Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Temas em Psicologia

Print version ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.24 no.1 Ribeirão Preto Mar. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.1-23

ARTIGOS

Psychological interventions against workplace mobbing

Vanessa RissiI; Janine Kieling MonteiroII; William Weber CecconelloIII; Eliz Graciela de MoraesIV

IDepartment Head of Graduate Studies in Psychology, Meridional College IMED, Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil. Graduate Program in Clinical Psychology, Vale do Rio dos Sinos University, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil

IIGraduate Program in Clinical Psychology, Vale do Rio dos Sinos University, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil

IIIGraduate School of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

IVMeridional College IMED, Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Workplace mobbing is a global phenomenon with a complex and multicausal nature. This concept refers to violent behaviors which aim to humiliate, exclude and cause psychological damage to an individual or group in the work environment. Since workplace mobbing may cause or exacerbate several psychological disorders, it must be addressed by psychological interventions. In light of these concerns, the aim of this article was to investigate whether psychologists in organizational settings address the issue of mobbing, and describe the interventions implemented in this type of situation. We also sought to investigate their understanding of the concept of mobbing in the workplace. This was a qualitative exploratory study involving seven psychologists recruited by convenience. Participants were interviewed, and data were processed by content analysis. Our findings showed that psychologists make use of specific and isolated preventive interventions, as well as reactive interventions, such as maintaining a physical distance between the parties involved in mobbing and monitoring the behavior of the offender. It was also observed that psychologists adequately understand bullying as a phenomenon characterized by humiliation, which is often perpetrated by managers, as a form of abuse of power.

Keywords: Mobbing, psychological interventions, prevention, work.

Workplace mobbing is a serious and complex problem rooted in social, economic, organizational and cultural factors. This is a global phenomenon, which has concerned academics from diverse disciplinary backgrounds as well as international organizations involved in worker protection and human rights (Heloani & Barreto, 2010). Although workplace mobbing has been discussed in the international literature for over 25 years, it has been studied for significantly less time in Brazil (Soboll, 2008a): the first article on the topic was only published in 2001. This type of psychological violence is often underestimated by organizations (Guimarães & Vasconcellos, 2012). However, it has been present in Brazil since colonial times (Teixeira, Munck, & Reis, 2011).

Mobbing refers to abusive, intentional, and frequent attempts to shame, humiliate, and devalue an individual or group, degrading their working conditions and threatening their personal and professional integrity (Freitas, Heloani, & Barreto, 2008; Leymann, 1996).

Workplace mobbing is characterized by four major features, all of which have been previously discussed by Freitas et al. (2008), Rezende (2008) and Soboll (2008b):

1. Frequency and recurrence: hostile behaviors must occur several times a day, for a certain period of time. Isolated instances are not considered mobbing. There is no consensus on the usual duration of mobbing, but occurrences must be continuous and persistent to be classified as such.

2. "Personalness": ho stile behaviors are not directed at a group of people, but at a specific person. It is possible for more than one person in a particular group to be targeted, but the process is always direct and personal.

3. Geographical limit: hostile behaviors must occur in the workplace, among people who are employed or depend directly or indirectly on the same organization.

4. Intention to harm: the behaviors in question intend to harm the victim so as to reduce their acting space and force their removal from the organization or a specific project in which (s)he is involved. The target can be defined either explicitly or implicitly.

According to the World Health Organization (Organización Mundial de la Salud [OMS], 2004), psychological abuse may cause or contribute to the appearance of several psychopathological, psychosomatic and behavioral disorders. The individual, organizational and social consequences of mobbing have been investigated by several international studies, and include impairments in victim quality of life (Niedl, 1996); suicíde, post-traumatic stress disorder (Hansen et al., 2006); problems in family relationships (Duffy & Sperry, 2007); decreased work satisfaction (Hoel & Cooper, 2000); interpersonal problems in the workplace (Vega & Comer, 2005); impaired group processes and increased aggressive behaviors (Ramsay, Troth, & Branch, 2010); impairments in cognitive functions such as attention and concentration, and an increased risk psychological disorders such as depression (International Labor Organization [ILO], 2000; OMS, 2004) increased medical costs and early retirement (Hoel, Sparks, & Cooper, 2001). On a similar vein, Freitas (2007) identified several consequences associated with workplace mobbing in Brazil, ranging from victim psychopathology at an individual level, to decreased productivity and increased social security spending, at organizational and social levels, respectively. Suicide may also result from psychological harassment (Freitas, 2011).

Most researchers divide workplace harassment into four major types: downward (or vertical), upward, horizontal, and mixed. Hirigoyen (2005a) defines downward harassment as abuse by a superior. This is usually the most common type of harassment. Horizontal harassment involves abuse by a colleague of the same hierarchical level. This type of abuse often occurs when workers compete for the same job or promotion. A less common type of abuse is upward harassment, in which a manager is attacked by one or more subordinates. This usually occurs when a new worker is hired for a managerial position in an organization. Other employees who wanted the job may then dispute the authority of the new hire. Mixed harassment occurs when an employee is attacked by individuals across different hierarchical levels, such as colleagues and superiors. Regardless of the type of harassment (downward, mixed, horizontal or upward), workplace mobbing is a complex process in which the victim is often unable to defend themselves. This may have significant repercussions for their self-esteem. The loss of self-concept, combined with a feeling of uselessness, may result in a loss of dignity and self-respect (Heloani & Barreto, 2010).

Workplace mobbing can involve two distinct pathways: personal harassment, which is related to interpersonal relationships, and organizational harassment, which is associated with the organizational context, process and management (Soboll, 2008b). Therefore, when investigating workplace mobbing, it is important to evaluate both workplace relationships and the organization itself.

Both employers and employees recognize that psychological abuse is a severe form of violence, which may result from changing dynamics in the relationship with colleagues and superiors. Organizational relationships are increasingly dominated by individuality and competitiveness; rather than encouraging bonding and cooperation between workers, they prevent employees from recognizing and valuing the work of others. Under such circumstances, there may be a belief that events are not caused by injustice, but rather, by economical or systemic factors, or even by destiny alone (Dejours, 2001). As a result, situations of violence may become a natural and banal part of the organizational routine, with the organization often emphasizing their supposed economical and systemic causes to rid itself of responsibility (Monteiro & Machado, 2010). This explains the position of most organizations towards situations of violence, as well as the near nonexistence of company records of psychological abuse or workplace mobbing.

Work-related psychological disorders and complaints pose a great challenge to occupational health professionals (Glina & Rocha, 2010), including psychologists. Psychological interventions are equipped to prevent and treat a variety of problems, as well as promote mental health (Capitão, Scortegagna, & Baptista, 2005) across several contexts, and could be adapted to the issue of workplace mobbing, precisely due to its contribution to psychological suffering and ill health.

Several publications have described interventions to prevent and/or combat mobbing, or promote mental health in the workplace. On the other hand, few studies have assessed the efficacy of such interventions (Glina & Soboll, 2012). According to the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2009a), mobbing is a psychosocial risk factor, and, as such, must be addressed by interventions which follow general guidelines for risk assessment and management in the workplace.

Interventions to improve the psychological climate at work are recommended and necessary (Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf, & Cooper, 2003). These interventions may be divided into three types according to their target: individuals who are directly involved in the issue (aggressors and victims), the individual-organization interface (departments, teams and groups of colleagues), or the organization itself.

Workplace mobbing can be prevented in several different ways. Potentially useful interventions include educational programs for employees and managers regarding appropriate workplace social norms, as well as limit-setting interventions. Preventive measures must also include awareness-raising among employees, discussion groups, and adequate training for human resource professionals (Hirigoyen, 2005b).

According to the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2009b), the following measures may help prevent workplace mobbing: (a) leave workers free to choose how to do their job; (b) disseminate organizational goals; (c) develop employee leadership skills; (d) clarify job and task descriptions; (e) develop organizational policies which foster positive professional relationships; (f) establish programs and policies to identify and manage these problems inside the organization.

Possible interventions for victims of workplace mobbing include counseling, support groups, rehabilitation and return-to-work strategies, and the establishment of ombudsman services (Glina & Soboll, 2012). According to Tehrani (2003), such interventions should be implemented by professionally trained counselors. Some other useful interventions suggested by this author include debriefing, narrative therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, other types of psychotherapy and self-help groups.

The present study was motivated by the idea that the professional duties of the organizational psychologist include the management of workplace mobbing. According to articles I and II of the Code of Professional Ethics in Psychology (Conselho Federal de Psicologia [CFP], 2005), psychologists must work to promote respect, freedom, dignity, equality and human integrity, and uphold the values expressed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, always seeking to enhance health and quality of life at individual and group levels, contributing to the elimination of any type of neglect, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty and oppression. Similarly, the National Guidelines on the work of psychologists in Brazil (CFP, 1992) state that the respect of human dignity and integrity must always underlie the professional practices of these individuals.

In light of these concerns, the aim of this article was to investigate whether psychologists in organizational settings address the issue of mobbing, and describe the interventions implemented in this type of situation. We also sought to investigate their understanding of the concept of mobbing in the workplace.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited by convenience, according to the following inclusion criteria: psychologists who had worked for at least one year in the same organization. The sample included seven female psychologists with a mean age of 31 years, with an average of seven years since graduation. They had worked at their current job for a mean of six years, and 66.66% of the sample had graduate-level training in organizational psychology and/or human resource management. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1.

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews based on a standard guide. The interview was divided into three main sections: understanding of workplace mobbing; perceived occurrence of mobbing situations; and interventions used to address the issue. Participants were interviewed at work at a previously scheduled time. Data were collected between September and November 2013. Interviews had a mean duration of 60 minutes, and were fully recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

All interviews were subjected to content analysis, according to the method proposed by Bardin (1979): pre-analysis, classification or categorization, and interpretation.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution in which it was performed under project number 11424812.8.0000.5319. All subjects provided written consent for participation, as recommended by ethical guidelines for human research.

Results and Discussion

Data analysis revealed three consistent themes across participant interviews, all of which pertained to the aims of our research: (a) workplace mobbing: humiliation and abuse of power; (b) perceptions of the occurrence of workplace mobbing; (c) preventive and reactive psychological interventions.

Mobbing: Humiliation and Abuse of Power

The interviewees understood mobbing as an inappropriate relational pattern, characterized by insults, humiliation, and aggression. This definition is similar to that reported in the literature. In the words of Subject A: ''It's a situation in which someone is being victimized, and feeling humiliated, exposed, and which can cause psychological harm due to the exposure to embarrassing situations". Furthermore, participants tended to associate harassment with aggressive behavior by managers, which suggests that downward harassment may be more common than other types of abuse in these organizations.

Glina and Soboll (2012) describe mobbing as a negative behavior which constitutes an extreme form of psychological violence, which causes embarrassment to the victim (Soboll, 2010). Hirigoyen (2005b), who is responsible for the worldwide dissemination of the concept of mobbing, defines it as any and all abuse which manifests especially in the form of behaviors, words, acts, gestures, and writings, and harms the personality, dignity or the physical and psychological integrity of the individual, putting their job at risk or degrading their work environment.

Psychologists understood mobbing as a type of abuse which is most commonly perpetrated by hierarchical superiors on their subordinates. This situation can also constitute an abuse of power, as described by Subject G, ''It is a situation provoked by hierarchical superiors on their subordinates'' and Subject C: ''Mobbing is anything that denies the respect for employees, like whenever people end up using, for instance, their own position of leadership to get things for themselves''.

Workplace mobbing is known to be strongly associated with aspects of the work environment and organization, such as styles of leadership (Einarsen, 2000). The competitiveness which permeates the organizational environment may intensify situations of harassment. These conditions foster the noxious treatment of subordinates by superiors, who use their power to reject or humiliate other workers. Not infrequently, these individuals are seen as efficient administrators by their superiors, due to their assertive and aggressive nature (Heloani, 2003).

Exacerbated competitiveness, as well as destructive and tyrannical leadership styles, all of which were mentioned by the interviewees as part of workplace relationships, are indicative of a type of organization which is conducive to situations of workplace violence, such as mobbing. These observations suggest that work organization is a fundamental dimension of the understanding of violent workplace situations which result in suffering. The concept of work organization (Dejours, 1988; Mendes, 2007) refers to biopsychosocial characteristics of work, such as the division of labor, affective and socioprofessional relationships, work conditions, initiative and autonomy, the ambiguity of task outcomes, as well as the level of cooperation and communication. Depending on its characteristics, the work organization can influence the development of work relationships characterized by competition and individualism as opposed to positive socioprofessional relationships, setting the stage for workplace mobbing. Martiningo and Siqueira (2008) illustrated this concept by demonstrating that certain forms of work organization cause insecurity in managers and subordinates, placing them under intense pressure to achieve set targets and objectives without adequate organizational support. Under these circumstances, they become more likely to engage in mobbing behaviors.

When discussing workplace mobbing, the psychologists interviewed for the present study did not appear to establish a relationship between violent and disrespectful leaders and the organization itself, although, as previously mentioned, certain organizational features may facilitate or even encourage workplace mobbing. The phenomenon which results from this situation can be referred to as organizational harassment (Soboll, 2008a).

Although the psychologists interviewed were familiar with the concept of mobbing, none of them referred to the features used to identify these behaviors, such as their frequency and duration. Although there is no consensus as to the average frequency and duration of these phenomena (Glina & Soboll, 2012), these characteristics are fundamental for the identification of mobbing behaviors, and for the differentiation between this and other forms of workplace violence (Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996).

Perceptions of Workplace Mobbing

Most of the subjects interviewed denied the occurrence of mobbing in the company for which they work. Subject D, for instance, made the following statement: ''I would like to say it doesn't, and I believe it doesn't happen. We never had any problems with mobbing". Similarly, Subject F said, ''Well, I don't believe so, although I speak for only one side, for the psychology department, for the administration... but it seems to me that it doesn't''. These statements suggest that some companies may be able to maintain healthy workplace relationships with the help of work organization practices which contribute to the absence of workplace harassment and other forms of violence. Many organizations have decided fight workplace mobbing through interventions such as zero-tolerance policies for harassment (Salin, 2008), codes of ethics, and mechanisms to encourage the reporting of incidents to human resources (Heloani, 2005).

Unfortunately, much of what was said by the psychologists interviewed for the present study was followed by justifications and denial, in an attempt to defend the image of the company, and probably, their own work as psychologists, as illustrated by Subject F: ''It is possible for a manager to go overboard with a worker, but on the other hand, we see the opposite thing also, some workers who go looking for it, who provoke this type of situation" and Subject D:

Mobbing doesn't happen here. It all depends on the person. The other day I heard someone say that their boss told them to join Weight Watchers, since they would be more productive if they lost weight. So it all depends on the person being psychologically prepared to deal with that. It doesn't necessarily make it harassment.

In both cases, the worker was said to be responsible for the embarrassing situation to which they were exposed. Unfortunately, workplace mobbing is often blamed on the victim (Hirigoyen, 2005b) due to supposed personality issues or emotional fragility, as has been studied by Vartia (1996). However, the personality of the victim is known to have little bearing on the cause of workplace mobbing (Leymann, 1992), since these incidents are far more likely to be prompted by organizational and psychosocial factors, as has been discussed earlier in this article.

Victim-blaming for incidents in the workplace is still a common practice among administrators and organizational psychologists. Occupational psychodynamics provides some conceptual reflections on the topic in an attempt to understand why workers are so frequently blamed for situations in which they are usually the victims, as is the case of mobbing. According to Barros (2010), by neglecting the practical aspects of a task and its demands on the worker (that is, considering management objectives only), organizations deceive themselves into the believing that workers are incapable, unprepared, unqualified, or unequipped for work. This perspective shifts the focus of attention to the individual worker and neglects the complexity of human behavior and the situations faced by this individual in the web of organizational culture. The power of the workers is curbed by the work organization, which prevents their activity. In this situation, if we focus on management objectives only, we are likely to blame the worker for their lack of productivity (Barros, 2010).

One of the psychologists interviewed did acknowledge the existence of mobbing in their company. According to Subject B,

There was one situation in which an older director was calling the phone operator a witch, and saying he was going to buy her a broomstick as a gift. So, she was feeling humiliated and I had to intervene. He had been in the company for 30 years, and she had only been there for one. She was still having trouble adjusting to his rapid pace.

In this case, it appears that the aim of the abusive behavior was to manage worker productivity, since this individual could not follow the work pace imposed by the company (Andrade & Tito, 2012). This situation illustrates the concept of organizational mobbing, which has already been discussed by Brazilian researchers (Araújo, 2006; Soboll, 2006, 2008b), and refers to the use of abusive behaviors as means to manage, control and discipline, and not just harm the worker, as is the case of typical mobbing.

Preventive and Reactive Psychological Interventions

Preventive interventions against mobbing and workplace violence can be classified as primary, secondary or tertiary. Primary interventions consist of risk assessment and reduction, as well as the introduction of anti-harassment policies. Secondary interventions involve qualification programs, worker surveys, and conflict resolution. Lastly, tertiary prevention involves harm reduction and treatment once the incident has already occurred (Leka & Cox, 2008).

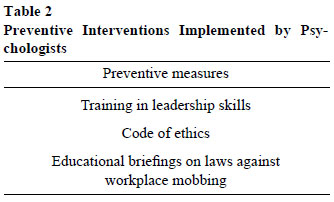

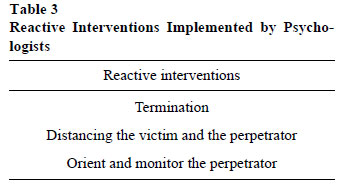

The psychologists interviewed mentioned both preventive and reactive interventions, as summarized in Tables 2 and 3. In the present study, reactive interventions are defined as any and all measures implemented by psychologists when mobbing has already occurred, or is likely to occur.

Although the psychologists implemented several preventive initiatives, none of them focused exclusively on mobbing, as explained by Subject D: "There is qualification and development, but nothing focused specifically on mobbing".

However, there appeared to be a general concern about ensuring leaders were trained in the skills required to establish respectful relationships with subordinates, through assertive communication and feedback techniques, as discussed by Subject A: ''What we do is implement manager development initiatives in which we talk about many things, such as what to say to subordinates, how to say it, how to handle terminations''.

This type of initiative is discussed by Terrin (2007), who suggests that workplace mobbing should be addressed by the reevaluation of company values and a change in the organizational culture, which should include the incentive of constant and permanent interpersonal communication. Policies regarding individual well-being, conflict mediation, training and development, as well as the formation of a positive organizational climate may not only resolve the occasional problem, but also contribute to the establishment of a healthier work environment, with no ambiguity or doubt (Heloani & Barreto, 2010).

The creation of a code of ethics was also used as a preventive strategy, as explained by Subject B ''We have a code of ethics regarding respect, social equality, how to demand results from collaborators, and the types of behavior which are not allowed in the company''.

However, workplace mobbing is never specifically mentioned in the codes of ethics cited. This is a cause for concern, since codes of ethics should, ideally, contain explicit descriptions of behavioral norms and expectations, to ensure that any behaviors not tolerated by the organization are clearly defined (Martiningo & Siqueira, 2008). Additionally, it is important to note that the presence of a code of ethics does not relieve the company of responsibility for any inadequate behaviors which may occur.

Some researchers have gone further in their study of preventive actions, and attempted to discuss their efficacy. These studies have identified some fundamental elements of preventive interventions, such as the promotion of a positive social climate which values diversity and addresses frustration and conflicts, the adoption of egalitarian management styles, and the development of a work organization based on clearly defined goals, rules and responsibilities (Freitas et al., 2008).

The implementation of activities, policies or procedures to address workplace mobbing did not appear to be common practice among the organizational psychologists interviewed in the present study. However, legal training, usually conducted by lawyers, appeared to be somewhat common in the companies analyzed, as reported by Subjects D, ''Labor claims always expose the company. It is important to discuss the legal impact suffered by the company through debates and discussions with lawyers'' and G: "Our lawyer gives talks about legal issues, and how they are handled by the Ministry of Labor. We focus far more on orientations to avoid labor suits. This is one of the prevention tools we use".

Workplace mobbing can certainly result in labor claims due to their potential to cause psychological harm. The company must always be held responsible for this type of incident regardless of the hierarchical status of the perpetrator. In legal terms, the psychological harm caused by workplace mobbing represents the damage suffered by the victim of this type of offense. If there is evidence of psychological harm, the victim is eligible to receive financial compensation (Carvalho & Tonial, 2012). The interviews demonstrated that this may be a greater concern for companies than the psychological and emotional repercussions of mobbing, as discussed by Subject G:

There was one supervisor who talked too much when asking workers about their goals. The department even filed a complaint. It wasn't very serious, but we were still worried. We can't encourage this type of thing. If we do, sooner or later we will have trouble with the law.

These findings agree with those of Argimon, Boaz, Da Rosa, Daldon and Wendt (2007), who found that psychologists are increasingly moving away from a humanized perspective, and submitting to the demands of the company and administration. Even those who realize that their actions are no longer aligned with their professional goals may end up adhering to the perspective of the organization.

The code of professional ethics issued by the CFP (2005) states that psychologists must always seek to promote health and quality of life at individual and collective levels, and contribute to the elimination of any form of neglect, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty and oppression. This suggests that to abstain from the search for answers, and maintain an accessory silence and a position of conformity to ongoing suffering in the company goes against psychologists' professional obligations (Caniato & Lima, 2008).

The termination of the aggressor was cited as a possible response to a mobbing incident by Subject B: ''If it did happen we would certainly opt for termination. Since this is a family company, built on respect and ethics, we would have no choice other than termination''.

Another possible intervention would be to distance the victim from the aggressor, as suggested by Subject E: ''We would ask the manager to avoid direct contact with the victim, and tell her to do the same''.

Both interventions are only palliative. The conflict will remain latent and may resurface at a later time. When the situation is addressed by distancing the parties involved, it is important to consider that harassment may still persist in organizations which implicitly authorize it, as suggested by Brodsky (1976). The absence of sanctions against those who do not follow the rules or break anti-harassment policies may give this impression to employees. Interviews with victims of workplace mobbing have revealed that this phenomenon tends to occur in companies whose organizational culture permits or encourages this type of behavior (Einarsen, Skogstad, Raknes, & Matthieses, 1994).

Another intervention cited by psychologists was to talk to the perpetrator and request a change in behavior, as suggested by Subject F:

We ask him to go to the HR department. This is when we talk about what is happening and give the necessary orientations to the worker. We explain that we cannot tolerate this type of behavior and set a deadline for his change in attitude.

Crawshaw (2008) has described coaching methods specifically designed for the rehabilitation of abrasive leaders through the use of empathy. This author interprets harassment as a maladaptive response to perceived threat. However, this type of intervention has been less explored by research.

The present findings cannot speak to the effectiveness of interventions involving the victims of psychological abuse, given that most interviewees denied the occurrence of harassment in their respective companies. However, according to the national and international literature (Glina & Soboll, 2012; Sheehan, 1999), workplace mobbing has become an increasingly common phenomenon due to the changing dynamics and pressures of the working world. As such, we cannot refrain from discussing the different types of interventions involving the victims of mobbing.

The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2002) refers to these initiatives as individual interventions, since they seek to improve the worker's ability to deal with stress. Examples of such interventions include counseling, support groups, rehabilitation and return-to-work strategies, as well as ombudsman services (Glina & Soboll, 2012). Professionally-trained counselors may also be helpful, as demonstrated by Tehrani (2003). This author also suggests the use of debriefing, narrative therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, other types of psychotherapy and self-help groups.

However, preventive measures are significantly more important than any interventions performed after mobbing has already taken place, as discussed by Heloani (2011), who also stresses the importance of holding the company accountable. The prevention and protection against mobbing prevents such practices from becoming institutionalized, and therefore, accepted or naturalized.

Final Considerations

Psychological interventions against workplace mobbing are usually performed on a case-by-case basis rather than as part of a larger initiative to combat this phenomenon. There appear to be no preventive interventions in place which specifically target mobbing. However, the development of initiatives such as feedback training for managers suggests that the professionals interviewed understand the importance of preventive action.

The psychologists interviewed also suggested several possible strategies to deal with mobbing once it has already occurred, including termination, distancing of the parties involved, and the provision of orientations to the aggressor. Unfortunately, isolated and sporadic interventions are known to be ineffective, since they fail to consider psychosocial variables such as the organizational climate and culture (Glina & Sobol, 2012).

The psychologists interviewed described workplace mobbing as an act of violence characterized by humiliation and embarrassment. They also suggested that downward mobbing, or the abuse of subordinates by a superior, was more common than other forms of psychological abuse.

The role of the psychologist in workplace mobbing should be more rigorously questioned, especially since, according to the professional code of ethics (CFP, 2005), it is his duty to combat situations of violence, discrimination or negligence. Given the magnitude of this phenomenon, it is imperative that all possible efforts be made to control it, either by preventive interventions, or by secondary and tertiary measures. Are psychologists succumbing to the interests of the organization and administration? That is the question posed by this research.

We therefore suggest that future studies engage in a critical reflection on the role of the organizational psychologists. Given the limitations of the present study, especially the fact that these data may not be representative of the category as a whole, we emphasize the need for further discussion of the effectiveness of psychological interventions against workplace mobbing in the Brazilian population. Similarly, the small number of psychologists interviewed may have biased our results, especially since nearly all participants denied the occurrence of mobbing in their companies.

References

Andrade, J. A. D., & Tito, F. R. D. C. (2012). Estruturação intersubjetiva do assédio moral: Um estudo do contexto das organizações bancárias. Revista Organizações em Contexto, 8(15),1-20. doi:10.15603/1982-8756/roc.v8n15p1-20 [ Links ]

Araújo, A. R. (2006). O assédio moral organizacional (Dissertação de mestrado em Direito, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, SP, Brasil). [ Links ]

Argimon, I. I. D. L., Boaz, C., Da Rosa, H. D. L. R., Daldon, K. A., & Wendt, G. W. (2007). O profissional da psicologia nas organizações: A significação dos valores empresariais no trabalho na psicologia. Revista de Ciências Humanas, 8(11),107-126. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1979). Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa, Portugal: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Barros, V. A. (2010). O trabalho do profissional psicólogo: Construindo uma posição crítica. In Conselho Federal de Psicologia (Ed.), Psicologia crítica do trabalho na sociedade contemporânea (pp. 57-104). São Paulo, SP: Conselho Federal de Psicologia. [ Links ]

Brodsky, C. M. (1976). The harassed worker. Toronto, Canada: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Caniato, A. M. P., & Lima, E. da C. (2008). Assédio moral nas organizações de trabalho: Perversão e sofrimento. Cadernos de Psicologia Social e do Trabalho, 11(2),177-192. doi:10.11606/issn.1981-0490.v11i2p177-192 [ Links ]

Capitão, C. G., Scortegagna, S. A., & Baptista, M. N. (2005). A importância da avaliação psicológica na saúde. Avaliação Psicológica, 4(1),75-82. [ Links ]

Carvalho, S. A., & Tonial, J. C. (2012). A prova do assédio moral no ambiente de trabalho. UNOPAR CIENTÍFICA: Ciências Jurídicas e Empresariais, 13(1),13-22. [ Links ]

Conselho Federal de Psicologia. (1992). Sobre a profissão: Atribuições profissionais do psicólogo no Brasil. Brasília, DF: Autor. Recuperado em http://www.crprs.org.br/download/atr_prof_psicologo.pdf [ Links ]

Conselho Federal de Psicologia. (2005). Código de ética profissional do psicólogo. Brasília, DF: Autor. Recuperado em http://site.cfp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/codigo_etica.pdf [ Links ]

Crawshaw, L. (2008). Rehabilitating abrasive leaders through executive coaching & organizational intervention. Proceedings of the Conference Internationale sur le Harcelement Psychologique/Moral au Travail, 6,147. [ Links ]

Dejours, C. (1988). A loucura do trabalho: Estudo de psicopatologia do trabalho. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Dejours, C. A. (2001). Banalização da injustiça social (4. ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fundação Getúlio Vargas. [ Links ]

Duffy, M., & Sperry, L. (2007). Workplace mobbing: Individual and family health consequences. The Family Journal, 15(4),398-404. doi:10.1177/1066480707305069 [ Links ]

Einarsen, S. (2000). Harassment and bullying at work: A review of de Scandinavian approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(4),379-401. [ Links ]

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). The concept of bullying at work: The European tradition. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace (pp. 3-30). London: Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from http://ir.nmu.org.ua/bitstream/handle/123456789/129149/2e5cd9e115eff61cb563d6c97714791a.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2),185-201. doi:10.1080/13594329608414854 [ Links ]

Einarsen, S., Skogstad, A., Raknes, B. I., & Matthieses, S. B. (1994). Bullying and harassment at work and their relationships to work environment quality. The European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 3,381-401. doi:10.1080/13594329408410497 [ Links ]

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2002). How to tackle psychosocial issues and reduce work-related stress. Systems and Programmes. Retrieved from http://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/reports/309 [ Links ]

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2009a). OSH in figures: Stress at work - Facts and figures (European Risk Observatory Report No. 9). Retrieved from https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/TE-81-08-478-EN-C_OSH_in_figures_stress_at_work [ Links ]

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2009b). Workplace violence and harassment: A European Picture (European Risk Observatory Report). Retrieved from https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/reports/violence-harassment-TERO09010ENC [ Links ]

Freitas, M. E. de. (2001). Assédio moral e assédio sexual: Faces do poder perverso nas organizações. RAE - Revista de Administração de Empresas, 41(2),8-19. doi:10.1590/S003475902001000200002 [ Links ]

Freitas, M. E. de. (2007). Quem paga a conta do assédio moral no trabalho? RAE - Eletrônica, 6(1). doi:10.1590/S1676-56482007000100011 [ Links ]

Freitas, M. E. de. (2011). Suicídio: Um problema organizacional. GV Executivo, 10(1),54-57 [ Links ]

Freitas, M. E., Heloani, J. R., & Barreto, M. (2008). Assédio moral no trabalho. São Paulo, SP: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Glina, D. M. R., & Rocha, L. E. (2010). Saúde mental no trabalho: Da teoria à prática. São Paulo, SP: Roca. [ Links ]

Glina, D. M. R., & Soboll, L. A. (2012). Intervenções em assédio moral no trabalho: Uma revisão da literatura. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional, 37(126),269-283. doi: 10.1590/S030376572012000200008 [ Links ]

Guimarães, L. A. M., & Vasconcelos, E. F. (2012). Mobbing (assédio psicológico) no trabalho: Uma visão crítica contemporânea. Revista Psicologia e Saúde, 4(1),85-93. [ Links ]

Hansen, Å. M., Hogh, A., Person, R., Karlson, B., Garde, A. H., & Ørbæk, P. (2006). Bullying at work, health outcomes, and physiological stress response. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(1),63-72. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.-06.078 [ Links ]

Heloani, J. R., & Barreto, M. (2010). Aspectos do trabalho relacionados à saúde mental: Assédio moral e violência psicológica. In D. M. R. Glina & L. E. Rocha, Saúde mental no trabalho: Da teoria à prática (pp. 31-48). São Paulo, SP: Roca. [ Links ]

Heloani, R. (2003). Violência invisível. GVExecutivo, 2(3),57-61. [ Links ]

Heloani, R. (2005). Assédio moral: A dignidade violada. Aletheia, 22,101-108. [ Links ]

Heloani, R. (2011). A dança das garrafas: Assédio moral nas organizações. GVExecutivo, 10(1),50-53. [ Links ]

Hirigoyen, M.-F. (2005a). Mal-estar no trabalho: Redefinindo o assédio moral (2. ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Hirigoyen, M.-F. (2005b). Assédio moral: A violência perversa no cotidiano (7. ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. L. (2000). Destructive conflict and bullying at work. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester, Institute of Science and Psychology. [ Links ]

Hoel, H., Sparks, K., & Cooper, C. L. (2001). The cost of violence/stress at work and the benefits of a violence/stress-free working environment. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Organization. [ Links ]

International Labor Organization. (2000). Framework guidelines on workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [ Links ]

Leka, S., & Cox, T. (2008). PRIMA-EF: Guidance on the European framework for psychosocial risk management: A resource for employers and worker representatives protecting workers (WHO Protecting Workers' Health Series No. 9). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [ Links ]

Leymann, H. (1992). Leymann Inventory Psychological Terrorization. Karlskrona, Sweden: Violen. [ Links ]

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2),165-184. [ Links ]

Martiningo, A., Filho, & Siqueira, M. V. S. (2008). Assédio moral e gestão de pessoas: Uma análise do assédio moral nas organizações e o papel da área de gestão de pessoas. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 9(5),11-34. doi:10.1590/S1678-69712008000500002 [ Links ]

Mendes, A. M. (2007). Da psicodinâmica à psicopatologia do trabalho. In A. M. Mendes (Ed.), Psicodinâmica do trabalho: Teoria, método e pesquisas (pp. 29-47). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Monteiro, J. K., & Machado, C. (2010). Violência no trabalho em um hospital público. In A. M. Mendes (Ed.), Violência no trabalho: Perspectivas da psicodinâmica, da ergonomia e da sociologia clínica (pp. 139-154). São Paulo, SP: Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. [ Links ]

Niedl, K. (1996). Mobbing and well-being: Economic and personnel development implications. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2),239-249. doi:10.1080/13594329608414857 [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2004). Sensibilizando sobre el coso psicológico en el trabajo: orientación para los profesionales de la salud, tomadores de decisiones, gerentes, directores de recursos humanos, comunidad jurídica, sindicatos y trabajador. Recuperado en http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/en/pwh4sp.pdf [ Links ]

Ramsay, S., Troth, A., & Branch, S. (2010). Work-place bullying: A group processes framework. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(4),799-816. doi:10.1348/2044-8325.002000 [ Links ]

Rezende, L. O. (2008). Revisitando os elementos estruturais do assédio moral: Um caminho metodológico necessário para a correta compreensão do tema no âmbito jurídico. In L. A. Soboll (Ed.), Violência psicológica e assédio moral: Pesquisas brasileiras (pp. 56-73). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Salin, D. (2008). The prevention of workplace bullying as a question of human resource management: Measures adopted and underlying organizational factors. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(3),221-231. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2008.04.004 [ Links ]

Sheehan, M. (1999). Workplace bullying: Responding with some emotional intelligence. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1-2),57-69. doi:10.1108/01437729910268641 [ Links ]

Soboll, L. A. P. (2006). Violência psicológica e assédio moral no trabalho bancário (Tese de doutorado, Universidade de São Paulo, SP, Brasil). [ Links ]

Soboll, L. A. P. (2008a). Assédio moral no Brasil: A origem da ampliação conceitual e suas repercussões. In L. A. P. Soboll (Ed.), Violência psicológica e assédio moral no trabalho: Pesquisas brasileiras (pp. 23-65). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Soboll, L. A. P. (2008b). Assédio moral/organizacional: Uma análise da organização do trabalho. São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Soboll, L. A. P. (2010). Assédio moral no trabalho. In A. D. Cattani & L. Holzmann (Eds.), Dicionário Crítico Tecnologia e Trabalho (pp. 40-46). Porto Alegre, RS: Editora da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. [ Links ]

Tehrani, N. (2003). Counselling and rehabilitating employees involved with bullying. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace (pp. 270-284). London: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Teixeira, R. F., Munck, L., & Reis, M. C. (2011). Assédio moral: Percepção o gestores de pessoas sobre danos e políticas de enfrentamento. Revisa Gestão Organizacional, 1(4)30-48. [ Links ]

Terrin, K. A. P. (2007). Assédio moral no ambiente de trabalho: Propostas de prevenção. Revista do Direito Público, 2(2),3-24. doi:10.5433/1980511X.2007v2n2p3 [ Links ]

Vartia, M. (1996). The sources of bullying-psychological work environment and organizational climate. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2)203-214. doi:10.1080/13594329608414855 [ Links ]

Vega, G., & Comer, D. R. (2005). Sticks and stones may break your bones, but words can break your spirit: Bullying in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 58,101-109. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-1422-7 [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Vanessa Rissi

Faculdade Meridional - IMED, Departamento de Pós-Graduação Lato Sensu em Psicologia

Rua Senador Pinheiro, 304, Cruzeiro

Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil 99070-220

Phone/Fax: (54) 3045-6100

E-mail: vanessa.rissi@imed.edu.br, janinekm@unisinos.br, willcecconello@yahoo.com.br and moraeseliz@yahoo.com.br

Recebido: 07/10/2014

1ª revisão: 04/03/2015

Aceite final: 31/03/2015

text in

text in