Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

versión impresa ISSN 1413-294Xversión On-line ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.26 no.3 Natal jul./set. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20210023

10.22491/1678-4669.20210023

PSYCHOBIOLOGY AND COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

"And what lesson did the crow learn?" Children's understanding of fables

"E qual foi a lição que o corvo aprendeu?" A compreensão de fábulas por crianças

¿Y cuál fue la lección que aprendió el cuervo? La comprensión de los niños al respecto de las fábulas

Alina Galvão SpinilloI; Priscylla Emeline Silva DuarteII

IUniversidade Federal de Pernambuco

IIPsicóloga Clínica

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to research children's understanding of fables from a developmental perspective, seeking to identify the difficulties in relation to the moral lesson. Eighty children in the 1st and 3rd grades of Elementary School were individually asked to answer questions about a fable presented in audio format. One of the questions referred to the moral lesson. The answers to this question were analyzed qualitatively through a system of categories that expresses how children develop their understanding of the moral lesson. The data showed that the children of the 3rd grade performed better than those of the 1st grade. However, for both groups, the difficulty in understanding the moral lesson was relevant. The progression identified in the understanding of the moral lesson seems to be associated with the notion of detachment and generality in relation to what is conveyed in the text.

Keywords: understanding fables; moral lesson; children.

RESUMO

Este estudo investigou a compreensão de fábulas em crianças em uma perspectiva de desenvolvimento, procurando identificar as dificuldades em relação à lição moral. Oitenta crianças alunas do 1º e 3º ano do Ensino Fundamental foram individualmente solicitadas a responder perguntas sobre uma fábula apresentada em áudio. Uma das perguntas referia-se à lição moral. As respostas a essa pergunta foram analisadas qualitativamente por meio de um sistema de categorias que expressa como se processa o desenvolvimento da compreensão da lição moral. Os dados mostraram que as crianças do 3º ano apresentaram um desempenho melhor do que as do 1º ano. Contudo, em ambos os anos escolares foi marcante a dificuldade em compreender a lição moral. A progressão identificada na compreensão da lição moral parece estar associada à noção de afastamento e generalidade em relação ao que é veiculado no texto.

Palavras-chave: compreensão de fábulas; lição moral; crianças.

RESUMEN

Este estudio investigó la comprensión de las fábulas en los niños desde una perspectiva de desarrollo, buscando identificar las dificultades con relación a la moraleja. Se les pidió individualmente a 80 niños de 1º y 3º grado de escuela primaria que respondieran preguntas sobre una fábula presentada en formato de audio. Una de las preguntas se refería a la moraleja. Las respuestas a esta pregunta se analizaron cualitativamente a través de un sistema de categorías que expresa cómo se procesa el desarrollo de la comprensión de la moraleja. Los datos mostraron que los niños de 3º grado se desempeñaron mejor que los de 1º grado. Sin embargo, en ambos grados la dificultad para comprender la moraleja fue relevante. La progresión identificada en la comprensión de la moraleja parece estar asociada a la noción de distancia y generalidad con relación a lo que se transmite en el texto.

Palabras clave: comprensión de las fábulas; moraleja; niños.

Most studies carried out with children on the understanding of texts, both oral and written, examine this process through a particular type of text: stories. Although there is growing interest in other types of texts, such as argumentative (e.g., Almeida, Spinillo, & Lima, 2019; C. L. G. Coelho & Correa, 2017; Spinillo & Almeida, 2014) and expository (e.g., Çakir, 2008; Kendeou & Van den Broek, 2007; Ozuru, Best, Bell, Witherspoon, & McNamara, 2007), there is still a gap in the area regarding children's understanding of fables. The research on this type of text is characterized by two perspectives: one of an educational nature and the other of a psychological nature.

From an educational perspective, fables are didactic resources used to stimulate reading habits among students, develop language skills, critical thinking, creativity, and moral values (Rodrigues, Lima, & Martins, 2016). For example, Lima and Rosa (2012) report an experience carried out with Elementary School fifth graders. At first, students were asked to rewrite a fable presented by the teacher in their own words. In a second moment, they were asked to write their own fables. The authors positively assessed the experience, commenting on the importance of using fables as a didactic tool for the development of oral and written language.

A similar study was carried out by Elias and Greco (2012) with the objective of training critical readers through the reading of fables. The program, applied to Elementary School 6th graders, involved reading and interpreting fables, discussions, and reflections on the themes covered in them. The authors stressed the students' motivation when participating in the proposed activities, also stating that the intervention favored learning in general and critical reading of texts in particular.

The intervention proposed by Lima and Rosa (2012) focused on the written production of fables, and the intervention in the study conducted by Elias and Greco (2012) focused on reading and interpreting texts. Two points need to be considered regarding these studies. The first is that despite the positive comments from the authors about the improvements made by students, no assessments that could effectively indicate the nature and extent of these improvements were performed. Intervention studies are undoubtedly important tools either in education or in psychology. However, for the benefits of an intervention to be confirmed, methodological precautions are necessary, such as: assessing students before and after the intervention, making systematic assessments throughout the intervention, and comparing the performance of the students who participated in the intervention to those who did not participate (Spinillo & Lautert, 2008). The second point is that it is not known whether the mentioned improvements were specifically due to the use of the fable, or whether these improvements would not be equally obtained in relation to other texts. Possibly, the discussions and reflections conducted by the teacher were the element that provided improvements and not the fable per se. Based on these considerations, the role of the fable in promoting linguistic and cognitive skills needs to be further examined.

Ferreira (2015) applied a questionnaire to teachers from the first to the fifth grade of Elementary School about the context of reading in the classroom. The data revealed that teachers worked with fables in the classroom in the same way as they worked with other texts. According to the author, this non-differentiation is somewhat limiting, as it does not allow exploring the potential that fables present in leading the reader to consider different ways of thinking about human actions and values. In view of this, the author proposed a didactic sequence specifically aimed at fables that, however, was not implemented, and it is not possible to examine the gains that this sequence could have promoted. Once again, the need to systematically investigate possible improvements (cognitive, linguistic, social / moral) arising from the use of fables as a didactic resource is evident.

From a psychological perspective, studies specifically investigate the understanding of fables, treating them as an object of knowledge. Perim (2014), for example, examined the possible differences between genders. After watching the video of a fable, five students, 6-year-old Elementary School first graders, were asked to reproduce the text orally and answer questions. The answers given were not clarifying understanding, as they were analyzed based on parameters that dealt more with the preferences and identification of the participants with the characters of the fable than with the understanding of the text itself. The analysis of these reproductions suggested that there were differences between genders, as girls retold the fable in a more detailed way than boys. Due to the small number of participants, caution is needed when generalizing about possible differences between genders. In addition, providing more details about the text does not mean that there was a better understanding; just as the preferences of the participants and their identification with the characters of the fable also do not express the understanding about the text. It is also necessary to emphasize that none of the questions dealt with the moral lesson, which is the defining aspect of the fable. Thus, the results did not reveal much about children's comprehension.

However, there are studies that examine the understanding of the moral lesson, as is the case of research conducted by Narvaez, Bentley, Gleason, and Samuels (1998) with children from the third and fifth grades, and university students. Three tasks were used. In task 1, participants were asked to write a moral lesson for each story that had been presented. In task 2, after presented to three stories, children were asked to choose the one that best corresponded to each moral lesson presented. In task 3, the participants chose the moral lesson that best fit the story presented. There was an improvement in performance with as the participants' educational level got higher, both among children and between them and university students. Despite the progress identified between school grades, many children struggled to understand the moral lesson.

Goldman, Reyes, and Varnhagen (1984) investigated bilingual and monolingual children, from Early Childhood Education to the sixth grade of Elementary School. Three tasks were given: retelling the presented fables, answering questions about the characters' intentions, and to identify the moral lesson. It was observed that the path of development of the understanding of fables was similar between bilingual and monolingual children, and that until the fourth grade they had difficulties in understanding the moral lesson. The limited comprehension of the moral lesson was associated with explicit and specific aspects of the text.

Pelletier and Beatty (2015) carried out a research that involved two studies. In the first one, carried out with children from kindergarten through the sixth grade of Elementary School, the understanding of fables was investigated from a developmental perspective. After hearing a fable, the participants answered questions about facts, characters, and the moral lesson. Regarding the moral lesson, it was found that the youngest children tended to respond exclusively within the context of the fable, while the older ones provided more general answers that were not limited to the text. The second study examined the relationship between understanding fables and the theory of mind. This analysis was conducted only with children from Early Childhood Education who had participated in the first study. The data revealed that there are relations between the theory of mind and the comprehension of fables, since the understanding of the moral lesson involved the ability to identify the intentions and mental states of the characters.

Abrahansen and Sprouse (1995) compared children (10 to 13 years old) with and without learning difficulties regarding the understanding of the moral lesson of several fables. After listening to the reading of each text, the children chose, among four alternatives, the one that corresponded to the moral lesson, justifying their choice. Children without learning difficulties performed better than those with difficulties. These, even when they made the correct choice, were less adept at providing justifications, presenting explanations that had little to do with the text or that expressed a literal understanding of the moral lesson. The conclusion was that the figurative language typical of the moral lesson was a greater challenge for these children.

In a study aimed exclusively at understanding the moral lesson, Spinillo, Naschold, Marín, and Duarte (2020) interviewed children who were not yet literate, children in the literacy process, and literate children. The investigation consisted of analyzing a set of didactic situations presented during an intervention program aimed at developing students' reading and writing skills and in-service training for teachers. The focus was on the activities carried out with fables in the classroom, which generally consisted of teachers reading fables out loud, who then promoted discussions and comments about the characters and the narrated episodes. At the end of the activity, the students answered questions about the text. Only the answers to the question related to the moral lesson were analyzed, being classified into categories that allowed identifying a progression regarding the understanding of the moral lesson and the nature of the difficulties. The main result was that the moral lesson was a great challenge, especially for illiterate children and those in the literacy process who had difficulties to go beyond the context of the fable, that is, to attribute some degree of generality to what had been understood from the moral lesson.

Although exploratory, the study discussed, becomes relevant in view of the scarcity of investigations with Brazilian children that, from a psychological perspective, specifically examine the moral lesson. Actually, considering the moral lesson as a defining element of fables refers to a broader theoretical question: the relationship between text comprehension and textual genre. A number of studies show that textual structure and organization play an important role in comprehension. For example, in argumentative texts, it is essential to establish a relationship between points of view, justifications that support them, and the characters that defend them. In a study conducted by Almeida et al. (2019) with an argumentative text, the authors observed that children experience difficulties in relating a given point of view to a specific character in a text that presented different opinions on the same theme. In turn, causal relationships are difficult for children to understand in an expository text, rather than in narrative texts, as documented by Queiroz, Spinillo, and Melo (2021). Thus, as with argumentative and expository texts, it is necessary to consider the structure and organization of fables in order to examine how children understand this text.

Having animal characters with human behaviors and characteristics, fables are fictional narratives in which a conflict is established, with the main objective of transmitting teachings of a moral nature (N. N. Coelho, 2000; Fernandes, 2001). It is a short text, marked by dialogues usually established between two characters. In terms of structure and organization, fables consist of two parts, according to Portella (1983). The first part is about the episodes and actions of the characters, and the second one is about the moral lesson that is the element that sets it apart from other narratives. As such, it is crucial to examine the child's understanding of the moral lesson in research on the comprehension of fables.

Based on these considerations, the present study investigates the comprehension of fables in a developmental perspective, seeking to identify the specific difficulties that children face in trying to understand this type of text, paying special attention to the cognitive process of grasping the moral lesson. As an additional objective, this research aims to test the applicability of the analysis system developed in a previous exploratory study (Spinillo, Naschold, Marín, & Duarte, 2020). If its applicability is proven, the analysis system can be an important resource in future studies with Brazilian children. In general, the present investigation seeks to contribute to the literature in the area, especially in the Brazilian context, where fables have been usually considered in an educational perspective. In view of this, the present research is inserted in a psychological perspective, specifically in the scope of cognition.

Method

Participants

Eighty children of both genders, from middle class families, were equally divided into two groups: Group 1, formed by first graders (average age: 6 years and 2 months, SD: 3.41); and Group 2, formed by third graders (average age: 9 years and 1 month, SD: 4.46). These children had no intellectual, motor, or sensory limitations. Participation was voluntary, with the consent of their legal guardians, who signed the Consent Form. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pernambuco, Certificado de Apresentação para Apreciação Ética (CAAE, Presentation Certificate for Ethical Appreciation) protocol number 04864818.0.0000.5208.

Materials and Procedures

Participants were individually interviewed in a single session, recorded in audio. After listening, through an audio recording, to Aesop's fable (115 words) entitled "The fox and the crow" (Buchweitz, 2009), the children answered five questions presented in a fixed order (see Table 1). The fable is presented below:

Once upon a time there was a crow that ran away with a piece of cheese and decided to land on a tree.

The fox, seeing the crow with the piece of cheese, began to flatter him:

- How beautiful your feathers are!

Then he also spoke:

- How beautiful your body is! And if you had a voice, you would be superior to all birds!

The crow, hearing so much flattery, was very proud of himself and decided to lift his neck to sing. But when he opened his mouth, the piece of cheese fell off.

Then the fox, happily, ate the cheese. The crow was still hungry.

Moral of the story: there is nothing more treacherous than a flatterer. One must not be vain or rely on flatteries, as these can be false and self-serving.

Results

The data were initially analyzed according to the performance of the participants in the five questions, with a score of 0 for incorrect answers and 1 point for correct answers. Then a qualitative analysis was conducted, specifically on the answers provided to the question regarding the moral lesson of the fable.

Students' Performance on the Questions

Table 1 contains the questions presented to the participants and examples of correct and incorrect answers.

The percentage of correct answers among 3rd graders (71%) was significantly higher than first graders (56%), as revealed by the Chi-Square analysis (x² = 9.07; p = 0.00). The reason for this difference can be explained when comparing the performance of the different grades in each question, as shown in Table 2.

The Chi-Square detected significant differences between school grades only in relation to Q1 (x² = 4.52; p = 0.03) and Q5 (x² = 8.65; p = 0.00) since, in these questions, the performance was better among 3rd graders. It is worth mentioning the low percentage of correct answers in the question regarding the moral lesson (Q5), especially among first graders (5%). On the other hand, the percentage of correct answers in the question regarding the fox's intention (Q2) was equally expressive in both grades (first grade: 100%, and third grade: 97.5%). The relationship between these two results is summarized below.

According to Cochran's Q Test, the performance in the questions differed significantly among first graders (Q = 70.01; p <0.05) and third graders (Q = 51.40; p <0.05). As can be seen in Table 1, this was because for children in both grades, Q5 was significantly more difficult than the other questions, while Q2 was the easiest one. It appears, therefore, that the pattern of results was the same in the first and third grades: the moral lesson was difficult to understand, while the fox's intention was easy to be inferred.

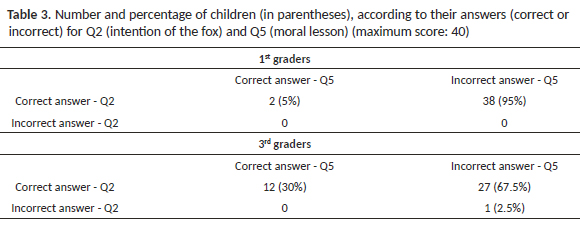

The difficulty with the moral lesson was, in fact, expressive. Only 14 of the 80 participants provided correct answers for Q5. Of these 14 children, two were first graders and 12 were third graders. On the other hand, as mentioned, children from both grades performed well in answering the question about the fox's intention. Considering these results, we tried to examine the relationship between understanding the fox's intention (Q2) and understanding the moral lesson (Q5), as illustrated in Table 3.

As can be seen, 95% of first graders gave incorrect answers to Q5, but gave correct answers to Q2. A similar result pattern was observed in the third grade, although in a less striking way, since most children (67.5%) gave incorrect answers to Q5 and gave correct answers to Q2. Apparently, understanding the fox's intention does not necessarily lead to a good performance in the question concerning the moral lesson. This intriguing result will be taken up in the final discussions, based on the findings derived from studies that examine the relationship between the comprehension of fables and the theory of mind.

In view of the relevance of the moral lesson for understanding fables and children's difficulties, it became relevant to conduct an analysis focused specifically on the answers provided to the question related to the moral lesson (Q5), as shown below.

Analysis of the Moral Lesson

The analysis of the answers provided to the question related to the moral lesson was based on the categorization proposed by Spinillo, Naschold, Marín, and Duarte (2020). The analysis was made by two blind and independent judges whose percentage of agreement was 71.2%. Disagreements were analyzed by a third blind and independent judge, with the majority prevailing. The categories in which these answers were classified are described and exemplified below:

Category 1 (vague): the child says he or she does not know or remember what lesson the character has learned, provides a vague answer, or no clear relation to the fable. Examples: "He learned to sing.", "He ... he lifted his neck, threw the cheese away, and ate it." and "Not to be beautiful."

Category 2 (passage): the child mentions a passage from the fable, be it an action by the characters or some particular episode. Examples: "Don't trust the fox." "That you're not supposed to sing with food in your mouth", and "Do not steal cheese on the sly".

Category 3 (opinion): the child gives an opinion about the characters or about an event. Unlike the answers in Category 2, that dealt with something that happened in the narration, the answer in this category expresses the child's understanding that it is necessary to issue some judgment or assessment about some character or about something that occurred in the narrative. Examples: "No ...do not ... open his mouth to talk to people he doesn't know." and "That you shouldn't open your mouth when you're eating."

Category 4 (recommendation): the child presents a recommendation that, although it is particularized in relation to the fable, has, unlike the answers in Category 3, a certain degree of generalization. Example: "That we should never brag about the things we have, because sometimes people can pretend to be good just to take what you have."

Category 5 (moral lesson): the child presents a recommendation of a moral nature that has a degree of generalization that goes beyond the fable. It is noted that in some cases the answer is not perfectly suited to the fable but indicates an approximate understanding of the text. In the case of the presented fable, mentioning false praising and vanity as essential elements. Examples: "That you shouldn't believe false praising.", "That we can't be vain." and "That some flattery can be false and deceive the person."

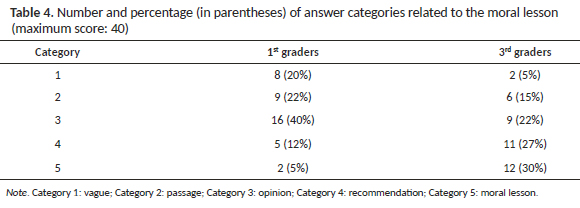

As can be seen, these categories are hierarchical, so Categories 1 and 2 are the most elementary ones, while Category 5 is the most elaborate one. Answers classified in Category 3 express the understanding that the moral lesson involves a certain distance from what is literally mentioned in the text, as they consist of a child's assessment of something that was narrated, not a repetition of what was narrated. Spinillo et al. (2020) comment that Category 3 means an improvement in understanding the moral lesson that, ultimately, involves a type of judgment of the situation presented in the fable. The answers classified in Categories 4 and 5 have a certain degree of generality, especially in Category 5. The distribution of these categories in each grade is shown in Table 4.

Due to the fact that there are cells with very low values, it was not possible to apply any statistical treatment to data referring to Q5. Thus, discussions about these results should be understood as trends.

As indicated in Table 3, regarding first graders, the answers were concentrated in Category 3, which expresses an opinion about a character or an event in the fable. On the other hand, in third graders, the answers were concentrated in Categories 4 and 5, which, respectively, are characterized by being a recommendation and by making a clear reference to the moral lesson. It is relevant to comment that the closest understanding that first graders reached about the moral lesson was to provide an opinion about the narrative. However, from a developmental perspective, it seems that formulating an opinion (Category 3) is an indication of a certain distance from the literal aspects of the text, which is an improvement towards understanding the moral lesson.

Discussion and conclusions

The comprehension of fables is still rarely explored topic in comparison to other types of texts, such as expository and argumentative ones. In Brazil, studies take a markedly educational perspective and have little empirical support, characterizing themselves as reports of experiences conducted in the classroom. Thus, there is a gap regarding the comprehension of fables in Brazilian children. Seeking to contribute to this field of knowledge, the present investigation adopted a psychological perspective, of cognitive nature, continuing and deepening a previous exploratory study. Two aspects were specifically addressed: how the development of the understanding of fables is characterized and what difficulties children face. A prominent role was given to the moral lesson, since it is considered a defining element of the fable.

Regarding development, two analyzes were conducted. One related to the general performance of the child from the first to third grades, and the other specifically aimed at understanding the moral lesson. Performance improvements, between first and third graders, were identified; but even with this improvement, the difficulty in understanding the moral lesson continued to be expressive, especially for first graders. This fact generated the need to carry out a specific analysis on this aspect, an analysis that was based on the system of categories of answers originally proposed by Spinillo et al. (2020) that allowed to identify how the development of moral lesson comprehension is processed. It was found that, initially, the child associated the moral lesson with some passage of the text, based on literal pieces of information conveyed in it. Then, it was noticed that the child understood that the moral lesson required to go beyond literal information, starting to issue an opinion about a character or episode narrated. Moving away from what has been narrated to assess what has been narrated is an improvement in the comprehension of fables. However, despite this improvement, the answers did not express a generalization, that is, an understanding about something that could be applied to other situations. The notion that something needs to be generalized was the next step in this process, which was expressed as recommendations about situations and actions that should or should not occur. It is important to mention that, while the answers of first graders expressed opinions, the answers of third graders, although with little clear association with the moral lesson, involved a recommendation that had a certain level of generality.

Thus, the progression identified regarding the comprehension of the moral lesson seems to be associated with the notion of distance and generality. This distancing refers to the need to distance oneself from what is literally presented in the text, and the generality to the notion that it is necessary to extract recommendations that can be applied to situations other than the one narrated in the text. These notions are also emphasized by Goldman et al. (1984), and by Pelletier and Beatty (2015) when they mention that young children tend to respond within the context of the narrative, while the older ones respond in a decontextualized way.

The study had the additional objective of examining the applicability of the analysis system developed by Spinillo et al. (2020). It seems that the categories that make up this system can be applied as a resource in the analysis of the understanding of the moral lesson by Elementary School children. This is a contribution to future research that adopts a developmental perspective, and to studies that assess the effectiveness of intervention programs in the context of understanding fables.

An intriguing result that should be commented on was the good performance observed in the question regarding the fox's intention in contrast to the great difficulty verified in relation to the moral lesson. Undoubtedly, understanding the intention of the characters is a fundamental aspect in understanding narratives (e.g., Gamannossi & Pinto, 2014; Shannon, Kameenui, & Baumann, 1988) and particularly in the comprehension of fables (Pelletier & Beatty, 2015). However, in the case of the present study, although the ability to identify the fox's intention was necessary to understand the fable, it was not enough to understand the moral lesson, specifically, given that the children were able to identify the fox's intention, but did not understand the moral lesson.

This result differs from that obtained by Pelletier and Beatty (2015). A possible explanation for this difference is because, in that study, comprehension was assessed through a general score, attributed to a set of questions about two fables, that was compared to the general score, obtained in an instrument that assessed the theory of mind. In the present study, however, the association between the ability to identify the intention of one of the characters and understanding the moral lesson was examined within the same instrument, noting that understanding the moral lesson was not associated with understanding the intention of the character (fox). However, this issue needs to be addressed in a future study that examines the ability to identify the intention, belief, and mental states of all the characters in the fable, and whether or not this ability would guarantee an understanding of the moral lesson.

Future research could also investigate, in children, what Dorfman and Brewer (2009) call 'basic components necessary to understand the moral lesson': (i) the negative or positive valence of the central episode of the fable, (ii) the positive or negative valence of the outcome of the fable, and (iii) the consistency between the valence of the central episode and its outcome. Another relevant aspect to explore would be the relationship between the moral lesson and the understanding of metaphors and proverbs, as highlighted by Jose, D'Anna, and Krieg (2005).

Other perspectives could be considered in studies on this topic. One would be to compare the comprehension of fables to the comprehension of other types of narrative texts such as stories. Another perspective would be to investigate the comprehension of fables through other methodological resources in addition to questions, for example, through the oral or written reproduction of the text. Experimental variations could also be explored in a research in which the child had to deal with different levels of explicitness of the moral lesson, such as, for example, verbalizing it spontaneously, choosing an alternative that corresponded to the moral lesson (see Abrahansen & Sprouse, 1995), or even interpreting the fable before and after reading the moral lesson (see Hanauer & Waksman, 2000).

Much remains to be investigated on this topic, and it is necessary to know the cognitive challenges that the child faces when trying to understand fables. This need is highlighted in the Brazilian scenario, given the lack of information derived from research with Brazilian children.

In conclusion, the result that points to the children's difficulty in understanding the moral lesson corroborates data documented in other investigations. In view of this, caution must be taken in assuming that reading fables to children ensures that they understand the moral lesson. We do not wish to state, as Narvaez et al. (1998) say, that fables cannot be read to children, but that they will undoubtedly give interpretations to the moral lesson very different from those that an adult individual would give. Unlike adults, children can give literal interpretations or even stick to details that are not associated with the moral lesson. The challenge from an educational point of view is to create didactic actions that make it possible to understand the characters' intentions and mental states, the causal relationships that permeate the characters' intentions and actions, and the moral lesson learned at the end of the text. Actually, this challenge requires going far beyond the mere reading of fables in the classroom, being essential the contribution of research that clarifies this phenomenon and that can adequately propose and test the effectiveness of classroom interventions.

References

Abrahansen, E. P., & Sprouse, P. T. (1995). Fable comprehension by children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28(5), 302-308. doi: 10.1177/002221949502800506 [ Links ]

Almeida, D. D., Spinillo, A. G., & Lima, I. D. M. (2019). Compreensão de texto argumentativo em crianças. Letras de Hoje, 54(2), 202-210. doi: 10.15448/1984-7726.2019.2.32158 [ Links ]

Buchweitz, D. (2009). Fábulas de Esopo. [S. L.]: Wkids. Rio de Janeiro: Ciranda Cultural. [ Links ]

Çakir, O. (2008). The effect of textual differences on children's processing strategies. Reading improvement. ProQuest Educational Journals, 45(2), 69-83. ISSN:0034-0510 [ Links ]

Coelho, C. L. G., & Correa, J. (2017). Compreensão de leitura: habilidades cognitivas e tipos de texto. Psico (Porto Alegre), 48(1), 40-49. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2017.1.23417 [ Links ]

Coelho, N. N. (2000). O conto de fadas: símbolos, mitos e arquétipos. São Paulo: DCL. [ Links ]

Dorfman, M. H., & Brewer, W. F. (2009). Understanding the points of fables. Discourse Processes, 17(1), 105-129. doi: 10.1080/01638539409544861 [ Links ]

Elias, S. M. E., & Greco, E. A. (2012). Leitura e compreensão de fábulas (Final article submitted to the Educacional Development Program, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Paraná). Retrieved from http://www.diaadiaeducacao.pr.gov.br/portals/cadernospde/pdebusca/producoes_pde/2010/2010_uem_port_artigo_sonia_maria_ercolin_elias.pdf [ Links ]

Fernandes, M. T. O. S. (2001). Trabalhando com gêneros do discurso: narrar fábula (Coleção trabalhando com gêneros do discurso). São Paulo: FTD. [ Links ]

Ferreira, R. L. (2015). Confabulando ideias de se trabalhar o gênero textual fábula em sala de aula: contribuições metodológicas (Master's Thesis, Universidade Norte do Paraná, Londrina). Retrieved from https://repositorio.pgsskroton.com/bitstream/123456789/837/1/Confabulando%20ideias%20de%20se%20trabalhar%20o%20 g%C3%AAnero%20textual%20f%C3%A1bula%20em%20sala%20de%20aula%20contribui%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20metodol%C3%B3gicas.pdf [ Links ]

Gamannossi, B. A., & Pinto, G. (2014). Theory of mind and language of mind in narratives: developmental trends from kindergarten to primary school. First Lang, 34, 262-272. doi: 10.1177/0142723714535875 [ Links ]

Goldman, S. R., Reyes, M., & Varnhagen, C. K. (1984). Understanding fables in first and second languages. NABE Journal, 8(2), 35-66. doi: 10.1080/08855072.1984.10668465 [ Links ]

Hanauer, D. I., & Waksman, S. (2000). The role of explicit moral points in fable reading. Discourse Processes, 30(2), 107-132. doi: 10.1207/ S15326950DP3002_02 [ Links ]

Jose, P. E., D'Anna, C. A., & Krieg, D. B. (2005). Development of the comprehension and appreciation of fables. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(1), 5-37. doi: 10.3200/ MONO.131.1.5-37 [ Links ]

Kendeou, P., & Van den Broek, P. (2007). The effects of prior knowledge and text structure on comprehension processes during reading of scientific texts. Memory and Cognition, 35(7), 1567-1577. doi: 10.3758/BF03193491 [ Links ]

Lima, R. M. R., & Rosa, L. R. L. (2012). O uso das fábulas no ensino fundamental para o desenvolvimento da linguagem oral e escrita. Revista de Iniciação Científica do Unilasalle, 1(1), 153-169. doi: 10.18316/cippus.v1i1.350 [ Links ]

Narvaez, D., Bentley, J., Gleason, T., & Samuels, J. (1998). Moral theme comprehension in third graders, fifth graders, and college students. Reading Psychology, 19(2), 217-241. Retrived from https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/0270271980190203 [ Links ]

Ozuru, Y., Best, R., Bell, C., Witherspoon, A., & McNamara, D. S. (2007). Influence of question format and text availability on the assessment of expository text comprehension. Cognition and Instruction, 25(4), 399-438. doi: 10.1080/07370000701632371 [ Links ]

Pelletier, J., & Beatty, R. (2015). Children's understanding of Aesop's fables: relations to reading comprehension and theory of mind. Frontiers in Psychology, 6:1448. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01448 [ Links ]

Perim, S. L. (2014). Compreensão de uma fábula por meninos e meninas de 6 anos: um estudo exploratório. Revista de Psicologia da UNESP, 13(2), 32-40. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pi-d=S1984-90442014000200004&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Portella, O. (1983). A Fábula. Revista Letras, 32, 119-138. doi: 10.5380/ rel.v32i0.19338 [ Links ]

Queiroz, J. T., Spinillo, A. G., & Melo, L. M. S. (2021). Compreensão de textos de diferentes tipos por crianças da Educação Infantil. Letrônica, 14(2), e38590. doi: 10.15448/1984-4301.2021.2.38590 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, M. S. F., Lima, J. M. D., & Martins, V. V. (2016). As fábulas no processo de alfabetização e letramento. Revista Mosaico, 7(1), 38-43. doi: 10.21727/rm.v7i1.108 [ Links ]

Shannon, P., Kameenui, E., & Baumann, J. (1988). An investigation of children's ability to comprehend character motives. American Educational Research Journal, 25, 441-462. doi: 10.3102/00028312025003441 [ Links ]

Spinillo, A. G., & Almeida, D. D. (2014). Compreendendo textos narrativo e argumentativo: há diferenças? Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 66(3), 115-132. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pi-d=S1809-52672014000300010&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Spinillo, A. G., & Lautert, S. L. (2008). Pesquisa-intervenção em psicologia do desenvolvimento cognitivo: princípios metodológicos, contribuição teórica e aplicada. In L. R. Castro & V. L. Besset (Eds.), Pesquisa-intervenção na infância e juventude (pp. 294-321). Rio de Janeiro: NAU. [ Links ]

Spinillo, A. G., Naschold, A., Marín, L. J. P., & Duarte, P. E. S. (2020). Um estudo exploratório sobre a compreensão de fábulas por crianças da educação infantil e do ensino fundamental. In O. C. Sousa, P. S. Ferreira, A. Estrela, & S. Esteves (Eds.), Investigação e práticas em leitura (pp. 128-150). Lisboa: CIED. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Alina Galvão Spinillo

Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Cognitiva

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, CFCH - 8o andar, Cidade Universitária

CEP 50.740-550, Recife, PE, Brasil

Telefone: +55 81 21268272/7330

Fax: +55 81 21267331

Email: alinaspinillo@hotmail.com

Received in 18.aug.20

Revised in 31.may.21

Accepted in 31.dec.21

Alina Galvão Spinillo, Doutora em Psicologia do Desenvolvimento pela Universidade de Oxford, Inglaterra, é Professora Titular da Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Cognitiva da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE). ORCID: 0000-0002-6113-4454

Priscylla Emeline Silva Duarte, Mestre em Psicologia Cognitiva pela Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), é Psicóloga Clínica. Email: priscyllaemeline_@hotmail.com. ORCID: 0000-0001-5653-3007