Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva

versão impressa ISSN 1517-5545

Rev. bras. ter. comport. cogn. vol.9 no.2 São Paulo dez. 2007

ARTICLES

B. F. Skinners Verbal Behavior: an Introduction

Ernst A. Vargas1

B. F. Skinner Foundation

ABSTRACT

Skinners analysis of verbal behavior requires understanding its experimental and philosophical underpinnings. His interpretation of the social behavior known as language builds directly from the experimental analysis of behavior in direct contact with its immediate milieu, both inner and outer, and from the framing of behavioral contact as contingency relations. The analysis of the contingency relations of verbal behavior, however, deals with properties of behavior not only under the dynamic controls of direct contact, but as that control is mediated by society. A social community constructs that mediation by shaping its members actions to teach other members how to verbalize effectively through the proper forms of action. As such, Skinners attributes of verbal behavior are: 1) relational; 2) mediational; 3) communal; and 4; stipulational. All four are necessary components of his analysis of verbal behavior, and constitute what he defines as verbal behavior.

Keywords: Verbal behavior, Relational, Mediational, Communal, Stipulational

Overture

In Verbal Behavior, Skinner states that a proper introduction for understanding his book is to first read Science and Human Behavior. Quite so. Without understanding the science underlying his analysis of verbal relations, either it would be impossible to make any sense of that analysis, or even worse, what he wrote would be vastly misinterpreted. A passé review by a linguist provides one of the best examples of not taking this advice. The reviewer peered at Skinners analysis through the periscope of a stimulus-response psychology so antiquated it was the very antithesis of Skinners position. As MacCorquodale (1970, pp. 83. 98 ) put it, Chomskys actual target is only about one-half Skinner, with the rest a mixture of odds and ends of other behaviorisms and some other fancies of vague origin . . . an amalgam of . . . outdated behavioristic lore. Even if that stimulus-response interpretation had been up-to-date, it still would have been inappropriate as Skinner had rejected such an inadequate formulation. Asked if he had read that review, it was not a surprise that Skinner answered that he had started to do so, read a few paragraphs, and quit when he saw that it had missed the point. A rather polite response, considering.

This Introduction does not substitute for Science and Human Behavior. Instead, this Introduction contributes the conceptual anatomy that constitutes Skinners analysis of verbal behavior. That conceptual anatomy derives from Skinners Theory of Behavioral Selection. One component of Skinners theory, the analysis of verbal behavior, brings into play the impact of culture. Another component, the experimental analysis of behavior, provides the infrastructure of verbal behavior. The laboratory-based experimental foundations supply the various types of controls that give meaning to the different forms of verbal behavior. But more than just controls are at issue in the understanding of verbal behavior. In addition to those controls, there are the definitional attributes that make up verbal behavior and there are more than one. Verbal behavior is not definable by only one attribute, that of its mediational characteristicas important at that may be. A number of other features are equally important in understanding what Skinner meant by verbal behavior. Giving both the anatomy and the attributes exposes the essentials of what constitutes verbal behavior.

Skinners theory of behavioral selection

The Character of Theory

With regard to a domain of phenomena, a theory is a coherent system of statements from which testable conclusions can be drawn. It ties together the database of a discipline by relating how events that apparently differ share common properties. An apple that drops from a tree shares the same gravitational relations as the moon does to the earth. The deoxyribonucleic acid of a fruit fly turns out a different anatomy than that of a human being though its protein producing mechanisms operate in the same manner. An intermittent schedule of reinforcement produces the same effect in a pigeon pecking at a disc for food as it does in a human pulling at a lever for money. In such a schedule, the species differ, the topographies of behavior differ, even the reinforcers differ, but the dynamic properties descriptive of the relation of action to consequence are the same. The elucidation of similar properties behind the everyday detritus of dissimilar events characterizes the most powerful theories in the physical, biological, and behavioral sciences.

Nevertheless, the term theory has gotten a bad press. At least, the lay public often uses the word theory in a pejorative manner. It is easy to see why. To provide respectability, any half-baked notion is often called a theory. Wild speculations about flying saucers are named theories. Wishful conjectures about arks supposedly found on top of Mount Ararat are called theories. Wayward guesses about a cure for old age are called theories. Not surprisingly for the lay person, the term apparently implies unproven or speculative or merely highly opinionated, but not to the philosopher of science, or the historian of science, or the professional scientist. For a large set of events, theory denotes the powerful explanation through which to reach further insights. They apply the term theory to the highest achievement of scientific endeavor.

A name is usually attached to that achievement: Newtons Theory of Mechanics, Darwins Theory of Evolution, Einsteins Theory of Relativity, Skinners Theory of Behavioral Selection. The name gives credit to the individual who in an integrative fashion described the relevant properties of a domain of phenomena and the database of the science that addresses it. These scientists gained their achievement in a variety of ways. Newtons theory resulted primarily from his experiments. Darwin by and large built his theory from observations of the natural world encountered during his five-year voyage around the world. Einstein constructed his theory from his reinterpretation of the data and theories of the current physics of his day. Skinner derived his theory from his laboratory experiments and from observing and interpreting the lingual actions of everyday social life.

The Framework of Skinners Theory of Behavioral Selection

Thematic foundations: For this Introduction, three themas are pertinent. First : Skinners theory assumes a continuity in the properties of behavior with all types of animal life. Behavior is subject to the same laws regardless of the species in question. Due to differences in anatomy and physiology, animals may differ in the special ways they interact with their environment. Birds fly. People write. But if a bird or a person has not eaten for several days, any action that produces food is likely to be repeated. The contingency relation operates regardless of the species in question. If the action occurs in a particular pattern, then that pattern tends to persist over time as long as the contingency relations remain the same. Second: Skinner asserts that behavior may be described and then explained by the functional interrelation between values of independent and dependent variables. Function is substituted for causality. The philosophical implication of a deterministic framework is avoided. Function denotes its mathematical usagethe paired relation of values of two or more variables. Third: Skinners theory rejects any form of agency as an explicit or implicit causal force. Contingency replaces agency in describing the interaction of actions with inner or outer events at any level of analysis. There is no self, or ego, or I, or for that matter, pigeon or speaker, responsible for an action whether pecking on a disc or tapping on an iPhone. The action is enmeshed in a nexus of contingency relations, and is a vectored consequence of relevant factors such as deprivation and reinforcement as well as phylogenetic history.

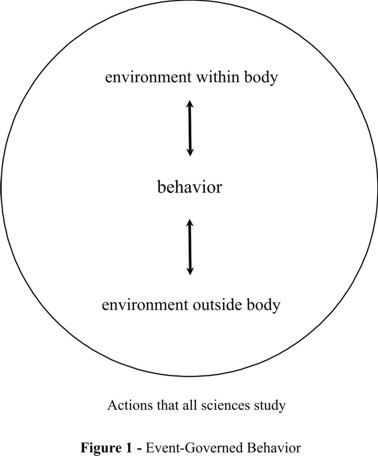

Experimental foundations: Behavior directly contacts both an inner and an outer milieu. (See Figure 1.) These actions are governed by events. All sciences examine event-governed actions.

Event-Governed Behavior

These event-governed actions occur within every domain of phenomena the sciences studyphysical, biological, and behavioral. The physical and biological sciences have studied actions in a scientific manner longer and have analyzed them rigorously in those sciences dimensional frameworks of description and explanation. Skating, for example, can be analyzed with respect to its biomechanical properties. The extended slides of skating give it an advantage over unassisted modes of transport (such as running) because, as it happens, the slower a muscle contracts, the greater the force it develops (Summers, 2007/2008, p. 20). Skating can be also analyzed with respect to the cultural factors involved in racing. And as well, skinnerian science, designated here as behaviorological science, studies skating and also all other actions within its own special dimension of description and explanation.

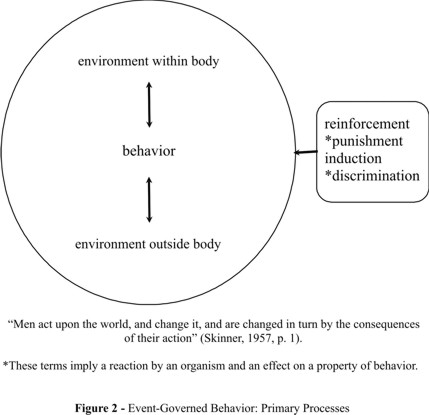

In describing and explaining actions, behaviorological science addresses their contingency relations. The unique nature of these contingency relations, e.g. the operant, provides their meaning. Whether the contingency relation is set within the body or between the body and an external milieu is irrelevant as shown by Silva, Goncalves, and Garcia-Mijares (2007) in a overview of the different levels of neurophysiological events exhibiting contingency selection effects. The same basic behaviorological processes operate. These processes ensue from selection by consequences. Their descriptive names are reinforcement, punishment, induction, and discrimination. Other disciplines study actions differently. Psychological analysis, especially cognitive, of behavior concentrates on the effect of antecedent stimuli on subsequent responses. To correct for the disparity between stimulus and response values, an intervening agency is interposed (Vargas, 1993, October). Behaviorological analysis starts with the effect of postcedent events on a class of actions. The analysis begins with directly observed effects between the values of postcedent stimulus variables and the values of the properties of prior action classes. Postcedent effects either increase or decrease the properties of a prior action class, such as increasing or decreasing its rate. (In current terms, thus reinforcing or punishing the prior class of actions.) With respect to the relational reciprocal effect between action and stimulus classes, the basic two-term contingency relation of an ongoing action class and a postcedent stimulus class is named an operant. The operant can be analyzed as a system, independent of other effects. It can also be, and is, frequently analyzed as a subset of relations within a set of other effects. A given two-term relation may be evoked only in the presence of a certain stimulus class. A narrowing effect of this three-term relation is typically called discrimination. Or, the two-term relation may occur with any of a number of overlapping features of a set of stimulus classes. A subsequent widening of effect is typically called induction. Concurrently, other variables operate to turn physical events into stimulus classes depending on these other variable effects on behavioral properties, e.g. little effort may be made for water until a great deal of salt is ingested or no reaction is made to a light until paired with food.

Event-governed behavior: Primary Processes

Within the framework of contingency analysis, these dynamic processes explain behavioral phenomena and their forms.

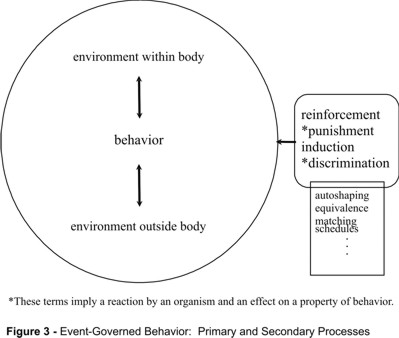

A number of subsidiary behavioral relations depend upon and permute from these basic processes. In conjunction with complex stimulus arrangements, these secondary effects account for further behavioral effects. Contingencies of reinforcement produce specific and predictable outcomes in particular patterns of action. Equivalence relations induce new controlling relations. Matching demonstrates the proportional distribution of reinforcement relations. And so on.

Event-governed behavior: Primary & Secondary Processes

These basic and secondary processes of contingency relations provide the foundations of the interpretation of verbal behavior. Though much has been accomplished, the understanding of verbal behavior with respect to these increasingly complex basic and secondary processes has barely scratched the surface. Any complaint about the inadequacy of Skinners analysis of verbal behavior must first address the issue of the adequacy of the science. And independent of that matter, the science has been successfully extended to the conceptual analysis of verbal behavior, to the experimental demonstration of many of its theoretical propositions about verbal behavior, and to the practical application of teaching verbal behavior.

Skinners Interpretation of Verbal Behavior

Theoretical Attributes

Theories come in all forms and styles. Skinners theory of the primary processes underlying behavioral phenomena was a sprawling affair. He constructed it over many years. He added data and insights as he went along. Driven by what he encountered in his laboratory experiments, by and large he theorized inductively. What he encountered changed his experimental efforts. He altered apparatus. He modified contingency requirements. Only later did he change species, from rats to pigeons, but the contingency processes producing similar behavioral properties proved to be the same. The theory of behavior that resulted was cast over many articles starting with The Generic Nature of the Concepts of Stimulus and Response (1935), essentially a rewriting of his thesis, and finding expression in book form such as The Behavior of Organisms (1938), Schedules of Reinforcement (1957), and Contingencies of Reinforcement, A Theoretical Analysis (1969). These touched on every topic dealing with behavior. But the shape of the theory was never really completed. The manner of presentation of the theory was never a unitary one.

The interpretation of verbal behavior also was constructed over many years, but in contrast had a single inclusive expression. In his autobiography Skinner describes working inductively, arranging and rearranging both facts and categories. But the conceptual frame was by and large taken from the experimental analysis of his laboratory work. Obtained from the actions of organisms dealing with their physical surroundings, these established relations were altered to fit the new requirements posed by a social datum. Though behavioral, language is a cultural phenomenon not a biological or physical one. The fact that language requires a biological and physical substrate is not its crucial distinction. These substrates may be necessary but not sufficient, just as it is necessary to have a pair of legs to walk to the store but that does not provide the sufficient reason why one did so. Without a social community that generationally transmits the behavior acquired by others in the group, no language is possible. Verbal behavior, the individual speakers voicing of language, develops through its contact with the behavior of others whose behavior, in turn, developed through its contact with its social, biological, and physical world. Skinner therefore dealt with a second order type of behaviormutually and concurrently controlled by surrounding physical and biological events, internal and external, and by an ambient culture, socially conveyed. In this overlaid intersect of nature and culture, the behavioral processes discovered in the laboratory turned out to be applicable. Since culture is an extensive elaboration of behavioral relations, verbal behavior exhibited a labyrinthine complexity perhaps greater than its nonverbal counterpart. But the same processes were at work. What was required was to interpret this communal complexity within the framework of his theory. In the singular setting of Verbal Behavior, Skinner provided that interpretation.

Verbal Behavior is an interesting book. Built inductively, it presents its propositions deductively. With respect to Skinners reputation as a non-theorist, such a format is ironic. It should not have been unanticipated for there is a touch of the deductive mode in The Behavior of Organisms, the book establishing the experimental foundations of his theory. The book starts with a parade of dynamic and static laws of the reflex from which the reader should orient himself to what later follows. In Verbal Behavior there is no such commentary of such laws or even of the basic experimental workwith tables, graphs, and equationsthat underlies the analysis of language to follow. Instead, the style is almost literary. It quotes authors, without inserting the citations. If in a language other than English, the quote may be in that language. Footnotes are rare. A number of neologisms appear, quickly defined, with examples bearing the weight of the definition as well as the various aspects of the definitions meaning. Nowhere in sight appear the signs of a hypothetical-deductive system requiring the mode of a propositional calculus. But propositions (and implied hypotheses) there are, and there are plenty of them. Each statement practically calls for a test; not the definitional statements of course. When it is asserted that if someone asks for something and another person gives it to him and then that statement will now be called a mand, one could argue over the label but not over the fact of the observation. The fact merely describes what is known in daily life and what is observed from laboratory study. The reasons under which an utterance occurs is when definition steps over into theoretical formulation.

The reasons, and thus the theoretical formulation, came from basic operant work. Alternative theories have always been present in prior linguistic analysis. In them, meaning came from what was intended, or from any of a number of inferred conditions in the directive agency within the organism. Skinners theoretical formulation radically differed. The organism and its implied agencies (whether self or structure) dropped out as an originating force. Meaning resided in the controlling variables over what was said. What these variables were, and as important the dynamics of how they interacted, was provided by an experimental analysis of behavior. Its linchpin was the operant. The operants postcedent control eliminated the necessity of an initiating agency. (In biology the selection mechanism discards the necessity of an initiating agency in the emergence of the forms and functions of organisms, and so does the selection mechanism in behaviorology drop the necessity of an initiating agency in the emergence of the forms and functions of language.) The operant provides the framework for the mand, where consequences dictate the form and occurrence of that type of verbal behavior. Of course, other variables are involved. Just as in evolution where geographic isolation has a hand in speciation, natural selection is the driving force. In evolution, natural selection initiates the complexity of the factors that interact in the variational process. Similarly in verbal behavior other variables, such as the audience, are always at hand, but selection by consequences is the driving force. One views the effect of prior stimuli only through the lens of the operant relation. Evocative stimuli get their effect after pairing with the operant contingency. The tact, for example, gets its effect through the generalized reinforcement provided to antecedent events paired with lingual operants. Underneath the complexity of the analysis lies the profound simplicity of a few variables, much like the complexity of the immediate physical world rests on the interaction of a few variables such as force, mass, and acceleration. In Verbal Behavior, Skinner provides the theoretic formulation of how the variables relevant to selection by consequences of event-governed activity operate in the social world of lingual-governed actions.

Of his theoretic formulation, Skinner leaves to others to provide its rigorous tests. Quite a few have taken place. Efforts were at first slow. These have now accelerated. In a review of the history of research on verbal behavior, Eshleman (1991) puts it well,

We should not expect operant analyses to come from traditional language researchers. . . . To the extent they deal with behavior at all, they do so from a paradigm other than the selection by consequences paradigm of Skinner. (pp. 73-74)

. . . expecting traditional language researchers to conduct research out of Verbal Behavior is rather akin to expecting theologically-oriented natural philosophers to act as Darwinians and study biology from the paradigm of natural selection. Skinners analysis of verbal behavior represents a paradigm shift, and we should have expected some time lag to occur.

If we actually plot the frequency and celeration of verbal behavior research . . . we find a solid acceleration trend upward. (p.77)

These efforts and tests take place in three ways.

First, the basic theoretical formulation can be conceptually extended. Simply through ratiocination, can a greater utility of Skinners formulation as well as a greater clarity on issues regarding language be achieved? Enlarging the scope of the concepts delineated in Verbal Behavior facilitates an understanding of those concepts and of commonplace activities not otherwise obtained, for example, J. S. Vargas (1978, 1991), E. A. Vargas (1986, 1988, 1991, 1998). Comparisons between Skinners theoretical formulation and those of traditional linguists clarifies the differences and illuminates the issues, for example, Knapp (1990, 1992), Mabry (1993, 1994-1995), Schonenberger (2005). Any casual perusal of this literature encounters an extending of the contingency analysis accented in Verbal Behavior.

Second, Verbal Behavior provides its theoretical formulation in a muted hypothetic-deductive manner. Propositions are asserted. Conclusions derived from them. The case for these propositions made by example and illustration. (Implied in their acceptance is whether one accepts Skinners theory of behavioral selection and its experimental background.) But more than example becomes necessary to prove any proposition asserted in a scientific enterprise. Does an experimental test validate it? Bit by bit, test by test, various hypotheses have been experimentally examined. The results of these experiments continue to confirm the assertions, leading credence not only to those propositions tested but to the entirety of the analysis. A couple of investigations will be mentioned in passing. A first example: One proposition claimed that a verbal utterance emitted under one set of circumstances though appropriate for another could not necessarily be emitted. To put it more familiarly and loosely, simply because a word was known did not mean it would always be available for use. The proposition seems counterintuitive. Once being shown a pencil and taught to say pencil to it, it seems only common sense that when a pencil is wanted that is what is said. That turns out not to be the case. A word learned under the controlling conditions of the tact tends not to be emitted under the controlling conditions of the mand; (tendsvariables such as the audience or processes such as induction also play a part.) The second example: Skinner devotes an important analysis of verbal utterances under multiple control (important, in part, because it forms the basis of what he later explores in autoclitic behavior, and important, in large part, because of the multiple controls in the social setting). Lowenkron (1991) examined and extended this analysis under the label joint control. (He makes, however, a distinction between joint control and multiple causation; e.g., the footnote on page 2 in Lowenkron and Colvin [1992]). I disagree with the distinction: Joint control is a type of multiple causation; the verbal utterance is multiply controlled and as such the probability of its utterance altered. We may have here the usual matter of how we wish to label events.). Lowenkrons work has been followed up nicely by others such as Joyce Tu. Tu (2006) concluded,

Joint control is an event that is independent of any particular stimulus but is specific to the relation {italics added] between stimuli. . . . Furthermore, joint control does not require any new principles or explanations for the behavior of the listener. It simply restates and demonstrates a critical feature of verbal behavior: multiple causation. (p. 931)

Further experimental confirmation or adjustment of Skinners theoretical propositions will follow as researchers invent the new and precise methods by which they can experimentally examine them.

The third type of confirmation was one of greater concern to Skinner (1957):

The extent to which we understand verbal behavior in a causal analysis is to be assessed from the extent to which we can predict the occurrence of specific instances and, eventually, from the extent to which we can produce or control such behavior by altering the conditions under which it occurs. (p. 3)

In short, does his analysis of verbal behavior leads to effective practical action? Certainly the teaching of language to those children where formerly it was not thought possible displays such a test passing with flying colors. Among the many who have carried out this educational effort, two will be mentioned for the extent, quality, and impact of their accomplishment: R. Douglas Greer and Mark L. Sundberg. The work by Greer and Sundberg (and others) consists of developing contingency environments in which language develops and evolves. Their effort is a shift to a variational process analysis and a move away from the dominant essentialist position of the traditional linguist formulation. It is the contingencies evolving the language not the person. (With respect to analysis of the variational process see Lewontin [1982], especially chapter 9 for a quick and clear summary. For more detail and extensive discussion, see Mayr [1991]). Any one of Sundbergs publications would be a good introduction to his behavioral engineering work, but one that would be of special interest to students and others interested in conducting research on verbal behavior would be his article on potential research topics, Sundberg (1991). As with Sundberg, any of Greers articles would be a good starting point but two written with colleagues give a excellent overview of the history and direction of his behavioral engineering effort: Greer and Ross (2004) and Greer and Keohane (2006). In the latter article, they sum their efforts by stating that they identified teaching procedures for,

(a) inducing speech and communicative functions for persons with autism and developmental disabilities, (b) replacing faulty speech with effective communication, (c) teaching self-editing and self-management repertoires for functionally effective writing, and (d) teaching complex problem solving repertoires to professionals such that stronger treatment and educational outcomes resulted for a variety of learners. (p. 141)

As Skinner was a deeply dedicated humanist concerned with the welfare of others, such successful teaching would have pleased him immensely.

Definitional Attributes

People have focused on Skinners definition of verbal behavior as behavior mediated by others. Understandably so. Skinner states that verbal behavior requires a separate treatment due to this characteristic of mediation. Such a position is realistic. How else could verbal behavior, or more broadly language, come about except through the means of the human group? Even if only transmitted genetically, human language would require human progenitors. Though natural selection may operate on the group to develop the substrate mechanisms by which language operates, no natural selection mechanism could produce a language repertoire in an individual in the absence of a group who bequeath their cumulative beliefs and skills due to their encounters with an immediate and past world. The effects of the life histories of persons and groups show themselves in the changes and practices of linguistic activity. (See for example Guy Deutschers [2005] portrayal of how language change plays out socially.) A languageincluding any required genetic codingis not its facilitative substrate. A language is the practices of a group. An individuals repertoire is shaped to those practices. In order to acquire this repertoire, an individual contacts the repertoires of others and is contingently reinforced to their specific forms in relation to events that make that individuals repertoire effective.

Nevertheless, there is more to the definition of verbal behavior than its mediational aspect. As Skinner states (1957), the definition needs, as we shall see, certain refinements (p. 2). The refinements are not stuck out in front like the attribute of mediation. They linger implicitly throughout the entirety of the analysis. Though, perhaps, the word implicit does not quite capture the strength of the other definitional requirements. Already there as part of the initial defining statement, one necessary characteristic is that it is communalmediated through other persons. Such a necessary characteristic is part of the analysis throughout the discussion of all the verbal relations, and finds special expression in the influence of the audience. Another part of the definition is its stipulational requirement. As well as its distinguishing dynamic properties. verbal behavior also has distinguishing topographic properties, forms to which the listener responds and from which controls over the speaker are inferred. And throughout, all verbal relations are defined through the experimental work responsible for the basic processes and relations which give verbal behavior its special characteristics . . . (Skinner, 1957, p. 3). I denote this definitional attribute of verbal behavior under the label of relational, and with it start the description of definitional attributes.

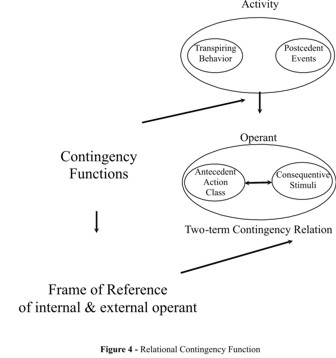

Relational: The relational requirement of verbal behavior ensues from Skinners comprehensive theoretical foundations. All of behaviorological theory pivots on the fact that it analyzes the contingency relations between actions and other events, starting with the postcedent relation of the operant. The significance of each lies in the relation itself. Actions are merely that, with a particular kind of topography defined by their physical and biological status. Events are merely that, with their status defined physically or biologically. The contingency relation between action and event provides to each its behaviorological significance. Food and salivation are biological events significant in nutrition. Food is named an unconditional stimulus when correlated with salivation and that food becomes the occasion upon which salivation occurs. The action of salivation is named an unconditional response when it follows closely the presentation of food. Each event, food and salivation, obtains significance in its correlated relation to the other. An action is an operant only when in a correlated relation with a postcedent event that affects it and when that effect defines the event as a particular stimulus function. Food, for example, is a reinforcer when it follows an action class and increases the probability of its occurrence. When in such a relation, the action class becomes an operant. The significance of action and event is given by their correlative relation. As Skinner puts it in The Behavior of Organisms (1938, p. 9), a modification in part of the forces affecting the organism . . . is traditionally called a stimulus and the correlated part of the behavior a response. Neither term may be defined as to its essential properties without the other. The contingent functions between actions and other events define relational controls. The form of an action takes its meaning from the relational controls over it, and thus these controls provide its interpretation.

Relational Contingency Function

Contingency functions provide the frame of reference by which all actions, including verbal, are interpreted. The interpretation does not depend on intentionality or any other hypothesized state of a presumed agency. The interpretation does not depend on an agency integrating its experiences with events in the environment nor does it depend on a speaker to provide principles and rules to syntax. In sum, it does not depend on a speaker as agency as an originating cause for speech. The speaker is no more an agency for its actions than is the sun when astronomers say the sun rose. The term speaker (as well as the term listener) simply provides a convenient shorthand for the locus at which contingency factors exert their effect. These contingency factors may ensue from within the body as well as from its surrounding milieu. They reflect the ecological, cultural, and genetic history of contingencies concurrently interacting in the present situation. These contingency relations, including the functional interdependence of action and stimulus, frame the dynamic interaction of the verbal episode.

Throughout the analysis of verbal behavior, the variables of which it is a function provide the meaning of any verbal utterance. The processes of reinforcement, punishment, induction, and discrimination exert their controls in the special ways that define the verbal utterances of the mand, tact, intraverbal, and autoclitic. Addressing the functional relations between these processes and verbal forms untangles the different meanings of an identical utterance made at different times, by different speakers, and to different groups. If someone says the word freedom or the word god, what are the controls under which it is emitted? These define the meaning of the term. For the sophisticated listener inferring the terms correct controls (independent of dictionary synonyms), those controls provide the terms significance. They relate the contingent functionality of the utterance (the dependent variable) and its controlling (independent) variables. When mediated, control, and thus the meaning of a verbal utterance, is socially shaped.

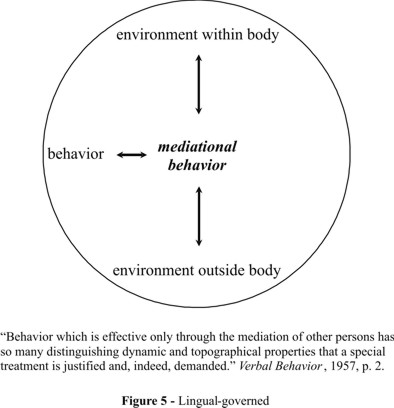

Mediational: Verbal Behavior starts with the sentence, Men act upon the world, and change it, and are changed in turn, by the consequences of their actions(p. 1). Skinner alludes, of course, to behavior governed by its direct contact with its milieu, both inside and outside the body. He moves quickly to another class of actions, actions shaped by its contacts with the actions of other persons and which, therefore, contact the world only through the interposition of such mediated contact. Such mediated contact does not mean that the mediated action so shaped, verbal behavior, does not and will not contact the world directly. It simply means that in that contact it will always carry the effect of its social shaping. The antithetical reactions of different groups to the same events, or to the same agreed facts, illustrate this. Dinosaur bones for the paleontologist represent remnants from a world millions of years ago, and for the creationist those bones represent the release of a creature from an ark after a great flood no further away in time than 4004BC. Both classes of actionsdirect and mediatedoperate through the same dynamic processes of selection by consequences. Shaping of behavior by social contingencies follows the same path as shaping by natural contingencies.

After alluding on page 1 of Verbal Behavior to the experimental foundations of his interpretation of verbal behavior, Skinner moves quickly to its analysis. On the very next page, he describes verbal behavior as behavior effective only through mediated behavior specifically shaped for that effect by a verbal community. With this attribute he emphasizes the social controls of language. Due to their social controls, we can classify these actions as lingual-governed. (Not Skinners term but mine; it extends the terms descriptive of his position, especially to emphasize mediating activity.) Lingual-governed actions contact the same inner and outer milieus that event-governed actions do, but do so through the means of their social origin.

Lingual-governed

Lingual-governed activity is a culturally induced activity, and understood only by taking its social origins into account.

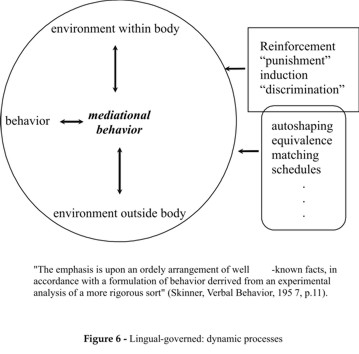

Though there is a social origin to lingual-governed actions, they are shaped by the same dynamic processes that shape event-governed actions.

Lingual-governed: dynamic processes

These processes were derived from Skinners experimental analysis of behavior. As he (1957) puts it quite clearly in the introductory chapter, titled A Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior: The emphasis is upon an orderly arrangement of well-known facts, in accordance with a formulation of behavior derived from an experimental analysis of a more rigorous sort (p. 11). To reject Skinners analysis of verbal behavior would be, in a large sense, a rejection of the science underpinning it. Such rejection would also eschew the philosophical implications of the science, especially the absence (the primary bugbear of its cultured critics) of a free-willing agency in the individual.

Since the analysis is at the unit level of the individual, the behavior mediated is that of the speaker, or who more generally could be called the verbalizer (my term as the behavior mediated may be spoken, written, or gestured). It also would be possible to extend the analysis to other concurrent behavior also mediated. That is, the concurrent behavior of two or more individuals being mediately shaped at the same time. If it were, then the analysis would be at another level entirely, one that would address the macrocontingencies involved over the actions of two or more individuals concurrently. As Skinner (1981, p. 501) put it, Verbal behavior greatly increased the importance of a third kind of selection by consequences, the evolution of social environments or cultures. The effect on the group, and not the reinforcing consequences for individual members, is responsible for the evolution of a culture. This effect can only be analyzed by examining the macrocontingencies bearing on the groups actions, that is, on the joint actions of two or more individuals. (See Ulman [2006] for his definition and discussion of macrocontingency.) The same dynamic processes, however, are in play at both the unit level of the group and of the individual. At the level of the single individuals actions in which the analysis of verbal behavior proceeds, there is, of course, the means by which society affects the individualthe behavior mediating. This role goes by a number of names such as listener, reader, or viewer. The most inclusive term to cover all these various mediational roles (typically defined by communicative modality) is that of mediator (my term).

What further clarifies the mediational connection is to see it in terms of the dynamic interaction of the variables involved and not with respect to the named localities where these variables have their play. The contingency arrangement of verbal behavior is built from the two-term contingency arrangement, the operant. The critical feature is the postcedent stimulus control of a preceding class of actions. If a prior event precedes this two-term relation and evokes it, then it becomes a three-term contingency relation. Both sets of relations describe common, direct encounters with internal and external events. If a socially taught action mediates such encounters, then a four-term contingency relation occurs that describes verbal behavior. The following figure illustrates the four-term relation of verbal behavior.

Verbal Behavior: A four-term contingency relationship

The figure is a bare-bones version of the interaction of involved variables. The dotted lines emphasize the two relevant classes of action and the addition of the action class mediating contact with an immediate milieuthus the basic four terms. Each of these contingency arrangements involves a number of interactive aspects, as well as additional variables that play their part such as the audience variable. The sketchy portrayal, however, facilitates visualizing clearly the four-term relation of verbal behavior due to a mediating term shaped by a verbal community.

Whose behavior is being mediated defines the verbalizer (or speaker or writer or gesturer). Who is doing the mediating defines the mediator (or listener or reader or viewer). As being-shaped and doing-shaping processes shift between individual loci, these processes define their roles. Who is defined as verbalizer or mediator applies to the locus of these quickly shifting processes. For the verbalizer (speaker e.g.) and mediator (listener e.g.) different actions are controlled with a different confluence of variables. For the mediator, for example, no mediated actions are at issue; only the actions mediating. Giving an apple differs from requesting it. No specific way of passing it may be shaped by a verbal community. The person giving it does so with actions shaped by natural selectionreaching, grasping, and so forth. Of course, a community can shape these forms as well. (After a conversation, a person may walk out of a room in whatever way he wants. In the presence of the Queen, he may walk out only backwards with eyes demurely lowered. But then we return to the initial distinction between verbalizing and mediating, between culturally-shaped and non culturally-shaped action forms.) Not only does the stipulated requirement of the action differ, but so do the controls over the different actions. In a mand for an apple, the verbalizer is probably hungry but the mediator may not be. In teaching a tact, the mediator typically knows the name of the object taught, the verbalizer does not. Such difference in controls changes the meaning of the actions involved in the verbal episode. (The shifting aspect of these roles is described by the diagrams Skinner provides in Verbal Behavior.) Though not its only defining attribute, the mediational aspect of lingual behavior is what separates it from other behavior contacting the world. Such mediational contact evolves through a verbal community.

Communal. From the beginning of the book Verbal Behavior to its end, the matter of the verbal community constitutes an inherent part of the analysis of verbal behavior. A final appendix in Verbal Behavior titled The Verbal Community even takes up subtle issues such as the emergence of language in animals and humans. A genetic component is acknowledged. Implied in Skinners analysis is that what matters is the degree of biological transmission of specific forms of utterance shaped and maintained initially through natural and then cultural selection. The problem here is not unlike that in the IQ controversy. Though clearly a biological substrate underlies intelligent behavior, the work by Flynn (2007) shows how tested average levels of the intelligence quotient change generationally as repertoire demands are changed culturally. But there is no necessary antithesis between the selection effects of the two types of community. As Grant (1986) notes in his analysis of finches, Song is a culturally transmitted trait, learned usually from their father in an imprinting-like process (p. xvi). Obviously, a genetical community as well as a cultural community is also involved in the transmission of what may be broadly called communicative behavior. Just for starters, a necessary communicative substrate must be provided to the organism in its anatomy and physiology. This substrate is typically inherited from the genetical community, though in humans the cultural community can compensate for defective and missing parts with prosthetic devices such as hearing aids. And, as in the manufacturing of robots, the cultural community can construct the necessary substrate for communication. The degree to which abstract behavioral forms of communication are inherited is where experts on language differ (e.g. the relations of syntax). There is no disagreement, however, on the necessity of a particular verbal community for a specific language and the approved expressions of it. In the verbal communities of English or Portuguese, a verbalizer speaks English or Portuguese for the mediated pay-off from other members of those language communities. Whether influenced by genetical or cultural factors, there is no escaping the fact that a defining attribute of verbal behavior is that it is communal. Verbal behavior is communal because it is mediated by others, the others of course being members of a culture and thus of that vital facet known as a verbal community.

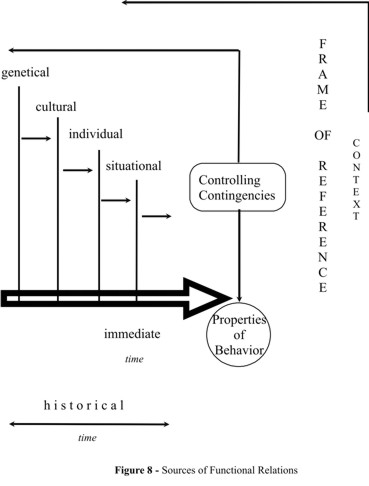

The actions of a verbal community provide part of the complex contingent conditions that bear on verbal events. These contingency conditions were in place already and reflect the sourcesgenetical, cultural, individual, situationalof the functional relations that unroll the variables that take part in the occurrence of any given verbal action. The following figure (see figure 8) represents these sources starkly.

Sources of Functional Relations

With respect to any behavioral property, all these sources bring to bear controlling contingencies that set the frame of reference of its interpretation. Any current situation (which includes its history) shows the effect of whatever variable matters. Not addressing a particular variable with respect to a given action does not imply its unimportance. It simply means that within a given kind of examination that particular variable was not immediately relevant for the analysis of the distinct property of behavior of concern. The pattern of behavior that ensues from a schedule of reinforcement, such as a variable-ratio, can be manipulated (as gambling casinos and animal laboratories do quite well) without addressing the neurological substrate of the organism, whether pigeons or people. The emphasis on a specific set of variables does not imply, nor necessitate, the conceptual exclusion of others.

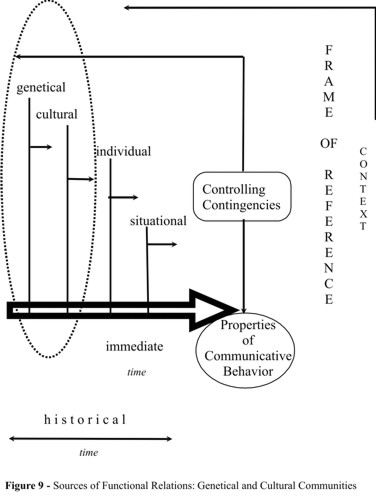

Communicative behavioras mediated behavior and therefore as a special subset of communal behaviorembraces the originating contributions of both the cultural and genetical communities. Where something originates, however, may describe but does not explain. Knowing how an egg is produced requires more than knowing that a chicken produced it. Explanation resides in the dynamical processes responsible for a given outcome. The genetical community exerts its effect through the primary and secondary dynamical processes of natural selection, sexual selection, geographic isolation, genetic drift, and others. The cultural community produces its effect through the primary and secondary dynamical processes of reinforcement, induction, schedule effects, and others. These dynamical processes account for how the genetical and cultural communities shape and maintain communicative behavior, including verbal. Community effects enter into every behavioral transaction of a verbal sort, even within the single individual. The comprehension of symbol and sign, analogy and metaphor, grammar and recursion, occur only as bounded by a community context.

Sources of Functional Relations: Genetical and Cultural Communities

Figure 9 illustrates the relevance of all controlling contingencies, but the greater importance of the cultural and genetical sources in communicative behavior.

Though Skinner (1981) recognized the importance of other sources of selection by consequences, in the analysis of verbal behavior he emphasizes that aspect of the cultural community he calls verbal. But his theory applies to a larger framework of analysis. It is not only the human species that communicates but many others. Primates such as the bonobo, the common chimpanzee, and the gorilla communicate. Other mammals such as dolphins and whales communicate. Birds communicate. Ants and honey bees do so as well. To encompass other organisms, the frame of reference must of necessity be broader. So that, for example, it encompasses as well as distinguishes between the shaping of mediated behavior by natural selection and that by cultural selection. For both types of selection, the broader term communication covers the end result of one member of a species contacting its immediate milieu through the actions of another member. (The etymology of the word communicate unveils a lovely aspect to itto share.) When the controlled contact is primarily cultural, the term verbal designates it, and when the control is primarily genetical, the term signal designates it. We then achieve what Skinner implies: that both the genetical and cultural community shapes, transmits, and sustains the relation between communicational and mediational behavior, as well as stipulates the proper verbal and signal forms of action.

Stipulational: In the Appendix to Verbal Behavior (1957,) Skinner makes the point that, In general, operant behavior emerges from undifferentiated, previously unorganized, and undirected movements (p. 464). Since verbal behavior is a subset of all operant behavior, specific verbal forms also emerge from such ambiguity of action. A verbal community shapes the specific forms of verbal action that control the effective action of the mediator. These verbal forms become the discriminative stimuli to which the mediator responds. As these verbal forms control the mediators actions, they define the meaning of those actions (or in more subtle fashion, the relation between the two designates meaning). With respect to the speakers utterances, these mediator actions are effective only in so far as they subscribe to the functional control under which the verbalizer emitted his verbal behavior. As earlier pointed out, the meaning of the speakers verbal behavior resides in those functional controls. The closer the verbal form reflects those controls over the verbalizer and the closer the mediators action fits the verbal forms implicit or explicit requirement for proper consequences, the more effective the action on both their parts. Lets say, for example, that a husband is in the dining room at the dining room table. His wife is in the kitchen. Though in separate rooms, they can hear each other clearly. He says to her, You know that special sauce for the curry we both like so much? Dont forget to bring it. She replies, Sauce? What do you mean? He then tries to clarify, You know. Its tangy, sort of gingery. Oh, I remember, the chutney. She understands, The chutney. Of course. The specificity of the verbal form that reflects the controls over the husbands verbal behavior now ensures that the wifes action will be effective. The verbal community shapes stipulated verbal forms for effective, practical action.

From the very beginning of his analysis of verbal behavior, Skinner underscores the necessity of these forms. He gives them as part of his initial definition of verbal behavior: Behavior which is effective only through the mediation of other persons has . . . distinguishing dynamic and topographic properties(1957, p.2). As earlier addressed in the Relational section above, the dynamic properties consist of the various controls over verbal behavior that dictate its typesmand, tact, intraverbal, autoclitic, and their subtypes. But as can be noted in the preceding quotation he also mentions the distinguishing topographic properties, and the definitions and descriptions of the various verbal types include form.

The mand: A mand is characterized by the unique relationship between the form [italics added] of the response and the reinforcement characteristically received in a verbal community (p. 36).

The tact: A tact may be defined as a verbal operant in which a response of a given form [italics added] is evoked or at least strengthened by a particular object or event or property of an object or event (p. 82).

The intraverbal 2: These are responses under the control of audible or written verbal stimuli supplied by another person or by the speaker himself. A further distinction may be made in terms of the resemblance between forms [italics added] of stimulus and response ( p. 55).

The autoclitic: It is not enough to point to the presence of autoclitic forms [italics added] in a language (p. 335).

Throughout the analysis of verbal behavior, over and over Skinner brings up the matter of form. A few examples taken by turning pages at random from his analysis in Verbal Behavior (1957) should suffice:

In a . . . verbal community, only certain forms of response are effective (p. 173).

In a given verbal community, however, certain formal properties may be so closely associated with specific kinds of variables that the latter may often be safely inferred (p. 36)

When all the features of the thing described have been taken into account and when the audience has been specified, the form of the response is determined (p. 175).

The relative frequency with which the listener engages in effective action in responding to behavior in the form of the tact will depend upon the extent and accuracy of the stimulus control in the behavior of the speaker (p. 88).

Fable, myth, allegoryin short, literature in generalcreate their own vocabularies by connecting verbal forms with descriptions of particular events or occasions from which they may then be metaphorically extended (p. 99).

Contingencies Determining Form (section head in Chapter 8, pages 209-212 discussing primarily how verbal forms change).

[T]he form is eventually determined by the communitythat is, it becomes conventional (p. 468).

[T]he well established processes of linguistic change will explain the multiplication of verbal forms and the creation of new controlling relationships (p. 469).

We observe that a speaker possesses a verbal repertoire in the sense that responses of various forms appear in his behavior from time to time in relation to identifiable conditions (p. 21).

As he put it when speaking about maintaining the behavior of he mediator, But we have to explain not only the relationships between patterns of response and reinforcements . . . (p. 36). The pattern of a response is its form.

The point was made earlier that the same form may express a different meaning from the verbalizer, depending on the controls over that speech form. So in communication with the verbalizer, an identical form may endow different meanings for the mediator. If meaning for the mediator differs with the same form, how is the proper discriminative control exerted over the mediator? The answer is the usual one of contextor better stated, one of frame of reference. Defining a frame of reference means coming into contact with the contingencies functionally relevant to an action, verbal and nonverbal. A particular verbal form in the absence of further contingency control may not be sufficient for an effective action on the part of the mediator. Additional discriminative control comes about if the mediator comes into contact with the variables responsible for the speakers verbal form. In the presence of the fire place or the firing squad the listener behaves appropriately (knows what the speaker meant) when the speaker says, fire. Often, however, the listener must infer the controlling contingencies over the verbal form, even in the presence of the speaker. A particular history with a verbalizer provides this discriminative control. A child frequently carried up the stairs when requesting to be carried said Carry you? to the parent. The parent responded correctly due to the parents frequently asking the child Do you want me to carry you? before picking up the child to go upstairs. The form may not be the grammatically proper Carry me!, but the controls are clear. The child clearly learned the form Carry you? for being picked up, and then emitted it as a mand. Facial cues, vocal intonation, the whole array of the verbalizers so-called body language provides additional conditional stimuli. The child also stretched out her arms to be picked up. (The if-then principle relevant in changing the meaning of a green light, for example, in a laboratory experiment under conditional stimulus control becomes pertinent here. See Sidmans [1986] article for a good summary of the involved relations.) In either case, directly or by inference, the mediator deals with the controlling contingencies over the speakers verbal form, and though the form may be identical or similar to another, the additional discriminative control clarifies and provides the proper meaning. In addition, the verbalizer may aid the mediator in making an effective response. That is the point of the autoclitic. One set of verbal forms modifies the effect of another, and reinforcement inheres in the mediators behavior becoming more effective. In the descriptive autoclitic, Skinner (1957) supplies the following example, If the speaker is reading a newspaper and remarks I see it is going to rain. the I see informs the listener that it is going to rain is emitted as a textual response (p. 315). In all types of the autoclitic, the verbalizer attempts to inform the mediator the controls under which the verbal form is emitted. The reinforcement contingency that maintains and furthers additional autoclitic forms follows from the mediators greater effectiveness in responding to the verbalizer. (Note the subtleties of the subjunctive.) In the languages of all communities, additional verbal forms are added for sharpening the stimulus control over the mediators responses. That is the function of grammar; in traditional terms it is said to be there to provide clarity and ease of understanding. Grammatical form is especially important in writing where the reader quite often does not observe, much less contact, the contingencies over the writers verbal forms. In conversation, the mediator picks up cues from facial, vocal, and body expressions as well as from immediate events. The requirements of proper verbal form are therefore not as stringent.

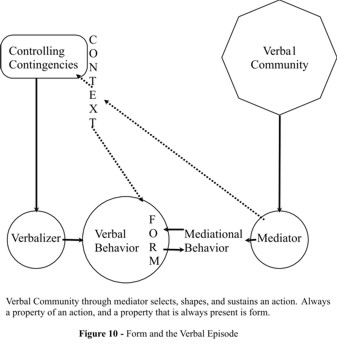

The basics of the relation between stipulated verbal patterns of action can be given by the following figure:

Form and the Verbal Episode

Forms or response patterns constitute part of every verbal exchange, and throughout his analysis Skinner concerns himself, as he put it, to have to explain . . . the relationships between patterns of response and reinforcements (p. 36). The various categories of verbal relationshipsthe autoclitic, the tact, and so onexemplify those explanations. In those relationships, it is as important to understand the role of stipulated forms by the verbal community as it is to understand their dynamic properties. Stipulated forms operate to control mediational behavior as it interacts with the verbal behavior employing those forms. The verbal community shapes the forms of verbal behavior under the appropriate controls. It stipulates those forms for practical, optimal effect by the mediators actions. The title of the movie Lost In Translation captures well the problems that occur when patterns of action, cultural, and more narrowly, verbal, are misunderstood. The characters in the movie did not quite know what the others meant by their speech and deportmentin ordinary terms what they wanted or intendedand found it difficult to take effective action either with respect to themselves or to the other person. They required shared verbal forms carrying the same meaning. (As a metaphorical frame, though the main characters speak English, the entire movie is set in Japan.) The requirements of a verbal community with its resulting conventionalized (Skinners term) set of forms shared among its members establish the array of stipulated verbal forms designated as a language 3.

In the verbal episode, form is a necessary part of the control over the mediators behavior. It does not define the verbal operant. The verbal operant is defined by the dynamic controls over the verbalizer involved in the energetic interrelation between stimulus events and stipulated forms. Stipulated form becomes a discriminated stimulus for the mediators action. A classification system that dealt solely with the mediators behavior would be based on the relation between that prior discriminative stimulus and subsequent mediational behavior. Thus, it would differ from the classification system of the speakers verbal relations. In fact, it would be a classification of nonverbal forms of behavior. A classification system based simply on stipulated forms would be further rarified. It would be a taxonomic description of the verbalizers topographic behavior without any connection to the functional controls (evocative and consequentive) over that behavior. As such it would have to find meaning in the relations between the topographic units (as defined) of the utterances. Without bringing in a functional analysis to explain those relations, metaproperties of those stipulated forms would have to be asserted, principles and rules by which they are manipulated and then by necessity a manipulator of those rules. Perhaps this alternative effort is why so many look for the ghost in the grammar.

Conclusion

All definitional attributes must be part of the meaning of verbal behavior, or else curious conclusions result. If the form of an action is stipulated, that alone does not make it verbal. Requiring proper form to make a particular action effective, a good golf swing for example, does not make it verbal. Stipulated forms that carry meaning for one culture are simply sounds and sights for another. Meaning does not inhere in the structural characteristics of an action. If an action is mediated, that alone does not make it verbal. Many actions are mediatedsuch as disc pecks and lever presses and sit-ups and golf swings. Mediating a food tidbit for a lever press or praise for a sit-up does not make the lever press or the sit-up verbal. If the only definitional attribute of verbal behavior is that it be mediational, then every mediated interchange between any two animals, much less between a human and any other animal, would be verbal behavior. A mediational exchange would then connote a language community, if only of two. But people interpose between an animals actions and its consequences to control and to shape thousands of actions in many species, from ants to zebras. It is far fetched to assert that because such behavior is now mediated with respect to a reinforcing condition that a language is now being taught. If an action is in a relational control condition with respect to another action, that alone does not make it verbal. Actions reinforced (or consequented in any other fashion) by human beings do not make them verbal. Reinforcers are given for a vast array of actions, human and infrahuman. Rewards do not convert those activities into a language or into many discrete languages. Candy may be handed over following a tantrum. That does not make the tantrum a mand. Food may be given to a year-old baby who bangs on a table. That does not make the banging a mand. An action is a mand only when it is in stipulated form as well as under the proper control and when a verbal community has specifically shaped a mediator to bring that form under that control. A distinction must be maintained between the effects of the dynamic processes applicable to all behavior, and those effects relevant only through a culture to the subset of behavior that is linguistic. Knowing these processes, as Skinner (1957) put it, does not mean the work of linguistic analysis can be avoided (p. 44).

Verbal behavior consists of required forms under particular controls mediated through action specifically shaped by a verbal community. With respect to this kind of behavior, it is as yet difficult to clarify our bewilderment and ease our uncertainty. Skinner cleared a path through the supernumerary thicket of activity known as language. We have miles to go before we tame the wilderness of our perplexity. But at least we progress in a promising direction.

Bibliographical References

Deutscher, G. (2005) The unfolding of language. NY: Holt.

Eshleman, J. W. (1991). Quantified trends in the history of verbal behavior research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, pp. 61-80.

Grant, P. (1986). Ecology and Evolution of Darwins Finches. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Greer. R. D. and Ross, D. E. (2004). Verbal behavior analysis: Research in the induction and expansion of complex verbal behavior. Journal of Early Intensive Behavioral Interventions, I.2, pp. 141-165.

Greer, R. D. and Keohane, D. (2006). The evolution of verbal behavior in children. Journal of Speech and Language Pathology: Applied Behavior Analysis, I.2, pp. 1-33.

Flynn, J. R. (2007). What is intelligence? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Knapp, T. J. (1990). Verbal Behavior and the history of linguistics. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 8, pp. 151-153.

Knapp, T. J. (1992). Verbal Behavior: The other reviews. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, pp. 87-95.

Lowenkron, B. (1991). Joint control and the generalization of selection-based verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, pp. 121-126.

Lowenkron, B. and Colvin, V. (1992). Joint control and generalized nonidentity matching: Saying when something is not. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, pp. 1-10.

Lewontin, R. (1982). Human Diversity. NY: W. H. Freeman.

Mabry, J. H. (1993). Comments on Skinners grammar. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 11, pp. 77-88.

Mabry, J. H. (1994-1995a). Review of R. A. Harris Linguistic Wars. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 12, pp. 79-86.

Mabry, J. H. (1994-1995b). Review of Pinkers The Language Instinct. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 12, pp. 87-96.

MacCorquodale, K. (1970). On Chomskys review of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 13, pp. 83-99.

Mayr, E. (1991). One Long Argument. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sidman, M. (1986). Functional analysis of emergent verbal classes. In Thompson, T. & Zeiler, M. D. (Eds.) Analysis and Integration of Behavioral Units. NJ: Erlbaum.

Silva M. T. A., Goncalves, F. L., and Garcia-Mijares, M. (2007) Neural events in the reinforcement contingency. The Behavior Analyst. v. 30 (1) , pp. 17-30.

Skinner, B. F. (1935). The generic nature of the concepts of stimulus and response. Journal of General Psychology, 12, 40-65.

Skinner, B. F. (1957) Verbal Behavior. Cambridge, MA: B. F. Skinner Foundation.

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by consequences. Science, 213, pp. 501-504.

Schnoneberger, T. (2005). A philosophers war on Poverty of the Stimulus arguments: A review of Fiona Cowies Whats Within? Nativism Reconsidered. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21, 191-207.

Summers, A. (December 2007/January 2008). Skating through the ages. Natural History, v. 116, No. 10, pp. 20-21.

Sundberg, M. L. (1991). Research topics from Skinners book, Verbal Behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, pp. 81-96.

Tu, J. (2006). The role of joint control in the manded selection responses of both vocal and non-vocal children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 22, pp. 191-207.

Ulman, J. D. (2006). Macrocontingencies and institutions: A behaviorological analysis. Behavior and Social Issues, 15, pp. 95-100.

Vargas, E. A. (1986). Intraverbal behavior. In Chase, P. & Parrott, L. (Eds.) Psychological Aspects of Language , Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas.

Vargas, E. A. (1988). Event-governed and verbally-governed behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 6, pp. 11-22.

Vargas, E. A. (1991). Verbal behavior and artificial intelligence. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on Verbal Behavior (pp. 287-305). NV: Context Press.

Vargas, E. A. (1993, October) From behaviorism to selectionism. Educational Technology, pp. 46-51.

Vargas, E. A. (1998). Verbal behavior: Implications of its mediational and relational characteristics. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, pp. 149-151.

Vargas, J. S. (1978). A behavioral approach to the teaching of composition. The Behavior Analyst, v. 1, No. 1, pp. 16-24.

Vargas, J. S. (1991). Cognitive analysis of language and verbal behavior: Two separate fields. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on Verbal Behavior (pp. 197-201). NV: Context Press.

Recebido em:12/11/2007

Primeira decisão editorial em: 21/11/2007

Versão final em: 26/11/2007

Aceito em: 22/04/2008

1Ph.D. Vice-President & Academic Officer of B. F. Skinner Foundation. My thanks to Dr. Jerry D. Ulman and to Dr. Julie S. Vargas for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of this article.

2 For this category, Skinner uses the phrase Verbal behavior under the control of verbal stimuli. Such a category name-phrase is clumsy. Ive relabeled the category as intraverbal, and the three primary subtypes of controlling relations as codic, duplic and sequelic. For further detail, see Vargas (1986). Later (Notebooks, 1980, page 361) Skinner defines intraverbal as verbal behavior under the control of other verbal behavior; exactly the position taken in my reworking of the category

3 As an extension of Skinners position, the relation between stipulated form and dynamic controls is quite at issue in the debate over whether primates other than the human being have languagethe practices of a given verbal community. The debate has concerned itself too much with the structure or form and its implied meaning, through intention and syntactical relation. of the utterance or set of utterances examined. It has not much examined: the dynamic interactions between functional controls and mode of the stipulated form, the ambiguity of the controls in the interactions between members of two different species (and the implications for common verbal communities) as verbalizers and mediators, and the successive stage-levels with their differing controls in which identical verbal forms may be emitted so that at one level (primary versus secondary) there may be verbal behavior but not at another.

Deutscher, G. (2005) The unfolding of language. NY: Holt. [ Links ]

Eshleman, J. W. (1991). Quantified trends in the history of verbal behavior research. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, 61-80. [ Links ]

Grant, P. (1986). Ecology and Evolution of Darwins Finches. NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Greer. R. D. & Ross, D. E. (2004). Verbal behavior analysis: Research in the induction and expansion of complex verbal behavior. Journal of Early Intensive Behavioral Interventions, I.2, 141-165. [ Links ]

Greer, R. D. & Keohane, D. (2006). The evolution of verbal behavior in children. Journal of Speech and Language Pathology: Applied Behavior Analysis, I.2, 1-33. [ Links ]

Flynn, J. R. (2007). What is intelligence? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1990). Verbal Behavior and the history of linguistics. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 8, 151-153. [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1992). Verbal Behavior: The other reviews. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, 87-95. [ Links ]

Lowenkron, B. (1991). Joint control and the generalization of selection-based verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, 121-126. [ Links ]

Lowenkron, B. and Colvin, V. (1992). Joint control and generalized nonidentity matching: Saying when something is not. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, 1-10. [ Links ]

Lewontin, R. (1982). Human Diversity. NY: W. H. Freeman. [ Links ]

Mabry, J. H. (1993). Comments on Skinners grammar. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 11, 77-88. [ Links ]

Mabry, J. H. (1994-1995a). Review of R. A. Harris Linguistic Wars. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 12, 79-86. [ Links ]

Mabry, J. H. (1994-1995b). Review of Pinkers The Language Instinct. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 12, 87-96. [ Links ]

MacCorquodale, K. (1970). On Chomskys review of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 13, 83-99. [ Links ]

Mayr, E. (1991). One Long Argument. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Sidman, M. (1986). Functional analysis of emergent verbal classes. In Thompson, T. & Zeiler, M. D. (Eds.) Analysis and Integration of Behavioral Units. NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Silva M. T. A., Goncalves, F. L., and Garcia-Mijares, M. (2007) Neural events in the reinforcement contingency. The Behavior Analyst, 30 (1), 17-30. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1935). The generic nature of the concepts of stimulus and response. Journal of General Psychology, 12, 40-65. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1957) Verbal Behavior. Cambridge, MA: B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by consequences. Science, 213, 501-504. [ Links ]

Schnoneberger, T. (2005). A philosophers war on Poverty of the Stimulus arguments: A review of Fiona Cowies Whats Within? Nativism Reconsidered. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21, 191-207. [ Links ]

Summers, A. (December 2007/January 2008). Skating through the ages Natural History, 116, (10), pp. 20-21. [ Links ]

Sundberg, M. L. (1991). Research topics from Skinners book, Verbal Behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9, 81-96. [ Links ]

Tu, J. (2006). The role of joint control in the manded selection responses of both vocal and non-vocal children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 22, 191-207. [ Links ]

Ulman, J. D. (2006). Macrocontingencies and institutions: A behaviorological analysis. Behavior and Social Issues, 15, 95-100. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1986). Intraverbal behavior. In Chase, P. & Parrott, L. (Eds.) Psychological Aspects of Language. Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1988). Event-governed and verbally-governed behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 6, 11-22. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1991). Verbal behavior and artificial intelligence. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on Verbal Behavior (pp. 287-305). NV: Context Press. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1993, October) From behaviorism to selectionism. Educational Technology, 46-51. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1998). Verbal behavior: Implications of its mediational and relational characteristics. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 149-151. [ Links ]

Vargas, J. S. (1978). A behavioral approach to the teaching of composition. The Behavior Analyst, 1 (1), 16-24. [ Links ]

Vargas, J. S. (1991). Cognitive analysis of language and verbal behavior: Two separate fields. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on Verbal Behavior (pp. 197-201). NV: Context Press. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em