Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

On-line version ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.7 no.3 Ribeirão Preto Dec. 2011

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Adequacy of nutrition to chemical dependents' profile in a therapeutic community: a case study

Adecuación de la alimentación al perfil de los adictos en una comunidad terapéutica: un estudio de caso

Carla Rosane Paz Arruda TeoI; Luana BaldisseraII; Francielle Rodrigues da Fonseca RechII

IPh.D.

in Food Science, Professor, Universidade Comunitária da Região

de Chapecó, SC, Brazil. E-mail: carlateo@unochapeco.edu.br

IIUndergraduate students in Nutrition, Universidade Comunitária

da Região de Chapecó, SC, Brasil. E-mail: Luana - luanab@unochapeco.edu.br,

Francielle - franciellerfrech@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

The study aimed to evaluate the adequacy of nutrition to institutionalized dependents' profile in a therapeutic community. They (33) answered a semistructured questionnaire to identify the profile and had their weight and height measured. We evaluated 56 lunch menus. Low socioeconomic status (66.7%), low education level (42.4%), alcohol abuse (93.9%) and overweight (45.5%) were found. The menus were rich in leaves (75.0%) and other vegetables (57.0%), fruit (82.1%), and presented high levels of complex carbohydrates (44.6%) and fried foods (35.7 %). It was concluded that nutrition at the evaluated institution contributes to overweight, reinforcing the importance of nutritionists' insertion in the chemical addiction treatment team.

Descriptors: Collective Feeding; Nutrition; Public Health; Substance-Related Disorders.

RESUMEN

El objetivo fue evaluar la adecuación de la alimentación en una comunidad terapéutica al perfil de los adictos. Dependientes (33) respondieron a un cuestionario de perfil; peso y altura fueron medidos. Se evaluaron 56 menús de almuerzo. Se encontró bajo nivel socioeconómico (66,7%) y educativo (42,4%), abuso de alcohol (93,9%), sobrepeso (45,5%). Los menús fueron ricos en verduras (75,0%), hortalizas (57,0%), frutas (82,1%), con altos niveles de hidratos de carbono complejos (44,6%) y frituras (35,7 %). Se concluyó que la alimentación evaluada contribuye al sobrepeso, lo que refuerza la importancia de los nutricionistas en el tratamiento de la adicción.

Descriptores: Alimentación Colectiva; Nutrición en Salud Pública; Transtornos Relacionados com Sustancias.

Introduction

Drug abuse is a public health problem whose consequences are becoming increasingly alarming, with great social impact (1). Currently, there is an urgent reorganization of services that meet users of psychoactive substances, for the inclusion of effective rehabilitation and health promotion (2). In terms of public policy, it was only in 2003 that it emerged in Brazil the Policy for Integral Attention to Users of Alcohol and Other Drugs (3). Due to this historic delay in policy directed to addicts, society was organized in order to fill the gap left by the public powers, providing diversity of clinical and therapeutic communities.

In these spaces, multidisciplinary teams usually do not include dieticians, although it is recognized the interference of psychoactive substance abuse in eating behavior, while many drugs associated with changes in eating habits and nutritional status of the user to affect the appetite and intake of food and / or by acting directly on the absorption and metabolism of specific nutrients(4). It is assumed, therefore, how relevant the development of research on food and nutrition addicts in order to produce knowledge that accrues in qualification of care, improving care and, consequently, greater adherence and treatment success. In this context, the objective of this study was to assess the adequacy of food distributed in a therapeutic community, the profile of a group of institutionalized drug addicts there.

Casuistry and Method

General characteristics of the study

The exploratory quantitative research was held in a therapeutic community, social welfare institution, Chapecó, SC, in the period from February to March 2009. The study population comprised 33 chemically dependent men, aged 18 years and signed an informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Unochapecó (No. 199/08) and responded to Resolution 196/96, of the National Health Council - CNS.

Socioeconomic, demographic and addiction profile

It was applied a semi-structured questionnaire with seven questions, developed by the researchers. For the socioeconomic assessment it was used the Brazil Economic Classification Criterion (5).

Nutritional and Feeding Profile

Designed by body mass index (BMI) and semi-structured questionnaire specifically for this purpose (4). The BMI classification followed the cutoffs of the Feeding and Nutritional Surveillance System - Sisvan(6).

Evaluation of menus

The institution's lunch menus collected during 56 consecutive days were analyzed by adapting the methodology Qualitative Assessment of Menu Preparations (AQPC)(7). The criteria were adapted for this study harmony of colors (dull when the supply of preparations with up to two different colors, excluding rice and beans), presence of sulfur foods (excessive when the supply of two or more foods rich in sulfur, excluding beans), and supply of complex carbohydrates (excessive when the presence of three or more food sources of these nutrients at the same meal).

Processing of data

We used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 16.0), and the data expressed by descriptive statistics and absolute and relative frequencies. The association between variables was analyzed with the chi-square test of Pearson (p<0.05).

Results

Socioeconomic, demographic and addiction profile

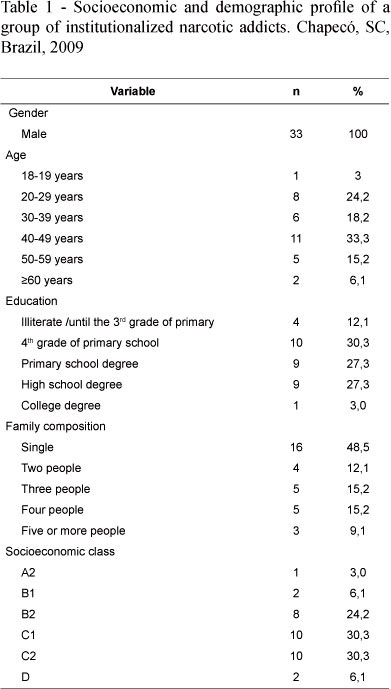

The socioeconomic and demographic profile was drawn from the variables gender, age, education, family composition and socioeconomic status, and is detailed in Table 1. The mean age was 25.7 years (+6.59), with minimum 18 and maximum of 68 years. Educational level was low, with 42.4% (n = 14) of them not having completed elementary school. Categorized according to the Brazil Economic Classification Criterion(5), 66.7% (n = 22) of respondents were located in classes C and D together, 30.3% (n = 10) in B and 3% (n = 1) in Class A2.

In order to profile the dependency, alcohol was nominated as the first drug consumption by 60.6% (n=20) of respondents, and associated with the main drug used was cited by 93.9% (n=31) of subjects Search. Furthermore, 66.7% (n=22) of respondents reported having used tobacco, 39.4% (n=13) of marijuana, 39.4% (n=13) of cocaine, 36.4% (n=12) crack, 15.1% (n=5) smell ether, 15.1% (n=5) of hashish, 9.1% (n=3) ecstasy, 6.1% (n=2) of glue and merla 3% (n=1) and LSD 3% (n=1) of mushroom. Accordingly, 30.3% (n=10) of respondents reported being dependent on a substance, 48.5% (n=16) of two substances and 21.2% (n=7) of three substances.

Behavior change was identified by age group: 88.8% (n=16) of subjects with more than 40 years started using drugs with alcohol or tobacco and 53.3% (n=8) of respondents under 40 year began with an illicit drug. Most respondents (72.7%, n=24) also reported previous treatment and 27.3% (n=9) of them were in their first attempt. Regarding the time of admission, 51.5% (n=17) of the subjects were in the institution for less than one month, 39.4% (n=13) between 1 and 5 months and 9.1% (n=3) more than 5 months.

Nutritional and feeding profile

The nutritional profile of the evaluated group showed normal weight of 54.5% (n=18) subjects, overweight 36.5% (n=12) and obesity was 9% (n=3). For the nutritional profile, it is noted that 93.9% (n=31) of respondents reported changes in eating habits in the period prior to hospitalization, such as reduction or increase of appetite, nausea and vomiting. Among those who reported changes, 6.5% (n=2) related directly to the type of drug used in the reactions thereon, stating that crack and marijuana caused, respectively, decreased and increased appetite.

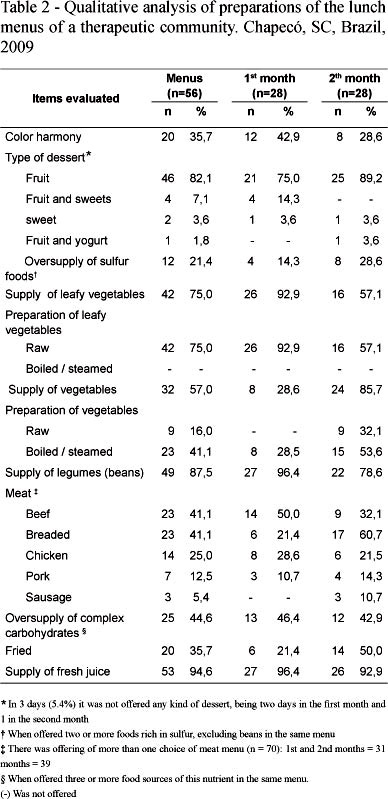

Evaluation of menus

At the institution where this research was carried out they served three meals daily (breakfast, lunch and dinner). It is justified the choice of lunch menus for this analysis as it is the largest meal of the day there. The results of the analysis of 56 menus are summarized in Table 2.

In addition to these we highlighted other observations deemed relevant for this study.

The supply of liquid at lunch in the institution was observed in 100% (n=56) of the menus, this offer was represented by soft drinks in 5.4% (n=3) in the period of the menus and orange juice in the other (94.6%, n=53). The supply of leafy vegetables and vegetables had low variety, having been observed the presence of lettuce in 71.4% (n=40) of the menus, tomato 19.6% (n=11) and cabbage in 19.6% (n=11). For fruit, the diversity was also low, being available daily mandarin (a variety of tangerine), orange and papaya.

For the group of meat, it was found that 25% (n=14) of menus over a food was made available. Considering the amount of meat present in the menus (n=70), there was predominance of preparations of beef and breaded foods (65.7%, n=46), it is appropriate to score, yet the high (37.1%, n=26) supply of formulated meat products (sausages and breaded beef). In relation to the preparation technique, 14.3% (n=10) preparations of meat were fried, and the remaining (85.7%, n=60) roasted, cooked in sauce or sautéed. Regarding the supply of food source of complex carbohydrates, in 96.5% (n=54) of the menus it was present rice and in 33.9% (n=19) pasta, in 46.4% polenta (n=26), in 33.9% cassava (n=19), 12.5% †potato (n=7), and squash 10.7% (n=6), a total of 131 prepared in 56 menus. Therefore, there was a combination of three to five of these foods at one meal by 44.6% (n=25) of the menus. The frying technique was used to prepare foods in this group 17.8% (n=10) of the menus.

Overall, the fry preparation technique was adopted in 25 (12.4%) of all meat preparations (n =70) and food sources of complex carbohydrates (n=131) evaluated the 56 menus, with two frying per meal in five (8.9%) menus, one in the first month and four in the second month.

Foods with higher repetition frequency between the menus evaluated were rice (96.4%, n = 54), beans (87.5%, n = 49), lettuce (71.4%, n = 40), juice natural orange (94.6%, n = 53) and fruits (91.1%, n = 51).

A final aspect to note the analysis of the menus is the irregularity of the results, that is, except for the supply of fruits and sweets, beans and rice, chicken and pork, supply of juice and excessive presence of food sources of carbohydrates complex, all other items evaluated showed greater concentration of supply in one of two months of the study period.

Discussion

The dependent group consisted exclusively of men, since the institution where the study was developed for women does not receive treatment. Regarding the age of internal similarity was observed with data from addicted institutionalized in a therapeutic community of Maringa, Parana, Brazil (4), who were aged between 17 and 64 years. Specifically in relation to alcohol, the literature indicates that there is concentration dependence in the adult audience, aged 20-49 years (8), which is consistent with the results of this study.

The education level of respondents is consistent with the observations of another study, when it was reported that 38% of addicts had low education, limited to the elementary school. Also, it is recognized that involvement with drugs raises school dropout rates and low education, emphasizing the social vulnerability of dependent (9). Referring to family composition, the present study found a predominance of residence alone. Researchers from the theme (10), in describing the experiences of addicts, reported that the choice of drugs involves leaving home, a situation that could explain the results obtained in this study.

The low socioeconomic level of the group of addicts in this assessment is also in agreement with the observations of previous studies. A survey conducted in São Paulo, with 45 ex-crack-dependents, similar to the profile identified in this study and the sample was constituted at the time, mostly by young men, unmarried, low education, without formal employment ties, of low socioeconomic status (11). The same situation was reported in other studies (9,12), which indicate low monthly income, in general. This scenario echoes, certainly in the acquisition and consumption of food, a condition that is exacerbated among addicts by giving priority to the purchase of the drug on food (10), and because it is common to live alone, which makes consumption drugs an aggravating already compromised nutritional status of dependents.

Checking the predominant use of alcohol, it is important to point out that, provided legal drug, the substance acts as a sort of initiation that precedes the use of other drugs, illicit (13). In addition, alcohol abuse is because of poor nutrition by interfering with the selection process, and digestion of food consumption, as well as the absorption and metabolism of nutrients (4). As has been observed in this study, the literature indicates that alcohol; marijuana, cocaine, solvents, crack and amphetamines are the most used drugs currently used so often associated condition known as polydependency (14).

Although the majority of the population to be eutrophic, there was high prevalence of overweight (45.5%), which has been reported in other studies, ranging between 21.1 and 79% ( 4,15-16). This finding is probably related, among other factors, the compensatory feed intake during withdrawal. In relation to perceived changes in eating habits, the data observed in this study are consistent with the findings of another study, when it was observed that 98% of addicts said they noticed changes in their food consumption as a result of drug use (4). The results now obtained are also consistent with the literature that shows marijuana as a stimulator of appetite, especially for sweet foods (4,15,17), and amphetamines and cocaine and anorectic, and stopping consumption of these latter also leads to increased appetite (18), which may also contribute to high rates of overweight observed among drug addicts in treatment.

It should be noted also that the high percentage observed in this study for dependents with a period of institutionalization less than one month and those who reported previous attempts at treatment, indicating high turnover in the institution evaluated, due to poor compliance and high relapse rate. This fact provokes the search for alternatives for the organization of services that can improve adherence to therapy and the level of self-care for recovery and health promotion in this population.

The socioeconomic, demographic variables of nutritional profile and chemical dependency were tested for their possible relationship has not been detected any associations, probably due to sample size, which constitutes a limitation of this study and remains a demand for future investigations.

Regarding the menus, the set of colors that make up the preparation, when harmonic it highlights healthy eating and enjoyable, since different colors incorporate diversity of micronutrients and make the meal more attractive (19). Therefore, the high percentage of monotonous menus considered in this study (64.3%, n = 36), and the colors of the preparations, it was considered as a negative aspect.

Within the composition of the menu, it is recommended to consume three daily servings of vegetables (leafy vegetables and) and three fruits, preferably raw prepared to minimize nutrient losses (20). Thus, the supply of vegetables, leafy vegetables and fruits evaluated in the menus, and how to prepare, mostly raw, were considered very positive aspects, especially for nutrients where these foods are generally rich (vitamin C, provitamin A, vitamin B complex, iron, calcium, potassium and magnesium) (7.21 to 23), which are often in deficit drug (8). An adequate supply of these foods also contributes to reducing the risk of developing chronic non-transmissible (23), both by the intake of micronutrients and fiber. The low supply of sweets and soft drinks during the period is highlighted as a positive aspect, especially when considering the nutritional status of the group and the high content of sugar, fat and therefore calories of these foods.

The oversupply of sulfur foods (high in sulfur), the menus analyzed was low. However, it is considered that could still be quite limited, since these foods when consumed in excess in a single meal, causing discomfort and excessive intestinal gas. On the other hand, are generally of anticarcinogenic properties, for which reason should not be excluded from the planning of menus (7). These foods were represented in this study for broccoli, cauliflower and cabbage.

The daily supply of meat products, although positive, was considered inappropriate in general, due to the frequency of breaded foods, whose habit suggests frying under preparation, suggesting the need for educational initiatives to encourage adoption of healthy preparation techniques. The low supply of pork was found to be negative, depending on the region where is located the institution in question is a major producer of food, which is part of the local food culture. Moreover, breaded and sausages, food formulated significant presence in the menus evaluated are generally poor in nutrients, specifically iron, nutrient especially required by addicts, including iron deficiency anemia is a common finding (8).

Regarding the group of pulses, we observed a low variability. Despite the high acceptance of the daily presence of beans on menus in general, due to the feeding habits of Brazil, it is suggested that the group of other food legumes, menus inserted into this audience, such as lentils, peas, chick-peas, beans white and soybeans, contribute to the intake of fiber and B vitamins, plus iron and calcium (20), minerals that have increased demand among drug addicts (8). Aside from this aspect, the diversification of legumes in menus reduces the monotony, making meals more diverse and attractive, and could be a nutrition education strategy for this audience, reflecting on their families.

On the negative side of the menus evaluated also highlighted the high levels of fries and a glut of food sources of complex carbohydrates, for contributing to excess weight and the development of other chronic diseases (16). Among the drawbacks identified in the menus is still low variety within food groups in general (vegetables, leafy vegetables, fruits, cereals, legumes), which can be explained by the use of food from donations and production in the garden of the institution. In this sense, the lack of variety in the flavor of the juice, apparently a negative aspect was considered outweighed by the high acceptance of orange juice has the general population and the fact that provide excellent intake of vitamin C, essential to enhance the absorption the non-heme iron contained in plant foods prepared in the same meal (24-25).

Finally, one last question considered very negative in the menus of the institution was the irregularity of most of the items evaluated, with greater concentration of supply in one of two months of the study period. These two points show a lack of planning in the preparation of the menus at the expense of meeting the nutritional and emotional needs of the public, as well as the rationality of the use of available resources, in terms of raw materials (ingredients) and equipment and personnel.

The dependence of the organization makes donations to maintaining the variety of the menu difficult, indeed. However, the absence of a professional dietitian to plan menus suited to the irregular availability of food from these donations, contributing to the imbalances in the set of menus evaluated. These imbalances, associated with low fractionation meals at the institution and the tendency among addicts to higher consumption of foods with high energy density in exchange for drugs (15), favor weight gain during the course of treatment.

Conclusion

The profile of addicts in treatment in the institution being evaluated was characterized by low education, low socioeconomic status, prevalence of the age group of 40-49 years and as the drug of first contact and greater alcohol consumption. The nutrient profile moved between the normal weight and overweight, which is compatible with the effect of main drugs of use and also suggestive of increased food consumption during treatment, possibly replacing the drug of dependence, as compensation.

In this context, it is concluded that, although appropriate to the local food culture, in general, and socioeconomic profile of the evaluated group, the menu was constituted as a contributing factor to being overweight and the development of comorbidities related to food, both the low and fractionation by imbalances between food groups and the high supply of fry observed. Based on these, it remains relevant to implementation of actions aimed at recovering and maintaining the nutritional status of the public, increasing nutritional care that includes comprehensive planning appropriate menus and health promoters.

References

1. Matosa M, Pinto FJM, Jorge MSB. Grupo de orientação familiar em dependência química: uma avaliação sob a percepção dos familiares participantes. Rev Baiana Saúde Pública. 2008;32(1):58-71.

2. Ribeiro M. Organização de serviços para o tratamento da dependência do álcool. Rev Bras Psiquiatria. 2004;26:59-62.

3. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria Executiva. Coordenação Nacional de DST/AIDS. A Política do Ministério da Saúde para atenção integral a usuários de álcool e outras drogas. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2003.

4. Oliveira ERN, Marin IC, Feruzzi L, Tenório MFS, Trindade E. Avaliação dos hábitos alimentares e dos dados antropométricos de dependentes químicos. Arqui Ciênc Saúde Unipar. 2005;9(2):91-6.

5. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). [Internet]. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil; 2009. [acesso 10 jul 2009]. Disponível em: www.abep.org.

6.. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Sistema de Vigilância Alimentar e Nutricional (SISVAN). [Internet]. Orientações para a coleta e análise de dados antropométricos em serviços de saúde; 2008. [acesso 7 mai 2009]. Disponível em: http://nutricao.saude.gov.br/documentos/sisvan_norma_tecnica_preliminar.

7. Proença RPC, Sousa AA, Veiros MB, Hering B. Qualidade nutricional e sensorial na produção de refeições. Florianópolis: Ed. da UFSC; 2005.

8. Reis NT, Rodrigues CSC. Nutrição clínica no alcoolismo. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2003.

9. Quimelli GAS, Krainski LB, Cordeiro MS. Perfil dos usuários dependentes de drogas do programa pró-egresso (PPE) de Ponta Grossa. Rev Conexão UEPG. 2008;3:54-8.

10. Rigotto SD, Gomes WB. Contextos de abstinência e recaída na recuperação da dependência química. Psicol Teoria Pesqui. 2002;18(1):95-106.

11. Oliveira LG, NAPPO SA. Caracterização da cultura de crack na cidade de São Paulo: padrão de uso controlado. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42(4):664-71.

12. Ferigolo M, Barros HMT, Fuchs FD, Stein AT. Influence of depression and early adverse experiences on illicit drug dependence: a case-control study. Rev Bras Psiquiatria. 2009;31(2):106-13.

13. Sanchez ZVM, Nappo SA. A seqüência de drogas consumidas por usuários de crack e fatores interferentes. Rev Saúde Pública. 2002;36:420-30.

14. Ballani TSL, Oliveira MLF. Uso de drogas de abuso e evento sentinela: construindo uma proposta para avaliação de políticas públicas. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2007;16(3):488-94.

15. Grilo CM, O'Malley SS. Eating disorders and alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:151-60.

16. Souza FFA, Abreu RNDC, Costa FLP, Brito EM, Vasconcelos SMM, Escudeiro SS, et al. Pessoas em recuperação do alcoolismo: avaliação dos fatores de risco cardiovasculares. SMAD, Rev Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [periódico na Internet]. 2009;5(2):1-14. Disponível em: http://www2.eerp.usp.br/resmad/artigos.php?idioma=portugues&&volume=5&ano=2009&numero=2

17. Borini P, Borini SB, Guimarães RC. Usuários de drogas ilícitas internados em hospital psiquiátrico: padrões de uso e aspectos demográficos e epidemiológicos. J Bras Psiquiatria. 2003;52(3):171-9.

18. Piran N, Robinson SR. Associations between disordered eating behaviors and licit and illicit substance use and abuse in a university sample. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2006;31(10):1761-75.

19. Felipe MR. Atenção alimentar e nutricional a turistas idosos: um estudo da rede hoteleira de Balneário Camboriú (SC) [tese na Internet]. Balneário Camboriú (SC): UNIVALI; 2006.[ acesso 20 set 2009]. Disponível em: http://www6.univali.br/tede/tde_arquivos.

20.Guia alimentar para população brasileira: promovendo a alimentação saudável. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006.

21. Claudino H. Os vegetais, alimentos que promovem qualidade de vida. 2.ed. São Paulo: Elevação; 2006.

22. Borjes LC. Concepção da classificação de vegetais para aplicação no sistema de avaliação da qualidade nutricional e sensorial - AQNS. [tese na Internet]. Florianópolis (SC): Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2007. [acesso 12 set 2009]. Disponível em: http://www.tede.ufsc.br/teses/PNTR0027-D.pdf.

23. Castro MBT, Anjos LA, Lourenço PM. Padrão dietético e estado nutricional de operários de uma empresa metalúrgica do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20(4):926-34.

24. Borsoi MA. Nutrição e Dietética: noções básicas. 11.ed. São Paulo: SENAC; 1995.

25. Philippi ST. Pirâmide dos alimentos: fundamentos básicos da nutrição. Barueri: Manole; 2008.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Carla Rosane Paz Arruda Teo

Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó

Área de Ciências da Saúde

Av. Senador Attilio Francisco Xavier Fontana, 591 E

Bairro: Engenho Braun

CEP: 89809-000, Chapeco, SC, Brasil

E-mail: carlateo@unochapecó.edu.br

Received: Abr.

8th 2010

Accepted: Sept. 9th 2011

1. Matosa M, Pinto FJM, Jorge MSB. Grupo de orientação familiar em dependência química: uma avaliação sob a percepção dos familiares participantes. Rev Baiana Saúde Pública. 2008;32(1):58-71. [ Links ]

2. Ribeiro M. Organização de serviços para o tratamento da dependência do álcool. Rev Bras Psiquiatria. 2004;26:59-62. [ Links ]

3. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria Executiva. Coordenação Nacional de DST/AIDS. A Política do Ministério da Saúde para atenção integral a usuários de álcool e outras drogas. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2003. [ Links ]

4. Oliveira ERN, Marin IC, Feruzzi L, Tenório MFS, Trindade E. Avaliação dos hábitos alimentares e dos dados antropométricos de dependentes químicos. Arqui Ciênc Saúde Unipar. 2005;9(2):91-6. [ Links ]

5. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). [Internet]. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil; 2009. [acesso 10 jul 2009]. Disponível em: www.abep.org. [ Links ]

6.. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Sistema de Vigilância Alimentar e Nutricional (SISVAN). [Internet]. Orientações para a coleta e análise de dados antropométricos em serviços de saúde; 2008. [acesso 7 mai 2009]. Disponível em: http://nutricao.saude.gov.br/documentos/sisvan_norma_tecnica_preliminar. [ Links ]

7. Proença RPC, Sousa AA, Veiros MB, Hering B. Qualidade nutricional e sensorial na produção de refeições. Florianópolis: Ed. da UFSC; 2005. [ Links ]

8. Reis NT, Rodrigues CSC. Nutrição clínica no alcoolismo. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2003. [ Links ]

9. Quimelli GAS, Krainski LB, Cordeiro MS. Perfil dos usuários dependentes de drogas do programa pró-egresso (PPE) de Ponta Grossa. Rev Conexão UEPG. 2008;3:54-8. [ Links ]

10. Rigotto SD, Gomes WB. Contextos de abstinência e recaída na recuperação da dependência química. Psicol Teoria Pesqui. 2002;18(1):95-106. [ Links ]

11. Oliveira LG, NAPPO SA. Caracterização da cultura de crack na cidade de São Paulo: padrão de uso controlado. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42(4):664-71. [ Links ]

12. Ferigolo M, Barros HMT, Fuchs FD, Stein AT. Influence of depression and early adverse experiences on illicit drug dependence: a case-control study. Rev Bras Psiquiatria. 2009;31(2):106-13. [ Links ]

13. Sanchez ZVM, Nappo SA. A seqüência de drogas consumidas por usuários de crack e fatores interferentes. Rev Saúde Pública. 2002;36:420-30. [ Links ]

14. Ballani TSL, Oliveira MLF. Uso de drogas de abuso e evento sentinela: construindo uma proposta para avaliação de políticas públicas. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2007;16(3):488-94. [ Links ]

15. Grilo CM, O'Malley SS. Eating disorders and alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:151-60. [ Links ]

16. Souza FFA, Abreu RNDC, Costa FLP, Brito EM, Vasconcelos SMM, Escudeiro SS, et al. Pessoas em recuperação do alcoolismo: avaliação dos fatores de risco cardiovasculares. SMAD, Rev Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [periódico na Internet]. 2009;5(2):1-14. Disponível em: http://www2.eerp.usp.br/resmad/artigos.php?idioma=portugues&&volume=5&ano=2009&numero=2 [ Links ]

17. Borini P, Borini SB, Guimarães RC. Usuários de drogas ilícitas internados em hospital psiquiátrico: padrões de uso e aspectos demográficos e epidemiológicos. J Bras Psiquiatria. 2003;52(3):171-9. [ Links ]

18. Piran N, Robinson SR. Associations between disordered eating behaviors and licit and illicit substance use and abuse in a university sample. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2006;31(10):1761-75. [ Links ]

19. Felipe MR. Atenção alimentar e nutricional a turistas idosos: um estudo da rede hoteleira de Balneário Camboriú (SC) [tese na Internet]. Balneário Camboriú (SC): UNIVALI; 2006. [acesso 20 set 2009]. Disponível em: http://www6.univali.br/tede/tde_arquivos. [ Links ]

20.Guia alimentar para população brasileira: promovendo a alimentação saudável. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006. [ Links ]

21. Claudino H. Os vegetais, alimentos que promovem qualidade de vida. 2.ed. São Paulo: Elevação; 2006. [ Links ]

22. Borjes LC. Concepção da classificação de vegetais para aplicação no sistema de avaliação da qualidade nutricional e sensorial - AQNS. [tese na Internet]. Florianópolis (SC): Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2007. [acesso 12 set 2009]. Disponível em: http://www.tede.ufsc.br/teses/PNTR0027-D.pdf. [ Links ]

23. Castro MBT, Anjos LA, Lourenço PM. Padrão dietético e estado nutricional de operários de uma empresa metalúrgica do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20(4):926-34. [ Links ]

24. Borsoi MA. Nutrição e Dietética: noções básicas. 11.ed. São Paulo: SENAC; 1995. [ Links ]

25. Philippi ST. Pirâmide dos alimentos: fundamentos básicos da nutrição. Barueri: Manole; 2008. [ Links ]

Received: Abr.

8th 2010 Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Carla Rosane Paz Arruda Teo

Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó

Área de Ciências da Saúde

Av. Senador Attilio Francisco Xavier Fontana, 591 E

Bairro: Engenho Braun

CEP: 89809-000, Chapeco, SC, Brasil

E-mail: carlateo@unochapecó.edu.br

Accepted: Sept. 9th 2011

text in

text in