Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versión impresa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.22 no.1 São Paulo enero/abr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v22n1p64-88

ARTICLES

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Instruments for measuring perceived and experienced Mental Illness Stigma: a systematic review

Instrumentos de avaliação do estigma percebido e estigma experienciado na doença mental: uma revisão sistemática

Instrumentos de evaluación del estigma percibido y el estigma experimentado en enfermedades mentales: una revisión sistemática

Nicolas O. CardosoI ; Breno Sanvicente-VieiraII

; Breno Sanvicente-VieiraII ; Isabela M. V. FerraciniI

; Isabela M. V. FerraciniI ; Irani Iracema de L. ArgimonI

; Irani Iracema de L. ArgimonI

IPontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

IIPontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

ABSTRACT

In order to investigate which instruments are most utilized when measuring perceived and experienced mental illness stigma (MIS) in adults, and some of the variables that may moderate or interfere in measured outcomes, 101 published empirical and peer-reviewed studies were systematically extracted from electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, EBSCO, Web of Science, and PsycINFO). The results revealed that MIS is commonly evaluated by five scales. When considering the most tested and reported associative effects, age, and symptoms severity were identified as potentially intervening variables. Other variables, such as sex, diagnostic, and treatment regimen (inpatient/outpatient) were evaluated by a few studies and presented inconsistent results. These findings suggest that future studies should use well-established instruments in the literature to assess MIS, as well as to aim for the cross-cultural adaptation of instruments that evaluate MIS since no instruments presented in this review are validated to the Brazilian population.

Keywords: mental health; stigma; mental illness; discrimination; evaluation.

RESUMO

Objetivando investigar quais instrumentos são mais utilizados na mensuração do estigma da doença mental (EDM) percebido e experienciado por adultos, e quais variáveis podem moderar ou interferir nos resultados da mensuração, 101 artigos foram sistematicamente selecionados nas bases de dados eletrônicas (MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, EBSCO, Web of Science e PsycINFO). Os resultados revelaram que existem cinco instrumentos comumente utilizados para medir o EDM. Ao considerar os efeitos associativos mais testados e reportados sobre o estigma, a idade e a severidade dos sintomas foram apontadas como variáveis potencialmente intervenientes. Outras variáveis, como sexo, diagnóstico e regime de tratamento (internamento/ambulatório) foram avaliadas por poucos estudos e apresentaram resultados inconsistentes. Essas descobertas sugerem que trabalhos futuros devem utilizar instrumentos bem estabelecidos na literatura para avaliar o EDM, assim como visar à adaptação transcultural de instrumentos que avaliem o EDM, uma vez que nenhum dos instrumentos apresentados nesta revisão é validado para a população brasileira.

Palavras chave: saúde mental; estigma; doença mental; discriminação; avaliação.

RESUMEN

Con el objetivo de investigar qué instrumentos son más utilizados en la medición del estigma de la enfermedad mental (EEM) percibido y experimentado en adultos, así como las variables que pueden moderar o interferir en los resultados de la evaluación, 101 artículos fueron sistemáticamente extraídos en las bases de datos electrónicas (MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, EBSCO, Web of Science y PsycINFO). Los resultados revelaron que existen cinco instrumentos comúnmente utilizados para medir el EEM. Al considerar los efectos asociativos más comprobados y reportados sobre el estigma, la edad y la severidad de los síntomas fueron identificadas como variables potencialmente intervinientes. Otras variables, como el sexo, diagnóstico y condición de tratamiento (internación/ambulatorio) fueron evaluadas en pocos estudios y presentaron resultados inconsistentes. Estos hallazgos sugieren que trabajos futuros deben utilizar instrumentos consolidados en la literatura para evaluar el EEM, así como para la adaptación transcultural de instrumentos que evalúen el EEM, ya que ninguno de los instrumentos presentados en esta revisión ha sido validado para la población brasileña.

Palabras clave: salud mental, estigma, enfermedad mental, psicología de la salud, discriminación; evaluación.

1. Introduction

Stigma can be defined as a social phenomenon that affects a group of people who presents peculiar characteristics, leading to discrimination and restriction of social participation (Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006; Goffman, 1988). Therefore, stigma arises through cognitive representations and it is currently associated with discrimination and prejudice against one individual or group of individuals (Bos, Pryor, Reeder, & Stutterheim, 2013).

Mental illness stigma (MIS) is one kind of stigma currently present in our society. Just as a mental illness, the stigma itself has several negative outcomes (i.e. psychological, social, and physical) for patients, family members, and caregivers, which may aggravate these disorders (Fox, Earnshaw, Taverna, & Vogt, 2017). The field of MIS is filled with different interpretations related to the definition of stigma types (Corrigan et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2017; Goffman, 1988; Link, 1987).

Recently, Fox et al. (2017) developed the Mental Illness Stigma Framework (MISF) to improve the understanding of the most relevant issues in the area. This framework may be helpful to solve issues in terminology, to offer directions for research, and to improve the study of the field. MIS can be divided, at least, into four different subtypes: anticipated, experienced, perceived or internalized. According to MISF, perceived stigma can be presented in individuals with and without mental illness and it is defined as perceptions of social beliefs, such as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.

Experienced stigma is characterized by the perception of being a victim (recently or throughout life) of stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination. The anticipated stigma relates to the expectation of discrimination (Fox et al., 2017), and they are sometimes associated with internalized stigma (Bos et al., 2013). The internalized stigma can be defined as the internalization of stereotypes, prejudices and social discrimination to the Self (Corrigan et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2017). These types of MIS are related to delayed treatment seeking and adherence by people with mental illness (PWMI) (Bos et al., 2013; Corrigan et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2017).

These problems are a major concern in Brazil, alredy adressed by the federal government in a document entitled "National Agenda for Priorities in Health Research", which was divided into sub-agendas classified by order of priority. According to this document, mental health is the second priority of health research, and stigma is one of the approaches suggested as a research theme and intervention target in the field of mental health (Brasil, 2015).

However, despite all recognized impacts of MIS, there is a lack of research addressing stigma perceptions and experiences of PWMI. Most studies regarding MIS had focused on community and mental health professionals' views about prejudice and discrimination (Mascayano et al., 2016). Therefore, it was suggested that new studies should address perceived and experienced stigma from the patients' perspective (Fox et al., 2017; Mascayano et al., 2016). Furthermore, two recent systematic reviews aimed to evaluate the psychometric quality of instruments developed to assess MIS (Fox et al., 2017; Wei, McGrath, Hayden, & Kutcher, 2017). However, some sociodemographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric variables were not evaluated in those reviews.

Several studies highlighted the importance of considering the effect of some variables during the measurement of MIS (King et al., 2007; Livingston & Boyd, 2010), as they may have a moderator effect on MIS scores, especially on differences between inpatients and outpatients (King et al., 2007; Mascayano et al., 2016), age (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Wong, Collins, Cerully, Yu, & Seelam, 2018), sex (Lacey et al., 2014), symptoms severity (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Sarkin et al., 2014), and diagnostic (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2017). However, to our best knowledge, no systematic review has investigated the effects of those variables on perceived and experienced stigma. Hence, this study aimed to investigate which instruments are most utilized when measuring perceived and experienced MIS in adults. Furthermore, the present research explores some of the sociodemographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric variables that may moderate or interfere in measured outcomes.

2. Method

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). Data were retrieved through searches in five databases: PubMed, Scopus, EBSCO, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Two independent researchers conducted the searches and criteria evaluation between March 4th and 22th 2019. To access the scientific studies matched with the objectives of this review, we used the following search terms: ("mental disorder" OR "mental disease" OR "mental illness" OR "mental health") AND (stigma or prejudice) AND (questionnaire OR scale OR index OR psychometric OR assessment). Descriptors were selected according the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH/PubMed) and The Saurus (PsycINFO).

After completiing the database searches, we imported all the results into Rayyan, a web-based tool (Olofsson et al., 2017). Rayyan was developed to help authors of systematic reviews to save time and produce better quality papers. Its use has increased, particularly because it is a free and easy-to-learn tool. In addition to reducing the time spent on crafting inclusion/exclusion evaluation for database searches, it helps to reduce incidents of possible selection gaps and disparities (Olofsson et al., 2017; Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016).

Two independent researchers assessed titles and abstracts at a first glance. In cases of doubts remaining after the first screening, authors checked full texts. Papers had to fulfill the following criteria for inclusion: (a) to be empirical or quantitative; (b) to be peer-reviewed; (c) to use an instrument with psychometric evidence to measure perceived and experienced stigma, and (d) to have an adult sample (18 to 64 years old) with a mental illness diagnostic. In order to find as many articles as possible, no language or year of publication restrictions were made. As previously stated by Fox et al. (2017), there is a variety of instruments for assessing MIS (400>); therefore, the use of standard measures with psychometric proprieties is recommended. Thus, after the exclusion of duplicates, to better evaluate assessment trends, we also excluded studies that used measures with fewer than five appearances across all reviewed papers.

In addition, as it is common for individuals to be affected by more than one mental disorder (Lai, Cleary, Sitharthan, & Hunt, 2015), we decided to exclude instruments related to perceived and experienced MIS designed specifically to assess the stigma of a single mental illness (e.g., Depression). After these steps were completed, we conducted a manual reference search on all included full-text articles. All remaining papers were fully read for identification of instruments developed in order to measure perceived or experienced MIS.

3. Results

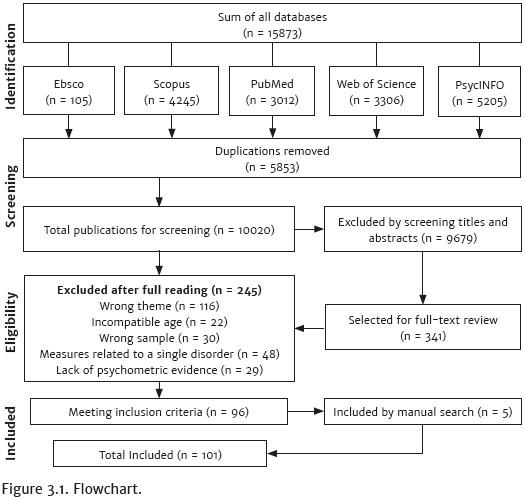

We found 15,873 papers in the initial search. In the end, 101 empirical and peer-reviewed studies met our inclusion criteria. Figure 3.1 shows the flowchart following the PRISMA protocol.

Next, all 101 papers were reviewed again, looking for characteristics of the used measures and the intervenient variables that were taken under consideration in the present study. Publication dates from the included studies indicated that, since 1987, the scientific investigation of the field has been growing.

3.1.1. Measures of Mental Illness Stigma

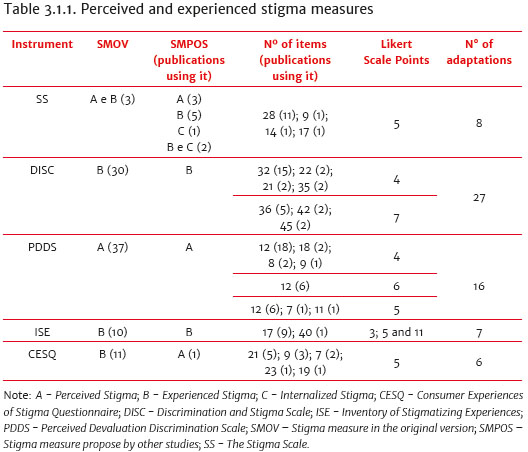

Although there is a growing body of research on this field, a major difference between the studies is the measurements used to assess MIS. We identified only five instruments with at least five citations, each showing different characteristics. All scales used a Likert variation to answer each item, and only the Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences (ISE) did not vary from the original Likert scale.

Table 3.1.1 summarizes the five instruments used for perceived and experienced MIS screening. Three were developed to assess experienced stigma: (a) Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC; Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius, & Leese, 2009), (b) ISE (Stuart, Milev, & Koller, 2005), and (c) Consumer Experiences of Stigma Questionnaire (CESQ; Wahl, 1999); one instrument was specifically designed to assess perceived stigma: Perceived Devaluation Discrimination Scale (PDDS; Link, 1987); and one assess both perceived and experienced stigma: The Stigma Scale (SS; King et al., 2007). However, some studies used the same scales for screening other types of stigma.

3.1.2 Perceived Stigma Measures

The PDDS was the first instrument created to assess perceived stigma and it seems to be the main choice of the studies that address perceived MIS. This scale has been adapted with different names and only few studies (n = 2; 5.5%) referred to the original instrument name: Link's Beliefs About Devaluation Discrimination Scale (LBADDS; Link, 1987). It is worth mentioning that we opted to use the term PDDS in this study, because it is applied by half of the included studies that used this instrument (n = 18; 50%). Another well-established term is Devaluation-Discrimination Scale -DDS (n = 7; 19.44%). Originally, the PDDS was a six-point Likert-type scale, with 12 items. In addition, all studies that used PDDS (n = 37) in our review evaluated the perceived stigma.

3.1.3 Experienced Stigma Measures

In our review, the CESQ was the first instrument developed specifically for the assessment of experienced stigma. The first version of CESQ had 21 items, evaluating stigma in a five-point Likert scale comprised of two subscales: (a) the Stigma section (items 1-12), and (b) the Discrimination section (items 13-21). Both subscales evaluated experienced stigma (Wahl, 1999). Only one of the included studies used the CESQ to evaluate perceived stigma (Bos, Kanner, Muris, Janssen, & Mayer, 2009). It should be noted that some authors refer to this instrument as the Modified Consumer Experiences of Stigma Questionnaire (MCESQ), because it uses a similar version of the scale with differences in some nomenclatures used to refer to individuals with mental illness. In the MCESQ the term "consumers" is replaced with "persons" (e.g., persons with mental illness, persons who have a psychiatric disorder; Dickerson et al., 2002; Lv, Wolf, & Wang, 2013).

The ISE has 17 items split into two subscales: (a) Stigma Impact Scale (SIS), and (b) the Stigma Experiences Scale (SES). This is the only instrument that kept its total number of items stable across different adaptations. Only one of the studies added new subscales to the ISE aiming to cover other constructs (Oleniuk, Duncan, & Temper, 2013). In the reviewed studies, the SES was used as an experienced stigma measure. On the other hand, a literature review suggests that SES covers several distinct dimensions of personal stigma, such as social withdraw, perceived and internalized stigma (Brohan, Slade, Clement, & Thornicroft, 2010).

The most cited instrument to access experienced stigma, in our review, was the DISC. It was first developed to be an internationally reliable measure of MIS. The first version had 36 items. The first 32 statements evaluated experienced stigma in a seven-point Likert scale. According to the instructions, if a discrimination score is given for one of the items, an additional statement needs to be included asking for an example. This is one remarkable difference of DISC compared to other measures of the MIS, as it includes a qualitative assessment in addition to quantitative scores. The last four items assess anticipated stigma (Thornicroft et al., 2009).

All studies reported that experienced stigma is the main construct measured by DISC. The latest version of DISC is a 32-item, four-point Likert-type scale with four subscales: (a) experienced discrimination (items 1-21); (b) anticipated discrimination (items 22-25); (c) overcoming stigma (items 26-27); and (d) positive treatment (items 28-32). Therefore, studies aiming to investigate only experienced stigma could use just the first 21 items of DISC-12 (Corker et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017).

3.1.4 Perceived and Experienced Stigma measure

Another commonly used instrument is the SS, which originally was a 28item, six-point Likert-type scale divided into 3 subscales: (a) discrimination, (b) disclosure, and (c) positive aspects. To the best of our knowledge, SS assesses both perceived and experienced stigma (King et al., 2007), however, there are disagreements among reviewed papers. Three studies suggested that SS's first sub-scale assesses only perceived stigma, while two other studies suggested it assesses both perceived and experienced stigma. One study assumed it evaluates internalized stigma, and two assumed it evaluates internalized and experienced stigma. The five remaining studies assumed that the instrument assesses only experienced stigma.

3.1.5 Variables Associated with Perceived and Experienced Stigma Scores

Other than screening for the most utilized instruments for the measurement of perceived and experienced MIS in adults, our study has also explored some of the sociodemographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric variables that may present a moderator effect (when controlled) or an intervening effect (when it is not controlled) on MIS scores. In the following sections we reported studies that described recurrent variables as influencing results for MIS, such as sex (n = 62; 61.3%); inpatient and/or outpatient samples (n = 14; 13.8%); age (n = 20; 19.8%); diagnostic (n = 31; 30.7%); and symptoms severity (n = 31; 30.7%). Sample characteristics and variables associated with the MIS scores, in each one of the studies, are summarized in Table 3.1.5.1.

3.1.6 Sex and Stigma

Most of the studies (n = 55; 54.5%) did not find significant sex differences in MIS scores. Other studies (n = 39; 38.6%) did not evaluate or did not show the analyses for possible sex differences in MIS scores. Only seven of the studies found a significant sex difference. Four of those studies found that men had higher experienced (Adeosun et al., 2014; Chalers, Manoranjitham, & Jacob, 2007; Vidojevic et al., 2012) and perceived stigma scores (Park et al., 2015). The other three studies suggested that women tend to have more experience stigma (Pawar et al., 2014; Sarkin et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2015). One of these studies had a sample of Indian women in the army. Therefore, it is possible that sex effects are related to cultural differences (Pawar et al., 2014). These findings suggested that sex may have some effect, but it is underrepresented in the literature.

3.1.7 Inpatient and Outpatient Stigma

Most studies (n = 68; 67.3%) used homogenous samples (outpatients or inpatients). Only 14 studies (13.8%) evaluated possible differences between these patients; and they found that there is no significant difference in perceived or experienced MIS scores of in and outpatients. The remaining 19 papers (18.8%) did not evaluate or did not show evidence for possible differences between in and outpatients.

3.1.8 Age Differences

More than a third of the studies did not include the elderly (65 years or older) in their sample (n = 38; 37.6%), while some studies separated older participants into a different group (n = 17; 16.8%), and others controlled for age (n = 3; 2.9%). These 20 studies (19.8%) found significant effects for age in perceived and experienced MIS scores. However, the direction of such effects is unclear, as some studies pointed out higher stigma scores among younger samples (Sarkin et al., 2014; Switaj et al., 2011; Zoppei et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2015), while others did so for elderly ones (Park et al., 2015; Vidojevic et al., 2015). Only four of the studies that included elderly participants did not control for or did not report the data related to possible age differences in their samples. The remaining studies (n = 39) did not present the age range of the sample, therefore we estimated the range based on the mean age of participants in each paper and it was found that, apparently, they also did not include the elderly in their samples.

3.1.9 Stigma and Diagnostic

Almost half of the studies (n = 49; 48.5%) had a sample population with a specific disorder, making it impossible to evaluate for possible differences between diagnostics. Among the studies that investigated diagnostic effects (n = 31; 30.7%), 21 found no significant differences. Ten studies pointed out that MIS scores were different between diagnostics and suggested that mood disorders (MD) (n = 4) present higher MIS scores when compared to schizophrenia (SZ) (Corker et al., 2014; Link, 1987; Picco et al., 2017; Wood & Irons, 2017). One study found higher MIS scores in people with SZ compared to those with MD (Sarkin et al., 2014), while another study suggested that SZ and depression have similar MIS scores (Świtaj et al., 2010). The other four studies pointed out that other mental disorders also present higher MIS (Catthoor et al., 2015; Freidl et al., 2007; Ilic et al., 2013; Verhaeghe & Bracke, 2008).

The remaining 21 studies did not control or did not report the data related to possible perceived and experienced MIS differences between diagnostics. Although studies indicated some diagnostic effects, there was no agreement as to whether a specific disorder showed more stigma than others.

3.1.10 Symptom Severity Bias

MIS literature often describes symptoms as having bias effects over measures. However, the majority of our reviewed studies (n = 70; 69.3%) did not take into consideration the severity of the symptoms. It is important to note that, regardless of the usage of a diagnostic instrument (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5), researchers did not test or report these analyzes. Among the remaining 31 (30.7%), 12 (11.8%) did not find significant associations and 19 (18.8%) reported positive associations between symptoms and stigma. In line with the assumption of symptoms severity effect, most of the researches (n = 75; 74.2%) included symptom measures. Thus, most researches indeed considered the need for inclusion of symptom measures but not always it was tested or reported in the analyses outcomes.

4. Discussion

We systematically reviewed the literature regarding the MIS field looking for trends in different methodologies. We discovered that the research in the field has been growing over time, which reinforces the need for standards and directions to achieve a solid body of evidences in a near future. We only included studies that used evaluation instruments that appeared at least five times across all studies. This strategy revealed a consistent and growing body of works restricted to five instruments. However, we identified that the use of these instruments is sometimes incongruent with the original purposes of the measure (Mizuno et al., 2017; Vass, Sitko, West, & Bentall, 2017; Wood & Irons, 2017). First, SS seems to have items that could be interpreted as an assessment of more than one type of stigma. This hypothesis may be observed, as items 11, 13, 17, and 26 showed a factor loading below 0.45 during the original validation and further adaptations (Ho et al., 2015; King et al., 2007; Mizuno et al., 2017; Morandi et al., 2013).

A similar issue occurred with CESQ, which was developed to measure experienced stigma (Wahl, 1999). Seemingly, some authors used the instrument to measure perceived stigma (Bos et al., 2009). However, there was an agreement among all of the studies, which used DISC and ISE, that these instruments primarily evaluate experienced stigma. All studies, which used PDDS, also agreed that it evaluates perceived stigma. Moreover, most of the studies used SS and CESQ, in order to assess experienced stigma. As a recommendation, we suggest future researchers to follow these lines. Such conclusion is in accordance with previous reviews (Fox et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2017).

When looking for trends in the study field of MIS, we focused on variables often described as moderator or intervening. Along these lines, the literature is repetitively suggesting bias effects on MIS due to treatment regime. Additionally, a previous systematic review found that mental health professionals who work with inpatient facilities in the Caribbean and Latin American countries reported discrimination against patients with mental illness, which could explain differences in this matter (Mascayano et al., 2016).

In our review, the studies that investigated differences between in and outpatients did not report treatment regime effects on MIS. However, less than 15% of the included studies investigated differences between in and outpatients. Therefore, conclusions should be observed with caution due to the limited number of works. However, the same results were also documented in a previous meta-analysis that aimed to investigate the relationship between internalized stigma and sociodemographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric variables with PWMI (Livingston & Boyd, 2010).

Another variable frequently investigated and assumed to have an effect on MIS scores is sex. In our study, the majority of the works reviewed indicated no such effects. We also found inconclusive age effects, regardless of the observation that age may have an impact on MIS scores (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Wong et al., 2018). Different understandings about age impacts on stigma scores were also highlighted in previous systematic reviews with conflicting results for comparisons between older and younger adults (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Wong et al., 2018). Thus, according to our and previous observations, the influence of age on the MIS scores remains unclear.

The literature also suggests that diagnostics are more commonly associated with MIS than sex, age, or the environment for people living with mental illness (Sheehan, Nieweglowski, & Corrigan, 2016; Yamaguchi et al., 2017). Typically, patients with schizophrenia are those who suffer more discrimination, according to the literature (Krupchanka & Katliar, 2016; Yamaguchi et al., 2017). However, we observed that a third of the studies in this review included only participants with schizophrenia. Indeed, these works reported high scores of MIS. Still, such high scores do not mean differences in comparison with other disorders. In fact, from all studies that compared samples of participants with schizophrenia to participants with other disorders, only one found significant results (Sarkin et al., 2014).

Contrastingly, more studies found results pointing out that participants with schizophrenia have lower MIS scores when compared to other disorders (Link, 1987; Corker et al., 2014; Picco et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2017), and one suggested that MIS scores in depression and schizophrenia are similar (Switaj et al., 2010). Therefore, most of the works considered here failed to show diagnostic effects. In this perspective, it is possible that other variables, such as symptoms severity, present more impact on perceived and experienced MIS scores than the diagnostic (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Switaj et al., 2011).

Symptoms occurring during the evaluation of stigma may contribute to MIS scores. The presence of delusions or hallucinations in psychotic patients is common, which may contribute for the patients' perceiving or reporting stigma experiences that have never occurred or that have happened in a different manner (Adeosun et al., 2014; Sarkin et al., 2014). Aligned with this assumption, most of the studies that pointed to a moderator effect between MIS and symptoms severity had included patients with psychotic symptoms (n = 13; 68%). However, other symptoms (e.g., mania and depression) may also moderate MIS scores (Nilsson, Kugathasan, & Straarup, 2016; Vázquez et al., 2011; Thomé et al., 2012). In this line, a previous meta-analysis also suggested that symptoms severity may have a moderator effect on MIS scores (Livingston & Boyd, 2010).

However, conclusions must be considered considering some limitations. It is possible that other variables not considered here have important effects on stigma scores (e.g. duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, medication effects) (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Li et al., 2017; Picco et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Some studies also indicated marital status, education level, and race as other important secondary variables (Rayan et al., 2017; Townley et al., 2017). Hence, future research should address these issues and also evaluate for associations with other types of stigma that have not been yet studied (e.g., anticipated stigma).

Another possible limitation of our study is the inclusion of instruments that were used at least five times. Due to this criterion, we may not have included newer instruments. In summary, our review highlighted five instruments of perceived and experienced MIS assessment with a solid literature background. However, it is necessary great attention to how sociodemographic, psychosocial, and psychiatric variables may moderate their scores, especially when considering age and symptoms severity. Likewise, it allowed us to give initial support for assuming that age and symptoms severity may be some of the most important intervenient variables of the MIS.

To precisely measure the MIS, it is essential that healthcare providers are aware of the variables that may present an intervening effect on instruments scores. Besides, these results may be useful for researchers to consider adopting a common understanding about the terminologies in this field. We also recommend that new researches aim to adapt and validate the instruments presented in this review for new contexts, rather than creating new ones that evaluate the same constructs. It should be noted that Brazil needs new instruments to measure the perceived and experienced MIS. Therefore, cross-cultural adaptation studies are recommended to address this issue and to contribute with the Brazilian National Agenda for Health Research Priorities.

References

Adeosun, I. I., Adegbohun, A. A., Jeje, O. O., & Adewumi, T. A. (2014). Experiences of discrimination by people with schizophrenia in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Public Mental Health, 13(4),189-196. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-06-2013-0038 [ Links ]

Bos, A. E. R., Kanner, D., Muris, P., Janssen, B., & Mayer, B. (2009). Mental illness stigma and disclosure: Consequences of coming out of the closet. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(8),509-513. doi: 10.1080/01612840802601382 [ Links ]

Bos, A. E., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1),1-9. doi: 10.1080/019 73533.2012.746147 [ Links ]

Brasil. (2015). Agenda Nacional de Prioridades de Pesquisa em Saúde. Retrieved from http://brasil.evipnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/ANPPS.pdf [ Links ]

Brohan, E., Slade, M., Clement, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: A review of measures. Health Services Research, 10(80). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-80 [ Links ]

Catthoor, K., Schrijvers, D., Hutsebaut, J., Feenstra, D., & Sabbe, B. (2015). Psychiatric stigma in treatment-seeking adults with personality problems: Evidence from a sample of 214 patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6(101),1-6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00101 [ Links ]

Charles, H., Manoranjitham, S. D., & Jacob, K. S. (2007). Stigma and explanatory models among people with schizophrenia and their relatives in Vellore, South India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 53(7),325-332. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074538 [ Links ]

Corker, E. A., Beldie. A., Brain, C., Jakovljevic, M., Jarema, M. ... Thornicroft, G. (2014). Experience of stigma and discrimination reported by people experiencing the first episode of schizophrenia and those with a first episode of depression: The FEDORA project. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(5),438-445. doi: 10.1177/0020764014551941 [ Links ]

Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., & Barr, L. (2006). The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(8),875-884. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875 [ Links ]

Dickerson, F. B., Sommerville, J., Origoni, A. E., Ringel, N. B., & Parente, F. (2002). Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 28(1),143-155. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12047014 [ Links ]

Fox, A. B., Earnshaw, V. A., Taverna, E., & Vogt, D. (2017). Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma and Health, 3(4),348-376. doi: 10.1037/sah0000104 [ Links ]

Freidl, M., Spitzl, S. P., Prauser, W., Zimprich, F., Lehner-Baumgartner, E., Baumgartner, C., & Aigner, M. (2007). The stigma of mental illness: Anticipation and attitudes among patients with epileptic, dissociative or somatoform pain disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(2),123-129. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278879 [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1988). Estigma: notas sobre a manipulação da identidade deteriorada. 4. ed. São Paulo: LTC. [ Links ]

Ho, A. H. Y., Potash, J. S., Fong, T. C. T., Ho, V. F. L., Chen, E. Y. H.... Ho, R. T. H. (2015). Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the Stigma Scale: examining the complex experience of stigma and its relationship with self-esteem and depression among people living with mental illness in Hong Kong. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 56,198-205. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.016 [ Links ]

Ilic, M., Reinecke, J., Bohner, G., Röttgers, H-O., Beblo, T., Driessen, M., Frommberger, U., & Corrigan, P. W. (2013). Belittled, avoided, ignored, denied: Assessing forms and consequences of stigma experiences of people with mental illness. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1),31-35. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.746619 [ Links ]

King, M., Dinos, S., Shaw, J., Watson, R., Stevens, S., Passetti, F. ... Serfaty, M. (2007). The Stigma Scale: Development of a standardised measure of the stigma of mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(3),248-254. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638 [ Links ]

Krupchanka, D., & Katliar, M. (2017). The role of insight in moderating the association between depressive symptoms in people with schizophrenia and stigma among their nearest relatives: A pilot study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(3),600-607. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw024 [ Links ]

Lacey, M., Paolini, S., Hanlon, M. C., Melville, J., Galletly, C., & Campbell, L. E. (2014). Parents with serious mental illness: Differences in internalised and externalised mental illness stigma and gender stigma between mothers and fathers. Psychiatry Research, 225(3),723-733. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.010 [ Links ]

Lai, H. M. X., Cleary, M., Sitharthan, T., & Hunt, G. E. (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990-2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154(1),1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.031 [ Links ]

Li, J., Guoa, Y-B., Huanga, Y-G., Liua, J-W., Chenb, W... & Thornicrofte, G. (2017). Stigma and discrimination experienced by people with schizophrenia living in the community in Guangzhou, China. Psychiatry Research, 255,225-231. doi: 10.1016/j. psychres.2017.05.040 [ Links ]

Link, B. G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52(1),96-112. doi: 10.2307/2095395 [ Links ]

Livingston, J. D., & Boyd, J. E. (2010). Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 71(12),2150-2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030 [ Links ]

Lv, Y., Wolf, A., & Wang, X. (2013). Experienced stigma and self-stigma in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(1),83-88. doi: 10.1016/j. genhosppsych.2012.07.007 [ Links ]

Mascayano, F., Tapia, T., Schilling, S., Alvarado, R., Tapia, E., Lips, W., & Yang, L. H. (2016). Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 38(1),73-85. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1652 [ Links ]

Mizuno, M., Yamaguchi, S., Taneda, A., Hori, Hiroaki., Aikawa, A., & Fujii, C. (2017). Development of Japanese version of King's Stigma Scale and its short version: Psychometric properties of a selfstigma measure. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(3),189-197. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12470 [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med, 6(7),1-6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [ Links ]

Morandi, S., Manetti, S. G., Zimmermannb, G., Favroda, J., Chanachevd, A., Monnata, M., & Bonsackaa, C. (2013). Mesurer la stigmatisation perçue chez les personnes souffrant de troubles psychiques: traduction française, validation et adaptation de la Stigma Scale. L'Encéphale, 39(6),408-415. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2013.03.002 [ Links ]

Nilsson, K. K., Kugathasan, P., & Straarup, K. N. (2016). Characteristics, correlates and outcomes of perceived stigmatization in bipolar disorder patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 194,196-201. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.025 [ Links ]

Oleniuk, A., Ducan, C. R., & Tempier, R. (2013). The impact of stigma of mental illness in a Canadian community: A survey of patients experiences. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(1),127-132. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9453-2 [ Links ]

Olofsson, H., Brolund, A., Hellberg, C., Silverstein, R., Stenström, K., Österberg, M., & Dagerhamn, J. (2017). Can abstract screening workload be reduced using text mining? User experiences of the tool Rayyan. Research Sythesis Method, 8(3),275-280. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1237 [ Links ]

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(210),1-10 doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [ Links ]

Pawar, A. A., Peters, A., & Rathod, J. (2014). Stigma of mental illness: A study in the Indian Armed Forces. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 70(4),354-359. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.07.008 [ Links ]

Picco, L., Lau, Y. W., Pang, S., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Mediating effects of self-stigma on the relationship between perceived stigma and psychosocial outcomes among psychiatric outpatients: findings from a cross-sectional survey in Singapore. BMJ open, 7(8),1-10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen2017-018228 [ Links ]

Rayan, A., Mahroum, M. H., Khasawneh, A. (2017). The correlates of stigma toward mental illness among Jordanian patients with major depressive disorder. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 54(2),192-197. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12222 [ Links ]

Sarkin, A., Lale, R., Sklar, M., Center, K. C., Gilmer, T., Fowler, C. ... Ojeda, V. D. (2014). Stigma experienced by people using mental health services in San Diego County. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(5),747-756. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0979-9 [ Links ]

Sheehan, L., Nieweglowski, K., & Corrigan, P. (2016). The Stigma of Personality Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(11), 1-7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0654-1 [ Links ]

Stuart, H., Milev, R., & Koller, M. (2005). The Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences: Its development and reliability. World Psychiatry, 4(1),35-39. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285795492_The_Inventory_of_Stigmatizing_Experiences_Its_development_and_reliability [ Links ]

Switaj, S., Wciórka, J., Grygiel, P., Smolarska-Switaj, J., Anczewska, M., & Chrostek, N. (2010). Częstość doświadczeń stygmatyzacji u chorych na schizofrenięw porównaniu do pacjentów z innymi problemami zdrowotnymi. Postępy Psychiatrii i Neurologii, 19(4),269-274. Retrieved from http://www.ppn.ipin.edu.pl/archiwum/2010-zeszyt-4/czestosc-doswiadczen-stygmatyzacji-u-chorych-na-schizofrenie-w-porownaniu-do-pacjentow-z-innymi-problemami-zdrowotnymi.html [ Links ]

Switaj, S., Wciórka, J., Grygiel, P., Smolarska-Switaj, J., Anczewska, M., & Grzesik, A. (2011). Experience of stigma by people with schizophrenia compared with people with depression or malignancies. The Psychiatrist, 35(4),135-139. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.110.029579 [ Links ]

Thomé, E. S., Dargél, A. A., Migliavacca, F. M., Potter, W. A., Jappur, D. M. C., Kapczinski, F., & Ceresér, K. M. (2012). Stigma experiences in bipolar patients: The impact upon functioning. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(8),665-671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01849.x [ Links ]

Thornicroft, G., Brohan, E., Rose, D., Sartorius, N., & Leese, M. (2009). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet, 373(9661),408-415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08) 61817-6 [ Links ]

Townley, G., Brusilovskiy, E., & Salzer, M. S. (2017). Urban and non-urban differences in community living and participation among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Social Science & Medicine, 177,223-230. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.058 [ Links ]

Vázquez, G. H., Kapczinski, F., Magalhaes, P. V., Córdoba, R., Jaramillo, C. L. ... Tohen, M. (2011). Stigma and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1-2),323-327. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.012 [ Links ]

Vass, V., Sitko, K., West, S., & Bentall, R. P. (2017). How stigma gets under the skin: The role of stigma, self-stigma and self-esteem in subjective recovery from psychosis. Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches, 9(3),235-244. doi: 10.1080/1752243 9.2017.1300184 [ Links ]

Verhaeghe, M., & Bracke, P. (2008). Ward features affecting stigma experiences in contemporary psychiatric hospitals: A multilevel study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(5),418-428. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0314-4 [ Links ]

Vidojević, I. M., Jočić, D. D., Tošković, O. (2012). Comparative study of experienced and anticipated stigma in Serbia and the world. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4)355-361. doi: 10.1177/0020764011399000

Wahl, O. F. (1999). Mental Health Consumers' Experience of Stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 25(3),467-478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394 [ Links ]

Wei, Y., McGrath, P., Hayden, J., & Kutcher, S. (2017). The quality of mental health literacy measurement tools evaluating the stigma of mental illness: A systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(5),433-462. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000178 [ Links ]

Wong, E. C., Collins, R. L., Cerully, J. L., Yu, J. W., & Seelam, R. (2018). Effects of contact-based mental illness stigma reduction programs: Age, gender, and Asian, Latino, and White American differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(3),299-308. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1459-9 [ Links ]

Wood, L., & Irons, C. (2017). Experienced stigma and its impacts in psychosis: The role of social rank and external shame. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(3),419-431. doi: 10.1111/papt.12127 [ Links ]

Yamaguchi, S., Mizuno, M., Ojio, Y., Sawada, U., Matsunaga, A., Ando, S., & Koike, S. (2017). Associations between renaming schizophrenia and stigma-related outcomes: A systematic review. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(6),347-362. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12510 [ Links ]

Zoppei, S., Lasalvia, A., Bonetto, C., Bortel, T. V., Nyqvist, F., & Thornicroft, G. (2014). Social capital and reported discrimination among people with depression in 15 European countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(10),1589-1598. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0856-6 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nicolas de Oliveira Cardoso

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Prédio 11, Sala 930, Av. Ipiranga, 6681, Partenon

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. CEP: 90619-900

E-mail: nicolas.deoliveira@hotmail.com

Submission: 16/04/2019

Acceptance: 15/10/2019

This study was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Finance Code 001.

Authors note

Nicolas de O. Cardoso, Department of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS); Breno Sanvicente-Vieira, Department of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ); Isabela De M. V. Ferracini, Department of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS); Irani Iracema de L. Argimon, Department of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS)