Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.24 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPSP13547.en

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY AND POPULATION'S HEALTH

Using photographic methods in the mental health field: an integrative review

Uso de métodos fotográficos no contexto da saúde mental: uma revisão integrativa

Uso de métodos fotográficos en el contexto de la salud mental: una revisión integrativa

Gabriela Trombeta ; Lívia Scienza

; Lívia Scienza ; Maria de Jesus D. dos Reis

; Maria de Jesus D. dos Reis

Postgraduate Program in Psychology, Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar)

ABSTRACT

Methods using production of photographs have been explored as alternative instruments of qualitative research and psychological intervention. However, there is still little consensus in their designations and procedures. In this context, this work presents an integrative review aimed at investigating the use of photographic methods in the field of mental health over the last 20 years. The research was conducted on the LILACS, Psycnet, PubMed, SciELO, and Web of Science databases. Forty-nine articles were accepted and 457 rejected. Four methods were identified: Photovoice, PhotoInstrument, Autophotography and Photo elicitation. As potential aspects, the use of photography means exploring and sharing personal experiences, assisting health professionals, and creating empowerment. As challenge aspects, the recent feature of photographic methods used in the field of mental health were highlighted, counting on the prevalence of small and non-generable samples, multiple data analysis methodologies and inappropriate uses of designations regarding the procedures that were performed.

Keywords: photography, psychology, research, visual methods, review

RESUMO

Métodos que utilizam da produção de fotografias têm sido explorados como instrumentos alternativos de pesquisa qualitativa e intervenção psicológica. Entretanto, ainda há pouco consenso em suas denominações e procedimentos. Nesse contexto, a presente revisão integrativa visa investigar o uso de métodos fotográficos no campo da saúde mental, nos últimos 20 anos. A pesquisa foi realizada nas bases de dados LILACS, PsycNET, PubMed, SciELO e Web of Science. Incluíram-se 49 artigos, e excluíram-se 457. Identificaram-se os métodos: fotovoz, instrumento fotográfico, autofotografia e fotoelicitação. Como potencialidades, destacou-se o uso da fotografia como meio para explorar e compartilhar experiências internas, auxiliar profissionais de saúde e gerar empoderamento. Como desafios, prevaleceram aspectos relacionados ao caráter recente do uso de métodos fotográficos no campo da saúde mental, como: predomínio de amostras pequenas e não generalizáveis, múltiplas metodologias de análise de dados e utilizações inadequadas de terminologias em relação aos procedimentos realizados.

Palavras-chave: fotografia, psicologia, pesquisa, métodos visuais, revisão

RESUMEN

Métodos que utilizan la producción de fotos han sido explorados como instrumentos alternativos de investigación cualitativa y intervención psicológica. Sin embargo, aún hay poco consenso en relación a sus denominaciones y procedimientos. Esta revisión integrativa investiga el uso de métodos fotográficos en el campo de la salud mental en los últimos 20 años. La investigación fue realizada en las bases LILACS, PsycNET, PubMed, SciELO y Web of Science. Cuarenta y nueve artículos fueron aceptos y 457 excluidos. Se identificaron los siguientes métodos: fotovoz, instrumento fotográfico, autofotografía y fotoelicitación. Como potencialidad ese destacó el uso de fotografías como un medio para explorar y compartir experiencias internas, ayudar a los profesionales de la salud y generar empoderamiento. En los desafíos prevalecieron la caracterización aún reciente del uso de métodos fotográficos en la salud mental, el predominio de muestras pequeñas y no generalizables, múltiples metodologías de análisis de datos y inadecuado de terminologías.

Palabras clave: fotografía, psicología, investigación, métodos visuales, revisión

Various visual methods are used in qualitative research as an alternative to verbal and written methods. The use of images and objects seems to aid study participants to evoke more in-depth and critical thinking regarding a given subject, facilitate the verbalization of experiences, and promote engagement and empowerment among participants by making them active subjects, essential for the production of knowledge and enrichment of data collected by researchers (Glaw et al., 2017; Padgett et al., 2013; Piat et al., 2017).

Even though this paper refers to the use of photographs only, visual methods include paintings, sculptures, drawings, videos, poems, artifacts, and objects. These materials serve as facilitators or data or simultaneously serve as facilitators and data (Sitvast et al., 2010; Padgett et al., 2013).

In case visual material is used as a facilitator instrument only, it serves to support interviews or focal groups, that is, to facilitate the communication of themes, subjects or specific ideas. For instance, it is possible to show the participants pictures regarding a given subject and ask questions about the subject based on the photos' content. In this situation, the photographs only support researchers and participants to develop a conversation, without any requirement that the study participants should have produced them. In addition to their use as an instrument, photographs may also be considered data in qualitative studies when the participants are asked to take pictures of a given subject and share them with researchers. In this case, photographs play not only a supportive role for conversations, but are also considered research data, as they may contain relevant information regarding the participants' perspectives on the object of study.

Photographs taken by participants are recurrently used in studies from different fields of knowledge, such as anthropology (Collier, 1957), social sciences (Smith et al., 2015; Vélez-Grau, 2018), education (Vilà et al., 2016), occupational therapy (Maniam et al., 2016; Greco et al., 2016), nursing (Clements, 2012), psychiatry (Russinova et al., 2018; Sibeoni et al., 2017), and psychology (Oliffe et al., 2017; Quaglietti, 2018). However, even though this methodology (here, we call it photographic methods) is present in different fields of knowledge, various researchers note its innovative role and benefits, especially in the context of mental health research (Glaw et al., 2017; Erdner et al., 2009). The reason is that this methodology addresses subjects that are difficult to express verbally, such as emotion-laden experiences, and populations whose repertoires are not sufficient to enable them to more easily or directly verbalize and express their experiences (Creighton et al., 2013; Drew et al., 2010; Padgett et al., 2013).

Using photographic methods in this context is efficient to value and capture the participants' emotional experiences with greater detail (Erdner et al., 2009), which is essential to deconstruct stigmas related to mental health and aid professionals and students to understand these populations' needs more deeply. Such understanding is facilitated because photographs approximate researchers and participants (Tittoni, 2009) and enable accessing information that may complement or even differ from information obtained only by questionnaires and traditional interviews (Drew & Guillemin, 2014; Glaw et al., 2017; Padgett et al., 2013). Therefore, this resource is beneficial among populations experiencing mental disorders and difficulties in verbally expressing their thoughts and feelings and/or in situations they deem intimidating.

Even though the potential use of methods that adopt photographs taken by participants is acknowledged by the literature addressing mental health, Glaw et al. (2017) note that these methods are underused in this context. One reason seems to be the various denominations and procedures used to refer to these methods, impeding them to become accessible and comprehensible by researchers and professionals who desire to use them in the mental health field.

Considering these aspects and a lack of literature systematizing the use of photographic methods in mental health, this study's objective was to perform an integrative review to answer the following questions: What photographic methods have been used in the context of mental health? What are the methodologies involved in their applications? How are data produced by these methods analyzed? What are the effects reported in the literature?

Method

The following databases were consulted considering the strings presented in Table 1: LILACS, Psycnet, PubMed, SciELO, and Web of Science. These strings were chosen after the following combination of words were searched in these databases: "Fotografia AND Saúde Mental/Photography AND Mental Health/Fotografia AND Salud Mental". The purpose was to identify which terms are used in the literature to refer to the use of photographs taken by participants in the context of mental health research. Hence, the strings chosen for this review (Table 1) refer to the photographic methods found in this previous search.

The articles were searched and selected from October 2018 to January 2019. The following inclusion criteria were adopted: 1) Articles written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish; 2) Published in peer-reviewed journals; 3) Published between 1999 and 2019; 4) Empirical studies in the mental health field; 5) Photographs taken by the study participants; and 6) Studies including participants with indicators of mental disorders (with a diagnosis and/or receiving clinical treatment and/or using medications for the mental condition). The exclusion criteria were: 1) Articles written in other languages; 2) Published in non-peer-reviewed journals; 3) Published before 1998; 4) Non-empirical studies and/or not related to mental health; 5) The photographs used were not taken by the study participants; and 6) Participants did not present mental disorders. All the papers that appeared more than once, or which met the exclusion criteria, were excluded. The papers included met all the inclusion criteria previously mentioned. Examples of titles of the papers that met the inclusion criteria 4, 5, and 6 are presented in Table 2. The remaining inclusion criteria (1, 2, and 3) were not presented because they focused only on language restrictions, publication date, or lack of peer review.

Two researchers made the initial selection of papers to decrease biases in the process. Each researcher searched for the strings in the databases and downloaded their results in Parsif.al (https://parsif.al). Both read the abstracts and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. When an abstract did not provide sufficient information to apply the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the full texts of the papers were consulted. After this individual work, each researcher created a table, listing the papers included and excluded from the review, providing at least one justification. A third researcher, familiar with the topic under study and very experienced in the conduction of literature reviews, assisted in disagreements. She read both researchers' reports and verified the full texts of the studies to make the final decision. Subsequently, the primary author of this study read and analyzed the data from the accepted papers.

A form was developed in Parsif.al to extract the relevant items, namely: Author, Year of publication, Authors' affiliations, Country of origin, Journal, Study objective, Target population, Photographic method used, Purpose, Population, Instructions provided to the participants, Number and duration of meetings, Number of photos asked, How long the participants had to take the photos, Individual interviews or group debates, Data analysis, Contributions, Limitations, and Additional information.

After reading and completing the forms for each article, qualitative analyses were performed for each of the items above, recording them in tables, grouping repeated items, and organizing them in ascending order. Finally, a critical analysis of data was performed, interpreting the results, and synthesizing the most relevant aspects.

Results

In total, 506 papers were found, 49 of which met the inclusion criteria, while 191 were excluded due to duplication, and 266 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria1 (Kappa = 0.801). As for the studies included, the publications were most prevalent between 2016 and 2018. Figure 1 presents the study selection process flowchart and the distribution of the papers over time.

Photographic Methods

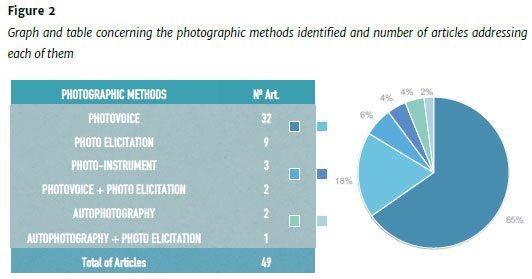

Four ways in which the photos taken by the participants are used in the context of mental health were found: Photovoice, Photo elicitation, PhotoInstrument, and Auto-photography. Some studies also report on a combination of procedures, such as Auto-photography and Photo elicitation (Glaw et al., 2017) or Photovoice and Photo elicitation (Oliffe et al., 2017). Figure 2 presents the number of articles that used each of the methods.

Contradictions were found in the way these methods are described in the selected studies. Thus, the definitions and features of each are described using the bibliographic references of the authors that first developed them.

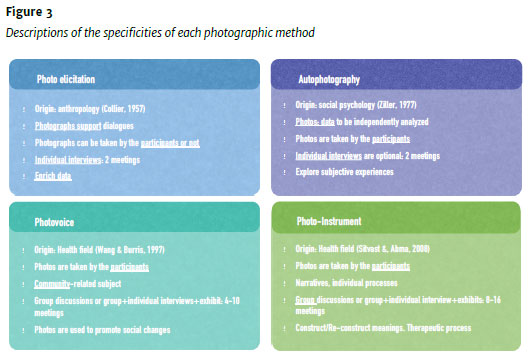

Photo elicitation originated in anthropology (Collier, 1957) and consists of using photographs in an individual interview to evoke thoughts and encourage participants to talk by asking them to look at the photos and answer questions. In this method, photographs are not considered data; instead, they serve as a support material to prompt conversations and enrich data. For this reason, pictures can be taken by participants, by a third party, selected from a personal archive or chosen by the researchers. When a participant takes the photos, the procedure generally occurs at two different points in time, the first to provide guidance and instructions, and the second for the participant to discuss them with the researcher.

As for auto-photography, its first records go back to social psychology research (Ziller, 1990), consisting of asking participants to take photos in response to a question and/or theme. The photos are then handed over to a researcher, who analyzes them to explore the photographer's subjective experiences. In this method, the photos represent data and have to be taken by the participants, although the use of interviews for the participants to provide further details about the photos is optional.

Photovoice, in turn, originated in the health field (Wang & Burris, 1997) and is described as Participatory Action Research (Wang, 1999). In this method, photos are used to identify, represent, and discuss relevant subjects to a specific community. With this objective in mind, researchers or professionals work together with groups composed of community members to identify a theme they consider essential to discuss. After choosing the topic, the community members are asked to take photos that reflect their views. Afterward, the individual responsible for the procedure meets with these individuals and mediates focal groups to discuss the photographs. The primary objective of the evoked dialogues is to promote social changes. As there is an intention to implement an intervention, more extended periods are needed for the Photovoice method, with weekly meetings being held for four to ten weeks. Individual interviews can be added to this method, and a photographic exhibition is usually organized at the end of the procedure to share the photos and discussions that took place with the health workers or the community (Maniam et al., 2016; Paton et al., 2018; Quaglietti, 2018; Teti et al., 2016; Werremeyer et al., 2016).

The PhotoInstrument method is an adaptation of the Photovoice (Sitvast & Abma, 2011). Both methods ask participants to take photos and include group discussions that usually last extended periods and are intended to implement an intervention. The difference is that, in the PhotoInstrument, themes are not related to a community but to individual processes, with the main purpose of constructing and/or reconstructing the meanings of an experience as a therapeutic process. Other denominations related to the PhotoInstrument, mentioned by Sitvast and Abma (2011), are PhotoStories, PhotoGroups, and Hermeneutic Photography.

Common procedures

The four methods share the following procedure: asking participants to take photos to answer a given question or theme, giving them some time to take the photos, and then asking them to bring the photos to a researcher or professional. The photos may be simply delivered to the researcher or professional or, depending on the method used, a discussion may take place. In the case of a discussion, the sessions are recorded and transcribed for qualitative analysis. All these methods include the possibility of combining other methods relevant to the study's objective, such as forms addressing demographic information, Likert scales, validated scales or scales developed by the researchers, field diaries, or narratives, among others.

The descriptions of each method and the synthesis presented in Figure 3 show that the way the discussions are organized and the number of meetings may vary in each method, possibly including individual or group sessions, using semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions. Even though the questions are not standardized, five questions, called the SHOWED method, are reported in 14 of the papers selected. Wang et al. (2004) proposed this method, which consists of the following questions: What do you see? What is really happening? How is it related to our lives? Why does this problem or strength exist? What can we do about it?

There is no consensus regarding the amount of time or the number of photos the participants are allowed to take. These vary according to the authors' research conditions. The studies included here report that the participants had from one to four weeks to take the photos, and the number of photos ranged from 1 to 27. Another possibility is not to determine the number of photos during the first meeting; instead, the participants are asked in the subsequent meeting to choose the photos they consider to be more relevant, or the ones they liked more, or which they would like to discuss. This is a way to allow the participants to make the first selection of data and make the dialogue less monotonous.

Regarding the type of population in which the methods are used, small samples were identified, with studies addressing individuals with severe mental disorders, with two different concomitant diagnoses or intellectual impairment and adolescents under psychiatric care. These specific populations were identified because of this review's inclusion criteria: participants with psychological disorders, either confirmed through reports or the use of psychotropic medications or being committed to mental health facilities. Thus, note that this kind of method is also adopted in studies addressing populations of varied ages and social or health conditions, and the non-identification of other populations is possibly due to the restrictions imposed by this study's design only.

Purposes and effects of using participant-generated pictures in mental health research

Most of the authors of the included studies reported that the main purpose of using photographic methods is to use photographs as a way to share and explore inner experiences and aid professionals to understand subjective individual experiences. Photographs were also used to support interviews, to measure self-reported feelings, to facilitate engagement, recovery, assignment of meanings or re-signification of an experience, and to encourage social changes.

As for the effects observed after the procedures, the authors emphasize that allowing the participants to express themselves with pictures, in addition to the dialogue, empowered them, facilitated the emergence of relevant information for researchers and professionals, and also triggered a critical self-reflection process in the participants. Self-reflection is usually verified in the participants' reports, stating that the photographs allowed them to acquire greater awareness of themselves and their recovery process. Some studies also report that the photos created a bridge between experienced events and verbal expression, enabling them to re-signify experiences, facilitating the participants' engagement.

Data analysis of photographs and interviews

Regarding data analysis, two possibilities in which photographic data were considered and the order in which they were analyzed were identified: 1) interviews were independently analyzed, followed by a combination of photographs and interviews for joint analysis; and 2) the photographs were attached to the transcriptions of the interviews for a joint analysis.

Regarding the theoretical framework used to ground the analyses, various methodologies and approaches were identified, mainly: Thematic Content, according to the model proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006); and Grounded Theory, by Strauss and Corbin (1990) or Charmaz (2006). Other analyses were: hermeneutic analysis, semiotic analysis, iconographic analysis, linear regression analysis of mixed effects, content analysis, and discursive analysis. References were also found to the use of software to analyze data. Eight studies reported Atlas.Ti, four NVivo, and one study reported Stata11.

The procedures frequently mentioned as ensuring the reliability of data were the triangulation of data and independent analyses performed by each researcher, followed by a reconciliation of results. There were also procedures in which the participants took part in the initial analysis of their photos and/or verified the analysis performed by the researchers, expressing their agreement or suggesting corrections.

Discussion

The use of visual methods involving photos taken by the participants seems to be recent in the mental health field, considering that a larger number of the studies were published in the last three years. Their use is even more recent in Brazil, as only five papers by Brazilian authors were found, while only one met the inclusion criteria (Carvalho et al., 2012). A higher prevalence of studies was found in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Netherlands.

The most frequently reported photographic method was Photovoice. When verifying whether the procedures corresponded to the descriptions and names adopted by the main authors of each of the methods (Collier, 1957; Ziller & Smith, 1977; Wang & Buris, 1997; Sitvast & Abma, 2011), however, many of the studies were found to inappropriately name the procedures adopted. For instance, the term Photovoice was used to name procedures that did not include community-related themes, did not include group discussions, or were not intended to promote social changes. This is an important element to highlight, considering that it can cause confusion and lead to inconsistencies in the literature. In addition to rise questions regarding the reliability of the data found in reviews, the incongruence of methods' name adopted according the procedures that were performed rises questions on whether the most used method was indeed Photovoice. Thus, despite Photovoice being the most frequently mentioned by the authors, the most used procedures may correspond to other method, such as Photo elicitation.

Despite confusion regarding the names of the methods, and the fact that only the Photovoice is related to Participatory Action Research, all the photographic methods or other visual methods generally propose a rupture with the traditional researcher-participant relationship, in which researchers are responsible for the study, production, and dissemination of knowledge, while the participants are the study's subjects who only provide data. Asking participants to produce photographs or other visual material regarding a given topic seeks to approximate researchers and the community, putting both as equal contributors to knowledge production (Cabassa et al., 2013) and giving a voice to the participants by changing relationships of power. These relationships can take different forms in a study, whether at the time of establishing its theme and format or when discussing or analyzing the material.

When considering the use of photographs in research, one should take into account some issues related to the study object, for instance: What is the cultural and contextual relevance of images to address a given subject? What is the connection of the participants with the method proposed? What is the relevance of using images and interviews to answer a research question? What are the risks and benefits in this specific context? What is the theoretical and methodological foundation justifying its use?

In this sense, there were many similar references regarding the purposes that led the authors to choose photographic methods in their studies. There seems to be a consensus that photographs are an instrument to share and explore inner experiences and aid professionals in understanding and treating a population's experiences.

Regarding the main effects reported after using photographic methods, the studies frequently reported that: 1) the participants were empowered and they mentioned a feeling of autonomy, valorization, and motivation; 2) the participants were encouraged to critically self-reflect upon their personal lives, promoting the reconstruction of meanings for experiences with a greater awareness of oneself and the recovery process; and 3) the photographs also served as a bridge between experiences and the verbalization of experiences, contributing to the effects described by the participants and to identify information that is relevant for health workers.

Practical examples of these effects are illustrated by empirical studies such as Quaglietti's (2018), the objective of which was to examine the benefits of using photographs as a therapeutic intervention together with other mental health outpatient care actions. The study adopted the Photovoice method and addressed 31 war veterans experiencing post-traumatic stress, depression, or severe mental disorders. Weekly meetings were held for six weeks. The participants were instructed in every meeting to take photos and bring a determined number of photos depicting their recovery history. In the following meetings, the participants were asked to talk about the photos according to a script. The discussions were recorded and later transcribed. At the end of the study, each participant should have produced 25 photos, of which they selected six for a collective exhibit depicting their recovery histories. At the beginning and end of each meeting, they also rated the intervention's effects on a Likert scale. Quaglietti (2018) reports that the photos supported patients in their self-knowledge process, facilitated dialoguing about experiences they considered challenging to share, and gave them a sense of purpose, enabling them to understand how ideas regarding their recovery could be changed as their thoughts and emotions were more deeply explored.

Differently from the consensus achieved regarding the purposes and effects of the photographic methods, data analyses seem to be a controversial aspect, considering the large variety of methods and approaches adopted. This considerable diversity may be explained by the fact that it is challenging to analyze subjective data presented in images along with data collected from the interviews. The very few studies using photos as data to be analyzed independently reveals that this is a real challenge to be overcome.

According to Drew and Guillemin (2014), even though researchers adopting visual methods recognize the expressive and cultural nature involved in the development of images, there is a considerable discussion regarding the processes involved in their analyzes. While some researchers discuss the realistic approach of images as "truths" and promote the essential role of viewers (the public or the researcher) in the interpretation of meanings, others discuss the transience and validity of this interpretation, valuing only the interpretation of the image's creator, which is accessed through interviews and focal groups. There is also a third group seeking to balance these points of view, recognizing the value of both the interpretation of the images' creator and the public in the process of data analysis, as is the case of the interpretative framework analysis (Drew & Guillemin, 2014).

Despite these questions, the selected studies included a group of individuals with very different characteristics in the same population (e.g., severe mental disorders, including individuals with depression with individuals with schizophrenia). Even though the articles describe these populations in terms of demographic information such as age, sex, and mental disorders, the presence or absence of psychological treatment and the use of mental health medications, these data are not analyzed or described separately in the results. This procedure may disregard essential and relevant data of a specific population. For instance, when individuals with severe depression are grouped with those with schizophrenia, photographs and discussions of each of these groups could address very distinct themes. Therefore, the particularities of each of the groups would be disregarded, as they are grouped in a large group of severe mental disorders, and only general results are described.

Another critical issue to be noted is that some ethical precautions related to the use of photographic methods differ from the precautions usually taken in psychological research. Thus, in addition to signing a free and informed consent form, the participants have to authorize the use of their photographs and, whenever they photograph other people, these also need to give their consent for their images to be used. A photo and image release form is usually handed to the participants on the same day the instructions regarding the photos are provided, asking for the form to be returned when the photos will be discussed. In addition to issues related to image rights, one has to consider that the task of photographing, reflecting, and talking about images may elicit feelings in the participants that are difficult to process (Padgett et al., 2013). Thus, it is recommended that participants can access psychological services while taking part in the procedures.

Finally, this study's objective was to identify, map, and present the possibilities to use photographs taken by participants in mental health research. Additionally, we attempted to contribute to the consolidation of terminology that is appropriate to each of the methods addressed here and make these methods more accessible to researchers and professionals in the context of mental health by presenting their characteristics and possible ways to apply them.

This study's limitations include the possibility that not all the names used for the existing photographic methods are included. Some of them may not be included in this review's lines because they were not found in our previous research results, or because there were variations in translations.

Additionally, there is a lack of Brazilian studies addressing the topic; so, results and discussions are restricted to international literature. Therefore, future reviews are needed to address the use of participant-generated photographs in broader contexts such as the health field to verify, for instance, whether these issues are also verified in the Brazilian context. Likewise, the publication of empirical and theoretical papers, using the methods mentioned here, is needed to build a broader and more concise literature regarding these methods in the context of mental health research.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. A. A. S., Ximenes, V. M., & Bosi, M. L. M. (2012). Processos de fortalecimento em um Movimento Comunitário de Saúde Mental no Nordeste do Brasil: Novos espaços para a loucura. Aletheia, (37),162-176. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid =S1413-03942012000100012 [ Links ]

Cabassa, L. J., Parcesepe, A., Nicasio, A., Baxter, E., Tsemberis, S., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2013). Health and wellness photovoice project: Engaging consumers with serious mental illness in health care interventions. Qualitative Health Research, 23(5),618-630. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312470872 [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE. [ Links ]

Clements, K. (2012). Participatory action research and photovoice in a psychiatric nursing/clubhouse collaboration exploring recovery narrative. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(9),785-791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01853.x [ Links ]

Collier, J. (1957). Photography in anthropology: A report on two experiments. American Anthropologist, 59,843-859. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1957.59.5.02a10100 [ Links ]

Creighton, G., Oliffe, J. L., Butterwick, S., & Saewyc, E. (2013). After the death of a friend: Young men's grief and masculine identities. Social Science & Medicine, 84,35-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.022 [ Links ]

Drew, S. E., Duncan, R. E., & Sawyer, S. M. (2010). Visual storytelling: A beneficial but challenging method for health research with young people. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12),1677-1688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310377455 [ Links ]

Drew, S., & Guillemin, M. (2014). From photographs to findings: Visual meaning-making and interpretive engagement in the analysis of participant-generated images. Visual Studies, 29(1),54-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2014.862994 [ Links ]

Erdner, A., Andersson, L., Magnusson, A., & Lutzen, K. (2009). Varying views of life among people with long-term mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 16,54-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01329.x [ Links ]

Glaw, X., Inder, K., Kable, A., & Hazelton, M. (2017). Visual methodologies in qualitative research: Autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 6,1-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917748215 [ Links ]

Greco, V., Lambert, C. H., & Park, M. (2016). Being visible: PhotoVoice as assessment for children in a school-based psychiatric setting. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(3),222-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1234642 [ Links ]

Maniam, Y., Kumaran, P., Lee, Y. P., Koh, J., & Subramaniam, M. (2016). The journey of young people in an early psychosis program involved in participatory photography. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(6),368-375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022615621567 [ Links ]

Oliffe, J. L., Creighton, G., Robertson, S., Broom, A., Jenkins, E. K., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Ferlatte, O. (2017). Injury, Interiority, and Isolation in Men's Suicidality. American Journal of Men's Health, 11(4),888-899. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316679576 [ Links ]

Padgett, D. K., Smith, B. T., Derejko, K. S., Henwood, B. F., & Tiderington, E. (2013). A picture is worth ...? Photo elicitation interviewing with formerly homeless adults. Qualitative health research, 23(11),1435-1444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313507752 [ Links ]

Paton, J., Horsfall, D., & Carrington, A. (2018). Sensitive inquiry in mental health: A tripartite approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1),1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918761422 [ Links ]

Piat, M., Seida, K., Sabetti, J., & Padgett, D. (2017). (Em)placing recovery: Sites of health and wellness for individuals with serious mental illness in supported housing. Health & Place, 47,71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.07.006 [ Links ]

Quaglietti, S. (2018) Using photography to explore recovery themes with veterans. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(2),220-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2018.1425174 [ Links ]

Russinova, Z., Gidugu, V., Bloch, P., Restrepo-Toro, M., & Rogers, E. S. (2018). Empowering individuals with psychiatric disabilities to work: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3),196-207. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000303 [ Links ]

Smith, B. T., Padgett, D. K., Choy-Brown, M., & Henwood, B. F. (2015). Rebuilding lives and identities: The role of place in recovery among persons with complex needs. Health & Place, 33,109-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.002 [ Links ]

Sibeoni, J., Costa-Drolon, E., Poulmarc'h, L., Colin, S., Valentin, M., Pradère, J., & Revah-Levy, A. (2017). Photo-elicitation with adolescents in qualitative research: An example of its use in exploring family interactions in adolescent psychiatry. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 11, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0186-z [ Links ]

Sitvast, J. E., Abma, T. A., & Widdershoven, G. M. A. (2010). Facades of suffering: Clients' photo stories about mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24(5),349-361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2010.02.004 [ Links ]

Sitvast, J. E., & Abma, T. A. (2011) The photo-instrument as a health care intervention. Health Care Anal, 20,177-195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-011-0176-x [ Links ]

Strauss A., & Corbin J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage. [ Links ]

Teti, M., Cheak-Zamora, N., Lolli, B., & Maurer-Batjer, A. (2016). Reframing autism: Young adults with autism share their strengths through photo-stories. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31(6),619-629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.002 [ Links ]

Tittoni, J. (2009). Psicologia e Fotografia: Experiências em intervenções Fotográficas. Editora Dom Quixote. [ Links ]

Vélez-Grau, C. (2018). Using Photovoice to examine adolescents' experiences receiving mental health services in the United States. Health Promotion International, 34(5),912-920. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day043 [ Links ]

Vilà, M., Pallisera, M., & Fullana, J. (2016). Exploring the present and projecting the future: People with severe mental illness speaking for themselves. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(9),1118-1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1201164 [ Links ]

Wang, C. C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of Women's Health, 8(2),185-192. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185 [ Links ]

Wang, C., & Burris, M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior, 24,369-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309 [ Links ]

Wang, C., Morrel-Samuels, S., Hutchison, P. M., Bell, L., & Pestronk, R. M. (2004). Flint Photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. American Journal of Public Health, 94(6),911-913. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.6.911 [ Links ]

Werremeyer, A. B., Aalgaard-Kelly, G., & Skoy, E. (2016). Using Photovoice to explore patients' experiences with mental health medication: A pilot study. Mental Health Clinician, 6(3),142-153. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2016.05.142 [ Links ]

Ziller, R. C., & Smith, D. E. (1977). A phenomenological utilization of photographs. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 7,172-182. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916277X00042 [ Links ]

Ziller, R. (1990). Photographing the self: Methods for observing personal orientations. Sage. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gabriela Trombeta

Via Washington Luis, Km 235

São Carlos, SP, Brazil. CEP 13565-905

E-mail: gabriela_trombeta@hotmail.com

Received: June 25th, 2020

Accepted: May 18th, 2021

This research was funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) - Funding Code 001 - and the Sāo Paulo Research Foundation (Fapesp) - Process 2018/10632-8.

1 The list of included articles is available at https://github.com/gtrombeta/Fotografia-e-psicologia_artigo/blob/master/ANEXO%201%20-%20Refer%C3%AAncias%20bibliogr%C3%A1ficas%20dos%20artigos%20aceitos.pdf

texto em

texto em