Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Temas em Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.24 no.2 Ribeirão Preto jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.2-19Pt

ARTIGOS

A Case study with the ACT raising safe kids parenting program

Jéssica de Assis SilvaI; Lúcia C. A. WilliamsII

IPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, São Paulo, Brasil

IIDepartamento de Psicologia da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, São Paulo, Brasil

ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to describe a case study of an intervention conducted with a Brazilian mother using the ACT Raising Safe Kids Program - a universal program to prevent violence against children. This study evaluated behavioral aspects of the mother and her six-year old son with pre-post intervention measures, and follow-up. The mother filled the Brazilian instrument Parental Style Inventory (IEP), as well as the ASEBA (CBCL, ASR and ABCL) prior and after the intervention, and at follow-up; in addition to the ACT Program Assessment Questionnaire after the intervention. The husband filled the CBCL and the ABCL in all the study's phases. Results pointed to a change in parental style after intervention (from "High Average" to "Excellent"). Agreement between informants about the child's behavior was found, and disagreement between spouses about mother's behaviors. The fact that the couple decided to separate during the intervention hinders an accurate interpretation of the discrepant results. Studies involving group application of the ACT Program are needed in Brazil.

Keywords: Child abuse, universal prevention, ACT program.

Violence against children is a common problem around the globe and its effects may persist into adulthood, with possible physical, social and mental health consequences to victims (Dubowitz, 2012). There is consensus that children and adolescents, especially those who grow up in homes perceived as violent, should be an important focus in prevention projects (Wolfe & Jaffe, 1999). However, there are few well-evaluated programs focused on primary child care (Dubowitz, 2012).

Behavioral training aimed directly to children without involving caregivers or taking environmental factors into account offers limited success (Knox, Burkhart, & Howe 2011). Knox et al. (2011) argue that it is preferable to adopt an educational approach with parents before maladaptive behavioral problems are rooted in children resulting from ineffective and coercive parenting. Gomide (2003) highlights that frequency and quality of parental practices may favor the development of antisocial behavior (resulting from, for example, physical or psychological abuse, negligence and inconsistent punishment) or prosocial behavior (resulting from positive monitoring and teaching moral values). Thus, the type of established parental relationship seems to be fundamental to a child's development (Carvalho & Gomide, 2005). Intervention focusing on the caregiver's behavior is, therefore, crucial as it may lead to an alternative improvement in the quality of family life, interfering positively, among other things, in the decrease of the parent's individual problems, such as depression (Prada & Williams, 2010).

According to Wolfe and Jaffe (1999), promoting attitudes and behaviors that are incompatible with violence and abuse and encouraging the development of healthy nonviolent relationships would be appropriate prevention goals. Rios and Williams (2008), also defend that the literature is in accordance with positive parenting practices (without the use of physical and psychological violence) associated to children's healthy development, and the adoption of such practices in the parent/child relationship would be an essential step in preventing intergenerational patterns of family violence, assisting in the promotion of competence and adaptive behaviors in children.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2009), has appealed to prevent behavioral problems and child abuse through the development of healthy relationships among children and their caregivers. To that end, parenting programs have been designed to provide support through training skills seeking to ensure children's wellbeing (Mejia, Callan, & Sanders, 2012). Such training is an important orientation tool for parents and caregivers to discipline children aiming at promoting appropriate behaviors, as well as improving their socialization (Bolsoni-Silva & Marturano, 2002; Carvalho & Gomide, 2005).

Parenting programs have proved to be effective preventive strategies in developed countries, however their effectiveness in such context is still limited, as there are obstacles even in determining the prevalence of behavioral and emotional difficulties in these countries (Mejia et al., 2012). In a review of international studies, Prada and Williams (2010) point out that during the 1960s, parenting ntervention programs followed the triadic model, in which the therapist was a mediator between the parents and the child in reducing behavioral problems. During the 70s, the focus of parenting programs involved specific behavioral problems, such as a child's oppositional behavior. In the 80s, studies began to consider parental characteristics as contributing factors to the development of certain behaviors in children, as well as moderating the results of the interventions. However, it was not until the 90s that answers to the concern with maintenance and generalization of research results appeared, and the focal point of studies came to be prevention and its pertaining topics: risk and protective factors, support systems, the family's living environment and its relationship with the child, the school and the community.

Rios and Williams (2008) also reviewed Brazilian and international intervention studies with families stating that, in spite of the fact that there are several intervention studies with parents within the Brazilian scenario, they are still scarce when compared to more developed countries. A social skills group-training program involving four couples was developed by Bolsoni-Silva, Del Prette, and Del Prette (2000). Through the use of instructional techniques, behavioral rehearsal, modeling and homework assignments, participants showed an increase in interpersonal skills after the training, such as expression of affection and contingent attention, use of positive reinforcement, positive problem solving techniques and less use of punishment. Nevertheless, non-compliance and aggression problems persisted in the children.

Bolsoni-Silva (2007) described another group intervention involving 14 sessions aiming at increasing positive practices for parents and reducing their negative practices, thus expanding children's social skills repertoire. A reduction in externalizing problems presented by children was observed as mothers increased the expression of feelings, limit setting and establishing of consequences for behaviors they did not appreciate (Bolsoni-Silva, 2007). In a similar procedure, Bolsoni-Silva and Marturano (2010) evaluated three groups consisting of four caregivers each, with pre and post-intervention control measures. Following two months of intervention in which measures were provided by the Inventário de Habilidades Sociais (Social Skills Inventory), a functional assessment of interactions involving the parent and child, and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), found a decrease in negative parenting practices, as well as reduction in child behavioral problems following the intervention. Nevertheless, there was no significant increase in positive practices by parents towards the child.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to describe all recent Brazilian studies or programs of parental intervention, it is also worth mentioning Project Parceria (Partnership), a secondary and tertiary prevention of violence program designed to teach positive skills to mothers victims of intimate partner violence to prevent behavioral problems in children (Pereira, D'Affonseca, & Williams, 2013; Williams, Santini, & D'Affonseca, 2014). Additionally, Santini, D'Affonseca, Ormeño, and Williams (2012) describe a case study using the Parceria Project with a 43-year-old mother who had been previously incarcerated. The authors found improvement in the mother's performance in all instruments used (Child Abuse Potential Inventory - CAP, the Inventário de Estilos Parentais - IEP - Parenting Styles Inventory - and the Beck Depression Inventory - BDI) in pre and post-test and follow-up measures. Based on the participant's report, improvements were noted in social skills, social problem solving and self-esteem after 20 individual weekly meetings.

Silvares and Banaco (2000) defend the relevance of case studies as they may bring research and practice closer. Nevertheless, there are few case studies in the Brazilian literature describing the parental training trajectory, as well as its procedures and results so that this research modality may bridge the gap between theory and practice. Although there is no consensus on how to proceed regarding case study reports, this is one of the methodologies available to clinicians and researchers to generate knowledge in the realm of Psychology (Silvares & Banaco, 2000). Indeed, Peres and Santos (2005) reported an increasing trend in the regular use of case studies in the humanities and social sciences. In spite of its exploratory nature and the difficulty involved in generalizing data, this methodology may assist in the development of hypotheses for future research (Del Prette, Silvares, & Meyer, 2005).

A case study of child aggression in a clinical context in Brazil involved the assessment of parent training in terms of parental behavior changes and its effects on the aggressive behavior of a 9 year old (Emidio, Ribeiro, & De-Farias, 2009). Parents were asked to record the frequency of the aggressive behavior, as well as to identify the previous history and consequences of such behavior. After identifying contingencies that aided in the acquisition and maintenance of the aggressive behavior, they were instructed to reinforce appropriate behaviors, behave consistently with rules imposed on the child, apart from being taught to replace threats with positive practices. Among the achievements, a decrease in frequency of verbal and physical aggressive behavior was observed, as well as an increase in social skills and improvement of family interactions.

Kaiser (2013) has also conducted a case study involving training with mothers of two families who were non-compliant with the criteria established by the Programa Bolsa Familia (Family Cash Allowance Transfer Program). The children had poor school attendance, and in addition much conflict was seen in the family (e.g. inconsistent punishment and intrusive monitoring by the mother, alcohol abuse by an adolescent daughter). The training consisted of teaching dialogue as negotiation and conflict resolution techniques, strengthening of bonds, use of positive reinforcement and efforts to comply with the rules concerning the behavior of the children. Data from the IEP, answered by children and their mothers reflected positive results in both cases.

The ACT Program

Unlike the aforementioned Project Parceria, ACT is a universal child abuse prevention parenting program whose name stands for Adults and Children Together - Raising Safe Kids Program (ACT-RSK). The program was developed by the American Psychological Association - APA (Silva, 2011), and has been proven to be effective in preventing nonadaptive interactions (i.e., the use of violence) among parents and children, reducing and preventing behavior problems and contributing to the decline of externalizing behaviors in children (Knox, Burkhart, & Hunter, 2010; Knox et al., 2011). The program (henceforth denominated as ACT) had the initial support of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and was based on empirical findings The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program has a version in Portuguese: Programa ACT para Educar Crianças em Ambientes Seguros (Silva, 2011). In addition to social-cognitive interventions (didactic instruction, modeling, role-playing), the program includes group parent training with information on child development, risk factors for healthy development, communication and other social skills training, as well as non-violent conflict resolution skills (Knox et al., 2011).

ACT trains professionals and parents to define appropriate child behavior according to each developmental stage, emphasizing the importance of parents playing a positive role to the child, by monitoring and guiding their behavior without the use of violence, and adopting pro-social practices instead. The program also highlights the importance of involving parents in schools and communities to prevent the exposure of violence by children (Knox et al., 2011).

Although there is ongoing research on ACT in several Universities, in Brazil, there are yet no studies published on its effectiveness in this country (Silva & Williams, 2015). The case study to be described resulted from a failed initial attempt to apply the ACT in a group format (such as the model proposed). Obstacles found concerning adherence to the group derived from various factors involved in challenges of working with mothers living in extreme poverty, with low educational level, and residing in vulnerable neighborhoods. Initially, 13 mothers demonstrated an interest in participating of the Program, six signed Informed Consent, but only two attended the first training session. Finally, only one mother, who had a contrasting profile from the others (she had a high educational and income levels), took part of the entire intervention. Thus, the present study is aimed at reporting an individualized adaptation of the ACT procedure, analyzing data in which the mother assessed herself and her only child, as well as reports from a third-party (mom's husband and father of the child).

Method

Participants

This case study involved one participant, whom we will call Maria, a 36-year-old mother with a Bachelor's degree in a health-related area, taking a doing a Master's degree at the time. The participant was married and had only one child, a six year-old boy. She had a monthly income above six Brazilian minimum wages, placing her at an upper socioeconomic level according to "Brazil Criteria" (Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa [Brazilian Association of Research Enterprises], 2013). Her husband was 43, he also had a Bachelor's degree in a health-related area and had attended Graduate School.

Location

The study was conducted in a Non-Government Organization (NGO) located in a high socially vulnerable neighborhood in a midsize city situated in the interior of São Paulo State. The participant did not reside near the NGO and was informed about the program through a health clinic in the city (the intervention was widely publicized by the written press and radio).

Instruments

ACT Program Assessment Questionnaire, used to measure the participant satisfaction with the Program. There were four questions in total: the first one with sub-items to be filled marking "strongly disagree", "disagree", "do not know", "agree", "totally agree" in regards to statements regarding the program's facilitators, its applicability to daily life and suggestions to improve the intervention; the second question on what the program may have helped the participant to learn; the third one on what had the participant liked about ACT; and the fourth question about what the participant would alter in the program.

Inventário de Estilos Parentais (IEP [Parental Styles Inventory]; Gomide, 2006). Assesses the parental styles of caregivers, classifying them into the following groups: Excellent parental style, when there are positive disciplinary practices without the occurrence of negative (or violent) practices; High Average parental style, in which it is only recommended to the parents to read Parenting Manuals for improvement; Bellow-Average parental style when it is recommended that parents/caregivers participate in parent training groups; and At-Risk parental style, for which therapeutic intervention is recommended. Seven sub-categories are evaluated with six items each: positive monitoring, moral behavior, inconsistent punishment, negligence, permissive discipline, negative monitoring and physical abuse, with total scores in each category ranging from 0-12.

Adult Self-Report (ASR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), verifies various aspects of adaptive adult functioning from the participant's point of view, providing relevant data on the characteristics of the population seen, as well as the types of problem behaviors that appear more frequently. This study will analyze exclusively the Aggressive Behavior Scale and the Total Scale of Behavior Problems. The problems are classified with the normal (non-clinical), borderline or clinical range, and this scale also identifies psychopathologies based on manuals such as the DSM-IV (Achenbach, 2001). The ASR as well as the ABCL (instruments described below) are in process of cross-validation to Brazil by Silvares (2013), who has authorized their use in the present study. Studies involving the CBCL validation to Brazil (for ages 6-18) are already found in the literature (Bordin et al., 2013; Rocha et al., 2012).

Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL, ages 1859), is answered by family members, friends or persons close to the adult and aims to assess the same items as the ASR to allow for comparisons among respondents (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL, ages 6-18) includes 118 items with the following subscales: Anxiety/depression; Withdrawal/depression, Somatic complaints, Social problems, Attention problems, Thought-Problems, Rule-breaking behavior and Aggressive behavior. These subscales are divided into an Internalizing Scale (IS), and an Externalizing Scale (ES). It also includes six scales in accordance to the diagnostic criteria established by the DSM-IV: Depressive Problems, Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems, Oppositional Defiant Problems, and Conduct Problems.

A Field Journal in which the facilitator recorded at each session the use of strategies employed by the participant during the intervention, as well as her verbalizations about the Program's structure and acceptance to qualitatively monitor participant's changes.

Procedure

The University's Institutional Review Board approved this study, and participants signed the Informed Consent Form. To implement the ACT Program in Brazil, a partnership between LAPREV (The Laboratory for Violence Analysis & Prevention), and LAPREDES (The Laboratory for the Prevention of Developmental & Behavior Problems in Children) with APA, for the purpose of developing validation studies of ACT to the Brazilian reality. As a result, an ACT training workshop was provided by the Director of APA's Violence Prevention Division to researchers from both laboratories, along with translation of the ACT materials into Portuguese.

The ACT Program involves eight weekly group session with an average of two hours duration each, covering the following topics: understanding children's behavior; young children's exposure to violence; understanding and controlling parent's anger and angry children; solving conflicts in a positive way; discipline for positive behaviors; parenting styles, influence of electronic media on children's behavior and incorporation of the Program in the community. These topics encompass the program's four prevention strategies in line with current knowledge on child development: anger management, social problem solving, positive discipline and children's exposure to electronic media (Silva & Randall, 2005).

The ACT program (Silva, 2011) contains several manuals for its application: (a) a Manual for Parents and Caregivers, where information sheets referring to matters covered in each session can be found; (b) The Facilitator's Guide, which describes each of the program's sessions, explaining step-by-step the activities for implementation in the group; (c) The Motivational Interview Guide (MI) in which motivation and level of participants' readiness to change is explored (this material is covered before the program's first session and at the end of sessions 5 and 8); and (d) An Evaluation Guide.

Considering the difficulties mentioned previously in doing a group intervention, adaptations were made to the ACT protocol to suit an individual format from the fourth session onwards, when the second participant withdrew (as a result of losing custody of her child). Group activities such as role-playing and making collages were carried out with the help of facilitators asssuming the role of other participants. Due to the individual format of the intervention (without the imput of other participants), the interaction of Maria and her child became examples for the implementation of strategies and concepts to be learned while working with the Parent Handbook's factsheet.

The procedure consisted of four phases: (a) pre-intervention (two sessions of approximately two hours) in which Maria and her husband answered individually the IEP, ASR, ABCL and CBCL; (b) intervention, consisting of the eight evening sessions of the ACT program, taking place once a week for two hours with a 15 minute interval; (c) post-intervention (two sessions of two hours), in which Maria and her husband answered all the instruments again, and her opinion regarding the ACT Program was assessed through the Program's Evaluation Questionnaire; (d) follow-up (two sessions of two hours) after a three month interval after the intervention when all the instruments were re-applied with the two participants. During the first phase, the instruments were filled out in a group format (with other mothers who signed the Informed Consent Form), and in the following phases, the instruments were filled out individually.

Two psychologists who were completing their Master's at a Psychology Graduate Program, including the first author of the present study, led the ACT program. Throughout the intervention, supervision of the child was offered as well as a snack. In addition, small gifts were provided as incentives to the mother (such as sweets, children books and toys, etc.).

Data Analysis

Total scores obtained by the mother at each study phase were considered for the IEP, taking into consideration the score category for each phase of the study. For the ASEBA (Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment) or Achenbach instruments, the aggressive behavior scales of mother and child were compared as well as total behavior problem scales. Data indicating behavior changes from pre to post-test and follow-up, or scores showing disagreement among informants within a given period was taken into consideration for data analysis. The ASEBA data was analyzed using the Assessment Data Manager (ADM), software specially developed by Achenbach for this purpose (2006).

Results

In the pre-intervention phase, Maria disclosed to that she was having problems in her marital relationship, signaling the possibility of a divorce.

Parental Style Inventory

Analysis of the scores obtained by Maria in her Parental Style Inventory (IEP) indicated that during the pre-test her style was classified as High Average (total score = 9, 75th percentile), whereas in the post-test, Maria was classified as having an "Excellent parenting style" (total score = 12. 8th percentile), which is indicative of a strong presence of Positive parenting practices and absence of Negative ones. This parental style was maintained at follow-up (total score = 14, 90-96th percentile) three months after her participation in the group.

ASEBA

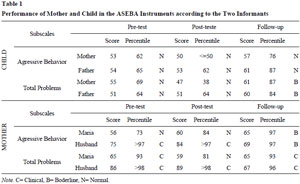

Table 1 below displays the results of the mother and child in the ASEBA instruments. There was agreement in the father's and mother's assessment of the child in the CBCL. The boy presented scores in the normal range in pre-test for aggressive behavior, maintaining this level throughout the study (post-test and follow-up). As for the total score for problems, these were also in the normal range in the post-test, with a decrease to the borderline range in the follow-up phase.

According to Table 1, a discrepancy, in general, was observed between Maria's reports in her ASR self-assessment and the assessment made by her husband in the ABCL in terms of adaptive functioning and behavioral problems. According to Maria, improvements were noted in the total score of problems, changing the classification from the clinical range (pre-test) to normal (post-test). In contrast, according to her husband, Maria remained in the clinical range along all stages of the evaluation, not showing improvement. As for the follow-up measures, Maria appraised herself in the Borderline range for aggressive behavior, in agreement with her husband who also classified her within this range.

According to Maria's self-assessment, she maintained a level of normal adaptive functioning, indicating lack of aggressiveness (normal range), in pre- and post-test, which was not maintained during the follow-up when there was a drop in performance (Borderline). According to the evaluation of Maria's husband, she maintained the clinical level scores throughout pre and post-tests, with an improvement three months after the intervention at follow-up. To him, the total scores of Maria's externalizing and internalizing problems remained at the clinical level at all stages of the evaluation, while Maria saw self-improvement after the intervention, although such changes did not stabilize in the follow-up phase.

ACT Program Assessment Questionnaire

According to the ACT Assessment Questionnaire, Maria already had knowledge on the Program's topics before starting the intervention. She presented above average scores at all scales in the pre-intervention phase, post-intervention and follow-up in regards to the topics targeted in the Program, without relevant changes among the different phases. In the Program's Assessment Questionnaire, the mother reported that the facilitators were well-versed on the subject, in addition to being courteous and efficient. She also stressed that she had enjoyed the Program, as it had provided her with good alternatives in dealing with her child, stating that she would incorporate the techniques learned. In spite of considering the program lengthy, she would recommend it to others, and reported that the meetings had helped her reflect on the issues addressed, and remind them at each session.

Field Journal

As previously mentioned, while answering the ASEBA instruments in the pre-test, Maria disclosed that she was having difficulties in her marital relationship. As reasons for her interest in taking part of the Program, she mentioned the fact that others claimed she did not set limits to her son, as well as her desire to "yell less" at her child. In the second session of the intervention, the mother had difficulty describing the types of violence that could occur (sexual, physical, psychological abuse and neglect), struggling to define them, especially in regards to negligence. At the same meeting, Maria expressed that she was nervous during an activity that required ripping a paper doll at the mention of every risk factor a child may experience, expressing that she understood that violence leaves marks in children.

The mother stated that the conflict resolution models outlined by the Program helped her calm down before making decisions in regards to how to discipline her child. Maria reported that she had printed copies of some of the Program's material to display at home to help her remember to not act impulsively. During the session on electronic media, Maria said she "had never stopped to think" until then about the examples of "heroes" that we expose our children to in video games and television, and that we should seek true examples of heroes in our own community. "Every situation is an opportunity to teach, isn't it? I do think this thing about the heroes is really neat... ", she said.

Regarding parenting styles, Maria recognized during the discussion that much of what she was doing to educate her son was, in a way, a result of the way she was brought up, and admitted that she previously was unaware of this connection and the Program had helped her understand certain behaviors she presented. By the sixth session, Maria reported that her son was talking to her more frequently, sharing facts that were happening at school (in the first session, Maria had identified as a problem the fact that her son did not talk to her much). The participant also reported that her relationship with the child had grown closer, and said that she was pleased with these results.

In the post-test, the mother informed that she had opted to initiate the separation proceedings. She also said she had managed to maintain a good relationship with her son, consulting the material handed during the intervention. In the follow-up, Maria reported, that her husband had moved out of the house, claiming to be happy with the decision. She also stated that, with the improvements in communication with her child, she was able to introduce the topic of separation with him in attempt to minimize its effects on his development.

Discussion

Maria took part in all of the program's sessions, never missing a single session. Her attendance was surprising as the Program required her to weekly take a long route from home to a distant neighborhood in the city's outskirts. This adhesion may have been favored by: (a) her high income and education (parents with these characteristics display higher engagement in training programs (Webster-Stratton, 1998); (b) her motivation in dealing successfully with a family crisis due to an eminent separation, and (c) the benefits that she possibly gained from taking part of the ACT Program.

In regards to such benefits, the Parental Style Inventory data showed an increase in the positive practices performed by the mother, topic dealt in detail with the participant during the positive discipline module provided by the Program's protocol. The stability of the data in follow-up, obtained with a valid instrument which compares measures collected before and after the intervention, suggests that the intervention may have led to the perceived changes, in spite of the simple case study method (Kazdin, 2003). These results are also reinforced by the fact that qualitative data from the field journal indicated that Maria found the Program beneficial and did not miss sessions.

Nevertheless, the same benefits in positive practice and improvement of parental style from Above Average to Excellent was not observed in the data collected by Maria's husband. This discrepancy may have been maximized by the fact that the couple was going through a divorce, which may have led the husband to assess his wife in more negative terms. Thus, data collection with the help of observational data could confirm this hypothesis and could be employed in future studies, as well as the use of more complex methodological research designs.

Regarding the child's performance, Maria's son had already presented adaptive behavior (situated in a non-clinical range) on the scales evaluated by the CBCL according to both parents, and thus the ceiling effect made impossible for improvement. Data collection with additional informants, such as teachers could confirm this result, providing external validity with data from non-family members family.

The fact that Maria was going through a divorce process in itself justified the need for a Parenting Program intervention. Indeed, the literature shows that parental stress is a major influential variable in family performance in intervention programs (Farrelly & Mclennon, 2010; Mytton, Ingram, Manns, & Thomas, 2014). Williams and Aiello (2004) cite McKenry and Price's book (1994), reviewing major forms of stress families may have to cope with, reminding us that divorce is considered one of the worst stressors. The literature also points out that it is less likely for adequate parenting skills to be maintained in an environment with marital crises, and that in this context of separation the likelihood of parents and children exhibiting behavioral problems is increased (Amato, 2000; Dadds, Schwartz, & Sanders, 1987; Kelly & Emery, 2003; Raposo et al., 2011). In this sense, the quality of the marital relationship of the parents who are participants of training programs may influence their performance (Moran, Ghate, & Van der Merwe, 2004), as in the example of the disparate results in ASEBA instruments.

This case study illustrates that, as intended in a universal program for violence prevention, ACT was helpful to Maria (according to her reports and the data collected), despite the fact that she was a mother with high education and income. Thus, ACT seemed to have helped her improve her parenting style, giving knowledge and new information on positive parenting practices. Additionally, despite not being the focus of the program, the Program seemed to have helped Maria deal with issues associated with child rearing during the separation crisis, reassuring and helping her to solve problems in non-violent ways, the latter one of the goals of the Program.

The authors would like to state that in spite of the fact that Maria's high educational level possibly maximizing her participation, this does not mean that the ACT Program is effective only with such parents. ACT has been used successfully with a wide population of parents in several countries according to the review of its implementation by Silva and Williams (2015), and a similar conclusion was found by Altafim & Linhares, 2016.

In spite of the difficulties with result generalizations, case studies are important to developing hypotheses about clinical problems and obtain knowledge on innovative treatments (Kazdin, 2003). Additionally, such studies may facilitate opening ground for future investigations with distinct research designs (Del Prette et al., 2005). Future interventions involving validation of the ACT program to Brazil should have group research designs and randomized controlled trials (RTC), while maintaining the use of multiple informants for data collection, in order to substantiate results. In addition, we must strive to look for relevant instruments for data collection, and appropriate assessment of its efficacy, as the ACT's assessment instruments result only in qualitative data.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (2001). Manual for the Data Manager Program (ADM): CBCL, YRS, TRE, YARS, YABCL, CBCL/2-3, CBCL/½-5 & C-TRF. Burlington, VT: Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. [ Links ]

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [ Links ]

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [ Links ]

Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. (2006). Manual for the Assessment Data Manager Program (ADM). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. [ Links ]

Altafim, E.R.P. & Linhares, M.B.M. (2016). Universal violence and child maltreament prevention programs for parents: A systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 25(1),27-38. [ Links ]

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62,1269-1280. doi:10.1111/j.17413737.2000.01269.x [ Links ]

Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. (2013). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil. Recuperado em http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2007). Intervenção em grupo para pais: Descrição de procedimento. Temas em Psicologia, 15(2),217-235. [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2000). Relacionamento pais-filhos. Um Programa de desenvolvimento interpessoal em grupo. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 3(3),203-215. [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., & Marturano, E. M. (2002). Práticas educativas e problemas de comportamento: Uma análise à luz das habilidades sociais. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 7(2),227-235. doi:10.1590/S1413-294X2002000200004 [ Links ]

Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., & Marturano, E. M. (2010). Evaluation of group intervention for mothers/caretakers of kindergarten children with externalizing behavioral problems. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 44(3),415-421. [ Links ]

Bordin, I. A., Rocha, M. M., Paula, C. S., Teixeira, M. C. T. V., Achenbach, T. M., Rescorla, L. A., & Silvares, E. F. M. (2013). Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) e Teacher's Report Form (TRF): Uma visão geral sobre o desenvolvimento das versões originais e brasileiras. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29(1),13-28. doi:10.1590/S0102311X2013000100004 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. C. N., & Gomide, P. I. C. (2005). Práticas educativas parentais em famílias de adolescentes em conflito com a lei. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 22(3),263-275. doi:10.1590/S0103-166X2005000300005. [ Links ]

Dadds, M. R., Schwartz, S., & Sanders, M. R. (1987). Marital discord and treatment outcome in behavioral treatment of child conduct disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55,396-403. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.3.396 [ Links ]

Del Prette, G., Silvares, E. F. M., & Meyer, S. B. (2005). Validade interna em 20 estudos de caso comportamentais brasileiros sobre terapia infantil. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 7(1),93-105. [ Links ]

Dubowitz, H. (2012). The safe environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model: Child healthcare professionals helping prevent child maltreatment. In H. Dubowitz (Ed.), World perspectives on child abuse (10th ed., pp. 89-92). Aurora, CO: International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. [ Links ]

Emídio, L. A. S., Ribeiro, M. R., & De-Farias, A. K. C. R. (2009). Terapia infantil e treino de pais em um caso de agressividade. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 11(2),366-385. [ Links ]

Farrelly, A. C., & Mclennan, J. D. (2010). Participation in a Parent Education Programme in the Dominican Republic: Utilization and barriers. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 56(3),149-158. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmp071 [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C. (2003). Estilos parentais e comportamento anti-social. In Z. Del Prette & A. Del Prette (Eds.), Habilidades sociais, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem: Questões conceituais, avaliação e intervenção (pp. 21-60). Campinas, SP: Alínea. [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C. (2006). Inventário de Estilos Parentais (IEP): Modelo teórico, manual de aplicação, apuração e interpretação. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Kaiser, F. A. (2013). Treino de habilidades parentais: Estudo de caso com famílias em descumprimento de condicionalidades do Programa Bolsa Família (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, PR, Brasil). [ Links ]

Kazdin, A. E. (2003). Drawing valid inferences from case studies. In A. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (pp. 655-669). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children's adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations, 52,352-362. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x [ Links ]

Knox, M. S., Burkhart, K., & Hunter, K. E. (2010). ACT Against Violence Parents Raising Safe Kids Program: Effects on maltreatment-related parenting behaviors and beliefs. Journal of Family Issues, 32,55-74. doi:10.1177/0192513X10370112 [ Links ]

Knox, M., Burkhart, K., & Howe, T. (2011). Effects of the ACT Raising Safe Kids Parenting Program on children's externalizing problems. Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies - Family Relations, 60,491-503. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00662.x [ Links ]

Mejia, A., Calam, R., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). A review of parenting programs in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges for preventing emotional and behavioral difficulties in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15,163-175. doi:10.1007/s10567-0120116-9 [ Links ]

Moran, O., Ghate, D., & Van der Merwe, A. (2004). What works in parenting support: A review of the international evidence (Research Report No. 574). London: Department for Education and Skills. [ Links ]

Mytton, J., Ingram, J., Manns, S., & Thomas, J. (2014). Facilitators and barriers to engagement in parenting programs: A qualitative systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 4(2),127-137. doi:10.1177/1090198113485755 [ Links ]

Pereira, P. C., D'Affonseca, S. M., & Williams, L. C. A. (2013). A feasibility pilot intervention program to teach parenting skills to mothers of poly-victimized children. Journal of Family Violence, 28,5-15. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9490-9 [ Links ]

Peres, R. S., & Santos, M. A. (2005). Considerações gerais e orientações práticas acerca do emprego de estudos de caso na pesquisa científica em psicologia. Interações, 10(20),109-126. [ Links ]

Prada, C. G., & Williams, L. C. A. (2010). Intervenção em práticas educativas para pais e cuidadores em abrigo: Uma revisão. In L. C. A. Williams, J. M. D. Maia, & K. S. A. Rios (Eds.), Aspectos psicológicos da violência: Pesquisa e intervenção cognitivo-comportamental (pp. 271 -290). Santo André, SP: ESETec. [ Links ]

Raposo, H. S., Figueiredo, B. F. C., Lamela, D. J. P. V., Nunes-Costa, R. A., Castro, M. C., & Prego, J. (2011). Ajustamento da criança à separação ou divórcio dos pais. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica, 38(1),29-33. doi:10.1590/S010160832011000100007 [ Links ]

Rios, K. S. A., & Williams, L. C. A. (2008). Intervenção com famílias como estratégia de prevenção de problemas de comportamento em crianças: Uma revisão. Psicologia em Estudo, 13(4),799-806. doi:10.1590/S1413-73722008000400018 [ Links ]

Rocha, M. M., Rescorla, L. A., Emerich, D. R., Silvares, E. F. M., Borsa, J. C., Araújo, L. G. S., ...Assis, S. G. (2012). Behavioural/emotional problems in Brazilian children: Findings from parent's reports on the Child Behavior Checklist. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 22(4),1-10. doi:10.1017/S2045796012000637 [ Links ]

Santini, P. M., D'Affonseca, S. M., Ormeño, G. R., & Williams, L. C. A. (2012). Violência doméstica e encarceramento: Um estudo de caso. Multiciência (ASSER), 11,212-222. [ Links ]

Silva, J. (2011). ACT Raising Safe Kids Program. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Silva, J. A., & Williams, L. C. A. (2015). O programa ACT para educar crianças em ambientes seguros: Da elaboração à avaliação. In S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-França, K. B. Santos, & L. Polejack (Eds.), Prevenção e promoção em Saúde Mental: Fundamentos, planejamento e estratégias de intervenção (pp. 489-300). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopsys. [ Links ]

Silva, J. M., & Randall, A. (2005). Giving Psychology away: Educating adults to ACT against early childhood violence. Journal of Early Childhood & Infant Psychology, 1,37-43. [ Links ]

Silvares, E. F. M. (2013). Estudo de validação multicultural do "Inventário de Autoavaliação para Adultos" (ASR) e do "Inventário de avaliação de Adultos de 18 a 59 anos" (ABCL): Dados brasileiros (Relatório apresentado à Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo). Dados brutos não publicados. [ Links ]

Silvares, E. F. M., & Banaco, R. A. (2000). O estudo de caso clínico comportamental. In E. F. M. Silvares (Ed.), Estudos de caso em Psicologia Clínica Comportamental Infantil (7. ed., Vol. 1, pp. 31-48). Campinas, SP: Papirus. [ Links ]

Webster-Stratton, C. (1998). Parent training with low-income families. In J. Lutzker (Ed.). Handbook of child abuse research and treatment (pp.183-210). New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Williams, L. C. A., & Aiello, A. L. R. (2004). Emponderamento de famílias: O que vem a ser e como medir. In E. G. Mendes, M. A. Almeida, & L. C. A. Williams (Eds.), Temas em Educação Especial: Avanços recentes (pp.197-202). São Carlos, SP: EDUFSCar. [ Links ]

Williams, L. C. A., Santini, P. M., & D'Affonseca, S. M. (2014). The Parceria Project: A Brazilian parenting program to mothers with a history of intimate partner violence. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(3),101-107. doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140403.04 [ Links ]

Wolfe, D. A., & Jaffe, P. G. (1999). Emerging strategies in the prevention of domestic violence. In The future of children: Domestic violence and children (pp. 133-144). Los Altos, CA: The David and Lucile Packard Foundation. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2009). Preventing violence through the development of safe, stable and nurturing relationships between children and their parents and caregivers (Series of Briefings on Violence Prevention: The Evidence). Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [ Links ]

Recebido: 03/10/2014 Mailing adress:

Mailing adress:

Jéssica de Assis Silva

Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Departamento de Psicologia, Laboratório de Análise e Prevenção

da Violência

Rodovia Washington Luís, km235

São Carlos, SP, Brazil 13565-905

E-mail: jehpsi87@gmail.com and williams@ufscar.br

1ª revisão: 15/06/2015

Aceite final: 25/06/2015

The authors acknowledge "Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo" (FAPESP/grant no. 2013/10417-6) for the financial support. This study is part of a Project submitted to the Institutional Review Board from the Universidade Federal de São Carlos (document no. 277.394).

texto em

texto em