Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1414-6975

Psicol. educ. no.31 São Paulo ago. 2010

The person as actor, the actor as person. Personality from a dramaturgical perspective*

A pessoa como ator, o ator como pessoa. A personalidade que deriva da perspectiva dramatúrgica

La persona como actor, el actor como persona. La personalidad que deriva de la perspectiva dramaturga

Karl E. Scheibe

Wesleyan University. E-mail: kscheibe@wesleyan.edu

ABSTRACT

The article starts from the view that one should look at everyday life as a drama, a place where the "actors" act in reality beyond simple predictions. Starting from this premise, the text brings an analysis based on the following questioning: according to the multiple perspectives of drama - what is personality? And how can we understand the attempt of evaluating and describing of personalities from the dramaturgy point of view? These questions are discussed as much as from acting criticism to the performance of some psychologists that for many times ignore just as much all the dramaturgic richness of human beings, as the analysis of personality evaluations in specific social contexts.

Keywords: Personality; dramaturgy; everyday life.

RESUMO

O artigo parte da visão de que se deve olhar a vida cotidiana como um drama, um lugar onde os "atores" atuam na realidade além de mera previsibilidade. Partindo dessa premissa, o texto traz uma análise baseada nos seguintes questionamentos: o que é personalidade segundo as múltiplas perspectivas do drama? E como nós poderíamos entender a tentativa de avaliação ou descrição de personalidades a partir do ponto de vista da dramaturgia? Estas questões são discutidas a partir tanto da crítica à atuação de alguns psicólogos que, muitas vezes, ignoram toda a riqueza dramática dos seres humanos, quanto da análise de avaliações da personalidade em contextos sociais específicos.

Palavras-chave: Personalidade; dramaturgia; cotidiano.

RESUMEN

El artículo parte de la visión de que se debe mirar la vida cotidiana como un drama, un lugar donde los "actores" actúan en la realidad además de mera previsibilidad. Partiendo de esa premisa, el texto trae un análisis basado en los siguientes cuestionamientos: ¿lo que es personalidad según las múltiples perspectivas del drama? - ¿y cómo nosotros podríamos entender el intento de evaluación o descripción de personalidades a partir del punto de vista de la dramaturgia? Estas cuestiones son discutidas a partir tanto de la crítica a la actuación de algunos psicólogos que, muchas veces, ignoran toda la riqueza dramática de los seres humanos, como del análisis de evaluaciones de la personalidad en contextos sociales específicos.

Palabras clave: Personalidad; dramaturgia; cotidiano.

Let us look at everyday life as a drama, where players, through their actions and choices, mold reality out of mere possibility - creating essences out of the arbitrary.1 (Might interpose the conjecture that there are four major concepts in the drama of everyday life. Once these concepts are understood, the rest becomes filling in of detail and extension of applications. 1) The arbitrary becomes essential. 2) The essence of drama is transformation. 3) Drama requires life reciprocation - the notion of circles. And 4) Drama is intelligible only by understanding the box or context within which the action occurs.)

What is personality from the multiple perspectives of drama? And how might we understand the enterprise of assessing or describing personalities from a dramaturgical standpoint?

Personality is performed, enacted - always in a dramatic frame. The person must act in order to be known; the actor must impersonate in order to exist at all - for otherwise the actor is a mere abstraction - an unrealized potential. Personality is of dramatic interest because individuals are different - distinctively suited for some roles more than others. But the assumptions of psychology about consistency of character are different from those of theater. The director Peter Brook says that, "The interest in actors is their capacity for producing unsuspected traits in rehearsal; the disappointment in an actor is when he is true to form" (1968, p. 105). This suggests a divergence in the interests of the psychologist and the dramatist. The psychologist is interested in predictability - in being true to form. The dramatist is interested in lively spontaneity, novelty, surprise, originality - if always within the constraints artistic requirements of a particular production.

Because personality psychologists have ignored the full dramatic richness of human beings, their enterprise has become at once enormously technical and largely irrelevant to important applications in everyday life. The psychology of personality is by no means enjoying current vigorous strength. Robert Hogan (2002) estimates that there are only about 300 active personality researchers in the United States, while few graduate departments offer a specialization in personality. He asserts that the impact of personality studies on the larger intellectual community outside of psychology is small, largely because of self-inflicted wounds, such as the defense of racial or eugenic doctrines and fundamental disagreements about the ways in which traits might be identified and related to human action.

An ideographic psychology of the person was envisaged by Gordon Allport and is represented in Robert White's (1952) Lives in Progress. But the study of different individuals - the singular turns of their stories, their characters, their enactments - has until recently been dwarfed by the study of individual differences, with its nomothetic emphasis on traits, dimensions, or factors. As a historical note, I suggest that Allport is not blameless for the initial failure of an ideographic psychology, for he neglected the intimate connections between personality and drama. He never appreciated, much less assimilated, the lessons of George Herbert Mead on the primacy of the socius in the development of mind and self. Allport was fixed on the proprium, not the socius.2

So despite Allport, personality psychologists, like their experimentalist colleagues, have had universalist pretensions and have had difficulty framing their discussions of lives in historical context. But today Mead is no longer ignored. Reinvigorated studies of lives in historical context are to be found in the works of Sarbin (1986) on narrative psychology, in Bruner's (1990) discussion of Acts of meaning, in Harré (1979) and his ethogenic approach, in McAdams (1992) and a recent spate of other works where the frame of story is employed to develop a psychological understanding of the person.3 If we view personality as performance, to be understood in the context of particular social framings, how might we think of the enterprise of personality assessment?

Drama in personality assessment

I offer the claim that four distinct dramatic frames are exhaustive of all practiced psychological assessment.

Portraiture: It is a truism, but it bears repeating that no one can see their own body or face as others see them. (I enjoy the revelation that God allowed Moses to glimpse his backside, for thus Moses could claim the advantage of seeing something that God could never himself have seen. Isn't it obvious that God's incessant requirement to be noticed and worshiped is just a demand for dramatic ratification? Even God seems insecure and dependent on applause.) Even in a mirror our image is reversed, and the frozen images in portraits and photographs must necessarily lose a dimension of reality. Schopenhauer said that, "... If anything in the world is worth wishing for... it is that a ray of light should fall on the obscurity of our being". This is a central truth. For the individual, this is core of the dramatic interest in the assessment of personality. Our performances are selectively and partially reflected back to us - and thus the social host ratifies our existence and a social identity is established.

Psychologists are quick to detach themselves from the tradition of phrenology that began with Franz Josef Gall in 1822. But aside from establishing the mind firmly in the brain, Gall should be credited with another accomplishment - for he and his disciples first exploited the exciting potential for self-portraiture offered by a form of psychological assessment. Presidents James Garfield and John Tyler had their heads read, as did Daniel Webster, Clara Barton, Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, Oliver Wendall Holmes - and most enthusiastically, Walt Whitman. The 19th Century was a time of enormous flux, with new opportunities present at every hand. What could be more useful than a scientific assessment of one's individual talents and propensities, thereby to provide guidance for a good and successful life?

I suggest that some of the fascination with looking at fMRI pictures derives from just the same dramatic possibilities as those offered 180 years ago by phrenological readings. Annie Murphy Paul has suggested that, "The next time we gape at the moony flow of an MRI scan or marvel at news of another genetic discovery, we may do well to remember the certain faith people once placed in bumps on the head" (Paul, 2004, p. 205). (Note this morning's Hartford Courant article on "Why do they act that way?" -Psychologist David Walsh - about an explanation of erratic behavior of teenagers in terms of an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex.)

Psychological assessment is an extension of the arts of portraiture.4 Just as there is a moment of excitement in seeing how the artist has rendered our countenance or how our photographs came back from the developer, so there is considerable dramatic interest in learning of one's psychological type, or of seeing a profile of test scores and learning of their interpretation. But there are other dramatic uses of these devices beyond the provision of a charming moment of reflection to the self-in-darkness.

Institutional good function: In fact, the first principle of dramatic motivation for psychological testing misses much of the territory. Binet was not trying to provide assessments of intellectual capacities for children. Instead, he gave practical guidance to an educational system about who could and who could not benefit from schooling. Yerkes and Terman were not interested in telling Army recruits something true and useful about their mental abilities. They were trying to aid the selection of able soldiers, though there is scant evidence that their massive program of testing had any positive impact at all on the quality of our military personnel in World War I.5 The able staff of psychologists employed by the Office of Strategic Services in World War II had a practical institutional problem to solve: How to assess and select men in such a way as to maximize the likelihood of their success as intelligence agents (spies) during the war? (OSS Assessment Staff, 1948). Personality portraits emerged from these assessments, to be sure. But these were not meant for the edification of the assessed but rather for purposeful employment by their trainers and masters.

The dramatic appeal of these assessment programs and of all cognate programs in business, government, industry, and academia is that the scientific assessment of persons might vastly increase the efficiency of selection and placement, with substantial payoffs for institutional good function. Certainly the use of psychological assessment has earned a legitimate place of importance as a tool of selection and placement, though misuse and controversy abound.6

Diagnosis of psychopathology: A third and exceedingly dramatic interest for assessment has characteristics in common both with psychological portraiture and institutional good function - the diagnosis of psychopathology. The question for the individual is, "Am I crazy?". The institutional question is, "Is this person mentally competent and able to function in society?". The vast majority of the devices in the psychometrician's armamentarium were developed to answer these questions.7

The Rorschach test, the Thematic Apperception Test, and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory are among the most widely used assessment devices in the world, and all are employed primarily for the diagnosis of psychopathology. For the first two of these tests, the lack of acceptable psychometric indices of reliability or validity has done little to discourage use by clinicians. The reasons for this are dramatic: Getting patients to tell stories in response to inkblots or pictures and then offering interpretations of the stories work to strengthen the clinician's act. These little exchanges help to reinforce what I have elsewhere called "The psychologist's advantage," providing some credibility to the show, and greatly facilitating the verbal flow in the clinical session - thus relieving boredom for patient and clinician alike (Scheibe, 1978).

It was Rorschach's intention to penetrate to the very heart of personality. The detailed portraits that interpreters such as Klopfer could provide were dramatically rich and fascinating, never mind that evidence for the reliability and validity of these portraits is scant. The same can be said of Murray's employment of the TAT. Here is a comment by Paul (2004):

Harry's enthusiastic interpretation of the TAT was the climax, the Grand Finale, of each case presentation meeting at the Clinic,' remembers a former graduate student. 'Harry could astonish us by giving an interpretation of the subject's TAT that was always brilliant - and sometimes may even have been right. As another student put it, Murray 'knew where to find the skeletons.

The MMPI is perhaps less dramatic, and it does have respectable reliability and validity. The updated MMPI is currently the most widely used of all diagnostic tests - employed by some 86% of clinicians, given to some 15 million

people each year (PAUL, 2004). But here too it is helpful to understand personality as performance - for Kroger (1967) and others have demonstrated that personality profiles are influenced appreciably by the dramatic context within which the test is given. A person taking a psychological test is not exempt from the tendency to manage impressions, to present the self in a way that meets the dramatic requirements of the setting.8

The pure search for truth: A fourth dramatic intent must be identified for the enterprise of personality assessment, for the true personologist would not bear to be identified either as a specialized portrait artist nor as a slave to institutional interests, and certainly not as a psychodiagnostician. Rather, the personologist is too pure a spirit for such functional shackles, preferring instead to quest after universal scientific truths about the structure of human personality, its essential and irreducible dimensions. For the past 75 years, factor analysis has been the method of choice for this enterprise, with such devices as the 16PF and the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule emerging as typical tests. The most recent and significant accomplishment of this line of work, of course, is the Big Five test of personality. However, outside the domain of its discovery and a raft of correlational studies, the articulation of the five essential dimensions of human personality has hardly been an earth-shaking event. Instead, from a theatrical point of view, this development is anti-dramatic, or hugely boring. To be sure, the Big Five nomenclature has found its way into introductory psychology texts and is likely to stay there, next to representations of Galenic humors and Eysenck's earlier attempt to reduce the essential dimensionality of human personality to two. I may be wrong, of course. But I think that the Big Five discovery represents a dead end in the history of ideas, even while it deserves proper respect and regard in the museum of such ideas. At best it is, as McAdams (1992) has suggested, a "psychology of the stranger".

Dramatizing assessment

I turn now to a test that has considerably more dramatic appeal. One of the most astonishing success stories in the history of psychological assessment comes not from the factor analytic tradition just described, but rather from an instrument that was developed out of the rich theoretical ideas of Carl Jung about psychological types. I refer, of course, to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator - still a best seller after over 65 years on the market. "It is now, according to its publisher (Consulting Psychologists Press) the world's most popular personality assessment. It has been translated into sixteen languages, and chapters of the Association for Psychological Type have spring up in places from Australia to Korea to South Africa (there are more than two dozen chapters here in the United States" (PAUL, 2004, p. 125). It seems to me that people are as likely to know their MBTI type as they are their astrological sign. A substantial industry has developed about the MBTI - training centers, professional development workshops, personal development seminars and so on. (Not bad for an invention of a Swarthmore housewife, Isabel Myers, who had no formal training in psychology, in statistics, or in test design.) I have heard distinguished scholars within the field of psychological assessment scoff at the MBTI - for its poor factor structure, for its lack of proved validity, for its crude simplicity. But I believe that these critics have failed to appreciate the dramatic appeal of the instrument.

The MBTI is employed in three of the dramatic frames listed above - as portraiture, as a means of advancing institutional good function, and as a search for the inner essence of human personality. Part of the appeal of this particular mirror for the person is that one simply cannot look bad in it. It ignores and does not register features of psychopathology.

In the course of my teaching, I have had frequent occasion to witness the application and interpretation of the MBTI to groups of students by a talented associate. These demonstrations are invariably impressive. Students eagerly adopt the nomenclature - start to think of themselves and others in terms of one of those sixteen types, or perhaps in terms of the four temperaments - SPs, SJ's, NT's, and NF's.

Why is the MBTI so compelling and dramatic?

First, the fundamental premise of the MBTI is that each of us is endowed with unconscious preferences. To establish this idea, students are asked to write their names with their non-dominant hands and to describe the experience. Students may then be asked to clasp their hands in front of them, to clap their hands together, to fold their arms or to cross their legs - then to perform these same activities in their non-preferred mode, right over left instead of left over right etc. All of a sudden, a ray of light is cast on the obscurity of being, as students instantly grasp the idea that they have strong preferences in the ways they do things, and that other preferences, no better or no worse, are present for others in the same room. This discovery is a dramatic moment.

As I have suggested above, the mirror provided by the MBTI is exceptional in its kindliness. You may be crazy or stupid or crude or rude, but such qualities are sublimely unimportant for this mirror. They do not count. Instead, no matter which of the sixteen boxes you happen to fall into, something good is to be said of you. Individuals of the most rare type, the INFJs, are "...great innovators in the field of ideas". Members of the most common type, the ESTPs, are "...friendly, adaptable realists".9 And so on for all sixteen. You cannot lose.

I need now to digress for a moment to describe a technique employed by the Great Dunninger, who was a popular mind-reading performer in the 1940's. Dunninger would ask for a volunteer to come up on stage from his audience. In a gentlemanly maneuver, Dunniger would descend the stairs from the stage to the audience, take the young lady volunteer by the elbow, and whisper courteously in her ear, "Thank you for volunteering. My name's Dunninger. What's yours?". To which the volunteer would reply, in a matching tone, "Mary Clark." Arriving at the microphone, Dunninger would begin by uttering the astonishing claim, "I believe your name is Mary Clark. Have we ever met before?". To which Mary would respond, in all truth, "Yes, that is my name. And no, we haven't met before". The audience in the auditorium, as well the vast radio audience, is thoroughly impressed!

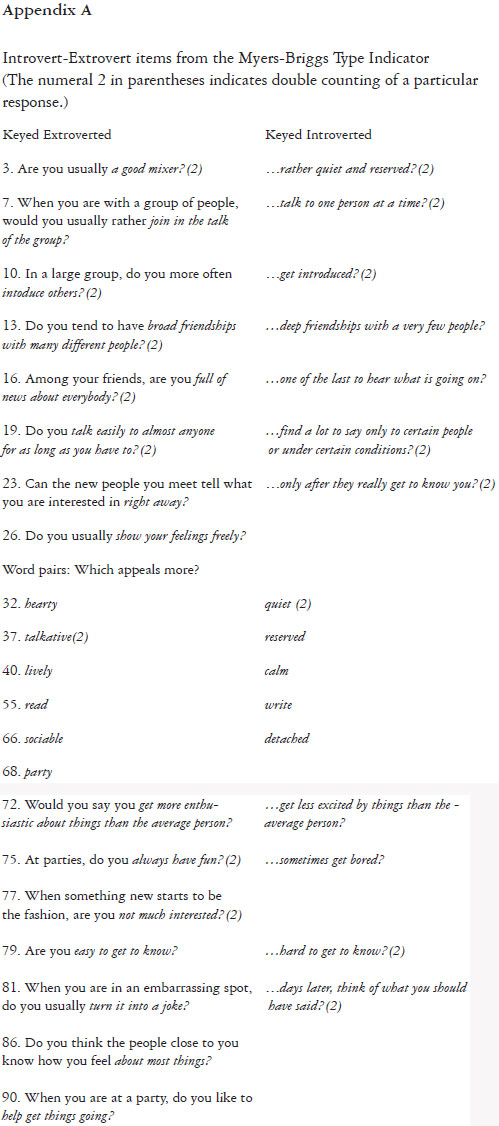

Now back to the Myers-Briggs. I want to make the claim that a similar dramatic device is used in order to reinforce the appeal to validity for the standard four type dimensions. For example, the Extroversion-Introversion items in the test require a person to say whether they prefer "hearty" to "calm" or "talkative" to "reserved." They are asked whether "At parties, do you always have fun?"...or "...sometimes get bored." They are asked, "Are you usually a good mixer" or "rather quiet and reserved." A total of 21 items out of the 126 items on form G of the MBTI are scored for Extroversion-Introversion. (The entire set of items and their scoring is provided in Appendix A.) With double scoring for some items and other transformations, a person ends up with an E-I score than can range over 134 points, from a 67-Extrovert to a 67-Introvert.

Now suppose that the day after the test has been given, with the scoring completed, a group of participants is lined up in rank order of their E-I scores. Suppose further that two extreme groups of five members each are selected from either end of the line thus formed. Then the following task is proposed for the group: "Discuss among yourselves, and later report to the group, your response to this question: How would you use free time?".

The two extreme groups immediately huddle and begin their five-minute discussion. During this time, the leader will take the midrange students aside, and will inform them about what to expect when the groups report back on the results of their deliberations. Then the leader will declare an end to the discussion period and will ask for reports back from the groups, with the Extroverts reporting first, then the Introverts.

True to form, the Extroverts will express their interest in using free time by sponsoring and attending parties and being generally sociable, with an emphasis on talking, playing, dancing, being engaged with others. The Introverts will express their interest in engaging in solitary activities - going for walks, reading, exploring nature, or engaging in individual hobbies or exercise activities. The contrast is remarkable, and for the observing middle group, corresponds exactly to what the leader told them to expect to see. Let no one say that psychologists are incapable of predicting human behavior.

... Particularly, of course, when people have just told you what their preferences are. The show of validity for the Myers-Briggs dimensions proceeds for the other three scales, and no one quite remembers that the responses called for from the contrasting groups match very closely the content of the questions that individuals have answered just a day or two before. The Dunninger demonstration of mind reading and the demonstration of the validity of the MBTI proceed along similar lines. First, privileged information is obtained. Then that information is fed back to an audience in a way that somehow does not reveal how it was obtained. The effect is dramatically impressive, but is rather like sleight-of-hand - where the perception of magic is dependent upon the artful redirection of attention away from what is truly happening.

The standard paper-and-pencil personality inventory can be seen as a device of mystification and obfuscation. Hundreds of questions are asked, and conceptually coherent scales are purposefully randomized in their order. Scoring keys recreate order out of chaos, and result in indices that reveal how the personality is performed on this occasion. The mirror reveals only what it is shown, but the manner of reflection can be dramatically enriched - the more so because the person is likely not to remember very clearly what they just said to the tester.

This helps us to understand why the enterprise of personality assessment can be so popular even though the practical utility such assessment is quite limited. As Kierkegaard observed, "Mundus vult decipi." - the world wants to be deceived.

There is, of course, another reason for the prospering of a dramatic device despite a lack of evidence for its practical utility. The technique of bloodletting was the treatment of choice for a wide range of medical problems for something like 2500 years, up until the beginning of the 20th century. It is what physicians knew how to do. There was a basis in ancient theory - the Galenic theory of humors. And the effects of bloodletting were demonstrably dramatic, if not usually therapeutic. Psychologists know how to do personality testing and we will continue to do what we know how to do. We are better at keeping score than our medical colleagues, to be sure. But still, let us not forget that much of this enterprise is founded on deception and dramatic appeal, and is of marginal functional utility.

In closing, I would like to draw attention to the obvious fact that no casting director in the theater is likely to have any use at all for psychological tests, nor will psychology departments use these devices when they engage in a job search to fill a professorial position. Casting directors know that people are quite distinctive in their capacity to act. The time-honored technique in casting is the audition - where one asks a candidate to read a part, to enact a character. The quality of performance in an audition, together with an actor's résumé and reputation for skill, comprise the criteria for selection. The job talk and attendant performances comprise the academic counterpart of the dramatic audition.

I delight in the discovery of unexpected skills and abilities of my students. I attend an orchestra recital, and there is my teaching assistant playing first violin. I go to a track meet and learn that the student who asked me to supervise his honors thesis is an excellent sprinter. The drama of everyday life is full of surprises - and many of these surprises come from individuals not acting in a way that is true to form. Because personality assessment seems determined to fix individuals into some Procrustean bed of form, its general effect is to reduce dramatic richness rather than to increase it.

Referências

Allport, G.W. (1955). Becoming. Nova Haven, Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Brook, P. (1968). The empty space. Nova York, Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Bruner, J.S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cochran, L. (1986). Portrait & Story. Nova York, Greenwood. [ Links ]

Freeman, M. (1993). Rewriting the self. Londres, Routledge. [ Links ]

Gergen, K.J. (1999). An invitation to social construction. Londres, Sage. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Nova York, Doubleday. [ Links ]

Gould, S.J. (1981). The mismeasure of man. NovaYork, Norton. [ Links ]

Harré, R. (1980). Social being. Totowa, NJ, Littlefield, Adams & Co. [ Links ]

Hogan, R. (2002). Personality and the laws of history. Keynote address, 11th Annual European Conference on Personality. Jena, Germany, July 23, 2002. [ Links ]

Kleinmutz, B. (1967). Personality measurement. Homewood, IL, Dorsey. [ Links ]

Kroger, R.O. (1967). The effects of role demands and test-cue properties upon personality test performance. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 31, pp.304-312. [ Links ]

McAdams, D. (1994). A psychology of the stranger. Psychological Inquiry, 5(2), pp.145-148. [ Links ]

Myers, I.B. & McCaulley, M.H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Links ]

OSS Assessment Staff (1948). Assessment of men. New York, Rinehart. [ Links ]

Paul, A.M (2004). The cult of personality. Nova York, Free Press. [ Links ]

Pillemer, D.B. (1998). Momentous events, vivid memories. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Roberts, B.W. & Hogan, R. (2001). Personality psychology in the workplace. Washington, American Psychological Association Press. [ Links ]

Sarbin, T.R. (1986). Narrative psychology. New York, Praeger. [ Links ]

Scheibe, K.E. (1978). The psychologist's advantage and its nullification. American Psycologist, 33, pp.869-881. [ Links ]

Scheibe, K.E. (2000). The drama of everyday life. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Singer, J.A. & Salovey, P. (1993). The remembered self. Nova York, Free Press. [ Links ]

White, R.W. (1952). Lives in progress. NovaYork, Dryden. [ Links ]

Wood, L.A. & Kroger, R.O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis. Londres, Sage. [ Links ]

* I have had the good fortune of an association with the Educational Psychology program at PUC-SP since 1972. I consider it an honor to be included in this publication honoring the 40 years of the life of that program.

1 This point of view is developed fully in The drama of everyday life (Scheibe, 2000).

2 See Allport's (1955) Becoming.

3 See, for example, Freeman (1993), Mishler (1999), Gergen (1999), Pillemer (1998), Singer & Salovey (1993) and Wood & Kroger (2000).

4 See Cochran, 1986

5 See the discussion in Gould (1981, chapter 5).

6 See Roberts and Hogan (2001).

7 "There are thousands of personality measures in the published literature, and an overwhelming number of them are designed to assess elements of psychopathology" (HOGAN & ROBERTS, 2001, p. 6).

8 The classic reference for self-presentation is Goffman (1959). See Kleinmutz (1967) for a discussion of response sets. (Reference on impression management as well - Tedeschi, Schlenker.)

9 Quotes are from the MBTI manual (MYERS & McCAULLEY, 1985).