Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

Print version ISSN 1413-294XOn-line version ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.25 no.4 Natal Oct./Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20200046

10.22491/1678-4669.20200046

SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AND MENTAL HEALTH

Development and implementation of a brief chat-based intervention to support mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

Desenvolvimento e implementação de uma intervenção breve via chat para suporte em saúde mental durante a pandemia da COVID-19

Desarrollo e implementación de una intervención breve vía chat para dar apoyo en salud mental durante la pandemia de COVID-19

Henrique Pinto GomideI; Carolina Silva Bandeira de MeloII; Elisa Maria Barbosa de Amorim-RibeiroIII; Joanna Gonçalves de Andrade TostesIV; Lílian Perdigão Caixêta ReisV; Maria Lorena LefebvreVI; Rodrigo LopesVII; Tiago Paz e AlbuquerqueVIII; Yone Gonçalves de MouraIX; Telmo Mota RonzaniX

IUniversidade Federal de Viçosa

IIUniversidade Federal de Viçosa

IIIUniversidade Salgado de Oliveira

IVCentro de Referência em Pesquisa, Intervenção e Avaliação em Álcool e outras Drogas

VUniversidade Federal de Viçosa

VIUniversidad Nacional de Tucumán

VIIUniversidade de Berna

VIIIUniversidade Federal de Viçosa

IXConsultório Particular - Guaratinguetá/SP

XUniversidade Federal de Juiz de Fora

Abstract

This paper presents the development and implementation of a brief chat-based intervention for mental health support toward people suffering from the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil and Argentina. During the development phase, we proposed a protocol that comprised: 1) screening and needs assessment; 2) health education based on active listening techniques; and 3) referral to available materials and crisis services available (e.g., crisis intervention hotlines). In the implementation phase, we recruited and trained 77 volunteers who provide healthcare chat support for users under the supervision of 20 psychologists. In less than two months, we performed 1.107 sessions. We expect that the healthcare chat support might be a valuable resource during the COVID-19 pandemic, although further studies to assess its feasibility and effectiveness are needed.

Keywords: infectious disorders (covid-19); continuing education; mental health; online chat groups.

Resumo

Este artigo apresenta o desenvolvimento e a implementação de uma intervenção breve via chat para suporte em saúde mental voltada para pessoas em sofrimento decorrente do contexto da pandemia de COVID-19, no Brasil e na Argentina. Durante a fase de desenvolvimento, foi proposto um protocolo que inclui: 1) triagem e avaliação de necessidades; 2) educação em saúde com base em técnicas de escuta ativa e 3) encaminhamento de materiais e contatos de serviços especializados ou de urgência disponíveis (ex. linhas diretas de intervenção em crise). Na fase de implementação, foram recrutados e treinados 77 voluntários que oferecem acolhimento em saúde via chat aos usuários sob a supervisão de 20 psicólogos. Em menos de 2 meses, 1.107 intervenções foram realizadas. Espera-se que a intervenção via chat possa ser um recurso valioso durante a pandemia de COVID-19, embora estudos adicionais sejam necessários para avaliar sua viabilidade e sua efetividade.

Palavras-chave: distúrbios infecciosos (covid-19); educação permanente; saúde mental; grupos de chat online.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta el desarrollo e implementación de una intervención breve vía chat para dar apoyo en salud mental destinado a personas que presentan sufrimientos debido al contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19, en Brasil y Argentina. Durante la fase del desarrollo fue propuesto un protocolo que incluye: 1) detección y evaluación de necesidades; 2) educación para la salud basada en técnicas de escucha activa y 3) derivación de materiales y contactos de servicios especializados o de emergencia disponibles (ej. líneas directas de intervención en crisis). En la fase de implementación, fueron reclutados y capacitados 77 voluntarios que ofrecen contención en salud vía chat a los usuarios bajo la supervisión de 20 psicólogos. En menos de 2 meses se realizaron 1.107 intervenciones. Se espera que la intervención vía chat pueda ser un recurso valioso durante la pandemia de COVID-19, aunque se necesitan estudios adicionales para evaluar su viabilidad y efectividad.

Palabras-clave: transtornos infecciosos (covid-19); educación continua; salud mental; grupos de chat en línea.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been one of the most significant challenges for public health in recent decades. Its rapid spreading generated structural impacts in almost all countries. Governments, scientists, and private companies responded to the challenge by developing new methods for preventing cases and treating infections (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020).

Mental health is one of the areas affected by the uncertainties caused by this serious disease, alongside with its severity, secondary impacts (economic and social), and social distancing measures to control the epidemic (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). In this sense, interventions that target population's mental health have been proposed worldwide (e.g., Duan & Zhu, 2020). The WHO emphasizes implementing mental health care services in countries to reduce the impacts caused by COVID-19 (United Nations [UN], 2020).

Guidelines for psychological interventions for natural disasters and emergencies are available in the literature and have guided adaptations to this new situation (Pan american Health Organization [PAHO], n.d.). However, existing challenges caused by the novelty of the disease and the need for social distancing (WHO, 2020b) are added to old challenges, such as difficult access to a face-to-face mental health care network and availability of services in remote places.

Internet-based interventions have strong evidence of effectiveness in reducing barriers to mental health access (Gomide, Martins, & Ronzani, 2013). Although they are not meant to replace face-to-face interventions, they present some advantages, such as their availability for populations that lack access to services (Muñoz, 2010). Internet-based interventions focus mainly on behavior change and symptom improvement (Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, 2010), therefore, such interventions can be recommended (1) when no other type of treatment is available; (2) when patients are waiting for treatment; (3) as a complement to standard treatment (blended treatments); (4) after traditional treatments (e.g., relapse prevention); (5) for patients who are unable to commute to treatment centers due to geographical distance,  physical or financial limitations; (6) for patients who feel stigmatized when seeking treatment; and finally, (7) to extend treatment care to prevention (Muñoz, 2010). During the crisis of COVID-19, such interventions are justified by the orientation of social isolation recommended by health authorities. In Brazil, regulations were approved by the Ministry of Health (Portaria n. 467, 2020) and the Federal Council of Psychology (Resolução n. 4, 2020) to promote access to online mental health interventions.

Chats and written messages are feasible options for delivering online mental health interventions. Hoermann, McCabe, Milne, and Calvo (2017) evaluated their feasibility through a systematic literature review. They found that chat interventions were feasible and showed similar results when compared to face-to-face interventions. Alvarez-Jimenez and collaborators (2020) developed and evaluated the Moderated Online Social Therapy + (MOST+), a platform for interdisciplinary counseling via chat. MOST+ was available for 12 to 25 year-olds with moderate to severe mental health conditions for nine weeks. The service expanded traditional face-to-face services and promoted improvements in clinical and social variables.

Several universities and health centers have begun offering online mental health support in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; support varied by the mean of delivery (i.e., chat, phone, or video), the nature of the interaction agent (i.e., human or bot), and the contact characteristic (i.e., synchronous or asynchronous). Online support typically involves one or more strategies to deal with the restrictions and stress arising from the pandemic, availability of information for daily self-care, self-application of diagnostic instruments, and mapping access to the network of specialized services. Most of these initiatives took place through interdisciplinary efforts established quickly (Agyapong, 2020; Duan & Zhu, 2020; Gould & Hantke, 2020; Ravindran et al., 2020; Sheth et al., 2020; Soklaridis et al., 2020).

Online mental health support is fundamental in Latin America, a culturally diverse region marked by social disparities and barriers to healthcare (Gallegos et al., 2020; Muñoz, 2010, Scholten et al., 2020). Despite earlier developments of online support, there is still a gap regarding structured interventions based on protocols. This article aims to present the development and implementation of a brief mental health care intervention via chat for people struggling with problems caused by social isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil and Argentina.

Description and development of the intervention

This intervention is the result of a cooperation between Brazilian and Argentinian researchers. The international partnership results from a cooperation agreement for training and research between the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), in Brazil, and the National University of Tucumán (UNT), in Argentina. We sought to develop the protocol from a comprehensive perspective, considering similarities and respecting the two countries' specificities (Scholten et al., 2020). The Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Petropolis (CAAE: 30698520.8.1001.5281) approved this research.

We divided the intervention development into the following phases: (1) Development of the clinical protocol; (2) creation of the web platform; (3) selection and organization of support materials and services for referral; (4) definition of the team and their respective functions; and (5) volunteer training.

Clinical Protocol Development

First, we defined our target audience: people aged 18 years and over, dealing with general psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. After that, we reviewed the literature on psychological aid in crisis and emergencies (American Psychological Association [APA], n.d; International Red Cross, 2020; Miranda, 1996; Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses, 2020; PAHO, 2015; Paterson & Eisenberg, 2003), and on the recommendations of the Inter-American Society of Psychology (Gallegos et al.,2020) and global humanitarian services (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2020; PAHO, 2020). We have reviewed material specifically developed for Brazil (FIOCRUZ, 2020).

Then, we organized our protocol around five topics: (1) specific concerns about social aspects (i.e., income, finances, food, and hygiene), (2) specific concerns related to the impact of the disease (i.e., prevention, symptoms, and treatment), (3) mild and moderate symptoms of anxiety (e.g., fear of infection, insecurity, concerns about the future), (4) mild and moderate symptoms of depression and grief (e.g., hopelessness, anhedonia, sadness), and (5) interpersonal problems arising from isolation (i.e., family conflicts, couple conflicts, management of new work formats, such as home-office).

We carried out the protocol development through rounds of discussions within our research team, focusing on the available evidence, adequacy, clarity, and relevance. The discussions followed the methodology of participatory action - planning, developing, and evaluating activities that promote people's active participation (Xavier et al., 2014).

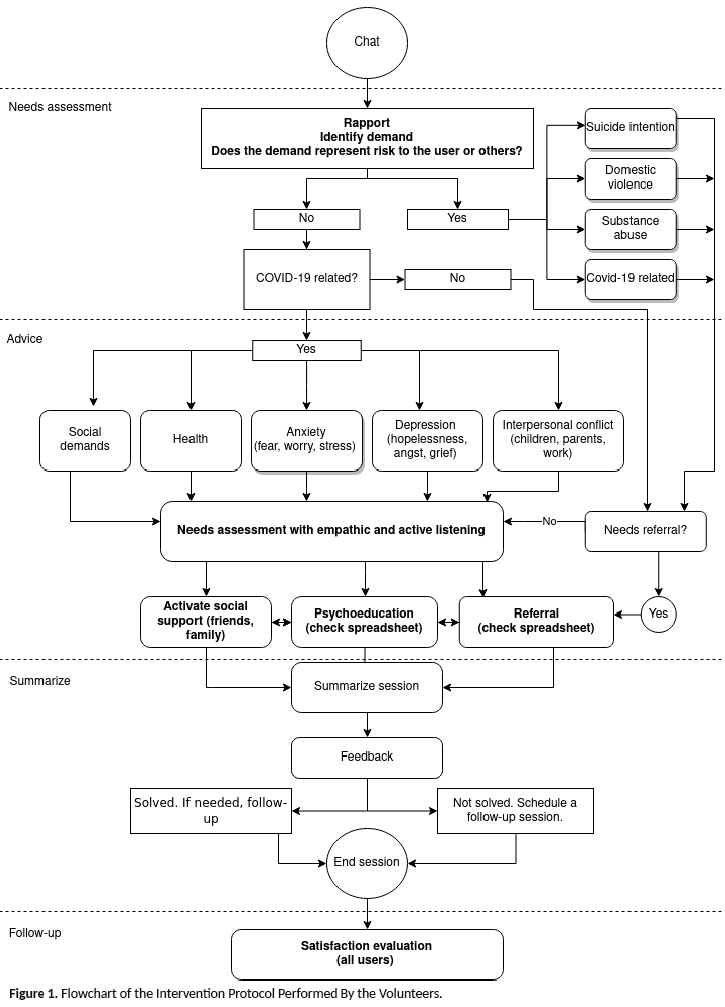

Afterward, we evaluated the protocol by running a pilot chat for about two weeks in Brazil and Argentina. We specifically assessed the user's demands protocol's feasibility (see figure 1) and referral to other services. Based on these results, we adjusted the intervention protocol.

Our chat intervention was designed to be goal-oriented and delivered in one session. The session had three steps: (1) needs assessment; (2) advice; and (3) referral. Trained volunteers accessed the user's needs, then established their primary demand using active listening techniques - which involves empathy, organization, feedback, and problem-solving. Based on the demand, volunteers suggested tools (e.g., breathing exercises, daily planning) and materials to help the person cope (e.g., psychoeducation material, health education, information on COVID-19) and, when needed, referred the user to free of charge services (e.g., psychotherapy, medical services, mental health, and social care). Volunteers were given shifts in order guarantee availability on the chat service from 8am to 8pm, from Monday to Friday. No prior scheduling was necessary by the users. Users also had the option to return to the platform as many times as they needed. Some users returned to the chat more than once when the volunteer marked that a specific follow-up was required.

Development of the Web Platform

After defining the protocol and intervention model, we made the platform available at the following URLs https://calmanessahora.com.br/ (for Brazilian users) and https://calmaenestemomento.com (for Argentinian users). The platform is a web application optimized for mobile devices and low-bandwidth connections. The chat system is delivered by tawk.to - a platform that offers chat conversations in real-time, questionnaires, a ticketsystem for monitoring cases, and support for multiple languages. The interactions between users and volunteers took place through encrypted connections using SSH certificates. The source code of the chat is available in the repository: https://github.com/henriquepgomide/calma-webapp

Selection of Support Materials and Services for Referral

We selected support materials in two fashions: (1) spontaneous, based on the team's knowledge indication of the group, and (2) systematic, based on searches on established sites of mental health institutions. Our selection prioritized textual, illustrative, audiovisual, or hypertext files with the following characteristics: (1) scientific grounded; (2) availability; (3) readability; (4) authority - higher education institutions, technical-scientific entities/associations, or specialized professionals.

We included in our database materials and referrals tailored to specific audiences (i.e., adults, children, elderly, women, health professionals) and themes (education, entertainment, family, health, mental health, social, technical/academic, work). We categorized these materials into (1) "support" materials for chat users and (2) "reference" materials aimed at training the team of volunteers or professionals who work directly with COVID-19. We chose referral services capable of responding to users' specific demands (e.g., psychological care, consultations via telemedicine, services for human rights violations, domestic violence, abusive relationships, problematic use of psychoactive substances, suicide ideation, mental disorders).

We created spreadsheets listing materials and referral services and shared them with the volunteers. These spreadsheets were readily available during chat sessions. We described the materials according to the author, year, subject, target audience, content covered, and URL in the spreadsheet. In the referral services spreadsheet, we described the services by name, type of service, urgency service (24h), modality of service (face-to-face/online), URL.

According to users' needs, we referred them to different services. Users who reported severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, other psychiatric disorders and/or health impairments were referred to online psychological interventions or the regular care network (e.g., Psychosocial Care Centers [CAPS] or psychiatric emergencies). Users under high-risk (i.e., suicide, self-mutilation, who were suffering from violence) were referred to protection services (e.g., suicide hotlines, local mental health public services [CAPS], general and psychiatric emergencies) or public safety services (e.g., human rights hotline, general emergency telephone line from the police, women, children and gender protection lines). Users who reported other social vulnerabilities were referred to public social services or the available healthcare network.

We added materials to the spreadsheets over time, based on to the demands that surfaced. Due to the difficulty of compiling all health services in Brazil and Argentina, we also searched for services in the user's home municipalities. Volunteers received training to use and update the spreadsheets.

Recruiting and Supervision of Volunteers

The intervention was conducted by 77 volunteer professionals and students of health and humanities programs, such as Psychology, Nursing, Pedagogy, Social Communication, Secretariat, Social Service, Medicine, and Physical Education. 47 volunteers were Brazilian, and 30 were Argentinean. We invited the volunteers to join the project based on previous work experiences.

We trained all volunteers to use the tawk.to features and perform the chat intervention. Due to the size of the group, we divided the volunteers into smaller teams responsible for (1) the intervention itself, (2) coration of the referral materials and services, (3) marketing, and (4) platform maintenance. Undergraduate students who did not feel able to work on the chat intervention took on administrative tasks. Volunteers did their first interventions in pairs. Each pair was composed by one volunteer with clinical experience and one without it.

The volunteers were supervised by ten psychologists from four Brazilian universities and ten supervisors from the National University of Tucumán (UNT), Argentina. Supervisors were responsible for (1) developing the intervention protocol and (2) volunteer training. All supervisors were psychologists and had clinical experience in brief interventions in health care. They performed weekly supervision meetings, provided continuous training and real-time supervision, when requested by the volunteer.

The weekly supervision teams were composed of small groups of students with varied experience; recent graduates and more experienced professionals were matched with less experienced volunteers. During the supervision meetings, all volunteers could access the chat transcripts after signing a confidentiality and privacy agreement. Often, supervisors suggested discussing complex cases in detail (i.e., suicide) for all volunteers collectively.

The volunteers selected educational materials and services to be indicated to users, choosing the most appropriate for each case. For this reason, during supervision, the content of these materials and the objectives of each service were discussed.

Given the complexity and diversity of some new cases, some referrals were made by e-mail at a later moment. Supervisors also added educational material and services to spreadsheets. We routinely asked users to give feedback on the relevance and access of the suggested referrals.

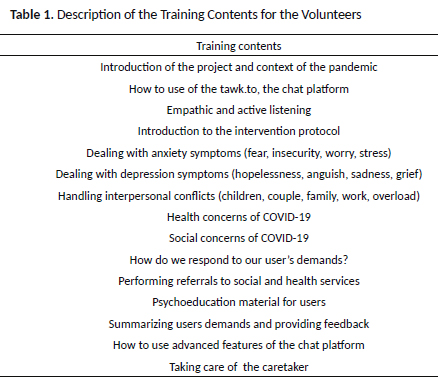

Volunteer Training

Volunteer training was held online, lasted 8 hours, and was divided into three days. Its content is shown in Table 1. Reading material was also provided.

First, volunteers were introduced to the tawk.toplatform and the intervention protocol, emphasizing the initial assessment and the decision tree (Figure 1). Then, they received training focused on empathetic intake and active listening for problems, such as social and health concerns related to COVID-19, management of anxiety symptoms (fear, insecurity, worry, and stress), management of depression and grief symptoms (hopelessness, anguish, sadness) and interpersonal conflicts (children, couple, family, work, overload, violence).

We used training materials produced by institutions such as APA (2020), International Red Cross (2020), Fiocruz (2020), Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2020),WHO (PAHO, 2015; WHO, 2020c), and Psychology Tools (n.d). Volunteers received guidance on ways to respond to user's demands backed by psychoeducation and health education materials targeted to their needs. The spreadsheets with educational material and referrals to services were also introduced. We instructed the volunteers to ask for feedback about the service. In the following stage, we presented the environment of the chat tool.

Finally, we presented the topic "Taking care of the caregiver." All training was recorded and made available for them to consult at any given time. In the end, all volunteers signed a term of responsibility and were asked for feedback on the training. General feedback emphasized the need for more time for discussion and more role-playing. As a strategy to fill these gaps, continuous training was offered in supervision groups, with a workload of two hours per week.

We covered additional topics in the second stage of training, based on users' demands and volunteers' main difficulties. Themes included: suicide ideation, domestic violence, management of anxiety crises, unemployment, bereavement, relaxation strategies, role-playingpractices, food compulsion, and child maltreatment. Also, we introduced new materials and referrals to social and health services.

Evaluation of Training. Volunteers were invited to answer a questionnaire about the training held in Brazil (BR) and Argentina (AR). Answers indicated general satisfaction with the training. On a scale where 1 would indicate very low satisfaction and 5 very high satisfaction, 96.6% of the answers (BR) and 94.7% (AR) ranged between 4 and 5. On the relevance of the training content, 90.3% of the responses were between 4 and 5 in Brazil and 94.5% in Argentina (1 would indicate that the content covered was irrelevant to the work of the volunteer, and 5 would indicate that the content covered was very relevant). There was no answer 1 and 2 in both questions for Brazilian volunteers and only one answer '2' in the first question for Argentineans. Finally, 83.9% (BR) and 89.5% (AR) considered the workload adequate, 9.7% (BR) and 10.5% (AR) considered it insufficient. 6.5% considered the training too long (BR).

Characterization of the Intervention Users

For a general characterization of users and their behaviors on the platform, we extracted data from Google Analytics and the Tawk.tochat platform between April 14 and May 26, 2020. Age and gender data were recovered from 46.6% of all users who accessed the intervention site. During the analysis period, the platform received 4,117 users, and the number of sessions and pages visited was 6,471 and 19,185, respectively. A total of 1,107 intervention sessions were delivered, with an average length of 15 minutes. Approximately 70% of the users were female. The frequency of users per age group was 26.6% between 18 and 24 years old; 34.5% between 25 and 34 years old; 14.6% between 45 and 54 years old; 9.6% between 55 and 64 years old and 0.6% above 65 years old. Most of the accesses were from Brazil (84.2%) and Argentina (12.6%). Users from other countries (United States, China, Japan, Portugal, Peru, among others) represent the rest of the accesses (3.2%). The three Brazilian states with the highest number of accesses were Minas Gerais (51.2%), São Paulo (13.0%), Rio de Janeiro (12.3%).

Discussion

In this study we presented the development and implementation of a chat intervention for adults dealing with general psychological distress in the COVID-19 pandemic. The main innovation of our intervention was the feasibility of creating a helpful bilingual chat tool that required quick implementation. In less than two months, more than a thousand chat sessions occurred. Our intervention allowed the evaluation and referral of its users to social and health services, in addition to the provision of psychoeducational materials.

Although chat interventions have access barriers (i.e., technology is not widespread in Brazil and Argentina), they can reach an underserved population due to mobility problems, distance, absence of face-to-face services, or financial unavailability. The model we designed allowed users to take further steps to solve their complaints in one session. In some cases, the intervention has served as a gateway to early care and preventive mental healthcare.

The on-call chat format, in which the user finds a volunteer available to chat, has presented itself as an essential low threshold support strategy. Often, people in psychological distress take time to share information about their emotional state and have difficulties accessing a support network. Having immediate access to a support chat tends to require a lesser degree of effort than searching for services and professionals, whether in terms of energy spent or in terms of confidentiality and privacy. In this sense, the chat is a valuable resource for user's engagement in the face of their suffering. This engagement is made possible by committing the user to strategies for managing personal and social resources.

In particular, the chat offers help privately through a protection tool. The chat format is particularly advantageous for users who share their household with other residents and need confidentiality to deal with their problems. For example, users can seek help when facing a threatening situation inside their house (e.g., family violence). Although the chat's initial purpose was not a gateway to urgent and high-risk cases, we received complaints associated with suicide ideation and domestic violence risk. Those demands required specific training regarding elements in users' discourse, indicating violence or suicide risk and making referrals to specialized services.

Another advantage of the platform is the possibility for volunteers to indicate materials with scientific rigor. At a time when there is an overload of health information (e.g., on the severity of COVID-19, the importance of social isolation, and the effectiveness of drugs to treat COVID-19), it is essential that health professionals are available on the internet to provide guidance based on scientific evidence and that they can refer users in need to mental health services.

One limitation of the assistance we provided is its unavailability on weekdays, from 8pm to 8am, and on weekday. To mitigate such problems, we reached out to people who entered our platform and could not begin a chat via e-mail and invited them to schedule a session. Another challenge was disseminating the service in different medias for greater regional and national reach in both countries. To advance in this aspect, we advertised it on social networks, radio, and TV newcasts. A third limitation was the lack of evidence on user satisfaction and cost-effectiveness, which are still to be investigated.

Final considerations

The elaboration and definition of the support service via chat required precise specifications of the format, goals, and limitations. It was possible to reach the planned stages of development and implementation of the chat platform.

The whole process took place in a systematized and iterative way. Also, the use of participative and consensus-based methodologies, involving researchers and volunteers, allowed an improved workflow. Another important aspect was the adequacy of cross-cultural implementation between the two countries, Brazil and Argentina, making it possible to contextualize the initiative for both distinct. Further studies should assess more systematically the effectiveness of this intervention model, and user's satisfaction with the service delivered.

We consider that this initiative has the potential of reaching a wider population due to (1) its feasibility of development and implementation; (2) its relevance not only for the current moment of the COVID-19 outbreak, (3) its potential to reduce barriers of access to care and (4) it is considered a good practice to be implemented for other health conditions.

References

Agyapong, V. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Health system and community response to a text message (Text4Hope) program supporting mental health in Alberta. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(5):e5-e6. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.114 [ Links ]

Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Rice, S., D'Alfonso, S., Leicester, S., Bendall, S., Pryor, I., ... Gilbertson, T. (2020). A Novel multimodal digital service (moderated online social therapy+) for help-seeking young people experiencing mental ill-health: pilot evaluation within a national youth e-mental health service. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e17155. doi: 10.2196/17155 [ Links ]

American Psychological Association. (2020). APA COVID-19 Information and Resources. Continually updated by APA for psychologists, healthcare workers, and the public. Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19# [ Links ]

Cucinotta, D., & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO Declares COVID-19 to Pandemic. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 157-160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 [ Links ]

Duan, L., & Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 300-302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0 [ Links ]

Fiocruz. (2020). Saúde mental e atenção psicossocial na pandemia COVID-19 – recomendações gerais. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Retrieved from https://www.fiocruzbrasilia.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Sa%C3%BAde-Mental-e-Aten%C3%A7%C3%A3o-Psicossocial-na-Pandemia-Covid-19-recomenda%C3%A7%C3%B5es-gerais.pdf [ Links ]

Gallegos, M., Zalaquett, C., Luna Sánchez, S. E., Mazo-Zea, R., Ortiz-Torres, B., Penagos-Corzo, ... Lopes Miranda, R. (2020). How to face the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in the Americas: Recommendations and lines of action on mental health. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 54(1), 1-28. doi:10.30849/ripijp.v54i1.1304 [ Links ]

Gomide, H. P., Martins , L. F., & Ronzani, T. M. (2013). Is it time to invest in computerized behavioral interventions in Brazil? Psicologia em Estudo, 18(2), 303-311. doi: 10.1590/S1413-73722013000200011 [ Links ]

Gould, C. E., & Hantke, N. C. (2020). Promoting technology and virtual visits to improve older adult mental health in the face of COVID-19. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(8), 889-890. doi: 10.1016%2Fj.jagp.2020.05.011 [ Links ]

Hoermann, S., McCabe, K. L., Milne, D. N., & Calvo, R. A. (2017). Application of synchronous text-based dialogue systems in mental health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research, 19(8), e267. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7023 [ Links ]

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2020). Guia Preliminar - como lidar com os aspectos psicossociais e de saúde mental referentes ao surto de covid-19. Retrieved from https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-03/IASC%20Interim%20Briefing%20Note%20on%20COVID-19%20Outbreak%20Readiness%20and%20Response%20Operations%20-%20MHPSS%20%28Portuguese%29.pdf [ Links ]

International Red Cross. (2020). First psychological care, remote, during the outbreak of COVID-19. Retrieved from https://pscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Remote-PFA.pdf [ Links ]

Miranda, C. F., & Miranda, M. L. (1996). Building the helping relationship (10th ed.). Belo Horizonte: Growing. [ Links ]

Muñoz, R. F. (2010). Using evidence-based internet interventions to reduce health disparities worldwide. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(5), e60. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1463 [ Links ]

Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses. (2020). Guia de orientação para linha de atendimento telefónico em fase pandémica covid-19. Retrieved from https://www.ordemdospsicologos.pt/ficheiros/documentos/doc_apoio_pratica_atendimento_telefonico.pdf [ Links ]

Pan American Health Organization. (n.d.). Proteção da saúde mental em situações de epidemias. Washington: Author. Retrieved from https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/Protecao-da-Saude-Mental-em-Situaciones-de-Epidemias-Portugues.pdf [ Links ]

Pan American Health Organization. (2015). Cuidados Psicológicos: guia para trabalhadores de campo (M. Gagliato, Trans.). Geneve: Author. Retrieved from https://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=prevencao-e-cont-doencas-e-desenv-sustentavel-071&alias=1517-primeiros-cuidados-psicologicos-um-guia-para-trabalhadores-campo-7&Itemid=965 [ Links ]

Pan American Health Organization. (2020). Manejo clínico de condições mentais, neurológicas e por uso de substâncias em emergências humanitárias. Guia de intervenção humanitária mhGAP (GIH-mhGAP). Brasilia: Author. Retrieved from https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51948 [ Links ]

Paterson, L., & Eisenberg, S. (2003). The counseling process (3rd ed.). São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Portaria n. 467. (2020, March 20). Dispõe, em caráter excepcional e temporário, sobre as ações de Telemedicina, com o objetivo de regulamentar e operacionalizar as medidas de enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional previstas no art. 3º da Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, decorrente da epidemia de COVID-19. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde. Retrieved from http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-467-de-20-de-marco-de-2020-249312996 [ Links ]

Psychology Tools. (n.d). Psychological resources for Coronavirus (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.psychologytools.com/psychological-resources-for-coronavirus-covid-19/ [ Links ]

Ravindran, S., Channaveerachari, N. K., Seshadri, S. P., Kasi, S., Manikappa, S. K., Cherian, A. V., ... George, S. (2020). Crossing barriers: Role of a tele-outreach program addressing psychosocial needs in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53, 102351. doi: 10.1016%2Fj.ajp.2020.102351 [ Links ]

Resolução n. 466.(2012, December 12). Trata de pesquisas e testes em seres humanos. Brasília, DF: Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Retrieved from http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf [ Links ]

Resolução n. 4. (2020, March 26).Dispõe sobre regulamentação de serviços psicológicos prestados por meio de Tecnologia da Informação e da Comunicação durante a pandemia do COVID-19. Brasília, DF: Conselho Federal de Psicologia. Retrieved from http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-n-4-de-26-de-marco-de-2020-250189333 [ Links ]

Scholten, H., Quezada-Scholzb, V., Salasc, G., Barria-Asenjod, N. A., Rojas-Jarac, C., Molina, R., ... Somarriva, F. (2020). Psychological approach of the covid-19: A narrative review of the latin american experience. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 54(1), e1287. [ Links ]

Sheth, S., Ganesh, A., Nagendra, S., Kumar, K., Tejdeepika, R., Likhitha, C., Murthy, P., & Chand, P. (2020). Development of a mobile responsive online learning module on psychosocial and mental health issues related to COVID 19. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102248. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102248 [ Links ]

Soklaridis, S., Lin, E., Lalani, Y., Rodak, T., & Sockalingam, S. (2020). Mental health interventions and supports during COVID-19 and other medical pandemics: A rapid systematic review of the evidence. General Hospital Psychiatry, 66, 133-146. doi: 10.1016%2Fj.genhosppsych.2020.08.007 [ Links ]

United Nations. (2020, March 18). Covid-19: OMS divulga guia com cuidados para saúde mental durante pandemia. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/pt/story/2020/03/1707792 [ Links ]

Webb, T. L., Joseph, J., Yardley, L., & Michie, S. (2010). Using the internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020a). Responding to community spread of COVID-19. Geneve: WHO. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/responding-to-community-spread-of-covid-19 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020b). National Capacities Review Tool for a novel coronavirus (nCoV). Geneve: Author. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/national-capacities-review-tool-for-a-novelcoronavirus [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020c). Mental Health Considerations during COVID-19 Outbreak. Retrieved from https://pscentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WHO-mental-health-considerations.pdf [ Links ]

Xavier, L. N., Oliveira, G. L., Gomes, A. A., Machado, M. F. A. S., & Eloia, S. M. C. (2014). Analisando as metodologias ativas na formação dos profissionais de saúde: uma revisão integrativa. Sanare, 13(1), 76-83. Retrieved from https://sanare.emnuvens.com.br/sanare/article/view/436 [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Avenida Purdue, s/nº, Campus Universitário / Departamento de Educação

CEP 36.570-900, Viçosa/MG.

Telefone: (31) 3612-7500 / (31) 92000-2538.

Email: henriquepgomide@gmail.com

Received in 31.may.20

Revised in 17.nov.20

Accepted in 07.jan.21

Henrique Pinto Gomide, Doutor em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF), é Professor Adjunto da Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV).

Carolina Silva Bandeira de Melo, Doutora em Educação e em História das Ciências pela Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) e pela École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), é Professora Adjunto da Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV). Email: carolina.bmelo@ufv.br

Elisa Maria Barbosa de Amorim-Ribeiro, Doutora em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), é Professora Titular da Universidade Salgado de Oliveira (UNIVERSO)- Niterói/ RJ. Email: ribeiro.emba@gmail.com

Joanna Gonçalves de Andrade Tostes, Doutora em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF), Pesquisadora do Centro de Referência em Pesquisa, Intervenção e Avaliação em Álcool e outras Drogas (CREPEIA). Email: joanna@tostes.org

Lílian Perdigão Caixêta Reis, Doutora em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Pós-Doutora em Psicologia pelo Programa Nacional de Pós-Doutorado Institucional pela Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), é Professora Associada I no Departamento de Educação da Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV). Email: lilian.perdigao@ufv.br

Maria Lorena Lefebvre, Licenciada em Psicologia pela Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT), Chefa de Trabalhos Práticos de Teorias e Intervenções no campo grupal e das comunidade e Práticas Profissionais Supervisionadas no campo de Intervenção Social Comunitária da Facultad de Psicologia da Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT). Email: lorelefebvre81@gmail.com

Rodrigo Lopes, Doutor em Psicologia Clínica pela Universidade do Minho (UMinho), Portugal, é Pesquisador sênior do Instituto de Psicologia, Departamento de Psicologia Clínica e Psicoterapia da Universidade de Berna (UniBe), Suíça. Email: rodrigo.lopes@psy.unibe.ch

Tiago Paz e Albuquerque, Doutor em Psicologia Social pela Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), é Professor Adjunto I da Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV). Email: tiagopaz@ufv.br

Yone Gonçalves de Moura, Mestra em Psicobiologia pela Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), é Psicóloga clínica autônoma. Email: ygmoura@gmail.com

Telmo Mota Ronzani, Doutor em Ciências da Saúde pela Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP); Pós-Doutor em Saúde Mental pela Universidade de São Paulo (USP); Estágio Pós-Doutoral em Saúde Pública pela University of Connecticut Health Center (Uconn Health Center), é Professor Associado do Departamento de Psicologia da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF) e Bolsista de Produtividade CNPq 1D. Email: tm.ronzani@gmail.com