Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Psicologia Escolar e Educacional

Print version ISSN 1413-8557

Psicol. esc. educ. vol.1 no.2-3 Campinas 1997

ARTIGOS

Affective assessment1

Avaliação da afetividade

Thomas Oakland

University of Florida

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper are to present a taxonomy of affective qualities, to describe basic terms, to discuss principles that help ensure accuracy, to provide examples of methods commonly used to measure affective qualities, and to provide information that may further assist persons seeking more in-depth knowledge of some topics.

Keywords: Test, Measurement, Affective qualities.

RESUMO

O propósito deste trabalho é o de apresentar uma taxonomia de qualidades afetivas, descrever termos básicos, discutir princípios que ajudam a obter precisão, oferecer exemplos de métodos geralmente usados para medir qualidades afetivas e oferecer informações que possam ajudar às pessoas que buscam conhecer mais profundamente estes tópicos.

Palavras-chave: Testes, Medidas, Qualidades afetivas.

Introduction

During its 110-year history, academic and research psychologists have devoted more attention to cognitive qualities than to affective qualities. Emphasis on empirical research which explores and defines theories and concepts of intelligence, achievement, and cognitive aspects of neuropsychology generally have out-weighted similar activities focusing on affective qualities.

For example, Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive objectives (Bloom, 1956) generally is wellknow, has stimulated considerable research interest, and has found numerous applications in education and business. The six components that comprise this taxonomy of cognitive abilities include knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Less familiar is the taxonomy of affective qualities (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia, 1964). These include the following five qualities:

1. to receive (i.e., a person is aware of or passively attending to certain events or stimuli, for example when a child is listening and being attentive to what others are saying),

2. to respond (i.e., a person complies to requests by attending or reacting to certain events or stimuli, for example when a student is obeying class rules, complying with a teacher's requests, and participating in class activities as expected),

3. to value (i.e., a person displays behaviors consistent with one or more beliefs or attitudes in situations where she or he is not forced to comply or obey, for example when a person demonstrates a definite preference or displays a high degree of certainly and conviction as when a child regularly asks to be read to, demonstrates acts of kindness toward others, or saves money on a regular basis),

4. to organize (i.e., a person is committed 10 a set of values and displays or communicates his or her beliefs or values in other ways, for example when a student develops a rationale for why democracy is valued and why its value is higher than others), and

5. to characterization (i.e., a person's total behavior is consistent with the values she or he internalized, -for example when a student displays consistency between his feelings, thoughts, and behaviors).

Definitions

The term affect generally refers to emotions and feelings and is thought to encompass broader qualities that include temperaments, personality, attitudes, and values; these qualities are thought to influence personal interests, likes, perceptions and other qualities. The term is not well defined and often used inconsistently within the behavioral science literature. The term often is used to contrast two other broad and commonly-used terms: cognition, and physical-motor. Although the term may lack specificity and clarity of meaning, the qualities encompassed by it are critical to a complete and accurate understanding of human behavior.

Moreover, attempts to agree upon common terminology to describe instruments and methods that assess affective qualities have not been successful. Although one might think the use of the term test might be suitable, this term often is reserved for use in describing specific methods of assessment that allow one to directly observe the actual performance of persons under standardized conditions. Many of the methods used to assess affective qualities may not provide either direct observations or standardized conditions. Thus, broader terms including self-report, survey, questionnaire, and checklist often are used to describe commonly used methods of affective assessment.

Basic principles that help ensure accuracy

Measurement of important personal and social qualities, including affect, cannot occur directly. Unlike the measurement of height and weight, which involve the use of well calibrated and standardized tools that directly measure stable qualities, the measurement of temperament, personality, attitudes, feelings, emotions, and values may involve the use of tools that are not as well calibrated, may lack norms, and may assess hypothetical constructs which display differences from week to week.

Methods have been developed to help overcome these and other potential difficulties associated with the assessment of affective qualities. Some of the more prominent are discussed below.

Use of multiple procedures

An accurate appraisal of all personal traits and qualities, including cognitive and affective qualities, can be enhanced by using various methods of assessment that draw upon information from various sources in order to assess various traits. The use multiple methods -to acquire information from multiple sources on multiple traits is thought to be especially important in the assessment of affective qualities. Empirical evidence that examines concepts important to affective qualities often is weaker than similar evidence for cognitive qualities. Thus, conceptual definitions of affective qualities often lack clarity and precision. Furthermore, some affective qualities, in contrast to cognitive qualities, are thought to be measured less reliably either because by nature they are more changeable or because measures of affective qualities are less reliable. Each of the three multiple procedures is discussed below.

Use multiple methods

Various methods exist to assist in the collection of information. They include the use of observations, interviews, self-reports, naturalistic inquiries, questionnaires, surveys, and other forms of measures. These methods vary considerable in purpose, cost, procedure, flexibility of use, and clarity of focus. Additional information on these and other methods will be presented below.

Use Multiple Sources

Measurement generally is thought to be enhanced when information from various informed and knowledgeable sources is considered. For example, when working with adolescents, measurement of important affective traits may be enhanced by acquiring information directly from the target adolescents as well as from their parents and siblings, teachers, friends and other peers, together with others who may know them well.

The acquisition of information from others may be particularly beneficial when the traits being measured are displayed externally (as opposed to ones, like preferences, that are displayed internally), the qualities being assessed are less reliable (e.g., moods), and the psychometric properties of the measures are weak. The availability of information from various sources enables professionals to determine its completeness and consistency. In general, information that is more complete as well as consistent between sources is thought to be more valid and reliable.

Assess multiple traits

An accurate understanding of one important trait is enhanced by information about various other important traits. For example, an understanding of qualities associated with extroversionintroversion generally is enhanced by knowledge of a person's age, gender, intelligence, achievement, language, self-concept, and other important personal qualities. This principle, one that stresses the importance of acquiring and integrating a broad base of knowledge to promote an understanding of an individual, is central to Gestalt psychology which holds that a person is more than a sum of her or his parts. An integrated understanding is needed, one provided from an accurate appraisal of various important qualities that are likely to interact and mutually affect one another. (See Appendix A for two case studies that describe this integration).

Affective information may be less reliable

As noted above, some affective qualities, in contrast to cognitive qualities, are thought to be measured less reliably either because by nature they are more changeable or because measures of affective qualities are less reliable. Therefore, in contrast to cognitive measures, information provided by affective measures generally is thought to be less reliable and to have a shorter period of time during which it remains valid and useful.

Examples of methods that measure Affective Qualities exist for use in collecting information on affective qualities. Some of the more commonly used methods are discussed below.

Interviews

Interview methods are some of the oldest and remain the most popular for the collection of affective information. Given their popularity, their range is broad. Interviews may be conducted by a individual, team or panel; may be conducted overtly or covertly; may focus on historical or current qualities; and vary in terms of their structure.

The popularity of interviews is due, in part, to their flexibility and ease of use. Decisions on such issues as their length, the settings in which they occur, the nature and range of topics selected for discussion, and the number of people involved typically are made at the interviewer's discretion.

Despite their popularity and numerous advantages, interviews often are fraught with difficulties. The personal nature of the interview, the range of topics that may be discussed, together with the need to present ones self as exhibiting targeted qualities may create conditions that lessen the accuracy of information. Four brief examples are provided below.

Anxieties felt by interviewees may prevent them from communicating effectively. Persons with extroverted styles generally "perform" better even though they may have qualities that are inferior to those with introverted styles. In addition, personal biases (e.g., age, gender, racial-ethnic) of the interviewer and interviewee may limit their objectivity. Finally, interviews generally do not allow participants to develop feelings of mutual trust, a quality important to an open and honest discussion of issues.

Few professionals are trained or properly prepared to conduct interviews. The belief that interviewing skills are inherent belies the truth as to the difficulties associated with conducting interviews effectively.

Naturalistic inquiry

Naturalistic inquiry utilizes unobtrusive methods to collect information. The term unobtrusive means to make one go unnoticed. Thus, persons using naturalistic inquiry methods to collect information strive to remain as obscure and unnoticed as possible so as to minimize the possibility their inquiry will distort the nature and quality of data they are attempting to collect.

Naturalistic inquiry may involve the collection and use of naturally appearing information. For example, prior medical and school records, art work, letters, notes, schedules of work and leisure time activities, awards, misconduct notices, legal records and other forms of historical information may provide rich resources.

Naturalistic inquiry also may involve stationing one or more persons in settings (e.g., homes, classrooms, work and eating areas) in which the target behaviors of persons can be observed naturally and to record and in other ways acquire information. This form of naturalistic inquiry often is called behavior observation or behavior sampling.

Behavior sampling involves a process of recording the presence or absence of specified target behaviors or other qualities. Time sampling, one form of behavior sampling, refers to methods that record the frequency a target behavior occurs during specified time intervals. For example, one may be interested in the frequency an adult talks with co-workers. An observer, stationed to observe this behavior in an unobtrusive fashion, may record the number of times the target adult talks with co-workers at one, five, ten or fifteen minute intervals. Behaviors that occur frequently may warrant the use of time sampling methods.

However, those behaviors that occur infrequently may warrant the use of event sampling, a second type of behavior sample. In event sampling, a record is made of the number of times a behavior (I.e., an event such as the need to urinate or to consume water) occurs within a larger segment of time (I.e., a class period, a work day). Given the infrequent occurrence of the event, a teacher, supervisor, and in some cases the person himself is given responsibility for recording the number of times the event occurs; the employment of a professional observer for this purpose generally would be too costly.

Naturalistic inquiry, when conducted well, has the important advantage of not manipulating or changing the nature of the person or program being targeted for study. The information it provides may describe target behaviors and qualities highly accurately. Disadvantages associated with using naturalistic inquiry include the following: it can be time-consuming of personnel time and thus costly, the presence of observers may be obtrusive, and the behaviors needed to be observers may not be present.

Standardized self-reports

Various commercially-available measures to assist in the assessment of affective qualities require children, youth or adults to directly respond to items. These self-reports include measures of temperament, personality, attitudes, interests, feelings, values, and problem behaviors. These scales require respondents to record their responses to words or questions (see Table 1 for two examples).

Many of the qualities assessed by self-reports are internalized, qualities not readily known to others. For example, when assessing personal preferences, persons may reveal preferences that are inconsistent with their current behavior. Whereas others may disagree with the assessment results because the results do not reflect the behaviors they observe the person displays, only the person who completed the measure can determine the accuracy of the results, given the personal nature of the assessment.

Self-reports that assess externalized qualities (I.e., those openly and commonly displayed through one's lifestyles) may be completed by the target person as well as by others who know her or him well.

Standardized self-reports offer numerous advantages. They generally provide norms and thus offer a normative basis for comparisons, their psychometric properties generally are known, they can be conveniently administered and scored, and they often are readily available. Disadvantages include costs associated with their initial purchase, the narrow range of qualities they may assess, and their lack of availability in many developing countries.

Furthermore, their use is limited to persons whose language and reading abilities are sufficiently developed and who have sufficient self-awareness so as to report their feelings and thoughts in a valid fashion.

Unstandardized self-reports

Researchers and practitioners often develop their own surveys of affective qualities, in part to overcome some of the disadvantages associated with the use of standardized surveys as noted in the previous two sentences. These scales often are tailor-made to assess a specific and narrow range of qualities thought to reflect affective qualities of special interest to the test developers.

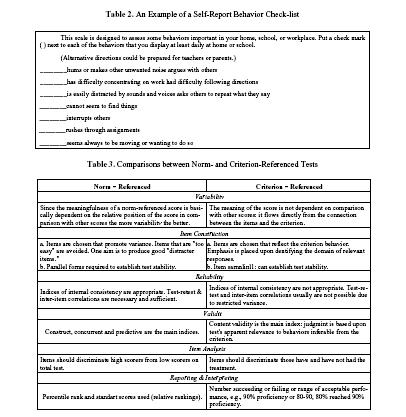

Checklists, a particular form of self-reports, ask persons to indicated whether they or others demonstrate a set of qualities or behaviors. For example, checklists are used commonly to assess difficulties in attention, concentration, and hyperactivity exhibited by students (see Table 2 for an example). A checklist may ask respondents to indicate whether the behaviors appear (I.e., yes or no) or the degree of their appearance using a Likert scale.

A Likert scale requires respondents to distinguish degrees to which various behaviors are present. For example, a scale designed to assess problems with concentration, attention and hyperactivity may ask respondents to indicated whether the target person hums or makes other unwanted noise using the following 5-point scale:

Responses to 20 or more different items measuring the same behaviors may be summed. Scores ranging from 20 through 100 may be, interpreted in two ways.

The data may be used in a manner consistent with criterion-referenced assessment in which a person's score is compared against a standard arbitrarily agreed upon as being suitable. For example, using a range of scores from 20 to 100, professionals may decide that persons with scores below 35 warrant special interventions.

Alternatively, the data may be used in a manner consistent with norm-referenced assessment in which the person's scores are compared with those from others of similar age and gender (see Table 3 for comparisons between criterion-referenced and norm-referenced assessment).

The development and use of unstandardized measures of affective qualities offer a number of advantages including minimizing costs, targeting specific and important qualities, and tailoring items and other test qualities to the characteristics of the respondents (e.g., cultural, age, cognitive). However, the apparent advantages they may provide generally are over-shadowed by their inadequate psychometric qualities, flaws often not readily seen to most yet potentially fatal. Furthermore, personnel time associated with their development may be prohibitive.

Sociometric methods

As previously noted, information provided from peers may enhance one's understanding of important affective qualities that impact social relationships, self-concept, and other feelings of acceptance and adequacy. When sociograms are used, persons who comprise a particular social group (e.g.., a class, team, or work group) are asked to indicate the names of others in the group who they believe embody a particular quality. For example, children may be asked to nominate three classmates who they (I) would like as their friend, (2) would ask for help when they have a problem, (3) would want to serve as the leader, or (4) feel is too demanding or obnoxious.

Sociograms offer a unique perspective by capturing selected opinions peers have about one another. Information can be useful in forming groups, in identifying those who may be leaders or isolates socially, and in evaluating treatment effects (e.g., the effects of social skills training on isolated students). Disadvantages include the possibility of drawing attention to and offending those are isolated or negatively rated and not knowing the reasons why persons who are nominated display targeted qualities.

Case Studies

Case studies involve in-depth reviews of various traits acquired from various sources thought the use of various methods. They may provide a thorough analysis of qualities thought to impede a person's development (e.g., intelligence, language, visual and auditory perception, personality and temperament, learning and study strategies). Case studies often are initiated when persons become involved with legal authorities or are being considered for special services within industry, schools, mental health clinics, psychiatric, or other settings. (Readers again are referred to Appendix A for examples of two brief case studies.)

Case studies provide an integration of information for purpose of fully describing behaviors, understanding their development, identifying strengths and weaknesses in their development, arriving at diagnoses, initiating treatments, and providing a baseline for use in determining later changes. The importance of these benefits must be weighted against the significant costs associated with this extensive and detailed work performed by many highly paid professionals.

Conclusion

The assessment of affective qualities becomes critical to a complete and accurate understanding of human behavior. Various methods exist to assist in its assessment. Some of the more prominent methods were reviewed. The wise selection and judicial use of affective measures will help ensure information they provide is reliable, valid, and complement information on other important personal qualities.

Referências

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.) (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The cIassification of educational goals. Handbook I. Cognitive domain. New York: McKay. [ Links ]

Krathwohl, D. R., BIoom, B.S. & Masia,B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 2. Affective domain. New York: McKay. [ Links ]

1 Apresentado no III CONPE, Rio de Janeiro, 1997.

Appendix A: Two Case Studies

Case I: Shannon

Reasons for Referral: underachievement, defiant, inappropriate conduct

Shannon, an 8 year-old second grader, was referred for assessment due to underachievement as well as several cases of lying and stealing. Her school grades were low, and she told her mother that school was boring.

Shannon's teacher stated that she did not follow the teacher's directions and suggested this was due to listening comprehension problems. Shannon's general intellectual abilities are within the Superior to Very Superior range. The difference between her verbal (Very Superior range) and visual conceptual abilities (High A verage to Superior range) was significant. Shannon's skills in reading, mathematics, science, social studies, and humanities are above average for her age and grade. However, Shannon's scores were below average in spelling, punctuation, and word usage.

Shannon exhibited some problems in her test-taking behaviors. Shannon was overly curious during the test. For example, she insisted on knowing what was printed on the back of the cards, asked how many tasks were involved in each test, and tried to peek at the test booklet to see her scores on particular items. At times, her curiosity became intrusive, as though she did not know (or chose not to respect) the bounds of appropriate behavior in working with na adult. Rather than following directions, she apparently wanted to be in charge.

For example, instead of waiting for the examiner to show her the example on several subtests, Shannon would start doing the examples on her own. She also objected to being timed, stating the examiner should also time herself for the sake of fairness. In addition, she stated that she did not like closing her eyes when the examiner was setting up puzzle pieces on one subtest. Shannon's behavior during the testing indicated that she showed a preference for independence and had difficulty taking directions from others and respecting their rights.

Shannon's mother also reported that Shannon was quite independent. While she had some friends, she often preferred playing by herself. She was able to play or work by herself for long periods of time.

A measure of temperament revealed Shannon prefers an introverted-practical-thinkingorganized style, with particularly strong tendencies toward introversion and thinking. These results suggested someone who is self-directed, independent, concerned with fairness, striving to be competent in her work, organized, and structured.

Knowledge of her temperament was quite helpful in understanding her particular behavior patterns. As a child with strong introverted tendencies, she derived energy from being alone rather than with others and thus could entertain herself for long periods of time. In addition; as a child with thinking tendencies, she was unlikely to comply with requests simply for the sake of pleasing others. Rules had to make sense to her in order for her to follow them.

Unfortunately, her desire for self-direction sometimes was seen as stubbornness or reluctance to follow the lead of others. However, Shannon's failure to follow directions was based on her strong need to be independent and self-directed rather than due to a problem with auditory comprehension, as her parents had suspected.

Based on this interpretation of Shannon's behavior, several recommendations were made. First, Shannon was considered for the gifted and talented program at her school. She -was bored with second grade learning tasks and, given her temperament, would most likely do well with more independent learning activities that took into account her individual interests and level of intelligence. Shannon needed help in developing skills in compliance and cooperation with others.

A program was developed to reward her for engaging in cooperative classroom behavior. In addition, given her temperament, explanations were provided to her as to why she must do something rather than expecting her to comply simply to please others. A whole language approach was institutes to help Shannon improve her skills in spelling, punctuation, and word usage. Toward this end, Shannon was encouraged to continue reading books that were of interest to her. In addition, her parents and teacher continued to nurture her interest and enjoyment in written language while not penalizing her for spelling and grammatical errors in her writing.

Case II: Elyse

Reasons for Referral: possible depression

Elyse, a 16 year-old high school junior, was referred for counseling after becoming depressed over a broken relationship. Her temperament profile revealed that she preferred an extrovertedimaginative- feeling-organized style, with particularly strong tendencies toward extroversion and feeling. Previous testing with an intelligence test showed that Elyse's general intelligence was in the High Average to Superior range. She had particularly strong verbal abilities (in the Superior range) while her perceptual-organizational abilities were in the Average range.

A review of Elyse's academic record revealed that she performed well in school. She had been in a program for gifted children from kindergarten through eighth grade and was taking honors classes in high school. Her greatest academic strengths appeared to be in language arts and humanities. She particularly enjoyed art (e.g., photography, art history, painting) and literature. Her weakness seemed to be in writing. She had difficulty organizing her ideas on paper and found that it took her a long time to complete most of her papers. Outside of school, she had worked as a salesperson in a clothing store prior to finding a job as a make-up artist in a large department store. She planned to attend college as an art history major at a local university.

During the first counseling session, Elyse explained that she had not been able to sleep or eat properly since her boyfriend had decided to end their six month relationship. She had been attending school irregularly, cried 3 to 4 times a day, and felt extremely lonely when she was by herself. She felt the desire to talk to others about how she was feeling but often found that they did not understand. Her parents were supportive at first, but when two weeks went by without improvement, they became impatient with her. Elyse reported that her father's advice to "pull herself up by her socks" only made her feel worse.

Elyse believed she felt depressed about the break-up of this relationship because she thought that this particular boy was different from others she had dated. When they first began dating, after having been friends for several months, he revealed much important personal information to Elyse which he said he never had shared with others. This had made Elyse feel very special and strengthened the bond she felt with him. While she had often found herself in the role of confidant with female friends, she had not found this in a romantic relationship. The relationship was quite intense while it lasted. Elyse felt a great deal of empathy for the boy (who had experienced a number of serious family problems) and wanted to be there for him. When he decided that he wanted to date other girls, she was devastated.

Knowledge of Elyse's temperament as revealed by a temperament measure was quite helpful in understanding her reaction to this situation and in suggesting a particular strategy for counseling. Persons with this style generally are empathetic. Personalized relationships are very important to them. Moreover, when others confide in them, they feel special and important. A common mistake they make in relationships is to focus to a much on the needs of others while ignoring their own.

Elyse displayed this pattern in this relationship. When asked if her boyfriend made her happy, she was unsure how to answer. She had been consumed with helping her boyfriend with his problems and did not realize she had overlooked what made her happy.

Those with this style commonly idealize interpersonal relationships. The ups and downs that characterize everyday interaction with others are difficult for them to handle. Elyse had been excited about her relationship with her boyfriend because she thought it was intense, special, and different. The idea of having a relationship which represents such a unique bonding between people is usually quite appealing to persons with this style. However, the reality of most relationships is that they have their good days and their bad days.

Clinical findings suggested that cognitive-behavioral therapy was the most appropriate treatment for Elyse. Being a very strong feeling-oriented person, she needed to rely more on her logical thinking processes to help her deal with her feelings of depression. Because cognitivebehavioral therapy is focused on helping people examine situations from a rational, logical (thinking) perspective, this form of treatment worked very well for her. It provided new perspectives through which to examine her behaviors.

As a bright and highly verbal person, Elyse was able to clearly identify the dysfunctional thought which had fueled her depression, including thoughts that she would never have good relationships and that there had to be something wrong with her for this boy to leave her. Her feelings of depression were alleviated in about three weeks.

Subsequent treatment focused on helping Elyse to concentrate more on what she wanted for herself in relationships and to recognize that finding the ideal relationship was not a realistic goal. Since extroverted youth tend to understand their thoughts best through talking about them, Elyse was encouraged to use her natural extroverted tendencies to talk to friends and others about the ups and downs in their relationships.