Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

Print version ISSN 1413-294XOn-line version ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.25 no.1 Natal Jan./Mar. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20200001

10.22491/1678–4669.20200001

PSYCHOBIOLOGY E COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Developmental dyslexia and executive functions: evidence on main evaluation methods

Dislexia do desenvolvimento e funções executivas: evidências sobre os principais métodos de avaliação

Dislexia del desarrollo y funciones ejecutivas: evidencias sobre los principales métodos de evaluación

Cibele Siebra SoaresI; Amanda GuerraII; Arnaud RoyIII; Izabel HazinIV; Cíntia Salgado AzoniV

IUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

IIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Université d'Angers

IIIUniversité d'Angers

IVUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

VUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

ABSTRACT

In recent years, a growing number of studies have been associating Developmental dyslexia (DD) with alterations in executive functions (EF). However, the literature still hasn't reached a consensus on this subject. This study objective was to carry out a systematic literature review of the most explored functions and neuropsychological instruments for the assessment of EF on children and teenagers with DD, between the years of 2007 and 2017. Seventy–one different instruments for the assessment of EF in individuals with DD were mapped. The most used tests were the Digit Span Task, the Stroop Test and the Tower of London. The most studied EF was working memory. It was concluded that the recent interest in this research field, the wide variety of instruments employed and of EF models adopted hamper the establishment of a consensus on the influence of the diverse aspects of EF on DD.

Keywords: neuropsychological tests; dyslexia; child; adolescent; review.

RESUMO

Nos últimos anos, crescente número de estudos tem associado à Dislexia do Desenvolvimento (DD) a alterações em funções executivas (FE). No entanto, a literatura ainda não apresenta consenso quanto a esta questão. Este estudo teve como objetivo realizar revisão sistemática da literatura, investigando os instrumentos e as funções neuropsicológicas mais exploradas para avaliar as FE em crianças e adolescentes com DD, entre os anos de 2007 e 2017. Foram mapeados 71 instrumentos para avaliar FE em indivíduos com DD. Os testes mais utilizados foram o Digit Span Task, o Stroop Test e o Tower of London. A FE mais estudada foi a memória de trabalho. Conclui–se que o recente interesse neste campo de pesquisa, a grande variedade de instrumentos empregados e de modelos de FE adotados dificulta o estabelecimento de um consenso sobre a influência dos diversos aspectos das FE na DD.

Palavras–chave: testes neuropsicológicos; dislexia; criança; adolescente; revisão.

RESUMEN

En los últimos años, un creciente número de estudios asocian la dislexia del desarrollo (DD) a alteraciones en las funciones ejecutivas (FE). Sin embargo, la literatura aún no ha llegado a un consenso sobre este tema. El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura de las funciones más exploradas y los instrumentos neuropsicológicos más utilizados para la evaluación de las FE en niños y adolescentes con DD, entre los años de 2007 y 2017. Fueron mapeados 71 instrumentos diferentes para la evaluación de EF en individuos con DD. Las pruebas más utilizadas fueron la Tarea de Digit Span, la Prueba de Stroop y la Torre de Londres. La FE más estudiada fue la memoria de trabajo. Se concluyó que el reciente interés en este campo de investigación, la gran variedad de instrumentos empleados y de modelos de FE adoptados dificultan el establecimiento de un consenso sobre la influencia de los diversos aspectos de las EF en la DD.

Palabras clave: pruebas neuropsicológicas; dislexia; niño; adolescente; revisión.

Developmental dyslexia (DD) is a specific learning disorder of neurobiological origin, characterized by disabilities in reading, word decoding and spelling abilities, resulting from a deficit in phonological processing (Luo, Wang, Wu, Zhu, & Zhang, 2013). Such difficulties cannot be explained by neurological damage, intellectual, visual or auditory disabilities, or a precarious educational environment (B. Shaywitz et al., 2001; S. Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005). According to the DSM–5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), these deficits are related to a below–expected academic performance for the intellectual level and chronological age of individuals. However, although DD is largely associated with deficits in phonological structure, a growing number of studies have associated it with impairments in other cognitive aspects, such as executive functions (EF) (Horowitz–Kraus, Toro–Serey, & DiFrancesco, 2015; Moura, Simões, & Pereira, 2014; Varvara, Varuzza, Sorrentino, Vicari, & Menghuini, 2014).

EF constitute a set of higher cognitive abilities that allow the subject to engage in goal–oriented behaviors, performing voluntary, independent, self–organized and goal–directed actions (Elliott, 2003; Gazzaniga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2006). These abilities are especially important in the face of new situations or in circumstances that require adjustment, adaptation or flexibility of behavior to meet the demands of the (Huizinga, Dolan, & van der Molen, 2006). Despite the existence of different definitions, a number of conceptual and operational similarities among researchers agree that EF consists of a multidimensional construct in its essence with more than one individual component or function (Diamond, 2013; Miyake & Friedman, 2012; Miyake et al., 2000). The plurality and interdependence of EF hampers the elaboration of tasks that allow the specific assessment of individual executive components. Thus, this theoretical design suggests that these functions should be assessed considering its multifaceted nature.

The current literature on children's dysexecutive syndromes highlights great variability between executive symptoms and the different clinical conditions (Garcia–Barrera, 2019). Studies with EF and neurological, genetic and neurodevelopmental disorders have been widely discussed, such as in epilepsy (Agah, Asgari–Rad, Ahmadi, Tafakhori, & Aghamollaii, 2017, Type 1 Neurofibromatosis (Pride, Korgaonkar, North, Barton, & Payneac, 2017; Roy et al., 2010, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – TDAH (Graham, 2017; Ter–Stepanian et al., 2017) and Autistic Spectrum Disorder – TEA (Brady et al., 2017; Craig et al., 2016), among others. However, the literature on EF in specific learning disorders, such as dyslexia, is still incipient and controversial (Beneventi, Tønnessen, Ersland, & Hugdahl, 2010; Lima, Salgado, & Ciasca, 2008; Moura et al., 2014; Reiter, Tucha, & Lange, 2005; Walda, van Weerdenburg, Wijnants, & Bosman, 2014).

In most studies, working memory is widely recognized as one of the main processes of EF that is impaired in school–age dyslexics (Bacon, Parmentier, & Barr, 2013; Horowitz–Kraus, 2014). Although there is a relative consensus on the presence of working memory deficits in DD children, studies regarding how other EF components (inhibition, flexibility and planning) affect DD, has not yet reached a consensus. Some studies have found greater impairment in inhibition (Kapoula et al., 2010; Lima et al. 2008), planning (Sesma, Mahone, Levine, Eason, & Cutting, 2009) and cognitive flexibility (Lima et al., 2008; Rodrigues, Barbosa, Piza, Miranda, & Bueno, 2014) in individuals with DD and others have not identified any difference in performance between the DD and typical developmental population.

However, it should be noted that researches comparing the performance of children and adolescents with DD in relation to typical development children do not usually consider the multifaceted nature of EF. This lack of an integrated approach in the executive assessment leads to an incomplete investigation of EF and to a simplistic understanding of the executive deficit in children with DD. In this context, this study aimed to investigate the most used neuropsychological instruments and the most explored EF in children and adolescents with DD, through a systematic literature review.

Method

In order to reach the proposed goal, a systematic literature review was performed in the digital databases Google Scholar, MEDLINE (PubMed), PsycINFO and SciELO. To search the periodicals in these databases, the following English–language descriptors, combined with one another, were used: "developmental dyslexia", "dyslexia", "reading disability" and "executive function". In addition, the descriptors "adult" and "preescholer", also in the English language, were excluded.

The inclusion criteria of the scientific articles in the present review were: reports of researches published between the years 2007 and 2017; articles with language in Portuguese, English and Spanish; researches conducted with children and adolescents in the age group of 6 to 18 years old and articles with digital availability in full. The exclusion criteria adopted were: studies that did not provide sufficient data for the extraction of information on the sample and instruments used and researches that included participants with associated comorbidities (e.g., autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyscalculia, and brain injury). In addition, articles that did not specify the criteria for diagnosis and selection of subjects with DD were excluded. The selection of the articles occurred, initially, from the reading of the title and abstract. The studies that presented content identified with the topic of the review were chosen for the reading in full and subsequent analysis of inclusion in this study.

Results

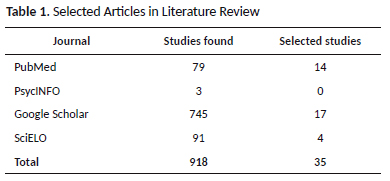

The information related to the search results of the periodicals in the PubMed, PsycINFO, Google Scholar and SciELO databases are presented in Table 1. In total, following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 35 articles were selected to compose this review.

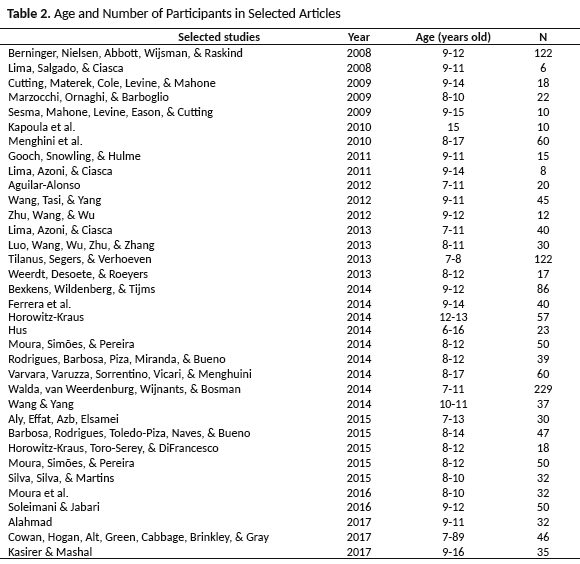

In Table 2, the list of selected articles is described, as well as the data corresponding to the age range and sample size used in each study. It was observed that the minimum age of participants included in the studies was 6 years old and the maximum age was 17 years old. Regarding the sample size, it was identified that the smallest sample size considered was of eight participants. The maximum number of subjects participating in a study was 229.

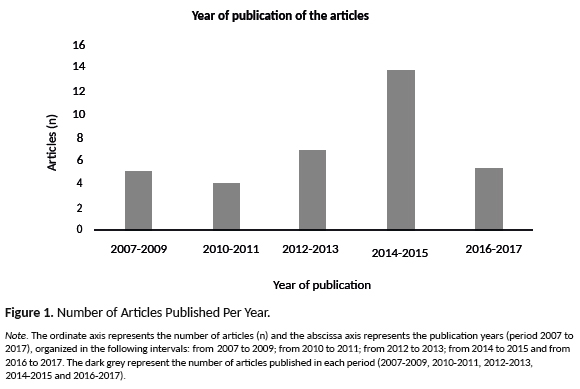

It was observed a lower concentration of publications between 2007 and 2009 (n = 5) and between 2010 and 2011 (n = 4) compared to the period between 2012 and 2013 (n = 7). The largest number of publications, however, was identified between 2014 and 2015 (n = 14), concentrating, during this period, 40% of the publications of the total articles selected (see Figure 1).

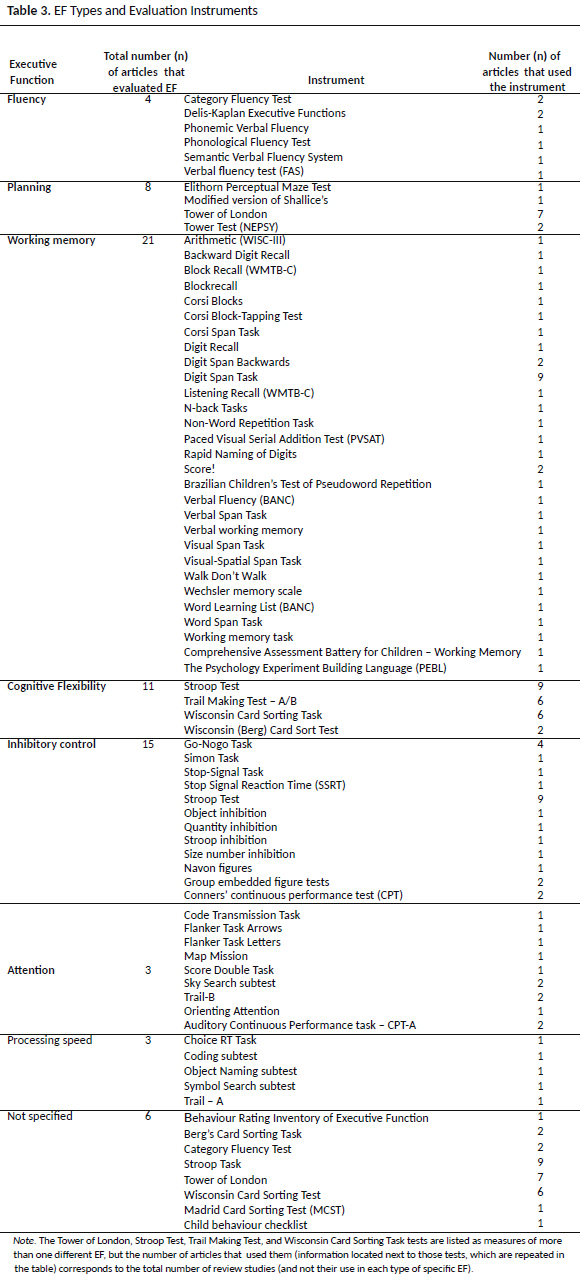

From the results presented in Table 3, it is possible to identify that, in total, 71 different instruments were mapped to evaluate the EF in individuals with DD. These tests were used to measure seven different types of EF, according to the nomenclature used in each article. In this sense, the functions Fluency, Planning, Working Memory, Cognitive Flexibility, Inhibitory Control, Attention and Processing Speed were described as EF. In addition, an "unspecified" category was created to refer to studies that did not explicitly state the EF type evaluated in the research and attributed the tests used to a unified evaluation of executive functioning.

The EF in which the greatest variety of tests or tasks was used for its evaluation was the working memory (n = 29). On the other hand, the cognitive abilities that presented the fewest instruments applied in their evaluations were planning (n = 4) and cognitive flexibility (n = 4).

The tests that had the highest frequency of use in EF evaluations in children and adolescents with DD were the Digit Span Task (n = 9) and Stroop Test (n = 9), followed by Tower of London (n = 7), Trail Making Test – A/B (n = 6) and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (n = 6) and Go–Nogo Task (n = 4).

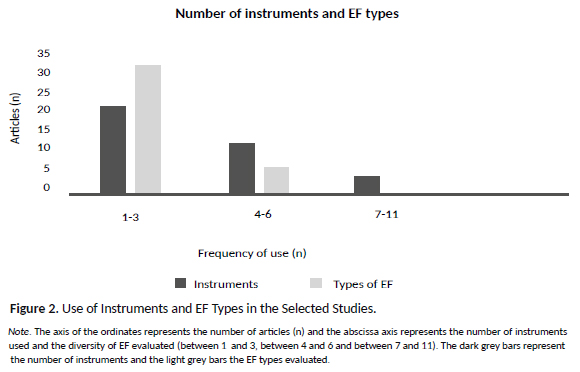

It was also analyzed the way EF are evaluated in the researches, in relation to the number of instruments used and the number of functions identified as EF (already listed in Table 3) (see Figure 2). It was identified that most of the selected studies used only one to three different instruments to evaluate the executive abilities of individuals with DD (n = 20). While only four articles made use of seven or more different evaluation measures in the researches. For the types of EF explored, the vast majority of the selected studies (n = 29) also concentrated the researches on only one or even three abilities attributed to the EF. Only six articles searched between four and six cognitive domains of different EF in subjects with DD.

Discussion

This study aimed to perform a systematic literature review on the main neuropsychological instruments used to evaluate the EF of children and adolescents with DD, as well as the types of EF most studied. Given that the dysexecutive profile of children with DD is still not a consensual theme in the literature, investigations of this topic need to be better explored.

The presence of EF impairment in neurodevelopmental disorders is well established in the literature. However, researches addressing the relationship between this cognitive domain and DD have been gaining momentum only in recent years (Horowitz–Kraus et al., 2015; Moura et al., 2014; Varvara et al., 2014). As observed in the results of this review, although the search for the articles has encompassed the last 10 years, only between the years 2014 and the middle of 2017 were concentrated 54.3% of the selected publications. The number of articles published a year and a half ago, for example, already adds the same amount of publications between the beginning of the year 2007 and the end of the year 2009.

The increase in the number of these publications may be due to the understanding of DD as a multidimensional disorder, in which the development of reading ability is dependent not only on phonological awareness, but on other higher cognitive abilities, such as EF (Horowitz–Kraus, 2014; Sesma et al., 2009). Evidence of EF impairments in DD was obtained through neuroimaging studies, which identified an altered pattern of neural activation in areas of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (involved in EF) and decreased gray matter in individuals affected by this disorder (Horowitz–Kraus et al., 2015).

Thus, a better understanding of the impact of EF impairment on DD is very pertinent, since DD is one of the most frequent learning disorders, affecting approximately 5% to 10% of the general population (Bexkens, Wildenberg, & Tijms, 2014; Horowitz–Kraus, 2014). In addition, the EF impairment to the individuals with DD can have negative consequences not only for the children's school performance, but also in the emotional, social and family environment, influencing daily activities, also having a significant impact on the future professional achievements (Bacon et al., 2013).

EF have been defined in innumerable ways, from models and theories that consider diverse executive aspects. This theoretical variation leads to different methodological choices and different classifications for the same instrument (Malloy–Diniz, Fuentes, Mattos, & Abreu, 2010). In this review, 71 different instruments were mapped to evaluate the EF in individuals with DD to measure seven different EF types according to the nomenclature used in each article. This find indicates a wide divergence between the evaluation methods adopted in this field of research.

Regarding the choice of evaluation measures, the most used tests were the Digit Span Task, Stroop Test, Tower of London, Trail Making Test – A/B and WCST. These data are in agreement with the reference of some tasks considered gold standard for evaluation of EF used in the pediatric population, such as WCST and Tower of London (Hamdan & Pereira, 2009). However, according to Miyake et al. (2000) it is important to consider that, despite the wide acceptance of these tasks as executive functioning measures, construct validities are not well established, since there is a shortage of rigorous theoretical analysis and independent empirical evidence on what these executive tasks actually propose to measure. This lack of clarity of the abilities underlying complex executive tasks is reflected in a proliferation of terms and concepts used to characterize the abilities required to perform a given task in different executive tests.

In this respect, the results of the search performed corroborate this information, pointing out that the WCST, Stroop, Tower of London, Trail Making Test, Conner's Continuous Performance Test (CPT) were categorized heterogeneously by the articles. The Stroop test, for example, was categorized at the same time as a measure of flexibility, of inhibitory control (the most classical function, to which it is linked and the one that obtained a greater frequency of use) and to no specific EF. Likewise, WCST was classified by articles that used it both as a measure of flexibility and as an unspecified measure of EF evaluated. While these suggestions may seem reasonable at an intuitive level, the lack of clarity about what these executive tests really measure may hinder the interpretation of the results by the diversity of factors obtained, which leads to associations that may sometimes seem arbitrary (Miyake et al., 2000). As a consequence, although a wide variety of tests and EF types are being used to study children and adolescents with DD, a theory and the widely accepted means of evaluating this disorder still need to be established (Walda et al., 2014).

Evidence of EF impairments in children and adolescents with DD could be better interpreted if more EF types and more tasks were included by EF types in the studies, as this would increase the validity and accuracy of the results (Moura et al., 2014). However, through the results of the review, it was observed that the vast majority of articles cover at most three different EF in the researches and use up to three different tests for this purpose.

Despite the methodological divergences, the literature has been consistent in describing as one of the main characteristics of DD the deficit in working memory (Luo et al., 2013). Efficient reading is dependent on working memory, as it helps individuals manipulate information in the text, such as remembering previously read words, decoding unknown words, and retrieving information about the semantics of familiar words, and thus forming a coherent representation of the meaning of the material read (Moura et al, 2014; Sesma et al., 2009). The results of this study, for example, indicated that 60% of the articles selected included the evaluation of working memory in individuals with DD. The greatest variety of tests was also used in the evaluation of this function. Other EF that presented the highest frequency of approach among the selected articles were cognitive flexibility (31%) and inhibitory control (43%), reading abilities (Sesma et al., 2009).

Conclusions

Thus, according to the results which met the inclusion criteria of this systematic review, it is possible to conclude that the interest in the investigations of the EF in children and adolescents with DD has been growing considerably. However, the great variety in the instruments used and the models of EF adopted among the researches makes it difficult to establish a consensus regarding the influence of the different aspects of the EF in the DD. In this sense, it is necessary that more researches are carried out in the deepening of the existing theories, with the use of more reliable instruments in the relation between this disorder and the EF.

References

Agah, E., Asgari–Rad, N., Ahmadi, M., Tafakhori, A., & Aghamollaii, V. (2017). Evaluating executive function in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy using the frontal assessment battery. Epilepsy Research, 133, 22–27. doi: 10.1016/J.EPLEPSYRES.2017.03.011 [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ Links ]

Bacon, A., Parmentier, F., & Barr, P. (2013). Visuospatial memory in dyslexia: evidence for strategic deficits. Memory, 21, 189–209.doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.718789 [ Links ]

Beneventi, H., Tønnessen, F., Ersland, L., & Hugdahl, K. (2010). Executive working memory processes in dyslexia: Behavioral and fMRI evidence. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51, 192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467–9450.2010.00808.x [ Links ]

Bexkens, A., Wildenberg W., & Tijms, J. (2014) Rapid automatized naming in childrenwith dyslexia: Is inhibitory control involved? Dyslexia 21, 212–234. doi: 10.1002/dys.1487 [ Links ]

Brady, D. I., Saklofske, D. H., Schwean, V. L., Montgomery, J. M., Thorne, K. J., & McCrimmon, A. W. (2017). Executive functions in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 32(1), 31–43. doi: 10.1177/1088357615609306 [ Links ]

Cowan, N., Hogan, T., Alt, S., Green, S., Cabbage, K., Brinkley, S., & Gray, S. (2017). Short–term memory in childhood dyslexia: Deficient serial order in multiple modalities. Dyslexia, 23(3), 209–233. doi: 10.1002/dys.1557 [ Links ]

Craig, F., Margari, F., Legrottaglie, A. R., Palumbi, R., Giambattista, C., & Margari, L. (2016). A review of executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorder and attention–deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1191–202. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S104620 [ Links ]

Cutting, L., Materek, A., Cole, C., Levine T., & Mahone, M. (2009). Effects of fluency, oral language, and executive function on reading comprehension performance. Annals of Dyslexia, 59(1), 34–54. doi: 10.1007/s11881–009–0022–0. [ Links ]

Czermainski, F. R., Riesgo, R. S., Guimarães, L. S. P., Salles, J. F., & Bosa, C. A. (2014). Executive functions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 24(57), 85–94. doi: 10.1590/1982–43272457201411 [ Links ]

Demetriou, E. A., Lampit, A., Quintana, D. S., Naismith, S. L., Song, Y. J. C., Pye, J. E., ... Guastella, A. J. (2017). Autism spectrum disorders: A meta–analysis of executive function. Molecular Psychiatry, 23, 1198–1204. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.75 [ Links ]

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev–psych–113011–143750 [ Links ]

Dias, N. M. (2009). Avaliação neuropsicológica das funções executivas: tendências desenvolvimentais e evidências de validade de instrumentos. Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. [ Links ]

Elliott, R. (2003). Executive functions and their disorders. British Medical Bulletin, 65, 49–59. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12697616 [ Links ]

Funahashi, S. (2001). Neuronal mechanisms of executive control by the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience Research, 39, 147–165. Retrieved from www.elsevier.com/locate/neures [ Links ]

Garcia–Barrera, M. A. (2019). Unity and diversity of dysexecutive syndromes. In A. Ardila, S. Fatima, & M. Rosselli (Eds), Dysexecutive Syndromes (pp. 3–27). Switzerland: Springer Cham. doi: 10.1007/978–3–030–25077–5_1 [ Links ]

Gazzaniga, M. S., Ivry, R. B., & Mangun, G. R. (2006). Neurociência cognitiva: a biologia da mente (2nd ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Graham, S. (2017). Attention–deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Learning Disabilities (LD), and executive functioning: Recommendations for future research. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 50, 97–101. doi: 10.1016/J.CEDPSYCH.2017.01.001 [ Links ]

Hamdan, A. C., & Pereira, A. P. A. (2009). Avaliação neuropsicológica das funções executivas: considerações metodológicas. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 22(3), 386–393. doi: 10.1590/S0102–79722009000300009 [ Links ]

Horowitz–Kraus, T. (2014). Pinpointing the deficit in executive functions in adolescents with dyslexia performing the wisconsin card sorting test: An ERP study. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(3), 208–223. doi: 10.1177/0022219412453084 [ Links ]

Horowitz–Kraus, T., Toro–Serey, C., & DiFrancesco, M. (2015). Increased resting–state functional connectivity in the cingulo–opercular cognitive–control network after intervention in children with reading difficulties. PLoS One, 10(7), e0133762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133762 [ Links ]

Huizinga, M., Dolan, C. V., & van der Molen, M. W. (2006). Age–related change in executive function: Developmental trends and a latent variable analysis. Neuropsychologia, 44(11), 2017–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.01.010 [ Links ]

Jauregi, J., Arias, C., Vegas, O., Alén, F., Martinez, S., Copet, P., & Thuilleaux, D. (2007). A neuropsychological assessment of frontal cognitive functions in Prader? Willi syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(5), 350–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2788.2006.00883.x [ Links ]

Kapoula, Z., Lê, T., Bonnet, A., Bourtoire, P., Demule, E., Fauvel, C., ... Yang, Q. (2010). Poor Stroop performances in 15–year–old dyslexic teenagers. Experimental Brain Research, 203(2), 419–425. doi: 10.1007/s00221–010–2247–x [ Links ]

Lima, R., Salgado, C., & Ciasca, S. (2008). Desempenho neuropsicológico e fonoaudiológico de crianças com dislexia do desenvolvimento. Revista Psicopedagogia, 25(78), 226–235. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103–84862008000300005&lng=pt&tlng=pt

Luo, Y., Wang, J., Wu, H., Zhu, D., & Zhang, Y. (2013). Working–memory training improves developmental dyslexia in Chinese children. Neural Regeneration Research, 8(5), 452–460. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673–5374.2013.05.009 [ Links ]

Malloy–Diniz, L. F., Fuentes, D., Mattos, P., & Abreu, N. (2010). Avaliação neuropsicológica (1st ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. doi: 10.1177/0963721411429458 [ Links ]

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex Frontal Lobe'' Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [ Links ]

Moura, O., Simões, M., & Pereira, M. (2014). Executive functioning in children with developmental dyslexia. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 28(1), 20–41. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2014.964326 [ Links ]

Pride, N. A., Korgaonkar, M. S., North, K. N., Barton, B., & Payneac, J. M. (2017). The neural basis of deficient response inhibition in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: Evidence from a functional MRI study. Cortex, 93, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/J.CORTEX.2017.04.022 [ Links ]

Reiter, A., Tucha, O., & Lange, K. (2005). Executive functions in children with dyslexia. Dyslexia, 11(2), 116–31. doi: 10.1002/dys.289 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, C., Barbosa, T., Piza, C., Miranda, M., & Bueno, O. (2014). Neuropsychological characteristics of dyslexic children. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 27(3), 539–546. doi: 10.1590/1678–7153.201427315 [ Links ]

Roy, A., Roulin, J., Charbonnier, V., Allain, P., Fasotti, L., Barbarot, S., ... Gall, D. LE. (2010). Executive dysfunction in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: A study of action planning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16(6), 1056–1063. doi: 10.1017/S135561771000086X [ Links ]

Sesma, H., Mahone, E., Levine, T., Eason, S., & Cutting, L. (2009). The contribution of executive skills to reading comprehension. Child Neuropsychology, 15(3), 232–246. doi: 10.1080/09297040802220029 [ Links ]

Shaywitz, B., Shaywitz, S., Pugh, K., Fulbright, R., Mencl, W., Constable, R., ... Gore, J. C. (2001). The neurobiology of dyslexia. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1(4), 291–299. doi: 10.1016/S1566–2772(01)00015–9 [ Links ]

Shaywitz, S., & Shaywitz, B. (2005). Dyslexia (specific reading disability). Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.043 [ Links ]

Ter–Stepanian, M., Grizenko, N., Cornish, K., Talwar, V., Mbekou, V., Schmitz, N., & Joober, R. (2017). Attention and executive function in children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disorders. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(1), 21–30. Retrieved from https://www.cacap–acpea.org/wp–content/uploads/Attention–and–Executive–Function–in–Children–Diagnosed–with–ADHD.pdf [ Links ]

Varvara, P., Varuzza, C., Sorrentino, A., Vicari, S., & Menghuini, D. (2014). Executive functions in developmental dyslexia. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00120 [ Links ]

Walda, S., van Weerdenburg, M., Wijnants, M., & Bosman, A. (2014). Progress in reading and spelling of dyslexic children is not affected by executive functioning. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(2014), 3431–3454. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.013 [ Links ]

Weerdt, F., Desoete, A., & Roeyers, H. (2013). Behavioral inhibition in children with learning disabilities. Research In Developmental Disabilities, 34(6), 1998–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.02.020 [ Links ]

Recepted in 30.may.18

Revised in 01.jun.20

Accepted in 07.jul.20

Cibele Siebra Soares, Mestre em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Endereço para correspondência: Rua Otacílio Nepomuceno, 695. Apto 402 A, Bairro Catolé CEP 58.410–160, Campina Grande – PB. Email: cibelesiebrass@gmail.com

Amanda Guerra, Mestre em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Doutoranda em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) e pela Université d'Angers. Email: adlbguerra@hotmail.com

Arnaud Roy, Doutor em Psicologia pela Université d'Angers, é Professor de Neuropsicologia da criança no Laboratoire de Psychologie des Pays de la Loire, EA4638, Université d'Angers, Faculté des Lettres, Langues et Sciences Humaines, Angers, França, é Coordenador do Centre Référent des Troubles d'Apprentissage e do Centre de Compétence Nantais de Neurofibromatose, CHU de Nantes, Nantes, França. Email: arnaud.roy@univ–angers.fr

Izabel Hazin, Doutora em Psicologia Cognitiva pela Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE) e Pós–Doutora pela Universitè René Descartes – Paris V, é Professora Associada 3 do Departamento de Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Email:izabel.hazin@gmail.com

Cíntia Salgado Azoni, Doutora em Ciências Médicas pela Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) e Pós–Doutora em Ciências Médicas pela Faculdade de Ciências Médicas (UNICAMP), é Professora Adjunta A da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Email: cintiasalgadoazoni@gmail.com