Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Psicologia: teoria e prática

Print version ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.24 no.1 São Paulo Jan./Apr. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPPA14041.en

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Adaptation and initial psychometric evidence of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale

Adaptação e evidências psicométricas iniciais da escala Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale

Adaptación y evidencia psicométricas iniciales de la Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale

Alexsandro Luiz de AndradeI ; Gabriela TechioII

; Gabriela TechioII ; Clarissa E. CoriolanoI

; Clarissa E. CoriolanoI ; Manoela Z. de OliveiraII

; Manoela Z. de OliveiraII

IDepartment of Postgraduate Studies in Public Management, Federal University of Espírito Santo (Ufes)

IIPostgraduate Program in Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS)

ABSTRACT

Work-family conflict shows tension between professional and family life domains, with negative repercussions for job performance, satisfaction with life and family. This study sought to adapt and gather initial psychometric evidence from the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC) in Brazil. The participants were 229 adults, active in the labor market, and involved in family relationships. Exploratory factor analysis procedures yielded positive initial evidence of the validity of internal, external, and precision structure, attesting in favor of its use in Brazil. The final version of the WFBRC distinguished two dimensions: work interfering with family (15 items; α and ω = 0.90) and family interfering with work (15 items; α = 0.90 and ω = 0.89). Results indicate convergent and discriminant validity between the WFBRC and conflict perception, as well as work-family enrichment. The conclusion is that the instrument is adequate and can contribute theoretically to investigations and work-family conflict-related practices.

Keywords: professional development, psychometrics, work-family conflict, family, psychometric scales

RESUMO

Conflito trabalho-família evidencia tensionamento entre domínios da vida profissional e familiar, com repercussões negativas para a performance no trabalho e satisfação com a vida e família. Este estudo procurou adaptar e levantar evidências psicométricas iniciais da Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC) no Brasil. Participaram 229 adultos, ativos no mercado de trabalho e envolvidos em relações familiares. Procedimentos de análise fatorial exploratória resultaram em evidências iniciais positivas de validade de estruturas interna e externa e precisão, atestando a favor de seu uso no Brasil. A versão final da WFBRC discriminou duas dimensões: trabalho interferindo na família (15 itens; α e ω = 0,90) e família interferindo no trabalho (15 itens; α = 0,90 e; ω = 0,89). Evidências convergentes e discriminantes da WFBRC com medidas de percepção de conflito e enriquecimento trabalho-família foram apresentadas. Conclui-se que o instrumento é adequado e pode contribuir teoricamente com investigações e práticas relativas ao conflito trabalho-família.

Palavras-chave: desenvolvimento profissional, psicometria, conflito trabalho-família, família, escalas psicométricas

RESUMEN

Conflicto trabajo-familia evidencia tensión entre dominios de vida profesional y familiar, con repercusiones negativas para desempeño laboral, satisfacción con la vida y la familia. Este estudio buscó adaptar y presentar evidencia psicométricas iniciales de la Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC) en Brasil. Participaron 229 adultos, activos en el mercado laboral e involucrados en relaciones familiares. El análisis factorial exploratorio resulto en evidencias iniciales positivas de validez de la estructura interna, externa y de precisión, indicando adecuación de uso en Brasil. La versión final del WFBRC distinguió dos dimensiones: trabajo interfiriendo con la familia (15 ítems; α y ω = 0,90) y familia interfiriendo con el trabajo (15 ítems; α = 0,90 y; ω = 0,89). Se presentó evidencia convergent y discriminatoria de la WFBRC con medidas de percepción de conflicto y enriquecimiento trabajo-familia. Se concluye que el instrumento es adecuado y puede contribuir teóricamente, con investigaciones, y prácticas relativas al conflicto trabajo-familia.

Palabras clave: desarrollo profesional, psicometría, conflicto trabajo-familia, familia, escalas psicométricas

There is constant interaction between the roles people play at work and within the family, requiring individuals to deal with the demands and responsibilities arising from both domains (Kossek & Lee, 2017), meeting different and often conflicting expectations (Powell et al., 2018).

Work-family conflict is known to be bidirectional (Kossek & Lee, 2017). One direction refers to work interfering with the family (Work-family conflict - WFC), which occurs when individuals are involved and busy with work tasks when they are with their families. The other direction refers to family-work conflict (FWC), when work responsibilities are postponed due to family issues (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013).

According to Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), the aspects of bidirectional conflicts include three antecedents present in the WFC and FWC domains: time, strain, and behavior. Time-based conflicts occur when a significant amount of time is devoted to one of the domains and individuals cannot meet the demands of the other. For example, professionals dealing with many tasks and working overtime are more likely to experience this type of conflict (Sevä & Öun, 2015). In turn, strain-based conflicts occur when concerns, irritability, and stress arising in one domain affects one's performance in the other domain. One example is working individuals responsible for assisting their families, resulting in overloads and fatigue (Vilela & Lourenço, 2018). Finally, Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) explain that behavior-based conflicts occur when work and family present incompatible behavioral patterns. For instance, competitiveness encouraged in the job market is undesirable in family relationships.

The negative impacts arising from interferences between these domains are discussed in the literature. The following impacts stand out: disinvestment in one's professional role to devote time to the family (Young & Schieman, 2017); the marital relationship is harmed because less time is invested in the relationship (Haslam et al., 2014); and a feeling of missing out on the children's development because of an intense work routine (Rehman & Khan, 2018). There are also consequences at an individual level when people have less time to invest in themselves and their health (Grönlund & Javornik, 2014), resulting in illnesses (Rocco et al., 2019).

Despite these adverse impacts, the possibility of playing multiple roles in different domains of life and the meanings individuals assign to these roles are essential for an individual's self-concept (Lassance & Sarriera, 2009). For this reason, it is vital to understand the relationships between these roles. Because work and family are two of the main domains in which adult individuals participate, and the roles played in these domains tend to be very relevant, different instruments have been developed to access family-work conflict in all its complexity (directions and bases) (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Carlson et al., 2000). However, most instruments fail to address some of these constitutive theoretical aspects, or the adaptation of these instruments across cultures presented unsatisfactory psychometric properties, such as in Brazil (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013, 2019).

Netemeyer et al. (1996) conducted one of the first studies developing instruments to access these two dimensions of conflict considering three directions. First, based on the literature, the authors established the work-family conflict (WFC) and family-work conflict (FWC) dimensions and developed the Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict Scales. From the 110 items initially proposed, 18 remained in the instrument to measure the general aspects of WFC and 18 to measure FWC; 20 items to assess time-based WFC and 19 items to assess strain-based WFC; 19 items to assess time-based FWC and 16 items to measure strain-based FWC. Second, after performing various procedures to analyze and improve the measure, a less theoretically complex final version composed of 10 items (five to assess FWC and five for WFC) remained, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.83 to 0.89. Finally, Aguiar and Bastos (2013) translated and adapted this scale to assess work-family conflict in the Brazilian context. Despite the positive results, the authors highlight that the translated and validated version did not saturate all the aspects of the theoretical model used to understand work-family conflict because it comprises only the general demands of each domain (time and strain), disregarding the behavioral component of the work-family conflict.

Given the original instrument's limitations, Carlson et al. (2000) developed a measure to saturate all the elements presented in the theoretical model proposed by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985). The authors conducted three studies, from which a new instrument resulted (Multidimensional Measure of Work-Family Conflict). Its development involved a theoretical review, the development and selection of items for the scales based on other studies, an expert panel, and factor procedures in order to obtain psychometric evidence. The final instrument comprises the six theoretical dimensions proposed by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985). Aguiar and Bastos (2019) adapted the instrument addressing a sample of 446 Brazilian workers and presented a measure with an internal and theoretical structure different from the original, supported on a two-dimension structure favoring the six-dimensions structure.

Hence, the measures available to assess work-family conflict traditionally assess subjective dimensions at the expense of behavioral and objective aspects (e.g., "The demands of my work interfere with my family life"). For example, this is a characteristic of the Work-Family Conflict Scale (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013; Netemeyer et al., 1996) and the Multidimensional Work-Family Conflict Scale (Carlson et al., 2000; Aguiar & Bastos, 2019). However, the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale (WFBRC) (Clark et al., 2019) was intended to overcome this limitation.

The WFBRC is a checklist developed in the United States to assess the objective and behavioral aspects of the tension between work and family roles (Clark et al., 2019). Its original and simplified structure is composed of two dimensions: a) Behavioral work interference with family (WIF), which assesses work behaviors and negative situations affecting personal life, such as lack of time to spend with family issues when facing stress at work; and b) Behavioral family interference with work (FIW), which refers to events and contexts that negatively affect job performance, such as not fulfilling work obligations to meet family demands.

The Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict development involved four independent studies (Clark et al., 2019). The first concerned the development of items that resulted from a preliminary list of 82 items assessed in focal groups addressing a group of professionals. The second study was an empirical study intended to develop the scale and verify its construct validity, from which a 30-item inventory resulted (15 WIF and 15 FIW), with items rated on a five-point Likert scale (from never to very frequent) and Cronbach's alpha above 0.93. A third study reports convergent validity between the work-family conflict dimensions of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict and the measures proposed by Netemeyer et al. (1996) and Carlson et al. (2000) to assess perceptions of work-family conflict; Pearson's correlations were positive and ranged from 0.25 and 0.70. Finally, the fourth study assessed incremental validity. The results indicated that both dimensions (WIF and FIW) predicted burnout, turnover, depression, and psychological strain (Clark et al., 2019).

Considering the growing relevance of studies addressing work-family conflict for individuals, families, organizations, public policies (Allen et al., 2020; Collins, 2019) and the new demands and impact of the world of work on individuals' different life domains (Blustein & Guarino, 2020), this study's objective was to adapt and verify the validity of the Brazilian version of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC). Other motivations for this study concern a lack of measures adapted for the Brazilian context (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013, 2019) and the fact that the original studies that developed these measures were published a long time ago (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Carlson et al., 2000). Hence, there is a need to present a psychometrically and theoretically updated instrument to assess the new theoretical and practical nuances of work-family conflict.

Method

Participants

A total of 229 Brazilian adult individuals participated in this study. Of these, 182 were women (795%), and 47 were men (20.5%). Most participants were from the southeast (N = 132), followed by the south (N = 65) and north (N = 23). Most were aged between 21 and 29 (N = 53), followed by 30 and 39 years old (N = 57). Graduate studies (N = 121) were the most predominant educational level, followed by college degree (N = 54), high school (N = 45), and middle school (N = 9). Concerning having children, most participants reported having no children (N = 104); (N = 63) reported having one child, and (N = 62) did not answer this question.

Cross-cultural adaptation procedures

The adaptation process of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale complied with the guidelines provided by the International Test Commission (ITC, 2017) and the methodological recommendations concerning measures and psychological assessments to adapt instruments across cultures (Borsa et al., 2012). Therefore, the first step involved asking permission from the original instrument's author to adapt the instrument to the Brazilian context (Malissa A. Clark) (Clark et al., 2019).

Afterward, two independent translators translated the 30 items from the WFBRC into Portuguese, and the authors assessed its final structure in Portuguese. A preliminary synthesis was developed and five participants, randomly selected, assessed potential comprehension issues (i.e., "Eu me envolvo menos nas conversas da família quando o trabalho exige muito de mim" [I am less engaged in my family conversations when work is too demanding]) and suggested changes in the final version ("Eu me envolvo menos "com assuntos" da família quando o trabalho exige muito de mim" [I am less engaged in my family's "matters" when work is too demanding]). Finally, the final instrument was applied with other psychometric scales to collect data.

Instruments

The participants answered a form addressing sociodemographic data to characterize the sample and the psychological instruments. The instruments are described in detail below.

• Work-family conflict scale (Netemeyer et al., 1996), which was adapted by Aguiar and Bastos (2013) to the Brazilian context. This ten-item version is rated on a six-point Likert scale (from 1 - completely disagree to 6 - completely agree) and is a two-dimension scale composed of work-family conflict (WFC - 5 items, α = 0.90, "Por causa das demandas do meu trabalho, não consigo fazer as coisas que quero fazer em casa" [Because of my job's demands, I cannot do the things I want at home]); and family-work conflict (FWC - 5 items, α = 0.85, "Eu preciso adiar atividades de trabalho por causa de demandas que surgem no tempo em casa" [I need to postpone work tasks because of demands that arise at home]).

• Work-family enrichment scale (Carlson et al., 2006). This scale was adapted to the Brazilian context and comprises ten items rated on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 - strongly disagree to 5 - strongly agree) (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2016). It addresses work-family enrichment (WFE- 5 items; α = 0.90; e.g., "Meu envolvimento com meu trabalho me deixa alegre e isso me ajuda a ser um membro melhor da família" [My involvement with my work makes me happy and it helps me be a better family member]); and family-work enrichment (WFE- 5 items; α = 0.90; e.g., "envolvimento com minha família me ajuda a ampliar meu conhecimento sobre coisas novas e isso me ajuda a ser um trabalhador melhor" [being involved with my family helps me broaden my knowledge about new things and helps me be a better worker]).

• Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale (Clark et al., 2019). Instrument adapted in this study and rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 - strongly disagree to 5 - strongly agree).

Data collection procedures

This study is part of a project previously assessed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (CAAE 15422119.2.0000.5542). The participants were recruited through a personalized invitation disseminated on social media between December 2019 and March 2020. All the individuals who answered the private messages sent by the author received clarification regarding the study's nature and objective and were asked whether they were interested and available to participate. All those who consented received a link to the online form. The first page of the form contained instructions and a free and informed consent form that could be downloaded. The average response time was 15 minutes.

Data analysis procedures

Data were first assessed in terms of missing and discrepant data. We also verified whether the response time exceeded 30 minutes. This criterion was adopted to indicate a lack of commitment or difficulty in answering the questionnaire. Twenty respondents were excluded from the remaining stages (15 for not completing the questionnaire and five for taking more than 30 minutes to complete the questionnaire). These respondents did not present differences from the remaining sample in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. Next, psychometric tests were performed to find evidence of the internal structure of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale using the Factor 10.1 software (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2017). At this stage, the Hull method (Comparative Fit Index) (Lorenzo-Seva et al., 2011) was used with exploratory factor analysis (polychoric matrices), Unweighted Least Squares (ULS), and Promin rotation to analyze the scale's dimensional structure. In addition, precision scores such as Cronbach's alpha and coefficient omega were estimated (Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016).

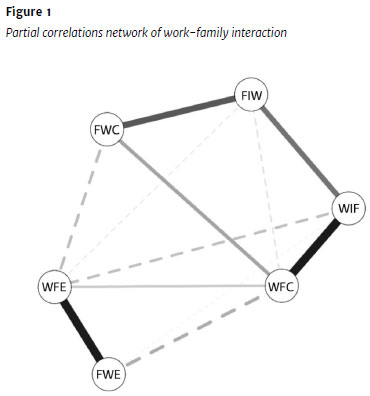

A graphic partial correlation analysis (network analysis) was performed to assess convergent and discriminant aspects (Dalege et al., 2017). According to the analysis, the thickness of the lines represents the degree of association between the variables; thicker lines indicate stronger relationships, and thinner ones indicate less intense relationships (Machado et al., 2015). In this study, dotted lines represent negative relationships (discriminant evidence), and continuous lines represent positive relationships (convergent evidence) (Figure 1).

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

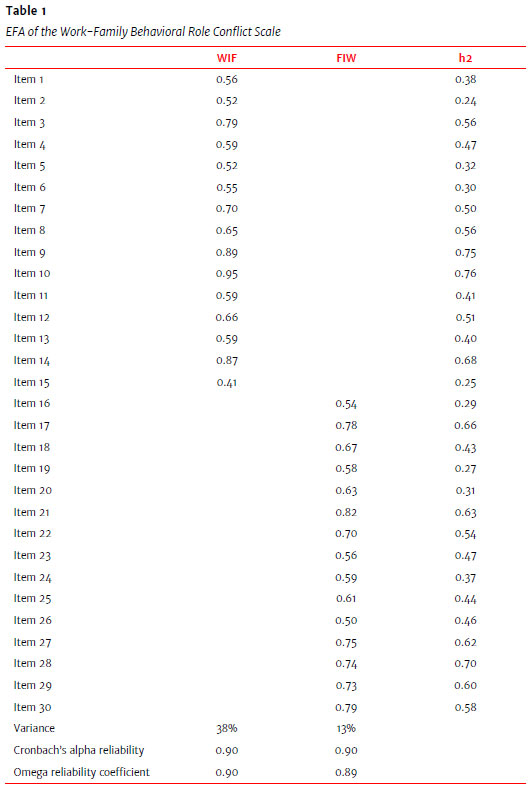

First, the resulting data matrix was assessed to perform the exploratory factor analysis, which presented positive and adequate values, with KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) equal to 0.83 and a significant Bartlett's test (x2 = 2511.7 for p < 0.000). The Hull method was used to decide on the best structural dimensional configuration and indicated a two-factor solution (GFI = 0.41; df = 371; and CAF = 2.576*), which converged with the two-dimension model of the scale (Clark et al., 2019). The bi-factor model fit indices obtained with the EFA were all high and adequate, with CFI and NNFI equal to 0.98 [C.I = 0.98-0.99], RMSEA equivalent to 0.04 [C.I = 0.01-0.05] and an AGFI of 0.96 [C.I = 0.96-0.98]. The results from the factor analysis of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale and the remaining results from the EFA are presented in Table 1.

Factor 1 assessed the dimension behavioral work interference with family (WIF) and included 15 items adapted to the Brazilian context. This factor grouped items associated with negative impact on self-care (e.g., "Meu sono é mais agitado quando minha carga de trabalho está pesada" [My sleep is more restless when my workload is heavy]) and social familial interactions (e.g., "Eu me envolvo menos 'com assuntos' da família quando o trabalho exige muito de mim" [I am less engaged in my family's "matters" when work is too demanding]). The dimension's final precision was adequate, presenting equal Cronbach's alpha and Omega coefficients of 0.90.

The second factor, family behavior interfering with work (FIW), was also composed of items congruent with the scale's original version. The items included family behaviors that affect work performance (e.g., "Eu levo muito mais tempo para completar minhas tarefas no trabalho quando estou estressado com assuntos familiares" [I take significantly longer than usual to complete routine work tasks when I am stressed from family issues], interaction with colleagues (e.g., "Eu converso menos com meus colegas de trabalho quando estou preocupado(a) com questões familiares" [I talk less with my colleagues at work when I am preoccupied with family issues]), and self-care (e.g., "Eu me preocupo menos com minha aparência no trabalho quando minha vida familiar está estressante" [I care less about my appearance at work if my family life is stressful]). Additionally, the FIW's precision indicators were adequate, presenting Cronbach's alpha equal to 0.90 and Omega coefficient equal to 0.89.

Network Analysis, Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The network analysis presented in Figure 1 shows that the dimension behavioral work interference with family (WIF), of the WFBRC, presented a high and positive association with work-family conflict (WFC) (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), with convergent validity between the different measures and the construct behavioral work interference with family. However, the discriminant validity between WIF and WFE was not significant (r = -0.24, p = 0.10).

The dimension behavioral family interference with work, of the WFBRC, converged with the parallel family-work conflict dimension (r = 0.44, p < 0.001), although no discriminant and significant evidence was found with family-work enrichment (FWE) (r = -0.04, p = 0.80). Based on the instrument adapted in this study, positive relationships were also found between both dimensions of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale (r = 0.38, p < 0.001). Figure 1 presents the network analysis between the constructs investigated in this study.

Discussion

This study presents initial evidence of the internal and external structures (convergent validity) of the Brazilian version of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC). The instrument was adequate to a two-dimension work-family conflict model (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). The final version comprised 15 items for work interfering with family (WIF) and 15 items for family interfering with work (FIW), similar to its original version (Clark et al., 2018). This study's results show that WFBRC also presented empirical and theoretical convergence with the work-family conflict measure (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013; Netemeyer et al., 1996), in addition to divergent relationships, although not significant, with the dimensions of the work-family enrichment (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2016).

The Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict is an important methodological and theoretical option for researchers to assess work and family interactions. The characteristics of the measure enable to more objectively investigate why individuals invest less in their work to benefit their families (Young & Schieman, 2017), enable a concrete analysis of the work demands that lead to worsened marital quality (Haslam et al., 2014), and facilitate the understanding of the aspects of daily work that affect time devoted to children (Rehman & Khan, 2018), also expanding knowledge of the specific behavioral causes that restrict the time invested in self-care and health (Grönlund & Javornik, 2014; Rocco et al., 2019).

As highlighted by Clark et al. (2019), the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict is an instrument that innovates the assessment of work-family conflicts. Its development process sought to highlight specific behaviors that give rise to conflicts (e.g., "Eu me envolvo menos nas conversas da família quando o trabalho exige muito de mim" [I am less engaged in my family conversations when work is too demanding]), instead of subjective items that focus on sources of stress (e.g., "As demandas de meu trabalho interferem na minha vida familiar" [The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life]), aspects that other measures focus on (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013, 2019; Carlson et al., 2000; Netemeyer et al., 1996). The WFBRC's structure overcomes the difficulties appointed by Aguiar and Bastos (2013) regarding behavioral aspects in the work-family conflict scale. Therefore, the WFBRC enables a more ideographical analysis of biases of overlapping roles between work and family, favoring a more specific understanding of everyday behavioral problems, including those related to physiological (sleep) and marital aspects (talking about problems), and everyday tasks (forgetting to pay the bills).

There is a consensus in the literature on the bidirectional nature of work-family conflicts (Kossek & Lee, 2017), and there is also a considerable amount of evidence regarding measures able to assess the phenomenon using this two-dimensional structure (work interfering with the family and family interfering with work ) (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013; Netemeyer et al., 1996). However, according to Greenhaus and Beutell's (1985), theoretical proposition, in addition to the bidirectional aspect, a measure intending to assess work-family conflicts should also discriminate three dimensions per domain (time, strain, and behavior). The internal structure of the measures available thus far has been a recurrent limitation (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013; Carlson et al., 2000). The WFBRC, from its development (Clark et al., 2018) up to the adaptation conducted in this study, reinforces that the parsimonious two-dimension structure can provide meaningful contributions to the work-family conflict, as it happened with other instruments adapted across cultures (De Andrade et al., 2017, 2018), in undergraduate training (De Andrade et al., 2019; Westring & Ryan, 2011), in a hospital context (De Andrade et al., 2020), and with executives (Braun et al., 2019).

The results from the network analysis and Pearson's correlation (r), presented in Figure 1, reinforce the theoretical relationships provided in the literature and the WFBRC development process (Clark et al., 2018; Gabardo-Martins et al., 2016; Powell & Greenhaus, 2006), corroborating the instrument's external validity. The behavioral conflict dimensions of the WFBRC obtained moderate to strong positive correlations with the conflict dimensions of the scale already adapted to the Brazilian context (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013). Even though the relationships between the WFBRC's dimensions and the work-family enrichment were not significant, a negative connection was found between the constructs and their measures (enrichment X conflict), represented in the lines in the network analysis, suggesting discrimination between the constructs which, in general, reinforce the new instrument's external evidence (discriminant).

Future studies can obtain additional evidence of validity for the WFBRC, including invariance tests according to sex (Damásio, 2013), and correlating other work (e.g., job satisfaction, intention to quit the job) and non-work domains (e.g., subjective wellbeing, marital satisfaction, etc.). Clark et al. (2019) highlight an important aspect proposed for the instrument; WFBRC was intended to present more significant and additional evidence than common work-family conflict measures. This aspect is an important contribution because, in addition to filling a gap reported by previous studies, which did not discriminate behaviors as sources of conflict between work and family, it can provide new insights regarding the phenomenon.

Future studies are needed to confirm the WFBRC's factor structure found in this investigation and to use it to expand and assess sociodemographic specificities. The study's sample size and profile did not allow for these analyses. More specifically, it allowed verifying good psychometric evidence; however, the sample's small size and restricted sociodemographic diversity made it impossible to analyze relationships between sex and work-family conflict or whether the individual had children and work-family conflict.

Finally, studies and interventions addressing the aspects interacting with work and family are relevant for individuals and organizations (Allen et al., 2020; Collins, 2019; Kossek & Lee, 2017). In this sense, the Brazilian adaptation of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict (WFBRC) presents an updated and important resource to assess individuals and collectives regarding stress and harm caused by work-family tensions. As already known, some populations of professionals are more vulnerable to work-family conflict than others, for instance, those working with public security and healthcare (De Andrade et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2019). Hence, these and other professional groups more frequently need to obtain health and wellbeing diagnoses, including information regarding the quality of interaction between roles, which should be addressed by development and people management policy programs (including, but not restricted to, those concerning allocation and remuneration) (Braun et al., 2019). Note that these interventions' objective should be to decrease conflicts between family and work, not the work itself (Nauman et al., 2020).

Assessments using the WFBRC can also be necessary for the practice of career advisors, especially when their clients are facing job insecurity (i.e., have a precarious job, are unemployed, or in a context of rising unemployment, or facing mergers or corporate acquisitions). The theoretical and inclusive perspective of Work Psychology indicates a need to investigate and develop appropriate strategies to deal with individuals in the situations described earlier, considering the numerous consequences to one's professional and personal life (Blustein & Guarino, 2020). The literature shows that job insecurity tends to negatively impact individual and familiar wellbeing (Nauman et al., 2020) and may compromise the role workers play within their families (Wayne et al., 2017). This relationship further aggravates in times of recession, when there are few or precarious alternatives to formal employment and the social security system does not support unemployed individuals (Nauman et al., 2020). The identification of behaviors that may harm work and family can support the selection or development of strategies intended to reconcile the demands of both (Matias & Fontaine, 2014) and devise a professional reallocation plan when professionals find it impossible to reconcile demands and ensure good wellbeing for themselves and their families.

References

Aguiar, C. V. N., & Bastos, A. V. B. (2013). Tradução, adaptação e evidências de validade para a medida de Conflito trabalho-família. Avaliação Psicológica, 12(2),203-212. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712013000200011 [ Links ]

Aguiar, C. V. N., & Bastos, A. V. B. (2019). Escala Multidimensional de Conflito Trabalho-Família: Evidências de Validade e Recomendações de uso. In C. S. Hutz, D. R. Bandeira, C. Trentini, & A. C. Vazquez (Orgs.), Avaliação no contexto organizacional e do trabalho (pp. 114-123). Artmed. [ Links ]

Allen, T. D., French, K. A., Dumani, S., & Shockley, K. M. (2020). A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6),539-576. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000442 [ Links ]

Blustein, D. L., & Guarino, P. A. (2020). Work and Unemployment in the Time of COVID-19: The existential experience of loss and fear. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0022167820934229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820934229 [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: Algumas considerações. Paideia, 22(53),423-432. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2012000300014 [ Links ]

Braun, A. C., Machado, W. D. L., De Andrade, A. L., & Oliveira, M. Z. (2019). Why work-family conflict can drive your executives away?. Revista de Psicología, 37(1),251-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.18800/psico.201901.009 [ Links ]

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: Development and validation of a work-family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1),131-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002 [ Links ]

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and Initial Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Work-Family Conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2),249-276. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713 [ Links ]

Clark, M. A., Early, R. J., Baltes, B. B., & Krenn, D. (2019). Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9529-2 [ Links ]

Collins, C. (2019). Who to Blame and How to Solve It: Mothers' Perceptions of Work-Family Conflict across Western Policy Regimes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(3),849-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12643 [ Links ]

Dalege, J., Borsboom, D., van Harreveld, F., & van der Maas, H. L. J. (2017). Network Analysis on Attitudes: A Brief Tutorial. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(5),528-537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617709827 [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2013). Contribuições da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória Multigrupo (AFCMG) na avaliação de invariância de instrumentos psicométricos. Psico-USF, 18(2),211-220. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712013000200005 [ Links ]

De Andrade, A. L., Ferraz, K. R., Oliveira, M. Z. de, & Hatfield, E. (2019). Anticipated work-family conflict in Brazilian university students: Measurement and relationships with attachment and career success. Psychologica, 2,95-113. https://doi.org/ 10.14195/1647-8606_62-2_6 [ Links ]

De Andrade, A. L., Moraes, T. D., Martins-Silva, P. O., & Queiroz, S. S. (2020). Conflito trabalho-família em profissionais do contexto hospitalar: Análise de preditores. Revista de Psicología, 38(2),451-478. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202002.004 [ Links ]

De Andrade, A. L., Oliveira, M. Z. de, & Hatfield, E. (2017). Conflito trabalho-família: Um estudo com brasileiros e norte-americanos. Revista Psicologia, Organizações e Trabalho, 17(2),106-113. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2017.2.12738 [ Links ]

De Andrade, A. L., Oliveira, M. Z. de, Knowles, C. M. M. H., Neto, H. de C. B., & Hatfield, E. (2018). Relational models and work-family conflict: A study with samples from Brazil and the United States of America. Ciências Psicológicas, 12(2),167-176. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1679 [ Links ]

Ferrando, P. J., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2017). Program FACTOR at 10: origins, development and future directions. Psicothema, 29(2),236-240. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.304 [ Links ]

Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D., Ferreira, M. C., & Valentini, F. (2016). Evidências de validade da Escala de Enriquecimento Trabalho-Família em amostras brasileiras. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 18(1),100-112. https://doi.org/10.15348/1980-6906/psicologia.v18n1p100-112 [ Links ]

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1),76-88. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1985.4277352 [ Links ]

Grönlund, A., & Javornik, J. (2014). Great Expectations: Dual-Earner Policies and the Management of Work-Family Conflict: The Examples of Sweden and Slovenia. Families, Relationships and Societies, 3(1),51-65. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674313X13796044783891 [ Links ]

Haslam, D. M., Patrick, P., & Kirby, J. N. (2014). Giving Voice to Working Mothers: A Consumer Informed Study to Program Design for Working Mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8),2463-2473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0049-7 [ Links ]

International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Testes (Second edition). https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf [ Links ]

Islam, T., Ahmad, R., Ahmed, I., & Ahmer, Z. (2019). Police work-family nexus, work engagement and turnover intention: Moderating role of person-job-fit. Policing, 42(5),739-750. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2018-0138 [ Links ]

Kossek, E. E., & Lee, K. (2017). Work-family conflict and work-life conflict. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.52 [ Links ]

Lassance, M. C. P., & Sarriera, J. C. (2009). Carreira e saliência de papéis: Integrando o desenvolvimento pessoal e profissional. Revista Brasileira de Orientação Profissional, 10(2),15-32. [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Seva, U., Timmerman, M. E. & Kiers, H. A. (2011). The hull method for selecting the number of common factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(2),340-364. [ Links ]

Machado, W., Vissoci, J., & Epskamp, S. (2015). Análise de rede aplicada à psicometria e à avaliação psicológica. In C. S. Hutz, D. R. Bandeira & C. M. Trentini (Eds.), Psicometria (pp. 125-146). Artmed. [ Links ]

Matias, M., & Fontaine, A. M. (2014). Managing multiple roles: Development of the Work-Family Conciliation Strategies Scale. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17(17). https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2014.51 [ Links ]

Nauman, S., Zheng, C., & Naseer, S. (2020). Job insecurity and work-family conflict: A moderated mediation model of perceived organizational justice, emotional exhaustion and work withdrawal. International Journal of Conflict Management, 31(5),729-751. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-09-2019-0159 [ Links ]

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4),400-410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400 [ Links ]

Powell, G. N., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2006). Is the opposite of positive negative? Career Development International, 11(7),650-659. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610713508 [ Links ]

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach's alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(MAY),1-8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769 [ Links ]

Powell, G. N., Greenhaus, J. H., Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., Balkin, D. B., & Shanine, K. K. (2018). Family science and the work-family interface: An interview with Gary Powell and Jeffrey Greenhaus. Human Resource Management Review, 28(1),98-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.05.009 [ Links ]

Rehman, A., & Khan, M. I. (2018). Work-Family interface and women school heads: A Pakistan case Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2),1-11. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331112186 [ Links ]

Rocco, P., Bensenor, I. M., Griep, R. H., Barreto, S. M., Moreno, A. B., Alencar, A. P., Lotufo, P. A., & Santos, I. S. (2019). Work-Family Conflict and Ideal Cardiovascular Health Score in the ELSA-Brasil Baseline Assessment. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(20),e012701. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012701 [ Links ]

Sevä, I. J., & Öun, I. (2015). Self-Employment as a Strategy for Dealing with the Competing Demands of Work and Family? The Importance of Family/Lifestyle Motive. Gender, Work & Organization. 22(3),256-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12076 [ Links ]

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach's alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(MAY),1-8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769 [ Links ]

Vilela, N. G. S., &; Lourenço, M. L. (2018). Conflito trabalho-família: Um estudo de casos múltiplos com mulheres trabalhadoras. Pensando familias, 22(2). http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1679-494X2018000200005 [ Links ]

Wayne, S .J., Lemmon, G., Hoobler, J. M., Cheung, G. W., & Wilson, M. S. (2017). The ripple effect: A spillover model of the detrimental impact of work-family conflict on job success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6),876-894. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2174 [ Links ]

Westring, A. F., & Ryan, A. M. (2011). Anticipated work-family conflict: A construct investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2),596-610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.02.004 [ Links ]

Young, M., & Schieman, S. (2017). Scaling Back and Finding Flexibility: Gender Differences in Parents' Strategies to Manage Work-Family Conflict. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(1),99-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12435 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Alexsandro Luiz de Andrade

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia

Av. Fernando Ferrari, n. 514, Goiabeiras

Vitória, ES, Brazil. CEP 29075-910

E-mail: alexsandro.deandrade@yahoo.com

Received: September 10th, 2020

Accepted: June 15th, 2021

Funding: The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq); Espírito Santo Research and Innovation Support Foundation (FAPES).

text in

text in