Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.26 no.2 Ribeirão Preto abr./jun. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.2-14Pt

ARTICLE

Conceptions of mental health professionals about the therapeutic activity in the CAPS

Teresinha Cid ConstantinidisI; Maria Fernanda Barboza CidII; Lenise Moraes SantanaIII; Suzana Rodrigues RenóIV

IUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil. Orcid.org/0000-0001-9712-3362

IIUniversidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasil. Orcid.org/0000-0002-0199-0670

IIIUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil. Orcid.org/0000-0002-0169-3828

IVUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil. Orcid.org/0000-0002-3279-092X

ABSTRACT

This is a qualitative research of exploratory design on the conceptions of mental health professionals about the use of therapeutic activities in their practices in psychosocial care centers (CAPS). Understanding the knowledge that subjects the use of therapeutic activity is of paramount importance in the evaluation of services and in the construction of new models of mental health. Three focal groups were held with professionals from three CAPS cities in the southeast region of the country. The analysis of the data was done through content analysis of thematic modality. The articulated analysis with the theoretical reference concerning the paradigm of the practices in mental health pointed out that the professionals recognize the activities carried out in a decentred clinic of the symptom and the medicalization of the mental disorder, as a form of reception, centered in the therapeutic process, but with few mentions Concrete actions in the territory and community integration of people with mental disorders.

Keywords: Therapeutic activity, deinstitutionalization, care production in mental health.

Psychiatric reform, which involved the transformation of the care provided to individuals under severe mental suffering, allowed for advances in how the experience of suffering is understood and, in particular, in the development of new strategies for the care of this population. Among such advances, the use of activities as a part of the therapeutic process underwent changes, accompanied by the formulation of new clinical, institutional, and social approaches to mental suffering. Under the current view, the aim of the performance of activities by the affected population is to oppose segregation and to favour learning and social participation. Thus, it differs from the approach followed before the reform, which, given that it originated in moral treatment and was grounded in hospital-based control of the time and minds of inpatients, advocated the performance of such activities as a tool for them to attain socially accepted roles (Amarante, 2014).

Mainly influenced by the Italian deinstitutionalisation movement, the process that came to be known as the "Brazilian Psychiatric Reform" culminated in 2001, when Law No. 10.216 (i.e., the "Psychiatric Reform Law"), was passed. This movement posits psychosocial rehabilitation as a new model for mental health care. Its overall goal is to facilitate the restructuration of autonomy and to help individuals under mental suffering achieve greater social participation in the community. Social participation means the achievement of the status of political subject by the mentally ill, a process that includes what came to be known as the subject's protagonism (Torre & Amarante, 2001). Such protagonism involves the active participation of the subjects and their political participation in debates on their treatment. A protagonist leaves the role of patient, of the alienated individual, of someone needing a guardian, to become an autonomous, active participant who makes decisions about/addresses his/her social environment. As a result, psychosocial rehabilitation introduces a perspective of intervention that breaks with traditional psychotherapies, which target the isolated individual, to focus on the social subject, understood from a relational stance that considers his/her inclusion in the culture and social networks. To that end,

... it is necessary to adopt a humanised model of health that takes into account integral care and the active participation of all, particularly that of the affected individuals themselves in the design and execution of their own therapeutic processes, strengthening "social protagonism" to develop autonomy and self-determination. (Health Unic System, 2010, p. 63)

Rotelli (2001) calls attention to therapeutic work that focuses on the production of life, upon considering interventions aimed at the reconstruction of individuals admitted to institutions for being considered mentally ill, for the purpose of potentiating their role as social actors and hindering their nullification under the mask of disease. "Treatment should mean, here and now, efforts to transform the patients' way of living and feeling their suffering and, simultaneously, to transform their concrete everyday life" (p. 76).

Therapeutic activities are the main technologies of care applied at Psychosocial Care Centres (Centros de Atenção Psicossocial - CAPSs) in Brazil (Tavares, Barone, Ferenades, & Moniz, 2003). They seek the integration of the affected individuals and their relatives into society from a community-based perspective. The affective, social, family, and community relationships of individuals under mental suffering are the first priority of the actions performed at such services (Azevedo & Miranda, 2011).

In a study that is a part of the assessment of CAPSs in southern Brazil, Kantorski et al. (2011) identify the contributions of the therapeutic supports developed at such institutions. These authors observe that the availability of spaces that ensure the development of the subjects' potentialities is highly relevant for the social insertion of individuals under psychological suffering; thus, they suggest including the performance of activities as a part of the therapeutic plan. According to these authors, the activities developed at the CAPSs may help the targeted population conquer or re-conquer their everyday life and develop job skills, independence, freedom, and autonomy. One of the spaces available for the performance of activities at such substitutive services is the therapeutic workshop:

Such workshops consist of group activities in the presence and under the supervision of one or more professionals, monitors, and/or interns. Activities are selected based on the participants' interests, the service technicians' possibilities, and on needs, and they aim at a greater social and family integration, the expression of feelings and problems, the development of body skills, the performance of productive activities, and the collective exercise of citizenship. (Ministry of Health, 2004)

According to Azevedo and Miranda (2011), the workshops point to the intertwining of subjectivity and citizenship (i.e., of the mental and political dimensions of subjects). They may be considered therapeutic when they afford room for speech, expression, and receptivity, and they may favour the process of social insertion of individuals. It is worth stressing that therapeutic activities are included in various modalities of mental health care; that is, they are not restricted to therapeutic workshops. Therapeutic activities may be performed in individual consultations, therapeutic groups conducted under various approaches (occupational therapy groups, psychodrama, etc.) and therapeutic accompaniment (TA) actions, among others. However, according to Brazilian studies, at mental health care services, therapeutic activities are mainly performed within the therapeutic workshop setting (Azevedo & Miranda, 2011; Soares & Reinaldo, 2010).

Brazilian studies consider workshops a group-based device within the process of care delivery (Benevides, Pinto, Cavalcante, & Jorge, 2010; Jucá, Medrado, Safira, Gomes, & Nascimento, 2010), a successful clinical-political instrument in the process of deinstitutionalisation of mental illness (Oliveira & Passos, 2007; Pádua & Salum, 2010).

In addition, studies such as that by Lussi and Shiramizo (2013) approach therapeutic workshops as a resource for the production and exchange of goods and affects via workshops for job and income creation. In the current mental health policy, this type of workshop is considered part of the implementation of the Psychosocial Care Network (Rede de Atenção Psicossocial - RAPS; Portaria n. 3.088, 2011), which recommends a wider availability of such workshops and intersectoral strategies for income creation, such as social cooperatives. Therefore, the workshops do not merely serve as a therapeutic instrument but, rather, extend beyond institutional boundaries to reach the territory. The international literature includes studies in which therapeutic activities are performed outside the context of groups, such as rehabilitation activities performed in the community to train skills related to activities of daily living and social interaction (Saraceno, 2007; Test & Stein, 2000). Therefore, independent of their methods, Brazilian and international studies approach therapeutic activities as a possibility for inventing new ways of life and new ways to address eventual situations, symptoms, disease, and relationships. Nevertheless, together with the emphasis on the relevance and psychosocial scope of therapeutic activities, practically all of the studies also include critical reflections on the work currently being performed by mental health professionals with regard to these devices to avoid falling into the pitfalls of segregationist psychiatry.

Psychiatric institutions operate based on the rationalist paradigm of modern science; they attribute particular value to the problem-solution relationship, through which diagnosis is bounded to prognosis and which leads from disease to cure (Rotelli, 2001). Because deinstitutionalisation is the practical work of transforming how individuals are treated, the solution-cure is no longer the target in the case of individuals under mental suffering, being replaced by a complex and daily set of strategies that perform the shift from cure to the production of life. In this process of care, individuals are considered protagonists. Within this context, the performance of activities is a part of a project to achieve the emancipation of subjects; it does not seek to remove symptoms and/or eliminate crises (understood in the medical sense) but, rather, represents a strategy for endowing individuals with protagonism while respecting their singularity (Constantinidis & Cunha, 2016).

Lima (2004) discusses the difference between contemporary practices of the performance of activities in the mental health field and moral treatment. According to her, although practices including activities are a legacy of moral treatment, an inversion of direction is needed: they must be problematised so that they do not become naturalised. This is the condition noted by Lima to undo "such naturalisation, which often has as an effect the maintenance of alienating logics disguised as innovations and the weakening of the disruptive and inventive power of activities" (Lima, 2004, p. 32).

Along the same lines, Bezerra (2007) observes that fighting against the fading of policies and the increasing hegemony of technical discourse does not merely mean having an understanding of and putting into practice the suggested policies and models. According to this author, it means that professionals must combat "mental madhouses" (Pelbart, 1991), which are resistant to change because they are rooted in deeply internalised cognitive and affective patterns.

In this regard, the study by Fiorati and Saeki (2012) indicates that the advances in this field notwithstanding, the work of some mental health professionals remains characterised by the extreme technification of therapeutic actions that emphasise clinical-pharmacological treatment. As a result, psychosocial actions fade into the background, work at services is interrupted, and the targeted individuals do not achieve social inclusion. According to these authors, changes in the asylum infrastructure - such as the introduction of group work and various therapeutic workshops - and in the legislation on psychiatry/mental health did not suffice. Azevedo and Miranda (2011) consider that commitment by men-tal health professionals is needed for changes in the logic of psychiatrisation and in how care is provided to occur so that they become community-based. These authors observe that engagement is needed for the development of new relationships between services and the community, including the creation of social networks for supporting individuals and territory-based services so that the community may play an instrumental role with regard to alternative responses to mental suffering. To that end, the scope of therapeutic activities must expand beyond the boundaries and physical space of institutions to reach the community and the existential territory of individuals.

Facing this scenario, a reflection on the place of the mental health care practice and the knowledge that subjectifies it and grounds the possibility of action of mental health professionals is of paramount importance because how this practice actually occurs involves representations that ground the use of therapeutic activities.

The present study aims to advance such reflections, seeking to promote the emergence of new elements based on mental health professionals' understanding of the performance of therapeutic activities in their everyday practice at substitutive mental health services. These types of studies are important because they contribute to a more thorough understanding of psychosocial care practice by raising new questions to be investigated in future studies and by providing grounds for the planning and implementation of more effective practices in mental health care.

Therefore, the objective of the present study is to understand the conceptions of mental health professionals regarding the use of therapeutic activities in their practice at CAPSs.

Methods

Based on the aim of understanding the meanings that mental health professionals attribute to therapeutic activities in mental health care practice, the qualitative method is the most adequate.

Participants

The study sample was composed of 21 mental health professionals who provide care at three CAPSs in a large city in south-eastern Brazil. Two services were CAPS III, and one was a CAPS i II.

Based on the study aims, the use of therapeutic activities in the professionals' practice was the single criterion for participant selection. Two social workers, two art therapists, two nurses, one physician, three music therapists, six psychologists, and five occupational therapists met the inclusion criterion and agreed to participate in the study. Mental health professionals who reported that they did not uses therapeutic activities in their practice were excluded.

Length of work in mental health care was not considered a criterion for participant selection, but it varied from three to 20 years. Therefore, the professionals' experience in mental health care was highly variable, which was considered a favourable situation for the aims of this study.

Instrument

For data collection, an instrument likely to stimulate the participants' reflections on the use of therapeutic activities in their practice as well as the expression of their representations and perceptions on the subject was sought. The method that proved to be most adequate to collect the desired data was the focus group, which is based on the interaction among participants relative to the topics presented for discussion. This instrument is grounded in the human tendency to form opinions and adopt attitudes when interacting with other individuals. The combined work of the participants of focus groups in the elaboration of the topics presented results in more information and a greater wealth of detail than the mere sum of individual responses (Dias, 2000).

Data Collection Procedures

CAPSs were selected as the setting because they represent a strategic device in mental health care (i.e., an open and community-based health service that provides daily care to individuals with severe and persistent mental disorders, including clinical monitoring and social reinsertion; Ministry of Health, 2004). Activities are one of the care strategies deployed at CAPSs because they seem to be valuable resources for psychosocial rehabilitation (Kantorski et al., 2011; Lima, 2004).

First the investigators presented the project and its goals to the professionals at the three participating CAPSs in staff meetings; on this occasion, the study was discussed, and any questions were answered. Next, according to the participants' schedule, the dates and times for the focus groups were established.

One single focus group consisting of one single session was conducted at each CAPS, with average duration of 90 minutes. Therefore, a total of three focus groups were conducted, with an average of seven participants per group. The sessions were moderated by two investigators with previous training in this technique. The topics that oriented discussions in the focus groups were daily work at the CAPSs; the relationship established by the professionals with the activity/occupation in their mental health care practice; and the advantages and disadvantages of using therapeutic activities in mental health actions. The sessions were recorded as digital audio files, which were subsequently transcribed and analysed.

Data Analysis Procedures

The collected material was treated and coded according to Bardin's content analysis method (1979). The overall goal was to discuss/interpret the data gathered in the focus groups; the aforementioned procedure for treatment/analysis was selected because it allows discussions/inferences of the data analysed. The present study adopted the thematic analysis modality, "which seeks, in verbal or textual expressions, recurrent general themes that appear within various more concrete contents" (Turato, 2008, p. 442).

The investigators transcribed the data gathered in the focus groups, and this step was a part of the first reading of the material. It was followed by several other readings to "ruminate on the data", to allow oneself to "be invaded by impressions and orientations" (Bardin, 1979, p. 40). Based on the information provided by the results, analysis was performed according to the framework corresponding to the paradigm for mental health practices, more specifically, deinstitutionalisation.

Ethical Procedures

Considering the investigated population, the National Health Council guidelines and standards for research with human beings were complied with during data collection. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo - UFES), ruling no. 4821/2009.

To protect the participants' anonymity in the transcriptions of excerpts presented in the Results section, their names are replaced by the letter P followed by an identification number.

Results and Discussion

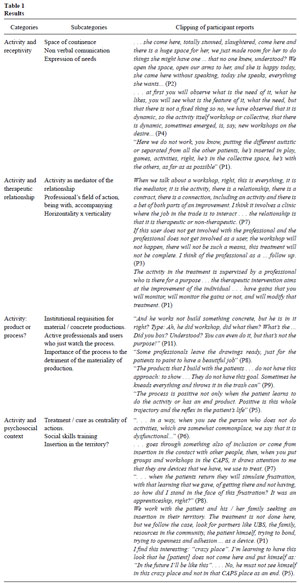

The analysed data exhibited discursive regularities defining four thematic categories: (a) activity and receptivity; (b) activity and the therapeutic relationship; (c) activity: product or process; and (d) activity and the psychosocial context. These categories are described in the following table.

Results

Activity and Receptivity

According to Teixeira (2001), receptivity is a conversational technique in which the needs of subjects are identified together with the possibilities of satisfying them. This author suggests an encounter between the professional and the service user within an approach to practice conceived of as "receptivity-dialogue", a "conversational technique". Londero (2010) stresses the impossibility of a single model for receptivity. According to Schmidt and Figueiredo (2009), receptivity consists of a process that depends on the clinical resources of the staff, listening, assessment, and distinguishing demands. Scheibel and Hecker Ferreira (2012) emphasise that receptivity is not restricted to the traditional notion of triage.

The participants observed that receptivity begins at the arrival of users to services, with the aim of organising the demand, and that it also permeates and is transverse to the therapeutic process.

"... first, you try to observe what his needs are, what he likes, what his characteristics are, what [his] needs are, but this is not fixed, we've noticed it's dynamic" (P4).

Pinho, Hernández, and Kantorski (2010) stress that receptivity is transformed at the beginning, middle, and end of any health care process when it is raised to the category of social responsibility for the problems of another individual, as a mechanism for simultaneously listening and offering possibilities. In this regard, we observed that the notion of receptivity reported by the participants is in line with that described in the cited studies. However, the results indicate that the dialogue with service users, conversation, which is typical of the receptivity process, goes beyond verbal communication, which represents an advancement relative to the model of receptivity discussed up to this point.

Through observation, the participants seek to identify the service users' needs well beyond their explicit demands within the dynamics of the therapeutic activities performed at the CAPSs. This process involves negotiation, even when implicit, between the actual possibilities that professionals/services can offer and the service users' demands. Receptivity is actualised through therapeutic activities, in which new elements may appear and the difference represented by madness may manifest and be received. According to the participants, therapeutic activities at the CAPSs contribute to the receptivity of service users with all their pain and to the development of other relational possibilities:

... she comes here fully stunned, in a catastrophic state, she comes here, and there's a huge space for her, we just made room for her to do things that perhaps she'd have a... which no one ever knew about, understand? We made room, we opened our arms to her, and now she's utterly happy. When she first came here, she didn't speak. Now, she talks as much as she wants... (P2)

The space afforded at the CAPSs for ther apeutic activities is characterised by its ability to contain the various manifestations of service users, as the following excerpt corresponding to P15 shows:

Here, we don't work by distinguishing or separating an autistic individual from all other patients. He participates in the fun and games, in the activities, he's in the collective space, together with the others, as much as possible, as a function of his possibilities. (P15)

In this regard, we may infer that in such spaces, receptivity for the performance of activities, in addition to being a strategy for inclusion, as shown by the participants' narratives, also contributes to the development of citizenship among individuals under mental suffering, which is the very goal of deinstitutionalisation. It thus represents the advancement of this process within the micro-political field, the CAPSs and the workshops (i.e., the collective spaces where individuals perform group or individualised activities established according to the therapeutic plan specifically designed for each service user).

Future studies focusing on the impact and assessment of therapeutic activities as a strategy used by mental health professional in their listening and receptivity of the service users' demands from the perspective of the various actors (service users, their relatives, professionals) would be interesting. The reason is that such studies would contribute to a broader understanding of the dynamics of care adopted at the CAPSs and the effects that it has on the lives of the service users.

Activity and the Therapeutic Relationship

According to the narratives gathered in the focus groups, therapeutic activities are the locus where the encounter between the service user, the activity, and the professional occurs. The participants stated that the activity performed in the various CAPS actions mediates the relationship between the service user and the professional, which may become therapeutic or not, as shown by P7's and P3's narratives:

When we talk about the workshops, all of it is the individual, it is the mediator, it is the activity, there's a relationship, there's a contract, there's a link, even when entering an activity, and both sides are betting on some improvement. I believe it's a matter of [a type of] clinical practice where [our] task is to interact . . . the relationship is what is therapeutic or is not therapeutic. (P7)

"If the service user doesn't become involved with the professional and the professional doesn't become involved with the service user, the workshop won't happen. This means it won't exist, treatment won't be complete" (P3).

Therefore, the relationship between the service user and the professional, including the contract that they establish and their betting on the improvement of mental suffering, is in the foreground of treatment. Activities facilitate this process. Therefore, the relationship is what is therapeutic, not the activities themselves. This finding agrees with the view of Csordas (2008), according to whom the emphasis falls on the relationship that is established rather than on the activities themselves. Thus, the mere performance of activities does not guarantee that care/treatment will occur. A triadic relationship is necessary: the service user - the activity - the therapist.

The participants disagreed as to the place of professionals in the therapeutic relationship and the performance of activities. For some of them, professionals become involved in and accompany the actions of service users at CAPS events, as illustrated by the following narrative:

I bring the trigger ... and all of a sudden, I'm [just] accompanying, and I realise that the direction of things changes, obviously there's an axis, but the direction changed because two or three are demonstrating, [they] are bringing elements that make the activity become rearranged. (P9)

To other participants, professionals have the role of supervisors (i.e., of individuals who act through activities according to pre-determined circumstances, as the following narratives show):

Activities, during treatment, are supervised by the professional who's there with some goal . . . the therapeutic intervention seeks the improvement of individuals . . . gains that you'll monitor, you'll follow up the gains or not, and you'll keep modifying the treatment. (P1)

"Professionals are there at workshops, working with therapeutic activities during treatment ... with a goal. Treatment has a goal, an expected result that I'll manage and make occur" (P12).

The notion of professionals who become involved and accompany brings an additional component to the definition of workshop provided by the Health Ministry, which states: "These workshops are group activities performed in the presence and with the orientation [our emphasis] of one or more professionals, monitors, and/or interns" (Ministry of Health, 2004). According to this definition, the professionals' participation is restricted to presence and orientation, and no mention is made of the professionals' involvement in this process. To accompany is to keep company, to walk in company, to participate, according to each professional, to be with the service users in the workshops, constituting the horizontal nature of the relationship upon undoing the constitutive asymmetry of the initial relationship between the individual who seeks help and the professional who has knowledge about the other and who provides care (Constantinidis, 2011). According to Inojosa (2005), the current mental health policy seeks to retrieve "a solidary relationship among subjects, a conscious effort to work with the asymmetries, by respecting the other's knowledge and power" (p. 6).

Nevertheless, according to some participants, professionals supervise activities and operate based on a pre-set goal related to the "improvement" of the target-individual and that is a part of the latter's therapeutic process. This finding leads one to contemplate the verticality of the therapist-service user relationship, which has been discussed by several authors, such as Vasconcellos and Azevedo (2010), who call attention to the issue of the professionals' having "knowledge about", which leads to a situation in which professionals are in a place above that of service users. In this context, service users adopt a passive and consenting posture and attribute to professionals the decision-making power and the competence to say what is good for them. These authors further observed that this type of relationship was called into question by the psychiatric reform movement because the polarisation that it involves may hinder the constitution of an intersubjective and participative field for care (Vasconcellos & Azevedo, 2010).

It is important to note that according to this finding, it is not possible to characterise the reported therapist-service user relationship as vertical, and it was not the aim of the present study to explore in depth such relational dynamics. In addition, the fact that professionals plan their actions as a function of pre-set goals may not necessarily indicate that service users are passive in this process. Therefore, further studies that address the dynamics of the therapist-service user relationship at mental health services from the perspective of the psychiatric reform movement and considering the complexity of the experience of mental suffering are important to achieve a more thorough understanding of how mental health professionals perform their work and establish relationships in the management of care.

Activity: Product or Process?

The participants emphasised the therapeutic process that occurs in the performance of activities and expressed concerns as to how to characterise the final product of workshops: "Some professionals provide ready-made drawings for the patients to paint and thus obtain a beauti-ful product" (P8). In this regard, Delvano (2015) observes that in their search for a final product with social value, some professionals take the initiative to perform any type of activity, leaving for service users the role of spectators or consumers of suggestions.

Oliver, Tissi, Aoki, Vargem, and Ferreira (2002) observe that the value attributed to the final product - its aesthetics, quality, usefulness - is owing the demands imposed by the consumer market. According to Kuntz (2016), consumption is intrinsically linked to sociability, integration, and belonging. In contrast to Delvano's (2015) observation, the participants of the present study did not consider the potentiality of the final product of activities; focusing on the process, they stressed that the idea behind the workshops is to construct something independent of production as a method of displaying skills or for commercial purposes:

"The products I make with patients ... do not have that focus: to show off ... That's not their goal. Sometimes, they crumple everything up and throw it in the trash" (P9).

"Sometimes, one expects a product that might be displayed. But there aren't any because what matters is the process the individual is undergoing rather than... the final thing" (P12).

And he works, not in constructing anything concrete, but it's he in himself. Like: Ah, he was in the workshop, then what did he do? What's the... Did he make a little box? Understand? He may even make one, but that's not the goal. (P11)

The professionals do not merely look for concrete products made by the service users; rather, they look for that which is produced "in between" the beginning - the entry of the individual into the activity, the elaboration of some material thing - and the final result of the explicit goal of the workshops. This "in between" includes doing, experimentation, interactions, the conquest of the new, and the possibility of creating new ways of being in the world. In addition, the narrative of P5 points to the relevance of the process when it has repercussions for the life and the concrete reality of individuals:

"The process is not only positive when the patient learns how to perform the activity or obtains a final product. The full trajectory is positive, in addition to its reflection on the patient's life" (P5).

The narratives point to the central position of process at the expense of product. However, Guerra (2004) observes that we cannot omit the fact that the reference of workshops is always a final product, the "materiality of products", as a function of their explicit nature: painting workshops, newsletter workshops, cooking workshops, and so forth. Workshops allow for the grasping of the new, for the expression of singularities, for the inscription of the difference proper to madness in culture and everything deriving therefrom because they are grounded in working with concrete things. Their subjective and socialising effects are grounded in the very concreteness of the materials and in the production of something. In addition, although consumption is not the only motive that constitutes social life, the inclusion of these experiences in the market (production and distribution) may promote exchanges of a different order, as Oliver et al. (2002) argue.

Therefore, on one hand, the participants demonstrated the priority given to one aspect of doing (i.e., the separation and opposition between the product and the process in relation to the performance of activities, being particularly concerned with attributing value to the subjects and their peculiarities within their life context grounded in significant relationships that may originate in that process). On the other hand, they did not consider the social inscription derived from the product's value as a consumer good. According to Oliver et al. (2002), making the final product become a consumer good that is likely to result in income creation demands instruments that are still poorly sedimented in the health care professionals' practice.

Activity and the Psychosocial Context

Despite the interest of psychosocial care in restructuring the care provided to individuals under mental suffering by focusing on the suffering individual rather than on deviations from a classificatory pattern, in the present study, we found narratives that classify behaviours in relation to the performance of activities according to a standard functioning:

"... in a way, whenever we see that someone does not perform common activities, we say he/she is dysfunctional..." (P6).

The narrative of P6 illustrates the posture of some professionals for whom, despite being in favour of deinstitutionalisation, in practice, their actions are attached to the pattern of normality, resulting in the non-involvement of service users with what is offered to them as a flaw related to an alleged normality. Such a classification pattern is part of the paradigm underpinning psychiatric institutions (Rotelli, 2001). The lack of coherence between the participants' discourse and practice brings out the "mental madhouses" (Pelbart, 1991).

For some professionals, the function of workshops is related to pedagogic processes, in which training emotional skills is possible. Such goals convey the idea of workshops as reproductions of micro-societies that are adequate for "simulations of processes" and teaching, having moral treatment as their implicit model.

"... when the patients come back, they'll simulate frustrations, thanks to the learning we offered, of getting there, but not questioning 'how did I arrive at this frustration?' It was something learned, right?" (P8).

This finding agrees with Lima's (2004) questioning of the naturalisation of practices and the presence of moral treatment behind innovative practices, which thus conserve the alienating logic of the old asylums and weaken the power that activities have. Similarly, therapeutic activities may be demarcated by methods and techniques that are proper to certain professional specialties, with a consequent loss of the dimension of a field of competence in mental health supported by the intersection of interdisciplinary practices.

... due to the professionals' interests, according to their personal and professional skills, in addition to the professional, he's trained in what? He works with what? Does he have skills and interest to work within his field or not? ... I believe that it's up to the professional to want to work within his field or not ... something specific, for instance, no one from the staff prescribes drugs, only the psychiatrists, who are not available for other interventions. (P19)

This finding agrees with the results of Fiorati and Saketi (2012) and Zerbetto, Efigênio, dos Santos, and Martins (2011), who point to the technification of therapeutic practices in mental health care, with the emphasis falling on clinical-pharmacological treatment, which pushes psychosocial actions to the background. A study by Galvanese, Nascimento, and DOliveira (2013) shows that the performance of therapeutic activities at CAPSs is associated with the conception of the "therapeutic activity myth" for reducing activities to medicine.

The results described up to this point indicate that the groups and therapeutic workshops conducted at CAPSs are viewed, on one hand, as a therapeutic device from the perspective of the inclusion of service users in their treatment; on the other hand, there is an awareness of the relevance of therapeutic activities, which, although performed at the institution, aim at the territory through actions targeting the family and the community.

We work with the patients and their relatives to develop insertion in their territory. Treatment is performed here [our emphasis], but we follow up the cases, look for partners such as BHUs [basic health units], the family, community resources, the patient him/herself, attempting to establish a link, attempting to establish an opening and adherence ... as a device. (P1)

The narrative of P1 points to a concern with territorial actions from a psychosocial perspective on care, which targets the subject as a whole. Despite the explicit intention to perform territorial actions noted by the participants in the present study, the results indicate a strictly clinical trend in the reported practice as performed within the CAPS. According to Onocko-Campos and Furtado (2006), the essential point is to preserve the links with the service users along the various stages of suffering. These authors observe that it is not a matter of negating or abolishing the clinical perspective but, rather, of broadening its scope by assuming responsibility for the concrete demands of service users. The issue under question is not to forego the clinical perspective in the care provided to individuals with mental disorders but, rather, to reassert the CAPS as a psychosocial care device for individuals with severe and/or persistent mental disorders by attributing value to the psychosocial trend that emphasises the transverse nature of clinical practice and territorial actions. As a result, territorial actions are not opposed to clinical actions.

Regarding the actions to be performed at the CAPSs, this finding agrees with the results obtained by Galvanese et al. (2013) in their study of the process of care via arts and culture conducted at CAPSs in the city of São Paulo. Out of 126 art and culture activities, 96 were performed within the CAPSs, which points to the professionals' trend to keep their actions within the institutions, making little use of urban and territorial spaces.

Constantinidis and Cunha (2016) emphasise how relevant it is for the activities performed inside or outside workshops to consider the territory, understood as the locus of action of the full service network and the citizens who belong to it. According to these authors, such an approach would allow for the articulation of services to reinvent life in all of its everyday aspects from which madness was expelled.

Final Considerations

Deinstitutionalisation does not merely mean an understanding of and putting into practice suggested policies and models; it is also the need for professionals to reflect on their daily practice of care for individuals with mental disorders. It is important for professionals to reflect on the ideological and theoretical-methodological assumptions that ground their practice to facilitate the changes needed for deinstitutionalisation. Without pretending to have exhausted the discussion on the subject of interest, we believe that the present study may contribute to such a reflection.

Regarding the use of activities in the care provided to individuals with mental disorders, the professionals recognise the activities performed at therapeutic workshops as a relevant device in their receptivity of individuals under mental suffering because they act as a catalyst in the therapeutic relationship within a clinical approach that does not have symptoms at its centre and that avoids the medicalisation of mental disorders.

According to the participants' narratives, the performance of activities inside the CAPSs still predominates, and few mentions of concrete actions in the territory were made. Within psychosocial rehabilitation, psychiatric care underwent a paradigm shift towards the affirmation of the service users' autonomy and the priority of the territory and everyday life in care-related actions. However, the participants of the present study did not emphasise the power of activities in mental health actions with the participation and integration in the community of individuals with mental disorders. Therefore, the relevance of studies that address the factors that enable, hinder, and/or impede the use of activities in the actions of mental health professionals in the territory (i.e., in the place where the life of individuals under mental suffering unfolds, is stressed).

Regarding the assessment of more effective mental health practices, the present study opens a discussion with a view to future studies on the impact of the various modalities of therapeutic activities on the lives of service users, particularly in relation to their experience of mental suffering and social participation, conducted from the perspective of service users and health care professionals.

References

Amarante, P. D. D. C. (2014). Saúde mental, desinstitucionalização e novas estratégias de cuidado. In S. Escorel, L. D. V. C. Lobato, J. C. D. Noronha, & A. I. D. Carvalho (Eds.), Políticas e sistema de saúde no Brasil (pp. 635-655). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. [ Links ]

Azevedo, D. M., & Miranda, F. A. N. M. (2011). Oficinas terapêuticas como instrumento de reabilitação psicossocial: Percepção de familiares. Escola Anna Nery, 15(2),339-345. doi: 10.1590/S1414-81452011000200017 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1979). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Benevides, D. S., Pinto, A. G. A., Cavalcante, C. M., & Jorge, M. S. B. (2010). Cuidado em saúde mental por meio de grupos terapêuticos de um hospital-dia: Perspectivas dos trabalhadores de saúde. Interface-Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, 14(32),127-138. Recuperado em http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pid=S1414-32832010000100011&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es [ Links ]

Bezerra, B., Jr. (2007). Desafios da reforma psiquiátrica no Brasil. Physis, 17(2). Recuperado em http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-73312007000200002&lng=en&nrm=iso [ Links ]

Constantinidis, T. C. (2011). Familiares de pessoas com sofrimento psíquico e profissionais de saúde mental: Encontros e desencontros (Tese de doutorado em Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil). Recuperado em http://repositorio.ufes.br/handle/10/3128 [ Links ]

Constantinidis, T. C., & Cunha, A. C. (2016). Desinstitucionalizando conceitos: A terapia ocupacional em busca de um (novo) lugar no cenário da saúde mental. In T. S. Matsukura & M. M. Salles (Eds.), Cotidiano, atividade humana e ocupação. Perspectivas da terapia ocupacional no campo da saúde mental (pp. 37-59). São Carlos, SP: Editora da Universidade Federal de São Carlos. [ Links ]

Csordas, T. (2008). Corpo/Significado/Cura. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. [ Links ]

Delvano, D. (2015). Artifícios, narrativas e bricolagens: Efetua(ações) na clínica do oficinar (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil). Recuperado em http://portais4.ufes.br/posgrad/teses/tese_9150_Daniel%20Delvano.pdf [ Links ]

Dias, C. A. (2000). Grupo focal: Técnica de coleta de dados em pesquisas qualitativas. Informação & Sociedade: Estudos, 10(2),67-72. Recuperado em http://bogliolo.eci.ufmg.br/downloads/DIAS%20Grupo%20Focal.pdf [ Links ]

Fiorati, R. C., & Saeki, T. (2012). As atividades terapêuticas em dois serviços extra-hospitalares de saúde mental: A inserção das ações psicossociais. Cadernos de Terapia Ocupacional UFS-Car, 20(2),207-215. doi: 10.4322/cto.2012.022 [ Links ]

Galvanese, A. T. C., Nascimento, A. de F., & DOliveira, A. F. P. L. (2013). Arte, cultura e cuidado nos centros de atenção psicossocial. Revista de Saúde Pública, 47(2),360-367. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047003487 [ Links ]

Guerra, A. M. C. (2004). Oficinas em saúde mental: Percurso de uma história, fundamentos de uma prática. In C. M. Costa & A. C. Figueiredo (Eds.), Oficinas terapêuticas em saúde mental: Sujeito, produção e cidadania (pp. 23-58). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Contra Capa. [ Links ]

Inojosa, R. M. (2005). Acolhimento: A qualificação do encontro entre profissionais de saúde e usuários. Trabalho apresentado no X Congreso Internacional del CLAD sobre la Reforma del Estado y de la Administración Pública (pp. 18-21). Santiago, Chile. Recuperado em http://bresserpereira.org.br/Documents/MARE/OS/inojosa_saude.pdf [ Links ]

Jucá, V. J. S., Medrado, A. C., Safira, L., Gomes, L. P. M., & Nascimento, V. G. (2010). Atuação psicológica e dispositivos grupais nos centros de atenção psicossocial. Mental (Barbacena), 8(14),93-113. Recuperado em http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1679-44272010000100006&lng=pt&nrm=iso [ Links ]

Kantorski, L. P., Coimbra, V. C. C., de Aquino Demarco, D., Eslabão, A. D., Nunes, C. K., & da Cruz Guedes, A. (2011). A importância das atividades de suporte terapêutico para o cuidado em um Centro de Atenção. Journal of Nursing and Health, 1(1)4-13. Recuperado em https://periodicos.ufpel.edu.br/ojs2/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/3401/2792 [ Links ]

Kuntz, F. M. R. (2016, 05-09 set.). O Consumo da Loucura: Um Ensaio Sobre a Loucura de Não Consumir. Trabalho apresentado no Intercom - Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação, XXXIX Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação. São Paulo, SP. Recuperado em http://portalintercom.org.br/anais/nacional2016/resumos/R11-0773-1.pdf [ Links ]

Lei No. 10.216, de 6 de abril de 2001. (2001, 09 abr.). Dispõe sobre a proteção e os direitos das pessoas portadoras de transtornos mentais e redireciona o modelo assistencial em saúde mental. Diário Oficial da União. Recuperado em http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10216.htm [ Links ]

Lima, E. A. (2004). Oficinas, laboratórios, ateliês, grupos de atividades: Dispositivos para uma clínica atravessada pela criação. In C. M. Costa & A. C. Figueiredo, Oficinas terapêuticas em saúde mental-sujeito, produção e cidadania (pp. 59-81). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Contra Capa Livraria. [ Links ]

Londero, S. (2010). Re-inventando o acolhimento em um serviço de saúde mental (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil). Recuperado em http://www.lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/18872 [ Links ]

Lussi, I. A. O., & Shiramizo, C. S. (2013). Oficina integrada de geração de trabalho e renda: Estratégia para formação de empreendimento econômico solidário. Revista de Terapia Ocupacional da Universidade de São Paulo. 24(1),28-37. doi: 10.11606/2238-6149.v24i1p28-37 [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde. (2004). Legislação em saúde mental: 1990-2004. Brasília, DF: Autor. [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. A., & M., Passos (2007). A implicação de serviços de saúde mental no processo de desinstitucionalização da loucura em Sergipe. Vivência (Natal), 1(1) 259-270. Recuperado em http://www.observasmjc.u?.br/psm/uploads/A_implica%C3%A7%C3%A3o_de_servi%C3%A7os_de_sa%C3%BAde

_mental_no_processo_de_desinstitucionaliza%C3%A7% C3%A3o_da_loucura_em_Sergipe_um_problema_cl%C3%ADnico-pol%C3%ADtico.pdf [ Links ]

Oliver, F. C., Tissi, M. C., Aoki, M., Vargem, E. de F., & Ferreira, T. G. (2002). Oficinas de trabalho: Sociabilidade ou geração de renda? Revista de Terapia Ocupacional da Universidade de São Paulo, 13(3),86-94. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2238-6149.v13i3p86-94 [ Links ]

Onocko-Campos, R. T., & Furtado, J. P. (2006). Entre a saúde coletiva e a saúde mental: Um instrumental metodológico para avaliação da rede de Centros de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPS) do Sistema Único de Saúde. Cadernos de Saúde Publica, 22(5),1053-1062. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2006000500018 [ Links ]

Pádua, F. H. P., & Salum, M. de L. (2010). Oficinas expressivas: Uma inclusão de singularidades. Psicologia USP, 21(2),457-478. doi: 10.1590/S0103-65642010000200012 [ Links ]

Pelbart, P. P. (1991). Manicômio mental: A outra face da clausura. In A. Lancetti (Ed.), Saúde e loucura: Vol. 2 (pp. 131-138). São Paulo, SP: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Pinho, L. B. D., Hernández, A. M. B., & Kantorski, L. P. (2010). Serviços substitutivos de saúde mental e inclusão no território: Contradições e potencialidades. Ciência, Cuidado e Saúde, 9(1),28-35. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v9i1.6824 [ Links ]

Portaria n. 3.088 de 23 de dezembro de 2011. (2011). Institui a Rede de Atenção Psicossocial para pessoas com sofrimento ou transtorno mental e com necessidades decorrentes do uso de crack, álcool e outras drogas, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde. Recuperado em http://www.brasilsus.com.br/legislacoes/gm/111276-3088.html [ Links ]

Rotelli, F. (2001). A instituição inventada. In M. F. S Nicácio (Ed.), Desinstitucionalização (2. ed., pp. 89-99). São Paulo, SP:Hucitec. [ Links ]

Saraceno, B. (2007). New knowledge and new hope to people with emerging mental disorders. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 1(1),3-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00001.x [ Links ]

Scheibel, A., & Hecker Ferreira, L. (2012). Acolhimento no CAPS: Reflexões acerca da assistência em saúde mental. Revista Baiana de Saúde Pública, 35(4),966. Recuperado em nseer.ibict.br/rbsp/index.php/rbsp/article/viewFile/266/pdf_79 [ Links ]

Schmidt, M. B., & Figueiredo, A. C. (2009). Acesso, acolhimento e acompanhamento: Três desafios para o cotidiano da clínica em saúde mental. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicopatologia Fundamental, 12(1),130-140. doi: 10.1590/S141547142009000100009 [ Links ]

Sistema Único de Saúde. (2010, 27 jun.-01 jul.). Intersetorial. Relatório Final da IV Conferência Nacional de Saúde Mental - Intersetorial. Brasília, DF: Conselho Nacional de Saúde. [ Links ]

Soares, A. N., & Reinaldo, A. M. S. (2010). Oficinas terapêuticas para hábitos de vida saudável: Um relato de experiência. Escola Anna Nery, 14(2),391-398. doi: 10.1590/S141481452010000200025 [ Links ]

Tavares, C. M. M., Barone, A. M., Fernandes, J. C., & Moniz, M. A. (2003). Análise de implementação de tecnologias de cuidar em saúde mental na perspectiva da atenção psicossocial. Escola Anna Nery, 7(3),342-350. Recuperado em http://eean.edu.br/detalhe_artigo.asp?id=1055 [ Links ]

Teixeira, R. R. (2001). Agenciamentos tecnosemiológicos e produção de subjetividade: contribuição para o debate sobre a transformação do sujeito na saúde. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 6(1). Recuperado em http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S141381232001000100004&lng=en&nrm=isso [ Links ]

Test, M. A., & Stein, L. I. (2000). Practical guidelines for the community treatment of markedly impaierd patients. Community Mental Health Journal, 36(1),47-60. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/cb30162e0f57b6004246 b61e5ea5ee9a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar [ Links ]

Torre, E. H. G., & Amarante, P. (2001). Protagonismo e subjetividade: A construção coletiva no campo da saúde mental. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 6(1),73-85. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232001000100006 [ Links ]

Turato, E. R. (2008). Tratado da metodologia da pesquisa clínico-qualitativa. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Vasconcellos, V. C., & Azevedo, C. S. (2010). The meanings of work and the organizational imaginary in a psychosocial care center (PCC). Interface-Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, 14(34), 563-576. Recuperado em www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/v14n34/aop1010.pdf [ Links ]

Zerbetto, S. R., Efigênio, E. B., dos Santos, N. L. N., & Martins, S. C. (2011). O trabalho em um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial: Dificuldades e facilidades da equipe de enfermagem. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem, 13(1),99-109. [ Links ]

Received: 27/11/2016 Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Teresinha Cid Constantinidis

Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia

Av. Fernando Ferrari, s/n

Vitória, ES, Brazil 29055-350

E-mail: teracidc@gmail.com

1st revision: 26/03/2017

Accepted: 31/05/2017

texto en

texto en