Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.26 no.3 Ribeirão Preto jul./set. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.3-07Pt

ARTICLE

Cross-cultural adaptation and factor structure of the brazilian version of the right-wing authoritarianism

Felipe VilanovaI; Diogo Araújo De SousaII; Silvia Helena KollerIII; AngeloBrandelli CostaIV

IOrcid.org/0000-0002-2516-9975. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

IIOrcid.org/0000-0003-4112-6649. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Universidade Tiradentes, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

IIIOrcid.org/0000-0001-9109-6674. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

IVOrcid.org/0000-0002-0742-8152. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

ABSTRACT

The most widely used scale to assess authoritarianism is the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). It assesses authoritarianism related to thoughts commonly associated to the right-wing ideology, and it is correlated to homophobia, opposition to transsexuals' civil rights, social conformity and self-categorization as a right-wing partisan. Although it has already been used in Brazilian context, there are no studies adapting it to the national context. This study sought to adapt RWA to Brazilian Portuguese and analyze its psychometric properties in the Brazilian context through exploratory factor analysis. The cross-culturally adapted version displayed a four-factor structure and good internal consistency indexes: Authoritarianism (α= 0,936), Contestation to Authority (α= 0,858), Traditionalism (α= 0,871) and Submission to Authority (α = 0,897). The instrument also displayed criterion validity between groups, as well as convergent and divergent validity. Therefore, the measure is valid and reliable for the investigation of authoritarianism in the Brazilian population.

Keywords: Authoritarianism, RWA, right-wing authoritarianism, adaptation.

After World War II, there was an interest of sociologists, philosophers, and psychologists in understanding how the rise of totalitarian regimes occurred. Various studies were made to explain how the population provided massive support to authoritarian leaders (e.g. Adorno, Frenkel-Brinswick, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950; Altemeyer, 1981; Arendt, 1975), focusing on issues such as obedience to authority (Vilanova, Beria, Costa, & Koller, 2017; Milgram, 1963). The systematic investigation on authoritarianism focusing on the individual has its origins on the studies of Adorno et al. (1950). The authors sought to evaluate which characteristics would compose the personality of someone more prone to support authoritarian regimes that they denominated as an authoritarian personality.

To quantify the tendency of submission to authoritarian leaders the "F Scale" was built (Adorno et al., 1950). In its final form, it is made of 30 items that vary from -3 (strongly disagree) to +3 (strongly agree). Although it has been the first attempt in evaluating quantitatively individual authoritarian potentials, various psychometric fragilities were pointed out, such as the presence of very vague items (e.g. "familiriaty breeds contempt", Adorno et al., 1950, p. 256) lack of reliability, presenting only affirmative phrases, which would make it prone to acquiescence bias (Duckitt, Bizumic, Krauss, & Heled, 2010; Sibley & Duckitt, 2008).

The Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer, 1981) arose as an alternative to the F scale. According to the theorical assumptions of this scale, an authoritarian personality is composed of the covariation of three personality traits: conventionalism (adherence to traditional norms and moral values), authoritarian aggression (aggressiveness directed to various people, perceived as sanctioned by authorities) and authoritarian submission (uncritical submission to established authorities). These features constitute the construct authoritarianism that stems from beliefs of the right-wing, which is evaluated in a unifactorial basis by the RWA (Altemeyer, 1981, 1996). However, the RWA (Altemeyer, 1981, 1996) also presents characteristics that compromise its psychometric properties. First, the scores on the RWA are modified significantly in social threat situations in relation to normal situations (Altemeyer, 1988; Duckitt & Fisher, 2003), which questions the validity of its conceptualization as a personality characteristic, since personality characteristics are expected to be relatively stable in different situations (Hall, Lindzey, & Campbell, 2008). Moreover, the majority of RWA's items simultaneously evaluate the traits that constitute the authoritarian personality, making it impossible to identify which part of the item was responsible for the response (Funke, 2005). For example: "Our country will be great if we honor the ways of our forefathers [conventionalism], do what the authorities tell us to do [submission], and get rid of the 'rotten apples' who are ruining everything [aggression]" (Altemeyer, 1996, p. 13). Lastly, the conceptualization of authoritarianism as a unifactorial construct can generate impasses about the identification of individuals that tend to be submissive to authority but not aggressive and vice-versa (Passini, 2015).

Facing the fragilities of RWA (Altemeyer, 1981) Duckitt and collaborators (2010) proposed modifications to the instrument. Initially proposing a change in the definition of the RWA's components. They were no longer defined as personality traits but rather defined as independent social attitudes for two reasons: (1) the items that constitute the RWA consist of propositions about social themes; (2) social attitudes are more variable than personality traits, thus being more in agreement with studies that demonstrate significant variation in the RWA's scores (e.g. Duckitt & Fisher, 2003). Each of the RWA's components would thus cover different attitudinal expressions that would favor or oppose the subordination of individual liberty to the collective and social authorities (Duckitt et al., 2010).

Duckitt and collaborators (2010) then composed a questionnaire with items from the classic versions of the RWA (Altemeyer, 1981, 1988, 1996, 1998), items from the F scale (Adorno et al., 1950) and other authoritarianism scales (Cherry & Byrne, 1977; Kohn, 1974; Lee & Warr, 1969). However, the items from RWA which evaluate simultaneously more than one cluster of social attitudes (previously defined as personality traits) were dismembered, in such way that each item would evaluate only one set. Items that expressed homophobic attitudes were also excluded because of the possibility of artificially increasing correlation with measures of prejudice. The survey contained 117 items that were submitted to the judgment of experts and successive international studies to refine the instrument.

A new version of the RWA was then proposed (Duckitt et al., 2010). It is composed of 36 items divided equally between three independent factors: Conservatism (tendency to favour institutional or group authorities in an uncritical and submissive way), Authoritarianism (tendency to support the use of coercive methods of social control, such as death penalty) and Traditionalism (adhesion and support of traditional moral values; Duckitt et al., 2010). The factorial structure of the proposed version is in consonance with studies that demonstrate the better adequacy of the empirical data obtained with the RWA to a trifactorial model instead of a unifactorial one (Funke, 2005; Mavor, Louis, & Sibley, 2010).

Since its development, the RWA has already been used in several studies. It is directly associated with homophobia (Adams, Nagoshi, Filip-Crawford, Terrell, & Nagoshi, 2016; Crawford, Brandt, Inbar, & Mallinas, 2016; Goodnight, Cook, Parrott, & Peterson, 2014; Sousa, 2016; Stones, 2006) social conformity (Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis, & Birum, 2002) attitudes favourable to torture (Benjamir, 2016), self-declaration as a right-wing partisan (Passini, 2015), low levels of schooling (Carvacho et al., 2013) and opposition to transsexual civil rights (Tee & Hegarty, 2006). The relevance of the themes to which RWA can be related is clear, specially considering the current political moment in Brazil which can be better understood through authoritarianism studies. However, the RWA tends to show different patterns of correlations between cultures (Duckitt et al., 2010), making the analysis of its psychometric properties in diferent contexts fundamental to obtain accurate results.

The present study is the first one which seeks to adapt and validate the RWA version proposed by Duckitt et al. (2010) in a context different than the ones observed for the creation of the instrument. Other RWA versions have already been adapted to different contexts such as for Argentine (Etchezahar, 2012), South Africa (Duckitt, 1993) and Turkey (Güldü, 2011). Whereas the adapted versions in Argentine (Etchezahar, 2012) and Turkey (Güldü, 2011) displayed a two-factor structure the southafrican version (Duckitt, 1993) displayed a one-factor structure. In a recent study the adapted RWA version for South Africa (Duckitt, 1993) had its psychometric properties reanalyzed and it was verified that it presented a three-factor structure with inadequate internal consistency indexes (Gray & Durrheim, 2006). Therefore there is a cross-cultural and temporal variation in the factor structure of the different instruments that evaluate authoritarianism that highlights the influence of the culture on authoritarianism and reinforces the need of reevaluation of its psychometric properties in different contexts.

Although an adaptation study of RWA for Brazil has not yet been done, it was already used in the national context in an unsystematic manner (e.g. Barros, Torres, & Pereira, 2009; Cantal, Milfont, Wilson, & Gouveia, 2015; Guimarães, Torres, & de Faria, 2005; Santos, 2015; Torres, de Faria, Guimarães, & Martignoni, 2007; Vilela, 2012) both in its classical form (Altemeyer, 1988) and in its alternative form (Duckitt et al., 2010). Therefore, in order to improve the accuracy of nationally obtained results, the objective of the present study is to adapt the RWA proposed by Duckitt and collaborators (2010) to the Portuguese language and analyze their psychometric properties in the Brazilian context. The evaluated psychometric properties were: factor structure, internal consistency, criterion validity between different political groups and prejudice against sexual and gender diversity scores.

Method

Participants

Participated in this study 518 individuals aged between 18 and 79 years (M = 39.31; SD = 17.93). Of these, 307 (59.4%) live in the South Region, 184 (35.6%) live in the Southeast Region, 18 (3.5%) live in the Northeast Region and 8 (1.5%) live in the Central-West region. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characterization of the sample in terms of ethnicity, schooling, socioeconomic class, and religion.

Procedures

After the authorization granted by the author of the original scale, the process of transcultural adaptation of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA; Duckitt et al., 2010) began. The English-Portuguese translation was conducted independently by two expert researchers in social psychology, native Brazilians and fluent in English. Then, two experts in psychological assessment evaluated the translated items and suggested changes. Subsequently, three volunteers that denominated themselves as right-wing militants were asked to choose the best proposal of adaptation for such instruments, having the possibility to suggest an alternative to the proposals. The resulting items were then back-translated by one of the researchers who carried out the first stage of translation and then sent it to the author of the original scale. In all stages, the relevant aspects of the validation of psychological instruments between cultures (Borsa, Damásio, & Bandeira, 2012) were taken into account, such as conceptual and idiomatic equivalence. The content validty analysis method used in all steps was the consent between experts or peers.

The collection of data with the Brazilian version of the scale was done through an online form. Participants were invited to participate through a disclosed link posted on a social network between October and November 2016. An advertisement promoting the survey was generated via a social network for greater reach. Before answering the questions from the survey, the subjects expressed their agreement with the Informed Consent Form. Their anonymity was guaranteed and only the researchers had access to their data, according to ethical considerations from the National Health Council Resolution n. 510/2016 on research with human beings. The sample was recruited through convenience. The Research Ethics Committee of the university to which it is attached approved the project of the present study.

Instruments

The complete instrument was composed of a sociodemographic questionnaire investigating the following variables: State and city of residence, gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, socioeconomic class, level of schooling, in which type of school (public or private) they studied for most of their lives, if they have attended college (if yes, whether it was public or private), if they have religious or spiritual belief and which, and what is the degree of religious participation. It was later asked whether the individual is affiliated with any political party (and which) and in which part of the political spectrum (center-left, left, center, center-right, right or none) they would stand. Afterward, participants responded to the Brazilian version of RWA (Duckitt et al., 2010) and, finally, the Revised Scale of Prejudice Against Sexual and Gender Diversity (Costa, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2015; Costa, Machado, Bandeira, & Nardi, 2016).

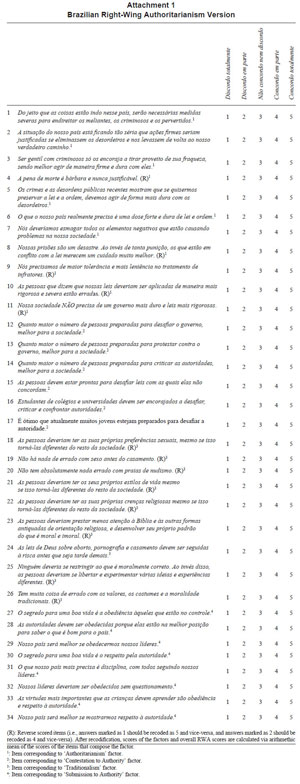

Right-Wing Authoritarianism. The Right-Wing Authoritarianism (Duckitt et al., 2010) is a self-report measure composed of three factors with 12 items each: (1) authoritarianism; (2) conservatism; (3) traditionalism. In its development study, it displayed good psychometric properties (RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.065, GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.95, Duckitt et al., 2010). The portuguese version, which is described in the results section, was composed of items that ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Revised Scale of Prejudice Against Sexual and Gender Diversity. The Revised Scale of Prejudice against Sexual and Gender Diversity (Costa et al., 2016) is a one-dimensional self-report measure composed of 18 items. Its psy

chometric properties were evaluated through IRT (Rasch family model), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and criterion validity. The principal contrasts analysis displayed the presence of an eigenvalue component = 22.4, explaining 55.5% of the variance of the items. Furthermore, the unifactorial model displayed good fits in the CFA (X2/df= 43,02, p < .001, CFI = 0,96, TLI = 0,96, RMSEA 0,07) and the scale satisfactorily differentiated groups that historically have been differentiated through prejudice measures' scores. In the presente sample the instrument displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.94) and the items ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Data Analysis

The Brazilian version of the RWA was subjected to an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to investigate its factorial structure in the new context (Damásio, 2012) and a parallel analysis in order to obtain eigenvalues through random permutation of observed data. First, two methods of evaluation were used to observe the fit of the data matrix to factorization: The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criterion and the Bartlett sphericity test. After, a principal axis factoring EFA, with oblique oblimin rotation. The number of retained factors was delimited from the Kaiser-Guttman criterion (i.e., eigenvalue > 1) and displaying higher eigenvalues in the EFA than in the parallel analysis (O'Connor, 2000). Factor loadings above 0.40 were considered adequate for retention of items in the factors.

To investigate its reliability by internal consistency, Cronbach's alphas were calculated from the total RWA score and its subscales. To investigate evidence of RWA criterion validity between groups, analyses of variance (ANO-VAs) were performed among participants who identified themselves at different points in a political spectrum (left; center-left; center; right-center; right; none of the above). Finally, Pearson correlations were made between the RWA scores and the Revised Scale of Prejudice against Sexual and Gender Diversity (Costa et al., 2016).

Results

Cross-Cultural Adaptation

Based on suggestions from the experts on psychological evaluation, some of the RWA items with more than one syntactic object or subject were dismembered so that there was only one of these per item. The item "our country will be better if we show respect for authority and obey our leaders" became "nosso país será melhor se mostrarmos respeito à autoridade" and "nosso país será melhor se obedecermos nossos líderes". The original item "people should be ready to protest against and challenge laws they do not agree with" was dismembered in "as pessoas devem estar prontas para protestar contra leis com as quais elas não concordam" and "as pessoas devem estar prontas para desafiar leis com as quais elas não concordam". The item "the more people there are that are prepared to criticize the authorities, challenge and protest against the government, the better it is for society" was dismembered in "quanto maior o número de pessoas preparadas para criticar as autoridades, melhor para a sociedade", "quanto maior o número de pessoas preparadas para desafiar o governo, melhor para a sociedade" and "quanto maior o número de pessoas preparadas para protestar contra o governo, melhor para a sociedade". The item "the real keys to the 'good life' are respect for authority and obedience to those who are in charge" was dismembered in "o segredo para uma boa vida é o respeito pela autoridade" and "o segredo para uma boa vida é a obediência àqueles que estão no controle". The item originally "everyone should have their own lifestyle, religious beliefs, and sexual preferences, even if it makes them different from everyone else" was dismembered in "as pessoas deveriam ter os seus próprios estilos de vida mesmo se isso torná-las diferentes do resto da sociedade", "as pessoas deveriam ter as suas próprias preferências sexuais mesmo se isso torná-las diferentes do resto da sociedade" and "as pessoas deveriam ter as suas próprias crenças religiosas mesmo se isso torná-las diferentes do resto da sociedade". Lastly, the item "people who say our laws should be enforced more strictly and harshly are wrong. We need greater tolerance and more lenient treatment for lawbreakers" was divided into "as pessoas que dizem que nossas leis deveriam ser aplicadas de maneira mais rigorosa estão erradas" and "nós precisamos de maior tolerância e mais leniência no tratamento de infratores".

The cross-culturally adapted version of the scale used in the data collection for investigation of its psychometric properties was composed of 44 items, eight more than the original scale due to the described dismemberments. This version was submitted to the right-wing militants' evaluation for pre-test, which didn't suggest any modifications. The back-translated version of this version was then sent to the original author of the scale, who approved and didn't make any modifications to it.

Factor Structure

In the preliminary evaluation of the adequacy of the data matrix, the KMO index was 0.964, considered great. Bartlett's sphericity test results also indicated suitability for factorization (p < .001). The EFA indicated a five-factor solution. The eigenvalues obtained through the EFA were respectively 17.51; 2.40; 1.73; 1.50 and 0.911. The fifth factor violated the Kaiser-Guttman criterion and was the only one that displayed lower eigenvalue in the EFA than in the parallel analysis (eigenvalue displayed in parallel analysis for factor 1 = 1.605; for factor 2 = 1.539; for factor 3 = 1.492; for factor 4 = 1.450; for factor 5 = 1.413). Hence the final factor solution was a four-factor one, namely Authoritarianism (AT), Contestation to Authority (CA), Traditionalism (TR) and Submission to Authority (SA). The four factors accounted cumulatively for 52.69% of the variance of the scale (Table 2).

Ten items had factor loadings below 0.40 in all factors: "As pessoas deveriam parar de ensinar crianças a obedecer à autoridade"; "O país irá prosperar se os jovens pararem de experimentar drogas, álcool e sexo, e prestarem mais atenção aos valores de família"; "Um governo forte e rígido vai prejudicar nosso país e não o ajudar"; "Os tribunais estão certos em serem mais brandos com traficantes de drogas. Punição não adiantaria de nada em casos como esses"; "As pessoas devem ser permitidas a fazer discursos e escrever livros incitando a derrubada do governo"; "As pessoas devem estar prontas para protestar contra leis com as quais elas não concordam"; "A mídia radical está envenenando as mentes dos nossos jovens"; "É importante que preservemos nossos valores tradicionais e padrões morais"; "Os novos estilos de vida e comportamentos radicais e pecaminosos de muitos jovens poderá destruir nossa sociedade"; and "Os modos e valores tradicionais ainda mostram a melhor forma de se viver" (Table 2).

Through content analysis of the items which compose the four factors it is possible to note that the first factor grouped items related to the tendency to withdraw civil liberties and support severe punitive measures, being denominated 'Authoritarianism'. The second factor brought together items associated with the tendency to criticize, challenge, and protest against authority, being called 'Contestation to Authority'. The third factor congregated items associated with traditional values and moral standards, being called 'Traditionalism'. The fourth factor, however, brought together items related to the propensity to obey and respect authorities, being called 'Submission to Authority'.

All the factor scores were calculated through arithmetic mean of the items which compose each factor. The responses to the items which displayed negative factor loadings in the factors 'Authoritarianism', 'Contestation to Authority' and 'Submission to Authority' were recoded in order to reverse its values for the calculation of the scores of these factors (i.e. answers marked as 1 were recoded as 5 and vice-versa, and answers marked as 2 were recoded as 4 and vice-versa). For the 'Traditionalism' factor, the answers to all items were recoded in order to invert its values so that the higher the score, the higher the traditionalism level of the reporter.

In order to calculate the overall RWA score, the answers to all items that compose the 'Contestation to Authority' factor were recoded to invert its values before computing the score of this factor. Then the overall score was calculated through arithmetic mean of the four factors' scores. Hence, the higher the overall RWA score, the higher the levels of authoritarian and traditionalist attitudes and the tendency to submit to authority.

Cronbach's alpha of the RWA total score (all items together, with those with negative factorial load inversely encoded) reflects high internal consistency (α = 0.957; CI 95% [0.952; 0.962]). Similarly, the coefficients of the subscale scores were also high: Authoritarianism (α = 0.936; CI 95% [0.928; 0.944]); Contestation to authority (α = 0.858; CI 95% [0.840; 0.875]); Traditionalism (α = 0.871; CI 95% [0.855; 0.866]); And Submission to Authority (α = 0.897; CI 95% [0.884; 0.909]).

Evidence of Criterion Validity among Groups

Figure 1 present the results for the RWA scores among the groups of people who identified themselves at different points in a political spectrum composed of left, center-left, center, right-center, right and "unidentified".

It can be seen that in 'Authoritarianism' the scores were progressively higher on the left-right spectrum, and the more to the right, the higher the score in this factor [F (5, 512) = 155.45, p < .001, η2 = 0.60]. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted to assess which groups differed significantly. There were significant differences among all groups (p <.05) except those who declared themselves at the center of the political spectrum and those who declared they were not in any part of the spectrum. In the 'Contestation to Authority' scores were progressively smaller in the left-right spectrum [F(5, 512) = 63.65, p < .001, η2 = 0.38], and according to Bonferroni post-hoc tests, there wasn't significant difference only between right and center-right. In 'Traditionalism' factor, scores were progressively higher left-right spectrum [F(5, 512) = 75.76, p < .001, η2 = 0.42], and post-hoc Bonferroni tests revealed that there was no significant difference only between left and center-left, between the center and those who declared they did not fit into any part of the political spectrum, as well as between the center-right and those who did not fit the political spectrum. Finally for the factor 'Submission to Authority' scores were also progressively higher in the left-right spectrum [F (5, 512) = 53.20, p < .001, η2 = 0.34], and there were no significant differences according to post-hoc Bonferroni tests only between the left and center-left, between the center and center-right and between the center and those who did not fit the political spectrum.

The overall RWA score was also progressively higher on the left-right spectrum [F(5, 512) = 167.841, p < .001, η2 = 0.62], not having according to post-hoc Bonferroni tests significant differences between left and center-left, between center and those who did not fit the political spectrum, as well as between center-right and those who did not fit the political spectrum.

As an evidence of convergent criterion validity, significant positive correlations were found between scores of the Revised Scale of Prejudice against Sexual and Gender Diversity and the overall RWA score (r = 0.746; p < .001), the sub scores of 'Authoritarianism' (r = 0.633; p < .001); 'Traditionalism' (r = 0.784; p < .001) and 'Submission to Authority' (r = 0.639; p < .001). In contrast, a significant negative correlation was found between the scores of the Revised Scale of Prejudice against Sexual and Gender Diversity and the sub scores of 'Contestation to Authority' (r = -0.441; p < .001).

Discussion

The present study translated and adapted to Brazilian Portuguese the Right-wing Authoritarianism (RWA; Duckitt et al., 2010). The internal consistency indexes (Cronbach's alphas) presented were superior to those of previous studies that used different versions of the RWA in Brazil (Barros et al., 2009; Guimarães et al., 2005; Torres et al., 2007; Vilela, 2012). Furthermore the proposed factor solution explained a larger part of the variance of the scale scores than previous studies (Barros et al., 2009; Guimarães et al., 2005; Torres et al., 2007).

Some items proposed in this cross-cultural adaptation did not display adequate factor loadings on any of the factors. One of them was an item dismembered because it originally presented more than one subject or object: "As pessoas devem estar prontas para protestar contra leis com as quais elas não concordam". In counterpart, other analog dismembered item was retained: "As pessoas devem estar prontas para desafiar leis com as quais elas não concordam". In this case, it is noticed that the idea of 'desafio', of the retained item, was stronger than 'protesto' of the eliminated item. The item "Os tribunais estão certos em serem mais brandos com traficantes de drogas. Punição não adiantaria de nada em casos como esses" also did not display adequate factor loadings on any factor. The duplicity of information may have impaired comprehension. The experts did not suggest division, in the understanding that it would be the same information in the two sentences; however, comprehension may have been impaired, as in a case where the subject agrees with milder sentences but disagrees with the effectiveness of punishment.

A set of items related to the idea of values was also not retained in any factor: "Os modos e valores tradicionais ainda mostram a melhor forma de se viver"; and "É importante que preservemos nossos valores tradicionais e padrões morais". The idea of traditional values may not be completely comprehended in the Brazilian context. A single item that mentioned values remained in the adaptation: "Tem muita coisa de errado com os valores, os costumes e a moralidade tradicionais". The item contextualizes what it would be such values mentioning customs and traditional morals. Future generations of the RWA can modify the wording of the original items related to values using the idea of traditional customs and morality. Future RWA versions can test modifications in the writing form of the items related to values using the idea of traditional morality.

Two other items that did not reach the 0.40 cut-off score regarded youth, sexual and substance use: "O país irá prosperar se os jovens pararem de experimentar drogas, álcool e sexo, e prestarem mais atenção aos valores de família"; and "Os novos estilos de vida e comportamentos radicais e pecaminosos de muitos jovens poderá destruir nossa sociedade". The items mention sexuality and alcohol consumption, which present distinct characteristics in Brazil when compared to the Anglo-Saxon context. For example, in the Brazilian context, sexual abstinence policies for the control of sexually transmitted infections have never been proposed, as has happened in other countries (Santelli et al., 2006). Although sectors of the national congress have discussed similar proposals recently (Carrara, 2012), it is possible that the social representation of an authoritarian attitude related to sexual morality is inert from the population's point of view. The same in relation to alcohol consumption, which among young people reaches 81.7% (Cerutti, Ramos, & Argimon, 2015).

The item "As pessoas devem ser permitidas a fazer discursos e escrever livros incitando a derrubada do governo"; and the item "A mídia radical está envenenando as mentes dos nossos jovens" were also excluded of the final Brazilian version. In relation to the first one, it is hypothesized that the low level of reading in Brazil distances the direct comprehension in writing of books with the authoritarian politics [44% of the Brazilian population does not read and 30% never bought a book (Failla, 2016)]. In relation to the second item, the original version mentioned the idea of "trashy magazines and radical literature" and the attempt of adaptation tried to approach the Brazilian context to the original meaning of the item, probably without success. Militants have suggested the permanence of the item perhaps because they are immersed in a context where the political jargon using this expression (radical media) is more prevalent. However, our research shows that the general population may not understand this type of vocabulary. Perhaps the idea of radical media connected to an authoritarian political vision does not exist in Brazil.

Finally, the item "Um governo forte e rígido vai prejudicar nosso país e não o ajudar"; and the item "As pessoas deveriam parar de ensinar crianças a obedecer à autoridade" were not retained. In Brazil, we have the prevalence of two visions that contrast with the view of the global north from where these scales come from. The first of these is the conservative liberal view that congregates people who advocate minimum state from the standpoint of economic and social regulation while advocating a conservative position on behavior regulation (Datafolha, 2014). The second view may concern the authoritarian left, that is, leftist positions that advocate not only state regulation but also submission to authoritarian leaders (de Regt, Mortelmans, & Smits, 2011). Probably, this type of distribution made that these items were not in harmony with the rest of the scale.

It is noticed that the factor originally denominated 'Conservatism' was subdivided in the Brazilian AFE. The items that originally presented negative load in this factor were agglutinated in a new factor in the present study. Because it was related to ideas of criticizing, challenging, and protesting against authority, it was called Contestation to Authority. The literature has described a similar situation (Mavor et al., 2010), however, other authors preferred to maintain the trifactorial structure via confirmatory factor analyses, since it also had good fit indices. In the current study, it was decided to maintain the resulting structure from the EFA due to the sample size limitation to test the two concurrent models via CFA (i.e., the original trifactorial strucutre and the empirical model proposed via EFA in this study). In addition, the term 'Conservatism' was modified to 'Submission to Authority'. This is because although respect and obedience to authority are part of the conservative doctrine (Coutinho, 2014; Scruton, 2015), this doctrine comprehends much more than only this. Thus, to use the term 'Conservatism' is less conceptually accurate than the term 'Submission to Authority'.

The factor structure obtained is also different than the ones obtained in previous studies with different RWA versions (e.g. Etchezahar, 2012). As authoritarianism is conceptualized as a social attitude (Duckitt et al., 2010) it is plausible that the instruments which measure it vary as the society changes as it has already been pointed out (Gray & Durrheim, 2006). Therefore the periodic reevaluation of RWA psychometric properties is essential not only periodically but also when applying it to samples that have sociodemographic characteristics other than the ones present in the sample used in this study which consequently may express authoritarianism in different ways.

The overall RWA score, as well as the sub-factors means 'Authoritarianism', 'Traditionalism', and 'Submission to Authority', were sequentially higher in participants who self-declared in the left-right spectrum, demonstrating good criterion validity, since it evaluates social attitudes stemming from beliefs related to the political right wing (Passini, 2015). In the factor 'Contestation to Authority', the mean in the left-right spectrum was sequentially lower, and this reinforces the validity of the scale.

Finally, the average of scores from the Scale of Prejudice against Sexual and Gender Diversity correlated positively with the mean scores on the factors 'Traditionalism', 'Authoritarianism', and 'Submission to Authority', correlating negatively with the mean scores on the factor 'Contestation to Authority'. This result was expected since the literature demonstrates a robust direct relationship between authoritarianism and homophobia (Adams et al., 2016; Goodnight et al., 2014; Sousa, 2016; Stones, 2006) and between opposition to civil rights of transsexuals as well (Tee & Hegarty, 2006).

The present study has some limitations that must be taken into account. First, the political spectrum assessed is very broad and does not specify subdivisions of political positions, such as liberals, conservatives, anarchists and others. To investigate better the phenomenon of authoritarianism in the Brazilian context, future studies may use other forms of political categorization. Second, a considerable portion of the sample declared themselves of the white ethnicity, not corresponding to the ethnic diversity of Brazilian society. Third, there were few participants from the Northeast, Center-West and none from the North region, which also does not correspond to the Brazilian population distribution. Future studies should investigate variations of the scores with samples that are more representative of the national profile so that a more accurate intercultural comparison is possible.

Despite the limitations, the results of the present study indicate that the RWA is valid and reliable for application in the Brazilian context. The four-factor structure of the Brazilian version of the scale (Attachment 1) displayed good indices of internal consistency both overall and in its factors. The RWA is an adequate instrument to investigate Authoritarianism in the Brazilian population. Future studies can propose a shorter version of RWA since the literature proposes that Cronbach's alpha higher than .90 may indicate the existence of redundant items (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Future studies can also use confirmatory factor analyses, predictive validity tests and explicative models using RWA.

References

Adams, K. A., Nagoshi, C. T., Filip-Crawford, G., Terrell, H. K., & Nagoshi, J. L. (2016). Components of gender-nonconformity Prejudice. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3-4),185-198. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1200509 [ Links ]

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brunswick, E., Levinson, D., & Sanford, N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba Press. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The Authoritarian Specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other "authoritarian personality." In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 47-92). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. (1975). Elemente und Ursprünge totaler Herrschaft [As origens do totalitarismo]. New York: Harcourt. [ Links ]

Barros, T. S., Torres, A. R. S., & Pereira, C. (2009). Autoritarismo e adesão a sistemas de valores psicossociais. Psico-USF, 14(1),47-57. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712009000100006 [ Links ]

Benjamin, A. J., Jr. (2016). Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Attitudes toward Torture. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(6),881-888. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2016.44.6.881 [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: algumas considerações. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 22(53),423-432. doi: 10.1590/S0103-863X2012000300014 [ Links ]

Cantal, C., Milfont, T. L., Wilson, M. S., & Gouveia, V. V. (2015). Differential effects of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on dimensions of generalized prejudice in Brazil. European Journal of Personality, 29,17-27. doi: 10.1002/per.1978 [ Links ]

Carrara, S. (2012). Políticas e Direitos Sexuais no Brasil Contemporâneo. Bagoas-Estudos Gays: Gêneros e Sexualidades, 4(5),132-148. [ Links ]

Carvacho, H., Zick, A., Haye, A., González, R., Manzi, J., Kocik, C., & Bertl, M. (2013). On the relation between social class and prejudice: The roles of education, income, and ideological attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43,272-285. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1961 [ Links ]

Cerutti, F., Ramos, S. P., & Argimon, I. I. L. (2015). A implicação das atitudes parentais no uso de drogas na adolescência. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 18(2),173-181. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2015.18.2.15 [ Links ]

Cherry, F., & Byrne, D. (1977). Authoritarianism. In T. Blass (Ed.), Personality variables in social behavior (pp. 109-133). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2015). Avaliação do preconceito contra diversidade sexual e de gênero: Construção de um instrumento. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 32(2),163-172. doi: 10.1590/0103-166X2015000200002 [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Machado, W. L., Bandeira, D. R., & Nardi, H. C. (2016). Validation Study of the Revised Version of the Scale of Prejudice Against Sexual and Gender Diversity in Brazil. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(11),1446-1463. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1222829 [ Links ]

Coutinho, J. P. (2014). As ideias conservadoras. São Paulo, SP: Três Estrelas. [ Links ]

Crawford, J. T., Brandt, M. J., Inbar, Y., & Mallinas, S. R. (2016). Right-Wing Authoritarianism predicts Prejudice Equally Toward "Gay Men and Lesbians" and "Homosexuals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(2),e31-e45. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000070 [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2012). Uso da Análise Fatorial Exploratória em Psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica, 11(2),213-228. [ Links ]

Datafolha. (2014). Intenção de voto para presidente da república. Recuperado em http://media.folha.uol.com.br/datafolha/2014/09/08/matriz-direita-x-esquerda.pdf [ Links ]

De Regt, S., Mortelmans, S., & Smits, T. (2011). Left-wing authoritarianism is not a myth, but a worrisome reality. Evidence from 13 Eastern European countries. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 44,299-308. doi: 10.1016/j.postcomstud.2011.10.006 [ Links ]

Duckitt, J. (1993). Right-Wing Authoritarianism among White South African Students: Its measurement and correlates. The Journal of Social Psychology, 133(4),553-563. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1993.9712181 [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., Bizumic, B., Krauss, S. W., & Heled, E. (2010). A Tripartite Approach to Right-Wing Authoritarianism: The Authoritarianism-Conservatism-Traditionalism Model. Political Psychology, 31(5),685-715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology, 24,199-222. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00322 [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The Psychological Bases of Ideology and Prejudice: Testing a Dual Process Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1),75-93. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.1.75 [ Links ]

Etchezahar, E. (2012). Las Dimensiones del Autoritarismo: análisis de la Escala de Autoritarismo del Ala de Derechas (RWA) en una Muestra de Estudiantes Universitarios de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Psicologia Política, 12(25),591-603. [ Links ]

Failla, Z. (2016). Retratos da leitura no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Sextante. [ Links ]

Funke, F. (2005). The Dimensionality of Right-Wing Authoritarianism: Lessons from the Dilemma between Theory and Measurement. Political Psychology, 26,195-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00415.x [ Links ]

Goodnight, B. L., Cook, S. L., Parrott, D. J., & Peterson, J. L. (2014). Effects of Masculinity, Authoritarianism, and Prejudice on Antigay Aggression: A Path Analysis of Gender-Role Enforcement. Psychology of Men, & Masculinity, 15(4),437-444. doi: 10.1037/a0034565 [ Links ]

Gray, D., & Durrheim, K. (2006). The Validity and Reliability of Right-Wing Authoritarianism in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 36(3),500-520. doi: 10.1177/008124630603600305 [ Links ]

Guimarães, J. G., Torres, A. R. R., & de Faria, M. R. G. V. (2005). Democracia e violência policial: O caso da Polícia Militar. Psicologia em Estudo, 10(2),263-271. doi: 10.1590/S141373722005000200013 [ Links ]

Güldü, Ö. (2011). SAĞ KANAT YETKECİLİĞİ ÖLÇEĞİ: UYARLAMA ÇALIŞMASI. Ankyra: Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 2(2),27-51. doi: 10.1501/sbeder_0000000033 [ Links ]

Hall, C. S., Lindzey, G., & Campbell, J. B. (2008). Teorias da Personalidade (5. ed.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Kohn, P. (1974). The Authoritarianism-rebellion Scale: A balanced F scale with left-wing reversals. Sociometry, 35,176-189. doi: 10.2307/2786557 [ Links ]

Lee, R., & Warr, P. (1969). The Development and Standardization of a balanced F Scale. Journal of General Psychology, 81,109-129. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1969.9710776 [ Links ]

Mavor, K. I., Louis, W. R., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). A bias-corrected Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Right-Wing Authoritarianism: Support for a three-factor Structure. Personality and Individual Differences, 48,28-33. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.08.006 [ Links ]

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of Obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67,371-378. doi: 10.1037/h0040525 [ Links ]

O'Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS Programs for determining the Number of Components using Parallel Analysis and Velicer's MAP Test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 32(3),396-402. doi: 10.3758/BF03200807 [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2015). Different Ways of being Authoritarian: The distinct Effects of Authoritarian Dimensions on Values and Prejudice. Political Psychology, 38(1),73-86. doi: 10.1111/pops.12309 [ Links ]

Santelli, J., Ott, M. A., Lyon, M., Rogers, J., Summers, D., & Schleifer, R. (2006). Abstinence and abstinence-only education: A review of US policies and programs. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(1),72-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.006 [ Links ]

Santos, L. C. O. (2015). Aspectos religiosos, educacionais e valorativos da intenção de voto (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil). [ Links ]

Scruton, R. (2015). O que é Conservadorismo. São Paulo, SP: É Realizações. [ Links ]

Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(3),248-279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226 [ Links ]

Sousa, C. P. G. (2016). A influência do autoritarismo e do locus de controlo nas atitudes homofóbicas (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidade e Tecnologias, Lisboa, Portugal). [ Links ]

Stones, C. R. (2006). Antigay Prejudice among Heterosexual Males: Right-Wing Authoritarianism as a stronger predictor than Social-Dominance Orientation and Heterosexual Identity. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(9),1137-1150. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2006.34.9.1137 [ Links ]

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making Sense of Cronbach's Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2,53-55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [ Links ]

Tee, N., & Hegarty, P. (2006). Predicting Opposition to the Civil Rights of Trans Persons in the United Kingdom. Journal of Community, & Applied Social Psychology, 16,70-80. doi: 10.1002/casp.851 [ Links ]

Torres, A. R. R., de Faria, M. R. G. V., Guimarães, J. G., & Martignoni, T. V. L. (2007). Análise Psicossocial do Posicionamento de Adolescentes com relação à Violência Policial. Psicologia em Estudo, 12(2),229-238. doi: 10.1590/S141373722007000200003 [ Links ]

Vilanova, F., Beria, F.M., Costa, A.B., & Koller, S.H. (2017). Deindividuation: From Le Bon to the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects. Cogent Psychology, 4:1308104. DOI: 10.1080/23311908.2017.1308104 [ Links ]

Vilela, M. O. (2012). A Personalidade Autoritária do Chão de Fábrica à Gerência: Um estudo aplicando a Escala RWA adaptada da Escala "F" de Adorno (Dissertação de mestrado, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil). [ Links ]

Received: 16/05/2017  Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Felipe Vilanova

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2600, sala 104

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil 90.035-003

Fone: (51) 3308-5150

E-mail: felipevilanova2@gmail.com

1st revision:20/05/2017

2nd revision: 13/08/2017

Accepted: 16/08/2017

texto en

texto en