Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Natureza humana

versão impressa ISSN 1517-2430

Nat. hum. vol.13 no.2 São Paulo 2011

Artigos

Human Dwellings as Time Expressions: Dialogue Between Heidegger and Dōgen

As habitações do humano como expressões do tempo: diálogo entre Heidegger e Dōgen

José Carlos Michelazzo1

Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo

e-mail: jocmiche@yahoo.com.br

Abstract

This essay is intended to present introductory contributions to the problem of time by putting into dialogue two thinkers: Heidegger and Dōgen. The strategy for both will show a continuum of three modes of human habitation, taken as ways of being human, from three modes of possible interpretation of the time problem. The initial two are presented under the perspective of Heidegger's thought: the first one, the anthropocentric, is the one that is established from a first interpretation of time as a simple duration; the second, the existential, is time as finitude or relative impermanence. The third one, the numinous, under Zen Master Dōgen's perspective of thought, is apprehended from time as radical impermanence. In this continuum of modes of dwelling would be a supposition that there is a deepening in the comprehension of the being of man that would imply, in turn, with a correspondent deepening in the way of interpreting the problem of time, in other words, of apprehending it more originally.

Keywords: ontology, dwelling, time, permanence, finitude, impermanence.

Resumo

A exposição pretende apresentar contribuições introdutórias para o problema do tempo ao colocar em diálogo dois pensadores: Heidegger e Dōgen. A estratégia para tanto será mostrar um continuum de três modos de habitação do humano, tomadas como maneiras de ser do homem, oriundas de três possíveis horizontes de interpretação do problema do tempo. Os dois iniciais apresentam-se sob a perspectiva de pensamento de Heidegger: o primeiro modo, o antropocêntrico, é o que se estabelece a partir de uma primeira interpretação do tempo enquanto permanência, como simples duração; o segundo, o existencial, do tempo como finitude ou impermanência relativa. O terceiro, o numinoso, sob a perspectiva de pensamento do Mestre Zen Dōgen, é apreendido a partir do tempo enquanto impermanência absoluta. Nesse continuum de modos de habitação estaria contida uma suposição de que existe um aprofundamento na compreensão do ser do homem que implicaria, por sua vez, em um correspondente aprofundamento no modo de interpretar o problema do tempo, ou seja, de apreendê-lo mais originariamente.Palavras-chave: ontologia, habitação, tempo, permanencia, finitude, impermanencia

INTRODUCTION

The problem of time has always been an object of concern among thinkers, and this concern is always more lively when it gets further from objective time and closer to the existence of things in general, becoming even more mysterious when connected to the human existence. This happens because time relates differently with the various types of existence; for instance, the time of the rock, the time of the plant, the time of the animal and the time of man. Among all, human existence is the one which relates more with time. This work will deal with two great thinkers that are also interested in the problem of time related with human existence: the first one, Heidegger, the German thinker who belonged to our contemporary time; and the second one, Dōgen, a Zen master who lived in Japan in the first half of the thirteenth century. In this case, it is mandatory to first ponder the question: What makes these two thinkers so interesting, when their lives are marked with two extreme differences: both in time (separated by seven centuries) and in culture (Western and Eastern)?

Maybe the answer is in the fact that both speak, in their own ways, about time in a singular way, not in the sense of deepening our knowledge about time, but in highlighting the human existence, or more precisely, in exposing us to ourselves. Concerning Heidegger, this singular thinking made him the first thinker to connect the problem of time with the question of finitude of human existence. For Dōgen, on the other hand, singular thinking allowed him to take the problem of impermanence to the limits of paradox and freedom.

And it is because they talk about time – each one under their own perspectives: finitude for Heidegger and impermanence for Dōgen – in connection with human nature that both thinkers, marked by such a distance, are so close. They are close when they share the inseparability of being and time; they are close when they dissipate from all illusion an ontological safety similar to the immortality of a soul or eternal redemption. However, there are keen differences, although essential, that have urged a great interest in research, including my own. The strategy used in our work to talk about the question of time in both thinkers will be to show through a continuum of three modes the human existence, three modes of the human dwelling, through which man could understand his own being, his own humanity, as a result of three possible horizons of interpretation the problem of time. The first dwelling, the anthropocentric, is the one that is established from a first interpretation of time as permanence, as simple duration. The second one, the existential, is under the interpretation of time as finitude or relative impermanence. The third one, the numinous, is under the horizon of time while radical impermanence2. Therefore, in this continuum would be a supposition that there is a deepening in these modes of dwelling in the sense of a more fundamental comprehension of the being of man that would lead to the development of his ability of being to the extreme of its possibilities. Such deepening would imply, in turn, in a correspondent deepening in the way of interpreting the problem of time, in other words, of apprehending it more originally.

Therefore, the dialogue between the two thinkers would be in debate between the three modes of existence connected to three horizons of interpretation of time: the first two Heideggerians and the last Dōgenian; the latter receiving a larger window of exposure since it is less known and more enigmatic. Needless to say that all affirmations and suggestions presented here must be interpreted as primary exercises that intend to contribute to the difficult and, at the same time, challenging encounter between Heidegger and Dōgen, through which we could take the differences of one to deepen in the comprehension of the other and, thus, implement the East-West dialogue. With this brief introduction, we carry on to the succinct exposure of the three modes of human dwellings that arise from three perspectives of interpretation to the problem of time.

1 – ANTHROPOCENTRIC DWELLING:

The human as a search of permanence – the time as a duration experience (Dauer)

Our intention, in this phase, is to present the first mode of human dwelling which is characterized by two main features of its way of thinking and existing: duality and anthropocentrality.

The first is expressed in the irreconcilable division between identity (self) and alterity (the world). It is, therefore, the first mode of understanding ourselves which Heidegger called ‘improper mode' (uneigentlich) as a crystallized being in the figure of one separated from the world. The world, in turn, is always an external ambit to man that must be dominated and, as such, taken as ‘non-self'. We love our being and everything that threatens its existence and continuity; and as a distinct being, it is flagged as an outside danger, from the ‘non-self' of the world. This mode of understanding leads to the discovery that both sides of the real follow different principles (i.e. physical forces), and the interests of the self are not the same as those that rule the world, leading to the world being identified as an obstacle to the existence of the self. Even our own body, as it follows the same principle of living things in the world, is a source of constant disagreement and that, in death, carries the main source of threatening to self. Hence, this man who is "…compelled by the necessity of being absolutely like a separate being, is incapable to accept his existence as it is." (Benoit, 1997, p. 226) Consequently, there is an endless fight between self and the world. This fight is characterized by a long-lasting effort to affirm this self against the world, whose products (presented in the form of material goods, prestige, and fame) are interpreted as icons of recognition of the victory of the self against the world and as a guarantee of the continuity of its separate existence.

The second main feature is a parallel or consequent experience to the duality: it is the anthropocentrality. All this effort and fight against the ‘non-self' and the world ends up emerging in man, both the gradual consolidation of a separate self and a complementary experience of feeling located in a place more and more centralized in the sum of reality. Although he "knows" that he is not the center of the universe, "his imagination avoids him feeling this, recreating in his mind a centralized universe in himself." (Benoit, 1997, pp. 226-227). There would be here, therefore, in its most wide sense, the essence of Humanism which Heidegger understands as the base of sustenance of the metaphysic thought, which he "[…] appoints, so, the process – connected to the beginning, to the development and the end of the metaphysic – through which the man, in perspectives more and more different, but always conscious, puts himself in the center of the being" (Heidegger, 1968, pp. 160-161). Such centrality would express, consequently, the effort of man in showing his supremacy over the world and the victory of his separate self, looking for his own assurance, in other words, with the objective of "[…] getting to the certainty of his destination and putting himself safe from his ‘life'" (Heidegger, 1968, pp. 160-161).

Such duality and anthropocentrality features, which belong to the initial and anthropocentric feature of man dwelling in his humanity, would emerge, in turn, from a mode too early to interpret the problem of time, in other words, of the time understood in an objectified way, once he is taken as a being outside the man and independent of the happenings. This objectified time would be the foundation upon which to support the struggle of man to assure and control his destiny with a projection of human needs to search long and ‘install' the existence in a permanent way. This process of taking the objectified time has its beginning with the solidification of experiences of man related to phenomena and things of his daily world, taken as objects interpreted as outsiders of self, motivating in man the tendency to also take himself or his own existence as something objectified, as one thing among others. It is not saying that there isn't a perception of time action, present in the aging of objects around him or in the change of seasons. However, maybe these changes were slow or almost imperceptible, and they create in man the sensation that such happenings, including his own existence, are more outside than inside the time flow, which makes them apprehended in the mere presentness, in other words, a mere course of isolated time points, a simple passing by of the serial, uninterrupted and irreversible sequence of "nows". Joan Stambaugh – commentator and translator of Heidegger and scholar on Dōgen's thought – points out three aspects of this anthropocentric time: this time can be either an ecstatic recipient that "carries" the happenings or can be something that flows permanently from the future to past, or even it can be the time of an individual life that starts with the birth and runs relentlessly to death. (Stambaugh, 1990, p. 25)

However, with the Greek foundation of metaphysical thought, an event of extreme value related to the problem of time overlaps two fundamental features, as seen above, consolidating them, which, according to Heidegger, represents the fundamental cornerstone of the objectifying feature of Western thought (philosophy and sciences). From this point, the events of the real become represented in the horizon of timelessness, outside of daily existence, common and sensitive. For this, a logical-discursive language is created to be the foundation of theoretical constructs of the anthropological doctrine of reason and the supra-sensitive moral with the intention of detaining such happenings in their permanence by means of notions, concepts, theories, systems, taking them as mere substantialities.

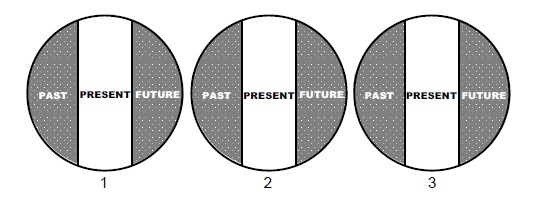

To illustrate, we present this dimension of constancy and timelessness of time, this mode of existence and anthropocentric thinking, though the next drawing:

Here, we try to represent the feature of permanence of time as Heidegger interprets it and, although its three-dimensional feature (present, past and future) is responsible for giving the aspect of the simple going on, the present mode (transparent area) becomes predominant in relation to the other two, as an expression of time retention, in a kind of motionless present (nunc stans) – both in the daily existence and in the metaphysical concepts – that runs constantly in a linear and unidirectional sequence of "nows": present 1, present 2, present 3. The other two modes, the past and the future (shady areas), become, on the other hand, retracted and always taken from the present: the past as a great deposit of happenings that are gone and whose mark is forgetfulness; the future, projected from the present, is either seen charged of fearful or venturous expectations to the common thought or predictable or controllable to the metaphysical thought.

This way, sedimented by a ontological and timeless statute, the humanist doctrine of metaphysics will start what Heidegger calls History of forgetfulness of being, whose phenomena – like nihilism, the modern technique, the massification of man, spiritual vacuum, among others – could be interpreted as outside expressions of dualism, anthropocentrism and objectified interpretation that being and time would represent, in the last instance, the first human experience of being man. Following, we will present a brief exposure of the second mode of human dwelling that will initiate the way called regression to the being, made possible, in turn, by a change in the interpretation of the problem of being and time. This beginning is represented by the thought that Heidegger wants to initiate.

2 – EXISTENCE DWELLING:

The human as a partial acceptance of impermanence – time as finitude (Endlichkeit)

One of the central aspects of Heidegger's thought is the promotion of the anthropological feature deconstruction of Western thought, which he calls metaphysic, for taking the categories of being as an entity simply given (Vorhandenheit) and of time as a mere constant presence, simple presentness (Gegenwärtigkeit). His purpose with the deconstruction is to show the anthropologic mode of man to understand his humanity, though legitimate and possible, it is an illusion, since its existence is not under the feature of time objectified, but under its finitude, more originally and above which he presents a new mode of thinking, the existential, based on a fundamental ontology. So long as he interprets more originally the problem of time in its finite feature, the philosopher rescues from forgetfulness – either from Dasein (first Heidegger), or from History destiny (second Heidegger) – a fundamental dimension of being, its contingent and apophatic feature, never before considered by the Western philosophical tradition. The notion of finitude in Heidegger is, therefore, his attempt to interpret time in a more original way, while connected to the concrete existence of man, for human time is different for a rock, a tree or an animal; they exist in time. Only man ek-siste, which means that existence "leaps" outside, in the sense that it is neither under the control of his representation, nor it belongs to him in any way.

In his lectures in 1927, called "The Basic Problems of Phenomenology", Heidegger says that this leap from existence is determined by the ekstatic feature of time, for "Time, as future, past and present, in itself, is rapturous (entrückt)." (Heidegger, 1975, p. 377) Therefore, "temporality, while a unity of future, past and present…is originated outside itself – the ekstatikón" (Heidegger, 1975, p. 377). It is this "outside itself" of existence, confirmed by the ekstatic feature of time, that allows man to transcend, i.e., being conscious of the world, death, opportunities that are gone or are to come that constrain their ability to perform as a human being. Hence, unlike the plant, man exists as time. Although the three ekstases of time – past, present and future – are gathered in an original unity, according to the philosopher, every "…ekstase belongs to a specific opening that is given as outside itself." (Heidegger, 1975, p. 378) In other words, there is unity of the three ekstases, but with the primacy of the specific opening of one of them over the other two.

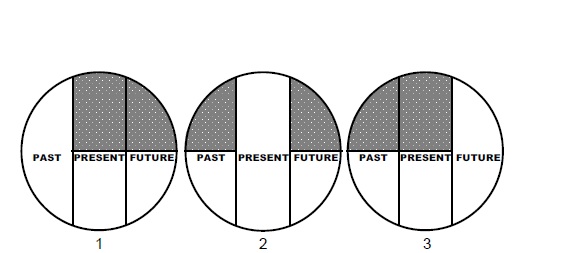

As we did in the anthropological phase, here we try to present the Heideggerian interpretation of finite time with the following drawing:

Here we try to show the predominant ekstatic feature of one of the temporal modes, expressed in the larger transparent area in the circle, in unity with the other two, represented, in turn, by the areas less transparent, as follows: (1) predominance of the past, (2) predominance of the present, or (3) predominance of the future. However, insofar as "to be outside itself" is predominantly opened to only one of the three determining modes of time – at one with the other two, namely, one mode must always take precedence over the others – we understand that the ekstatic feature of finite time is always a "partial" mode of impermanence3.

With this perspective of understanding time from our own existence, says Nishitani – Japanese thinker from the Kyoto School and Heidegger student between 1936-39 – "a ratio completely different in character from the ratio of logic comes to light" (Nishitani, 1982, p. 171) The different feature of this ratio consists, therefore, in the fact that man becomes conscious that, on the one hand, he can only interpret time as something that determines his existence and, on the other hand, can only understand his existence in a temporal way. This awareness of the interdependence between time and existence means that, according to Nishitani, "[...] a dimension of transcendence (...) breaks through the standpoint of discursive understanding and speculative reason to the depth of his own existence" (Nishitani, 1982, p. 171) and reminds us, in turn, of the problem of Nothing and Death as maximum expressions of the finite feature of our lives. This is the reason why Heidegger understands that man is always guided to the future, for this is a kind of "magnetic pole" of existence, once this is born from the future, is projected to the past and then to the present. But the precedence of the future is also related with the proximity of death that, with its constant threat, unveils the authentic Dasein, (i.e. opens to man the conscience of his possibilities more particular to the ability of being). Thus, if man is not in tune with the constant threatening of his death, he is not capable of readapting from the significant aspects of his past, nor can he apprehend a present less diverted and wandering from his daily existence.

Therefore, what feeds Heidegger's path – in both ways of Seinsfrage, under a horizon of finite time, in which their determination and persistence in rigorous exercise of finitude and nihilation of all objectifying metaphysic presupposition – is nothing less than "…the attempting of thinking ‘the being as a being' in relation to tradition, (and, therefore, it) must be taken to the extreme, for and because of that one must not, as a ‘being', let himself be determined." (Heidegger, 1971, p. 390) Take to the extreme this attempt of thinking the "being as a being" (Sein als Sein) – and not as a being, as has always been done in metaphysical tradition –, is to undertake the thought that calculates (Denken als Rechnen) metaphysical humanism to its conclusion, taking the being in its totality to waste and extreme exhaustion, to the edge of the abyss. A chasm, however, must be overcome, for the thanking thought (Denken als Danken) is on the other side and, for Heidegger (unfortunately), "there is no bridge leads to thinking of science, the only possible way is leaping. The place where the leap takes us is not only the other side of the abyss, but also a region totally diversified." (Heidegger, 1958, p. 157)

It is, therefore, to this completely diversified region – to where there is no other way but to leap –, that the Heideggerian thought is oriented while locus of its return project to a mode of thinking the being more originally. Leaving behind all those supra-sensitive concepts that maintained the thought through tradition – First Cause, Absolute Principle, Transcendent Substance, Summum Ens, Ens Realissimum, Subject, Spirit, Will, Person – what appears in this metaphysical emptiness is already a mode of thinking which stays nearby the numinous thinking. With this, Heidegger joins in the effort to override the mode of simply thinking human, presented both in the dualism and anthropocentrism features of metaphysical humanism, thus giving a start to a movement of returning to the thought to a mode directed to a dimension more retracted from reality that we could call trans-anthropocentric because it dwells nearby the sacred (Heilige).

For the philosopher, therefore, the holy – apprehended in the meditative poetry of Hölderlin thinking –, it is that initial totality of the real that unites within itself (harmlessly) everything. By its feature of primordiality, it is always the former, "…for the initial remains in itself intact and safe." (Heidegger, 1981, p. 63)4 This sacred totality "[...] gives, for its omnipresence, to the saved every cent of its security of permanence (Verweilung)." (Heidegger, 1981, p. 63) However, ‘security' here must be understood in an original way, prior to any religious interpretation. In this sense, being secure means agreeing with what was established, since the beginning, to each one of the entities of reality (i.e. its place and destiny). Being secure, therefore, is (One) to experience the belonging and integrating to this original source–while initial and intact One–and together with it feel healed and regenerated because it has found its housing, for "the source is the developing of One in the inexhaustibility of its unit. The One like this is the Simple, (Heidegger, 1981, p. 133) as "…the One that unites originally. This One can only appear when he is a unifier, meeting towards its unity." (Heidegger, 1981, p. 135)

With this One intact and holy that carries no more from the Neoplatonic One – for no longer being a monad, substance or first cause, but that One which unites its power of reuniting, taking the real in its original and totality – Heidegger goes a step further in his approaching to the numinous thought, expressed by the tradition of Western and Eastern mysticism. Therefore, all Heidegger's relations with the mystical thought are not clear, but always ambiguous5. This ambiguity relies, in our understanding, on the fact that the philosopher wants to preserve directed thought for two efforts: first, obtain distance from the objectifying feature of metaphysics and; second, locate himself inside the limits of thinking, but driven by an intense debate with the unforeseen Western philosophical tradition. Therefore, to take a distance from the metaphysical thought is, at the same time, to be opened to influences of traditions rarely customary to metaphysics, such as the artistic (painters and poets like Hölderlin), but also the religious, especially the ones related to the mystical tradition, both Western and Eastern6. Such religious influences "de-objectifies" the experience of thinking, and Heidegger finds both in his own theological studies, as a great expert of medieval scholastics and intrigued by the negative theology (especially Meister Eckhart), more present in the first phase of this thinking path and the Eastern, by his interest in Tao and Zen Buddhism, coming from uncountable contacts with Chinese and Japanese students and counterparts, most significant in the second phase7.

Although those influences, what is seen, is that between these two modes of thinking (the existential and the numinous) according to our understanding – no matter how close they can be in some cases –, there is no straight path, for another abyss separates them. Here, Heidegger's previous words seem to be true, when he referred to the "non-path" between science and thought and the leap between them would be the only accessible way. However, this second leap is now between the being's thought, as Heidegger realizes the task of the thinker and the poet, and the numinous non-thinking, as it is realized in the mystic experience or the awakening Buddha8. Actually, Heidegger himself admits this possibility when splitting an even more retracted horizon of being – a third topos farther than those two thematized by him, the thought and the poetry – in which human existence would share with the divine and with the god of gods, as he expresses in the famous sequences of several openings of the being in his Letter on Humanism, written in 1946

Only as of the truth of the Being (Sein) one is able to think the essence of the Holly (Heilige). Only as of the essence of the Holly one can think the essence of Deity (Gottheit). Only in the light of the Deity's essence one can think and say what the word "God" (Gott) must nominate. (Heidegger, 1976, p. 351)

Heidegger's use of Deity is an explicit reference to Eckhart and his audacious notion of the divine double nature. Gott is the Christian God, Trinitarian, Father, and Creator, who relates with the creatures and receives names according to the historical experiences of these relations. Gottheit, born in the sources of Plotino and Dionysius the Aeropagite's neoplatonism, is the dimension of the divine that remains hidden behind the names, images and representations assigned to him; it is the One of absolute, the bottom without any bottom, the place without any place, where the divine comes from. With this dual conception of the divine, Eckhart allows himself to go farther beyond the religious-Christian God the Creator, particularly to his preacher's task, taking advantage of a more straight, intimate and personal relation, as desired by any mystic. However, Heidegger only points to the possibility of this more retracted dimension of being, but remains in silence, making us understand that it belongs to another model human figure, besides the thinker and the poet.

Therefore it is here, the context, appointed by Heidegger himself, from where it emerged two of our hypothesis: the first, which refers to the leap between the scope of thought into the numinous realm, because there is a change in the interpretation of the finitude and impermanence problem and; the second, the mystic or the awakened man as a model human figure that would occupy this trans-anthropocentric dimension of man: either in his relation with the divine, in his being-with-god-or-gods, as interpreted by the Western perspective; or in his relation with the empty (śūnyatā), as understood by the Eastern perspective.

Next, we will deal with more details the exposition of this more retracted scope of being that opens to man the perspective for what we are calling the third mode of human dwelling that arises, in turn, from a third interpretation of the time problem, carried on by the numinous thought.

3 – NUMINOUS DWELLING:

The Human as Full Refuge of Radical Impermanence – Time as Emptiness (śūnyatā)

This mode of human dwelling will be destined the task of completing the overcoming of anthropocentrism. Such accomplishment becomes possible but its interpretation of the problem of time being based on the feature of absolute impermanence of time, a kind of radicalization of the finite Heideggerian time interpretation. These two steps, the existential and the numinous, would be taking the nominated path, also in the Heideggerian language, the "return to be".

However, before we enter into the central notions of Zen Master Dōgen, it is necessary to point out an important issue. It is the difficult to talk about the extreme religious experience that belongs to Zen Buddhism, since it is, as all mystic experiences, in its essence, incommunicable. In this sense, it would apply to the thought only the exegesis from texts of reference to this experience and, later, possible comments and developments. Stambaugh says that the comprehension of these texts becomes to us, Western beings, an exercise of extreme patience. She comments that, unfortunately, our Western philosophical knowledge – as we find ourselves under some theocentric or anthropocentric record (or even in the perspective of subjectivity that includes polar notions established by metaphysical tradition such as relative-absolute, immanent-transcendent, identity-difference, or finite-infinite) – blocks the path of the guidewords, these texts seeking to convey the essence of this experience in another record, the cosmocentric.

Zen is aware of this difficulty and that it not only exists for Westerners, but for followers. To face this difficulty, rather than using the negative path (the popular path used by Western theology, questioning – what? from where? for what reason? – Zen presents enigmatic questions made by Zen Master to his disciples (both in stories and specially in kōans of Zen) in an attempt to refer to or communicate something "unknowable, unnameable, unobjectifiable, unobtainable, and therefore limitless and infinite" (Stambaugh, 1990, p. 12) The main point of such questions is that they diffuse, open, and amaze, without affirming anything different in us (Westerners); that when we make a statement, it is always in the sense of affirming something. This is the reason why, even knowing the ineffable feature of extreme religious experience, it must be studied and communicated, for this refuse is part of the full experience that is always retracted in mystery. The emphasis, however, must not itself fall in communication itself, but in the response, which has the potential to awaken the listener to see what is meant for him – and only for him, in that moment – becomes manifest. (Stambaugh, 1990, p. 13)

What makes possible the accomplishment of this second leap between the existential dwelling mode and the numinous thought is a limit break. It is about the complete dissolution of those elementary elements of human thought belonging to our anthropocentric identity, ruled by an empirical self (duality) and, at the same time, central in relation to real in its completeness (anthropocentricity). Every thought of the numinous, by several modes and paths, speaks about this effort to dissolve all forms of crystallization, especially of a personal self, to understand them as illusory–being in the Western tradition where creatures separate from God are merely nothing (Eckhart); being in the Eastern tradition where every phenomena is transitory and empty (Dōgen)9.

Although Heidegger transposed a great number of metaphysical dualisms – bound by tradition in its irreducible split type (being and not-being, subject and object, being and time, etc.) –, insofar as he takes his possibilities in a belonging-together (Zusammengehörigkeit), in a way that just one is affirmed in the condition of pertaining to the other, even so there would be some identity left between the poles that remain in a self, as a condition of sustaining with the opposite pole the relation of reciprocal belonging. And it is for this ‘rest' of subsistent identity that the Japanese thinkers from Kyoto School (Abe, 1992 and Nishitani, 1982) understand that Heidegger would still preserve a trace of duality in a way that the apophatic and nihilating features of his thought would not be complete and full, but relative and partial.

To make the leap over the second abyss towards the third mode of human dwelling, it is necessary that the thought reaches the level of śūnyatā, the Sanskrit guide-term to Zen Buddhism by interpreting nothingness or absolute emptiness. The Japanese thinkers found a Western parallel more in Meister Eckhart than in Heidegger, once that for the Rhenish mystic it is no longer a relation, neither the belonging-together kind between man and God in the Heideggerian way between Dasein and Sein. We must go further than co-ownership, where absolute emptiness prevails on both ends of the relation to be interdependent one and the same identity, making the ground of the soul (Grund der Seele) and the ground of God (Grund des Gottes) constitute in the same happening. This single event in Zen Buddhism occurs when the conscience of man reaches the emancipation (todatsu) – that is, it becomes aware because it is free of the dualistic mind – and śūnyatā becomes the same. This happening, in both cases, is the absolute nothingness or emptiness.

To accomplish the transposition of the second abyss, just as Heidegger showed us in the last transposition, between the anthropocentric (science) and existential (thought) dwelling modes, it is necessary to form a new interpretation of the time problem. To have a complete undertaking of duality and anthropocentricity – in a way that the polarities of man and world and being and time, can be in a relation that puts them beyond a mutual pertaining to merge in complete interpenetration –, it is necessary that time is experienced in its radical impermanence. This new interpretation of time for Zen Buddhism appears when we undertake every dualism, and this is possible when we are capable of experiencing the duality poles as identical. For Dōgen, this is only possible for those who have been through the phases of The Way of the Buddha mentioned by him in his Genjokōan:

To learn the Buddha Way is to learn one's own self. To learn one's self is to forget one's self. To forget one's self is to be confirmed by all dharmas. To be confirmed by all dharmas is to effect the casting off one's own body and mind and the bodies and minds of others as well. All traces of enlightenment [then] disappear, and this traceless enlightenment is continued on and on endlessly (Dōgen, 1972, pp. 134-35).

In these five sentences, the second, "to forget the self", is the experience—the breaking of The Way of the Buddha that designates here, for us, the leap over the second abyss, through which the portal to the numinous mode of dwelling is opened. With the tearing down of the self separate from the world, the being in its totality is the one who maintains man as he is confirmed by all the dharmas. This man also loses his mind and body separate from the world, and all traces of duality and centrality of man are left behind for all other bodies and minds of the world and are released from the anthropocentric look which saw them as separate entities. Nor even remains to this man any trace of enlightenment. All of these experiences happen, however, because the horizon of time also suffered a changing; it is then comprehended as radical impermanence. For Dōgen, therefore, those who were run through this experience of time, were emancipated of duality and, as of then, are capable of experiencing the polarities of reality in its complete indistinguishing, in its total identity. Those who have reached this phase of The Way found his true nature, his original totality: the Buddha Nature (Busshō).

It is necessary to observe the fact that in our dualistic mind, when we say identity, even if we qualify it as ‘original', places itself readily against the difference. This is the effort here demanded by Dōgen; for him, the identity includes the difference or even includes duality. Both poles identify themselves in the sense of a complete interpenetration. Maybe we could explain better by using the term ‘non-duality' (i.e. the poles of real do not disappear, at least when they are separate from each other). It is just under this perspective of a complete non-duality that Zen can talk about an identity etween birth and death (i.e. in the fact that we live and die at the same time, at every moment). In this sense, when I say "I am living," it is the same thing if I said "I am dying." For Dōgen, those expressions, even if they may pretentiously mean the opposite, identify with themselves, for they are simply two different ways of referring to the same non-dual reality. The same happens with being and time, whose non-duality is expressed in Japanese by two ideograms ‘U-ji', translated as ‘being-time'. In the first lines of his Shōbōgenzō Uji, the philosophy of being-time, Dōgen utters: ‘The time being' means time, just as it is, is being, and being is all time". (Dōgen, 1979, p. 116)10

Nevertheless, it is necessary to observe the notion of impermanent time so that it is not apprehended dualistically (i.e. totally separate from permanence). Dōgen in his Busshō (Buddha Nature) quotes the comment of Hui-neng (Enō for the Japanese), sixth patriarch of Zen, made to his disciple Hsing-ch'ang to refer to the problem of non-duality of the time problem. He says:

[…] if the Buddha-nature were permanent, what would be the need on top of that to preach about all dharmas good and bad? Even in the elapse of an entire Kalpa there would not be a single person who would ever raise the mind in quest of enlightenment. Therefore I preach impermanence, and just that is the way of true permanence preached by Buddha. On the other hand, if all dharmas were impermanent, then each and every thing would merely have selfhood and would take part in birth and death, and there would be areas to which true permanency did not reach. Therefore I preach permanence, and it is just the same as the meaning of true impermanence preached by the Buddha. […] By mistaking the perfect and subtle words the Buddha spoke just prior to his demise as indicating nihilistic impermanence or lifeless permanence, even though you read the Nirvana Sutra a thousand times over, what benefit could you get from it? (Dōgen, 1976, p. 104)11.

What Dōgen wants to highlight through the words of Hui-neng is that neither permanence, nor impermanence can have a true comprehension if they are viewed in isolation, both taken while excluding each other. If they are interpreted this way, permanence is nothing more than mere death for a duration of time, lifeless, a mere eternalism and, impermanence, an endless flow of time, pure negation of any stability. These described extremities for permanence and impermanence must be avoided; they will never be shown in the form of time experience, for they are nothing more than a mere representation of intellectual construction. Therefore, it is neither about a mere permanence in the mode of anthropocentric dwelling, a mere permanent present; nor a simple impermanence in the finite mode of existential dwelling, once both modes, permanence and impermanence, are fundamental aspects of time. However, such modes can only be truly comprehended when interpreted in their complete interpenetration, beyond their opposition (i.e. by teaching impermanence, one gathers the true permanence; and by teaching permanence, one gathers the true impermanence).

This complete interpenetration between the modes of permanence and impermanence signalize a deep ambiguity in Dōgen's interpretation of time and creates for us, Westerners, an almost impossibility of understanding him. Let us once again draw close to these two modes of time, concerning the Zen Master. The mode of impermanence – continuous time that flows, passable (kyoryaku) – we comprehend. This is true, but only in part because time, in Dōgen's explanation, is not mere impermanence. It is only impermanence when it fuses with the other perspective: the intermittent time, which does not flow, non-passable of here-and-now (nikon). This, in a certain way, is also known for us, the illusory time of the pure present seen earlier. This is true, but also in part because it is not a mere ecstatic permanence, but a present while fused with continuous time. This non-opposition between continuous and discontinuous time is, for Dōgen, the full, absolute present; the fundamental time experienced by man emancipated and free from all duality.

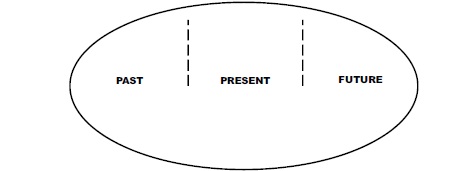

Here, as we did before, we are going to present our interpretation of time in the numinous dwelling, as apprehended by Zen Master (i.e. as absolute present, expressed by the non-duality between permanence, discontinuous, and impermanence, continuous). Unlike the representation of finite-existential time – in which the ekstatic feature is always partial, because the being-out-the-self is open predominantly in only one of the three determining modes of time in connection with the other two – the time modes (past, present and future), i.e. neither of them has a precedence over the other two, but the three, together, form a total opening. This way, the simultaneous predominance of the three time modes is represented, in the drawing below, by the total transparency of it:

This way, the time experience, presented in the enlightenment experience, although it may be a paradox and incomprehensible, apprehends the happenings of the real not only in impermanent time as a simple continuity of the future to the past, but neither in permanent time as a simple discontinuity of a constant present. If we could name this experience of total temporality, we would call it an original "futural-past-presence", in an attempt to say that this absolute (total transparency of the ellipse) has two contradictory aspects: it constantly fuses the future and the past into the present (discontinuous time) and, at the same time, it distinguishes them as singular modes of time (continuous time). Dōgen knows of the non-awakened man's extreme difficulty in understanding this dual aspect of time, having access to only one of them (i.e. to the common time that passes in the modes of present, past and future). He exhorts it to not be stuck only in this aspect, as he does in Uji (Being-time):

You should not come to understand that time is only flying past. You should not only learn that flying past is the property inherent in time. If time were to give itself to merely flying past, it would have to have gaps. You fail to experience the passage of being-time and hear the utterance of its truth, because you are learning only that time is something the goes past (Dōgen, 1979, p. 120).

What Dōgen is trying to communicate to us is that the time more familiar to us, the continuous, is the passing time – is the sequence of nows of the anthropocentric dwelling, is the ekstatic and finite time of the existential dwelling –, it is not so central as we normally suppose and it is just for this that we are prevented of understanding more fully what time is. To explain this, Dōgen gives an example. When the non-awakened man climbs a mountain and crosses a river, both of these happenings are put straight in time; there are two experiences: climb the mountain and cross the river, i.e. "to him, the mountain and river and I are as far distant as heaven from earth." (Dōgen, 1979, p. 119) What common man lacks is integrating this impermanent, continuous time with the impermanent, discontinuous time. Because of this, Dōgen continues,

But the true way of things is not found in this one direction alone. At the time the mountain was being climbed and the river being crossed, I was there [in time]. The time has to be in me. Inasmuch as I am there, it cannot be that time passes away. (Dōgen, 1979, p. 119)

Maybe we could point out to a single difference between Heidegger and Dōgen, concerning the time problem. However, the difficulties of understanding and lack of appropriate words to approach issues and themed experiences there - attest to the greatness of this one difference that has attracted much research interest, especially by the character of difficulty and strangeness of the thought of Dōgen. Such difference may be apprehended in the way each thinker interprets the fundamental feature of time: for Heidegger, as we have seen before, this feature is in the precedence of future (zukunft); for Dōgen, it is in the precedence of precise, exact, immediate and full present (nikon).

By the cosmological feature of the awakened mind, we do not find in the Zen Master two central features of time, present in Heidegger's thought: Time as an exclusively human experience and the precedence of the ekstatic horizon of future. For the Zen Master, neither experience nor time are exclusively human, but they belong to all conscious beings, to those living beings that have any form of consciousness and are impermanently existent. Contrary to the pre-eminence of the future, Dōgen understands that the awakened mind apprehends things in a full and absolute present. There lies here a great difficulty to our Western thought that, used to metaphysical categories, interprets this temporal mode of present as the medieval nunc stans, the simple now or the immobility of the present moment; or even as the aeternitas, the eternity opposed to time. Even Heidegger, who has a great number of contact points with the Zen Buddhist thought, is not an exception to this Western way in the understanding of this guide-term, the full present, as he himself expressed in "The Zollikon Seminars":

[...] the human being's finitude consists in the fact that he is not able to experience the presence of beings as a whole, as what has already been, and as what is still to come as an immediately given presence as a being in a nunc stans. In Christianity, such a thing is reserved for God. Christian mysticism also wanted nothing else. (All Indian "meditation'' also wants nothing else than to obtain this experience of the nunc stans, to realize it as the ascent to the nunc stans, in which past and future are abolished [aufgehoben] into one unchanging present [unwandelbaren Gegenwart]). (Heidegger, 1987, pp. 224)

In this excerpt, Heidegger is very clear about how he interprets the radical religious experience, being it Western (the Christian mystic) or Eastern (the Indian mediation). For the philosopher, they are nothing more than an effort to reach the experience of the nunc stans. In this sense, Heidegger seems to not provide this essential distinction between religious experience and Western tradition of the theoretical-discursive thought, once both, in his opinion, meet each other under the horizon of time, interpreted as a subsistent being, that gives precedence to the present, with constant and inner presence from which were abolished the determining modes of ekstatic time of past and future.

Maybe the main difficulty for us to understand this other possibility of time, the absolute present, is in the fact that it represents, for us human beings – used to the mode of anthropocentric existence and especially to the Western metaphysical thought–the experience of split time itself, once we interpret it, tout court, as an exclusion of past and future that represents the extinguishing of time movement and then nothing more seems to happen in human existence. However, Dōgen paradoxically tells us otherwise. The full, absolute present is the one that includes the other two temporal modes, nothing being left from it, once it is not the mere present mode – of the present indicative where all concepts and utterances of the metaphysical thought are based –, but the full presence, the full realization of time. What is gradually being shown as essential in the difference between the two thoughts is that finite time according to Heidegger – even going further than the mere serial feature of simple ‘nows' and apprehending it ekstatic and circularly –, has just the feature of flowing and continuity, while in Dogen, the impermanent time is both continuous and discontinuous. And it is from this fusion of continuity and discontinuity that emerges the full present, dilated, empty (śūnyatā), that in turn, emerges from the experience of two inseparable happenings: the meditative practice and the fullness of presence.

Masao Abe, another Japanese thinker close to Shin'ichi Hisamatsu of the Kyoto School, tries to extend the comprehension of these two issues of time in Dōgen's explanation by putting them in two dimensions to try to expand the dynamic between the three temporal modes to make more explicit the absolute present. (Abe, 1992, p. 135) In this sense, Abe suggests that continuous time (kyoryaku) would follow a flat dimension of present, past and future, while discontinuous time (nikon) would follow a vertical dimension that goes down eternally in direction to the abyss of nothingness or emptiness (śūnyatā). This would adopt the absolute present of a contradictory moving and resting identity (i.e. making time possible of being a ‘un-passable path') a ‘discontinuous-continuity' or even a ‘un-transmitted transmission'. This way, the absolute present would present, three movements, i.e. it could: (a) move itself forward (irreversible) and (b) move back (reversible) in the temporal modes of past, present and future (horizontal dimension) and even (c) rest in the inner of each temporal mode (vertical dimension). Everything indicates that this is what Dōgen is referring to when, in his Uji, he speaks about this passable and non-passable feature of time:

Being-time has the virtue of passageless-passage (kyoryaku): there is passageless-passage from today to tomorrow, from today to yesterday, from to yesterday to today, from today to today, from tomorrow to tomorrow. This is because the passageless-passage is a virtue of time. Pas time and present time do not overlap one another, or pile up in a row […]

What we can conclude is that the absolute present is showing itself through this contradictory perspective while a passing and non-passing or a continuous and discontinuous being makes the emancipated man time fully flexible, multidimensional, dynamic, allows him to move simultaneously in and through the multiple directions of the temporal modes (past, present and future), showing that the enlightened experience of time is both the fusion and the distinguishing of these modes. In this sense, "all tenses of time interpenetrate, reverberate through and influence one another". (Heine, 1985, p. 181)

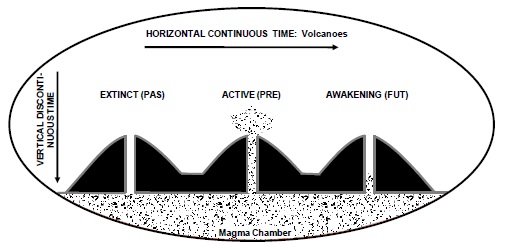

Intending to explain more the dimensions of time (horizontal and vertical) suggested by Abe, giving them a closer picture, we would like to use a drawing taken from geology, knowing from now on of the limits that every metaphor has when trying to explain any proposed understanding. It is about the intrinsic relation between volcanoes that are in the Earth's crust and the magma chamber in the depths of Earth to which the volcanoes are connected. To do so, we will again use the matrix from the previous drawing, which refers to radical impermanence time of numinous dwelling, and upon which we will put the metaphor taken from geology.

The drawing is intended to show both dimensions presented by Abe: the horizontal and the vertical. The top part of the drawing, in which there are the three modes of time, we overlapped them with three volcanoes that, in terms of activity, are distributed in different times: extinct (past), active (present) and awakening (future). They represent, therefore, the horizontal dimension of time, its continuous feature. In the bottom of the drawing, it is the magma chamber, in the deep abyss thousands of kilometers below the Earth's surface. It represents the vertical dimension of time, its discontinuous feature.

The primary idea here is to show the contrast between these two dimensions of time: the horizontal, which suggests continuous time, shown by the volcanic eruptions that happened and will happen in a serial and dateable time and; the vertical, in which is the dimension of discontinuous time, timeless, an eternal furnace of melted rock, under extreme temperature and pressure that has smoked for billions of years. Even here it is easy to understand these two time dimensions because we are interacting with them dualistically, while we contrast them, as it happens in any explanation about any geological theme. But the purpose here, much more difficult, is to see these two times fused in a relation of non-duality that would be, in the last instance, what from Dōgen would be understood of the full, absolute present.

In this sense, we could say that the volcanoes (continuous time) are only what they are because there is a magma chamber in the timeless abyss in the center of the earth (discontinuous time) that sustains them as volcanoes, which means that the datable volcanic eruptions are mere happenings derived from the non-datable abyssal time. But on the other hand, by reasons of temperature and volume increase, the chamber ‘needs' to create volcanoes (i.e. open space to the surface to relieve its internal pressure). The center of the earth, therefore, ‘needs' the existence of volcanoes to continue being as it is. Mutatis mutandis, it is only for this complete interpenetration between continuous and discontinuous time, between the one that has and the other that does not have a date, that we can be closer to those three times affirmed by Dōgen, in the previous quote: the known irreversible time that passes from "today to tomorrow", but also the other two, for us unknown, of time in rest that (does not) passes from "today to today" and of the reversible time that passes from "today to yesterday".

Actually, in Dōgen's perspective, when we abandon every form of duality and are run through by the experience of radical impermanence, there is not truly, "[...] difference whether time does or does not go and come as long as we do not separate ourselves from time, dichotomizing between a permanent ego and time flying away" (Stambaugh, 1990, p. 36) In the same way, from the close relation between the volcano and the magma chamber, as seen in the previous metaphor, it is not important to know which volcanoes erupted, are erupting or will erupt, once both, volcanoes and chamber, are not dichotomized in isolated entities or independent times, for everything belongs to the same bright lava that blazes timelessly (absolute present), being at the top of the volcanoes or in the abyss of the chamber. Both fused together their identities.

Intending to determine even more our comprehension of the emancipated man's absolute present, we will follow another example from Dōgen. Now, his emphasis lies in the feature of discontinuity of time that fuses the before and the after in the happening of the present. It is about the metaphor of the bonfire and the ashes, present in his Genjokōan:

Once firewood turns to ash, the ash cannot turn back to being firewood. Still, one should not take the view that it is ashes afterward and firewood before. He should realize that although firewood is at the dharma-stage of firewood, and that this is possessed of before and after, the firewood is beyond before and after. […] Life is a stage of time and death is a stage of time like, for example, winter and spring. We do not suppose that winter becomes spring, or say that spring becomes summer (Dōgen, 1972, p. 136).

What seems to us more relevant in this observation of the Zen Master is that the idea of changing based exclusively on the interpretation of continuous time is, in the last instance, a representation of the relation of two happenings, an intellectual construction accomplished outside the experience, once birth and death, as bonfire and ashes, apprehended on their original perspective, are beyond this temporal exterior manifestation between past, present and future, once they overtake the temporal categories of a before and an after. But that is not what happens according to man's common knowledge, because for him, the wood becomes a bonfire that, in turn, becomes ashes, in a before and after sequence. For the gaze of the enlightened man, however, Dōgen says what happens is something very different (i.e. wood is wood, bonfire is bonfire and ashes are ashes), suspended from the before and the after. In other words, every happening is the process of one becoming that must be interpreted as a continuous appearing and disappearing (birth and death) of the being-time (Uji) that the Zen Master names, in the Buddhism language, a "position or dwelling of the Dharma" of all things as, for instance, the wood, the bonfire and the ashes.12 Dōgen, therefore, denies the mere continuity, pure and simple, of time, trying to emphasize what for him is more fundamental, the independence of each point or moment of the point.

In other words, the experience of time, in its authentic sense to the Zen Master, i.e. in total interpenetration with the being (Uji – being-time), occurs without leaving the present instant. For this, in order to let this present instant becomes a full, involving presence, it is necessary that the here-and-now of the bonfire fire (nikon) be suspended from the before and the after, without giving rise to abolition. The phases (or positions of Dharma) are independent and, at the same time, flow and pass continuously (kyoryaku). Whence the feature of continuous discontinuity "[...] each cut off from ‘before' and ‘after', and each independent of other being-times yet including them all in itself" (Dōgen, 1979, p. 120, n. 21) in both cases moving absolutely interdependent of the Sum13. The time discontinuity is, therefore, accomplished through the denial of a direct transposition, like a continuous flow, from one happening to another, once in Dōgen's interpretation,

Life is absolutely life, death is absolutely death; spring is absolutely spring, summer is absolutely summer; each in itself is no more and no less – without the slightest possibility of becoming (Abe, 1985, p. 64).

What is observed as fundamental in this comprehension is that Dōgen denies the idea of ‘natural' or direct transmission or transposition between a Dharma position and another. Is there any reason, however, for this denial, affirming the precedence of the independent happening? What is evident is that each moment of time can just pass to the other when denying itself. Thus, in the case of the bonfire, it is needed that the wood ‘auto-denies' itself (dies) to give place to fire, as it is necessary for the fire to ‘auto-deny' itself (dies) to give place to ashes.

This nihilation process between the Dharma's positions, in Abe's interpretation, is "[...] an essential element for the full realization for time itself. Only by the realization of the complete discontinuity of time and the independent moment, i.e., only by negation of temporality, does time become real time" (Abe, 1985, p. 64) And time becomes real by awakening a śūnyatā existential consciousness of the "being-time" (Uji), i.e. the conscience of the things ending at the end of every moment of its accomplishment, making appear the tragic feature of time, experiencing as an eternal fading away, but also, at the same time, the exuberant feature of time, as an eternal innovation, creation and freedom, as well as, in the empty opened by the śūnyatā, new Dharma positions will always appear. However, all these events that we have just presented – such as: the emancipated self, the double time horizon, etc. – are only possible to the man that has emancipated from duality and that has awakened. And the path to this singular happening is the one of continuous, ceaseless practice (Gyōji) – fundamental questions to the multiple perspectives of Buddhism in general and, in particular, for Dōgen that does not tire of warning about such aspect in all his texts.

CONCLUSION

With time interpretation exposure in Dōgen, we are led to the conclusion of this work exposure, whose central purpose was to present a continuum of three modes in human dwelling: the anthropocentric, the existential and the numinous, born, in turn, from three modes of interpretation of the time problem. Moreover, inside this purpose we have tried to emphasize the mode of numinous dwelling in an attempt of presenting the early contributions to its characterization, from an intense and difficult dialogue with the tradition of Zen Buddhism and, especially, with Master Dōgen's thought.

But this was not the only purpose. There is another relevant one which is the fact that Heidegger's thought is in an intermediary place among the three dwelling modes. And this seems a privileged happening. Before Heidegger, the relationship between the anthropocentric and the numinous dwelling made the dialogue between the awakened and the common man something extremely difficult. This difficulty was and still is present in both directions: on the one hand, it is impossible for common man to understand what the master wants to issue in relation to this numinous dimension of existence; on the other hand, it is also difficult for the master to communicate himself what he does not have in his hands but the thinking mode of anthropocentric tradition–full of objectifying notions and concepts and by a logical and discursive language – inadequate and incapable of issuing, which is communicable in relation to the genuine and ineffable feature of the numinous experience. This difficulty, as we have seen it, is due to the fact that both modes of existence (anthropocentric and numinous) are in polar positions and, in turn, they are under two horizons of interpretation of time, also polar (radical permanence and impermanence).

The finitude man, as Heidegger thinks, is immensely nearer the awakened man when compared to a man of permanent time, although it is also demanded from him, as we have exposed before, a radicalization of time interpretation as radical permanence so that the portal of non-thinking opens. However, with the ineffable contribution of Heidegger's thought that has come with the inclusion of his more original apophatic themes like the no, the nothing, the death, to the philosophical discourse, the philosopher represents today a new access path to the problem of being and time until now not experienced by Western tradition thought, since the Greek classical antiquity.

This opening, afforded by Heidegger has, therefore, presented significant contributions to research in the field of religious thought, especially the one that investigates the ground of Western apophatic mysticism, as well as the one that dialogues with the keyword void (śūnyatā) – a central notion of Eastern thought and, in particular, the Zen Buddhism and Japanese thought of the Kyoto School. Such contribution has appeared in the way this new Heideggerian tools (in the form of notions, concepts, categories, etc.), having motivated a great number of scholars – theologians, philosophers and religious scientists, both Western and Eastern –, to make a deep revision work of the categorical and conceptual device used today in the study of questions concerning the comprehension of radical religious experience, present in the mystic living or in the Buddhic awakening connecting, this way, more straightly, bearers and interpreters of this enigmatic and trans-anthropocentric human experience.

References

Abe, M. (1985). Zen and western thought. Honolulu: University Havaii Press. [ Links ]

Abe, M. (1992). A study of Dōgen – his philosophy and religion. Albany: State University of NY Press.

Benoit, H. (1997). A doutrina suprema – segundo o pensamento Zen. S. Paulo: Pensamento.

Derrida, J. & Vattimo, G. (Orgs.) (2000). A religião – o seminário de Capri. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade.

Dōgen, E. (1972). Shōbōgenzō Genjokōan (N. Waddell & Masao Abe, trad e introdução). The Eastern Buddhist, 5(2), 133-40. [ Links ]

Dōgen, E. (1976). Shōbōgenzō Busshō – Buddha-Nature (N. Waddell & Masao Abe, trad e introdução). The Eastern Buddhist, 8(1-2), 87-105.

Dōgen, E. (1979). Shōbōgenzō Uji – Being-Time (N. Waddell & Masao Abe, trad e introdução). The Eastern Buddhist, 12(1), 114-29.

Heidegger, M. (1958). Essais et Conférences – Vorträge und Aufsätze – 1954 (A. Preau, trad. et par J. Beaufret, préfacé). Paris: Gallimard.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Le Principe de Raison (A. Preau, trad. et par J. Beaufret, préfacé). Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1968). La Doctrine de Platon sur la Verité (Platons Lehre von der Wahrheit - 1947). In M. Heidegger, Questions II (A. Preau, trad.). Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1971). Nietzsche - v. II - 1961 (P. Klossowski, trad.). Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1972). O fim da filosofia ou a questão do pensamento (Das Ende der Philosophie und die Aufgabe des Denkens – 1966; E. Stein, trad; rev. J. Moutinho, rev.). S. Paulo: Duas Cidades.

Heidegger, M. (1975). Die Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie (1927) – GA 24. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann.

Heidegger, M. (1976). Brief über den Humanismus. In M. Heidegger, Wegmarken (GA 9). Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1981). Erläuterungen zu Hölderlins Dichtung (1936-68) – GA 4. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann.

Heidegger, M..1987. Zollikoner Seminare, GA 89. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. [ Links ]

Heine, S. (1985). Existencial and ontological dimensions of time in Heidegger and Dōgen. Albany: State University of NY Press. [ Links ]

May, R. (1996). Heidegger's hidden sources – east asian influences on his work (G. Parkes, Trans.). London/N.York: Routledge.

Nishitani, K. (1982). Religion and Nothingness (Shukyo towa nani ka - 1961). (J. Van Bragt, Trans with an introduction; W. L. King, Foreword). Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Otto, R. (1961). Das Heilige - über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum Rationalem. München, C. H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuch-handlung. [ Links ]

Parkes, G. (Org.) (1987). Heidegger and Asian Thought. Honululu: University Havaii Press. [ Links ]

Stambaugh, J. (1976). Time-Being: East and West. The Eastern Buddhist, 9(2), 107-114. [ Links ]

Stambaugh, J. (1990). Impermanence is Buddha-nature: Dogen's understanding of temporality. Honolulu: University Havaii Press. [ Links ]

Version: Rodrigo Popotic

Revision: Adam Crum

Recebido em 17/07/2011

Aprovado em 10/09/2011

1 Graduated in Philosophy and Psychology. Psychotherapist. Master degree in Philosophy at PUC-SP. Doctorate in Philosophy at UNICAMP. Researcher in the Postdoctoral Program at PUC-SP, financed by CNPq.

2 We will prefer, in our work, the guideword of Rudolf Otto's vocabulary – das Numinöse, from his classic Das Heilige of 1917 (Otto, 1961) – to designate the radical feature of religious experience instead of the more common, mythical, for two reasons: on the one hand, it is extremely committed with philosophical and religious systems of metaphysical sustenance and, on the other hand, because Zen Buddhism refuses this denomination, stricto sensu, to refer to the experience of the Buddhic enlightenment. However, as the word ‘mythical' has belonged for a great deal of time in the tradition of the negative theology, we will sometimes use this term when it appears necessary or appropriate, especially because of the citations given.

3 Further in this work, when we refer to the numinous thought, we will give more information about the reasons that made us designate as partial the ekstatic feature of the Heideggerian finite time.

4 This proximity between the holly (das Heilige) and the safe (das Heil) is possible, in a privileged way, by the German language through the verb heilen in its old meaning of letting safe and intact, whole and full, i.e. heal, save, indemnify. Indemnis relates to what has suffered no harm. A derived word such as indemnify often used in law terms, has a original meaning based on religious rituals, while "[...] process of compensation or even restitution, sometimes sacrificial, which reconstructs the intact purity, the safe integrity, a clean and a non-injured property. It is exactly what the word "Indemnis" means: pure, non-contaminated, non-touched, sacred or holly before any profanation, wound, offence, harm. In Heidegger, (it) was chosen, frequently, to translate heilig (‘sacred, safe')" (Derrida & Vattimo, 2000, p. 36, n. 12).

5 Heidegger's references to the word mystic have, as a rule, the negative sense, as a synonym of something dark and biased, as he does, for instance, in (Heidegger, 1971, p. 26) and (Heidegger, 1972, p. 97). But it has a positive sense when connected to the thoughts of Meister Eckhart or Angelus Silesius, as seen in (Heidegger, 1962, pp. 105-06).

6 We believe that this is the reason why Heidegger's thought – especially in the second phase of his path – has been connected to mysticism, mainly by his critics, even those with opposite perspectives. This way, There are those extremely rationalists, unfriendly of mysticism, who see in Heidegger's use of words from the mysticism field proof of the philosopher's failure, putting all his work under suspicion of irrationality. But there are those who criticize Heidegger precisely because they are friendly to mysticism, blaming the philosopher for "illegal appropriation" of expression terms from mysticism, interpreting the late works of the philosopher as arrogant and pretentious, as they expose an explicit desire of being part of the great spiritual tradition of mysticism.

7 Cf. May, 1996. On this work, the author tries to show that the Asian influences in Heidegger's thought do not go any further than his contacts with students from the far east or his known dialogue with the Japanese professor, Tomio Tezuka. Among them there are Heidegger's attempts in translating some chapters of Tao Che King, of Laozi, with the help of Chinese sinologist Paul Hsiao, in October 1947 – cf. Parkes, 1987, p. 93.

8 Even recognizing that the "non-thinking" is the guideword to express the central aspect of the numinous experience, we try to keep the use of the expression "thinking of numinous" because we understand that, despite its ineffable feature, he is always looking for forms of discursive language to transmit the content of such experience. This is the effort in which take place both bearers and interpreters of the numinous experience, whose result is expressed through works of the primary and secondary literature.

9 Although the numinous thought looks at both Western and Eastern mystic thoughts, this present work will deal more directly with the second – constrained to the Zen Buddhism ambit and, more specifically, to Dōgen's thought – and rarely with the first, especially Meister Eckhart.

10 Stambaugh says that this simple and ordinary happening of removing the connector "and" between "being and time" makes "at least for me, Dōgen is so difficult that Heidegger sometimes looks like mere ontological child's play in comparison" (Stambaugh, 1976, p. 110).

11 It is from there our use of the expression "radical impermanence" – which involves both dimensions: permanence and impermanence – to differ it from simple impermanence.

12 The position or dwelling of the Dharma points out each of the happenings that come to existence as expressions of non-duality of the being-time, manifesting itself on each of its stages of appearing, keep in presence and fade away.

13 This Sum is the emerging horizon of all happening and phenomena that are brought to existence by a radical interdependence between them, called by Buddhism as "interdependent arising" (pratītyasamutpāda). The most known metaphor to express the idea of this Sum, given by the school of Hua-yen, is the net of jewelry of god Indra. In this infinite net, which represents the universe, it is an uncountable number of perfect precious stones, each one reflecting the light and brightness that is received from all the others. The lights game there manifested is the result of the reflex in the total amount of precious stones, not finding neither one, between them, whose brightness is in a "superior" position or has the function of "first cause" in relation to the others. It is from this intricateness of the Sum net that emerges the position of each happening (being-time) of the universe and human existence. Whence the expression "position of Dharma" to say that the emerging and the fading away of each phenomenon (position) comes from a Sum (Dharma), from an infinite group of interconnections and interdependencies between all the other phenomena.