.3% female). This study explored gender and age differences as well. Results revealed significant correlations between gratitude, hope and zest, and SWB, with coefficients between .52 and .56. Girls presented higher averages on integrity, kindness, and beauty. Adolescents with 17 years old showed higher means on love and curiosity, whereas social intelligence and humility indicated higher levels for adolescents with 18 years old. The research data allowed us to verify that character strengths are directly related to aspects of SWB and can be considered important resources for people's happiness.

Keywords: psychological assessment; positive psychology; character; teenager.

RESUMO

As relações entre força de caráter e bem-estar subjetivo (BES) foram avaliadas em 826 estudantes do ensino médio de escolas públicas de São Paulo, Brasil (14 a 18 anos, 60,3% do sexo feminino). Este estudo também explorou diferenças de gênero e idade. Os resultados revelaram correlações significativas entre gratidão, esperança e vitalidade com o BES, com coeficientes entre 0,52 e 0,56. As meninas apresentaram médias mais altas de autenticidade, bondade e apreciação do belo. Adolescentes com 17 anos apresentaram maiores médias de amor e curiosidade, enquanto inteligência social e modéstia indicaram níveis mais altos para adolescentes com 18 anos. Os dados da pesquisa permitiram verificar que as forças de caráter estão diretamente relacionadas aos aspectos do BES e podem ser consideradas recursos importantes para a felicidade das pessoas.

Palavras-chave: avaliação psicológica; psicologia positiva; caráter; adolescente.

RESUMEN

Las relaciones entre las fortalezas de carácter y el bienestar subjetivo se evaluaron en 826 estudiantes de secundaria, que asistían a escuelas públicas en Sao Paulo, Brasil (de 14 a 18 años, 60,3% mujeres). Este estudio también exploró las diferencias de género y edad. Los resultados revelaron correlaciones significativas entre gratitud, la esperanza y la vitalidad, y bienestar subjetivo, con coeficientes entre .52 y .56. Las niñas presentaron promedios más altos en integridad, bondad y la belleza. Los adolescentes con 17 años mostraron mayores medios de amor y curiosidad, mientras que la inteligencia social y la humildad indicaron niveles más altos para los adolescentes con 18 años. Los datos de la encuesta permitieron verificar que las fortalezas del carácter están directamente relacionadas con los aspectos de bienestar subjetivo y pueden ser considerados como recursos importantes para la felicidad de las personas.

Palabras clave: evaluación psicológica; psicología positiva; personaje; adolescente.

The most fundamental principle in the Positive Psychology field concerns the individual's well-being and how much it contributes to happiness. Subjective well-being (SWB) is a scientific concept related to happiness, which implies pleasure or satisfaction with life (Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). Diener, Suh, Lucas and Smith (1999) conceptualized SWB as a widespread phenomenon, including emotional responses and global judgments. Emotional responses correspond to decisions of emotions, and moods called affects, that people make about current situations in their lives. Life satisfaction aims to assess beliefs and thoughts related to life in general, on aspects related to work, leisure, love, health, finances, according to their criteria, not as an external imposition.

In short, SWB is a multidimensional construct that comprises three interrelated components: positive affect and negative affect - the affective components, and life satisfaction - the cognitive component. Positive affect reflects how much a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert, while the negative affect concerns anguish, dissatisfaction, aversive moods such as anger, guilt, displeasure, and fear. Life satisfaction refers to global judgments of life, and it means satisfaction with work, health, marriage, etc. (Diener et al., 1999; Woyciekoski, Natividade, & Hutz, 2014).

Character strengths are directly related to aspects of well-being (Lambert et al., 2015). Therefore, they are considered as important resources for people's SWB (Diener et al., 2003; Diener et al., 1999). As far as character strengths are considered likely to be developed, they have been deemed necessary for the promotion of SWB in individuals, despite being stable over time (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Research has reported that character strengths are understood as protective traits and are defined as positive traits manifested by thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in different degrees (Park & Peterson, 2009; Peterson, Ruch, Beermann, Park, & Seligman, 2007). They are more than only useful tools for adapting to stress or difficult life circumstances. They are essential since they allow for psychological growth and the development of a character formed by moral and cultural values (Compton & Hoffman, 2013; Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004).

Character strengths have been studied worldwide through a model of considerable scientific relevance, the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths, developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004). This model includes 24 character strengths organized into six virtues considered culturally universal: creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, and perspective (Wisdom and Knowledge virtue); bravery, persistence, integrity, and zest (Courage virtue); love, kindness, and social intelligence (Humanity virtue); teamwork, fairness, and leadership (Justice virtue); forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation (Temperance virtue); and beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, and spirituality (Transcendence virtue). To contribute to the evaluation of character strengths, the authors created the Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS), an empirical instrument that measures the construct in adults from 18 years. For the younger population, aged 10 to 17, Peterson and Seligman (2004) developed the Inventory of Strengths for Youth (VIA-Youth).

The positive relationship between character strengths and SWB has been reported in adolescents (Gillham et al., 2011; Grinhauz, 2015; Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Ruch, Weber, Park, & Peterson, 2014; Shoshani & Slone, 2013). Character strengths are an essential component of well-being and can be used in the development and maintenance of happiness since they allow pleasure and other positive experiences (Lambert, Passmore, & Holder, 2015). Studies showed that the character strengths most often correlated with life satisfaction were zest, love, and hope. The character strengths most related to positive affect were zest, love of learning, and hope; and with negative affect was zest. In addition, character strengths appear to increase the positive affect, rather than to decrease negative affects (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Oliveira, Nunes, Legal, & Noronha, 2016). Concerning gender differences, Blanca, Ferragut, Ortiz-Tallo and Bendayan (2018) mention that studies showed that girls score signi?cantly higher on love and kindness. On the other hand, age effects are small in general or do not indicate significant correlations with any of the character strengths (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Ruch et al., 2014).

Understanding the solid relationship between character strengths and SWB in adolescents is important. Both constructs indicate overall wellness and may contribute to the promotion of healthy development across the period of adolescence (Blanca et al., 2018). Higher levels of character strengths may be positively related to self-esteem and perception of competence in adolescents, and negatively associated with depression symptoms, contributing to greater life satisfaction among high-school students (Blanca et al., 2018: Ruch et al., 2014; Shoshani & Slone, 2013).

Studies demonstrated that interventions that increase people's awareness of character strengths might increase life satisfaction and decrease psychological symptoms (Gander, Proyer, Ruch, & Wyss, 2013; Harzer, 2016). This information can help the development of intervention programs based on character strengths, being possible to promote a positive education in schools (Grinhauz, 2015). For example, Lottman, Zawaly and Niemiec (2017) report that identifying and promoting the dominant strengths in early childhood help students to be more aware of their character strengths, understanding more about themselves and their place in the world, and learning how to apply it to their lives as a possibility to thrive. Also, it helps meaningful adults in their life, as parents and teachers, to recognize which character strengths they are most likely to express, and which of them could be optimally nurtured and reinforced.

The present study is relevant as far as it seeks to contribute to the field of Positive Psychology, especially with a sample of adolescents, whose studies are still developing in Brazil. With these factors in mind, the present study assessed character strengths and SWB in Brazilian youth. We had two main goals. First, we wanted to verify the relations between character strengths and SWB in our sample. Second, we wanted to explore mean differences regarding gender and age.

Method

Participants

Participants included 826 high-school students, being 39.7% male and 60.3% female, from five public schools in the countryside of the state of Sao Paulo. The age ranged between 14 and 18 years (M = 15.46, SD = 1.075). Self-reported ethnicities included White (53.7%), Latino/Hispanic/Black African (32.4%), Black (9.3%), Indian (0.9%), and Asian (0.7%).

Instruments

Character Strengths Scale for Youth – CSS-Youth (Dametto & Noronha, in press). The scale was developed based on the VIA, and it consists of 120 items responded on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (nothing like me) to 4 (totally like me). Adolescents must mark a list of sentences that describe thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. An example of an item is "if I study hard enough, I'll get good grades", referring to persistence. The confirmatory factorial analysis allowed the extraction of five factors (Interpersonal strengths, Temperance strengths, Theological strengths, Intellectual and leadership strengths, and Judgment strength). The total scale presented an alpha coefficient of 0.94, indicating good internal consistency.

Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Adolescents (Segabinazi et al., 2012). The scale consists of 28 items; 14 regarding positive affects (PA) and 14, negative affects (NA). The items are composed of adjectives, in which individuals mark a number that indicates how much they feel the described emotions. Each item is rated on a Likert scale, with values corresponding to 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The internal consistency of the scale, assessed by the alpha coefficient, was of .88 for PA and NA, with the commonalities of the items ranging from .23 to .63.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (Zanon, Bardagi, Layous, & Hutz, 2014). This scale refers to the adaptation of the instrument Satisfaction with Life Scale -SWLS (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) for the Brazilian context. It comprises five self-report items, on a 7 point Likert scale, with items corresponding to 1 (totally disagree) and 7 (totally agree), assessing the level of life satisfaction of the individual with his living conditions. The alpha coefficient values (.87 and .86 respectively) indicated good accuracy of the scale.

Procedures

After the Research Ethics Committee of private institution approval, the data collection started with a collective section on students who their parents signed the consent forms. The 18 years old participants signed their authorizations. The adolescents answered the CSS-Youth, Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Adolescents and Satisfaction with Life Scale in groups of up to 40 people in the classroom. The researcher instructed the students to read the questions carefully and to answer them according to their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The students completed the tests in approximate 45 minutes.

Data analysis

To achieve the aims of the present study, we analyzed the scores of the CSS-Youth and the SWB scales using Pearson's correlation. Subsequently, we verified the mean differences (Student's t) between the genders and attested the magnitude using Cohen's d. Also, we examined the mean differences between the participant's ages using the multivariate variance (MANOVA) and the Tukey test differentiation between the groups.

Results

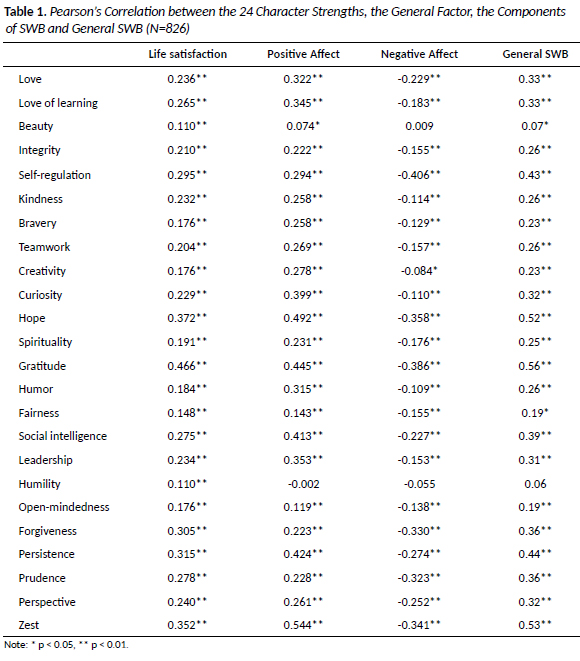

Table 1 shows the Pearson's correlations between the 24 character strengths and SWB. All character strengths were significantly related to life satisfaction, ranging from r = .11 for beauty and humility to r = .46 for gratitude. Positive affect correlated considerably with all strengths except for humility, with magnitudes ranging from r = .07 (beauty) to r = .54 (zest). The negative affect, in turn, was negatively correlated with 22 strengths, from r = -.08 (creativity) to r = -.40 (self-regulation) and only did not present significant results with beauty and humility. The general factor of CSS-Youth with SWB had a significant and moderate correlation of r = .58.

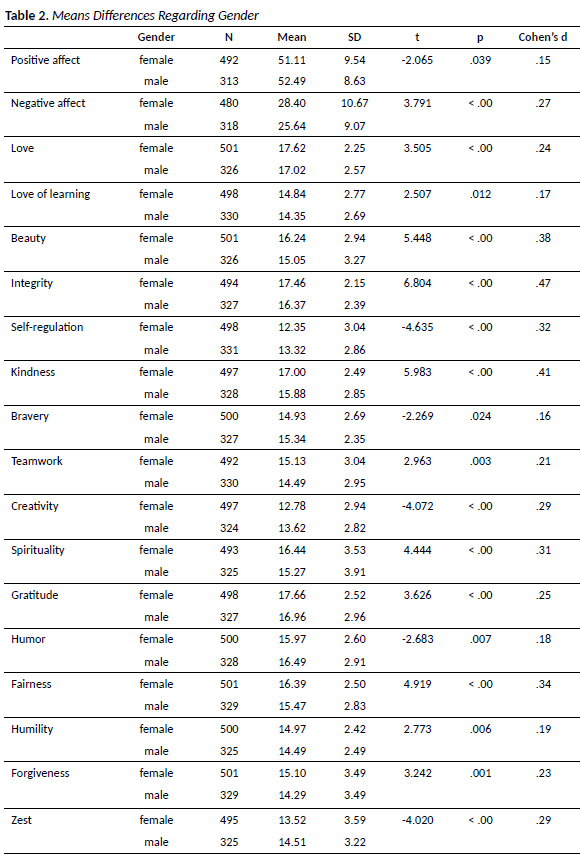

We performed the Student's t test to verify mean differences in character strengths and the components of SWB concerning gender. Also, we used Cohen's d, applying Cohen's (1992) assumptions about the values for the magnitudes, considering them small up to .29, moderate between .30 and .49, and strong from .50. Table 2 below presents this data.

Table 2 indicates only the variables that were significant (p = .05). Observing the Cohen's d, the magnitudes ranged from .15 to .47, ranging from low to moderate. Considering the effect size above .30, girls had the highest averages in beauty, integrity, kindness, spirituality and fairness, and boys in self-regulation strength. Next, we used MANOVA to verify the interaction of the age with the combination of the character strengths and subjective well-being. Table 3 shows the results.

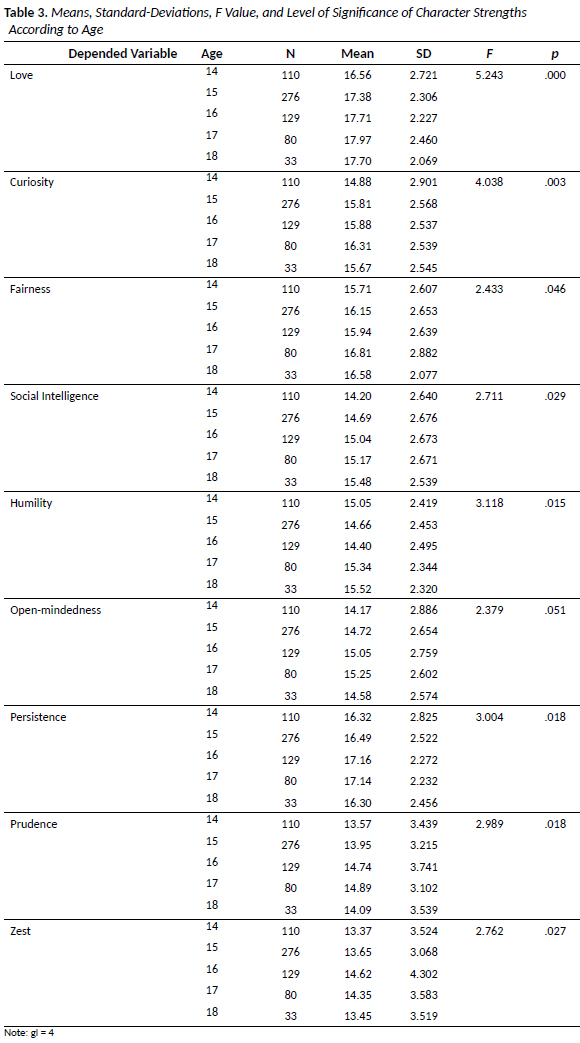

Table 3 shows that the significant values were given only for the character strengths and none of the components of SWB had expressive results. For a better understanding of the data, we performed the Tukey test. The results showed that in four strengths, the organization of the averages occurred in two sets. The older adolescents, with 17 and 18 years, presented the highest averages for love and curiosity. The highest averages were given to individuals of 17 years and on social intelligence and to the adolescents with 18 years on humility.

Discussion

This study aimed to verify the relation between character strengths and subjective well-being in a sample of Brazilian adolescents and to verify mean differences regarding gender and age. Character strengths correlated positively with life satisfaction and positive affect, and negatively with negative affect. These results are consistent with the findings of previous studies that show that both constructs are important in youth's lives (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Noronha & Barbosa, 2016; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Concerning life satisfaction, previous studies showed that the strengths with higher levels of correlation are hope, gratitude, love, and zest (Grinhauz, 2015; Harzer, 2016; Park & Peterson, 2006; Ruch et al. 2014; Van Eeden, Wissing, Dreyer, Park, & Peterson 2008). The results of the present study are partially in agreement with the previous data and the assumptions made. Gratitude, hope, zest, persistence, and forgiveness indicated coefficients higher than .30. Love obtained a low correlation with life satisfaction.

The findings showed that in our sample, the character strengths are positively related to life satisfaction at this stage of adolescence, supporting the idea that character strengths can play a significant role in youth, contributing to a more satisfying life (Blanca et al., 2018; Ruch et al., 2014). The higher the indices of hope, gratitude, zest, love, and persistence, the higher will be life satisfaction. People who expect something good from the future and do their best to achieve it, persisting despite obstacles, are happier, which leads them to have a more fulfilled life. Also, people who have an altruistic attitude, with energy and liveliness, are grateful, and loving, with good social relationships, indicate more life satisfaction (Bailey & Snyder, 2007; Diener & Seliman, 2002; Noronha & Martins, 2016; Park et al., 2004).

In their study, Blanca et al. (2018) highlight hope and love. For example, both character strengths can play an essential role during adolescence. Love can contribute significantly to life satisfaction, especially during early adolescence, when positive relationships with others are important, and new intimate relationships are developed. Hope constrains the person to have an optimistic vision of the future, to implement plans, and achieve them. It is related to SWB as a latent variable measured by self-esteem and life satisfaction. Hope is associated with self-compassion, self-esteem, perceived competence, and adaptive coping strategies. Also, hopeful students show fewer symptoms of depression, achieve greater academic and interpersonal satisfaction, get better grades, and are more motivated and energized by their life goals. In general, there is empirical evidence that hope can protect itself from the effects of adverse events in adolescent life. The authors report that hope is a positive thinking strategic, a vital force in adolescent development, where it may contribute to a protective role.

Regarding the positive affect, zest, hope, gratitude, persistence, and social intelligence presented the highest magnitudes. In their study, Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012) reported the highest correlations were zest, curiosity, love of learning, hope, and perspective, differing from this study in two of the five strengths with the highest coefficients. Considering the disparities found, we should recognize that the samples were from different cultures, which can influence some character strengths. For example, our findings are consistent with the results of Oliveira et al. (2016) study that shows the same strengths significantly correlated with the positive affect on a Brazilian sample. As expected, zest and love of learning indicated significant positive correlations of low magnitude. The more positive emotions a person experiences, the more likely they are to develop their strengths. For instance, positive emotions improve self-development, exploration behaviors, and sociability. Also, it expresses certain information to the individual, including feedback on their general state of life and progress toward goals (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005).

Few studies examined the relations between character strengths and negative affect that we are aware of it. Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012) found negative correlations with hope, curiosity, zest, love, and self-regulation, suggesting that character strengths are negatively related to negative affect, although effect sizes are smaller than those reported for positive affect and life satisfaction. In our study, among the 24 character strengths, self-regulation, gratitude, hope, zest, and forgiveness presented the highest negative correlations with negative affects. As expected, the coefficients were positively correlated with positive affect and negatively correlated with negative affect. The results suggest that character strengths can promote positive outcomes rather than being associated with negative emotions (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Regarding gender, girls are more likely to present higher means in most character strengths (Blanca et al., 2018; Ruch et al., 2014). However, while the findings were statistically significant, the effects sizes were low to moderate. Considering the size of moderate effect and corroborating the data of Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012), Ruch et al. (2014) and Toner et al. (2012) girls stood out on beauty, integrity, kindness, spirituality, and fairness. The boys had the highest averages in self-regulation.

Age did not significantly correlate with any of the character strengths of Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012) and Oliveira et al. (2016) studies. Our findings indicate that love, curiosity, social intelligence, and humility showed significant contributions, which may be related to the fact that character strengths can be learned and developed (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The signi?cant differences found in our sample might be related to maturity since the highest means were for the older individuals aged 17 and 18 years. Our result is consistent with Noronha and Barbosa's (2016) findings. At ages 14 to 17 gratitude, humility, curiosity, kindness, hope, persistence, justice, integrity, humor, open-mindedness, prudence, beauty, love of learning, spirituality, love, social intelligence, bravery, and zest were more endorsed than in the other groups (people aged between 18 and 64).

Although similar studies have been performed before, this study contributes to new data from a Brazilian sample. Research on the analogous relations between these constructs in youth is still scarce in Brazil.

Regarding the limitations of this study, we can mention the sample composition, which included only adolescents attending public schools from a single Brazilian state and, therefore, the results cannot be generalized. Future studies may consider a population with different socioeconomic levels, as well as a greater diversity of regions in the country, besides different cultures. Thus, further studies are needed to obtain additional information, such as how personality traits can affect character strengths and SWB, and other factors that can influence strengths (Ruch et al. 2014; Toner et al., 2012).

We also recommend a more profound address of the development of character strengths and the measurement of SWB in a lifespan, especially concerning the brain transformations and the incomplete ability for emotional self-regulation in early adolescence. Also, further studies could focus on the role gender plays in character strengths and wellbeing in youth, and how these gender differences may change over the lifespan.

Despite these limitations, we hope that this work may have contributed to scientific advancement within Positive Psychology, particularly on revealing which character strengths are most associated with the subjective well-being of adolescents. This data can provide meaningful clues regarding the development of intervention programs based on character strengths in schools (Grinhauz, 2015). For example, Blanca et al. (2018) mention that an intervention based on the strengths of the heart, such as love and hope, can focus on helping students explore, identify, and act toward their own life goals. Similarly, having love as the guide for the intervention may help young people value close relationships with parents and peers and experience more significant support and safer attachments. A qualified education system should emphasize not only the transmission of formal knowledge, but also important areas such as student socialization, community engagement, and basic learning that promote full personal development, including the affective, social, ethical and moral dimensions (Grinhauz, 2015).

References

Bailey, T. C., & Snyder, C. R. (2007). Satisfaction with life and hope: A look at age and marital status. The Psychological Record, 57, 233-240. doi: 10.1007/BF03395574 [ Links ]

Blanca, M. J., Ferragut, M., Ortiz-Tallo, M., & Bendayan, R. (2018). Life satisfaction and character strengths in Spanish early adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1247-1260. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9865-y [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155-159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [ Links ]

Compton, W. C., & Hoffman, E. (2013). Positive Psychology: The science of happiness and flourishing. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Dametto, D. M., & Noronha, A. P. P. (in press). Construction and Validation of the Character Strengths Scale for Youth (CSS-Youth). Paidéia,e2930. doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2930 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well- being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403-425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056 [ Links ]

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13, 80-83. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00415. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Suh. E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276-302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [ Links ]

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Wyss, T. (2013). Strength-based positive interventions: Further evidence on their potential for enhancing well-being and alleviating depression. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1241-1259. doi: 10.1007%2Fs10902-012-9380-0. [ Links ]

Gillham, J., Adams-Deutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., Coulter-Heindl, V., Linkins, M., ... Seligman, M. E. P., (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 31-44. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.536773 [ Links ]

Grinhauz, A. S. (2015). El estudio de las fortalezas del carácter en ni-os: Relaciones con el bien estar psicológico, la deseabilidad social y la personalidad. Psicodebate, 15(1), 43-68. doi: 10.18682/pd.v15i1 [ Links ]

Harzer, C. (2016). The eudaimonics of human strengths: The relations between character strengths and well-being. In J. Vitterso (Ed.), Handbook of eudaimonic well-being (pp. 307-322). New York: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42445-3_20 [ Links ]

Lambert, L., Passmore, H. A, & Holder, M. D. (2015). Foundational frameworks of positive Psychology: Mapping well-being orientations. Canadian Psychology, 56(3), 311-321. doi: 10.1037/cap0000033 [ Links ]

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel Hebrew adaptation of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 41-50. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000089 [ Links ]

Lottman, T., Zawaly, S., & Niemiec, R. M. (2017). Well-being and well-doing: Bringing mindfulness and character strengths to the early childhood classroom and home. In C. Proctor (Ed.), Positive Psychology Interventions in Practice (pp. 83-105). Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-51787-2_6 [ Links ]

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does Happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803-855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2016). Forças e Virtudes: Escala de Forças de caráter. In C. S. Hutz (Ed.), Avaliação em Psicologia Positiva: técnicas e medidas (pp. 21-43). São Paulo: CETEPP. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Martins, D. F. (2016). Associations between character strengths and life satisfaction: A study with college students. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 19(2), 97-103. doi:10.14718/ACP.2016.19.2.5 [ Links ]

Oliveira, C., Nunes, M. F. O., Legal, E. J., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2016). Bem-Estar Subjetivo: estudo de correlação com as forças de caráter. Avaliação Psicológica, 15(2), 177-185. doi: 10.15689/ap.2016.1502.06 [ Links ]

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 891-909. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.011 [ Links ]

Park, N., & Peterson, P. (2009). Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College & Character, 10(4). doi: 10.2202/1940-1639.1042 [ Links ]

Park, N., & Peterson, P., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-619. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748 [ Links ]

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 149-156. doi: 10.1080/17439760701228938 [ Links ]

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Ruch, W., Weber, M., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2014). Character strengths in children and adolescents: Reliability and initial validity of the German Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth (German VIA-Youth). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(1), 57-64. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000169 [ Links ]

Segabinazi, J. D., Zortea, M., Zanon, C., Bandeira, D. R., Giacomoni, C. H., & Hutz, C. S. (2012). Escala de afetos positivos e afetos negativos para adolescentes: adaptação, normatização e evidências de validade. Avaliação Psicológica, 11(1), 1-12. Recuperado de http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712012000100002&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2013). Middle school transition from the strengths perspective: Young adolescents' character strengths, subjective well-being, and school adjustment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1163-1181. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9374-y [ Links ]

Toner, E., Haslam, N., Robinson, J., & Williams, P. (2012). Character strengths and wellbeing in adolescence: Structure and correlates of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Children. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 637-642. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.014 [ Links ]

Van Eeden, C., Wissing, M. P., Dreyer, J., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2008). Validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth (VIA-Youth) among South African learners. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(1), 145-156. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2008.10820181 [ Links ]

Woyciekoski, C., Natividade, J. C., & Hutz, C. S. (2014). As Contribuições da personalidade e dos eventos de vida para o bem-estar subjetivo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 30(4), 401-409. doi: 10.1590/s0102-37722014000400005 [ Links ]

Zanon, C., Bardagi, M. P., Layous K., & Hutz, C. S. (2014). Validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale to Brazilians: Evidences of measurement noninvariance across Brazil and US. Social Indicators Research, 119(1), 443-453. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0478-5 [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Universidade São Francisco - Psicologia

Rua Waldemar César da Silveira

Campinas-SP, Brazil

CEP. 13.045-510

Telefone: (19) 3779-3300

Email: denisedametto@gmail.com

Recepted in 25.aug.17

Revised in 26.sep.19

Accepted in 31.dez.19

Denise Martins Dametto, Doutora em Psicologia pela Universidade São Francisco – USF, Pós-doutora pela University of British – UBC Columbia, é Psicológa atuando com Psicologia Positiva, validação de testes psicológicos e psicometria e consultora na área de Avaliação.

Ana Paula Porto Noronha, Doutora em Psicologia Ciência e Profissão pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas – PUC Campinas e Docente da Universidade São Francisco – USF. Email: ana.noronha@usf.edu.br