Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva

versão impressa ISSN 1517-5545

Rev. bras. ter. comport. cogn. vol.9 no.2 São Paulo dez. 2007

ARTICLES

Skinner verbal behavior: functions of quoting in Verbal Behavior1

Elizeu Borloti2

Federal University of Espírito Santo

ABSTRACT

Verbal Behavior (VB) was Skinners most important work. Generic self-analyses of the behavior registered on VB appears in its final parts and in other works from the author. This paper describes the functions of two specific subclasses of quoting episodes with another authors text transcription included by Skinner in VB. It deals with a historical research of the VB as the record of Skinners verbal behavior. From the general description of quoting with transcription, a functional analysis of two distinct subclasses was carried out by their autoclitic frame, according to the behavioral hermeneutics: a method that instructs a description of the controls over interpreting. The formal-functional variations of both subclasses are informed: accurate verbal stimuli evoked the argumentative quoting (uttered with descriptive autoclitics) and the inaccurate stimuli evoked the counter-argumentative ones (uttered with manipulative and/or negation autoclitics). Despite the difficulty in discriminating all the controls on the interpretation, this paper successfully shows the functional consistency of some the devices of persuasion in the Skinnerian rhetoric.

Keywords: Functional analysis of quoting, History of psychology, Verbal behaviour, Autoclitic.

Verbal Behavior (VB, Skinner, 1957) is, according to Skinner (1978), his most important work. Dougher (1993) regarded it as the most comprehensive and ambitious attempt at a contextualistic analysis of verbal behavior (p. 216). In general, the book presents the records of what Skinner did while writing it: I believe that my behavior in writing Verbal Behavior, for example, was precisely the sort of behavior the book discusses (Skinner, 1967/1970, p. 16).

Perhaps because of such importance, much has been said about VB in critical reviews (Bradbent, 1959; Chomsky, 1959; Dulaney, 1959; Farrell, 1960; Gray, 1958; Jenkins, 1959; Krasner, 1958; Mahl, 1958; Morris, 1958; Neimark, 1960; Osgood, 1958; Peel, 1960; Solley, 1958; Tikhomirov, 1959; Zehrer, 1959). The discussions specifically concern: chapter 18 (Logical and Scientific Verbal Behavior, Schnaitter, 1980), the autoclitics (Borloti, 2004; Catania, 1980), the historical conditions of the writing of the book and the extension of its analyses (Day, 1980; Knapp, 1980), problems in specific sections (Place, 1981a, 1981b, 1982, 1983), misunderstandings of the works object of analysis (Lee, 1984), the works influence on empirical researches (McPherson, Bonem, Green, & Orborne, 1984), the concept of tact (Place, 1985), errors and omissions in the bibliographical references (Morris & Schneider, 1986), the works influence on linguistics (Andresen, 1990), the opinions of the works reviewers (Justi & Araujo, 2004; Knapp, 1992; McCorquaodale, 1970) and the works contemporary status(Abib, 1994). Nevertheless, the record of specific responses in VB (specially quoting) was not analysed in an analytic-behavioral framework (Borloti, 2003).

Morris and Schineider (1986) even provided a list of bibliographical references drawn in VB and said it could convey some initial suggestions about the literary, scientific, and philosophical material that may have acted as controlling variables to shape and maintain Skinners analysis of verbal behavior as a whole (p. 40). However, this list is incomplete, since it presents only the works cited on the footnotes of some pages (formal quotings) and the ones not cited, whose authors names appear on the index though (informal quotings).

Even the information given by Skinner about the controls for writing it seem to be incipient: on page 11, he says that during the writing no effort has been made to survey the relevant literature(Skinner, 1957, p. 11). On page 454, he said that the search for sources of verbal stimuli for writing VB was a process which had begun in remote times, when he was still an undergraduate at the school of Language and Literature of Hamilton College (Coleman, 1985). Perhaps due to the lack of such effort, the description he did about these sources is generic:

To begin with, I exposed myself to a great deal of materials in the field of verbal behavior. This was the result of a growing interest in the field, which followed from other circumstances too remote to affect the present issue. Hundreds of the books and articles which I read were not a direct exposure to the subject matter of verbal behavior itself, but they generate verbal with respect to it which showed an enormous variety and a fabulous inconsistency. I have also read books, not for what they said about verbal behavior, but as records of verbal behavior (Skinner, 1957, p. 454).

In order to present specific functional elements added to this general description, the aim of this paper is to describe the function of two subclasses of quoting episodes (tacted as argumentative and counter-argumentative quoting) in which Skinner rewrote sentences removed from the texts written by authors he had cited. Thus, the first section describes the method applied for the achievement of such aim. The second one presents the result of such effort and the functional classification of these subclasses of quoting (after the description of their forms). Based on the data from VB and its impact on the researcher as a reader, each analysed class was tacted from the drawing of its fundamental autoclitic frame.

According to Borloti, Iglesias, Dalvi and Silva (2008), the autoclitics are processes involved in the verbal style, which interest students of Rhetoric. For this reason, there was an option for the functional description (the one which contemplates quoting) of part of Skinners discourse based on the analysis of such unities, since they depend on basic operants described in VB. Therefore, such unities account for the special arrangements Skinner made in these operants during their autoedition initiated in the thirties (Borloti, 2003).

In its functions, the autoclitics uttered by Skinner altered the effects of such operants on the reader of the book (Catania, 1998; Skinner, 1957) by 1) informing about the operant types written in the context of quoting, by 2) describing the strength of the utterances of such operants in this context, by 3) describing the relation between such operants and the operants described by the cited author, by 4) describing Skinners emotional and motivational conditions when writing the book, by 5) foreseeing that what the reader will read should produce the same effect of what he has just read, by 6) qualifying the operants uttered by the author in order to change the direction or intensity of the readers behavior, by 7) instructing the reader to arrange and relate their reactions to what the author wrote (as Skinner judged more appropriate), by 8) indicating either Skinners writing property or the circumstances responsible for such property, by 9) instructing the reader to draw a reading based on specific properties and by 10) impelling the reader to behave in a particular way, according to the relations between the basic operants written by Skinner in the context of quoting.

The relevance of this kind of analysis may rely on some of its properties. As previously stated, the aim of the analysis is an important book for Behavior Analysis: a book whose content is regarded as being difficult by the own analists (Day, 1980) and erudite by some critics (Solley, 1958; Neimark, 1960). Moreover, this kind of analysis is rare in Behaviour Analysis: since VB was published in 1957, a long time has passed for researchers to use the functional categories there described (McPherson et al., 1984), specially the autoclitic category and its subtypes, which are deemed difficult given the multiple causation (Borloti, 2004), which makes the stimulus control over them rather complex (Skinner, 1957, p. 147).

Also, this analysis may allow for an outlook on the scope of radical behaviorism regarding discourse analysis, a method which is widely used in qualitative research in the field of psychology and social sciences. The analysis can be considered a behavioral strategy for the so-called discourse (Borloti et al., 2008) and may, therefore, contribute to other historiographic and social researches.

Under the focus of Behavior Analysis, the written historical document is a product of its authors verbal behavior. Thus, two behavioral premises about history are adopted so as to make this paper relevant: 1) the historical investigation read neither with past events nor with the relationship between such events and its documentation; it deals with the researchers interaction with the verbal records of such events so as to tell a story (Parrot & Hake, 1983, p. 123); 2) the account of such story is the general effect which the verbal product has on the researchers verbal repertory. That is, a story emerges when the researcher describes such effect (Skinner, 1957, p. 452).

This paper also contributes to a method of traditional study called quotation analysis, which was here treated differently. As a research method in the field of history of science, the quotation analysis developed when started to deem a quote as a variable dependent on references, authors and knowledge subjects. Garfield (1979) suggested that the quoting analysis would be useful as a method because it would promote a functional view of the accumulated feature of scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, Skinner said that while he was writing VB, he did not want to cover all the relevant accumulated literature on verbal phenomenon, since he reckoned it traditional. Yet he inevitably cited authors and works he deemed relevant for other reasons. Thus, the pragmatism of this analysis relies on the description of the function of quotations related both to Skinners accessibility to a certain author (McPherson et al. , 1984) and this authors visibility in the writing social context of VB (Smith, 1981).

In general terms, this paper describes a path to functionally analyze a text (fiction or non-fiction) or a discourse, which was a challenge already recognized by behavior analysts in the late nineties (Knapp, 1998; Leigland, 1998; Mabry, 1998; Michael, 1998; Schlinger, 1998; Sundberg, 1998).

Methodology

Verbal Behavior was the verbal record (or written document) which provided the verbal data for this study and was considered a primary document/source. Other secondary sources were used: Skinners autobiographies (1967/1970; 1979), the text written by him (1948) for the William James Conferences (which was, in fact, VBs written outline) and the summaries of the cited works in VB.

The behavior of interest or, saying properly, the data is quoting authors and works throughout VB, focused by its form and basic function. Quoting was chosen because many citations, specially the literary ones, turns VB into an erudite scientific work. Solley (1958) for instance, found it eccentric and Neimark (1960) detected in its pages a strong sign of intelectual snob.

Procedural Stages

Stage 1: the quoting episodes were discriminated during the reading of VB under the verbal control of its description: any form of reference to author(s), work(s), excerpt(s), word(s) or character(s) with the aim of referring or transcribing a text (which might be quotes or writings) of such author(s) in support to Skinners affirmations in VB. This definition, thus, allowed the listing of other forms of quoting disregarded by Morris and Schneider (1986). In the repeated readings, the definition controlled the emission of quotings in a specific context. Each episode was specified with information (cited work and year of publication, cited author, contextual information about author and work, nationality and authors field of knowledge) contained in: a) the world wide web, b) Harvard University and B.F Skinner Foundations libraries, c) the prefaces of cited works and d) Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of Literature (1995).

Stage 2: with the listing of 488 quoting episodes, the observation of their properties allowed them to be grouped in two main categories: quoting with transcription (responses of quoting which produced typographic record in VB with the transcription of a group of words written by the author cited by Skinner) and quoting without transcription (responses of quoting whose typographic record is a continuous sequence of written operants emitted by Skinner). The great category quoting with transcription was chosen for the functional analysis, since it shows more clearly the process of Skinners verbal behavior reinforcement in the thesis dialogue he supports throughout the pages of VB.

Stage 3: afterwards, the researcher repeatedly read all the episodes from the quoting with transcription under the instructive control of behavioral hermeneutics (Dougher, 1993, p. 216-217), which is an interpretative technique to instruct the four steps of an analytical action: 1) recording of each episode and previously written events which appear to be functionally related to the episode, 2) the analysis of the function of registering of such previous events and refinement of the already made listings, 3) selection of the listed verbal relations and their grouping in functional subclasses and 4) description of the experience of being controlled by the document (VB) and accounting for what and why it was selected.

In step 1, the researcher recorded in a chart the episodes and its possible precedents. The readings which allowed this were made from broader segments of verbal recordings initiated and finished in close or distant points in the transcription, i.e paragraphs, subtitles and, at times, titles in VB.

In step 2, in this same chart, the researcher took notes of textual stimuli from other sources of data (previously described) which affected the listing of the precedents.

The segment in step 3 allowed for the listing of four functional subclasses from quoting with transcription: argumentative, counter-argumentative, exemplifying and analytical. The description thus generated is the analysis of the function of subclasses, which were considered as modalities of Skinners writing verbal style. The researchers verbal behavior under the control of the fundamental autoclitic unities indicated functional subclasses in this style. They were tacted according to the procedure described by Borloti (2004), who instructs on how to distinguish them by basing on their effects on the reader (as previously listed).

Step 4 consists of a functional analysis of the researchers verbal behavior, since it intended to inform about the effects of VB on interpretation in each previous step. In fact, hermeneutics involves a description of the multiple causations sources in interpreting, which come from various used sources. It produces a combination of effects in the researchers verbal repertoire.

Also, during the confirmation of the listings made, the procedure of inferences of relevant controlled variables of static verbal records was used. Such procedure instructed the variation in the modulation of pitch, energy and speed of the readings for the verbal record, as suggested by Skinner (1957: 26). A description of the researchers covert analytic verbal performance can be done through the description of some questions he made to himself: Here Skinner seemed boastful to me. Why?, Skinners affirmation appears to be ironic. Why?, Which response of mine is he trying to anticipate? are samples of such questions.

Finally, all the described discriminations were corroborated by more than one reader.

All the verbal material read and cited with transcription during the process of composition of VB affected Skinner in the emission of four subclasses of quoting with transcription: argumentative, counter-argumentative, exemplifying and analytical quotings. The next section presents and discusses the results of the functional analysis of the argumentative and counter-argumentative quotings because of its importance in the reinforcement of Skinners arguments and/or in the opposition he draws between the new functional approach and those deemed traditional (To access the complete analysis of all classes and subclasses, see Borloti, 2003).

Results and Discussion

From the 488 quotations in VB, 147 fit the large category quoting with transcription. The important autoclitic functions which followed and competed with quoting with transcription indicate a type of specific control over the writing of VB.

A reading of the episodes from this category allows for the discrimination of certain functional consistencies in the act of quoting in VB, despite Skinners claim (1957) that his writing may have been emitted with a fabulous inconsitency (p.454). Even the mostly classic literary works known by him and supposedly by a layperson were used, either as an illustration of the contents or as a record to be analysed. According to Skinners intention, this record would expand the influence of his verbal behavior, which would be emitted with the expressed aim to enhance the individual verbal repertoire (p. 455) of his readers. Once the justifications for the use of quotings were considered (McPherson et al. , 1984), Skinner may have chosen either the accessible materials or the ones produced by authors who were visible in discussions about language before the publication of VB in 1957. However, other criteria may have been suggested by particular properties of each product: some verbal products were more convincing than others. When they were convincing, some would compose the subclass argumentative quoting and would be emitted with an autoclitic frame as (someone)said: . When they were not, they would compose the subclass counter-argumentative quoting, which was emitted with the frame (someone) said that , but . (The transcribed excerpt is placed between parenthesis in the frames and the underlined parts indicate its fundamental autoclitic unit). In the following sections are the discussions on the functional properties of these two subclasses.

1. Argumentative Quoting

(...as (someone) said: ...)

Considering Skinners definition of belief in the writer (1957: 159-160), some transcribed texts in VB are verbal stimuli which, in his evaluation (inferred from the form and the consequence of his writing), were the effect of a relatively accurate stimulus control and which, due to this fact, affected the actions generated by the verbal phenomena analysed during the writing of VB. This is the reason why they reinforced the arguing. In a functional categorization, these transcriptions are part of the subclass argumentative quoting (AQ): answers in which part of the product is a transcription of the verbal product from an author credited by Skinner. In this sense, AQs were emitted to enhance a particular repertoire during the readers mediation, in the same direction of the enhancement promoted by Skinners arguing registered at some other point in VB.

As an example, one has to consider an excerpt from Charles Dickens Letter to Dr. Stone on page 393 in VB. Skinners argument that the writers use to attribute their productions to another person (when he discusses the explanations given during the writing, which does not receive any feedback in the moment of emission) is complemented by Dickens argument: Language has a great part in dreams. I think, on waking, the head is usually full of words .

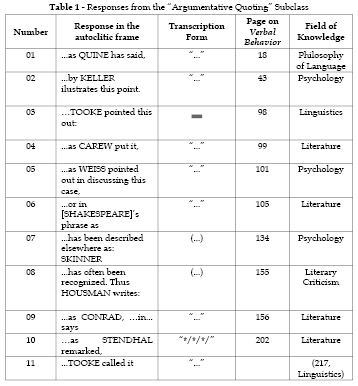

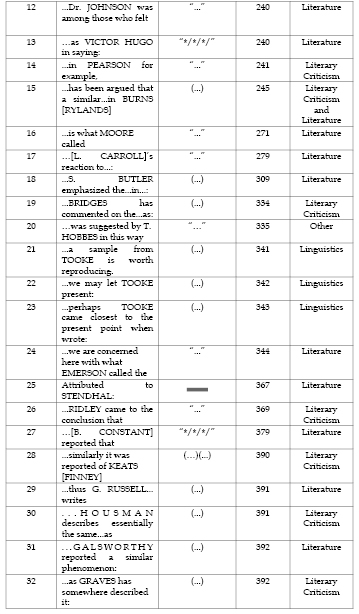

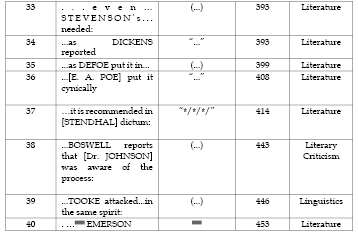

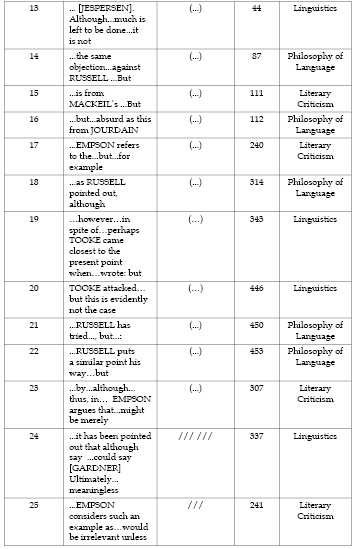

Forty episodes were listed in the AQ category. The topography of the answers varied according to the following: 17 episodes of another authors text transcription appear between quotation marks, as shown in Table 1: ; 17 episodes of transcription highlighted in the text, as shown with ( ); 4 episodes of transcription between commas, in italics and in French: */*/*/; 1 episode of transcription with quotation marks and footnotes: ... ;1 episode of transcription in italics as an epigraph (the motto of the first personal epilogue: ///. Table 1 shows the quotings, the page where they are located in VB, and the field of knowledge to which they belong. The names of the authors appear in capital letters. They may also appear in brackets when the utterance belongs to one of their fictional characters, to the literary critic who has commented on their excerpts or to an author not cited in VB.

Considering all the 40 responses in the argumentative subclass, Skinner used products of verbal behavior from literary authors to support his point. In 9 of them he used texts from literary critics (Housman, Finney, Pearson, Pater, Bridges, Ridley, Graves e Boswell) and in 6 he used Tookes The Diversions of Purley. Three cited literary criticism books were published in the 1930s : The Name and the Nature of Poertry (1933), Keats Craftsmanship: a Study in Poetic Development (1933) and The Evolution of Keats Poetry (1936).

Quoting Quine (AQ 1) was reinforced by the similarity between some of the philosophers working properties and Skinners considerations on logic behavior analysis. In a passage of his autobiography, Skinner (1983) reconfirmed this similarity with the affirmation that [Quine] reached close to what I wanted (p. 395).

The quoting of psychologist A. P. Weiss is justified by the history of behaviorism in the study of language. Powell and Still (1979) included him in the list of behaviorists who preceded Skinner in the study of verbal processes. In the authors own words, to quote him in an argumentative dialogue is justified by the type of a classificatory scheme proposed [by Weiss] in terms of behavioral features of the speech categories, which suggests the scheme proposed by Skinner (1957) (Powell & Still, 1979, p. 78).

Table 1 shows the scope of the written form in the argumentative function in the writing of VB. The textual structures displayed on the table as the original in English have many written forms of autoclitic processes typical of the concordance. Therefore, it is possible to affirm that the AQs basically consisted of a response starting with as, of grammatical relations in the past tense, of articles, pronouns, adverbs and, according to Catania (1980), of responding groups from which no part can be designated as a unitary autoclitic response (p. 176). In this sense, the consequence to the various responses was the same, therefore constituting this subclass.

Once the response as is also reemphasised with properties of comparison or similarity by the English linguistic community, the reinforcement of such response in VBs argumentative context becomes clear. Same, similar and all their desinencies were strengthened under these same conditions, and this justifies their emission in this subclass. The connection between autoclitics is perceived in the emission of quantifiers (the present point, the same, a similar phenomenon, the process, the same spirit, this point, this case), tact unities of the similarity properties among the properties of Skinners behavior and the properties of the transcription and, therefore, reinforcing their discrimination.

Skinner also emitted some unities that indicated the discrimination of his own verbal behavior, which were controlled by properties of the transcribed text in some AQs shown in Table 1. Thus, the descriptive autoclitics cynically, similarly e essencially indicate the possible authors condition while transcribing the texts of Allan Poe, Finney and Housman, respectively. These unities modified (and continue to modify) all the excerpts concerning the transcription and, due to this, indicate the motivational or emotional conditions in which each of these episodes could have been emitted. This function may have acted (as it still does today) when Skinner cited E.A. Poe after arguing about the forms which those who write with the resources of classic rhetoric found to make use of certain practices in the generation of a new behavior. Here are Skinners probable motivational conditions (1957): Edgar Allan Poes M. Dupin put it cynically: The mass of the people regard as profound only him who suggests pungent contradictions of the general idea. (p. 408)

The autoclitics which accompanied the transcriptions of poet Emersons passages and the passages from etimologist Tooke also have the same function of the group shown above, in the sense that they are discriminations that Skinner made of his own behaviour, and which were evoked according to the text properties of the cited authors. However, these autoclitics are of a different type.

In the case of Emerson, Skinner begins chapter 14 (Composition and Its Effects) by quoting him at the same time he admitted the existence of relations between properties about which he was writing in that chapter and properties described in Emersons transcription: We are concerned here with what Emerson called the shuffing, sorting, ligature and cartilage of words. The autoclitic we are concerned with indicated a discrimination of properties of Skinners verbal behaviour controlled by transcription properties and, because of that, enhanced Skinners arguing emitted right after: The speaker not only emits verbal responses appropriate to a situation or to his own condition, he clarifies, arranges, and manipulates his behavior. .

Other two descriptives also indicated the tact from properties of similarity between Skinner and Tookes behaviors verbal products and were particularly used to indicate Skinners motivational and emotional conditions to cite Tookes work and consider it as being extraordinary (1957: 340). We may let indicated a polite consent for Tooke to speak on behalf of Skinner, and is worth reproducing emitted on the footnotes of page 341 from VB indicated the acknowledgement and importance of Tookes book in the analysis of the autoclitics in VB.

In one of the atypical cases of AQs (in the first personal epilogue), Skinner followed his friend Hendersons suggestion and cited a line of Emersons poem Brahma as a motto for VB When me they fly, I am the wings . A possible interpretation of this poetic line is evoked from the reading of the title immediately above the epigraph The Validity of the Authors Verbal Behavior and from the transcription of Russells remarks on the false aura of objectivity in the comments made by behaviorists. Skinner deemed Russells critique as legitimate and raised some questions not accounted by him. The crucial question was the validity of observations about the world. Then, Skinner wrote that VB offers a case concerning this question, which is this: the book is a description of certain phenomena of the world and the validity of such description should be judged by their sentences, which is describing contingencies still not described by readers. And those readers should find a correspondence between the real world and what is specified in the book.

Thus, Skinner engaged in the description of what he had been doing while writing and what he expected from the readers of VB (also while writing), as an effect of his behaviour. In that moment he assumed he was not neutral. That is, if one considers Emersons verse, Skinners VB consists of verbal descriptions of verbal phenomena. The pronoun they from Emersons lines, which could have been replaced by verbal phenomena, were observed and described (the fly). Emersons poetic argument was added to Skinners possible and implicit argument: VB has an inherent paradox the wing (the verbal) is the description of the flight (verbal phenomena). This explanation for the transcription of the verse as an epilogue appears on VBs first manuscript, which was written to be presented in the William James Lectures. On that occasion, Skinner (1948) said that the motto contained in the verse was appropriate enough to make explicit the difficulty of speaking about words by using words.

2. Counter-argumentative quoting

((someone) said that , but ).

Based on many other texts on language or literary studies carried out by philosophers, linguists and others, Skinner advocated that the verbal behaviour which produced them was affected by an inaccurate stimulus control. Despite considering such productions inaccurate, he transcribed them in VB possibly because they affected his actions under the control of verbal processes. Those types of texts are part of the tacted subclass counter-argumentative quoting (CAQ): those are responses whose part in the transcription was not credited (regarding one or more aspects) by Skinner. CAQs were also emitted as they reinforced Skinners arguing. Contrary to the reinforcement provided by the AQs, CAQs reinforced the behaviour of contrasting the transcribed (or read) verbal stimulus (or the pressupositions of the transcription) with Skinners argument written under a supposedly accurate stimulus control.

The transcriptions of passages from the Russells work Inquiry into Meaning and Truth exemplify the process: when writing about the qualifying autoclitics of negation, Skinner criticised Russells argument that the reason for saying, for example, No, it is not raining, is in the previous verbal stimulus, that is, in the question Is it raining? . The contrast conveyed between Russells affirmation that negative propositions will arise when you are stimulated by a word but not by what usually stimulates the word and Skinners argument that the stimulus which controls a response to which no or not is added is often nonverbal can be perceived on page 322 from VB.

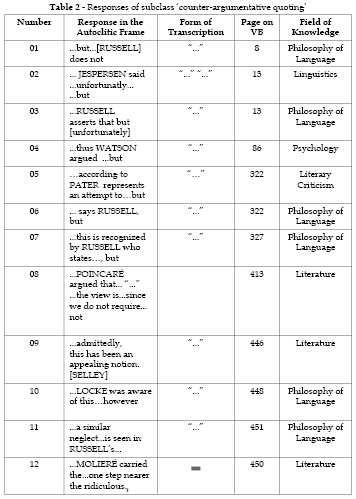

Skinners text elements indicate the most common forms in which CAQs would produce the typical effects of their function. Twenty five occurrences of CAQs were discriminated, as shown in Table 2 below. The topography of the responses varied according to the following: 11 episodes of another authors text in quotation marks: ..., 11 episodes highlighted in the text: (...), 2 episodes of transcription in italics: /// and 1 episode with transcription in quotation marks in a footnote: ....

The preferred targets of Skinners counter-argumentation in quotings with transcriptions were the arguments of language philosopher Bertrand Russell in Inquiry into Meaning and Truth (published in 1940), arguments of literary critic William Empson in Seven Types of Ambiguity (published in 1947) (Skinner counter-arguments specifically aimed at Epsons interpretation of a fragment of Shakespeares LXXIII sonnet and of a line in Coleridges poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner) and arguments contained in Language: its Nature, Development and Origin, published in 1922 by linguist Otto Jespersen.

Other less preferred targets were The Teory of Speech and Language (published in 1932 by A. H. Gardner), Lectures on Poetry (published in 1911 by G. W. Mackail), The Nature of Mathematics (P. Jourdain, 1956) and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Locke, 1947).

Skinner also counter-argumented excerpts of the work Behaviorism, by Watson (1924), and was vehemently against the affirmation of French comedy writer Molière that the meaning of words is found in dictionaries: Molière carried the formalistic argument [on meaning] one step nearer the ridiculous. All that is most beautiful in literature, one of his characters argues, is to be found in the dictionaries. It is only the words which are transposed. (1957: 450). This attack is justified: for Skinner, the meaning of verbal behaviour is not in words or in dictionaries, but in the circumstances which control the utterance of words.

A similar verbal clash concerning the critics animosity occurred in the transcription of Poincarés 1913 work Mathematical Creation and in an unfortunate sentence in Prometheus Unbound, in which the writer P.B. Shelley (1908) advocates that thoughts are the creation of speech. Also, Poincaré affirmed that occasional clarification is a manifest sign of long unconscious work. Table 2 shows the functional details of these and other responses of subclass CAQ .

In the table above, among the 25 responses which compose the CAQs, Bertrand Russell was counter-argumented 9 times in VB. In 5 episodes, Skinner criticised the opinion from linguists Jespersen, Tooke and Gardner, and in other 5 challenged the views from literary critics Pater, Mackeil e Empson. Once more, there is a variety of indicators of autoclitic processes which may have characterized the writing of such parts of VB, in which the emissions of CAQs were reinforced. Many of such forms included adverbs, conjunctions and verbs in the present and past tenses. Generally speaking, it is significant that more than half of CAQs were initiated with the response but. What was also remarkable was the fact that the records showed autoclitic unities of negation (the suffix less and the not) when compared to the sample of records from AQs. The integrative function of autoclitic unities from the CAQs is directly related to the meaning which transcribed texts might have had in Skinners repertoire.

Perhaps the conjunction but is the most emitted manipulative autoclitic in English. It is an abbreviation of the old be out and has preserved the function of mand, according to Tooke (1857 apud Skinner, 1957). In their function, the manipulative autoclitics are verbal unities which, on the occurrence of contrast between two arguments, instruct the reader of VB how to deal with their reactions concerning both arguments in a more effective manner and towards a more accurate verbal behaviour of the contrasting (obviously, Skinners contrasting).

In this perspective, although and however are also manipulative. Although seems to be the combination of all and though and carries a sense of resentment after everything is analysed: possibly Skinners displeasure or disappointment after considering everything good there could be to consider (in the transcription). Although indicated contingencies in the CAQs which were close in meaning with but, but with a small and important difference: the frame of emission of the manipulative though conveys that Skinner has valued some parts of the transcribed material (generally emitted before such unit) and downplayed others.

For instance, the quoting of Jespersen on page 44 of VB is considered. Before, Skinner had argued that the traditional approaches were mistaken in the analysis of manding as they considered its reinforcement as being the object which follows it. Afterwards, he compared the functional analysis with the syntactic analysis relating to manding. Next, he began the paragraph of the transcription by saying that the choice between the two approaches should not consider the intelligibility which some classic approaches may transmit. He then transcribed Jespersens passage and manipulated the reader into recognizing the merits of the transcription and, at the same time, devalue what Jespersen did not take into account. The qualifying autoclitic not opened the transcription analysis by intensifying the expected directions for the verbal behaviour to be reinforced in the mediation: It is not the most advantageous account for all concerned, for the psychological terms it cointains raise many problens.. For all concerned is in italics in VB as its autoclitic function in order to make the originally intended account more precise.

However is a combination between how and ever and its function is to qualify essential operants by tacting a circumstance of repetition involving the content of the quoting in the episode (which could be equivalent to como sempre (in Portuguese) emitted in a context of disappointment). In quoting Locke on page 448 of VB, Skinner praised the author for his autoclitic was aware of this when he affirmed that Locke was aware of the function of some terms which are grammatically classified as nouns. Nevertheless, he went on to express his disappointment towards Lockes analysis of the term triumphus: ...however, the term merely supported the idea for which it stood . Still today, the autoclitic however affects reading by indicating which are the circumstances responsible for a kind of disappointment tacted by Skinner and instructs a redefined reaction towards the transcription so as to avoid such disappointment.

The descriptive autoclitics from CAQs episodes are integrated to the others in a functional coherence. The current standard meaning of the response admittedly informs the contingencies which provided meaning to this operant when it was emitted: I must accept even if I dont want to. Thus, the unit allows for the inference that Skinner outlined his emotional and motivational conditions as being controlled by transcription properties (1957: 446) from the argument of poet Percy B. Shelley in Prometheus Unbound (1820): He gave man speech, and speech created thought, which is the measure of the universe. . The modulation in the reading allows the reader to infer Skinners emotions as he wrote: Even if I dont want to, I have to accept what has been an attractive notion.

In the same network of verbal relations are the responses unfortunately and merely. The autoclitic bearing the suffix ly affected the episodes in which they appear and indicated Skinners conditions in the emission of the CAQs. In the first response, this functional autoclitic fragment signalled Skinners motivational condition concerning the lacking properties in Jespersens verbal response (possibly because of an inaccurate stimulus control, Skinner could have been sorry: Would Jespersen be unfortunate?).

On the same grounds is the analysis to the response merely, which signals the conditions of emission of CAQs involving literary critic Empsons text. His quoting in particular was emitted with a combination of although and merely and the indicators of the former are exacerbated in the disqualification (mere = nothing more than) of Empsons critical analysis in a line of a Coleridges poem.

The quoting of Horatio Pater on page 282 in VB illustrates the effects of an autoclitic of composition (according to) combined with elements from a scheme to reinforce VB readers consequential repertoire. Skinner initiated the sentence containing the quoting by promoting a verbal combination containing Paters specific transcription properties: Style is a certain, absolute and unique manner of expressing a thing, in all its intensity and color. Then, he went on to say that Paters definition represents an attempt to deal with the problem as a matter of successful expression . A discrimination evoked from this text is that Skinner wished to anticipate a contestation to his agreement by providing elements for a functional definition of stylistics which was to be added to Paters literary definition. The counter-argumentation focused on but, which promoted an adequate reflexive position in relation to the core point of the functional definition of stylistics: the anticipated preparation of reader responses.

On the whole, CAQs emitted by Skinner were marked by the manipulative mediation of VBs reader. Relational autoclitics were controlled by relations between Skinners verbal behaviour and transcription properties as recognition of merit (this is recognized, was aware of this, as pointed out, has tried, put a similar point this way) as a polite manner to prepare the emission of the counter-argument. The descriptives informed about Skinners own behavior through transcribed textual stimuli and the operants ridiculous, neglect, objection, against e appealing complemented the counter-argumentative functional coherence.

Conclusion

Conclusions are possible despite of the difficulties of this study. The identification of verbal functional classes in static records is no simple task, mainly when one of the criterion to pinpoint them is the effect of such records in the researchers interpretation. Quoting Empson, one can have the impression that something flies a lot because the verbal is the wing. However, the procedure of the behavioral hermeneutics (specially the fourth step) aims to balance the size of the wing and the height of the flight or prevent the nonsense talk. A limitation of such refined interpretive exercise led to the crucial testing whether the argumentative and counter-argumentative verbal episodes would similarly affect the other analysts, who queried the research which gave rise to this paper. All in all, as in any historical research, the interpretation here presented is one among many possible others.

It is important to remember that proficiency in the English language favours the development of intraverbals which are more efficient to interpretation. Even though, the fact that the researcher had English as a second language has hindered the analysis in certain points. Undoubtedly, the good reader of Skinner who has English as his/her native language would be better able to modulate the reading for the discrimination of the static records dynamic properties in Skinners verbal behaviour. In fact, it is not easy for the researcher to refine the discriminations given the barriers of verbal effect patterns over his/her verbal. This is the reason why it is not possible to clarify all the discriminations made and the reasons for making them, since the verbal behaviour has inexorable limitations in the description of all the active controlling variables (Skinner, 1957, p. 451, quoting the philosopher Emmanuel Kant). A way to minimize this limitation was to talk to fluent speakers of English so as to test senses in autoclitic units which define the Skinnerian writing style in VB.

Style is a product of the autoclitic activity and its functional analysis directs the investigation towards minimal units which modify the first-order operating effect in the repertoire of the reader, therefore composing rhetoric. The complicated task of highlighting the autoclitic structural records had been pointed by Catania (1980), since the process may be present in: fragments of textual elements grammatically defined as words, defined elements such as formatting (underlining, boldfacing etc) and groups of words. Despite this, the importance of such process in historical research is undebatable, since the analysis of autoclitics leads to the discrimination of the researchers verbal behavior regarding the interpretation of the speaker or writers behavioral suitability given the demands of the broad context defined as audience (Catania, 1998).

As a personal product, VB is a portrait of its author. The argumentative and counter-argumentative functional classes described in this paper show the intellectual-scientist struggling to defend his thesis by contrasting the new functional approach and the old traditional approach (Woodward, 1996). One cannot state (as Woodward (1996, did) that Skinner was aware of VBs target audiences. It also cannot be stated (at least concerning the data presented and discussed in this paper) that the artifices of persuasion and argumentation used by Skinner were totally spurious, as he himself admitted at the end of the book (1957: 455). It can be said that the argumentative and counter-argumentative verbal resources were in accordance with the historical context of linguistic studies and with language products during the years in which VB was written and, from this perspective, they cannot be deemed as spurious: they are the authors own resources and are, therefore, genuine and legitimate.

Bibliographical References

Abib, J. A. D. (1994). A atualidade do livro Verbal Behavior de B. F. Skinner: um comentário. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 10, 467-472.

Andresen, J. T. (1990). Skinner and Chomsky thirty years later. Historiographia Linguistica, 17, 145-165.

Borloti, E. B. (2003). O Discurso de Skinner: uma análise funcional do citar no Verbal Behavior. Tese de doutorado. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia (Psicologia Social). São Paulo-SP.

Borloti, E. B. (2004). As relações verbais elementares e o processo autoclítico. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 6, 221-236.

Borloti, E. B., Iglesias, A., Dalvi, C. M., & Silva, D. M. (2008). Análise comportamental do discurso: fundamentos e método. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 24, 101-110.

Bradbent, D. E. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. British Journal of Psychology, 50, 371-373.

Catania, A. C. (1980). Autoclitic process and the structure of behavior. Behaviorism, 8, 175-186.

Catania, A. C. (1998). The taxonomy of verbal behavior. In K. A. Lattal & M. Perone (Ed.). Handbook of research methods in human operant behavior (pp. 405-433). New York: Plennum Press.

Chomsky, N. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior by B. F. Skinner. Language, 35, 26-58.

Coleman, S. R. (1985). B. F. Skinner, 1926-1928: from literature to psychology. The Behavior Analyst, 8, 77-92.

Day, W. (1980). Some comments on the book Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 8, 165-173.

Dougher, M. J. (1993). Interpretative and hermeneutic research methods in the contextualistic analysis of verbal behavior. In S. C. Hayes, H. W. Reese, & T. R. Sarbin (Eds.). Varieties of Scientific Contextualism (pp. 147-159). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Dulaney, D. E. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Science, 129, 143-144.

Farrell, B. A. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, 124-125.

Garfield, E. (1979). Citating indexing its theory and application to science. Technology and humanities. New York: John Wiley.

Gray, G. W. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 44, 196-197.

Jenkins, J. J. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 24, 73-74.

Justi, F., Reis, R. dos, & Araujo, S. de F.. An evaluation of Chomskys review of Verbal Behavior according to behaviorists replies. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 20, 267-274. Recuperado em 30 novembro, 2007, de http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-37722004000300008&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0102-3772

Knapp, T. J. (1992). Verbal Behavior: the other reviews. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, 87-95.

Knapp, T. J. (1980). Beyond Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 2, 187-194.

Knapp, T. J. (1998). Current status and future directions of operant research on verbal behavior: baselines. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 121-123.

Krasner, L. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Human Biology, 30, 350-351.

Lee, V. L. (1984). Some notes on the subject matter of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 1, 29-40.

Leigland, S. (1998). The methodological challenge of the functional analysis of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 125-127.

Mabry, J. H. (1998). Something for the future. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 129-130.

MacCorquodale, K. (1970). On Chomskys review of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 13, 83-99.

Mahl, G. F. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 27, 595-597.

McPearson, A., Bonem, M., Green, G., & Osborne, J. G. (1984). A citation analysis of the influence on research of Skinners Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst, 7, 157-167.

Merriam-Webster (1995). Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, Massachusetts.

Michael, J. (1998). The current status and future directions of the analysis of verbal behavior: comments on the comments. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 157-161.

Morris, C. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Contemporary Psychology, 3, 212-214.

Morris, E. K., & Schneider, S. (1986). References citations in B. F. Skinners Verbal Behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 4, 39-43.

Neimark, E. D. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. Psychological Record, 10, 63-66.

Osgood, C. E. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Contemporary Psychology, 3, 209-212.

Parrot, L. J., & Hake, D. F. (1983). Toward a science of history. The Behavior Analyst, 6, 121-132.

Peel, E. A. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 30, 89-91.

Place, U. T. (1981a). Skinners Verbal Behavior I why we need it. Behaviorism, 1, 1-24.

Place, U. T. (1981b). Skinners Verbal Behavior II what is wrong with it. Behaviorism, 2, 131-152.

Place, U. T. (1982). Skinners Verbal Behavior III how to improve parts I and II. Behaviorism, 2, 117-136.

Place, U. T. (1983). Skinners Verbal behavior IV how to improve part IV Skinners account of syntax. Behaviorism, 2, 163-186.

Place, U. T. (1985). Three senses of the word tact. Behaviorism, 13, 63-74.

Powell, R. P., & Still, A. W. (1979). Behaviorism and the psychology of language: an historical reassessment. Behaviorism, 7, 71-89.

Schlinger, H. D. Jr (1998). The current status and future directions of the analysis of verbal behavior: introductory remarks. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 93-96.

Schnaitter, R. (1980). Science and verbal behavior. Behaviorism, 2, 153-160.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Verbal Behavior The William James Lectures. Western Michigan University: The Association of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. F. (1967/1970). B. F. Skinner an autobiography. In P. B. Dews (Ed.). Festschrift for B. F. Skinner (1-21). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Reprinted from A History of Psychology in Autobiography, vol. V, by E. G. Boring, & G. Lindizey, 1967].

Skinner, B. F. (1978). Reflections on Behaviorism and Society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Skinner, B. F. (1979). The Shaping of a Behaviorist. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Smith, L. C. (1981). Citation analysis. Library Trends, 30, 83-106.

Solley, C. M. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 22, 111.

Sundberg, M. L. (1998). Realizing the potential of skinners analysis of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 143-147.

Tikhomirov, O. K. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Word, 15, 362-367.

Woodward, W. R. (1996). Skinner and Behaviorism as cultural icons: from local knowledge and reader reception. In L. D. Smith, & W. R. Woodward (Ed.). B. F. Skinner and Behaviorism in American Culture (72-92). London: Associeted University Press.

Zehrer, F. A. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 29, 429-430.

Recebido em: 10/30/2007

Primeira decisão editorial em: 11/06/2007

Versão final em: 01/28/2008

Aceito em: 03/02/2008

1This paper is part of the authors PhD dissertation defended for the Graduate Programme of Social Psychology of PUC-SP, under the advising of Prof. Maria do Carmo Guedes. A portion of it was prepared at West Virginia University and at The B. F. Skinner Foundation, under the advising of Prof. Julie S. Vargas. The author acknowledges the special advising given by both scholars and would also like to thank for the suggestions from the following examining committee members: Maria Amália Pie Abib Andery, Maria Martha Hübner and Rachel Nunes da Cunha.

2 PhD in Psychology. E-mail addresses: borloti@hotmail.com

Abib, J. A. D. (1994). A atualidade do livro Verbal Behavior de B. F. Skinner: um comentário. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 10, 467-472. [ Links ]

Andresen, J. T. (1990). Skinner and Chomsky thirty years later. Historiographia Linguistica, 17, 145-165. [ Links ]

Borloti, E. B. (2003). O Discurso de Skinner: uma análise funcional do citar no Verbal Behavior. Tese de doutorado. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia (Psicologia Social). São Paulo-SP. [ Links ]

Borloti, E. B. (2004). As relações verbais elementares e o processo autoclítico. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 6, 221-236. [ Links ]

Borloti, E. B., Iglesias, A., Dalvi, C. M., & Silva, D. M. (2008). Análise comportamental do discurso: fundamentos e método. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 24, 101-110. [ Links ]

Bradbent, D. E. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. British Journal of Psychology, 50, 371-373. [ Links ]

Catania, A. C. (1980). Autoclitic process and the structure of behavior. Behaviorism, 8, 175-186. [ Links ]

Catania, A. C. (1998). The taxonomy of verbal behavior. In K. A. Lattal & M. Perone (Ed.). Handbook of research methods in human operant behavior (pp. 405-433). New York: Plennum Press. [ Links ]

Chomsky, N. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior by B. F. Skinner. Language, 35, 26-58. [ Links ]

Coleman, S. R. (1985). B. F. Skinner, 1926-1928: from literature to psychology. The Behavior Analyst, 8, 77-92. [ Links ]

Day, W. (1980). Some comments on the book Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 8, 165-173. [ Links ]

Dougher, M. J. (1993). Interpretative and hermeneutic research methods in the contextualistic analysis of verbal behavior. In S. C. Hayes, H. W. Reese, & T. R. Sarbin (Eds.). Varieties of Scientific Contextualism (pp. 147-159). Reno, NV: Context Press. [ Links ]

Dulaney, D. E. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Science, 129, 143-144. [ Links ]

Farrell, B. A. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, 124-125. [ Links ]

Garfield, E. (1979). Citating indexing – its theory and application to science. Technology and humanities. New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Gray, G. W. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 44, 196-197. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J. J. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Jouranl of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 24, 73-74. [ Links ]

Justi, F., Reis, R. dos, & Araujo, S. de F.. An evaluation of Chomskys review of Verbal Behavior according to behaviorists replies. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 20, 267-274. Recuperado em 30 novembro, 2007, de http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-37722004000300008&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0102-3772 [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1992). Verbal Behavior: the other reviews. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 10, 87-95. [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1980). Beyond Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 2, 187-194. [ Links ]

Knapp, T. J. (1998). Current status and future directions of operant research on verbal behavior: baselines. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 121-123. [ Links ]

Krasner, L. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Human Biology, 30, 350-351. [ Links ]

Lee, V. L. (1984). Some notes on the subject matter of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism, 1, 29-40. [ Links ]

Leigland, S. (1998). The methodological challenge of the functional analysis of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 125-127. [ Links ]

Mabry, J. H. (1998). Something for the future. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 129-130. [ Links ]

MacCorquodale, K. (1970). On Chomskys review of Skinners Verbal Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 13, 83-99. [ Links ]

Mahl, G. F. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 27, 595-597. [ Links ]

McPearson, A., Bonem, M., Green, G., & Osborne, J. G. (1984). A citation analysis of the influence on research of Skinners Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst, 7, 157-167. [ Links ]

Merriam-Webster (1995). Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

Michael, J. (1998). The current status and future directions of the analysis of verbal behavior: comments on the comments. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 157-161. [ Links ]

Morris, C. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Contemporary Psychology, 3, 212-214. [ Links ]

Morris, E. K., & Schneider, S. (1986). References citations in B. F. Skinners Verbal Behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 4, 39-43. [ Links ]

Neimark, E. D. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. Psychological Record, 10, 63-66. [ Links ]

Osgood, C. E. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Contemporary Psychology, 3, 209-212. [ Links ]

Parrot, L. J., & Hake, D. F. (1983). Toward a science of history. The Behavior Analyst, 6, 121-132. [ Links ]

Peel, E. A. (1960). Review of Verbal Behavior. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 30, 89-91. [ Links ]

Place, U. T. (1981a). Skinners Verbal Behavior I – why we need it. Behaviorism, 1, 1-24. [ Links ]

Place, U. T. (1981b). Skinners Verbal Behavior II – what is wrong with it. Behaviorism, 2, 131-152. [ Links ]

Place, U. T. (1982). Skinners Verbal Behavior III – how to improve parts I and II. Behaviorism, 2, 117-136. [ Links ]

Place, U. T. (1983). Skinners Verbal behavior IV – how to improve part IV Skinners account of syntax. Behaviorism, 2, 163-186. [ Links ]

Place, U. T. (1985). Three senses of the word tact. Behaviorism, 13, 63-74. [ Links ]

Powell, R. P., & Still, A. W. (1979). Behaviorism and the psychology of language: an historical reassessment. Behaviorism, 7, 71-89. [ Links ]

Schlinger, H. D. Jr (1998). The current status and future directions of the analysis of verbal behavior: introductory remarks. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 93-96. [ Links ]

Schnaitter, R. (1980). Science and verbal behavior. Behaviorism, 2, 153-160. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Verbal Behavior – The William James Lectures. Western Michigan University: The Association of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1967/1970). B. F. Skinner an autobiography. In P. B. Dews (Ed.). Festschrift for B. F. Skinner (1-21). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Reprinted from A History of Psychology in Autobiography, vol. V, by E. G. Boring, & G. Lindizey, 1967]. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1978). Reflections on Behaviorism and Society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1979). The Shaping of a Behaviorist. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [ Links ]

Smith, L. C. (1981). Citation analysis. Library Trends, 30, 83-106. [ Links ]

Solley, C. M. (1958). Review of Verbal Behavior. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 22, 111. [ Links ]

Sundberg, M. L. (1998). Realizing the potential of skinners analysis of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 15, 143-147. [ Links ]

Tikhomirov, O. K. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. Word, 15, 362-367. [ Links ]

Woodward, W. R. (1996). Skinner and Behaviorism as cultural icons: from local knowledge and reader reception. In L. D. Smith, & W. R. Woodward (Ed.). B. F. Skinner and Behaviorism in American Culture (72-92). London: Associeted University Press. [ Links ]

Zehrer, F. A. (1959). Review of Verbal Behavior. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 29, 429-430. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em