Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva

versão impressa ISSN 1517-5545

Rev. bras. ter. comport. cogn. vol.9 no.2 São Paulo dez. 2007

ARTICLES

B. F. Skinners analysis of verbal behavior: a chronicle1

Ernst A. VargasI, 2 ; Julie S. VargasI, 3;Terry J. Knapp II,4

I B. F. Skinner Foundation

II University of Nevada, Las Vegas

ABSTRACT

A time line of Skinners work on verbal behavior must start at the very beginning of his scientific career. Skinner laid down the conceptual framework of his Theory of Behavior as early as his thesis. He developed his experimental work within this framework, and depended on research results to adjust and modify his theory. At the same time, he initiated efforts to interpret verbal behavior within his theoretical formulations and upon the operant relations he discovered in the laboratory. Work on both mediated and nonmediated relations entwined throughout his career. He discovered the basic verbal relations slowly and inductively over a twenty-five year span of effort.

Keywords: Skinner, Verbal behavior, History, Theory.

Introduction

Skinners writing of Verbal Behavior took place over many years, in many settings, and with continuous revisions. More importantly, it took place within the implicit framework of his theory of behavior, primarily based on the process of behavioral selection. Equally significant, its development derived from an intertwining of experimental and naturalistic observations. From the beginning, the interlacing of unnoticed theory and observed fact show themselves consistently.

Skinner insinuates their dual presence when he states at the very start of Verbal Behavior The present extension to verbal behavior is thus an exercise in interpretation rather than a quantitative extrapolation of rigorous experimental results (Skinner, 1957, p. 11). He announces more clearly the type of analysis by further stating, The emphasis is upon an orderly arrangement of well-known facts, in accordance with a formulation of behavior derived from an experimental analysis of a more rigorous sort (Skinner, 1957, p. 11). From the beginning, it was an effort about which he was quite explicit as he stated in a letter to Fred Keller, What I am doing is applying the concepts Ive worked out experimentally to this non-experimental (but Empirical) field (Skinner, July 2, 1934). But the guiding assumptions of his theory of behavior were already present. With his doctoral thesis of 1930, the theoretical effort started early. It continued to the very end. But we take the story only to 1957 and only with respect to his effort on the analysis of verbal behavior.

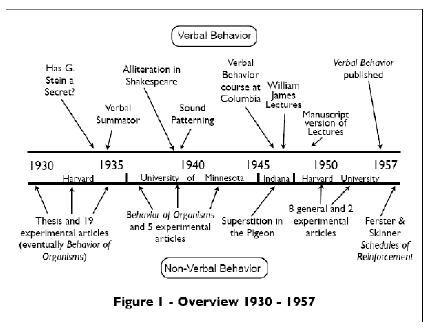

Figure 1 provides a brief overview of the intertwining of experimental and naturalistic work within his theory. Throughout his career, Skinner addressed issues within the lingual area and within the straightforward operant work of the laboratory. The reader can note that 1957, the year his theoretical work on contingencies over lingual actions, Verbal Behavior, was published, was also the same year he, along with Charles Ferster, published the magnum opus on laboratory controlled contingencies, Schedules of Reinforcement. The reader should also note that from the beginning Skinner actively pursued his analysis of language and of nonlanguage behavior concurrently.

Early Work: late 1920s and early to mid 1930s

Though not stated in an orderly fashion nor necessarily in explicit manner, Skinners earliest work, including his thesis, lays out the assumptions by which he later interprets his experimental and naturalistic observations. Several premises or themas guide him. (See Holtan [1973/1988] for a technical discussion of how themas steer scientific theory). Skinner echos them later in his interpretations of experimental observations of behavior and of naturalistic observations of verbal behavior. These premises formed the underlying framework of his incompletely articulated theory of behavior. All of his work on verbal behavior fell within the framework of his theory.

Thematic beginnings of the theory

Skinner submitted his thesis on December 19, 1930. The first half was theoretical; the second was experimental 5. The theoretical half was in the form of a review of the history of the reflex. He sounded the keynote for the review at its start: All the early work on the reflex, from Descartes through Marshall Hall and others, was an attempt to resolve, by compromise, the conflict between observed necessity and preconception of freedom in the behavior of organisms (Skinner, 1930, p. 9underlined emphasis Skinners). He noted that the compromise was due to a

crisis in the history of the metaphysical concepts that dealt with the same phenomenon 6. [T]he movement of an organism had generally been taken as coexistent with its life and as necessarily correlated with the action of some such entity as soul 7. The necessary relationship between the action of soul and the contraction of a muscle, for example, was explicit. As a consequence it was disturbing to find, experimentally, that a muscle could be made to contract after it had been severed from a living organism or even after death (Skinner, 1930, p. 10).

Skinner rejected such a compromise. From the beginning, he dismissed any notion of an agency as a guiding force in the behavior of any organism. Early workers (e.g., Descartes, and afterward even evolutionists such as Wallace) drew a demarcation line between humans and other animals 8. But like Darwin, Skinner maintained the continuity of shared properties between the human species and other species. He was already setting the stage for the speaker as a locus not an initiator. As he subsequently put it at the end of his book Verbal Behavior (p. 460), I have found it necessary from time to time to attack traditional concepts which assign spontaneous control to the special inner self called the speaker. All his work dealt with contingency relations. As an explanatory force, contingency replaced agency.

The term contingency only shows up later, past his thesis work. Initially in his thesis, Skinner emphasized correlation. But it was not correlation in a statistical sense that he emphasized. It was the correlative relation between two (or more) events. As he explicitly stated (Skinner, 1930, p. 37) . . . a scientific discipline . . . must describe the event not only for itself but in its relation [italics added] to other events. This relation assigned the meaning of an event through how it connected to another event. He provided a clear example.

When we say . . . that Robert Whytt discovered the pupillary reflex, we do not mean that he discovered either the contraction of the iris or the impingement of light upon the retina, but rather that he first noted the necessary relationship (italics ours) between these two events (Skinner, 1930, p. 24).

No event is a stimulus independent of its relation to another event called a response, and no event is a response independent of its relation to another event called a stimulus. Each of these events could be described physically, and as such within the dimensional framework of the observational system of physics, but the paired events derive meaning from their relationship to each other. A light is not a stimulus unless and until an action occurs with respect to it and only then can the action be termed a response. All the verbal relations he later described require a similar analysis, for example, A mand is characterized by the unique relationship [Italics added] (Skinner, 1957/1991 p. 36). The connection between two events designates their relationship, a relationship which can be named for its properties. The operant, upon which he built all later analysis, is such a correlative relationship based on the control between a postcedent set of events and a prior action class. Correlative relationships supply the frame of reference by which events are interpreted.

The frame of reference in which events occur provides their meaning. Skinner approaches the problem of frame of reference elliptically, but with respect to his philosophy of science, sidles up to it in a sophisticated way. The definition of the subject matter of any science . . . is determined largely by the interest of the scientist . . . We are interested primarily in the movement of an organism in some frame of reference. As part of that frame of reference, Skinner includes internal events. We are interested in any internal change which has an observable and significant effect upon this movement. In special cases we are directly interested in glandular activity (Skinner, 1930, p. 37). He continues this emphasis upon frame of reference in The Behavior of Organisms (1938, p. 6), describing and amplifying its significance for the subject matter of a science of behavior, By behavior, then, I mean simply the movement of an organism or of its parts in a frame of reference provided by the organism itself or by various external objects or fields of force [italics added]. The stage is set to consider any size, level, and type of contingency relation both within and surrounding the organism, and interactive between those two settings. As Vargas puts it,

The extraordinary range and flexibility of verbal behavior occurs through induction of the overlapping properties of the behavioral, biological, and physical events involved both inside and outside the body. The shifting variability of these properties, and thus of their relations, guarantees that the relationship between terms is not linear and not mechanistic; and other characteristics of Skinners system of verbal relations also make verbal occurrences probabilistic. Terms may be paired with each other (as with an operant) and nest within other relationships (the same operant within a number of three and four and N term relationships). Whether a speech episode occurs depends upon the probability of any of the nested relationships occurring (Vargas, 1992, p. xx).

As reflection reveals, verbal behavior is a four-term contingency relation that builds upon the prior two and three term ones. These contingency relations are the pairs of correlative variables that frame the meaning of lingual interaction.

A frame of reference indicates that it is categories of variables that are at issue in analyzing behavior, not a causal agency. In the analysis of verbal behavior, frame of reference gets its operational workout through Skinners definition of meaning. But meaning is not a property of behavior as such but of the conditions under which behavior occurs. Technically, meanings are to be found among the independent variables in a functional account, rather than as properties of the dependent variable (Skinner, 1957/1992, p. 14). Examples of this sort of framing proliferate throughout Verbal Behavior. For example, the word fire changes its meaning depending on the circumstances of its utterance, a firing squad or burning wood. Puns and other playful attributes of language depend on the tension between the topography of the dependent variable and its implied meaning, with the actual meaning given by the circumstances of its saying. Speakers and listeners constantly attend to those circumstances. As Skinner puts it, When someone says that he can see the meaning of a response, he means that he can infer some of the variables of which the response is usually a function (Skinner, 1957/1992, p. 14).

Function occupies a special place in Skinners analysis of verbal behavior. He does not intend purpose or usage or any other kind of teleological overtone. As he later stated, The strength of behavior was determined by what had already happened rather than what was going to happen in the future (Skinner, 1979, p 203). Of course, that is a presumably going to happen for though we can predict the future we cannot know it. (Unfortunately, the drift to teleological meaning is beginning to occur in the behavior analytic literature, especially that literature concerned with practices with clients. Behavior analysts should object to an interpretation based on the function of a behavior.) Skinner uses the term function in the sense that it is used in mathematics, as simply the expression of a set of paired values between independent and dependent variables. This definition led him to, or stemmed from, the philosophical position of Ernst Mach, which he adopted early. [W]e may now take that . . . view of explanation and causation which seems to have been first suggested by Mach . . . wherein . . . explanation is reduced to description . . . (Skinner, 1930, p. 38). Certainly that kind of explanation occurs if all observed values of independent and dependent variables are provided and their paired relationships are specified. As Skinner points out, the concept of function gets substituted for the notion of causation. He carries Machs position further though. Simple description reports the topography of behavior. Explanation, however, is a more complex endeavor. It asks what conditions are relevant to the occurrence of the behaviorwhat are the variables of which it is a function? (Skinner, 1957/1992, p. 10). It is no accident that Chapter 1, in Part I: A Program, is titled: A Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior.

Within these thematic borders, all later observations, both naturalistic and experimental, were at minimum implicitly explained.

Experimental beginnings of the theory

Skinners thesis started with an examination of the reflex correlation, but soon moved from there. The reflex correlation consisted of antecedent stimulus and subsequent response, and emphasized antecedent control. He designed a series of experiments that began by looking at the response to a carefully calibrated click. When nothing interesting appeared, he scrapped the equipment and built another apparatus for a different procedure. A big step occurred when he automated the recording in a rectangular runway so that the organism, not the experimenter, initiated each run. It permitted a measurement of rate of response, impossible in a trials procedure. By Skinners second year of graduate school, the arranged antecedents had moved from the momentary stimulus of a click to hours of food deprivation. His dependent variable became rate of eating. Each push on the food door of the apparatus produced an upwards movement of a stylus on a steadily moving piece of smoked paper. The resulting cumulative record showed rate in the angle of the line. It also recorded behavior in real time. The results from this apparatus gave Skinner enough data for his thesis.

Continuing to do research, Skinner replaced the door with a lever; shifting from looking at ingestion to lever pressing. With the lever, no longer did each action automatically produce one bit of food. Now more than one response could occur before food became available. The significance of this procedure began to be apparent when the feeder jammed and the animal continued to press the bar, producing a beautiful extinction curve. It did not take long before Skinner realized that, while the third variable of deprivation was important, the real power over rate of responding lay in its relation to how immediate postcedents were programmed. Skinner was excited about his discovery and how sharply it differed from traditional psychology. He evidently wrote his best friend, Fred Keller, about its conceptual implications. Skinners letter no longer exists. But Keller replied, The only thing that bothered me about your very welcome and newsy letter was that talk about a brand new theory of learning (Keller, October 2, 1931). With the discovery of postcedent control (the operant, as Skinner later named it), the first glimmer of a new theory had been sighted. (As the basis of the mand, he later showed its powerful extension to verbal relations.)

The first mention of the operant type of relation appears to be in Skinners article, Two types of conditioned reflex and a pseudo type (Skinner, 1935). He made a rough-hewn set of distinctions between different types of conditioning procedures, whose details need not concern us here. A challenge by Konorski and Miller in 1937 to his initial distinctions prompted Skinner to reply, The differences between the types given in my paper . . . which need not be repeated here, are no longer useful in defining the types [italics ours], but they serve as convenient hallmarks (Skinner, 1937, p. 274). In this reply, he sharpened the distinction between respondent and operant conditioning, and first named the latter the operant. I shall call such a unit an operant and the behavior in general, operant behavior (Skinner, 1937, p. 274). It was to be the linchpin of his theory of behavior, within which he would interpret all behavioral phenomena including verbal behavior. It elucidated an endeavor in which he had already embarked.

Beginnings of Language Analysis

Skinners specific start on language happened accidentally. He began a serious and systematic effort on the problem of language following a friendly and spirited discussion on the relative merits of behaviorism with Alfred North Whitehead 9. Whitehead finally conceded during their discussion that behaviorism might deal effectively with all aspects of behavior with the exception of one, language. Following a dinner, they lingered at the table. Whitehead challenged Skinner to account for Whiteheads saying, No black scorpion is falling upon this table. The very next morning Skinner started the first outlines of his analysis of language. It was 1934.

We catch glimpses of his efforts, and of his intertwining of experimental and lingual work. On July 2, 1934, in the middle of a letter to Fred Keller, Skinner mentions . . . running off a single experiment, but above all writing a book on language from a behavioristic standpoint . . . and now have about ten chapters outlined (Skinner, July 2, 1934). His procedure was Baconian. In my room in Winthrop House I fastened some large sheets of cardboard together with key rings and begin to formulate what I was calling verbal behavior. . . . I took instances of behavior from my reading or from overheard speech . . . and entered them into an awkward and constantly changing classificatory scheme (Skinner, 1979, p. 151). About a half year later, in another letter dated January 18, 1935, he writes, Im going into aphasia, now, on the pathological side of language. A couple of months later, in a letter dated March 15, 1935 evidently in answer to an invitation by Keller to present a paper Skinner provides a peep into the complexity of his linguistic labor by writing, I think the subject had better be experimental. I couldnt say enough on language in an hour to get the point of view across (Skinner, March 15, 1935). He was quite cognizant already of the radical position he was taking. As he stated in another letter to Fred Keller on June 21, 1935,

The book is going to be good. The linguists will laugh at it -- most of em -- and the psychologists wont get through it. But its good. Underneath what seems like a lot of complexity (which is really only novelty) there lies an immense simplification.

He also mentioned that at that time he was working six hours a day on the book. He felt that he was making good progress, sufficiently so to start talking about his analysis By November I was far enough along to offer a colloquium at Clark University on Language as Behavior (Skinner, 1979, p. 158). He engaged not only in theoretical work on language, but also attempted to experiment with lingual behavior. He apprised Keller by letter, Im also building a rather elaborate apparatus for experiments on humans. I call it a Verbal Summator (Skinner, September 25, 1935). He later published an article based on this laboratory work (Skinner, 1936).

Along with his linguistic work, Skinner concurrently pursued his basic operant research. A number of articles based on experimental work on contingency relations were published by him along with those on language. He now took an action he called, strategic. Ive had a long run and tiring run of experiments . . . lot of new dope. During January Im going to whip it into shape along with the general outline of the experimental book. Im going to publish that before the language book for various strategic reasons (Skinner letter to Keller, December 6, 1936). We can only speculate as to why. A plausible notion is that he wanted to establish his credentials as a hard headed scientist before advancing a highly theoretical and sure-to-be controversial analysis. This sort of caution is not unusual. A century earlier, Darwin faced the same problem of acceptance of his theory of natural selection. His friend, Joseph D. Hooker 10, recommended that he not publish until he establish his bona fide credentials as a knowledgeable and hard-headed biologist by producing a work of taxonomic classification. Hooker wrote to Darwin, no one has the right to examine the question of species who has not minutely examined many (Stott, 2003, p. 243). Darwin did, and composed his multi-volume work, still canonical, on the cirripedia. Much the same advice was given to the young Skinner by Crozier 11, his mentor. The theoretical treatment of these questions will be very much stronger and much more effective when backed up by hard analysis of new experimental results.), and a day later wrote, . . . people are very likely to take the attitude that such a treatment as you have given represents merely the activity of another theorist (Crozier, June 3 - 4, 1931). Skinner obviously went along with Croziers advice.

The analysis of verbal behavior rests on the foundations of the analysis of operant behavior. To understand the former, the latter must be known. Though the processes are the same, the critical distinction between the two is that nonmediated operant behavior directly contacts its surrounding milieu (whether inner or outer) whereas in verbal behavior the contact of that milieu is mediated. As Skinner forcefully put it in the beginning of Verbal Behavior , Men act upon the world, and change it, and are changed in turn by the consequences of their action (Skinner, 1957, p. 1). He contrasts this description of operant behavior that directly contacts its immediate milieu with that of the interpolated contact of verbal behavior on the very next page. Behavior which is effective only through the mediation of other persons has so many distinguishing dynamic and topographical properties that a special treatment is justified and, indeed, demanded (Skinner, 1957, p. 2).

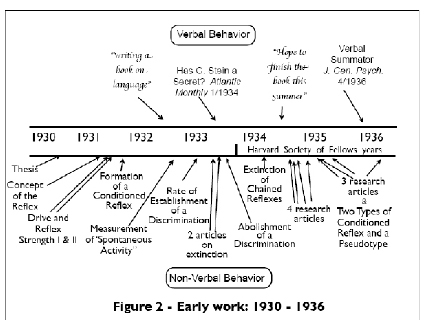

Figure 2 summarizes intertwining of his language and nonlanguage work.

Middle Period: 1936 to Late 1940s

From Language to Verbal Behavior

In 1936 and 1937, Skinner was working on The Behavior of Organisms. This work presented the foundations of his science. It did not as such establish it, for the full scope of his behavioral theory was not seen, even by Skinner himself. (It was construed, at least by other behavioral scientists, as one of the theories of learning of that time, to be taken seriously along those of a half dozen others.) But it did provide the concept of the operant, and its experimental underpinnings. His theory further related this two-term postcedent relation to other behavioral processes such as discrimination and induction. The two-term contingency relation with its postcedent control thoroughly revised the analytic frame in which behavioral phenomena were interpreted. It radically departed from the stimulus-response formulation, based on antecedent control, that had dominated American psychology. Skinner took this postcedent selectionistic relation and built all later formulations upon it, including his interpretative analysis of language.

As he had before, Skinner concurrently pursued both the experimental foundations of his science and its extension to his examination of verbal behavior. He evidently found it an effort to do both at the same time. He expressed some degree of frustration at not being able to put the basic formulation in place and then move on to its explanatory application of language. As he wrote to Fred Keller towards the end of writing The Behavior of Organisms, Im afraid Im going to skimp on the drive chapter out of desperation to get the damn book finished. Im very anxious to get to work on language. Have had a seminar on it this quarter and various people are interested here (Skinner, April 19, 1937). The various people here were evidently members of his own department at Minnesota, for in the summer of 1937, the year prior to publication of The Behavior of Organisms, and in the summer of 1939, the year following the publication of The Behavior of Organisms, he taught a course called Psychology of Literature. He seemed to have gotten distracted into a psychological approach to language. The course covered, among other topics, Fundamental processes involved in the creation and enjoyment of literary works. . . . Psychological basis of style; nature and function of metaphor; techniques of humor, etc. (Skinner, 1979, p. 207). In that summer of 1939, he also taught a radio course in the Psychology of Literature and before that, had given a lecture to the Womens Club of Minneapolis. Such activity implies an effort on his part to get his point of view across to the general public. But it was still largely a traditional point of view, for in his courses and lectures he did such analyses as Oedipal mother-love in Margaret Ogilvy and Oedipal father-hatred in The Brothers Karamazov (Skinner, 1979, p. 208) During this same period, he published an article on alliteration in Shakespeare (Skinner, 1939). Interestingly enough, the articles conceptual point of attack was statistical. Little of his theoretical framework shows itself. It could have been written by anyone who had a tendency to count the use of words in poetic discourse to understand their significance. It comes across as a structural analysis. But it did echo a minor note in his analysis of verbal behavior, and that is, the distinction between formal and thematic control. He was attempting, as he mentioned in a letter to Fred Keller , A statistical study of formal and thematic perseveration (Skinner, November 14, 1938). He did not succeed.

Evidently there was a tug in his repertoire in two directions. He still showed a tendency to analyze literature in the traditional psychological manner. At the same time, there were also his alternative efforts to construct a completely new way of analyzing language, however manifested. The tug reflected itself acutely in his attempt to write up his radio lectures and publish them, perhaps as a small book as suggested by Harry Murray. Even though, as he said, not much of the material was original, he worked hard at the effort and wrote for three or four hours every morning (Skinner, 1979, p. 243). He finally gave up. As he said of his manuscript,

But I was tired of it. I had borrowed the psychoanalysis of Lewis Carroll, J. M. Barrie, D. H. Lawrence, and Dostoevski from other writers, and my own work on alliteration and metaphor was concerned with the decoration rather than the content of verbal behavior. . . . Six months later I would be writing, Im almost ready to undertake a five-year plan and convert the whole thing into a complete treatise on Verbal Behavior, instead of literary manifestations only (Skinner, 1979, p. 245).

Skinner was close to abandoning completely the traditional psychological approach to literature. As he said, I was obviously moving toward a book on verbal behavior as a whole. The psychology of literature was not the field I had embarked upon as a Junior Fellow . . . (Skinner, 1979, p. 248); that is, it was not the sort of analysis which he had started when challenged by Whitehead. He continued the teaching of a language course into the regular spring semester of 1941. But its description now differed considerably from the earlier one. This one covered, as Skinner stated, the nature and forms of verbal behavior; motivational and emotional influences in the emission of speech . . . (Skinner, 1979, p. 248). He was now moving the analysis into his theoretical framework.

It soon showed itself explicitly. He analyzed the process involved in the repeated guessing of alternatives (Skinner, 1942). In this article on repeated guessing, he objects indirectly to structuralism. He later phrases his objection explicitly, Behavior is discovered to have certain organizing principles which are then used to explain that behavior (Skinner, 1979, p. 251). What is interesting about the guessing article is the alternative explanation advanced by Skinner to the structuralist one. People were guessing patterns of coin tosses. For Skinner, guessing was simply a kind of verbal behavior distinguished by the fact that responses were not under the control of identifiable discriminative stimuli (Skinner, 1979, p. 251). Skinner then posits a type of contingency control over the guessing behavior. Instead of the reasons for the actions being embedded in the form of the actions themselves, it is the controls over the actions that give rise to the forms observed. And Skinner, for the first time in the reference section of a published paper (1942), lists his unpublished manuscript on Verbal Behavior.

The curve of Skinners professional career was then deflected. The United States entered World War II in December of 1941. Skinner threw himself into the war effort. Project Pigeon, a project to design missiles guided to their targets by pigeons, consumed his time from the Fall of 1942 to the Spring of 1944. It was, however, to his disappointment, discontinued. (At the time, radar was in development, but classified top-secret. Skinner was not informed of the reason for discontinuing Project Pigeon.) Nevertheless, the project demonstrated successful engineering applications of complex behavioral enterprises derived from his basic science formulations. Almost half a century later, that demonstration was echoed in the evidence-based teaching of language based on his formulation of verbal behavior. With both the immediate and the later engineering effects, he was fulfilling the stated aims of two of his scientist mentors, Bacon and Machthe proof of a valid and viable science was its useful outcomes.

As Project Pigeon wound down, in the summer of 1944 Skinner states that he was granted a sabbatical furlough to complete a manuscript on Verbal Behavior (Skinner, 1944). The new name of the work implies a much stronger commitment to his framework of analysis rather than to that of the traditional linguistic or psychological formulation. It is as if the central focus now emerged clearly into view for him. Soon he is teaching, not courses in the psychology of language but courses on verbal behavior, which he did in 1946 at Indiana University. We get snippets of what he was doing from third parties. In a letter from R. M. Elliot to E. G. Boring, Eliot writes,

Skinner went to work on his postponed Guggenheim project, the book on language, now announced to be two volumes in length. He made no effort to go elsewhere to finish the work, saying that he could just as well work it out in his own house and avoid the wartime congestion which he would find around the larger libraries of the country (Elliot, R.M. January 9, 1946).

This apparently refers back to the year Skinner set up a writing desk in the basement of his Minnesota home.

While Skinner was at Indiana (1945 to 1948), Fred Keller invited Skinner to give a summer course at Columbia University on verbal behavior. It was an important moment in Skinners attempt to achieve a coherent statement of his theoretical position on verbal behavior. It provided an opportunity to present an overview of his language analysis to a sympathetic yet knowledgeable audience; an audience that would provide him feedback and give him an opportunity to check on the firmness of the new foundations of the lingual relations he was investigating. It was the first complete public statement of his position. (The Columbia University Department of Psychology chairman wished to call the course The Psychology of Semantics and Skinner changed it to Psychological Interpretation of Verbal Behavior.) The material in Skinners course was taken from my courses on the Psychology of Language and the Psychology of Literature, as well as from the William James Lectures in preparation ( Skinner, 1979, p. 332). Skinner lectured from his prepared material, but did not provide written handouts. However, a young graduate student, Ralph Hefferline, managed to reproduce almost in toto what was said. Hefferline had developed a form of speedwriting that captured quite accurately the class lecture. From the Hefferline notes (hereinafter referred to as the Notes) we get a look at Skinners thinking on verbal behavior at the time, and as important, the changes that occurred between this first public presentation and the publication ten years later of Verbal Behavior. Across this gap, the Notes provide a bridge.

The Hefferline Notes

As pointed out, the Notes (1947) were based on a 5-week course, Psychology s247 Psychological Interpretation of Verbal Behavior, given by Skinner at Columbia University beginning in July of 1947. In the Columbia University summer bulletin he described the course as an analysis of basic processes in the behavior of the speaker and hearer. Logical, linguistic, and literary contributions are considered . . . (Skinner, Summer 1947). Ralph Hefferline later played an important role in the development of gestalt therapy and biofeedback technology (Knapp, 1986), but he also made substantial contributions to the experimental analysis of behavior. As Skinner explained, Ralph attended my lectures I gave on verbal behavior at Columbia in 1947 and since he was a very rapid stenographer he made a complete stenographic record. He then digested the material and published a long summary of my course (Skinner, personal correspondence, January 27, 1975).

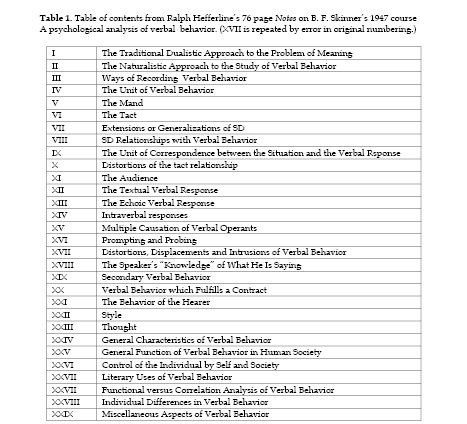

Skinner said that the Notes covered much more ground than my William James Lectures (Skinner, 1979, p. 332). Such an observation must be reconciled with the disparity in length. The William James Lectures are 176 single-spaced pages compared to the Notes of only 76 similarly spaced pages. Detailed in this context must mean something like level of discussion, or number of examples per page. The Notes do not contain summaries of the literature in any ordinary sense of that expression. There are no systematic citations or references. But there is a great density of examples and illustrations of verbal responses spread among 30 divisions of the 606 sequentially numbered unequal sections. These vary in length from a single sentence to paragraphs of several dozen sentences. Table 1 lists the titles of each of the divisions within the Notes.

The Notes open with a dismissal of the traditional manner of handling words and of their dualistic meaning, and calls instead for a naturalistic approach in which variables of which verbal behavior is a function are analyzed in terms of the conditions which lead to the emission of verbal behavior (Notes, p. 2). Skinner then introduces the now established categories of verbal relations such as mand, tact, and intraverbal. Thus, what one finds in the Notes is later directly reflected in the book Verbal Behavior (Skinner, 1957/1992). But there are a few differences in content between the brief Notes and the later volume. These warrant comment. Some concepts in the Notes are later renamed, some are taken up in other works by Skinner, and some appeared to be dropped completely. For example, in the Notes one large section (XIX) is titled Secondary Verbal Behavior and it deals in part with what becomes the autoclitic in Verbal Behavior. Another large section (XXVI) discusses Control of the Individual by Self and Society; here Skinner previews the self-control techniques elaborated in Science and Human Behavior (Skinner, 1953).

The topics dropped or changed may be the most interesting. In the Notes, Skinner used the expression hearer rather than the later listener. He explained the change in the Shaping of a Behaviorist (1976): In my early notes and in my course at Columbia I used hearer instead of listener. Russell used it in his review of The Meaning of Meaning in the Dial. It is a more comprehensive term . . . but it is hard to pronounce and listener was taking over (Skinner, 1976, p. 335). The concept of contract is introduced to cover circumstances in which there is a condition which requires behavior . We can call these contracts (Notes, p. 40). The contract says something about the behavior desired, but does not give us the behavior. For example, we simply want to be a writer but havent anything to say, or again we want to fill an awkward silence. There is no cue given as to what should be saidsimply the pressure for speech at any price (Notes, p. 40). A large section of the Notes (XXVIII) is devoted to Individual Differences in Verbal Behavior. This topic is completely dropped in Verbal Behavior. Nor does it appear in the William James Lectures. In fact, few discussions of individual differences occur anywhere in the corpus of Skinners works, and for an obvious reason: The concept of individual difference arises only when an organism is compared to other organisms on a characteristic or trait as measured by some metric. Intelligence Quotient is a classic example in the history of psychological practice. But individual differences do not arise in the experimental analysis of behavior since the on-going behavior of the individual organism is compared to its own behavioral baseline at an earlier or later time. (Skinners theory of behavior examines properties of behavior, not individuals.) When Skinner refers to the speaker and listener in Verbal Behavior he is referring to the actions of an individual organism in relation to controlling contingencies of reinforcement, punishment, discrimination, or induction, not in relation to trait qualities of other speakers or listeners. In a large section of Notes, Skinner explains, we could mention hundreds of differences among people with respect to verbal behavior, for which tests could be designed if wanted (Notes, p. 70). But he has just dismissed in the previous section (XXVII) a correlation analysis of verbal behavioradvocating, instead, his functional analysis. This distinction may have been at high strength in Skinners then current repertoire as one of his former students, John Carroll, had come under the influence of factor analysis, and hence, its analysis of behavior by multiple correlations of various tests that could be administered to individual speakers (Skinner, 1976, p. 213-214). Though through an amanuensis, the Notes (1947) provides the first written account of Skinners functional analysis of verbal behavior.

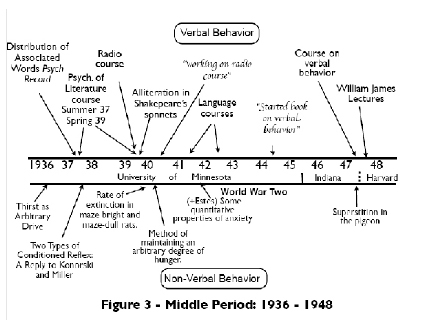

The Notes were soon superseded by the William James Lectures (Skinner, 1948). When a secondary account of Skinners analysis was published in an early textbook of the science of behavior (Keller & Schoenfeld, 1950), it was the William James Lectures that formed the foundation. In the early 1950s, Skinner would cite the availability of both the Notes and Lectures and the pressing need for a Natural Science 114 (his undergraduate course at Harvard) textbook as the reasons for postponing a final draft of Verbal Behavior (Skinner, 1983, p. 84). Today the value of the Notes resides in its record of Skinners analysis as that analysis made the transition from spoken form to its written representation as Verbal Behavior 10 years later in 1957. Figure 3 provides an overview of the work of his Middle Period.

Final Work: Late 1940s to 1950s

In a letter to Fred Keller in the spring of 1947, Skinner writes,

You may have seen an announcement of my assignment as William James lecturer at Harvard next fall. I have turned my laboratory over to my research assistants and an [sic] spending a number of hours each day at my desk working on what Im sure this time will be the final draft of Verbal Behavior. Boring has made a complete about-face and is fantastically chummy in all his letters.

Boring and Skinner had had a tense relationship when he was a graduate student and Boring was the department chair in the Department of Psychology. Skinner was a fervent advocate of behaviorism and Boring an ardent defender of structuralism. But that was all now in the past. To Borings credit, he recognized Skinners contribution to behavioral science. He took the lead in bringing Skinner back to Harvard as a faculty member and in arranging his appointment as the William James lecturer. It was Skinners grand opportunity to present his verbal behavior theory to one of the most important intellectual and academic communities in the country. He made the most of it, and made it the right set of circumstances to finish his book on Verbal Behavior.

The William James Lectures gave Skinner the opportunity and the incentive to once again plunge fully into the topic. As he later wrote in his autobiography, Shaping of a Behaviorist (1979), Obviously my topic would be verbal behavior. Except for one seminar I had done no further work on it since coming to Bloomington; (p. 324). The seminar to which he refers was the one he gave the prior summer at Columbia University. (Bloomington referred to his appointment to the Department of Psychology where he was now chairman.) I could plead the exigencies of a chairmanship, but I had undoubtedly digressed (Skinner, 1979, p. 324).

In his autobiography, Shaping of a Behaviorist (1979), Skinner describes the situation well:

Week by week I wrote my lectures, and Kitty Miller typed them. I delivered them on successive Friday afternoons. On the first day my audience was fairly large, and then it settled down to the size characteristic of a lecture series. Ivor Richards . . . not only came but read my lectures as I produced them. Bridgeman came and often had something to say afterward. . . . Edna Heidbreder came in from Wellesley and sent a good report to Mike Elliot.

More than a dozen years after Whiteheads challenge, I was presumably finishing a manuscript on verbal behavior, but I was taking it from a much larger version, and I wrote my lectures knowing that they would probably not be published as such. Nevertheless, they covered the main themes. When people spoke, wrote, or gestured, they were not expressing ideas or meanings or communicating information; they were behaving in ways determined by certain contingencies of reinforcement maintained by a verbal community. The contingencies had properties which were responsible for the special character of verbal behavior (p. 334).

In the fall of 1947, he again writes to Fred Keller,

The lectures are going fine. Garry is delighted. My audience has held up better than other WJ lecturers, and a few people (IARichards for xample [sic]) are highly enthusiastic. Im writing 10,000 words per week - and going to bed at 830 to keep it up. But Ive caught my second wind, and barring sickness, will finish on schedule. Another couple of months will be needed to get the Ms into shape.

Ten years would pass before he did get the Ms into shape.

Boring was delighted (he pushed for Skinners appointment at Harvard), but was factual about the lectures and their impact, and what may be done with them.

The first Lecture was fair but not too well planned, since the first part sounded as if it were read (it was) and the last was too hurried to be gotten in. But Fred is bright enough to learn, and he cut out twenty per cent of the second Lecture. Read slowly, and had his audience fully with him. There was very little loss from the first day to the second---perhaps 220 the first time and 210 the second. I. A. Richards came and George Parker, but mostly the unknown crew which goes to lectures in Cambridge. . . .

He is getting them typed and shaped for publication as he goes along, we have already talked to the Harvard Press which wants them. The scheme is to make a book of the ten Lectures which will run to about 80,000 words plus 20,000 words more of fine print inserted as running appendices (E. G. Boring, October 21, 1947).

Apparently the delay was not due to to a lack of opportunity to publish. Earlier there had been an interest by Appleton-Century-Crofts to publish a book by Skinner on verbal behavior. As Skinner (1979, p. 324) describes it, Elliott wrote that Dana Ferrin would be happy to be released from an implied agreement to publish a book that would have such a small readership. Now Harvard University pursued the opportunity. The title page of an original manuscript for the book on verbal behavior reads,

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by

B. F. Skinner

William James Lectures

Harvard University

1948

To be published by Harvard University Press.

Reproduced by permission of B. F. Skinner

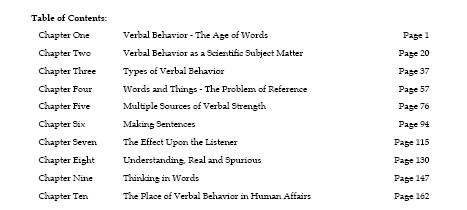

Currently, it is not known why this publication arrangement fell through. What is known is that the Table of Contents for the 1948 version of Verbal Behavior differs considerably from that of the final 1957 version. The 1948 Table of Contents reads as follows:

This 1948 Table of Contents differs considerably from the Table of Contents of the version published in Verbal Behavior in 1957.

It was not only the labeling of the chapters that differed, so did a good deal of the contents. For example, the 1948 version starts:

CHAPTER I: Verbal Behavior - The Age of Words

We call this the Atomic Age, and for good reason; but it is possible that we shall be remembered for our concern with the expansive rather than the exceeding small - for having aspired toward the heights rather than the depths - and that we are living in the Age of Words. Nothing is more characteristic of our times than the examination of linguistic processes. It is true, we cannot claim to have discovered wither the potency or the perfidy of wds, but we are perhaps the first to accept the consequences. Not only have we recognized the importance of language in human affairs; in some measure we have acted accordingly. This is true of every important field of human thought.

Whether it is to be atom or wd, the physical sciences have played the leading role. If the scientific materialism of the nineteenth century failed, it was not because any particular philosophy of nature was proved wrong, but because a question arose whether man could fully understand nature in terms of any philosophy whatsoever. The exigencies of scientific practice forced this issue into the open as a question of the validity of statements. Certain key words - among them, of course, the classical examples of space and time - had to be examined. This was the first sustained attack upon the problem of reference in the modern spirit. It is curious that it should have been made in the field which must have seemed least involved in linguistic difficulties (Skinner, 1948, p. 1).

But the very first sentence in the very first page in the 1957 published version of Verbal Behavior heralds a much different approach, Men act upon the world, and change it, and are changed in turn by the consequences of their actions (Skinner, 1957). In a first chapter now titled A Functional Analysis of Verbal Behavior, the first sentence announces Skinners own confidence in his theoretical position. It points directly to an analysis that focuses on contingencies of selection and that starts with the experimentally derived unit of the operant.

The spring of 1955 finds Skinner at Putney, Vermont, a small village in one of the smaller states of the United States in its northeastern corner. In the prior eight years, he had evidently been extensively revising his prior analysis of verbal behavior. A letter from D. H. Ferrinan editor at Appleton-Century-Crofts publishing houseto R. M. Elliot, dated April 5, 1948, gives the smallest of stray glimpses into his activity on verbal behavior, Last Friday Whitefield saw Keller and Schoenfeld and the latter told him that Skinner left with him for reading what Whitefield gathered was at least the first draft of his talked-of book on Verbal Behavior. If this is true I am rather surprised since I have not realized that Skinner was so actively at work on this project. It seems likely that what Skinner left was a copy of the William James Lectures. We have discovered no documentation of his efforts during these eight years beyond some hastily scribbled notes written in his personal notebook in August 1952 simply laying out plans to rework his verbal behavior book. These same notes are apparently reviewed in May 1953 and April 1954 where scrawls indicate a sort of inspection on progress. He took a sabbatical from Harvard that year in order to finish his manuscript on verbal behavior. In his personal notebook he writes on 5/13/55 in a page he titled Stock-taking:

Writing. Verbal Behavior nearly finished. Change chs 2 & 3, add 21 and 22 and last 3, omit epilogues, reduce Appendices & section in one chapter et voila!

The note is almost cryptic since it is written for himself. But the last two terms imply a sort of happy relief combined with a sense of exhilaration at having succeeded at an extraordinary challenge.

Conclusion

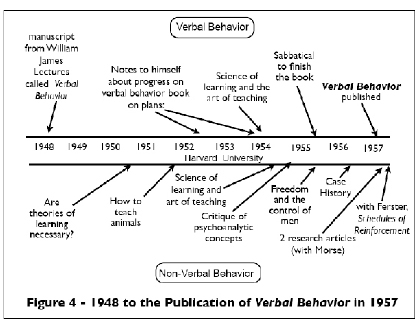

We place Figure 4, the overview of the final ten years before publication of Verbal Behavior, in the conclusion to emphasize once again the intertwining of Skinners work on verbal behavior with that work on behavior that was nonmediated. As pointed out earlier, the same year (1957) he finished Verbal Behavior, he also finished his and Fersters monumental work on contingency schedules (Schedules of Reinforcement). Skinner engaged in and published other experimental work, such as that with Morse (Morse & Skinner, 1957a, 1957b). Furthermore, within his theoretical framework he considered a number of cultural and professional issues, for example, Freedom and the control of men (Skinner, 1955-1956) and Critique of psychoanalytic concepts (Skinner, 1954). From within his theory of behavior, he further extended its engineering applications started during World War II into the area of animal training How to teach animals (Skinner, 1959/1999), and into the social institution of educationThe science of learning and the art of teaching (Skinner, 1959/1999). The first, animal training, exploded in an extraordinary way into every arena of animal care and training, from zoo husbandry to commercial enterprises. The second, the extension to education, specifically started as programmed instruction. But its principles and features have now become part of all mainstream education so that those programmed instruction origins are no longer even recognized. Programmed instruction directly derived from Skinners analysis of verbal behavior, as does most of the effective language training with autistic children.

The summary above makes clear and drives home the point, once again, that Skinners analysis of mediated behaviorverbal behavior whose forms are shaped under particular controls by a cultural communityoperated within the theoretical framework of his theory of behavior; a theory that also encompassed his work with nonmediated behavior. Both operated under the same principles. Skinner himself makes this point not once but twice in the ending pages on his book on verbal behavior.

There is nothing exclusively or essentially verbal in the material analyzed in this book. It is all part of a broader field (Skinner, 1957, p. 452).

Originally it appeared that an entirely separate formulation would be required, but, as time went on, and as concurrent work in the field of general behavior proved more successful, it was possible to approach a common formulation (pp. 454-455).

The history of Skinners work on verbal behavior is the history of all his work within the framework of his theory of behavior.

Bibliographical References

Boring, E. G. (October 21, 1947). Letter to R. M. Elliot. Harvard University Archives.

Crozier, W. J. ( June 3, 1931). Letter to B. F. Skinner. Harvard University Archives.

Crozier, W. J. ( June 4, 1931). Letter to B. F. Skinner. Harvard University Archives. Quoted in Vargas, E. A. 1995, Prologue, perspectives, and prospects of behaviorology. Behaviorology, 3, p. 108-109.

Elliot, R. M. ( January 9, 1946). Letter to E. G. Boring. Harvard University Archives.

Ferrin, D. H. (April 15, 1948). Letter to R. M. Elliot. Harvard University Archives.

Ferster, C. and Skinner, B. F. (1957/1997). Schedules of Reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Holtan, G. (1973/rev. ed. 1988). Thematic origins of scientific thought: Kepler to Einstein. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Keller, F. S. & Schoenfeld, W. N. (1950/1995). Principles of psychology: A systematic text in the science of behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation.

Knapp, T. J. (1986). Ralph F. Hefferline: The Gestalt therapist among the Skinnerians or the Skinnerian among the Gestalt therapists? Journal of the History of the Behavioral Science, 22, 49-60.

Morse, W. H. and Skinner, B. F. (1957a). A second type of superstition in the pigeon. The American Journal of Psychology, 70, 308-311.

Morse, W. H. and Skinner, B. F. (1957b). Concurrent activity under fixed-interval reinforcement. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology, 30, 279-283.

Richards, R. J. (1987). Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1930). The concept of the reflex in the description of behavior. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA.

Skinner, B. F. (October 2, 1931). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. Cambridge, MA.

Skinner, B. F. (July 2, 1934). Letter to F. S. Keller . Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (1935a). Two types of conditioned reflex and a pseudo type. Journal of General Psychology, 12, 66-77.

Skinner, B. F. (January 18, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (March 15, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (June 21, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (September 25, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. December 6, 1936). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (1936). The verbal summator and a method for the study of latent speech. Journal of Psychology, 2, 71-107.

Skinner, B. F. (1937). Two types of conditioned reflex: A reply to Konorski and Miller. Journal of General Psychology, 16, 272-279.

Skinner, B. F. (April 19, 1937). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (1938/1991). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts /Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation.

Skinner, B. F. (November 14, 1938). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (1939). The alliteration in Shakespeares sonnets: A study in literary behavior. Psychological Record, 3, 186-192.

Skinner, B. F. (1942). The process involved in the repeated guessing of alternatives. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 30, 495-503.

Skinner, B. F. (1944). Handwritten chronology written in preparation for his autobiography. Personal collection.

Skinner, B. F. (January 7, 1947). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (Summer, 1947). Hefferline Notes. Transcription of Skinners course on verbal behavior at Columbia University, New York.

Skinner, B. F. (Fall, 1947-no month or day indicated). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Verbal Behavior. Unpublished manuscript. Personal Collection.

Skinner, B. F. (1950). Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review, 57, 193-216.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1954). A critique of psychoanalytic concepts. Scientific Monthly, 79, 300-305.

Skinner, B. F. (1955-56). Freedom and the control of men. American Scholar, 25, 47-65.

Skinner, B. F. (1957/1992). Verbal Behavior. New York; Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation /Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation.Skinner, B. F. (1957/1997). Schedules of Reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation.

Skinner, B. F. (January 27, 1975). Letter to T. J. Knapp. Personal collection.

Skinner, B. F. (1999) How to teach animals. In Cumulative Record, Definitive Edition. B. F. Skinner Foundation. 605-612. Originally published in 1959.

Skinner, B. F. (1959/1999). The science of learning and the art of teaching. In Cumulative Record, Definitive Edition. 179-191.

Skinner, B. F. (1969). Contingencies of Reinforcement; a theoretical analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York.

Skinner, B. F. (1979). The Shaping of a Behaviorist. New York; Alfred A. Knopf.

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by consequences. Science, 213, 501-504.

Stott, R. (2003). Darwin and the Barnacle. New York; W. W. Norton & Co.

Vargas, E. A. (1992). Introduction II to Verbal Behavior. Cambridge, MA: B. F. Skinner Foundation. pp. xiii-xv.

Vargas, E. A. (1995). Prologue, perspectives, and prospects of behaviorology. Behaviorology, 3, pp. 107-120.

Vargas, E. A. (1996). Explanatory frameworks and the thema of agency. Behaviorology, 4, pp. 30-42.

Wallace, A. R. (1869/1922). The Malay Archipelago. London; Macmillan & Co.

Recebido em:11/12/2007

Primeira decisão editorial em: 11/21/2007

Versão final em: 11/26/2007

Aceito em: 04/16/2008

1Contributions of the authors were in the order given. We particularly appreciate a review of the manuscript given by Dr. Jerome Ulman.

2Ph.D. Vice-President of B. F. Skinner Foundation. E-mail: eavargas@bfskinnerfoundation.org

3Ph.D. B. F. Skinner Foundation.

4Ph.D. University of Nevada.

5 A similar balance of intellectual labor continued throughout his scientific career. For Skinner, theory was as important as laboratory work. He even wrote an article (Skinner, 1950), Are Theories of Learning Necessary, to which he gives a firm yes if of the right sort. He emphasized that theories must be couched in the dimensional framework of the sciences subject matter so that, for example, behavioral phenomena should not be interpreted using physicalistic explanations. Any range of behavioral phenomena may be accommodated within a contingency selection framework, from neurophysiological events to the lingual activity of a culture. Though the thematic and empirical content of his theory is implicit in his many writings, Skinner makes explicit features of his theory in articles and books such as Selection by Consequences (1981) and Contingencies of Reinforcement, A Theoretical Analysis (1969).

6The same phenomenon referred to animal movement.

7 As the reader may note, in the analysis of lingual behavior other redundant agencies continue to be promoted such as a self or a speaker or a more subtle equivalent construct like a sentence generating structure. Skinners use of the term speaker is that of a location. It should not be construed as an originating force.

8Rene Descartes (1596-1650)) did it by separating mind from matter. He then further asserted that the quality of mind was what separated humans from animals, the latter being by and large nothing more than complex machines. Descartes agency of mind (and its accompanying dualism) constitutes the core of much current behavioral science especially when it comes to matters of language. It still resonates in the present day theory of mind. Alfred R. Wallace (1823-1913), co-originator of the natural selection process that drives evolution, agreed with Darwin that there was a continuum between humans and other animal life except when it came to mans mind. The reader of this essay no doubt knows of Descartes but for those encountering him for the first time, probably the best place to start is with his Discourse on the Method. Wallace, like Darwin, has the happy accident of being a clear and interesting read. Though place names must be changed, The Malay Archipelago (1869/1922) still appeals for the reader attracted to natural history. For further information on the split between Darwin and Wallace on the continuity issue of brain and behavior, the interested reader can start with Richards, R. J. (1987). For what these issues imply to the behavioral sciences see Vargas, E. A. (1996).

9A. N. Whitehead (1861-1947) was a noted mathematician and philosopher who occasionally had dinner with Harvard Universitys Society of Fellows. He coauthored, with Bertrand Russell, Principia Mathematica, an attempt to lay out the foundations of mathematics through symbolic logic. In his later years (his sixties), he came to teach at Harvard University. His acknowledgment of the merits of behaviorism appears as quite a concession to the young Skinner as Whiteheads process philosophy would seem to be at odds with it.

10Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) was a biogeographer and the foremost botanist of his day. As Curator of Kew Gardens, he was a well known and important defender of Darwins views.

11 William John Crozier (1892-1955) was head of the Physiology Laboratory at Harvard University in which Skinner had his fellowship. Crozier was the most powerful influence on Skinner in his early years as a graduate student. For further detail, see Skinner (1979) and Vargas (1995).

Boring, E. G. (October 21, 1947). Letter to R. M. Elliot. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Crozier, W. J. ( June 3, 1931). Letter to B. F. Skinner. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Crozier, W. J. ( June 4, 1931). Letter to B. F. Skinner. Harvard University Archives. Quoted in Vargas, E. A. 1995, Prologue, perspectives, and prospects of behaviorology. Behaviorology, 3, p. 108-109. [ Links ]

Elliot, R. M. ( January 9, 1946). Letter to E. G. Boring. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Ferrin, D. H. (April 15, 1948). Letter to R. M. Elliot. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Ferster, C. and Skinner, B. F. (1957/1997). Schedules of Reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [ Links ]

Holtan, G. (1973/rev. ed. 1988). Thematic origins of scientific thought: Kepler to Einstein. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Keller, F. S. & Schoenfeld, W. N. (1950/1995). Principles of psychology: A systematic text in the science of behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1986). Ralph F. Hefferline: The Gestalt therapist among the Skinnerians or the Skinnerian among the Gestalt therapists? Journal of the History of the Behavioral Science, 22, 49-60. [ Links ]

Morse, W. H. and Skinner, B. F. (1957a). A second type of superstition in the pigeon. The American Journal of Psychology, 70, 308-311. [ Links ]

Morse, W. H. and Skinner, B. F. (1957b). Concurrent activity under fixed-interval reinforcement. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology, 30, 279-283. [ Links ]

Richards, R. J. (1987). Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1930). The concept of the reflex in the description of behavior. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (October 2, 1931). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (July 2, 1934). Letter to F. S. Keller . Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1935a). Two types of conditioned reflex and a pseudo type. Journal of General Psychology, 12, 66-77. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (January 18, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (March 15, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (June 21, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (September 25, 1935). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. December 6, 1936). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1936). The verbal summator and a method for the study of latent speech. Journal of Psychology, 2, 71-107. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1937). Two types of conditioned reflex: A reply to Konorski and Miller. Journal of General Psychology, 16, 272-279. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (April 19, 1937). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1938/1991). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts /Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (November 14, 1938). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1939). The alliteration in Shakespeares sonnets: A study in literary behavior. Psychological Record, 3, 186-192. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1942). The process involved in the repeated guessing of alternatives. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 30, 495-503. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1944). Handwritten chronology written in preparation for his autobiography. Personal collection. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (January 7, 1947). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (Summer, 1947). Hefferline Notes. Transcription of Skinners course on verbal behavior at Columbia University, New York. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (Fall, 1947-no month or day indicated). Letter to F. S. Keller. Harvard University Archives. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Verbal Behavior. Unpublished manuscript. Personal Collection. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1950). Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review, 57, 193-216. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1954). A critique of psychoanalytic concepts. Scientific Monthly, 79, 300-305. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1955-56). Freedom and the control of men. American Scholar, 25, 47-65. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1957/1992). Verbal Behavior. New York; Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation /Cambridge, MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1957/1997). Schedules of Reinforcement: New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts/Cambridge MA; B. F. Skinner Foundation. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (January 27, 1975). Letter to T. J. Knapp. Personal collection. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1999) How to teach animals. In Cumulative Record, Definitive Edition. B. F. Skinner Foundation. 605-612. Originally published in 1959. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1959/1999). The science of learning and the art of teaching. In Cumulative Record, Definitive Edition. 179-191. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1969). Contingencies of Reinforcement; a theoretical analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1979). The Shaping of a Behaviorist. New York; Alfred A. Knopf. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1981). Selection by consequences. Science, 213, 501-504. [ Links ]

Stott, R. (2003). Darwin and the Barnacle. New York; W. W. Norton & Co. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1992). Introduction II to Verbal Behavior. Cambridge, MA: B. F. Skinner Foundation. pp. xiii-xv. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1995). Prologue, perspectives, and prospects of behaviorology. Behaviorology, 3, pp. 107-120. [ Links ]

Vargas, E. A. (1996). Explanatory frameworks and the thema of agency. Behaviorology, 4, pp. 30-42. [ Links ]

Wallace, A. R. (1869/1922). The Malay Archipelago. London; Macmillan & Co. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em