Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.24 no.4 Ribeirão Preto dic. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.4-02Pt

ARTIGOS

Vera case: psychotherapist interventions and therapeutic alliance

Evandro Morais PeixotoI; Giovanna Corte HondaII; Maria Leonor Espinosa EnéasIII; Glaucia Mitsuko Ataka da RochaIV; Sonia Maria da SilvaV; Daniela WiethaeuperVI

IPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia como Profissão e Ciência da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil

IIUniversidade Nove de Julho, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

IIICentro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

IVEstudos Avançados - Centro Universitário São Camilo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Faculdade de Medicina de Marília, Marília, SP, Brazil Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

VUniversidade Guarulhos, Guarulhos, SP, Brazil

VIDépartement de Psychologie, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, Québec, Canadá

ABSTRACT

Variables relating to the therapist, the patient and the quality of their relationship are associated with factors that contribute to the success of the psychotherapy. The main goal of this study was to evaluate a brief psychodynamic psychotherapy process and to establish a relation between two of these aspects: the therapist's verbal interventions and the therapeutic alliance. A single-subject case study was used as well as clinical instruments to evaluate the proposed variables: Therapeutic Interventions Classification (TI) and the Working Alliance Inventory Short - Observer version (WAI-S-O). The results pointed to the therapist's intervention strategy, predominantly expressive, and an increase in the average of the therapeutic alliance from the initial phase through the other phases. Moreover, the interventions were also modulated by the inherent characteristics of the different phases of the therapeutic process, in particular the final stage, where the central conflict of the patient relationship, the fear of being abandoned, could be reedited and elaborated. Limitations of the study are indicated.

Keywords: Psychotherapy change (psychology), psychotherapeutic processes, single case study.

Studies carried out over the course of the last four decades show that psychotherapy, regardless of theoretical orientation or mode of treatment, helps to promote change in patients (Prochaska, 1995; Yoshida, 2012). The existence of factors which are common to all psychotherapeutic approaches may explain these findings, inasmuch as the factors that contribute to successful psychotherapy are linked to facets of the psychotherapist, patient and the quality of the relationship between them (Lhullier, Nunes, & Horta, 2006; Meyer, 2006; Santibáñez Fernandez et al., 2008). Thus, the main aim of the present study is to evaluate a brief psychodynamic psychotherapeutic process, relating the variables of the therapist and the relationship between the two.

As far as the facets of the psychotherapist are concerned, Fiorini (2004) and Gabbard (2006) assert that it is possible that their involvement in the process is measured through their verbal interventions. Intervention strategies, identified by means of the types of intervention that psychotherapists conduct throughout the sessions, may have a direct influence on the process outcome (Fiorini, 2004; Gabbard, 2006; Khater, Peixoto, Honda, Enéas, & Yoshida, 2014). According to Gabbard (2006) and Luborsky (1984), interventions in the practice of psychodynamic psychotherapy may be classified as a Supportive-Expressive continuum. Techniques that are "supportive" in nature aim to maintain the patient's level of functioning. These are techniques that demonstrate how much the psychotherapist understands the patient's situation, which increases the probability of being able to establish a therapeutic alliance between them. On the other hand, techniques of an "expressive" nature aim to facilitate communication and comprehension by the patient of his/her unconscious problems and conflicts (Luborsky, 1984). Where psychodynamic psychotherapy is involved, it is expected that interventions would not be limited to one extreme or the other, but rather that there is an optimal point of equilibrium somewhere in the middle that may benefit the quality of the therapeutic alliance (Despland, Roten, Despars, Stigler, & Perry, 2001).

The psychotherapist-patient relationship may be expressed by the variable known as the therapeutic alliance, also known as the working alliance, helping alliance or therapeutic relationship or bond. For Martin, Garske and Davis (2000), this conceptual variation stems from the different theoretical constructs that exist in psychology. All approaches, however, stress the importance of the therapeutic alliance in the psychotherapeutic process and it is generally accepted that once it has been established, it can generate results favorable to the process (Falkenström, Granström, & Homqvist, 2014; Luborsky, 2000; Yoshida & Enéas, 2013).

Specifically with regard to the influence exerted by the quality of the therapist's or patient's alliance on the process outcome, Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, and Wampold (2012) performed a meta-analysis, concluding that the variability in the alliance on the part of the psychotherapist is seen to be more important in terms of the outcome of the therapy when compared to that of the patient. They therefore recommend that the graduate programs of future therapists focus on the development and strengthening of the therapist's ability to establish a therapeutic alliance with the patient. In this regard, Safran et al. (2014) investigated the impact of training that focuses on this alliance and amassed evidence that this type of training has a positive impact on the interpersonal process during sessions, as well as on the ability of the therapist to reflect on the psychotherapeutic relationship, incorporating his/her own experience into this reflection.

Despite the existence of many studies on the therapeutic alliance, Wiseman and Tishby (2014) highlighted the challenges still to be faced, such as that of understanding the function of the relationship between therapist and patient in the change process, its development over the course of the various phases of the process and the type of influence that each has on the quality of this relationship.

Given the understanding of the importance of the psychotherapist-patient alliance within the psychotherapeutic process, researchers began to join forces to build tools capable of measuring this construct and to look for empirical evidence of narrower relationships with the results of the psychotherapy and the characteristics of psychotherapists and patients (Muran & Barber, 2010). One of the tools most commonly used to evaluate this is the Working Alliance Inventory -WAI (Bernecker, Levy, & Ellison, 2014; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). The WAI is a tool that consists of versions for patients, therapists and observers (Busseri & Tyler, 2003). According to Prado and Meyer (2004), this tool stands out because it is one that appears most often in the specialized literature, due to its proven accuracy and validity, to the possibility of it being used throughout the psychotherapeutic process, since it does not focus on the sessions per se but rather the objective, the task and the patient-therapist relationship.

One of the main motives for carrying out this study was that, although a number of other studies have stressed the interaction between therapist variables, such as psychotherapeutic interventions, and patient variables, such as the relationship pattern, for example (Slonim, Shefler, Gvirsman, & Tishby, 2011; Tishby & Vered, 2011; Yoshida et al., 2009), variables dealing with the interaction between therapist and patient still require further study. So we sought to explore possible relationships between the intervention strategies adopted by the psychotherapist and the quality of the therapeutic alliance established between patient and psychotherapist.

Method

The method employed was to use an actual, single-subject case study, enabling an understanding, during the session, of the characteristics of interactive and behavioral patterns between patient and psychotherapist, through an intensive, systematic examination of the case (Eells, 2007; Meyer, 2006; Yoshida et al., 2009).

Clinical Case

Patient: a 23 year-old woman and university student referred for psychotherapy by one of her course lecturers.

Complaints: She presented with an eating disorder, specifically bulimia. Despite demonstrating a desire to eliminate these symptoms, she was very disappointed that these attempts had not met with success.

Psychotherapy: 11 fifty-minute, individual weekly sessions conducted in the graduate school clinic.

Background: born into a middle-class family, she experienced financial difficulties after her father fell ill and became unemployed, which troubled her greatly. She had no memories of her mother who had died when she was a small child, recalling only a photograph that she cherished dearly. After her mother passed away, her father sent her to be looked after by her grandmother. The father began another relationship soon after his wife died and the patient went back to live with her father after he remarried. The patient had great difficulty in relating to her stepmother and the daughter she brought to the marriage. Lastly, she made a very emotionally charged account of her relationship with her boyfriend, who was considered to be a pillar of support.

Aim of the therapeutic process: to develop an assertive posture faced with relationships, raising the patient's self-esteem and lessening the feeling of inferiority, so that she would cease to be subjected to external impositions.

Therapist: a 24-year-old woman, having graduated one year previously, and with the same period of clinical experience. The psycho-therapeutic process took place under supervision in Brief Adult Psychotherapy, conducted by one of the study's authors, who had nearly 25 years of clinical experience. The treatment was carried out in the graduate school clinic at the university in which the study was conducted.

Tools

Therapeutic Interventions Classification - Classification adopted by Yoshida, Gatti, Enéas and Coelho-Filho (1997), comprising 14 types of intervention that are either Expressive, Neutral or Supportive in nature. All the interventions conducted during the psychotherapy are analyzed and classified according to the meaning revealed through each and which relates to one of the following definitions:

1. Interpretation - brings to the conscious mind something that was previously unconscious;

2. Confrontation - identifies something which the patient is downplaying or avoiding;

3. Clarification - reformulating or assembling the patient's words to make them more coherent;

4. Highlighting - showing relationships between data;

5. Encouragement to elaborate - request for more information;

6. Empathic validation - demonstrates the therapist's empathic synchronicity;

7. Recapitulation - resuming the essential points of the session or treatment;

8. Advice and praise - recommending and reinforcing attitudes;

9. Affirmation - succinct comments supporting the patient's comments and attitudes;

10. Interrogation - consulting and evaluating the patient's consciousness;

11. Providing information - clarifying technical aspects of which the patient is unaware;

12. Interrupted interventions - beginning of psychotherapist intervention interrupted by the patient;

13. Meta-intervention - aiming to clarify the reason for carrying out a different intervention at that point in the session or treatment;

14. Providing a framework - interventions related to the aspects of the therapeutic framework.

This form of intervention enables an estimate to be made of the degree of support and expressivity of all the interventions, as they are classified according to their nature within a continuum in which interventions directed towards the relationship or focusing on transference, are more expressive (like Interpretation) and interventions that do not focus on transference are more supportive (like Advice and praise), moving on through interventions which are Neutral in nature, located in the center of the Expressive-Supportive continuum. Accordingly, interventions nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 are classified as being expressive in nature while interventions nos. 6, 8 and 11 are supportive and interventions nos. 5, 9, 10, 13 and 14 are considered to be neutral. Finally, intervention no. 12 is not classified, as it relates to an interrupted intervention. In the present study, only the first two dimensions (expressive and supportive) were adopted for the purpose of evaluation, as these aim to estimate the degree of expressivity and support, in each phase of the process.

Working Alliance Inventory Short - Observer Version (WAI-S-O; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989), translated into Portuguese by Machado and Horvath (1999). This tool is composed of twelve items that aim to evaluate the Therapeutic Alliance (TA) by observers outside the therapeutic process, grouped into 3 dimensions:

(a) Aims - this refers to the understanding between therapist and patient with regard to the objectives of the psychotherapy with the aim of promoting changes; (b) Task - this refers to the activities undertaken by the therapist and patient to mobilize changes; and (c) Bond - this refers to the bond between therapist and patient which involves trust, respect and commitment to the therapeutic task. The gross scores for the dimensions and the total gross WAI-S-O score are obtained by adding together the points awarded, on a Likert-type scale that goes from 1 to 7, according to the intensity of the positive response. It should be emphasized that this tool does not rely on studies that present interpretative norms, nor cut-off points that classify different levels of therapeutic alliance. Nevertheless, it is considered that high scores in the respective dimensions that make it up indicate a better quality of therapeutic alliance.

Procedure

A complete Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (BPP) process was evaluated on an adult individual being treated in the graduate school clinic, which was video-recorded with the prior formal authorization by way of a Free and Informed Consent Form, by both of the study's participants: patient and psychotherapist. The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the university where the study was conducted (CEP 1165/09/2009 and Certificado de Apresentação para Apreciação Ética [CAAE] 0063.0.272.000-09). Authorization was also obtained from those in charge of the institution to use the material to be analyzed. The sessions were transcribed in full, aiming to observe the criteria presented by Mergenthaler and Stinton (1992) for psychotherapy material, aiming to remain faithful to the text and fully preserve the subject's intonation and inflections, in order to ensure access to the material grouping for the proposed evaluations.

The process was divided into initial, medial and final phases. The first three sessions correspond to the first phase of the initial evaluation. Here, a therapeutic framework is established as well as the psychotherapist's efforts being directed towards the understanding of the dynamics of the patient's functioning. The medial phase, or the unfolding of the process, encompasses sessions 4 through 7. This step is marked by focused work and by the more or less directed activity of the psychotherapist, depending on the intervention strategy he/she has chosen to employ. In addition, a positive alliance is sought linked to the strong motivation for change. In the final phase, sessions 8 through 11, importance is given to the closing work in which the main concern is to reprise the experiences which the patient obtained during the process, allowing her to incorporate the gains obtained and to acquire greater autonomy in respect of the resolution of the difficulties presented at the start (Yoshida & Enéas, 2013). Based on the transcriptions, the psychotherapist's interventions were classified in all sessions and the therapeutic alliance was evaluated in sessions 3, 7 and 10, fulfilling the methodological specifications of the different stages of the process.

All the analyses were preceded by the consensus of four independent judges, members of the study group, familiarized with the tools employed: three doctors in psychology, with 35, 34 and 15 years of clinical experience, respectively, and a psychology doctorate student with five years of clinical experience. Calculating a simple agreement between them, 80% was obtained for the analysis of therapeutic interventions and 100% for the analysis of the Therapeutic Alliance.

Results

The psychotherapist's verbal interventions, expressive and supportive in nature, were considered during each session. These verbal interventions are shown in Table 1, along with the frequency of each intervention and the total number of interventions per session.

Table 1 shows the distribution with regard to the nature of the interventions conducted in each phase of the process. A predominance of Expressive interventions can be observed in the Initial and Medial phases. In the Final phase, on the other hand, the Expressive and Supportive interventions are almost on a par. In the initial phase of the process, the number of interventions was lower than in the other stages (medial and final phase). Expressive interventions were predominant, especially the Confrontation (n=37) and Recapitulation (n=34) types. A high frequency of Empathic Validation intervention (n=56), supportive in nature, can also be observed. In the second stage of the process, the expressive Confrontation type of intervention continues to dominate (n=54) and there was an increase in Highlighting (n=56). As far as supportive interventions are concerned, the leading type was Empathic Validation (n=95). Lastly, the final phase was distinguished by the high number of expressive interventions of the following types: Confrontation (n=66), Clarification (n=42), Highlighting (n=37) and Recapitulation (n=52) and also by the significant number of supportive interventions, as follows: Empathic Validation (n=92), Advice and praise (n=59) and Providing information (n=47).

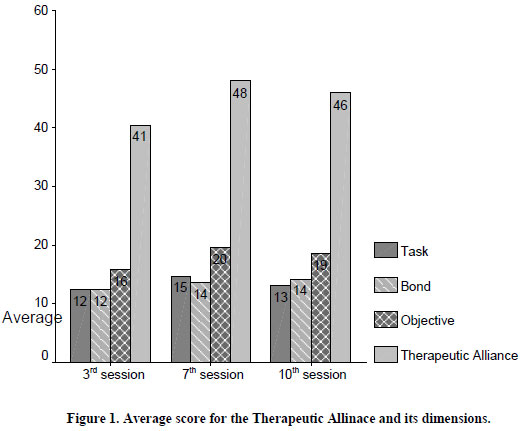

Figure 1 displays the average scores obtained for the therapeutic alliance and the respective dimensions in the different stages of the process, observing the evolution of the quality of therapeutic alliance between the third (41) and seventh session (48), and a modest reversal when compared to the tenth session (46) when evaluating the total score. As for the different therapeutic alliance dimensions: Task, Bond and Objective, the same movement can be observed, an increase in the scores exhibited between the third (12/12/16) and seventh sessions (15/14/20) accompanied by a slight reduction in the tenth session (13/14/19), respectively.

Discussion

As far as the interventions are concerned, both the initial and the medial stages of the process were differentiated by the higher frequency of expressive interventions (62.5% and 57.6%, respectively), and the two types achieved equilibrium in the final phase (50.7% and 49.3%). In similar vein, Yoshida et al. (2009) found, in their study of a brief psychodynamic psychotherapy process in an adult patient, a rather expressive posture on the part of the psychotherapist, as early as the second session. This posture continued into the medial phase. In the final phase, a complementary posture was observed on the part of the psychotherapist, offering help and support as well as using expressive interventions. Despland et al. (2001) noted that supportive interventions are not sufficient to build a good therapeutic alliance and that an array of expressive interventions, specific to each level of the patient's defensive functioning, are required to optimize the development of the alliance.

Despite the initial phase having been largely expressive, a close look at the first session reveals Empathic Validation (n=15) as the most frequent intervention. This may indicate that the initial objective of this session was to establish a positive working alliance as well as to carry out a task that is inherent to brief processes, in which the psychotherapist actively seeks to glean information on the patient (Simon, 1989; Yoshida & Enéas, 2013; Younes, Lessa, Yamamoto, Coniaric, & Ditzz, 2010). According to Figure 1, the therapeutic alliance is not yet fully consolidated in this phase and an increase in the Empathic Validation type of intervention, throughout the second (n=17) and third (n=24) sessions, suggests an intention to strengthen the alliance and, accordingly, make it possible for the patient to accept the Expressive form of intervention (Luborsky, 1984). However, in the second and third sessions, interventions of the Clarification and Recapitulation type were already in prominent position, demonstrating that the psychotherapist was attempting to summarize the essential points of this stage of evaluation in which aspects that the patient had previously been avoiding, must have been apparent.

In the medial phase, the expressive interventions prevailed, especially those of the Confrontation type (n=54), which saw an increase in this phase of the process, and the occurrence of Interpretation (n=7) in all sessions. It is assumed that these interventions were used with the aim of expanding the patient's consciousness, through the identification of her unconscious conflicts and the demonstration of the relationship between her current difficulties, as expressed in her complaint, and her conflicts of a psychological nature, which were established throughout her development. Also with regard to the medial phase, what is conspicuous is the high number of Empathetic Validation interventions (n=95), employed in all sessions, associated with other supportive interventions. It can be seen that the therapeutic alliance is already consolidated in this stage and the synchronicity between patient and psychotherapist, observed in the types of intervention, is probably due to the latter's concern with continuing to strengthen the bond already established in the initial phase of the process. This meets with the theoretical expectations that a good bond established between them could generate a relationship of mutual trust and commitment, which contributes positively to the development and success of the treatment (Constantino, 2012; Santibáñez Fernandez et al., 2008).

With regard to the final phase of the process, it can be seen that the psychotherapy gradually acquired a more supportive expression, arriving at a point of equilibrium between the two extremes. One possibility is that, in the final phase of the psychotherapy, there was greater expression and communication about the patient's core relationship conflict (fear of being abandoned) and, therefore, that it has become necessary to pay special attention to the process of separation and closure of the psychotherapeutic process. These aspects may also be reflected in the slight decrease in the therapeutic alliance, as in this phase of the process unconscious symptom-related conflicts tend to be rekindled such as, for example, the fantasizing of being abandoned by her parents. The explanation for this content demands of the psychotherapist, not only expressive interventions but also a solid, supportive base, so that the patient accepts these formulations and associates these childhood conflicts with difficulties of transference (Enéas & Rocha, 2011).

Another point which should be highlighted is the increase in the use of the expressive intervention of the Recapitulation type (n=20) in the 11th session, as well as the increase of two supportive interventions, thus far little used, such as Advice and Praise (n=20) and Providing Information (n=20). It is possible to infer that the psychotherapist sought to help her to overcome anxieties raised in the closing process and, in this regard, it may be said that the satisfactory outcome of this stage of the process will depend on the formulation of a significant patient conflict (Coelho-Filho, 1997; Luborsky, 1984; Yoshida & Enéas, 2013). These findings confirm the point of view that any psychotherapy can only be considered complete after diminishing anxieties raised in this stage of the process (Enéas & Rocha, 2011).

Moreover, it should be stressed that, in relation to the therapeutic alliance, specifically in the "objective" dimension, there was a prevalence of higher scores in the different phases evaluated, probably because this was a BP, a mode in which the process objectives are revisited, from beginning to end, via procedures such as therapeutic planning, review of the process medium and closure work (Enéas & Rocha, 2011; Yoshida & Enéas, 2013). This concurs with the hypotheses raised by Horvath (1994) that the therapeutic alliance in the initial phases of therapy would largely be indiscriminate and generic, whereas over the course of treatment, the importance of each of its dimensions would be perceived as a result of the proposed psychotherapeutic model.

Closing Remarks

As the aim of this study was not to establish cause and effect relationships between the therapeutic interventions in each phase of the process and the quality of the therapeutic alliance, it can be seen that the nature of the interventions and the therapeutic alliance modulated according to the characteristics inherent to each phase of the process, particularly the closure stage (Krause et al., 2007; Krause et al., 2006). The greater expressiveness, in the initial and medial phases, may be due to the active posture of the psychotherapist (Yoshida & Enéas, 2013), seeking to make conscious the unconscious aspects associated with the complaint presented by the patient. In the closing phase, the considerable reduction in the use of expressive interventions can be observed, as it is possible to repackage the patient's relational conflict in her relationship with the therapist, also requiring supportive work from the latter. In this vein, Enéas and Dantas (2011), basing themselves on the Kernberg study, stated that expressive psychotherapy contributes heavily towards elaborating conflict, as well as towards the strengthening of the patients' conscious mind.

In addition to the modulations in the therapeutic alliance and the interventions having been able to modulate in accordance with the tasks and objectives of the different stages of psychotherapy, the therapeutic alliance may have modulated according to the therapist's interventions. In this regard, Gelso (2015) states that if the true relationship between therapist and patient is the basis of the relationship as a whole, then the working alliance (the author prefers this designation) is what most directly makes it possible for the psychotherapeutic work to be performed, and thus the interventions are also chosen in order to ensure that the quality of the alliance is not lost and that results can be achieved.

This study does have its limitations, one of them being the fact that the analyses were planned a posteriori the performance of the psychotherapeutic process, which made it impossible to triangulate the evaluations and the response to self-report measures, both for the patient and for the psychotherapist. The performance of case studies using qualitative and quantitative methods, for example, involving the evaluation of results, may help to bolster the results found. Yoshida (2008) considered that, in case studies, the clinical significance of the change in psychotherapy may be determined by self-report measures. At this point, a number of issues may be raised, such as the impact of the intervention type on the patient's process of change, the weighting of patient conditions (diagnosis, expectations regarding the psychotherapy, to name but two) on the development of the therapeutic alliance and on the course of the psychotherapy.

References

Bernecker, S. L., Levy, K. N., & Ellison, J. D. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relation between patient adult attachment style and the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 24(1),12-24. doi:10.1 080/10503307.2013.809561 [ Links ]

Busseri, M. A., & Tyler, J. D. (2003). Interchangeability of the Working Alliance Inventory and Working Alliance Inventory, Short Form. Psychological Assessment, 15(2),193-197. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.193 [ Links ]

Coelho-Filho, J. G. (1997). Término em psicoterapia dinâmica breve. In C. D. Segre (Ed.), Psicoterapia breve. São Paulo, SP: Lemos. [ Links ]

Constantino, M. (2012). Believing is seeing: An envolving research program on patients' psychotherapy expectations. Psychotherapy Research, 22(2),127-138. doi:10.1080/10503307.2012.66 3512 [ Links ]

Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance-outcome relationship: A restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(7),642-649. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.002 [ Links ]

Despland, J. N., Roten, Y., Despars, J., Stigler, M., & Perry, J. C. (2001). Contribution of patient defense mechanisms and therapist interventions to the development of early therapeutic alliance in a Brief Psychodynamic Investigation. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 10(3),155-164. [ Links ]

Eells, T. D. (2007). Generating and generalizing knowledge about psychotherapy from pragmatic case studies. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 3(1),35-54. doi:10.14713/pcsp.v3i1.893 [ Links ]

Enéas, M. L. E., & Dantas, M. S. (2011). Critérios de indicação de psicoterapia breve em clínica-escola com pacientes difíceis. In S. F. S. Cavalini & C. Batista (Eds.), Clínica psicodinâmica: Olhares contemporâneos (pp. 153-170). São Paulo, SP: Vetor. [ Links ]

Enéas, M. L. E., & Rocha, G. M. A. (2011). Momentos decisivos em psicoterapia breve: Manejo do término. In S. F. S. Cavalini & C. Batista (Eds.), Clínica psicodinâmica: Olhares contemporâneos (pp. 129-144). São Paulo, SP: Vetor. [ Links ]

Falkenström, F., Granström, F., & Homqvist, R. (2014). Working alliance predicts psychohterapy outcome even while controlling for prior symptom improvement. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2),146-159. doi:10.1080/10503307.2013.847985 [ Links ]

Fiorini, H. J. (2004). Teoria e técnica de psicoterapias. São Paulo, SP: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Gabbard, G. O. (2006). Psiquiatria psicodinâmica na prática clínica (4. ed.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Gelso, C. (2015). A tripartite model of the therapeutic relationship: Theory, research and practice. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2),117-131. doi:10.10 80/10503307.2013.845920 [ Links ]

Horvath, A. O (1994). Empirical validation of Bordin's Phantheoretical Model of the Alliance: The Working Alliance Inventory Perspective. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The Working Alliance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 1-9). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2),223-233. [ Links ]

Khater, E., Peixoto, E. M., Honda, G. C., Enéas, M. L. E., & Yoshida, E. M. P. (2014). Momentos chave e natureza das intervenções do terapeuta em Psicoterapia Breve Psicodinâmica. Psico-USF, 19(2),233-242. doi:10.1590/141382712014019002010 [ Links ]

Krause, M., de la Parra, G., Arístegui, R., Dagnino, P., Tomicic, A., Valdés, N., ...Ben-Dov, P. (2007). The evolution of therapeutic change studied through generic change indicators. Psychotherapy Research, 17(6),673-689. doi:10.1080/10503300601158814 [ Links ]

Krause, M., de la Parra, G., Arístegui, R., Dagnino, P., Tomicic, A., Valdés, N., ...Ramírez, I. (2006). Indicadores genéricos de cambio en el proceso psicoterapéutico. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 38(2),299-325. [ Links ]

Lhullier, A. C., Nunes, M. L. T., & Horta, B. L. (2006). Preditores de abandono de psicoterapia em pacientes de clínica-escola. In E. F. de M. Silvares (Ed.), Atendimento psicológico em clínicas-escola (pp. 229-256). Campinas, SP: Alínea. [ Links ]

Luborsky, L. (1984). Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: A manual for supportive-expressive treatment. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Luborsky, L. (2000). A pattern-setting therapeutic alliance study revisited. Psychotherapy Research, 10(1),17-29. doi:10.1080/713663591 [ Links ]

Machado, P. P., & Horvath, A. (1999). Inventário da Aliança Terapêutica: Versão portuguesa do Working Alliance Inventory. In M. R. Simões, L. S. Almeida, & M. Gonçalves (Eds.), Provas psicológicas em Portugal (Vol. 2). Braga, Portugal: Sistemas Humanos e Organizacionais. [ Links ]

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68,438-450. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438 [ Links ]

Mergenthaler, E., & Stinton, C. H. (1992). Psychotherapy transcription standards. Psychotherapy Research, 2,125-142. [ Links ]

Meyer, S. B. (2006). Metodologia de Pesquisa da Psicoterapia em Clínicas-Escola. In E. F. de M. Silvares (Ed.), Atendimento psicológico em clínicas-escola (pp. 23-41). Campinas, SP: Alínea. [ Links ]

Muran, J. C., & Barber, J. P. (2010). The therapeutic alliance - An evidence-based guide to practice. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Prado, O. Z., & Meyer, S. B. (2004). Relação terapêutica: A perspectiva comportamental. Evidências e o Inventário de Aliança de Trabalho (WAI). Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 6(2),201-209. [ Links ]

Prochaska, J. O. (1995). An ecletic and integrative approach: Transtheoretical therapy. In A. S. Gurman & S. B. Messer (Eds.), Essencial Psychotherapies: Theory and practice (pp. 403-440). New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Safran, J., Muran, J. C., Demaria, A., Boutwell, C., Eubanks-Carter, C., & Winston, A. (2014). Investigating the impact of alliance focused training on interpersonal process and therapists' capacity for experiential reflection. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3),269-285. doi:1080/10503307.20131080/10503307.2013.2013.874054

Santibáñez Fernandez, P. M., Román Mella, M. F., Lucero Chenevard, C., Espinoza García, A. E., Irribarra Cáceres, D. E., & Müller Vergara, P. A. (2008). Variables inespecíficas en Psicoterapia. Terapia Psicológica, 26,89-98. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082008000100008 [ Links ]

Simon, R. (1989). Psicologia Clínica Preventiva: Novos fundamentos. São Paulo, SP: Editora Pedagógica e Universitária. [ Links ]

Slonim, D. A., Shefler, G., Gvirsman, S. D., & Tishby, O. (2011). Changes in rigidity and symptoms among adolescents in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 21(6),685-697. doi:10.1080/10503307.2011.602753 [ Links ]

Tishby, O., & Vered, M. (2011). Countertransference in the treatment of adolescents and its manifestation in the therapist-patient relationship. Psychotherapy Research, 21(6),621-630. doi:10.1080/10503307.2011.598579 [ Links ]

Tracey, T. J., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, (3),207-210. [ Links ]

Wiseman, H., & Tishby, O. (2014). The therapeutic relationship: Multiple lenses and innovations. Introduction to a special section. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3),251-256. doi:10.1080/10503307.2014.892648 [ Links ]

Yoshida, E. M. P. (2008). Significância clínica de mudança em processo de psicoterapia psicodinâmica breve. Paideia (Ribeirão Preto), 18(40),305-316. doi:10.1590/S0103-863X2008000200008 [ Links ]

Yoshida, E. M. P. (2012). Psicoterapias psicodinâmicas. In M. E. N. Lipp & E. M. P. Yoshida (Eds.), Psicoterapias breves nos diferentes estágios evolutivos (pp. 1-17). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Yoshida, E. M. P., & Enéas, M. L. E. (2013). A proposta do Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisa em Psicoterapia Breve para Adultos. In E. M. P. Yoshida & M. L. E. Enéas (Eds.), Psicoterapias psicodinâmicas breves: Propostas atuais (3. ed., pp. 231-269). Campinas, SP: Alínea. [ Links ]

Yoshida, E. M. P., Elyseu, S., Jr., Silva, F. R. C. S., Finotelli, I., Jr., Sanches, F. M., Penteado, E. F., ...Enéas, M. L. E. (2009). Psicoterapia psicodinâmica breve: Estratégia terapêutica e mudança no padrão de relacionamento conflituoso. Psico-USF, 14(3),275-285. doi:10.1590/S141382712009000300004 [ Links ]

Yoshida, E. M. P., Gatti, A. L., Enéas, M. L. E., & Coelho-Filho, J. G. (1997). Aliança Terapêutica, Transferência e Motivação num processo de Psicoterapia Breve. Mudanças, 7,141-154. [ Links ]

Younes, J. A., Lessa, F., Yamamoto, K., Coniaric, J., & Ditzz, M. (2010). Psicoterapia Breve Operacionalizada e crise por expectativa de perda: Um estudo de caso. Psicologia Argumento, 28(63),303-309. [ Links ]

Recebido: 10/02/2015 Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Evandro Morais Peixoto

Rua Liliane Regina, 03, Vila Cretti

Carapicuíba, SP, Brazil 06386-300

Phone: (11) 98089- 4423

E-mail: epeixoto_6@hotmail.com

1ª revisão: 18/08/2015

2ª revisão: 14/09/2015

Aceite final: 12/10/2015

Financing: Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

texto en

texto en