Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.17 no.3 São Paulo dez. 2015

AVALIAÇÃO PSICOLÓGICA

Revision of the Aggressiveness dimension of Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory

Revisão da dimensão agressividade do inventário dimensional clínico da personalidade

Revisión de la dimensión agresividad el inventario dimensional clínico de la personalidad

Lucas de Francisco CarvalhoI; Giselle PianowskiI; Fabiano Koich MiguelII

I Universidade São Francisco, Itatiba – SP – Brasil

II Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina – PR – Brasil

Abstract

The present study aimed to review the Aggressiveness dimension of the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory (IDCP) in two steps: the first focused on developing new and the second for testing the psychometric properties in a sample of 230 subjects, 176 women, aged between 18 and 63 years, with minimum education of undergraduate (52.6%). The subjects answered the IDCP, the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5). The first step resulted in 47 items, of which 20 were new. The second step resulted in a composite of 16 items, in two interpretable structure components, antagonism and violence, with internal consistency coefficients of .89 for total, and .82 for each component. The analysis of the scale with NEO-PI-R and PID-5 revealed consistent and expected correlations. The data reveal the adequacy of the new Aggressiveness dimension of IDCP.

Keywords: psychological assessment; personality traits; psychometrics; personality disorders; DSM-5.

Resumo

O presente estudo teve como objetivo a revisão da dimensão Agressividade do Inventário Dimensional Clínico da Personalidade (IDCP) em duas etapas: uma voltada para elaboração de novos itens e outra para a verificação das propriedades psicométricas em uma amostra de 230 sujeitos, sendo 176 mulheres, com idade variando entre 18 e 63 anos e escolaridade mínima de universitários (52,6%). Os sujeitos responderam ao IDCP, ao Inventário de Personalidade NEO Revisado (NEO-PI-R) e ao Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5). A primeira etapa resultou em uma versão de 47 itens, dos quais 20 eram novos. A segunda resultou em uma dimensão composta por 16 itens, em dois componentes interpretáveis, antagonismo e violência, com coeficientes de consistência interna de 0,89 para o total e 0,82 para os componentes. A análise da dimensão com o NEO-PI-R e o PID-5 revelou correlações coerentes e esperadas. Os dados demonstram a adequação da nova dimensão agressividade do IDCP.

Palavras-chave: avaliação psicológica; traços de personalidade; psicometria; transtornos da personalidade; DSM-5.

Resumen

El presente estudio tuvo como objetivo revisar la dimensión Agresividad del Inventario Dimensional Clínico de la Personalidad (IDCP) en dos pasos: uno se centró en el desarrollo de nuevos elementos y otro para probar las propiedades psicométricas en una muestra de 230 sujetos, 176 mujeres, con edades entre 18 y 63 años y escolaridad mínima de universitarios (52,6%). Los sujetos respondieron el IDCP, el Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado (NEO-PI-R) y el Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5). El primer paso se tradujo en ítems, de los cuales 20 eran nuevos. El segundo dio lugar a una mezcla compuesta de 16 ítems, dos componentes interpretables, el antagonismo y la violencia, con coeficientes de consistencia interna de 0,89 para el total y 0,82 para los componentes. El análisis de la dimensión con NEO-PI-R y el PID-5 reveló consistente y esperado correlaciones. Los datos demuestran la idoneidad de la nueva dimensión agresividad del IDCP.

Palabras clave: evaluación psicológica; rasgos de personalidad; psicometría; trastornos de la personalidad; DSM-5.

The construction of measures for assessment of pathological manifestations of personality has been the focus of numerous international studies (Handler & Meyer, 1997; Strack & Millon, 2007; Widiger & Trull, 2007). This concern and investment has resulted in a wide range of options for clinical use, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 (MMPI-2), the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory III (MCMI-III), the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis II Disorders (SCID-II). Amongst them, self-report scales have gained emphasis for their practicality (Millon, Millon, Meagher, Grossman, & Ramanath, 2004; Millon, 2011).

In the Brazilian context, a search in the Psychological Tests Assessment System (SATEPSI) finds some evaluation measures of personality, for example, the Factorial Personality Inventory (IFP), the NEO PI-R Personality Inventory, and Factorial Personality Battery (BFP), which are self-report scales for personality assessment. However, corroborating the data presented by Carvalho, Bartholomeu and Silva (2010), those are not tools specifically aimed at pathological levels, which reflects the nationwide shortage of measures to evaluate dysfunctions in personality. This research aims at improving the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory – IDCP (Carvalho & Primi, 2015), specifically the Aggressiveness scale, seeking to provide Psychology professionals in Brazil with appropriate measures for personality assessment of pathological levels.

With personality understood as an individual’s stable pattern of functioning, personality disorders can be understood as an individual’s stable set of dysfunctional features, conveying maladaptive manifestations and harmful consequences in their lives (Clark 1990; Millon et al., 2004). In categorical perspective, according to the latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-5 (American Psychiatry Association [APA], 2013), personality disorders can be identified in the population by the steady presence of pathologic manifestations in personality dimensions with their traits involving interpersonal and identity deficit, inconsistent with developmental stages, socio-cultural contexts, medical conditions or substance use..

Understanding personality traits in a continuum that ranges from healthy expressions to pathological levels, disorders relate to the manifestation of one or more characteristics in levels that are considered pathological, which causes, in adaptive terms, dysfunctions in the individual (Millon et al., 2004; Widiger & Trull, 2007). In that sense, the identification of personality functioning – healthy or pathological – depends on the assessment of the characteristics or traits that comprise it, in their varied levels.

Personality assessment focuses on understanding the specific characteristics and their combinations and larger groupings, which is understood today as the dimensions of personality. Personality, from this perspective, is accessed by identifying the levels where individuals are located in the dimensions of personality by drawing up a profile, whether it is adapted and appropriate, or dysfunctional and detrimental to the individual (McCrae & Costa, 1997, 2003).

With a clinical focus toward the gaps in national instrumentalization context that assess pathological levels of personality manifestations, the IDCP was developed (Carvalho & Primi, 2015). The IDCP was developed based on diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR – DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2003) and Millon’s theory (Millon et al., 2004; Millon, Grossman, & Tringone, 2010).

In its original version, the scale is made up of 163 items in twelve factors, which make it possible to identify pathological functioning of the personality and the establishment of the individual’s profiles (Carvalho & Primi, 2015). The component dimensions, namely Dependency, Aggressiveness, Mood Instability, Eccentricity, Attention Seeking, Distrust, Grandiosity, Isolation, Criticism Avoidance, Self-sacrifice, Conscientiousness and Impulsiveness showed validity evidences and adequate reliability indices, in general (Abela, Carvalho, Cho, & Yazigi, 2015; Carvalho & Primi, 2015, in press; Carvalho, Primi, & Stone, 2014).

Although satisfactory psychometric properties for dimensions were found, the IDCP is in consolidation phase, being the focus of investments aimed to expanding and deepening the theoretical review of each dimension’s content, in search of improvements in its psychometric properties. It is being searched, for the IDCP dimensions, and increase in representation of the measured constructs that enables obtaining facets from existing dimensions, detailing further assessment based on the instrument (Carvalho, 2014). This is what can be identified in Carvalho, Souza and Primi’s study (2014), focused on the review of Conscientiousness, a dimension that showed the lowest coefficient of reliability (α = .69) in its original version (Carvalho & Primi, 2015); also in Carvalho, Sette, Capitão and Primi’s study (2014), focused on reviewing the Need of Attention dimension; among others (for example, Carvalho & Arruda, in press; Carvalho & Pianowsk i, 2015; Carvalho & Sette, in press).

In line with the above studies, this paper focuses on IDCP’s Aggressiveness scale. According to Carvalho and Primi (2015), such dimension, which showed a reliability index of .91, comprises manifestations consistent with individuals with violent behavior that demonstrate reduced consideration for the others in their actions, which may be exemplified by the item “I tend to get violent when my wishes are not met”.

In Primi and Carvalho’s study (2015), the authors observed that most of the items from Aggressiveness scale are related to sadistic, antisocial and negativist per sonality disorders. The sadistic personality disorder, currently not listed among the personality disorders of DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2003) and DSM-5 (APA, 2013), but presented in the third edition of the DSM, is manifested by a consistent pattern of cruelty and violent behavior characterized by a clear intention to establish dominance or intimidation in the pursuit of private interests, constant manifestations of humiliation of a subordinate causing social embarrassment, pain imposition and pleasure in other people’s physical or psychological suffering and clear interest in issues such as violence, torture, terror and others (APA, 1987; Millon et al., 2004).

In a different way, although with some related features, antisocial personality disorder shows a behavioral pattern aimed at the violation of the rights of others characterized by not conforming to norms, frequent history of infractions, propensity to cheat in search of advantages and personal benefits. Such individuals present themselves as irritable and with explicit aggressive behavior, being also unconcerned about the safety and integrity of the others, with clear manifestations of indifference and lack of remorse for any harm inflicted on others (APA, 2003, 2013; Millon et al., 2004).

And lastly, the negativist personality disorder, also called passive-aggressive, not included in the last two versions of the DSM (APA, 2003, 2013), consists of a functioning in which the individual reveals a negativist and passive behavior towards social and personal demands. This pattern is expressed by constant refusal to commit to their responsibilities and duties, manifesting a negative experience in interpersonal relations, with frequent complaints of incomprehension and contempt of others, and unfounded criticism and resentment of others’ success. The negativists pr esent themselves oscillating between a more constricted or passive posture and a hostile and aggressive manner (APA, 2003; Millon et al., 2004).

It is possible to observe that, on the one hand, IDCP’s Aggressiveness dimension contemplates a wide range of characteristics related to the presented disorders; on the other hand, these characteristics have a common underlying construct that aggregates them, which is Aggressiveness. As pointed out by Carvalho and Primi (2015, in press), the IDCP dimensions presented adjustments regarding psychometric properties (validity evidence and internal consistency reliability coefficient). However, according to the authors, there is need for continuous improvement and refinement of the instrument dimensions, taking into account the current literature, besides the accumulation of favorable validity evidence for the test. In this sense, the present research is based on the procedures from previous studies that have sought to review other IDCP dimensions (Carvalho, Sette et al., 2014; Carvalho, Souza et al., 2014; Carvalho & Arrud a, in press; Carvalho & Pianowski, 2015; Carvalho & Sette, in press), in order to review the Aggressiveness scale of the IDCP. In addition to review and verification of the psychometric properties, this research also sought to verify the possibility of dividing the scale in factors, so that these may be further used in the investigation of specific profiles according to the assessed latent construct.

Method

The review of the Aggressiveness scale from the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory (IDCP) was implemented in two steps, namely Step 1 focused on the development of new items through analysis of literature, and Step 2 intended for checking psychometric properties of the reviewed version.

Step I

Procedures

The development of new items for the Aggressiveness scale of the IDCP was done through consultation of relevant literature for understanding the pathological manifestations of personality, which were: section 3 of the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), facets of Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – PID-5 (Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson, & Skodol, 2011), the dimensions of the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure – SWAP-200 (Shedler & Westen, 2004) and Clark’s model (1990) that supports the Schedule for Nonadaptive Personality (SNAP).

In sequence, we moved to the analysis of the content from the literature for selecting the characteristics associated with aggressive functioning. Sentences were chosen carefully seeking representation of events associated with the dimension to be revised. After the implementation of selected content in a spreadsheet in the original language, English, we moved to their translation by two independent judges, authors of this study, and finally obtaining the final and consensual translation that has been established as a basis for creating new items.

We listed the most considered attributes and followed to the preparation of items for each feature, a group composed of five members, being the authors of this work and three doctoral students in Psychology who participated in a study group to review the dimension. The preparation of the items was performed independently. With the new set of items created, the authors, individually, selected the items considered most appropriate. With the final pre-selection made, each item was analyzed, searching for consensus in selecting the best items, which then made up the final set to be tested. For the final assembly, the authors based on criteria such as the appropriateness of writing (clarity and no ambiguity), typical features to the latent construct (Aggressiveness) still not well represented in the IDCP, the scope of pathological levels of manifestation, and final agreement on the content relevance to Aggressiveness dimension.

Step II

Participants

This research samples consists of 230 subjects, of whom 176 are women (76.4%), aged between 18 and 63 years (M = 23.0, SD = 9.44), and mainly undergraduates (52.6%), graduates (17.8%) and post-graduate students (10%). The subjects were assessed by convenience by the researchers. As for the history of psychiatric/psychological treatment, 22 subjects (9.5%) reported that they have attended or are attending, and 2.2% (N = 5) made use of psychotropic medication..

Instruments

The instruments used in this research were IDCP (Carvalho & Primi, 2015), the Brazilian version of the NEO Personality Inventory Revised – NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 2009) and the Brazilian version of the PID-5 (Krueger et al., 2011). The instruments are described below.

The IDCP is an instrument developed to evaluate pathological personality characteristics based Millon’s theory (Millon et al., 2004, 2010) and axis II diagnostic criteria from the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2003). Originally, the instrument consists of 163 items in a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 means it as nothing to do with me and 4 means it is totally related to me, with an average administration time of 25 minutes. The IDCP items cover 12 dimensions of personality, namely, Dependency, Aggressiveness, Mood Instability, Eccentricity, Attention Seeking, Distrust, Grandiosity, Isolation, Criticism Avoidance, Self-sacrifice, Conscientiousness and Impulsiveness. The scores generated by the IDCP enable the identification of pathological features of personality as well as the establishment of individual’s functioning profiles (Carvalho & Primi, 2015). As for its psychometric properties, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyzes were performed, analysis of the items using rating scale model, and verification of reliability coefficients, which were satisfactory, considering a cutoff of .70 (Nunnally, 1978) to all dimensions of the instrument except Conscientiousness, with a value of .69 (Carvalho & Primi, 2015, in press; Carvalho, Primi et al., 2014). Validity evidences were found to IDCP based on the relationship with other variables (Abela et al., 2015; Carvalho & Primi, in press), particularly with the dimensions and facets of the NEO-PI-R and psychiatric diagnoses. In general, the expected relations between the dimensions of the facets and dimensions IDCP and NEO-PI-R have been found, as well as with different axis II psychiatric diagnoses of the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2003).

The NEO-PI-R is considered a self-report inventory focused on the assessment of adult personality, composed of 240 items in a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree, with administration time of approximately 25 minutes. The instrument covers five personality dimensions, namely Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. However, for this study, we assessed only the Neuroticism and Agreeableness dimensions, considered related to the manifestation of the Aggressiveness dimension. The manual of the Brazilian version of the instrument presents studies showing satisfactory validity evidence and reliability (Costa & McCrae, 2009).

The PID-5 consists of a self-report inventory developed for assessing the pathological features of personality contained in the B criteria of the DSM-5 personality disorders categories. It consists of 220 items, which must be answered on a 4-point Likert scale, with 0 (zero) equal to very false or often false and 3 equal to very truthful or often truthful. The PID-5 comprises 25 facets, grouped into five dimensions, namely, Negative Affection, Detachment, Antagonism, Disinhibition, and Psychoticism. For this study, however, we used only Callousness, Hostility and Impulsivity facets. There were no national studies verifying the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the instrument, but Krueger et al. (2011) present data indicating the adequacy of the original version of the test.

Procedures

After submission and approval of the Ethics in Research Committee (Caae n. 2199 2113.1.0000.5514), the data collection was started. The administration was done collectively, with an approximate duration of 40 minutes in one session per class, in university classrooms. According to demand and access, some applications occurred individually in private establishments. After explaining the research goals and with the participants’ consent by signing the Informed and Free Consent Term, the instruments were administered, with alternated sequences of presentations.

After that, data were typed into a spreadsheet and proceeded to the statistical analysis. Initially we proceeded to the parallel analysis for polychoric variables using the R software version 2.15.3 to stipulate the maximum number of factors to be tested. Then the exploratory factor analysis was performed with adjustment ratio (E-SEM), using MPlus software version 6.12. In the case of E-SEM, we used geomin oblique rotation and Robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) extraction method, considered robust and suitable for polychoric variables. Furthermore, the fit indices were analyzed, X2/df, RMSEA, CFI e SRMR.

Based on the data found, which did not allow the establishment of factors and did not demonstrated interpretability, as a second procedural option for the best dimensional structure, we proceeded to the principal component analysis (PCA), using the statistical program SPSS version 17. The use of PCA aimed to replicate the analytical strategy used in two dimensions already revised the IDCP (see Carvalho, Sette et al., 2014; Carvalho, Souza et al., 2014) and maximize the possibility of finding sets of items no more than moderately correlated. The criteria used for the PCA were 1. restrict the number of items in groups to the total number set by the parallel analysis, i.e., two components, 2. filter items with loads lower than .30, and 3. use an oblique rotation (oblimin), considering moderate correlations between the components. Finally, correlation analyses were performed between the components found for the Aggressiveness dimension, the two NEO-PI-R dimensions and the three PID-5 facets.

Results

The literature review resulted in the identification of the constructs and sentences considered relevant for Aggressiveness dimension of the IDCP. The listed constructs were Indifference and Hostility, from the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), Callousness, Hostility, Deceitfulness and Manipulativeness based on PID-5 (Krueger et al., 2011), Hostility from SWAP and Anger/Aggression, Exploitation, and Insincerity from the SNAP base model (Clark, 1990).

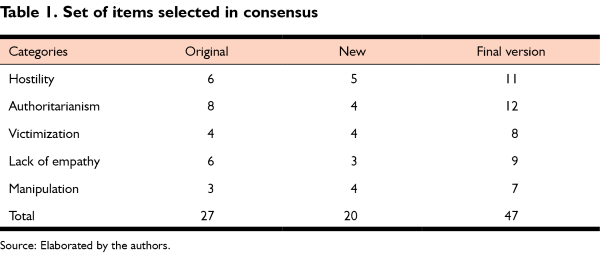

The selected constructs were divided into 66 groups of characteristics related to Aggressiveness. Such characteristics were the basis for the development of new items, which was made independently by five researchers, resulting in the construction of five to six items per feature, totaling an initial production of 354 items, independently developed by the authors of this study. The pre-selection of the most suitable items occurred independently and then, by consensus, resulting in 60 items. For the final selection of the items we considered as a criterion the content identification not well represented in the original items of the IDCP Aggressiveness dimension, which was also performed independently, followed by consensus. The final version of the new Aggressiveness dimension for administration was composed of 47 items, including original and new, arranged in categories as shown in Table 1.

All elaborated categories based on the selected constructs as relevant to the Aggressiveness dimension were already included in the IDCP (see Original column, which refers to the number of original items). The included items sought to add information about the manifestation of the category which were not yet represented by the original items. The Hostility category, consisting of 11 items, corresponds to items dedicated to general behaviors that express aggression, violence, irritability manifestations, and hostility in various situations. The Authoritarianism category, consisting of 12 items, corresponds to items dedicated to aggressive behavior specifically directed to an authoritarian attitude with initiative of intimidation and domination in their interpersonal relationships, which can manifest physically. The Victimization, composed of eight items, includes content related to detachment of the blame for aggressive attitudes, with expression of victimization reaction and resentment towards others. Lack of Empathy, composed of nine items, is directed to a lack of concern aand consideration to each other regarding their attitudes and a pleasure inclination regarding other people’s suffering. Finally, the category Manipulation, composed of seven items, corresponds to search efforts for benefit and advantages. The set of 47 items was administered and, subsequently, investigated in the psychometric perspective. Importantly, the distribution of items into categories aimed to ensure that items for the different characteristics and behavioral manifestations related to aggression were developed and/or were already covered in then dimension. In this sense, we point out that there was no theoretical expectations regarding the number of factors which dimension Aggressiveness could be partitioned.

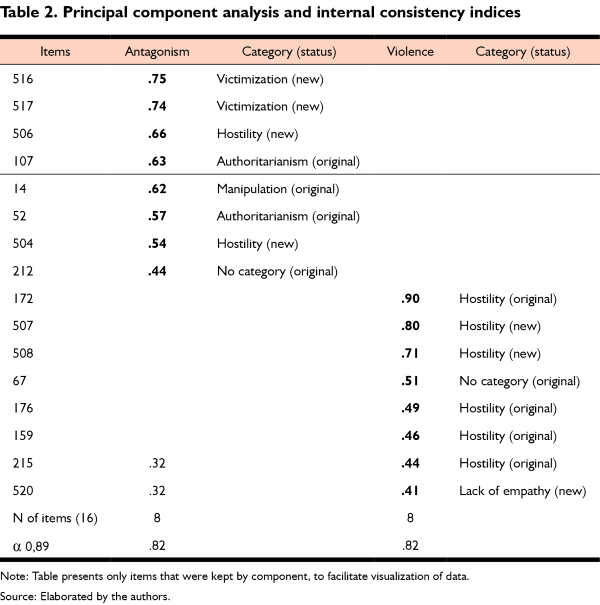

We initially used the parallel analysis for polychoric variables, which suggested a solution to two factors with significant eigenvalue not shown to chance. By E-SEM, we forced one and two factors solutions. We analyzed the adjustment ratios generated for the two models and interpretability of factors. The two factors solution, despite minimally satisfactory fit indexes (X2/df = 2.35; RMSEA = .08, CFI = .60; SRMR = .07) considering the criteria from Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen (2008), presented problems regarding the interpretability of the factors, i.e., it was not possible to identify a clear pattern that would enable identifying remarkable and distinguishable characteristics between the two groups of items. Understanding that the choice of this model would remove the identification of profiles based on IDCP Aggressiveness factors, we decided to further explore data in order to obtain more than one factor for all items. We then executed a principal component analysis (PCA), again using parallel analysis as a basis for retaining the number of components, and in this case, the procedure indicated retention of up to two components. The results enabled the maintenance of a structure of two interpretable components for the Aggressiveness dimension, of which the charges found, the number of items held by component and the internal consistency index (Cronbach’s alpha) and the category to which each item is part, can be seen in Table 2.

The final version of the revised Aggressiveness dimension was composed of 16 items, 9 original and 7 new items into two components, namely Antagonism (8 items, 4 new) and Violence (8 items, 3 new). Antagonism covered features like conduct and interest facing aggression in general, with repression and imposition initiatives. Violence includes attributes related to behaviors of physical aggression, such as intense experience of anger and lack of control, with physical and moral aggression initiatives. In addition, it is also possible to notice that the Antagonism component includes items from different categories, mainly Victimization, Hostility and Authoritarianism, with two items of each of these categories. But the Violence component consists primarily Hostility category items.

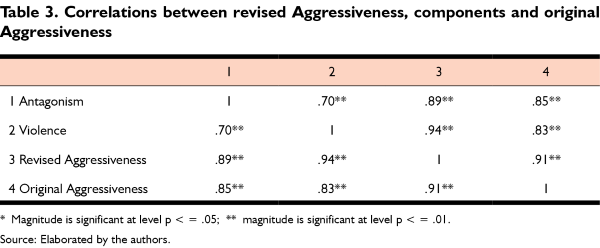

For the viability of this IDCP dimension, in a test consisting of 12 dimensions, we sought to expressively reduce the number of items. Three main criteria were adopted for the exclusion of items, namely, 1. reduced impact of the item on the internal consistency of the component, 2. significant charges in more than one component (smaller accepted loads in intracomponent difference was .50) and 3. interpretive inconsistency of the item in the component. As an additional procedure for dimensional reduction, some items that had adequate charge were excluded, based on the redundancy analysis of its contents, discarding items that did not compromise the dimension’s psychometric quality. The Antagonism and Violence components showed both internal consistency of .82, and the total set obtained an index of .89. From the establishment of the dimension’s internal structure, Table 3 shows the correlations between reviewed dimension and components, as well as the total score of the original Aggressiveness dimension from IDCP.

The data shows a moderate to high correlation between the Antagonism and Violence components. In addition, we also observed a high correlation between the magnitude of total scores, demonstrating a high shared variance between the original set and the new set of items. Next, Table 4 displays the correlation results of the Aggressiveness dimension and components with the NEO-PI-R Agreeableness and Neuroticism dimensions and facets and the PID-5 facets.

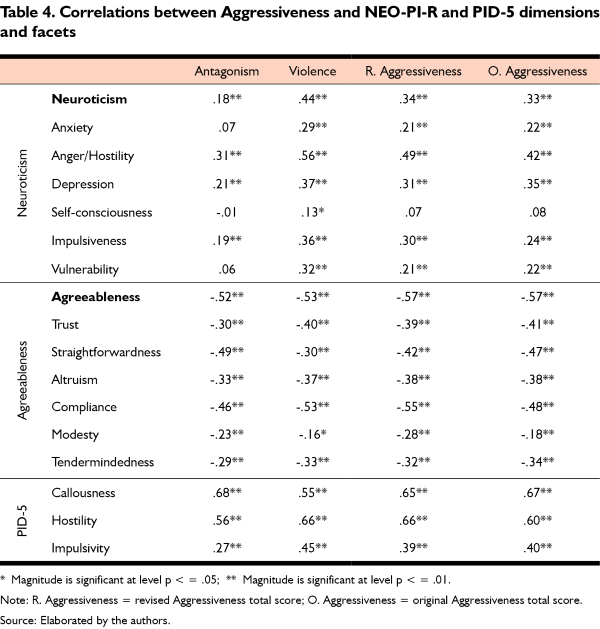

In Table 4 it is noted that all significant magnitudes of IDCP with Neuroticism were positive, and the total scores of Aggressiveness showed similar magnitude with Neuroticism, but more significant scores with Anger/Hostility facet. Regarding Neuroticism facets, Aggressiveness components also showed higher magnitudes with NEO-PI-R Anger/Hostility. Regarding Agreeableness, different from what was observed with Neuroticism, all correlations were negative with IDCP. The total scores, revised and original, had moderate magnitude with Agreeableness, and facets showed larger magnitudes with Compliance and Straightforwardness. Concerning the Aggressiveness components with NEO-PI-R facets, Antagonism showed greater magnitude with Straightforwardness and Compliance, and Violence with Compliance and Trust.

The results with the PID-5 showed clearly higher correlations between IDCP and the PID-5, compared with the IDCP and NEO-PI-R. With regard to the total scores of Aggressiveness, the compound made only by original items showed higher magnitude with Callousness and less with Impulsivity, and the set of revised items showed higher magnitudes with Callousness and Hostility and lower with Impulsivity. Antagonism was related more with Callousness, and Violence more with Hostility.

Discussion

IDCP Aggressiveness scale is designed to assess consistent features of violent behavior with low consideration for the other (Carvalho & Primi, 2015, in press). To expand the representativeness of the construct assessed by the dimension, we listed attributes not yet comprised by Aggressiveness dimension in its original version. Based on the literature on aggression and personality disorders related to the IDCP dimension (Abela et al., 2015), constructs were selected, regarding manifestations of Callousness, Hostility, Manipulativeness, Deceitfulness, Anger, Exploitation, and Insincerity, considered to be coherent for the expansion of the dimension in the construction of new items. All selected constructs showed contents more or less directed to what is measured by IDCP Aggressiveness dimension (Carvalho & Primi, 2015), i.e., aggres - sive behavior in different situations and little consideration for the other. As a result of the first step, we obtained a new version to the IDCP Aggressiveness dimension with the inclusion of 20 new items to the original 27, totaling a sample of behaviors related to aggression grouped as hostility, authoritarianism, victimization, lack of empathy and manipulation.

At first, we used the procedures described above in studies that reviewed other IDCP dimensions (e.g., Carvalho, Sette et al., 2014; Carvalho, Souza et al., 2014). However , these procedures did not allow the establishment of factors composing the Aggressiveness dimension. Not composing the dimension with different sets of items would make it impossible to obtain distinguishable profiles in addition to calculating a total score. So other analytical procedures were adopted. These procedures produced interpretable and consistent components and, thus, data were used for the composition of the internal structure of Aggressiveness dimension. These data should allow investments in research to generate profiles within the dimension.

Psychometric analysis conveyed a new dimension consisting of 16 items divided into two components, Antagonism and Violence, with adequate internal consistency coefficients (Embretson, 1996; Nunnally, 1978). The Antagonism component refers more properly to overall aggression, including demonstrations of victimization, pleasure with violence, hostility and others, which can be best seen in the case of item “Those who have harmed me have to pay for it”. The Violence component, in turn, includes events directed to the physical aggression, as exemplified in “I tend to become violent when my desires are not met”. On one hand, the five categories (see Table 1) are represented by items in both components of Aggressiveness; on the other, seven out of the total number of items are part of Hostility category, which is the most represented in the revised scale. Indeed, one must consider that typical functioning related to the Aggressiveness dimension (i.e., sadistic, antisocial and oppositional) has features in common mainly regarding aggressive behaviors in diverse contexts and in various expressions, which is represented by category Hostility, and part of the core construct assessed by Aggressiveness dimension (Carvalho & Primi, 2015).

It is noteworthy, though, the new dimension’s greater concision (16 items) compared to the original version (27 items), keeping the internal consistency coefficient very similar to the original. That is, even with a smaller number of items, the internal consistency of the revised scale shows an acceptable level of measurement error. The most succinct number of items for the IDCP dimension aims at favoring the use of the IDCP in its set of 12 dimensions in the clinical context. Thus, it is understood that the results for the factor solution suggested validity evidence based on the internal structure, since the components that were found are interpretable and consistent with the basic literature.

Regarding the correlations, it is possible to observe that the set of original items (Carvalho & Primi, 2015) is highly correlated with the Aggressiveness reviewed dimension, indicating they have similar functioning. In addition, the correlation of the total scores with the Agreeableness and Neuroticism dimensions and their facets indicate similarity between them. The observed pattern with Neuroticism and Agreeableness, namely, positive correlations with Anger/Hostility and general negative magnitudes, are consistent with what is assessed by these dimensions, since this facet of Neuroticism assesses the tendency to experience anger and related states, and low scores on Agreeableness are related to interpersonal difficulties (Costa & McCrae, 2009).

The differences between the original and revised Aggressiveness items is most evident in the correlations with PID-5, in a way that the reviewed dimension showed more significant correlations with two of the three PID-5 facets. Still, in both cases, we found smaller magnitudes with Impulsivity facet. This data is coherent, since Impulsiveness is related to inconsequential and little weighted actions and reactions (Krueger et al., 2011), features more related to the last dimension of the IDCP (Impulsiveness); and Indifference and Hostility are associated, respectively, with characteristics related to the lack of empathy, hostility and interpersonal distance, and opponent position and aggressive attitudes towards others, which is more closely related to the latent construct of IDCP Aggressiveness dimension. Still, an important distinction between the original and revised dimension is noted, namely the latter enables the establishment of different profiles for the use of Antagonism and Violence components.

Regarding correlations with the components of Aggressiveness, it is noteworthy that Violence displayed indicators demonstrating a more pathological composition in relation to Antagonism, as it has more significant correlation magnitudes with Neuroticism and also with PID-5, especially in respect to the Impulsivity facet. This fact is relevant, since the Violence component is more related to physical Aggressiveness, and Antagonism component with Aggressiveness in general. With specific regard to Antagonism, the correlation with Anger/Hostility is consistent, taking into account what both of them assess (Costa & McCrae, 2009), and Compliance as well, since low scores in this aspect are related to a tendency of not submitting to others and to dominate them. The relationship with Straightforwardness needs to be further researched. Moreover, Antagonism had more obvious correlations with PID-5 Callousness and Hostility facets, which also makes sense since these two facets present typical characteristics of generalized aggression (Krueger et al., 2011).

Besides this, the correlations with Violence were also conceptually consistent, also displaying greater relations with Anger/Hostility (Neuroticism) and Compliance and Trust (Agreeableness), with the latter facet differentiated regarding Antagonism, but this also requires future studies seeking better understanding of the relationship. In addition, the correlations with the PID-5 showed similar pattern, although the magnitude with Impulsivity has been clearly higher, suggesting that this component is also related to impulsive behaviors and being prone to inconsistency, such as the PID-5 facet (Krueger et al., 2011).

Still regarding the two components that make up the revised scale, one can think of the reaction style as a point of distinction between Antagonism and Violence, i.e., the former more focused in a diffuse aggression, based on interpersonal distance and indifference, and the latter in a reactive and primarily physical – and thus more impulsive and angry – Aggressiveness. Such data are corroborated by the observed correlations. In this sense, talking about the personality disorders mentioned by Carvalho and Primi (2015, in press) as relevant to aggression, it is noteworthy that same reaction contrast, for example, between oppositional personality disorder, consistent with a negativist and passive behavior regarding the social and personal demands (APA, 2003, 2013), and the sadistic, which is manifested by a consistent pattern of cruelty and violent behavior (APA, 2003, 2013; Millon et al. 2004).

Such distinctions are of utmost importance for the confirmation of appropriateness of two structure components for such a cohesive dimension as Aggressiveness, and becomes the basis for directions of studies focused on the profiles in this dimension. Accordingly, in addition to validity evidence based on structure, we emphasize that this study reveals validity evidence based on external relations to the new IDCP Aggressiveness dimension, which can be found in the correlations with the other administered instruments.

The results and discussions presented in this study show we achieved the goal of reviewing the Aggressiveness dimension by elaborating new items and verifying their psychometric properties. As a result, we obtained a dimension comprised of two components with high reliability coefficients, consisting of 16 items, more concise than the original dimension, without impairing its psychometric quality. In sum, its structure enables investment in research for the establishment of profiles related to aggressive functioning.

We identified validity evidence based on the internal structure and in relation with external variables, as well as adequate internal consistency coefficients. The composition of the Antagonism and Violence dimensions of Aggressiveness was adequate and interpretable, with distinctions between the components and cohesion to aggressive operation. The relationship with external variables was favorable to the new dimension, which can be identified in the moderate to high correlations with the constructs listed in the literature as relevant to aggression.

Despite the favorable data, it is necessary that future research continue exploring the limitations and strengths of IDCP Aggressiveness dimension. It is noteworthy studies that seek to investigate the profiles based on the two components established; checking the severity level of the two components found, including their comparison; and research aimed at better understanding the correlations found here specifically between Antagonism and Openness, and Violence with Confidence. As limitations of this study, we cite the number of participants and sample characteristics that do not encompassed clinical patients diagnosed with personality disorders, which was predominantly female.

References

Abela, R. K., Carvalho, L. F., Cho, S. J. M., & Yazigi, L. (2015). Validity evidences for the dimensional clinical personality inventory in outpatient psychiatric sample. Paidéia, 25(61), 221-228. DOI: 10.1590/1982-43272561201510. [ Links ]

American Psychiatry Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd Rev. ed.). Washington: American Psychiatry Association. [ Links ]

American Psychiatry Association (2003). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Rev. ed.). Washington: American Psychiatry Association. [ Links ]

American Psychiatry Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington: American Psychiatry Association [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F. (2014). Avaliação dos transtornos da personalidade no Brasil: o Inventário Dimensional Clínico da Personalidade. In C. R. Campos & T. C. Nakano. Avaliação psicológica direcionada a populações específicas: técnicas, métodos e estratégias. São Paulo: Vetor. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., & Arruda, W. (in press). Revisão da dimensão Isolamento do Inventário Dimensional Clínico da Personalidade. Temas em Psicologia. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., Bartholomeu, D., & Silva M. C. R. (2010). Instrumentos para avaliação dos transtornos da personalidade no Brasil. Avaliação Psicológica, 9(2), 289-298. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., & Pianowski, G. (2015). Revision of the dependency dimension of the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory. Paidéia, 25(60), 57-65. DOI: 10.1590/1982-43272560201508. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., & Primi, R. (2015). Development and Internal Structure Investigation of the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 28(2), 213-221. DOI: 10.1590/1678-7153.201528212. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., & Primi, R. (in press). Prototype matching of personality disorders with the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., Primi, R., & Stone, G. E. (2014). Psychometric Properties of the Inventário Dimensional Clínico da Personalidade (IDCP) using the Rating Scale Model. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 32(3), 433-446. DOI: 10.12804/apl32.03.2014.09. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., & Sette, C. (in press). Criticism Avoidance Dimension of the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory revision. Estudos de Psicologia. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., Sette, C. P., Capitão, C. G., & Primi, R. (2014). Propriedades psicométricas da versão revisada da dimensão necessidade de atenção do inventário dimensional clínico da personalidade. Temas em Psicologia, 22(1), 147-160. DOI: 10.9788/TP2014.1-12. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F., Souza, B. D. B., & Primi, R. (2014). Psychometric properties of the revised conscientiousness dimension of Inventário Dimensional Clínico da Personalidade (IDCP). Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 36, 23-31. DOI: 10.1590/2237-6089-2013-0024. [ Links ]

Clark, L. A. (1990). Toward a consensual set of symptom clusters for assessment of personality disorder. In J. N. Butcher & C. D. Spielberger (Orgs.). Advances in personality assessment. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Costa P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. (2009). NEO-PI-R – Inventário de Personalidade NEO Revisado – Manual. São Paulo: Vetor.

Embretson, S. E. (1996). The new rules of measurement. Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 341-349. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.341. [ Links ]

Handler L., & Meyer, G. J. (1997). The importance of teaching and learning personality assessment. In L. Handler & M. Hilsenroth, M. Teaching and learning personality assessment. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model Fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(8), 53-60. [ Links ]

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2011). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 8, 1-12. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291711002674. [ Links ]

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory perspective. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality Trait Structure as a Human Universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509-516. [ Links ]

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality: Introducing a DSM/ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal. New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Millon, T., Grossman, S., & Tringone, R. (2010). The Millon Personality Spectrometer: a tool for personality spectrum analyses, diagnoses, and treatments. In T. Millon, R. F. Krueger & E. Simonsen (Orgs.). Contemporary directions in psychopathology: scientific foundations of the DSM-V and ICD-11. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Millon, T., Millon, C. M., Meagher, S. Grossman, S., & Ramanath, R. (2004). Personality disorders in modern life. New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Shedler, J., & Westen, D. (2004). Dimensions of personality pathology: an alternative to the five factor model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1743-1754. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.10.1743. [ Links ]

Strack, S., & Millon, T. (2007). Contributions to the dimensional assessment of personality disorders using Millon’s model and the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI-III). Journal of Personality Assessment, 89(1), 56-69. DOI: 10.1080/00223890701357217.

Widiger, T. A., & Trull, T. J. (2007). Place tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist, 62(2), 71-83. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Lucas de Francisco Carvalho

Universidade São Francisco

Rua Alexandre Rodrigues Barbosa, 45

Itatiba – SP – Brasil. CEP: 13251-900

E-mail: lucas@labape.com.br

Submissão: 1º.7.2014

Aceitação: 10.8.2015