Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Boletim - Academia Paulista de Psicologia

Print version ISSN 1415-711X

Bol. - Acad. Paul. Psicol. vol.35 no.89 São Paulo July 2015

THEORIES, RESEARCHES AND CASE STUDIES

Motivations of potential donors to living donor liver

Motivações de potenciais doadores para serem doadores vivos de fígado

Motivaciones de los donantes potenciales a ser donantes vivos de hígado

Ana C. M. StanisciaI,1; Célia Lídia da CostaI,2; Maria Carolina de S. RodriguezI,3Francisco Baptista Assumpção JúniorII,4

IFundação Antonio Prudente

IIInstituto de Psicologia - USP

ABSTRACT

This article aims to evaluate the motivation of donors to Living Liver Transplant (LDLT) related to the numerous dimensions which the potential donor is subjected, such as social environment, relationship to recipient, personal attitudes and benefits they recognize in submitting to such procedure. The interviews were conducted considering socio-demographic data and the potential donors motivations concerning the transplant. Potential donors were a majority of male (52.8%), married (68.2%), with upon Elementary education (36.4%), professionally active (67%); 56,3% did not mentioned religion. Mostly parents donated to children (56.3%); manifest motivations to donation among close relatives was bond kinship (100%), associated motivation was affective predominance with recipient(94%) and internal conflict(6%). Not close relatives or not relatives 72% referred manifest motivation bond kinship; 28% altruistics motivations; as associated motivations 65% related to affective predominance, 35% to identification with recipient (Fisher's exact test, p<0,001). The associated motivation of affective predominance is highlighted by the participants, and is mostly associated to potential donor who has close relatedness with recipient.

Keywords: Living Donor Liver Transplant; potential donor; motivation; psychosocial aspects.

RESUMO

Este artigo tem como objetivo avaliar a motivação dos doadores para Transplante de Fígado Vivo (LDLT) relacionada com as várias dimensões as quais o potencial doador está sujeito, como o ambiente social, a relação com o destinatário, atitudes e benefícios pessoais que eles reconhecem ao se submeterem a tal procedimento. As entrevistas são realizadas considerando-se os dados sóciodemográficos e as motivações dos potenciais doadores relativas ao transplante. Os potenciais doadores são em maioria do sexo masculino (52,8%), casados (68,2%), com educação fundamental (36,4%), profissionalmente ativos (67%); 56,3% não mencionam religião. A maioria dos pais doaram para crianças (56,3%); as motivações manifestadas à doação entre parentes próximos são por vínculo de parentesco (100%), a motivação associada é de predomínio afetivo com o destinatário (94%) e conflito interno (6%). Parentes não próximos ou não parentes 72% referem-se a motivação manifestada por vínculo de parentesco; 28% motivações altruístas; como motivações associadas 65% são relacionados a predominância afetiva, 35% a identificação com o destinatário (Teste de exatidão de Fisher, p <0,001). A motivação associada de predominância afetiva é destacada pelos participantes, e é associada principalmente ao potencial doador que tem parentesco próximo com destinatário.

Palavras-chave: Transplante de Fígado com Doador Vivo; potencial doador; motivação; aspectos psicossociais.

RESUMEN

Este artículo tiene como objetivo evaluar la motivación de los donantes potenciales para ser donantes vivos de hígado Trasplante (DVTH), se refiere a las diversas dimensiones a las que el posible donante se somete, como el entorno social, la relación con el destinatario, actitudes y beneficios personales que reconocieron, al someterse a este procedimiento. Las entrevistas se llevaron a cabo teniendo en cuenta los datos sociodemográficos y las motivaciones potenciales para el trasplante. Los posibles donantes eran la mayoría eran hombres (52,8%), casados (68,2%), con educación primaria (36,4%), profesionalmente activos (67%); y el 56,3% no mencionó la religión. La mayoría de los donantes eran familiares para niños (56,3%); motivaciones expresadas para la donación entre parientes cercanos (100%), la motivación se asoció con la prevalencia de vínculo afectivo con el receptor (94%) y el vínculo en conflicto interno (6%). Pariente no cercanos 72% mencionan el vinculo como la principal motivación; 28% motivos altruistas como la principal motivación y el 65% en relación con la prevalencia afectiva y 35% por la identificación con el destinatario (prueba exacta de Fischer, p <0,001). Los factores motivacionales se asociaron a la predominación afectiva destacada por los participantes, y por lo general se asocia con el donante potencial que tiene estrecha relación con el destinatario.

Palabras clave: Donante Vivo de Trasplante de Hígado, Donante Potencial; motivación; aspectos psicosociales.

Acronyms used in the text: LDLT = Living Donor Liver Transplant; PD = Potential Donor; CNPq = Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Manuscript Introduction

Living liver donation provides a few advantages to the recipient such as assurance of a healthy organ with minimal preservation damage, it helps alleviate the severe shortage of deceased donor livers, and it reduces mortality of patients on the transplant waiting list (Miller, 2008). To achieve benefits of the living donor liver transplant (LDLT), the donor is subjected to risks (Gerken, 2003) which demand further refinements in the psychosocial assessments of donors (Jowsey & Schneekloth, 2008). Therefore, this surgical procedure requires a new level of donor risk tolerance, leading the transplant team to support the donor on his confidence during the decision making process ( Surman, 2003).

On behalf of the potential donor's psychologically evaluation, it's necessary to have concise motivational arguments that offer enough bases to justify the donation, as well as to face any repercussion that this can cause (Papachristou, Walter, Dietrich, Klupp & Klapp, 2004).

The decision to become donor can instigate processes that go beyond donor's control; it is based on emotional process that leads to a spontaneous decision, rather than a cognitive information-guided process (Karliova et al., 2002).

The determinate factors of donor's motivation relates to numerous dimensions in which this potential donor (PD) is subject to, such as social environment, relationship to recipient, their personal attitudes and benefits recognized in submitting to such procedure. Moreover, such dimensions characterize for having its proper dynamic when composing the motivation of the donor, as well as, influencing the attitudes of the family of the recipient and the medical staff (Karliova et al., 2002).

Considering the effectiveness and frequent use of LDLT, little is known concerning the real motivations that describes the act of donating a piece of, or entire organ, to another person (Walter, Brommer, Steinmuller, Klapp & Danzer, 2002; Walter, Ppachristou, Danzer, Klapp & Frommer, 2004). After literature survey we understand that there are very few studies that investigate the characteristics of Brazilian population related to its motivations concerning LDLT. The aim of this study was to analyse referred motivations for the living donor liver transplant and to characterize the potential living donors to the LDLT in accordance to their psychosocial aspects.

Materials and Methods

The PDs of hepatic transplant arrive at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology of the Hospital A. C. Camargo for psychological evaluation, while clinical aspects are still evaluated by the Department of Hepathology in relation to donor's compatibility with the receiver.

The mental health professionals routinely evaluate aspects related to psychiatric and psychological antecedents, psychological/psychiatric state and potential risks for psychological complications after donation, as well as aspects related to donor's quality of life. Based on the performance of candidates in evaluations they are considered to be apt or not apt for hepatic donation.

A psychologist conducted one interview with all potential liver donors when they arrived for hepatic pre-transplant psychological evaluation at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at Hospital A.C Camargo.

The variables investigated in this interview were: conjugality, education, religion, employment status, residence, history of psychiatrics and psychological events, tobaccoism, alcoholism, referring use of drugs, knowledge on the risks and procedures of the transplant, degree of relatedness with the recipient (when the donor and the recipient were not related the length of the relationship was analysed) and motivations concerning the transplant.

The variable "degree of relatedness with the recipient" was in a second moment re-grouped to possibilitate an analyses by the Fischer test, therefore it became composed of two categories: close relatives (mother, father, son) and not close relatives or not relatives (uncles, nephews, cousins, brothers-in-law, grandmothers, friends etc.). The categories were grouped in this way considering the affective bow between the relatives mentioned.

Content analysis is composed of categorization, which consists of the classification of constituent elements of a set occurs, for differentiation and followed by regrouping according to affinities. In the second stage, one produces the association of a focal text to its social context in an objective way ( Bardin, 1997). A content analysis of the interviews conducted in this study resulted in six categories for transplant motivation of potential living donors.

Manifest Motivation was related to what was explicitly said by the donor. What the individual wanted as justification for its act. Manifest motivation can be classified in two categories.

The first called "Bond kinship" was when the motivation had predominance of associated affective bow to the social role; when next relatives were presumable donors. This category consisted of parents whom mainly donate to their children. It could also happen when the giver had affective bow which made the donor feel affectively connected to the recipient "as if he was father or mother". With less frequency it could be related to other degrees of kindred as children donating to parents or brothers donating to brothers. Also the predominance of the affective bow of the individual could occur in a way that the donor felt "as if he was son/ parent" or "as if he was brother" of the recipient.

The second category, called "Altruism", a motivation that does not originate from affective bow, but from the desire to do something good. The bond of kinship was not normally observed and, when this occurred, did not have predominance of the affective bow in the expressed motivation of the individual.

The Associated Motivation was classified after an analysis of what the individual said regarding its relation with the receiver. They appeared exactly from an analysis of the donor's speech, and what the individual said regarding its motivations for the donation. The category "Moral Obligation" included motivations that did not originate from affection when this could be considered to be the expected motivation. It occurred, for example, when the donor had bond of kinship with the recipient but did not have a corresponding affection, besides is morally charged by society that they become available to the donation.

Another category, called "Affective Predominance", was considered when donation motives had a clear affective origin. Normally, it was observed in bond of kinship, but it could also occur in other conditions where relationship existed between the donor and receptor.

A third category, called "Internal Conflict" considered motivations that occurred when there were conflicts between the donor and the receiver, and the donation was an attempt to resolve these conflicts.

Finally the category, "Identification", was when the donor could relate to the situation that the recipient was experiencing. The donor was referred to a difficult situation that he lived and now he associated it with the situation deeply lived by the receiver. The motivation was related to characteristics that the situation of the receiver "made the donor remember", regarding its personal history.

A prospective study was perceived based on evaluations from all 177 PDs received from January 2003 January 2006 at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology of the Hospital A. C. Camargo.

Results

The results have taken into consideration 176 evaluations of PDs of hepatic transplant directed to the consultation-liaison psychiatry and psychology service in the Hospital A. C. Camargo of January of 2003 until January of 2006. One of the PDs refused to finish the interview and was excluded from the data base.

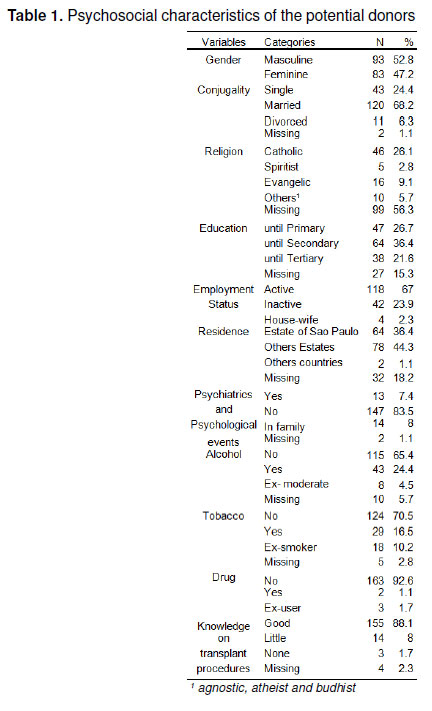

The frequency of psychosocial variables is shown on table 1. Potential donors were a majority of male (52.8%), married (68.2%), with upon Elementary education (36.4%), professionally active (67%); 56.3% did not mentioned religion. Considering the use of alcohol, 65.4% referred not make any use of alcohol; 24.4% referred that were making use of alcohol; 4.5% referred ex-moderate use of alcohol and 5.7% missing. PDs that referred social use of alcohol were 90.6% and 9.4% referred moderate use of alcohol.

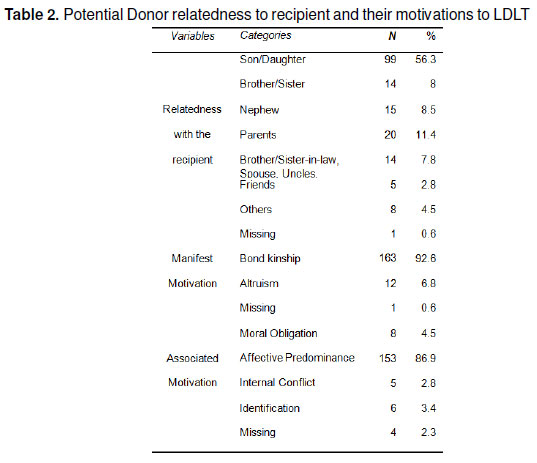

The degree of relatedness with recipient can be observerd on Table 2, 56.3% of PDs wished to contemplate one of his/hers children; 11.4% wanted to donate to one of its parents; 8.5% to a nephew; 8% to any brother or sister; 7.8% to one of his/hers uncle/aunt, spouse, brother/sister - in law, grandchildren or cousin; 4,5% had a recipient who was a known of a friend; 2,8% was PD to a friend and 0,6% there were no register of who was the recipient in our database.

The manifest motivation to LDLT was in 92.6% of bond kinship; 6.8% altruism and there was 0.6% missing. Considering associated motivation to donation 86.9% was of affective predominance; 4.5% moral obligation; 3.4% identification; 2.8% internal conflict and 2.3% there were not enough information on the interview (Table 2).

Using the Accurate of Fischer test we found a correlation between degree of relatedness with recipient and associated motivation variable and manifest motivation variable (p < 0,001). Regarding other associations no statistically significant results was found. Considering close relatives (mother, father, son) and not close relatives or not relatives (uncles, nephews, cousins, brothers-inlaw, grandmothers, friends, friends of friends) as another category of the variable degree of relatedness with recipient: PDs to LDLT contemplating close relatives, had in 100% (n=133) as manifest motivation bond kinship. Considering the motivation identified on PDs discourse, 94% (n=125) referred affective predominance with recipient. Other motivation observed was the 6% (n=8) internal conflict among PD and recipient. In the not close relatives or not relatives category 72% (n=31) referred as manifest motivation bond kinship; and 28% (n=12) mentioned altruistics motivations. Among motivations interpreted from speech of donor, 65% (n=28) related affective predominance and 35% (n=15) motivation was identification with recipient.

Discussion

The findings in PDs donating to close relatives and their manifest and associated motivations were expected as the bond of kinship estimates a strong affective predominance among the PDs and recipients explicited present in donor's discourse. The predominance of its categories is due to the numerous transplant pre-operative evaluations taken between parents, childrens and siblings. Therefore these family relations produce strong affective bond between its members, which are the main influence identified in our study investigating motivation to LDLT.

Other questions have been identified as associated motivation to donate like internal conflict (familiar conflicts) which occurred in 6% of the subjects (n=8). In this category, the donor's motive is to submit their self to transplant as a chance to resolve any existing conflict in the relationship history between donor and recipient, even though an affective bond between them in its manifest speech can be evident. ("…donor for the father, who has hepatic cirrhoses…referrers being very overwhelming with the fact of him being the compatible one, this in function of the behavior of the father, that does not respect the medical recommendations, the donor questions the attitudes of the father, and on the other hand he feels in the obligation to help his father considering a time that his father also helped the donor, and was the only one who trusted the donor when he used drugs, and also tried to commit suicide... the donor says to believes that he must donate its liver for the father, therefore "this will be the only chance to rescue pass lives questions he has with his father"....donor says that his mother and grandmother doesn't approve the donation because they believe the recipient does not want to be helped and also questions if it is worth it to risk donor's life considering someone who even knowing its restrictions does not accept the fact of being sick." PD 83).

The internal conflicts category could be related to category "openlymotivated" which was used in leterature (Walter, Papachristou, Danzer, Klapp & Frommer, 2004). This study found that certain expectations and desires expressed only indirectly in interview relates to way that recipient-donor relationship can be modified or qualitatively improved after donation. The expectations can even be extended to desire to modify the character of receiver which would facilitate a more harmonious relationship post-transplant. These behaviors suggest ways to deal with the situation generated by the transplant (Walter, Papachristou, danzer, Klapp & Frommer, 2004).

Among the category of not close relatives or not relatives, 72% (n=31) of subjects had bond kinship as their manifest motivation for LDLT; and 28% (n=12) mentioned altruistics motivations as the main reason leading the donation. Among the motivations interpreted from the speech of the donor, 65% (n=28) related the affective predominance and 35% (n=15) the motivation was a sort of identification with the recipient. ("…donor and recipient met thru donor's wife, who works and is close friend to recipient. Donor says that he took an interest to donate because he believes to be a sufficient healthy person able to help someone, and also because he knows there are only a few risks in the procedure and can not identify any reason to not donate." PD 105). These findings corroborates with theories that altruism is not restricted to familiar relations (Cole M & Cole S. O Desenvolvimento da criança e do adolescente. Trad. Magda F. Lopes. Porto Alegre: ARTMED; 2003).

Moreover, an extensive study conducted in the United States of America evaluated 731 PDs who were considered to be altruistic donor's, which are the donor's who doesn't have any direct bond to the recipient and had become a PD to whom would be in the transplant list to LDLT. Of all the evaluated donors only 19 were approved for donation. Using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) these approved donors were found to be self-directed, self-confident and interested in others. There were also no traditional transcendent/religious values or thrill seeking, which drove their behavior. The study also highlighted the importance of offering informative material and chances for clarification among the procedure giving the choice to all who exercised their option to donate. On the other hand, the study pointed out the importance to extend the knowledge about this population so that the number of donations is benefited by the compatibility of these types of donors (Jendrisak, 2006).

In the studied sample of PDs the majorities of the survey varirables were the masculine sex, married, and of the religion catholic, (56.3%, on the other hand did not have any registration of its religion position) the education level was mostly around secondary school, and they had an active employment status. The majority of participants also had a close bond to the recipient (parents and children). These results relate to the findings of the

North American study, which found the PDs population to be married, professionally active and had completed at least the secondary school, and also the greater part of the PDs were genetically related to the recipient. The option to donate was more hegemonic among parents, siblings and adult children, considering the genetic relation; and among spouses considering the no genetic bond (Rodrigues Windows, Guenther, Newman, Kaplan & Howard, 2006).

The presence of PDs of the masculine and feminine genre did not present significant statistically differences (58% masculine donors and 47.2% feminine donors, respectively). However, literature mentioned above points that there are a majority of PDs of the feminine sex. Is suggested that factors such as genre differences, subtle familiar coercion, social expectations and differences in the contribution to the family income, may explain the possible reasons for women to donate more than men (Rodrigues, Windows, Guenther, Newman, Kaplan & Howard, 2006).

During the interview analysis it was possible to identify that the PDs had considered aspects like the possibility of getting an absence license of work and resource possibilities offered to the recipient during the post-surgery before candidate to the LDLT. This means that in situations where the donation was from a parent to their children, and where the father could not be absent from work to undergo the donation, the mother would become the candidate to LDLT instead. Or on the other hand in case the recipient needed a care-giver during post-surgery, the father would candidate himself to donation so that the mother would be able to look after the children. These observations indicate that the decision making process to the transplant involves all the family members, which was also founded in other study (Forberg, Nilsson, Krantz & Olausson, 2004).

In some cases we observed that both, mother and father would be candidates for the LDLT so that the process would be more agile in case one of them is not compatible during other clinic examinations. This fact points out that the parental donation is not a freely decisive event, considering that there is not another option apart from donate due to the situation coercitive conditions imposed to the parents by their social role as well as the close relationship between parents and children. The obligation involved in accomplish the transplant perceived for the parents makes possible to emerge adverse experiences as to risk the son to the death, to win the proper fear of the death, to live with the guilt of not having helped their child and to experience the transition of being a healthy donor for a sick person (Forberg, Nilsson, Krantz & Olausson, 2004). It is suggested that the care given to the parents in this situation emphasizes these relations in pre-transplant and posttransplant, thus aiming to support the PD and to increase the cooperation among the members of the family during the transplant.

Knowledge of the transplants risks and procedures has limited influence on the motivation to the transplant, given that the transplant is seen as the unique chance to save the life of the recipient (Forberg, Nilsson, Krantz & Olausson, 2004). In our sample 88.1% of the PDs showed good knowledge of the transplants risks and procedures, from then on it can be said that the motivation to donate involves cognitive, emotional and interpersonal aspects. Concerns of the scars and unreliability of the procedure were rarely mentioned in the interviews. When it did occur, it was suggested by the psychologist that the PD return for a reevaluation after some clarifications with the medical team responsible for the transplant and after contact with persons who have gone thru a similar situation of transplant. This action was important so that during the reevaluation the PD could show more confidence and security facing the pros and cons of the procedure and with the team that would take him and his relative through the donation. Or alternatives as these aims to emphasize to the PD the hope of that everything will turn out well in the transplant (Forberg, Nilsson, Krantz & Olausson, 2004).

Clarification concerning the transplant also would be benefited by analyzing the expectations of the PD facing the transplant. In this way we have access to see how the donor can perceive the situation after the donation. Different studies had investigated the PD's situation, from diverse aspects of this. In the evaluation of expectations concerning the transplant by the questionnaire Living Donation Expectancies Questionnaire a study found that the PD mainly had their expectations in a personal growth and interpersonal benefit. PDs related to the recipient had their expectations connected to an interpersonal benefit, while those PDs not related to recipients had in prospect the health and other consequences linked to the transplant. Relating expectations and the gender of the donors it was found that the men had greater expectation of profit or something in exchange and to the consequences to their health (Rodrigues, Windows, Guenther, Newman, Kaplan & Howard, 2006).

Our study, however did not evaluate the expectation of the potential givers.

Despite these issues, we understand that considering the material in question, an adequate treatment was held and the limitations of the results were well comprehended. In future studies we will have some parameters to be investigated with wider clarity from what it was found in this study.

References

Bardin, L. (1997) Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Cole, M. & Cole, S. (2003) O Desenvolvimento da criança e do adolescente. Trad. Magda F. Lopes. Porto Alegre: ARTMED. [ Links ]

Forsberg, A., Nilsson, M., Krantz, M. & Olausson, M. (2004) The essence of living parental liver donation - donor's lived experiences of donation to their children. Pediatr Transplantation, 8; 372-380. [ Links ]

Gerken, G.. (2003) Evaluation and Selection of the Potential Living Donor: Essen Experience. Transplantation Proceedings, 35: 917. [ Links ]

Jendrisak, M.D., Hong, B., Shenoy, S., Lowell, J., Desai, N., Chapman, W., Vijayan, A., Wetzel, R.D., Smith, M., Wagner, J., Brennan, S., Brockmeier, D. & Kappel, D. (2006) Altruistic Living Donors: Evaluation for Nondirected Kidney or Liver Donation. American Journal of Transplantation, 6: 115-120. [ Links ]

Jowsey, S.G. & Schneekloth, T.D. (2008) Psychosocial factors in living organ donation: clinical and ethical challenges. Transplantation Reviews, 22: 192-195. [ Links ]

Karliova, M., Malagó, M., Valentin-Gamazo, C., Reimer, J., Treichel, U., Franke, G.H., Nadalin, S., Frilling, A., Gerken, G. & Broelsch, C.E. (2002) Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: a 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation, 73(11):1799-804. [ Links ]

Miller, C. (2008) Ethical dimensions of living donation: experience with living liver donation. Transplantation Reviews, 22: 206-209. [ Links ]

Papachristou, C.,Walter, M., Dietrich, K., Klupp, J., Klapp, B.F. & Frommer, J. (2004) Motivation for Living-Donor Liver Transplantation from the Donor's Perspective: An In-Depth Qualitative Research Study. Transplantation; 78(10): 1506-1514. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, J.R., Widows, M.R., Guenther, R., Newman, R.C., Kaplan, B. & Howard, R.T. (2006) The expectancies of living kidney donors: do they differ as a function of relational status and gender? Nephrol Dial Transplant, 21: 1682-1688. [ Links ]

Surman, O.S. & Hertl, M. (2003) Liver donation: donor safety comes first. Lancet, 362: 674-675. [ Links ]

Walter, M., Bronner, E., Steinmuller, T., Klapp, B.F. & Danzer, G. (2002) Psychosocial data of potencial living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transp, 16: 55-9. [ Links ]

Walter, M., Papachristou, C., Danzer, G., Klapp, B.F. & Frommer, J. (2004) Willingness to donate: an interview study before liver transplantation. J Med Ethics, 30: 544-550. [ Links ]

Recebido: 20/09/2015 / Corrigido: 29/09/2015 / Aceito: 06/10/2015.

1 Psychology; Master in Oncology at Fundação Antonio Prudente - Centro de Tratamento e Pesquisa Hospital do Câncer AC Camargo; Universidade de São Carlos - Faculdade de Psicologia anacarolinastaniscia@yahoo.com.br - tel 97544-0979.

2 Psychiatry; Master and Doctorate degree in Oncology at Fundação Antonio Prudente - Centro de Tratamento e Pesquisa Hospital do Câncer AC Camargo; Universidade Nove de Julho- Rua dos Pinheiros, 498, cj. 152 Pinheiros - tel. 2309-4590-celialdacosta@terra.com.br .

3 Psychology; Psycho-oncology Specialist -Degree at Fundação Antonio Prudente ; Master in Oncology at Fundação Antonio Prudente - Centro de Tratamento e Pesquisa Hospital do Câncer AC Camargo;Rua Gandavo, 236 Vila Mariana -Sao Paulo/SP. Tel. 99836-1907 rodriguezmcs@hotmail.com .

4 Psiquiatra da Infância e adolescência. Professor Livre-Docente pela Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo. Professor Associado do Instituto de Psicologia da USP. Rua dos Otonis, 697, São Paulo/SP.Tel. 5579-2762 .