Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.27 no.2 Ribeirão Preto abr./jun. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2019.2-03

ARTICLE

Assessment of an academic skills development program for youths in juvenile correctional facilities

Avaliação de um programa de desenvolvimento de habilidades acadêmicas em adolescentes no regime de internação em unidade de socioeducação

Evaluación de un programa de desarrollo de habilidades académicas para adolescentes internados en unidad de socio educación

Vanessa Harmuch Perez ErlichI; Murilo Ricardo ZibettiII; Paula Inez Cunha GomideIII

IOrcid.org/0000-0003-0573-1649. Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil

IIOrcid.org/0000-0002-8934-5640. Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil

IIIOrcid.org/0000-0003-3361-8993. Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brasil

ABSTRACT

School deficit is considered a risk factor for the development of antisocial behavior. This study assessed the efficacy of individual program on academic skills for adolescents admitted to juvenile detention. The sample consisted of 18 adolescents, nine who received the intervention (experimental group) and nine in the control group. The schooling activities were developed in a range of 12 to 18 weeks with two to four hours per week and efficacy was measured by School Performance Test (SPT) that evaluates writing, reading and arithmetics. The results of the comparison between pretest and post-test showed a statistically significant increase in the experimental group's math skills (Z = -2.673, p = .008) and overall score (Z = -2.549, p = .012). Calculated via the STP the average educational lag at the time of the pretest was 8.3 years for the experimental group and 8.9 years for the control group. Subsequent to the intervention, the average lag dropped to 7.3 years for the experimental group and remained to 8.6 years for the control group. This intervention proved to be a promising technique to reduce academic deficits in adolescents from juvenile detention.

Keywords: Juvenile offenders, intervention, academic skills, learning support.

RESUMO

O déficit escolar é considerado um fator de risco para o desenvolvimento do comportamento antissocial. Esse estudo avaliou a eficácia de um programa para o desenvolvimento de habilidades acadêmicas para adolescentes em conflito com a lei. A amostra foi composta por 18 adolescentes, nove receberam a intervenção (grupo experimental) e nove participaram do grupo controle. As atividades de estimulação foram desenvolvidas entre duas e quatro horas semanais em um período entre 12 e 18 semanas. A eficácia do programa foi medida pelo Teste de Desenvolvimento Escolar (TDE) que avalia habilidades de escrita, leitura e aritmética. Os resultados da comparação entre pré teste e pós teste demonstraram que o grupo experimental teve melhoras significativas nas habilidades aritméticas (Z = -2,673, p = 0,008) e no escore total (Z = -2,549, p = 0,012). Medida pelo TDE a média de atraso escolar no pré teste foi de 8,3 anos no grupo experimental e de 8,9 anos no grupo controle. Após a intervenção a média caiu para 7,3 anos no grupo experimental e se manteve em 8,6 anos no grupo controle. Essa intervenção demonstrou ser uma técnica promissora para reduzir déficits escolares em adolescentes em conflito com a lei.

Palavras-chave: Adolescente em conflito com a lei, intervenção, habilidades acadêmicas, reforço escolar.

RESUMEN

El déficit escolar se considera un factor de riesgo para el desarrollo del comportamiento antisocial. Esta investigación evaluó un programa de escolarización individual, en la modalidad refuerzo escolar, con adolescentes internados en unidad de socio educación. La muestra se constituyó de 18 adolescentes, nueve que recibieron la intervención y nueve en grupo control. Las actividades de escolarización se desarrollaron en un intervalo de 12 a 18 semanas, con duración de dos a cuatro horas por semana. Sus efectos fueron medidos por el Teste de Desarrollo Escolar (STP) que evaluó lectura, escritura y aritmética. Los resultados de la comparación del pre con el pos test demostraron que hubo aumento significativo de aprendizaje en aritmética (Z = -2.673, p <0,008) y en la puntuación total (Z = -2,549, p <0,012) en el grupo objetivo. El promedio del desfase escolar en pre-test, calculado por el STP, fue de 8,3 años para el grupo objetivo y 8,9 años para el control; después de la intervención promedio el desfasaje escolar cayó a 7,3 años para el grupo objetivo y se mantuvo en 8,6 para el control. La intervención en la escolarización se mostró prometedora para reducir el déficit escolar de adolescentes en régimen de internación.

Palabras clave: Adolescentes em conflito com la ley, infratores, intervencione, habilidades académicas.

Antisocial behavior involves the repeated violation of social norms in various contexts, which can entail physical or emotional hostility towards others, disrespect for authority and unlawful conduct (Bartol & Bartol, 2015; Maruschi, Estevão, & Bazon, 2014; Murray, Cerqueira, & Kahn, 2013; Souza & Resende, 2016; Ward & Williams, 2014). Brazilian legislation holds juveniles responsible for delinquency by way of socioeducational (correctional) measures in Juvenile Court (Law no. 8069 - Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente - ECA [Child and Youth Statute], 1990). Such measures range from the most lenient (warnings) to the severest (liberty deprivation). Although the expression incarceration is internationally recognized, Brazilian authors prefer the term "liberty deprivation" to emphasize the more educational purpose of this measure. For this reason, the term "liberty deprivation" will be adopted in this manuscript. The ECA refers to juvenile offenders as "adolescents that are in conflict with the law," and their unlawful acts are called "offenses," not "crimes." In Brazil, such socioeducational measures are based on the doctrine of full protection. This doctrine establishes shared responsibility, among the family, society and the government, so as to guarantee adolescents' fundamental rights. Ultimately, socioeducational measures aim at reeducating adolescents that are in conflict with the law and restructuring their lives so that antisocial and delinquent behaviors are not repeated. In this sense, such measures primarily seek to educate the adolescent, with the punitive aspect amounting to a secondary objective (Gobbo & Muller, 2011).

Despite such shared responsibility and notwithstanding the public policies that target juvenile offenders one observes, on the part of programs for implementing such measures, an inability to achieve the objectives of reeducating adolescents and of restructuring their lives (Gobbo & Muller, 2011; Monte, Sampaio, Rosa, & Barbosa, 2011; Oliveira et al., 2016; Zappe et al., 2015). Apparently, full protection is firmly established in the legal field, yet practically applying it is still a challenge (Amin, 2013; Assis, 2006).

Predominant among juvenile offenders, and especially those deprived of their freedom, deficiency and failure have been considered risk factors for the development of antisocial behavior (Assis & Constantino, 2005; Bazon, Silva, & Ferrari, 2013; Dantas, 2014; Gallo & Williams, 2008; Lochner, 1999; Murray & Farrington, 2010; Nardi & Dell'Aglio, 2010; National Justice Council [CNJ], 2012; Padovani & Ristum, 2013; Sander et al., 2011). Silva and Bazon (2015) contended that the school significantly influences the student's conduct - by way of its organizational structure, institutional atmosphere and practices - and they identified poor performance, antagonistic relationships with peers and teachers, and frequent severe school punishments as factors that are associated with unlawful behavior. According to the above authors, poor performance could contribute to weakening the student's ties with the school, leading to his/her rejection and exclusion by peers and teachers. Frustration in relation to one's ability to learn and poor personal relationships with classmates and teachers have a negative effect on both performance and social behavior, increasing the student's chances of being punished, which further weakens his/her ties with the school. In the long term, discouraged students give up their studies, paving the way for early employment or involvement in delinquent acts. The authors advocate both prevention and effective treatment in relation to young people's involvement in delinquent acts, recommending initiatives that reinforce the adolescent's socialization process and promote their personal and social development.

In Brazil, the National Justice Council's report entitled "Relatório Panorama Nacional - A Execução das Medidas Socioeducativas de Internação" [roughly translated as National Overview of the Implementation of Correctional Detention Measures] (CNJ, 2012) indicated that 8% of the adolescents detained at a correctional facility were illiterate. Furthermore, 57% were not attending school prior to confinement at the facility and 86% had not completed elementary schooling, having abandoned their studies during grade school. Although deficiency does not explain the complexity of the emergence of antisocial behavior (Casey, 2011; Fernandes, 2014; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), the report's statistics strengthen the view that a low education level is associated with both greater vulnerability and the emergence of antisocial behavior and delinquent conduct.

In the Brazilian system of implementing correctional measures, the schooling varies according to the program in which the adolescent is placed. Juvenile offenders serving a sentence of non-custodial or semi-custodial correctional measures are enrolled in public schools of the state-run school district, receiving traditional schooling. In contrast, juvenile offenders receive education that is adapted to the system, in the form of group classes that follow the ordinary sequence of conventional elementary and middle school grades.

The law stipulates specialized instruction, with schooling being mandatory, aiming to balance the punishment dimension of social education (liberty deprivation) with the ethical-pedagogical dimension. Unfortunately, the adolescents serving time in juvenile correctional facilities (detention centers) face a reality that is detached from the legal ideal. Studies reveal the ineffectiveness of schooling at Brazilian correctional facilities due to the precarious physical, material and structural conditions of the places where classes are given; the lack of qualified teachers with specialized training for dealing with juvenile offenders; the lack of a Pedagogical Political Project and of liaison between state boards of education and such facilities; the difficulty involved in balancing the disciplinary and ethical-pedagogical aspects of the intervention proposed for juveniles in liberty deprivation; the teachers' difficulties in dealing with the cognitive, emotional and experiential limitations of youths receiving social reeducation; and perpetuation of the notion of punishment, favoring security standards, to the detriment of educational activities (Dantas, 2014; Ferreira, 2015; Gualberto, 2011; Oliveira, Voltolini, & Costa, 2016; Padovani & Ristum; 2013).

Zanella (2010) pointed out the challenges and contradictions involved in the inclusion of juveniles, especially delinquent teens, whose background often amounts to abandonment or evasion of or lack of interest in school. The situations presented by the author are analyzed based on the study of information collected during approximately five years of work in the areas of education and social education.

Despite the shortcomings mentioned above, many institutionalized juvenile offenders pass on to the next grade level without being prepared for it; that is, the accumulated gaps in their knowledge are not compensated for, yet they are promoted to the next grade without having assimilated the skills and knowledge required to keep up with the next school year's curriculum (Bazon et al., 2013; Conceição, 2015).

Deficiencies in institutionalized adolescents also occur in other countries. In the United Kingdom, Hayden (2008) observed that the education of young offenders was severely impaired prior to going to court, with little likelihood of them achieving sufficient progress to qualify them to gain access to further qualifications. The author studied 29 juvenile offenders that participated in an intervention program for reducing delinquent behavior. The program's duration depended on their progress in areas such as reading, writing and math and on their conduct at the institution. By the end of the intervention, three adolescents quit the program and 20 others (69%) were booked for new infractions by the police. The author believed there was a lack of individual support for the participants on the part of the adults administering the program because they did not monitor the adolescents to the extent necessary to resolve their difficulties and vulnerabilities. Despite the low effectiveness of educational programs for institutionalized juveniles, American adolescents consider schooling a positive experience because of the opportunity it provides them to obtain a high school diploma and increase their academic abilities (Unruh, Povenmire-Kirk, & Yamamoto, 2009).

On the other hand, there are reports of positive experiences in relation to compensating for deficiencies by way of intensively applied, individualized treatment programs that respect each individual's peculiarities and difficulties. Gomide, Mascarenhas, and Rocha (2017) assessed juveniles in residential placement who were subjected to individualized special classes together with a series of other interventions for reducing antisocial behavior. Initially, the eight participants exhibited an average of four years of educational lag, which was measured via the School Performance Test - SPT (Stein, 2011). Subsequent to the intervention, the participants' educational lag had decreased from 4.1 to 2.7 years, demonstrating the relevance of the intervention conducted with this population.

Wexler, Pyle, Flower, Williams, and Cole (2014) performed a systematic review of academic interventions (literacy, math and writing) involving adolescents in correctional facilities in the United States. The authors reviewed 16 studies conducted between 1970 and 2012, with a total of 586 participants. Although such studies exhibited methodological shortcomings that impeded the assessment or comparison of the results, the authors believed it was important to stress the potential of implementing effective interventions in this area in order to facilitate the juveniles' successful transition back to society subsequent to being released from the facilities.

Brazilian researchers analyzed the profile of teachers that work in social education for juvenile offenders, discussing the possible reasons for animosity between the adolescents and the teachers (Cella & Camargo, 2009); the influence of personal experiences and deficiencies on the practice of the profession (Cunha & Dazzani, 2016); and the teachers' likelihood of preventing or reducing recidivism (Padovani & Ristum, 2013). Such studies deal with the relationship between the school and the adolescent offender, yet they do not assess interventions involving this population. Accordingly, assessing academic skills programs for juvenile offenders is a necessity for this specific area of knowledge.

Method

Research Design

The present research is a case-control, quasi-experimental study of a quantitative nature.

Participants

The study enjoyed the participation of 18 male adolescents residing in a juvenile correctional facility. They were selected and then divided into two groups (experimental and control), with nine participants in each group. The sample was chosen by convenience, with the inclusion criterion being a minimum of six months of residence in the facility, bearing in mind that the period for implementing the program would last from four to five months in order to administer the pre- and post-tests and conduct the intervention.

The experimental group's participants, among those who were available, were included because they exhibited considerable academic deficiency, with difficulties in reading and writing. They were given an educational program concurrently with the schooling program provided by the Center for Social Education - CSE. The control group's participants were included because they were available for pre- and post-testing, independent of their situation. They participated exclusively in activities offered by the CSE.

At the time of the first assessment, for both groups, the minimum and maximum ages of the participants were 15 and 17 years, respectively; the average age of the experimental group's participants was 16.33 years (Median [Md] = 16; SD = 0.50); and that of the control group's participants was 16.44 years (Md = 17; SD = 1.01). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups with respect to this variable (U = 36.000; p = .730). Most of the participants were not attending school while in custody. The experimental-group participants' average length of schooling was six years (Md = 6.00; SD = 0.87); based on their age, they were expected to have approximately 10.22 years of study (Md = 10.00; SD = 0.87). The mean of real lag measured by the SPT was 8.44 years (Md = 8.00; SD = 1.24). The control-group participants' average length of schooling was six years (Md = 6.00; SD = 1.00); based on their age, they were expected to have 10.56 years of study (Md = 11.00; SD = 0.87), with the real lag average being 8.89 years (Md = 9.00; SD = 1.97). The Mann-Whitney test of the initial assessment indicated no differences for these schooling variables, taking into consideration the current schooling level (U = 39.00; p = .931), the lag in relation to the expected schooling level (U = 22.00; p = .222) and the real lag (U = 33.00; p = .546).

The offenses that determined the correc-tional measure of liberty deprivation were theft (38.9%), homicide (22.2%), armed robbery (22.2%) and drug trafficking (16.7%). A total of 77.7% (14) of the sample's participants were repeat offenders, six from the experimental group and eight from the control group.

Instruments

The School Performance Test - SPT (Stein, 2011) was the principal instrument for assessing the intervention's effectiveness, being administered as a pretest and post-test. The instrument measures each participant's schooling level in terms of his basic academic skills. It involves the following tasks: (a) reading individual words; (b) writing dictated words, featuring dictation both of the words themselves and of sentences included for the purpose of context identification; and (c) performing mathematical calculations, solving both verbally stated and written math problems (Knijnik, Giacomoni, & Stein, 2013). By way of the instrument, we were able to identify which developmental areas were deficient or satisfactory for each adolescent and assess his/her post-intervention progress.

General Procedures

Location, Context and Logistics. The present study was conducted at the CSE of a midsize city in the state of Paraná, one of the states in Brazil's southern region. The CSE is responsible for the implementation of socioeducational measures involving liberty deprivation, which are applied by a court to juvenile offenders from the region.

Initially, we held meetings with the center's staff (coordinators, psychologists, social workers, guards) and teachers in order to explain the intervention and request logistic support for conducting our activities. The staff designated recently admitted adolescents who would be staying at the facility for at least six months. The center's administration authorized the adaptation of two small rooms for conducting the activities and the installation of blackboards and school desks. Together with the administration, we established the activity schedule, selecting two days of the week for the sessions of the educational intervention. On the scheduled days, after security procedures, the researchers asked the center's social works to send the participants to the aforementioned classrooms. The intervention sessions were conducted by the study's first author and a volunteer educator.

Assessment. The STP was administered by research assistants (trained psychology specialists) in a room designated by the facility's administration, lasting an average of one hour for each pretest and each post-test. It was given in the form of individual interviews, in such a way that, for each task, in addition to reading the instructions, we asked the adolescent to provide an example that would enable the evaluator to assess the subject's comprehension of the explanation of the task.

Intervention. The intervention was conducted according to the following guidelines: (a) duration of three to four months, with individual learning support lessons once or twice a week, amounting to 18 two-hour sessions; (b) emphasis on Portuguese and math, with exercises and questions always stemming from a fable read aloud; and (c) development of four standardized course plans, for the initial phases of elementary schooling, subdivided into four levels: for illiterates (level 1); for first and second graders (level 2); for third and fourth graders (level 3): and for fifth and sixth graders (level 4). The school supplies for each participant of the experimental group consisted of a briefcase-type plastic file folder containing notebooks for Portuguese, math, handwriting and drawing; a ruler, a 12-box of colored pencils and a 12-box of colored markers; and a pouch-type pencil box containing blue and black ballpoint pens, two pencils, an eraser, a pencil sharpener, a tube of liquid glue and a pair of school scissors. The supplies were approved by both the facility's administration and the social educators and were returned to the facility's educators at the end of the sessions. The experimental group's participants received their activity folders at the time they left the detention center. The researchers awaited each participant, for the individual session, in the classrooms. The adolescents were searched before and after the activities. At the end of each session, each adolescent returned to his dorm, escorted by the staff.

At the first session, the program's procedure, structure and objective were explained. For all of the sessions, individual file cards were filled out with information concerning the intervention. The sessions began with the reading of a fable, which was read by either the adolescent or the researcher, depending upon the adolescent's schooling level. The participants were encouraged to read while paying attention to punctuation marks. Next, unfamiliar words were marked, with the help of a dictionary, and then interpretation of the fable began, via questions and answers, finally arriving at the moral of the story and encouraging the participant to identify it and the lessons that could be learned from the fable. Subsequently, grammar exercises were done, aiming at teaching or improving the participant's writing of sentences and short texts. At the end of the session, math exercises were performed, associating the activities with the participant's experience, encouraging the participant and helping him/her with difficulties. The adolescents' performance and difficulties during the session were registered on individual file cards, serving as a guideline for the next session's activities. For example, we made notes as to whether the participant (a) discovered the fable's moral by himself; (b) experienced difficulty while reading; (c) exhibited aptitude for a certain mathematical operation or concept; or (d) refused to perform any of the activities. The intervention lasted four to five months. Three participants were released on probation with formal supervision, continuing their participation in the intervention program as free individuals and receiving transportation allowances for commuting to and from the sessions. Four participants attended two sessions a week, while the other participants attended one weekly session alone, due to restrictions related to the facility's activity schedule. Despite such alterations, the protocol previously established for the experimental group was fulfilled by all of the participants.

Ethical Procedures. The present study was authorized by the Juvenile Court responsible for decisions related to the implementation of the correctional detention measure that was applied to the adolescents and by the Justice Department of the state of Paraná, which is the agency responsible for the CSE. It was also approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Paranaense de Otorrinolaringologia, by way of decision no. 50251115.6.0000.5529. Participation in the intervention was voluntary and confidential, and no remuneration was offered. The informed consent form explaining the program, its objectives and the instruments that were to be employed was read and signed by the adolescents and by the institution that legally holds them in custody.

Data Analysis

We first performed a descriptive analysis of each of the groups, followed by inferences as to changes in the performance measured by the STP scores as a whole and separately for each skill that was assessed (reading, writing and math). We then made nonparametric comparisons between the pretest and post-test for each group via the Wilcoxon test (experimental group pretest vs. post-test; and control group pretest vs. post-test) and comparisons between the groups themselves at each moment via the Mann-Whitney test (experimental vs. control group pretest; and experimental vs. control group post-test). With respect to statistical significance, we adopted a P value of less than or equal to .05. Calculated via the STP, the educational lag of the two groups was also compared. Each participant's educational lag was obtained by subtracting the expected school age based on the chronological age from the age attributed by the STP test score.

Results

We analyzed the data from four months of individualized intervention adjusted for each institutionalized adolescent. First of all, with respect to the pretest, we observed no statistically significant differences between the groups for any of the variables in the STP (see Table 1).

Table 1 demonstrates that, despite the fact that the initial selection of the experimental group favored adolescents with greater problems, as indicated by the team, the results reveal no statistically significant differences prior to beginning the assessment. Subsequent to the initial assessment, the experimental group alone participated in the intervention involving one or two two-hour learning support sessions per week, with emphasis on writing, math and reading. A standardized course plan served as a guideline for the activity, although it was adapted to each adolescent's particular needs. The results of this intervention can be seen in Table 2.

The results of the post-test assessment (Table 2) reveal that, subsequent to the intervention, the experimental group achieved scores that were very similar to those of the control group, except in relation to math skills, the comparative data of which demonstrate a tendency toward statistical significance, with clearly superior performance on the part of the experimental group, for the learning support lessons.

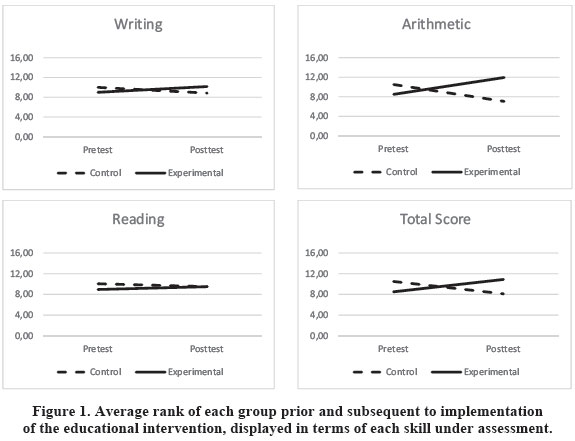

In addition to comparing the two groups' post-test performance, it is worth assessing the experimental group's improvement in performance in relation to its initial assessment, which is also a result of the intervention. To do this, we performed the Wilcoxon test for each of the STP's variables in its specific group. The results revealed that, in the control group, there were no significant changes in writing (Z = -1.62; p = .107), in math (Z = -0.356; p = .722), in reading (Z = 1.487; p = .137) or in the overall score (Z = -1.599; p = .110). In contrast, the experimental group exhibited significant improvements in performance when compared to itself in math skills (Z = -2.673; p = .008), in reading (Z = -1.963, p = .050) and in the overall score (Z = -2.549; p = .011), with a tendency toward significance in relation to writing skills (Z = -1.866; p = .062). In order to facilitate one's comprehension of these statistics, we chose to display the average rank of each group in the pre- and post-test assessments, as can be observed in Figure 1.

The data exhibited in Figure 1 enable one to observe the experimental group's improvement in most of the STP variables in relation to the average rank; and relative stability, and even a decrease, in the control group's math skills and overall score. Such improvements are further evidence of the program's effectiveness. One may thus raise the hypothesis that, if the program were extended for four more months, the differences would be even more pronounced.

Finally, calculated via the STP, the average educational lag at the time of the pretests was 8.3 years for the experimental group and 8.9 years for the control group. Subsequent to the learning support lessons, the average educational lag measured by the STP was 7.3 years for the experimental group and 8.6 years for the control group.

Discussion

The present study sought to assess an educational intervention's influence on a group of adolescents serving time pursuant to a sentence of correctional detention. The study's results indicated a significant improvement in math and reading skills and in the overall STP score when compared to the baseline level. Furthermore, the improvement in math skills stood out, and the experimental group's improvement in performance was significantly superior to that of the control group. Considering the study's logistical problems and, above all, the smallness of the sample, such results seem promising. Moreover, subsequent to 18 sessions of individual instruction (approximately four months), a decrease from 8.3 to 7.3 years of educational lag was observed in the experimental group. The results of the present intervention are consistent with those of studies conducted by other researchers in the area of interventions involving institutionalized youths (Gomide et al., 2017; Joly & Piovezan, 2012; Wexler et al., 2014).

Our decision to employ individual sessions was based on the literature on the subject of juvenile offenders in liberty deprivation (Cole, 2001; Wexler et al., 2014). Such studies indicate that interventions are only beneficial when they target the student's specific needs since conventional activities generally do not work out for this population. Various studies stress that increased schooling is a protective factor with respect to antisocial behavior (Casey, 2011; Gomide, Ropelato, & Alves, 2006; Matos, Martins, Jesus, & Viseu, 2015; Silva & Bazon, 2015; Silva, Cianflone, & Bazon, 2016). In a meta-analysis of 18 studies concerning the role of prison education aimed at rehabilitating adult inmates, Ellison, Szifris, Horan, and Fox (2017) indicated that participating in educational activities reduces the probability of recidivism by approximately one-third, while producing a 24% increase in the inmate's likelihood of finding a job.

A further advantage of the kind of inter-vention that was implemented in the present study is that, in order to conduct this type of activity, one needs no specific academic training in the area of pedagogy. All that is needed by those who conduct such activities is an adequate schooling level and training in the activities that apply to each student's educational level. Nonetheless, what is essential is sensitivity to adapt the intervention's objectives to the needs and peculiarities of the adolescent. Such skills are listed in studies conducted by Stelko-Pereira and Williams (2013), where they describe the abilities a teacher needs in order to enjoy a good relationship with the students and the consequent possibility of helping them with their difficulties. No differences based on the individual conducting the intervention were observed, neither in relation to discipline, respect and the relationship nor in relation to the results of the intervention, a fact that substantiates the notion that the relationship between the educator and the student is a factor that is essential to learning (Monte et al., 2011; Silva, Cruz, & Silva, 2015).

The present study's limitations essentially refer to those observed in field studies: a lack of support for the intervention on the part of some of the staff due to disbelief in the intervention's effectiveness; transmission of incorrect information, leading to delays and overlapping of activities; and erroneous statements as to the length of the adolescents' detention at the facility, which resulted in their release prior to the conclusion of the intervention. Exclusively pre-intervention meetings with the staff apparently were insufficient to raise support for conducting the study. Initially, during the planning phase, the present study anticipated the participation of 40 adolescents, 20 in each group. Nonetheless, due to erroneous information, we lost some of the participants, either because they were released prior to the stated period or because of time slots that coincided with the facility's own activities (during the planning phase, those participants were available). Consequently, the results we obtained with fewer participants only permit limited generalizations. Studies involving larger samples are thus extremely necessary.

According to Walker, Ramsey, and Gresham (2004), schooling can play an important role when it avoids or compensates for the impact of exposure to risk, through the development of social resilience and basic skills and by making emotional support available. As stated by Polleto and Koller (2011a, 2011b) learning math, reading and writing can act as a protective factor for adolescents living with their parents and in shelters that manifest negative emotions and antisocial behavior, reducing the likelihood of repeated delinquent conduct and encouraging personal and social development, to the extent that a better academic repertoire signifies the use of better strategies for dealing with unfavorable, stressful conditions.

In this sense, the implementation of socio-educational strategies that result in reduced educational lag and, consequently, greater opportunities for juvenile offenders appears to be a promising path. It remains, therefore, that this space could be used more opportunely for this purpose.

References

Amin, A. R. (2013). Doutrina da proteção integral. In K. R. F. A. Maciel (Ed.), Curso de direito da criança e do adolescente: Aspectos teóricos e práticos (pp. 52-57). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Saraiva. [ Links ]

Assis, S. G. D. (2006). Fatores protetivos a adolescentes em conflito com a lei no contexto socioeducativo. Psicologia & Sociedade, 18(3),74-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822006000300011 [ Links ]

Assis, S. G. D., & Constantino, P. (2005). Perspectivas de prevenção da infração juvenil masculina. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 10(1),81-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232005000100014 [ Links ]

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2015). Introduction to forensic Psychology: Research and application (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Bazon, M. R., Silva, J. L., & Ferrari, R. M. (2013). Trajetórias escolares de adolescentes em conflito com a lei. Educação em Revista, 29(2),175-199. doi: 10.1590/S0102-46982013000200008 [ Links ]

Casey, S. (2011). Understanding young offenders: Developmental criminology. The Open Criminology Journal, 4,13-22. doi: 10.2174/1874917801104010013 [ Links ]

Cella, S. M., & Camargo, D. M. P. (2009). Trabalho pedagógico com adolescentes em conflito com a lei: feições da exclusão/inclusão. Educação e Sociedade, 30(106),281-299. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302009000100014 [ Links ]

Cole, B. (2001). Year one of the youthful offender program: A teacher's perspective. Journal of Correctional Education, 52(3),105-107. [ Links ]

Conceição, W. L. D. (2015). Escola e privação de liberdade: Um diálogo em construção. Revista Brasileira Adolescência e Conflitualidade, (9),72-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.17921/2176-5626.%25n9p%25p [ Links ]

Cunha, E. de O., & Dazzani, M. V. M. (2016). School and adolescents in conflict with the law: Revealing the plots of a difficult relationship. Educação em Revista, 32(1),235-259. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698144008 [ Links ]

Dantas, V. A. D. O. (2014). A relação com o saber matemático de adolescentes em cumprimento de medida socioeducativa: Sentidos e significados em um espaço privado de liberdade (Master's thesis, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristovão, SE, Brazil). Retrieved from https://bdtd.ufs.br/bitstream/tede/1918/1/VIVIANE_ANDRADE_OLIVEIRA_DANTAS.pdf em 04/01/2017 [ Links ]

Ellison, M., Szifris, K., Horan, R., & Fox, C. (2017). A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the effectiveness of prison education in reducing recidivism and increasing employment. Probation Journal, 64(2). doi: 10.1177/0264550517699290 [ Links ]

Fernandes, D. P. (2014). Explicando comportamentos socialmente desviantes: Uma análise do modelo da coerção de Patterson (Master's thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil). Retrieved from http://repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/7802 em 02/01/2017 [ Links ]

Ferreira, K. D. M. (2015). Instituições socioeducativas de internação e formação do indivíduo. Revista Brasileira Adolescência e Conflitualidade, 10,21-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.17921/2176-5626.%25n10p%25p [ Links ]

Gallo, A. E., & Williams, L. C. A. (2008). A escola como fator de proteção à conduta infracional de adolescentes. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 38(133),41-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742008000100003 [ Links ]

Gobbo, E., & Muller, C. M. (2011). A prática pedagógica das medidas socioeducativas. Emancipação, 11(2),175-187. doi: 10.5212/Emancipacao.v.11i2.0002 [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C., Mascarenhas, A. B. D., & Rocha, G. V. M. (2017). Avaliação de uma intervenção para redução de comportamentos antissociais e aumento da escolarização em adolescentes de uma instituição de acolhimento. Acta Comportamentalia: Revista Latina de Análisis de Comportamiento, 25(1),25-44. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=274550025002 [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C., Ropelato, R., & Alves, M. P. (2006). A redução da maioridade penal: Questões teóricas e empíricas. Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, 26(4),646-659. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1414-98932006000400011 [ Links ]

Gualberto, J. D. G. G. (2011). Educação escolar de adolescentes em contextos de privação de liberdade: Um estudo de política educacional em escola de centro socioeducativo (Master's thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil). Retrieved from http://www.biblioteca.pucminas.br/teses/Educacao_GualbertoJG_1.pdf em 15/07/2016 [ Links ]

Hayden, C. (2008). Education, schooling and young offenders of secondary school age. Pastoral Care in Education, 26(1),23-31. doi: 10.1080/02643940701848588 [ Links ]

Joly, M. C. R. A., & Piovezan, N. M. (2012). Avaliação do programa informatizado de leitura estratégica para estudantes do ensino fundamental 1. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 22(51), 83-90. doi: 10.1590/S0103-863X2012000100010 [ Links ]

Knijnik, L. F., Giacomoni, C., & Stein, L. M. (2013). Teste de desempenho escolar: Um estudo de levantamento [Test for school achievement: A survey study]. Psico USF, 18(3),407-416. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712013000300007 [ Links ]

Law No. 8069. (1990, July 13). Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente, e dá outras providências. Retrieved from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8069Compilado.htm em 15/07/2016 [ Links ]

Lochner, L. (1999). Education, work, and crime: Theory and evidence. Rochester Center for Economic Research Working Paper, (465). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.208291 [ Links ]

Maruschi, M. C., Estevão, R., & Bazon, M. R. (2014). Conduta infracional na adolescência: Fatores associados e risco de reincidência. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 66(2),82-99. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=229031583007 [ Links ]

Matos, F., Martins, H., Jesus, S. N., & Viseu, J. (2015). Prevenção da violência através da resiliência dos alunos. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 16(1),35-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.15309/15psd160105 [ Links ]

Monte, F. F. C., Sampaio, L. R., Rosa, J. S., Filho, & Barbosa, L. S. (2011). Adolescentes autores de atos infracionais: Psicologia moral e legislação. Revista Psicologia & Sociedade, 23(1),125-134. doi: 10.1590/S0102-71822011000100014 [ Links ]

Murray, J., Cerqueira, D. R. C., & Kahn, T. (2013). Crime and violence in Brazil: Systematic review of time trends, prevalence rates and risk factors. Aggression and violent behavior, 18(5),471-483. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.003 [ Links ]

Murray, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). Risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency: Key findings from longitudinal studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(10),633-642. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501003 [ Links ]

Nardi, F. L., & Dell'Aglio, D. D. (2010). Delinquência juvenil: Uma revisão teórica. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 13(2),69-77. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=229031583007 [ Links ]

National Justice Council. (2012). Panorama Nacional: A Execução das Medidas Socioeducativas de Internação. Retrieved from http://www.cnj.jus.br/images/pesquisas-judiciarias/Publicacoes/panorama_nacional_doj_web.pdf em 17/08/2016 [ Links ]

Oliveira, C. B. E., Oliva, O. B., Arraes, J., Galli, C. Y., Amorim, G., & Souza, L. A. (2016). Socioeducação: Origem, significado e implicações para o atendimento socioeducativo. Psicologia em Estudo, 20(4),575-585. doi: 10.4025/psicolestud.v20i4.28456 [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. V. D., Voltolini, L., & Costa, M. C. L. (2016). Por trás das grades: A educação escolar para adolescentes privados de liberdade. Ensino & Pesquisa - Revista Multidisciplinar de Licenciatura e Formação Docente, 14(01),106-122. Retrieved from http://periodicos.unespar.edu.be/index.php/ensinoepesquisa/article/view/883/530 [ Links ]

Padovani, A. S., & Ristum, M. (2013). A escola como caminho socioeducativo para adolescentes privados de liberdade. Educação e Pesquisa, 39(4),969-984. doi: 10.1590/S1517-97022013005000012 [ Links ]

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial Boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [ Links ]

Polleto, P., & Koller, S. H. (2011a). Resiliência: Uma perspectiva conceitual e histórica. In D. D. Dell'Aglio, S. H. Koller, & M. A. M. Yunes (Eds.), Resiliência e psicologia positiva: Interfaces do risco à proteção (pp. 19-44). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Polleto, M., & Koller, S. H. (2011b). Subjective well-being in socially vulnerable children and adolescents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 24(3),476-484. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722011000300008 [ Links ]

Sander, J. B., Sharkey, J. D., Groomes, A. N., Krumholz, L., Walker, K., & Hsu, J. Y. (2011). Social justice and juvenile offenders: Examples of fairness, respect, and access in education settings. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 21(4),309-337. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2011.620816 [ Links ]

Silva, J. L., & Bazon, M. R. (2015). Revisão sistemática de estudos sobre os aspectos escolares relacionados ao cometimento de delitos. Psicologia em Revista, 21(2),273-292. https://dx.doi.org/10.5752/P.1678-9523.2015v21n2p273 [ Links ]

Silva, J. L. D., Cianflone, A. R. L., & Bazon, M. R. (2016). School bonding of adolescent offenders. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 26(63),91-100. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272663201611 [ Links ]

Silva, M. L., Cruz, V. A., & Silva, F. F. (2015). A dimensão afetiva e sua relevância no processo de ensino-aprendizagem: Uma abordagem sociocognitiva. Revista Eletrônica em Gestão, Educação e Tecnologia Ambiental, 18(4),1303-1311. http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/2236117014045 [ Links ]

Souza, C. C. D., & Resende, A. C. (2016). Profiles of Personality of Adolescents who have Committed Homicide. Psico-USF, 21(1),73-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712016210107 [ Links ]

Stein, L. M. (2011). Teste de desempenho escolar (STP): Manual para aplicação e interpretação. São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Stelko-Pereira, A. C., & Williams, L. C. A. (2013). Intervenções em sala de aula. In L. C. A. Williams & A. C. Stelko-Pereira (Eds.), Violência Nota Zero: Como aprimorar as relações na escola (pp. 148-165). São Carlos, SP: Editora da Universidade Federal de São Carlos. [ Links ]

Unruh, D., Povenmire-Kirk, T., & Yamamoto, S. (2009). Perceived barriers and protective factors of juvenile offenders on their developmental pathway to adulthood. Journal of Correctional Education, 60(3),201-224. [ Links ]

Walker, H. M., Ramsey, E., & Gresham, F. M. (2004). Antisocial behavior in school: Evidence-based practices. Bellmont, CA: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Ward, S., & Williams, J. (2014). Does Juvenile Delinquency Reduce Educational Attainment?. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 12,716-756. doi: 10.1111/jels.12090 [ Links ]

Wexler, J., Pyle, N., Flower, A., Williams, J. L., & Cole, H. (2014). A synthesis of academic interventions for incarcerated adolescents. Review of Educational Research, 84(1),3-46. doi: 10.3102/0034654313499410 [ Links ]

Zanella, M. N. (2010). Adolescente em conflito com a lei e a escola: Uma relação possível? Revista Brasileira Adolescência e Conflitualidade, 3, 4-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.17921/2176-5626.%25n3p%25p [ Links ]

Zappe, J. G., Silva Ferrão, I., Santos, C. R., Silva Silveira, K. S., Costa, L. P., & Siqueira, T. V. (2015). A internação de adolescentes em conflito com a lei: Uma reflexão teórica sobre o sistema socioeducativo brasileiro. Revista Brasileira Adolescência e Conflitualidade, (5)112-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.17921/2176-5626.%25n5p%25p [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Murilo Ricardo Zibetti

Rua Tenente Ary Tarrago, 3095, Apto 901, Torre B

Porto Alegre - RS, Brazil

Phone: (51) 99101-1340

E-mail: mrzibetti@gmail.com

Received: 21/02/2018

1st revision: 16/05/2018

Accepted: 02/06/2018