Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

versión impresa ISSN 1413-294Xversión On-line ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.26 no.2 Natal abr./jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20210020

10.22491/1678-4669.20210020

SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AND MENTAL HEALTH

Fake news in the Covid-19 pandemic: Conspiracy theories, alternative truths, and benevolent advice

Boatos em forma de fake news na pandemia da Covid-19: teorias da conspiração, verdades alternativas e conselhos bondosos

Rumores en forma de fake news en la pandemia de Covid-19: teorías de conspiración, verdades alternativas y buenos consejos

Rafael Moura Coelho Pecly WolterI; Flaviane da Costa OliveiraI; Álvaro Rafael Santana PeixotoI; Thiago Rafael SantinI; Antonio Marcos Tosoli GomesII; Julia Ott DutraIII; Ana Clara Lopes Oliveira ReisI; Heloisa Maria Silva e Silva PintoI

IUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo

IIUniversidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

IIIInstituto Capixaba de Ensino, Pesquisa e Inovação em Saúde

ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic has created an informational tide in which rumors in the form of fake news disseminated by individual and official agency communications saturated people with sometimes contradictory messages. Grounded on the perspective of the social psychology of rumors, this study aimed to analyze the unique and differential characteristics of news proven to be fake news in order to obtain criteria for recognizing this phenomenon. We selected posts about Covid-19 shared on social networks by individuals (n = 100) and by official agencies (n = 100) verified as fake news on specialized sites (n = 100). A descending hierarchical classification was performed and fake news presented three singularities: emphasis on conspiracy theories, presentation of alternative truths to those of governments, and promotion of benevolent advice for the protection and cure of the disease. Such results allow the insertion of these characteristics into fake news search algorithms and the adaptation of the communication of official bodies, for the prevention of misinforming news.

Keywords: covid-19; fake news; rumors; social representations; social psychology.

RESUMO

A pandemia da Covid-19 criou uma maré informacional na qual boatos em forma de fake news, comunicações individuais e de órgãos oficiais saturam as pessoas com mensagens por vezes contraditórias. A partir da psicologia social dos boatos, objetiva-se estudar as características singulares e diferenciais de notícias comprovadas como fake news, para obter critérios para reconhecer esse fenômeno. Foram selecionadas mensagens sobre Covid-19 compartilhadas em redes sociais por indivíduos (n = 100), por órgãos oficiais (n = 100) e averiguadas como fake news em sítios especializados (n = 100). Uma classificação hierárquica descendente foi realizada e as fake news apresentaram três singularidades: ênfase em teorias da conspiração, apresentação de verdades alternativas às dos governos e promoção de conselhos bondosos para proteger-se e curar-se da doença. Tais resultados permitem a inserção dessas características em algoritmos de busca de fake news e a adaptação da comunicação de órgãos oficiais, para prevenção de notícias que desinformam.

Palavras-chave: covid-19; fake news; boatos; Representações Sociais; Psicologia Social.

RESUMEN

La pandemia de Covid-19 creó una marea informativa en la que los rumores en forma de fake news, comunicaciones individuales y de organismos oficiales bombardean a las personas con mensajes a veces contradictorios. Basado en la psicología social de los rumores, el objetivo es estudiar las características singulares y diferenciales de las noticias comprobadas como fake news, con el fin de obtener criterios que permitan reconocer este fenómeno. Se seleccionaron mensajes sobre Covid-19 compartidos en las redes sociales por individuos (n = 100), por organismos oficiales (n = 100) y verificados como fake news en sitios especializados (n = 100). Se realizó una clasificación jerárquica descendente y las fake news mostraron tres singularidades: énfasis en teorías de conspiración, presentación de verdades alternativas a las de los gobiernos y difusión de consejos benéficos para protegerse y curarse de la enfermedad. Dichos resultados permiten la inserción de estas características en algoritmos de búsqueda de fake news y la adaptación de la comunicación de organismos oficiales, para evitar noticias que desinforman.

Palabras clave: covid-19; fake news; rumores; Representaciones Sociales; Psicología Social.

The recent circulation of the new coronavirus and the consequent respiratory syndrome pandemic have gained increasing space in the public sphere. Scientific research from different fields has sought to understand its clinical, subjective, social, and economic implications (Bezerra, Silva, Soares, & Silva, 2020; Villela, 2020). This international health emergency, as considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Bezerra et al., 2020), required intersectoral governmental decisions in different spheres and the need for changes in behaviors and habits in the micro space of the daily life of many Brazilians.

SARS-CoV-2 (also called HCoV-19) is a virus of the coronavirus family, the seventh of such type known to be able to infect humans and the cause of Covid-19 - short for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Andersen, Rambaut, Lipkin, Holmes, & Garry, 2020). Human contagion by the virus was first reported on December 31, 2019, in the city of Wuhan, Hubei province, China. On January 30, 2020, the disease was declared a public health emergency of global concern and characterized as a global pandemic by the WHO on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020a, WHO, 2020b).

The high transmissibility of the virus becomes explicit in the number of confirmed cases in the world: in the third week of October 2021, there were 240,631,670 confirmed cases (WHO, 2021), data that may be higher due to lack of testing (Li et al., 2020) and the fact that part of the patients is asymptomatic (Black, Bailey, Przewrocka, Dijkstra, & Swanton, 2020). The lethality of the disease globally is also noteworthy, with a total of 4,903,911 deaths in the third week of October 2021 (WHO, 2021).

In Brazil, by the third week of October, there were 21,644,464 cases and 603,282 deaths (Ministério da Saúde, 2021), numbers that are probably lower than reality, also due to the underreporting of cases in the country (Alonso et al., 2020).

Besides being a major global public health problem, coronavirus also heavily impacts social and economic life (Nicola, 2020) in affected countries since one of the main measures to contain the disease is partial or total social isolation (Hellewell, 2020).

The coronavirus containment measures in Brazil have caused great debate in the social and political fields (Rodrigues & Azevedo, 2020), with groups that are either favorable or against the isolation measures, due to the most diverse arguments. This division of opinions caused fertile ground for the spread of diverse and often contradictory information (Recuero & Soares, 2020) concerning the guidelines issued by official national and international bodies. It is in this context that the concept of fake news becomes relevant in the relationship of groups with the Covid-19.

This research falls within the scope of the social psychology of communication (Abric, 1996; Moscovici, 1961/2012; Rouquette, 1998), and focuses on how the new coronavirus was broadcasted in virtual social networks by people and government agencies, and news verified as false (fake news). We believe that the understanding and characterization of the messages circulating in the virtual environment become essential for planning communication strategies aimed at the prevention and mitigation of the virus circulation.

Fake news and the Covid-19 Pandemic

One of the distinguishing features of the Covid-19 pandemic is the distressing informational situation that accompanies it. Its level of misinformation or disinformation is so great that the director of the World Health Organization called it an "infodemic," a neologism, calling on governments, institutions, professionals, and citizens to combat it as well (Zarocostas, 2020). One part of this "infodemic" is the phenomenon called fake news.

This term became known when it was widely used in the 2016 presidential election dispute in the United States (Mukerji, 2018). Since then, its use has grown significantly in the public sphere, producing academic research and also public and private policies in the digital sphere to deal with its impacts, such as the development of automatic detection tools (Pérez-Rosas, Kleinberg, Lefevre, & Mihalcea, 2017) and its use in virtual social networks. But, after all, what is fake news?

Epistemology, in general, analyzes knowledge in a veritistic way, that is, truth-oriented, by the content of news or messages. However, social epistemology brings into discussion the political character of knowledge and its use, producing mixed definitions, more or less rigorous or flexible in the criteria in each domain.

According to Gelfert (2018), fake news can be defined as a type of misinformation, with three characteristics: it is presented in a news format, usually leads to falsehoods, and is designed to be deliberately deceptive. For Jaster and Lanius (2018), fake news is news in which there is (a) a lack of truth and (b) a lack of veracity, that is, it is false or misleading and also propagated with the intention to deceive. In this sense, we will associate the concept of rumors, from social psychology, with that of fake news, which has the virtual environment as its material support.

Beyond the theoretical-conceptual debate, there are applied researches on the fake news phenomenon that help the understanding of its contents. Schulz, Wirth, and Müller (2020) analyzed populist attitudes within the social identity approach in the European party political context, verifying how populist citizens attribute fake news to other social groups, depersonalizing its members. Thus, the empirical analysis of fake news can help us understand the "infodemic" and, consequently, the pandemic itself.

From a practical point of view, in the pandemic scenario, there are reports of the effects of fake news on inter-group relations, besides individual problems of adherence to prevention measures, due to misinformation or hostile perceptions of the information issued by official sources.

Regarding inter-group relations, in Japan there were reports of racism against the people of China due to information coming from fake news claiming that contaminated Chinese coming from Wuhan were bypassing health blockades, generating reactions of loathing and hatred (Shimizu, 2020).

Fake news in the Brazilian context is already the object of preliminary research in the health area. Neto et al. (2020) analyzed 70 items from the Ministry of Health's fake news database, dividing them into five categories: health authorities' speeches (40), therapeutic (17), prevention (9), prognostic (2), and vaccines (2). They point out individual losses, for those who follow the false recommendations, and collective, for the credibility of official and scientific institutions, reinforcing that health education is the way to overcome the problem.

Covid-19, a fertile ground for rumors

Faced with scenarios of risk exposure and emotional stress, individuals resort to simplified explanations of reality such as rumors (Allport & Postman, 1945), to the detriment of scientific and official communication (exaggerations, omissions, etc.), but these are not constructed by chance, since they reveal aspects of group belonging. Rumors can spread distorted or untrue information (fake news, in the virtual environment), amplifying the concern of health authorities and justifying their investigation, due to the wide reach and the risk of exposing the population to risky prescriptions.

The pandemic that society is currently experiencing has psychosocial characteristics similar to the World War II since "(...) within a group the spread of rumors about a particular subject is in direct relation to the importance and ambiguous nature of the subject in the life of each member of the group" (Allport & Postman, 1947, p. 33). The pandemic is directly related to everyone's life, and simultaneously there is a tide of sometimes contradictory information circulating. Such a situation, where there is fear of getting sick, for oneself and for those around, as well as the economic crisis, generates high levels of anxiety.

Anxiety is related to the implication that people adopt in front of the object of crisis and threat. For Rouquette (1988, 1997), three characteristics that form personal implication occur in situations of great rumor dissemination: (1)the object touches people individually (I am personally affected by the subject); (2)the object is valued (it is seen as important); (3)there is a need for control (the belief that one can influence the object).

Studies have shown that in crises situations the levels of personal involvement are increased and lead to more emotional and less cognitive ways of thinking (Gruev-Vintila & Rouquette, 2007). Given the magnitude of the current crisis (WHO, 2020a), levels of personal implication are likely to be high, which, coupled with the impossibility to verify and the ambiguity of much information, creates fertile ground for the spread of rumors.

More specifically, fake news circulating on social media can be expected to have characteristics of rumors (Rouquette, 1975, 1991), which are: (a) non-verifiability of the content during communication (source is usually attributed to someone competent, such as a scientific authority or a person in the social circle, neighbor, or friend of a friend); (b) content negativity; (c) implication of the individuals among whom the rumors circulate; (d) transformation of the content during communication.

Rumors and Their Social Logic of Thought

According to Rouquette (1973), social thinking is "social" in two aspects. First, because it focuses on the everyday situations of social groups, whose objects are issues of interest and relevance in people's lives. Secondly, because the social insertion (social norms, position) of people is a crucial component of this form of thinking. In summary, social thinking is about how people's knowledge and knowledge elaboration deals with objects of relevance in their lives and stems from their respective social insertions.

According to Rouquette (1998), rumors circulate in a tripod format, by bringing group-acceptable knowledge (knowledge) transmitted (communication) into a network of social proximity (sociability). In his various researches, Rouquette (1994, 1998) demonstrates that social representations serve as a framework for the adaption of rumors. In other terms, the way the group conceives different objects will be a guide to what content is acceptable and able to be passed on to other people in the group. This is demonstrated in empirical studies by Rouquette (1994, 1998), in which content that does not conform to the group's thinking is not passed on, but is omitted or transformed. Naturally, the transformation brings the content closer to what is thought by the group about the object (social representation).

Social representations have three dimensions (Rouquette & Rateau, 1998): functional (or practical), descriptive, and normative (or evaluative). The practical dimension (Abric, 1994; Guimelli, 2003) corresponds to the "instrumental relationship that individuals maintain with the object of representation. Indeed, this dimension can be considered directly related to the social practices that subjects develop in relation to the object" (Guimelli, 2003, p. 136). This dimension is closely linked to the concrete practices and actions exercised. The evaluative dimension, according to Guimelli (2003, p. 136), is "linked to values, norms or stereotypes strongly salient in the group; it allows the group to make judgments about the object. This dimension is probably marked by ideological and historical factors." Finally, the descriptive dimension concerns the activation of elements that define the object, such as events, characteristics, and facts related to it. (Wolter, Wachelke, & Naiff, 2016, p. 1146).

As described above, in Social Psychology studies, the current pandemic is a fertile ground for rumor circulation. The environment is ambiguous, with a high amount of unverifiable news, about a topic of high personal involvement (closeness, valuation, and control). It is also to be expected that rumors possess the three knowledge characteristics of social representations: prescription (functional dimension), description, and judgment.

The research objectives consist of: learning about the lexical classes present in virtual social media communications from individuals (popular communications), from governments and official bodies, and news attested as false; establishing specific characteristics for the news attested as fake.

Method

Since this is an investigation of data obtained publicly through Internet access, this research followed Resolution No. 510/2016 (Resolução n. 510/2016) of the Brazilian National Health Council, dispensing with the approval of the Research Ethics Committee and guaranteeing anonymity to the senders of the analyzed messages.

Data Collection

The data source for this investigation were 300 posts related to the new coronavirus and Covid-19, publicly available in the virtual environment. The corpus was composed by convenience during the month of April 2020, including all publications accessed until 300 items were reached, without repetition of publications.

The sources comprise three groups taken from virtual social networks: (i)100 posts from individual profiles; (ii)100 posts from profiles of official agencies (at the municipal, state, federal and World Health Organization levels); (iii)100 news items that have been verified as false by electronic verification sites and circulated as individuals' posts.

In group 1 (popular communication), the content posted by Internet users reveals information of interest spontaneously shared with their peers, and may reflect true or false information, whether official, personal opinion, or rumors without proof or undetermined source. It is, therefore, a source of public and open access to popular communication and to the elements that make up the social representations around the analyzed phenomenon. The profiles accessed were chosen by convenience, mostly from the same region as the researchers, who used their social networks for the collection of fixed publications in the profile (feed or timeline), including temporary Instagram posts (stories).

In group 2 (official communication), the official communications reveal intentionally disseminated aspects, as a form of information and prescription of practices against the risks of the pandemic. The publications were collected in institutional profiles of the city halls of the metropolitan region of Vitória, E.S. (Vitória, Cariacica, Guarapari, Serra, Viana and Vila Velha), of the State Government of Espírito Santo, of the Ministry of Health of Brazil, of the Federal Government of Brazil, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Group 3 (fake news) presents publications certified as fake news by fact-checking agencies, but that were circulating in individual profiles on social networks. Therefore, the analyzed material was the original posts that circulated among Internet users, but collected from the sites of the verification agencies, being, therefore, necessarily attested as false, as opposed to publications of group 1.

Each of these data sets was presented individually and compared during the analysis. In all groups of posts we sought to collect proportionally on three social networks: Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter1. Only in group 3 this distribution did not occur, with 14 (fourteen) cases where the social network could not be determined.

Data Analysis

This paper refers only to the results of the analysis of textual elements. The lexical analysis was performed with the help of IRaMuTeQ, created in 2009 by the French researcher Pierre Ratinaud. Among the statistical possibilities, we chose the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC), a procedure developed by Max Reinert (1990). Each text corpus, referring to the three groups of posts mentioned above, was submitted separately to the procedure.

The class hierarchy is expressed by a dendrogram, or tree diagram, which is based on the principle of the greatest homogeneity within each class of words and the greatest possible differentiation between classes. Along with the main words that characterize the text (highest frequency and co-occurrence), the main text segments related to the classes are also presented. Despite simplifying the analysis, the researcher needs to read the results, name the classes, and interpret the relations pointed out by the statistical procedures, through previous knowledge about the empirical and theoretical field about the object (Oliveira, Gomes, & Marques, 2005).

Results

All dendrograms contained descriptive and prescriptive classes, however, popular communications and fake news also contained an evaluative class. In turn, the lexical class of conspiracy theories occurs only in the DHC of fake news.

Group 1 consists of popular communications and contains four classes. The corpus was composed of 100 texts, with 161 text segments, of which 111 (68.94%) were used, totaling 4,912 occurrences.

Class 2 (19/111, 17.1%), "what we should do", has as main words "avoid, use, wash, hand", bringing the specific aspect of the popular prescription regarding the pandemic, to actions that can be done here and now. Keeping social isolation, having good hygiene practices, avoiding contact, and being careful at work are ideas related to the popular messages.

Class 3 (35/111, 31.5%), "the pandemic here in Brazil", has "Brazil, death, confirm, country" as the words with greater distribution. It centralizes the descriptive dimension of the popular communications posts, containing ideas and information about the pandemic in Brazil, contamination, number of cases, exams, the virus, and related public policies, such as emergency income and the situation of families.

Classes 2 and 3 are linked by the character of proximity, both for the specific practices that need to be taken in everyday life and for the situation of the pandemic in the local and national context.

Class 4 (22/111, 19.8%), "technical-scientific aspects of the pandemic", is also descriptive, presenting the contents of the reified universe, using the official speeches, which are popularly reproduced, and associating with classes 2 and 3, by adding this type of ideas and information to the national context.

Class 1 (35/111, 31.5%), "stay at home, because it kills", connects to the others and constitutes the evaluative dimension of the group, with the words "home, stay, people, die" having the largest distribution. It presents the ideas concerning adherence to the general prescription "stay at home", motivated by the fear of death that the pandemic brings, constituting a negative judgment. Other terms that constitute the class concern the effects of the prescription, such as not being infected and lowering the curve, and the reasons for being afraid, such as the collapse of the health system, which occurred in Italy.

Group 2 consists of the official announcements from the federal government, the government of the state of Espírito Santo, and municipal governments of the metropolitan region of Vitória (Vitória, Cariacica, Guarapari, Serra, Viana, and Vila Velha), as well as from the WHO and contains four classes. The corpus was composed of 100 texts, with 310 text segments, of which 217 (70.00%) were used, totaling 9.941 occurrences.

Class 3 (34/217, 15.7%), "government justifications", has as main words "https link, message, hygiene, and measure", and constitutes the evaluative dimension of the official announcements. It recurrently brings links to official sites and pages outside the posts on social networks, indicating grounds for the content of the messages, generally of an admonitory nature concerning hygiene, isolation, and individual and collective care. Its function is to justify the public policies adopted and warn the population about the pandemic.

Class 1 (51/217, 23.5%), "the virus and the disease", constitutes the descriptive dimension, with words such as "Covid-19, use, circulation." These messages bring the identification of the official sources, also through reference to their websites outside the social networks, and contain information about the virus, the disease, the risk groups, the protocols adopted, the means and channels to seek more information about the health system, research and treatments available, and answer questions.

Classes 1 and 3 together form the governments' position and conception about the Covid-19 pandemic. They relate to class 4 (60/217, 27.6%), "tips for isolation at home", which is part of the prescriptive dimension, containing as words with the highest distribution "information, good, help, mental, physical". It is more general and suggestive, providing advice and information on health, with a biomedical technical-scientific nature, but also including social aspects. Physical and mental health care, such as exercise and habits to develop at home, are very frequent, as well as care and help for the elderly, neighbors, and people who are in risk groups or have greater difficulties.

Classes 1, 3, and 4 together were named "Covid-19 and daily life". Class 4 presents suggestive official communication. Class 2, on the other hand, opposed to all the others, presents compulsory prescriptions.

Class 2 (72/217, 33.2%), "what we should do", is the specific part of the prescriptive dimension, determining concrete individual actions, as can be seen in the words "wash, hand, water, soap." Most of the ideas and information in the messages of group 2 are contained in this class, which circumscribes the others, indicating the regulatory character of the official communications about individual conducts.

Group 3 consists of fake news checked by specialized electronic sites and also contains four classes. The corpus was composed of 100 texts, with 250 text segments, of which 178 (71.20%) were used, totaling 8,130 occurrences.

Class 1 (36/178, 20.2%), "quarantine for politicians and media," strongly shows the evaluative dimension of the group. It has as most frequent words "mayor, close, speak, governor", showing politicians and traditional media communicators as a preferential target of fake news. Many of the posts are of positions contrary or in favor of the quarantine, pointing to a supposed social category privileged for determining, disseminating, and encouraging, but not complying with the quarantine itself. There are also ideas about the closure of commerce, the situation of businesses, and the relations of the media with politicians.

Class 2 (50/178, 28.1%), "cases in Brazil and in the world", brings the descriptive dimension of the group, presenting false or distorted information about "coronavirus, death, case, number, cure." The deceitful character of fake news is easily seen in messages about the situation of cities and the country, comparisons with other countries, and disputed narratives about the statistical data and the characteristics of the disease.

Classes 1 and 2 are linked by the themes of social detachment and the magnitude of the pandemic. They connect to class 3, where fake news are interrelated and take the form of conspiracy theories.

Class 3 (42/178, 23.6%), "conspiracy theories," brings the descriptive and evaluative dimensions, as it disputes with governments, traditional media, and official agencies for explanations about the pandemic, usually through the use of group identity and ideological alignment, us versus them. The most frequent words, "China, Chinese, country, use", show that they attribute national origin, linked to a political-ideological regime, in a strategy that allows the delimitation of allies and adversaries in the "war on the truth of the pandemic." Conspiratorial messages sometimes involve unverifiable elements and warn of great risk, not of the pandemic, but of political-ideological domination, for which the pandemic was created or is being used.

Class 4 (50/178, 28.1%), "untruthful advice", circumscribes the others as it takes descriptions and evaluations as its basis and brings prescriptions. It has as main words "water, drink, take, throat", and consists mainly of messages about protections and alternative cures, either from unrecognized medical sources or from popular and traditional knowledge that are within anyone's reach. They vary in their relationships, pointing to a desire for healing, and minimization of the virus or the disease. Prescriptions are very specific and simple and can be conducted easily, such as, for example, drinking plenty of water and teas.

Discussion

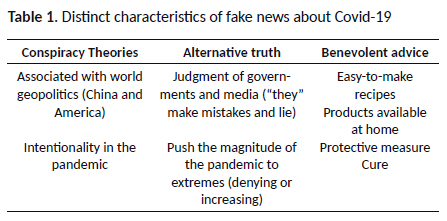

Fake news presented two singularities compared to the other two groups: singularity of lexical class and singularity of content. As for the first, it is important to note that only in fake news the conspiracy theories (Douglas, Sutton, & Cichocka, 2017) form a separate class, more specifically, messages convey issues of international politics (China and America) associated with intentionality, with terms like "plan" or "use". Rumors, since the works of Allport and Postman (1945), have this characteristic of attributing the origin of crises to governments, groups seen as powerful, or foreign countries with dark objectives. In this point we can notice that fake news are, in many cases, new clothes for the old rumor processes studied by social psychology since the last century.

The singular content of fake news carries another truth. Its evaluative dimension (Abric, 1994; Rateau & Lo Monaco, 2016; Rouquette & Rateau, 1998) is directed towards hostile perceptions of politics and governments, in contrast to the evaluative dimension of group 1, which is directed towards the social norm of detachment. The messages bring about measures of governments, conveyed by the media, which are seen as erroneous and untrue. There is also a shift in the perception of the magnitude of the pandemic, either denying its existence or attributing it to a cataclysmic dimension. Content pushed to extremes is another characteristic of the rumors described by Allport and Postman (1945), as well as by Rouquette (1998). Finally, "benevolent advice" shows easy recipes with products available at home, with protective and healing abilities.

The DHC class and the unique contents that only appear in fake news have three general characteristics that distinguish them from popular communications in general and messages originating from governments: conspiracy theories, the presentation of an alternative truth, and a set of benevolent pieces of advice. All three categories have a cognitive consistency (Rouquette, 1990) with what is thought by the group. In other terms, what is presented falls within the field of possibilities of occurrence of facts within the set of social representations shared by the groups that adhere to rumors in the form of fake news.

Therefore, the rumors about Covid-19 present in fake news are organized ranging from the general (with global conspiracy theories) to the individual (with everyday protective and healing actions).

Conceptually, these results lead us to believe that news attested as false is often presented in the format of rumors. This does not mean that this is always the case. Fake news can simply be fake news, for example, for a public person to promote himself or criticize an opponent. Such cases do not fall under rumor, as they are not in the spontaneous format of transmitting unverifiable information.

Finally, the three characteristics above can be included in different fake news search algorithms or inserted into announcements to the public about the characteristics of messages to be observed and have their sources verified.

References

Abric, J.-C. (1994). Représentations sociales: aspects théoriques. In J.-C. Abric (Ed.), Pratiques sociales et représentations (pp. 11-36). Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Abric, J.-C. (1996). Psychologie de la communication: Méthodes et théories. Paris: Colin. [ Links ]

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. J. (1945). Section of psychology: The basic psychology of rumor. Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, 8(2 Series II), 61-81. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1945.tb00216.x [ Links ]

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. J. (1947). The psychology of rumor. New York: Henry Holt. [ Links ]

Alonso, W. J., Schuck-Paim, C., Freitas, A. R. R., Kupek, E., Wuerzius, C. R., Negro-Calduch, .... Pinheiro, S. F. (2020). Covid-19 em contexto: comparação com a mortalidade mensal por causas respiratórias nos estados brasileiros. International Journal of Medicine and Health, 3, 1-21. doi: 10.31005/iajmh.v3i0.93 [ Links ]

Andersen, K. G., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W. I., Holmes, E. C., & Garry, R. F. (2020). The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine, 26(4), 450-452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9 [ Links ]

Bezerra, A., Silva, C. E. M., Soares, F. R. G., & Silva, J. A. M. (2020). Fatores associados ao comportamento da população durante o isolamento social na pandemia de COVID-19. Ciência Saúde Coletiva (Internet). Recuperado de http://www.cienciaesaudecoletiva.com.br/artigos/fatores-associados-ao-comportamento-da-populacao-durante-o-isolamento-social-na-pandemia-de-covid19/17551 [ Links ]

Black, J. R., Bailey, C., Przewrocka, J., Dijkstra, K. K., & Swanton, C. (2020). COVID-19: the case for health-care worker screening to prevent hospital transmission. The Lancet, 395(10234), 1418-1420. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30917-x [ Links ]

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 538-542. doi: 10.1177/0963721417718261 [ Links ]

Gelfert, A. (2018). Fake news: A definition. Informal Logic, 38(1), 84-117. doi: 10.22329/il.v38i1.5068 [ Links ]

Gruev-Vintila, A., & Rouquette, M.-L. (2007). Social thinking about collective risk: How do risk-related practice and personal involvement impact its social representations? Journal of Risk Research, 10(3-4), 555-581. doi: 10.1080/13669870701338064 [ Links ]

Guimelli, C. (2003). Le modèle des schèmes cognitifs de base: Méthodes et applications. In J.-C. Abric (Ed.), Méthodes d'étude des représentations sociales (pp. 119-143). Ramonville Saint-Agne, France: Érès. [ Links ]

Hellewell, J., Abbott, S., Gimma, A., Bosse, N. I., Jarvis, C. I., Russell, T. W., ... Funk, S. (2020). Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health, 8(4), 488-496. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30074-7 [ Links ]

Jaster, R., & Lanius, D. (2018). What is fake news? Versus: Quaderni di Studi Semiotici, 2(127), 207-227. doi: 10.14649/91352 [ Links ]

Li, R., Pei, S., Chen, B., Song, Y., Zhang, T., Yang, & W., Shaman, J. (2020). Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), Science, 368(6490), 489-493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221 [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde. (2021, June 21). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde (SVS/MS). Painel Coronavírus. Retrieved from https://covid.saude.gov.br [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2012). A psicanálise, sua imagem e seu público. (S. Fuhrmann, Trans.). Petrópolis: Vozes. (Original work published in 1961) [ Links ]

Mukerji, N. (2018) What is fake news? Ergo, 5(35), 923-946. doi: 10.3998/ergo.12405314.0005.035 [ Links ]

Neto, M., Gomes, T., Porto, F., Rafael, R., Fonseca, M., & Nascimento, J. (2020). Fake news no cenário da pandemia de Covid-19. Cogitare Enfermagem, 25: e72627. doi: 10.5380/ce.v25i0.72627 [ Links ]

Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., ... Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 Pandemic: A review. International Journal of Surgery, 1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 [ Links ]

Oliveira, D. C., Gomes, A. M. T., & Marques, S. C. (2005). Análise estatística de dados textuais na pesquisa das representações sociais: alguns princípios e uma aplicação ao campo da saúde. In M. S. S. Menin & A. M. Shimizu (Eds.), Experiência e representação social: questões teóricas e metodológicas (pp. 157-199). São Paulo: Casa do psicólogo. [ Links ]

Pérez-Rosas, V., Kleinberg, B., Lefevre, A., & Mihalcea, R. (2017). Automatic detection of Fake News. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07104 [ Links ]

Rateau, P., & Lo Monaco, G. (2016). La théorie structurale ou l'horlogerie des nuages. In G. Lo Monaco, P. Rateau, & S. Delouvée (Eds.), Les représentations sociales: théories, méthodes et applications (pp. 113-133). Louvain-la-Neuve: de Boeck. [ Links ]

Recuero, R., & Soares, F. (2020). O discurso desinformativo sobre a cura do COVID-19 no twitter: estudo de caso. Espaço e Economia, 1-26. doi: 10.1590/scielopreprints.84 [ Links ]

Reinert, M. (1990). Alceste, une méthodologie d'analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia de Gerard de Nerval. Bulletin de Methodologie Sociologique, 26(1), 24-54. [ Links ]

Resolução n. 510 (2016, April 07). Dispõe sobre as normas aplicáveis a pesquisas em Ciências Humanas e Sociais. Brasília, DF: Conselho Nacional de Saúde. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, J. N., & Azevedo, D. A. (2020). Pandemia do Coronavírus e (des)coordenação federativa: evidências de um conflito político-territorial. Espaço e Economia, 18, 1-11. doi: 10.4000/espacoeconomia.12282 [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L. (1973). La pensée sociale. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Introduction à la psychologie sociale, (pp. 299-327). Paris: Larousse. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L. (1975). Les rumeurs. Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L (1988). La psychologie politique. Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M. L. (1990). Le syndrome de rumeur. Communications, 52(1), 119-123. Retrieved from https://www.persee.fr/doc/comm_0588-8018_1990_num_52_1_1786 [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L. (1991). Rumeurs. In Grand dictionnaire de la Psychologie (pp. 683-684). Paris: Larousse. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L. (1994). Chaînes magiques, les maillons de l'appartenance. Neuchâtel: Delachaux et Niestlé [ Links ].

Rouquette, M.-L. (1997). La chasse à l'immigré. Violence, mémoire et représentations. Sprimont: Mardaga. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L. (1998). La communication sociale. Paris: Dunod. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M.-L., & Rateau, P. (1998). Introduction à l'étude des représentations sociales. Grenoble, France: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble. [ Links ]

Schulz, A., Wirth, W., & Müller, P. (2020). We are the people and you are fake news: A social identity approach to populist citizens' false consensus and hostile media perceptions. Communication Research, 47(2), 201-226. doi: 10.1177/0093650218794854 [ Links ]

Shimizu, K. (2020). 2019-nCoV, fake news, and racism. The Lancet, 395(10225), 685-686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30357-3 [ Links ]

Villela, D. A. M. (2020). The value of mitigating epidemic peaks of COVID-19 for more effective public health responses. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 53. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0135-2020 [ Links ]

We Are Social & Hootsuite (2020a). Digital 2020 April Global Statshot Report. Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-april-global-statshot [ Links ]

We Are Social & Hootsuite (2020b). Digital 2020 Brazil. Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-brazil [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020a). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020b, March). Virtual press conference on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-and-final-11mar2020.pdf?sfvrsn=cb432bb3_2.%20Acesso%20em:%2007%20maio%202020Â 108.pdf?sfvrsn=44cc8ed8_2.%20Acesso%20em:%2007%20maio%20202 [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2021, June 15). COVID-19 Weekly epidemiological update edition 44. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---15-june-2021 [ Links ]

Wolter, R. P., Wachelke, J., & Naiff, D. (2016). A abordagem estrutural das representações sociais e o modelo dos esquemas cognitivos de base: perspectivas teóricas e utilização empírica. Temas em Psicologia, 24(3), 1139-1152. doi: 10.9788/TP2016.3-18 [ Links ]

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. World Report. The Lancet, 395 (10225), 676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Espirito Santo

Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514

29075-910 - Vitória - ES, Brasil

Telefones: +55 27 4009-2501 / +55 (27) 3145-4571

Fax: +55 27 4009-2501

Email: rafaelpeclywolter@gmail.com

Received in 22.may.20

Revised in 22.jun.21

Accepted in 30.jun.21

Rafael Moura Coelho Pecly Wolter, Doutor em Psicologia Social pela Université Paris Descartes, Paris V, é Professor Titular-Livre da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS).

Flaviane da Costa Oliveira, Doutora em Psicologia Social pela Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS). Email: flavianecoliveira@gmail.com

Álvaro Rafael Santana Peixoto, Mestre em Psicologia Social pela Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Doutorando e bolsista FAPES no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS). Email: alvarorafael.peixoto@gmail.com

Thiago Rafael Santin, Mestre em Epistemologia pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Doutorando e bolsista CAPES no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS). Email: santin.thiago@gmail.com

Antonio Marcos Tosoli Gomes, Doutor em Enfermagem pela Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), é Professor titular da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Procientista da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/ Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ/FAPERJ) e pesquisador 1D CNPq. Email: mtosoli@gmail.com

Julia Ott Dutra, Graduação em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Residente no Programa de Saúde Mental do Instituto Capixaba de Ensino, Pesquisa e Inovação em Saúde (ICEPi). Email: juliaott_dutra@hotmail.com

Ana Clara Lopes Oliveira Reis, Graduanda em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS). Email: anaclaralor@hotmail.com

Heloisa Maria Silva e Silva Pinto, Graduanda em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES), Membro do Núcleo de Estudos de Práticas e Pensamento Social (PRAPS). Email: heloisamssp@gmail.com

1. In April 2020, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter were among the 14 most accessed social platforms worldwide, reaching about 3.8 billion people (We Are Social & Hootsuite, 2020a). In a January 2020 survey in Brazil, these virtual social networks were among the six most used (2nd, 4th and 6th, respectively). The most used, YouTube, was not included because we chose to exclude videos, WhatsApp (3rd), and Facebook Messenger (5th), because they are personal communication applications, making it impossible to collect public access posts (We Are Social & Hootsuite, 2020b).

![Informe sobre una Intervención de Salud Mental en la Pandemia de Covid-19 Basada en la Internet/title]](/img/es/next.gif)