Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.25 no.4 Ribeirão Preto dic. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2017.4-11Pt

ARTIGOS

Development of social skills in female crack users: multiple case study

Jéssica Limberger; Ilana Andretta

Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Studies indicate a relationship between low levels of social skills and drug use, but do not contemplate the meanings for female crack users. Thus, the aim was to understand the development of social skills in the life trajectory of these women. This was a qualitative, multiple case study with cross-case synthesis. Data were collected by the researcher in two stages, the first consisted of the application of the socio-demographic data and drug use questionnaire, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Social Skills Inventory, Cognitive Screening of the WAIS-III and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders. In the second step, the Clinical Interview about Life Trajectory and Social Skills was used. Three women participated in this study. All presented difficulties in social skills since childhood, with repertoires acquired through inadequate models of social interactions with family, school colleagues and peers. Comorbidities may have hindered the use of social skills, which showed deficits in the women with borderline personality disorder. The clinical interview allowed a deeper analysis of the data obtained through the IHS-Del Prette. It indicated that the comorbidities were considered in the evaluation of the social skills and that interventions promoted these skills during the treatment for drug use.

Keywords: Social skills, women, crack cocaine, disorders related to substance use, multiple case study.

Social skills are different classes of behavior that are part of the repertoire of the individual, allowing the person to deal adequately with the demands of interpersonal situations (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014). These skills are necessary conditions, although not sufficient, for social competence, which is a set of successful behaviors that contribute to an increase in gains and reduction of losses for the person him/herself and the people involved in the interpersonal situation (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2013). During the life cycle, social skills are related to improved quality of life, in that they enable more productive and satisfying interpersonal relationships (Feitosa, 2013; Terroso, Pedroso, & Kurle, 2015).

The main social skill classes and subclasses are: social skills of communication (starting and maintaining conversation and giving and receiving feedback), social skills of civility (expression of courtesy in accordance with the rules and culture of the group), assertive social skills of coping, rights and citizenship (expression of views and rights in different contexts), empathic social skills (expression of support and solidary sharing), social skills of work (decision making, conflict mediation and group coordination) and social skills to express positive feeling (maintenance of friendly relationships, love and solidarity; Del Prette & Del Prette, 2013).

Social skills are acquired over the course of the development, from social interaction situations (Terroso et al., 2015). Childhood is a unique step in learning these skills, as behavioral plasticity is characteristic of this phase (Del Prette, Ferreira, Dias, & Del Prette, 2015). In adolescence, due to greater contact with peers, there is a need for new skills in interactions and social skills relating to the capacity for refusal, in peer pressure situations, of involvement in risk behaviors, such as drug use and violence (Vorobjov, Saat, & Kull, 2014; Wagner & Oliveira, 2015). In adult life, the level of complexity of the use of social skills increases, according to the demands of different contexts of interaction: family, work, friends, and others (Del Prette et al., 2015; Limberger & Andretta, 2015a).

From childhood, and in the other stages of development, there are factors that may hinder the use of social skills, such as negative experiences in social interactions, lack of models for learning, and clinical characteristics, such as depression and anxiety (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014; Fernandes, Falcone, & Sardinha, 2012; Segrin, 2010; Terroso et al., 2015). Difficulties in the use of social skills, when they become recurrent, may generate deficits. These deficits can be related to acquisition (non-occurrence of social skills in the demands of the environment), performance (occurrence of a specific skill less frequently than expected in the demands of the environment) and/or fluency (occurrence of the skill with lower proficiency than expected (Angélico, Crippa, & Loureiro, 2006).

Deficits in social skills result in psychological distress and behavioral problems, such as drug use (Andretta, Limberger, & Schneider, 2016; Feitosa, 2013; Schneider, Limberger, & Andretta, 2016). The literature has already identified specific deficits in drug users compared with non-users. According to a Portuguese study with 124 users of illicit drugs, deficits in social skills of assertiveness and coping with risk, as well as conversation and social resourcefulness were identified (Sintra, Lopes, & Ant, 2011).

In turn, deficits in self-exposure to strangers and new situations and self-control of aggressiveness in aversive situations were described in adolescent marijuana users, with significant differences in relation to the control group, in a Brazilian study with 98 participants (Wagner & Oliveira, 2015).

In the context of crack use, a Brazilian study with 63 female crack users showed deficits in conversation and social resourcefulness, self-exposure to strangers and new situations and self-control of aggressiveness in aversive situations (Limberger & Andretta, no prelo). In this study, associations were observed between psychiatric comorbidities and social skills. Women with Major Depressive Episode presented significantly lower scores in self-control of aggressiveness and the deficit in social skills was associated with having Borderline Personality Disorder. From this perspective, in the evaluation of social skills, it is necessary to consider psychiatric comorbidities, as these may also be hindering the performance of such skills (Limberger, 2016).

Studies that address the social skills and the use of drugs are predominantly quantitative studies, as shown by a systematic review of the national and international literature, which analyzed 13 articles on the topic (Schneider et al., 2016). Of the articles analyzed, all were quantitative, with no article specifically addressing the social skills of the female crack user population. Thus, there is still a gap in the literature regarding the comprehension of social skills in drug users from a qualitative perspective.

Considering that the quality of interpersonal relationships (living in an unstable family environment) and the contexts of interaction (being associated with users and suppliers) are risk factors for the use of crack in women (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2014), there is a need to analyze the role of social skills in this population, since childhood. Thus, the following research problem was proposed: "How do the social skills develop during the life of female crack users?". This study aimed to comprehend the development of social skills in the life cycle of female crack users.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative, cross-sectional, multiple case study (Yin, 2010). The COREQ - consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research, was used to ensure higher quality in the study. The 32 items of the checklist were followed, which are divided into three areas: study team and reflexivity, study design and analysis of findings (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Participants

The criteria established for participation in the study were: women aged between 18 and 59 years, with Substance Use Disorder (crack) according to THE DSM-5 (APA, 2014), hospitalized between the seventh and the fifteenth day of the hospitalization, and with deficits in social skills of at least two factors, according to the Social Skills Inventory (IHS) score. Participants with psychotic syndrome (verified by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) and cognitive impairment (verified through the vocabulary and cubes subtests of the Cognitive Screening of the WAIS-III - Wechsler, 1997) were excluded. These instruments will be detailed in the "Instruments" section.

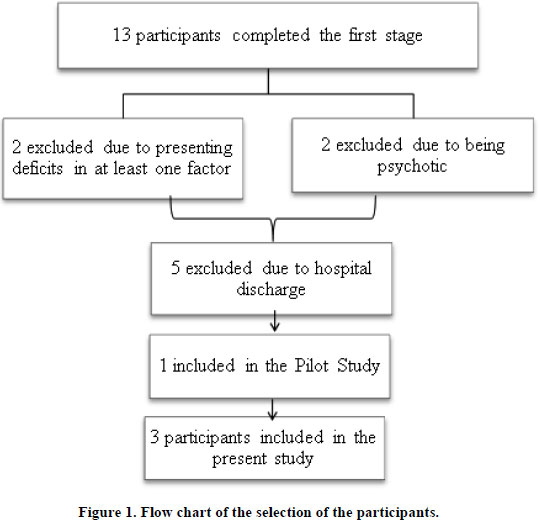

The selection of participants was taken from a sample of 13 women who were hospitalized. The flowchart of the participant selection is presented in Figure 1.

Three women participated in this study: Isabel, Deborah and Rita (fictitious names).

Participant 1. Isabel. She was aged 36 years, divorced and had incomplete Higher Education. She was unemployed and in economic class D. Isabel first tried crack at 29 years of age.

Participant 2. Deborah. She was aged 30 years, single and had incomplete High School Education. She was unemployed and in economic class D. Deborah first tried crack at 27 years of age.

Participant 3. Rita. She was aged 28 years, single and also had incomplete High School Education. She worked as a manicurist before the hospitalization and was in economic class C1. Rita tried crack at 18 years of age.

Isabel and Rita were interviewed in hospitals in the northwest region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul and Deborah was interviewed in a hospital of the metropolitan region of Porto Alegre (RS).

Instruments

Sociodemographic Data and Drug Use Questionnaire. This was developed by the research group "Behavioral Cognitive Interventions: Teaching and Research". It consists of open and closed questions regarding sociodemographic and family data (age, education, cohabitation situation, which relatives have or had problems with the use of any drugs, etc.), Brazil Criteria of Economic Classification of the Brazilian Association of (Market) Research Companies (ABEP, 2015), data on drug use (when tried for the first time, frequency and intensity of use in the previous year) and DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2014) for the diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder.

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). This is a clinical interview compatible with the diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2002) that evaluates the presence of psychotic syndrome and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as the risk of suicide. It was developed by Sheehan et al. (1998) and validated for Brazil by Amorim (2000). In the validation, the Kappa indices demonstrated reliability in the diagnostic categories (0.86 to 1.00) and in the psychotic disorders (0.62 to 0.95; Amorim, 2000).

Cognitive Screening of the WAIS-III. This test is for the exclusive use of psychologists and was developed by Wechsler (1997) and adapted and standardized to Brazil by Nascimento (2004). The screening includes vocabulary and cubes subtests with satisfactory alpha values α = 0.92 and α = 0.83 respectively). The vocabulary subtest evaluates verbal comprehension, from words presented by the examiner, who should define them orally. The cubes subtest evaluates the perceptual organization through a set of two-dimensional geometric patterns that the subject should reproduce using cubes of two colors (Nascimento, 2004).

Social Skills Inventory (IHS). Developed by Del Prette and Del Prette (2001), also for the exclusive use of Psychologists, it characterizes the social skills in different situations: work, school, family and everyday (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2001). The inventory is self-reported, consisting of 38 items on a likert scale, with five points ranging from never or rarely to always or almost always. The IHS has Cronbach's alpha of 0.75 and test-retest reliability (r = 0.90; p = .001). Factor analysis revealed a five-factor structure that bring together social skills of: (a) self-assertion and coping with risk - indicates the ability to deal with situations that require assertion and defense of rights and self-esteem; (b) self-affirmation in the positive expression of affection - composed of skills such as praising and thanking for praise and defending another person in the group; (c) conversation and social resourcefulness - includes the social experience with the use of everyday relationship rules; (d) self-exposure to strangers and new situations - including situations of higher risk of an undesirable reaction from the other person, such as when approaching unknown people; (e) self-control of aggressiveness to aversive situations - refers to the expression of displeasure or anger in a socially responsible way (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2001).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-II). Developed by First, Gibbon, Spitzer and Williams (1997) and translated into Portuguese (Brazil) by Melo and Rangé (2008), it is a semi-structured interview, which seeks to identify personality disorders according to the DSM IV-TR (APA, 2002). In this study, Histrionic, Narcissistic, Borderline and Antisocial Personality Disorders were investigated.

Clinical Interview about Social Skills and Life Trajectory. This was developed by the researcher and her advisor, from a literature review on the use of drugs and social skills (Schneider et al., 2016). Furthermore, it was based in the theoretical and practical field of social skills, from the constructs of Del Prette and Del Prette (2001, 2014). The interview consists of a period of rapport, followed by open questions about the life history and social skills of conversation and social resourcefulness; positive expression of feelings; defense of rights; interaction with strangers and new situations; and reactions to aversive situations. Prior to the initial performance of the interview, it was evaluated by a third psychologist, with expertise in the area of social skills, who suggested changes. In addition, a pilot study was carried out with a female crack user, whose interview was conducted by the researcher in a hospital in the metropolitan area. From the pilot study, changes were made, such as making the questions more comprehensive and adapting the language in order to make the interview clearer and more understandable.

Ethical Procedures

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, under authorization number 012/2015, which is in accordance with international guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). After gaining consent from the hospitals, the consent of the participants was sought through personal contact at the hospital where they were hospitalized. They were invited to participate in the study, with an explanation of the study objectives and the voluntary nature of their participation and a guarantee of data confidentiality and anonymity. The consent form was read and explained individually for each participant, who, upon agreement, signed the two copies of the form, one copy remaining with the participant and the other with the researcher. The participants and their respective hospitals were offered the study results. The study had two data collection steps, therefore, there was a consent form for each step.

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected in three hospitals with inpatient beds for detoxification due to the use of crack, from the northwest and metropolitan regions of Rio Grande do Sul. These hospitals were linked to the Brazilian National Health System (SUS). The interviews were conducted individually, in rooms with only the researcher and the participant.

In the first stage, the instruments were applied in the following order: Socio-Demographic Data and Drug Use Questionnaire, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Cognitive Screening of the WAIS-III, Social Skills Inventory (IHS) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-II). In the second stage, the Clinical Interview on social skills and life trajectory was applied, being audio recorded. The interview was conducted by the researcher, who is a psychologist that, during the study period, worked with a scholarship for her MSc. The researcher gained experience in family care of drug users, during the four-year period in which she was an undergraduate, followed by the intensification of studies on drug use at the time of the research, with the supervision of her advisor regarding the performance of the interviews. The relationship of the researcher with the participants was established at the beginning of the study. Thus, the participants knew about the training of the researcher, about the institution performing the study and also about the aims of the study. However, the study hypotheses were not mentioned to the participants. In the two steps, no field notes were taken.

Data Analysis Procedures

Data from the first step were tabulated in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences - SPSS, version 20.0, by only one person, a member of the research group. The questionnaire was used to characterize each case. The MINI was corrected in accordance with the criteria set out in the interview in order to contemplate the presence of the identified diagnoses. With cognitive impairment being an exclusion criterion, the correction of the Cognitive Screening of the WAIS-III was performed by two independent judges, and if there was need for consensus, a third judge was included. From the subtraction of the weighted score of the vocabulary from the weighted score of the cubes, a difference of three points or more indicated cognitive impairment, according to Cunha (1993) and Feldens, Silva and Oliveira (2011). The correction of the Social Skills Inventory was carried out in a simplified way, based on the inversion of specific items followed by calculating the simple mean of the values obtained, according to the guidelines of Del Prette and Del Prette (2001). The interpretation of the score was based on the position, in percentiles, in relation to the reference subgroup of the same gender and age. Values in the 50th percentile indicate a median position, values above 75% indicate high factors in social skills and values below 25% indicate deficits in social skills (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2001). Finally, the correction of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-II) was performed considering the presence or absence of diagnostic criteria for each disorder explored in the interview.

Data from the second stage - Clinical Interview about social skills and life trajectory - were transcribed in full. Subsequently, each interview was read and re-read by the researcher, in order to identify recurring characteristics and information that addressed the study objectives. With this data, four guiding axes were created for the analysis, defined a posteriori. The first axis (a) corresponds to the childhood, the second axis (b) deals with adolescence, the third axis (c) contemplates the start of drug use, and the fourth axis (d) deals with the current moment of life. The analysis of the social skills was carried out in a cross sectional way in each axis. Finally, seeking to ensure higher quality of analysis, the similarities and particularities of the cases were investigated from the cross-case synthesis, according to Yin (2010).

Results and Discussion

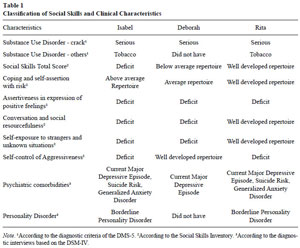

From the correction of the instruments of the first step, the following data were identified, as shown in Table 1.

Tabela 1 - Clique para ampliar

Case 1 - Isabel

Isabel was 36 years of age. At the time of the study she was unemployed, her last job was as a Nursing Technician, two years previous. She had four daughters aged 21, 13, 12 and 10 years, with the three younger ones living with the father (ex-husband of Isabel) and the eldest daughter living with her boyfriend and their daughter. The hospitalization was voluntary and her motivation for treatment was due to the large impairments from crack use, reporting a desire to return to her normal life.

Childhood. Isabel reported having a good childhood: "I was a child who had everything, my mother gave me everything". However, she referred to constant fights with her mother and the lack of a father, who was a salesman and traveled a lot. Regarding the disagreements with her mother, she said: "I think I could never show my mother what I was really feeling or how I felt". At the start of school and in the other school years, Isabel had just one friend, and if she was away she "felt lost". She pointed out that her way of behaving in childhood was "quiet and silent". For Isabel, the courses that she took in childhood contributed to her shyness being less intense. She mentioned early participation in the church choir and in painting courses. She also pointed out that despite the shyness she had always been "polite and friendly".

Adolescence. As she grew, some difficulties of interaction intensified, especially with regard to the group of friends. She said her mother would not let her leave the house and her friends did not like to come to her home because of the aggressiveness of his mother. She recalled: "My friends said: Ah ... we cannot go to Isabel's house". Fearing the mother, she reported that she began to date secretly. At age 14 she became pregnant, and her parents forced her to marry. At that point, she left home and did not have the help of her parents any more, leaving the courses she attended. She said that she could not ask them to keep paying for the courses and financially supporting her, because she felt too embarrassed. She also indicated other difficulties of interaction, such as asking questions of strangers.

Drug Use. Isabel constantly saw her mother drinking alcohol, especially when Isabel's father was traveling. However, her mother never admitted to having a problem with the use of alcohol and did not seek treatment. Isabel's first drug experienced was with marijuana in a group of friends, due to fear that she would not be accepted in the group. She did not like the experience, because the drug made her feel bad and caused nausea. She also tried cocaine and due to "a problem in the nose" she never used it again. In these circumstances, she says she could say no to these drugs, as both made her feel bad.

Isabel tried crack at age 28, when she separated from her husband and began dating an alcohol and cocaine user. She reported that she was in a group of people using cocaine and marijuana and felt "excluded" because she did not use these drugs as they made her "feel bad". On this day, a neighbor arrived and offered her crack and she accepted. Isabel reported that first she began to use while her boyfriend was using cocaine, however, then her boyfriend also started using crack, both of whom had developed a pattern of heavy use. Thus, Isabel could not complete the degree in the final year of the course and was fired from her job.

In the context of drug use, Isabel highlighted the difficulty of refusing crack from her boyfriend:

When my boyfriend came with a rock it felt like I had to share that moment with him. I had to have that time with him ... I even tried to refuse and said to him one day: "smoke in another room because I do not want to see you smoking". But then he came to the door asking for something and I said, "ok then come in here".

This difficulty was also in relation to other users, due to their mockery.

When I refused a smoke from someone, they always mocked me. They said: "wow, she's refusing a piece of rock!" And often they filled me with drugs, I could not manage to smoke more. I ended up giving it to the others..

Adulthood Isabel perceived a certain evolution in the interaction with people in adulthood.

According to her: "I think, over time, I was being different, because when I was younger I was much quieter. Then with the technical course and then university, when I had to start presenting work in class, I began to talk more". She recalls a situation in which a teacher asked her to present a piece of work without reading, and when she did, the teacher praised her.

Some similarities to her eldest daughter were perceived by Isabel:

She's just like me ... If we go into a store to buy clothes, she is embarrassed to ask for things for her. Then she nudges me. So I have to ask for it, understand? Even now, that she is over 18. It's funny that she is still embarrassed. I have to help, step in for her, even though I also experienced this several times.

In the context of work, Isabel said there were difficulties in communication between her and her boss. In situations that required her to express displeasure, Isabel says she could not say what she was thinking, due to fear of the reaction that the person would have. "I think I've never been one to stick up for my rights". At the time of hospitalization, this difficulty also showed itself to be present:

It's frustrating, because sometimes there are things that bother me, like here in the hospital, when I want to be quiet in my corner and someone is talking ... but still, I keep answering politely and with a fake smile on my face to say that I'm listening to her and everything is fine.

At the time of hospitalization, Isabel characterized her interactions with cordiality and politeness. She stated that in situations where the cordiality was not reciprocated, she felt "as if she wanted to punch the person in the face".

Case 2 - Deborah

Deborah was 30 years of age, she was unemployed at the time before the hospitalization. Her last job was as a kitchen assistant, for three months. She lived with her four children, who were aged 12, 9, 6 and 3 years. The hospitalization was voluntary, because she wanted to be an example for her children. She had a sister who was taking care of her children during the hospitalization.

Childhood. Deborah reported having a good childhood:

My mother was a good person, we were bought up by her only. She took us to the playground, she always took us to school. I have two sisters who are also wonderful. My childhood was great, it was with the passage of time that I made mistakes.

At age five, Deborah's parents separated and from then on she had little contact with her father. When she was little and had to ask for something, Deborah stated: "I always ran to my mother for her to ask for me", being shy and "sheltered".

Adolescence. Deborah recalled adolescence as "a good time" while also reporting that she did not go out to parties: "My mother did not let me. She did not like it if we went out at night, she was afraid". In social situations, Deborah recalled that she always preferred people to initiate conversations and that they ask the questions, and then she would start to talk, because she thought that she "talked nonsense".

Drug Use. When Deborah was 12, she started smoking cigarettes. Seeing her mother smoking, she started smoking in secret. The use of crack occurred at age 25, two years after the death of his mother. At the time, her husband was in prison for selling drugs, and she experimented with crack through her sister-in-law who it to offered her. She said this was the only relationship she had with a "criminal" and that he had never offered her crack. The use of crack continued for eight months and then she went approximately three years without using, during which she had a partner who was not a user. After the separation from this partner, she started using crack again. According to her: "I threw him out of the house, saying that he was bothering me... But I think in my head, now thinking about it, that this was just an excuse, because I already had an urge to use". Due to the use of crack, Deborah pointed out that she lost friendships: "In the past they gave me a lot of attention. Today I talk to them and they exchange a few words and then say goodbye, 'I have to go somewhere, another time we will talk more'".

Adulthood. Deborah said she was still timid, behavior that is similar to that of her son:

My oldest kid is very shy. The others are not, they talk, they play with him, but he's always quiet in his corner. If you strike up a conversation with him, he talks. If not, he stays there very quiet. It is very similar for me.

She says she still preferring that others bring up an issue with her because she is "afraid to talk nonsense, to start talking about things that are not. So I prefer that other people start an topic for me to speak". Regarding interaction contexts, Deborah stated that she had difficulties:

Because, generally, no one wants to be near a person who uses drugs. No one will sit and chat with a user. It is difficult to relate to other people who do not use ... And I end up not making conversation, because usually we do not even want to talk more. You already know how you will be treated. So I don't seek it anymore.

In situations where she stops talking to people due to fear, Deborah highlighted:

I feel like I'm half-empty, right? Because then I do not talk, just listen. It's like the group with the psychologist, it is rare for me to open my mouth to speak, I just listen. I think: wow, if I say something I will talk nonsense. So I think a lot, that I will not talk because when I talk, I say something that doesn't make sense. So I just listen to them talking.

In situations of defense of her rights, she said that she was nervous: "But then I argue (laughs). I argue for my rights".

Case 3 - Rita

Rita was 28 years of age and before her hospitalization she worked as a manicurist. She lived with her children of two and eight years and with her partner. The hospitalization was voluntary, and what motivated her to seek treatment was recognizing that she was using too much, she was "finished".

Childhood. When talking about her history, Rita said her life "was never very good, I didn't like it, it's not good for me to remember". During the interview, she said:

I was born fighting because my mother tried to abort me twice and failed. At one year and three months, she threw me in the trash can. And I am here ... So I say, I fight, I turned into a lioness because I learned.

At ten years of age her father died and she was raised by her grandparents. At school, she said that friendships with colleagues were more distant and that often there were misunderstandings, leading to fights. In the family life, she reported constant arguments and shouting between her and her brothers.

Adolescence. During adolescence, Rita said she had always been "rude" when interacting with people, and that she fought with her brothers, considering only her older sister to be supportive. In adolescence, although she referred to many friends, she mentioned that she did not have anyone in times of difficulty: "I stayed on my own, I don't talk about problems, I keep them inside".

Drug Use. Rita remembers that her brother was smoking marijuana in front of her: "he blew marijuana in my face, until one day I tried it". With this, she tried marijuana at 16, using occasionally until 20 years of age. At 17, she tried cigarettes and continued smoking until she was 20. Rita worked as a prostitute from 20 to 21 years of age and began using cocaine "to stay awake and endure it". Soon after she stopped working as a prostitute, she tried crack "for no reason", from a friend:

A friend of mine smoked and went to my house. I asked her, what do you want with this? One day she got very stoned and asked me to get some for her, I said I'll go and get it and I think I'll get some for me too. Then I smoked but it did not do anything to me, I thought, I'll smoke another one. And I smoked another, and another and another.

Since then, Rita had intervals of up to two years in which she stopped using, however, eventually returned to use during the eight years of crack use.

Adulthood. In the day-to-day, Rita said that she complements people. For her, "the complement is a form of good manners, it is a way sometimes we get close to the person, make a bond". She also said that she praises the people because "they give things without expecting anything back", especially praising her children: "My daughter and my son are who I praise most ... as if they were the world's most beautiful children, the best in the world, I say they are the best kids in the world". In situations where she needed to ask for help, she turned to her sister that she trusts more and also asked for help from her husband, and when she did not ask for help for her sister or her husband, she preferred to ask for help from strangers: "Because those people you know, you help so many people you know, then when you need help, they turn their backs on you, they do not remember that you helped them once".

When Rita felt uncomfortable with something, she said she was "very rude". According to her: "Even a lion would be ashamed near to me, I try to do everything in a nice way, but if it does not work out like that, I lose it, I lose good judgment and nobody can stop me". In times when she needed to deal with anger, she said:

I keep away from people. I stand up, I hit a door, I speak loudly, as I say, "look, let's turn this off", if you have sound turned on, I turn it off and say "look, I do not want to have this turned on any more and that's it, finish the party, leave me very quiet" and I turn my back and leave.

The situations of difficulty dealing with anger were also expressed in the treatment: "I have already argued with the nurse, it made me want to get out of here at once".

Cross-Case Synthesis

The general characteristics of the participants show similarities in the use of crack in a serious way. Furthermore, in all three cases there were deficits in self-affirmation and expression of positive feelings and an average or above average repertoire in coping and self-assertion with risk.

Borderline Personality Disorder was identified in Elizabeth and Rita, who were also similar in the concurrent use of crack and tobacco and in the presence of the same comorbidities (Current Major Depressive Episode and Generalized Anxiety Disorder), as well as the risk of suicide. With this, it is understood that the presence of the Personality Disorder can lead to greater SS deficits, as was the case for Isabel, and greater aggressiveness in the style of response, such as with Rita. It is known that Borderline Personality Disorder is characterized by impulsivity and patterns of instability in interpersonal relationships (APA, 2014). However, it is not only the presence of personality disorder that defines possible relationships with a deficit in social skills. Thus, if new social interactions were developed in contexts that promote social skills (such as Social Skills Training), impulsivity might not be so intense or the participants might develop the class within the SS known as self-control of aggression (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2013). From the case of Deborah, who did not present any of the assessed personality disorders and had fewer psychiatric comorbidities compared to the other participants, it is clear that the main aspect was her shyness and fear of "talking nonsense". This fear of other people's judgment may be associated with the Current Major Depressive Episode that she presented. This comorbidity complicates the use of social skills and needs to be evaluated carefully (Segrin, 2010). In this context, Social Skills Training can contribute to improvements in depression, starting with easier social skills in order to stimulate the strengths of the participants (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014). A single case study of a patient with depression and suicidal ideation showed improvements after the completion of Social Skills Training (16 sessions, over a period of three months), which remained after a three month follow-up (Jansson, 1984).

In addition to the general characteristics, it was identified that in the childhood axis the cases shared specific difficulties in the use of social skills: Isabel and Deborah reported shyness in expressing their feelings and Rita had aggressive responses faced with some situations. Thus, it is clear that family background plays an important role in learning social skills, as they are primarily learned from the interpersonal relationships with the parents in childhood (Limberger & Andretta, 2015a). In the case of Rita, she stated: "I turned into a lioness because I learned", with her also reporting that she lived in an environment with constant fights and arguments. In this sense, the problems of the parents to adequately express both anger and displeasure constitute a model of inappropriate learning with regard to social skills for the children (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014).

The three cases share difficulties in social skills during adolescence, each with its specificity. Isabel and Rita continued with similar patterns to those of childhood. In childhood, Isabel reported difficulties in communicating with her mother and in adolescence she highlighted the difficulty in making requests and expressing her needs. In turn, the shy behavior of Deborah, which was present in childhood, also remained in adolescence, in the difficulty of starting conversations. Thus, the social skill class of communication and assertiveness presented difficulties since childhood and can be related to the academic performance, as Deborah and Rita stopped studying. In this sense, a longitudinal study showed a two-way effect between academic performance and social skills (Caemmerer & Keith, 2015).

The maintenance of interpersonal difficulties identified in the three cases can be understood by the lack of new learning experiences, from peers, family members or specific interventions, such as Social Skills Training. In the case of Rita, by keeping her feelings to herself, without having a support network in adolescence, there were impediments in the exercise of other social skill classes, considering that the social support from colleagues, parents and teachers mainly contributes to the social skills of adolescent females, compared to adolescent males (Nilsen, Karevold, Røysamb, Gustavson, & Mathiesen, 2013). In the three cases, interventions aimed at developing social skills could have been carried out during adolescence in schools, given the importance of the social role that the school plays in the life of adolescents (Andretta, Limberger, & Oliveira, 2014).

Both Isabel and Deborah had little contact with peers in adolescence. In this stage, the lack of contact with peers and social relationships that provide little social contact, imply greater probability of behavioral and emotional difficulties, such as drug use (Leme, Fernandes, Jovarini, & Achkar, 2015). From this perspective, adolecents who have not developed the ability to interact socially in a satisfactory manner may be rejected by their peers and use psychoactive substances as a maladaptive way to deal with their difficulties (Wagner & Oliveira, 2015). A study performed in Estonia with 2,460 students, aged between 15 and 16 years, found that adolescents who had low social skills had greater chances of using tobacco, cannabis, sedatives and inhalants (Vorobjov et al., 2014). In the cases of Deborah and Rita, the use of tobacco and marijuana were also reported in adolescence, as will be presented in the following axis.

In the drug use axis, it was observed that in childhood and adolescence, in all three cases, the women saw family members using drugs problematically, often as a way to escape their day to day problems, therefore, being exposed to an inadequate model of problem solving (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014). In this sense, it is clear that young people tend to replay the inappropriate behavior they learn during their childhood and adolescence, and their family members appear as the main models, which are configured as maladaptive responses to day to day interventions (Botvin & Griffin, 2015). It should be noted that, regarding the crack use, in the three cases it was people who were close that offered them the drug. Furthermore, Isabel reported that when she saw her boyfriend using crack, she wanted to "share" that moment with him. Thus, beyond dependence, the drug ends up having a role of articulation in relationships, making it more difficult to exit from this vicious circle, as in the case of Isabel.

In the adult life axis, for Isabel and Deborah similarities were found with their older children. In the case of Isabel's daughter, the difficulty in asking for information, and in the case of Deborah, the shyness of her son, confirm the data that learning skill classes also has an intergenerational relationship (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2013). Furthermore, the fact that Isabel continued to make the requests for her daughter, causes this ability to remain less developed in her daughter, reinforcing this behavior. Thus, the importance of the social skills of mothers in their management with their children can be perceived. The convergence between positive maternal practices and the social skills of the children was found in a Brazilian study with 24 mothers and their adolescent children (Sabbag & Bolsoni-Silva, 2015). The authors pointed out that when mothers value the interest of adolescents, they participate in an active way to express their opinions in the interactions.

Only Isabel perceived an evolution in her social skills, which was linked to the entry into the technical course and then the graduation program. It is comprehended that social skills can increase with schooling due to the contexts of interaction provided and the positive experiences perceived (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2014). Deborah, in turn, had not completed High School Education and referred to social isolation. With the gap between users and non-users it was even more difficult for the participants to develop their social skills so that they could contribute to their well-being, thus improving their deficits or working toward a new behavioral repertoire being acquired. For example, the ability of having resourcefulness in a social context so that they can acquire new friends outside of the environment where there is drug use. In this sense, low education simultaneously leads to more stressful situations and a lack of resources, according to a Dutch study of 3,050 participants (Mulder, Bruin, Schreurs, Ameijden, & Woerkum, 2011). The authors suggest Social Skill Training as a strategic tool for much of the population, especially those with low education.

Finally, the three cases share difficulties in interpersonal relationships during the treatment. Therefore, when the deficits in social skills persist, treatment may be less useful, due to lack of resources in that situation or due to the work that happens in the intervention often being focused on the deficits of the participants and not on the resources. Thus, someone who presents aggressiveness can find it easy to communicate with strangers, and this resource can be worked with when identified in the social skills instruments available. The need for focused interventions aimed at increasing the social skills of female crack users is therefore emphasized, especially skills that relate to self-control, denial and establishing links with people outside the drug use environment (Andretta et al., 2016). With this, there will be contributions to satisfactory interactions between professionals and patients, as well as between the patients themselves, so that they feel more willing to participate in therapeutic groups and feel free to make requests and express their doubts about the treatment.

Final Considerations

Comprehending the cases revealed the importance of social skills throughout the life cycle and in the context of drug use. The participants reported difficulties in their social skills since childhood, because of their personal characteristics and lack of contexts that would allow the development of a socially skilled repertoire. Thus, preventive interventions should emphasize the critical moments of the development, in order to avoid risk behaviors such as drug use.

The three cases presented difficulties in the use of social skills that could be developed from interventions, such as Social Skills Training, improving social interactions, including those in the context of the treatment of drug use. By analyzing the social skills inventory and from the interview, a deeper understanding of this phenomenon was possible. Thus, it was observed that the clinical interview allowed the analysis of the social skills of female crack users throughout the life cycle, identifying difficulties and resources of the participants. It should be noted that the social skills that each participant expressed more easily, such as cordiality, could be the first skills to be worked with in an intervention, in order to promote the motivation for carrying out other activities. Thus, further studies using this interview are needed, in order to obtain information relevant to the comprehension of the case and for planning interventions.

The limitations of the study were related to the use of self-report instruments. It is suggested that future studies contemplate the observation of the behavior in different interaction contexts, considering the classes of responses (assertive, aggressive and passive) in the evaluation. Furthermore, it is also suggested that psychiatric comorbidities are considered in the planning of the Social Skills Training, by assessing the intensity of the symptoms during the intervention.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Manual diagnóstico e estatístico dos transtornos mentais. DSM IV-TR (4. ed.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais. DSM-5. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Amorim, P. (2000). Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): Validação de entrevista breve para diagnóstico de transtornos mentais. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 22(3),106-115. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462000000300003 [ Links ]

Andretta, I., Limberger, J., & Oliveira, M. S. (2014). Abandono de tratamento de adolescentes com uso abusivo de substâncias que cometeram ato infracional. Aletheia, 43(44),116-128. Recuperado em http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=115039411009 [ Links ]

Andretta, I., Limberger, J., & Schneider, J. A. (2016). Social skills in crack users: Differences between men and women. Psicologia Reflexão e Crítica, 29(45),1-8. doi: 10.1186/s41155-016-0054-4 [ Links ]

Angélico, A. P., Crippa, J. A. S., & Loureiro, S. R. (2006). Fobia social e habilidades sociais: Uma revisão da literatura. Interação em Psicologia, 10(1),113-125. Recuperado em http://revistas.ufpr.br/psicologia/article/viewFile/5738/4175 [ Links ]

Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. (2015). Critérios de Classificação Econômica Brasil. Recuperado em http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil [ Links ]

Botvin, G. J., & Griffin, K. W. (2015). Treinamento de habilidades para a vida. In S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-Grança, & K. B. Santos (Eds.), Prevenção e promoção em Saúde Mental: Fundamentos, planejamento e estratégias de intervenção (pp. 405-418). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopys. [ Links ]

Caemmerer, J. M., & Keith, T. Z. (2015). Longitudinal, reciprocal effects of social skills and achievement from kindergarten to eighth grade. Journal of School Psychology, 53,265-281. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.05.001 [ Links ]

Cunha, J. A. (1993). Psicodiagnóstico-R (4. ed.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2001). Inventário de Habilidades Sociais: Manual de aplicação, apuração e interpretação. São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2013). Social Skills Inventory (SSI-Del-Prette): Characteristics and studies in Brazil. In F. L. Osório (Ed.), Social anxiety disorders: From theory to practice (pp. 49-62). New York: Nova Science. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2014). Psicologia das relações interpessoais: Vivências para o trabalho em grupo. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., Ferreira, B. C., Dias, T. P., & Del Prette, A. (2015). Habilidades sociais ao longo do desenvolvimento: Perspectivas de intervenção em saúde mental. In S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-Grança, & K. B. Santos (Eds.), Prevenção e promoção em Saúde Mental: Fundamentos, planejamento e estratégias de intervenção (pp. 318-340). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopys. [ Links ]

Feldens, A. C. M., Silva, J. G. D., & Oliveira, M. D. S. (2011). Avaliação das funções executivas em alcoolistas. Cadernos de Saúde Coletiva, 19,164-171. Recuperado em http://www.cadernos.iesc.ufrj.br/cadernos/images/csc/2011_2/artigos/csc_v19n2_164-171.pdf [ Links ]

Feitosa, F. B. (2013). Habilidades Sociais e sofrimento psicológico. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 65(1),38-50. [ Links ]

Fernandes, C. S., Falcone, E. M. O., & Sardinha, A. (2012). Deficiências em habilidades sociais na depressão: Estudo comparativo. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 14(1). Recuperado em http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-36872012000100014&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1997). Entrevista estruturada para transtornos de personalidade do DSM-IV, SCID-II (1,0): Versão brasileira (N. M. M. Melo & B. P. Rangé, Trads.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ. [ Links ]

Jansson, L. (1984). Social skills training for unipolar depression: A case study. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 13(4),237-241. doi: 10.1080/16506078409455717 [ Links ]

Leme, V. B. R., Fernandes, L. M., Jovarini, N. V., & Achkar, A. M. (2015). Relações interpessoais e habilidades sociais de adolescentes de contextos sociais vulneráveis. In Z. A. P. Del Prette, A. B. Soares, C. S. Pereira-Guizo, M. F. Wagner, & V. B. R. Leme, Habilidades sociais: Diálogos e intercâmbios sobre pesquisa e prática (pp. 103-127). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopsys. [ Links ]

Limberger, J., & Andretta, I. (2015). A compreensão das habilidades sociais a partir do ciclo vital. In Z. A. P. Del Prette, Anais do V Seminário Internacional de Habilidades Socias. Pirenópolis, GO, Brasil. [ Links ]

Limberger, J., & Andretta, I. (no prelo). Associações entre habilidades sociais e comorbidades psiquiátricas de mulheres usuárias de crack. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia. [ Links ]

Limberger, J. (2016). Mulheres em tratamento pelo uso do crack: Habilidades socias e características clínicas (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, RS, Brasil). doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1575.8326 [ Links ]

Melo, N. M. M., & Rangé, B. P. (Trads.). (2008). Entrevista estruturada para transtornos de personalidade do DSM-IV, SCID-II (1,0): Versão brasileira. Rio de Janeiro, RJ. [ Links ]

Mulder, B. C., Bruin, M., Schreurs, H., Ameijden, E. J. C., & Woerkum, C. M. J. (2011). Stressors and resources mediate the association of socioeconomic position with health behaviours. BMC Public Health, 11(789),1-10. doi: 10.1186/14712458-11-798 [ Links ]

Nascimento, E. (2004). Adaptação e padronização brasileira da Escala de Inteligência Wechsler para Adultos. Porto Alegre, RS: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Nilsen, W., Karevold, E., Røysamb, E., Gustavson, K., & Mathiesen, K. S. (2013). Social skills and depressive symptoms across adolescence: Social support as a mediator in girls versus boys. Journal of Adolescence, 36,11-20. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.08.005 [ Links ]

Sabbag, G. M., & Bolsoni-Silva, A. T. (2015). Relações entre práticas educativas e as habilidades sociais educativas de mãe de adolescentes. In Z. A. P. Del Prette, A. B. Soares, C. S. Pereira-Guizo, M. F. Wagner, & V. B. R. Leme, Habilidades sociais: Diálogos e intercâmbios sobre pesquisa e prática (pp. 103-127). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopsys. [ Links ]

Schneider, J. A., Limberger, J., & Andretta, I. (2016). Habilidades sociais e drogas: Revisão sistemática da produção científica nacional e internacional. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 34(2),339-350. doi: 10.12804/apl34.2.2016.08 [ Links ]

Segrin, C. (2010). Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(3),379-403. [ Links ]

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., ...Dunbar G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal Clinic Psychiatry, 59(Suppl. 20),22-33. [ Links ]

Sintra, C. I. F., Lopes, P., & Formiga, N. (2011). Condutas antissociais e delitivas e habilidades sociais em contexto forense. Psicologia Argumento, 29,383-399. [ Links ]

Terroso, L. B., Pedroso, F. N., & Kurle, A. M. (2015). Habilidades sociais na adolescência: Conceituação, avaliação e intervenção. In I. I. L. Argimon, C. S. Esteves, & G. W. Wendt (Eds.), Ciclo vital: Perspectivas contemporâneas em avaliação e intervenção. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora Universitária da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. [ Links ]

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6),349-357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [ Links ]

Vorobjov, S., Saat, H., & Kull, M. (2014). Social skills and their relationship to drug use among 15-16-year-old students in Estonia: An analysis based on the ESPAD data. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 31. Recuperado em http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/nsad [ Links ]

Wagner, M. F., & Oliveira, M. S. (2015). Habilidades sociais no abuso e na dependência de maconha. In Z. A. P. Del Prette, A. B. Soares, C. S. Pereira-Guizo, M. F. Wagner, & V. B. R. Leme, Habilidades sociais: Diálogos e intercâmbios sobre pesquisa e prática. Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopys. [ Links ]

Wechsler, D. (1997). Weschsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2010). Estudo de caso: Planejamento e métodos. Porto Alegre, RS: Bookman. [ Links ]

Received: 22/02/2016 Article derived from dissertation: "Women in treatment for the use of crack: social skills and clinical characteristics", authored by the first author, with the guidance of the second author, defended in january 2016, in the Graduate Program in Psychology - Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS). Scholarship Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) /Programa de Suporte à Pós-Graduação de Instituições de Ensino Particulares (PROSUP). Agradecemos a CAPES pela bolsa CAPES/PROSUP de Mestrado da primeira autora. Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Jéssica Limberger

Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Escola de Saúde, Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia

Avenida Unisinos, 950, Bairro Cristo Rei

São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil 93020-000

E-mail: jessica.limberger.psi@gmail.com

1st revision: 15/08/2016

Accepted: 1º/09/2016

texto en

texto en