Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

versão On-line ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.10 no.2 Ribeirão Preto ago. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v10i2p51-60

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DOI: 10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v10i2p51-60

The evolution of anti-drug laws: treatment for drug users and addicts in Brazil and in Portugal

Carla Aparecida Arena VenturaI; Débora Aparecida Miranda BenettiII

IPhD,

Associate Professor, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São

Paulo, WHO Collaborating Centre for Nursing Research Development, Ribeirão

Preto, SP, Brazil

IIProfessor,

Centro Universitário Barão de Mauá, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

With the enactment of the Drug Law, Law no 11,343/2006, Brazil established the proposal of treating addicts and users with more dignity, seeking to treat rather than punish them. In 2000, Portugal, also concerned with the dignity of drug addicts and users, showed a more innovative attitude than that of Brazil, decriminalizing the use of small quantities of drugs. In this context, this reflection compares recent legislation in the two countries, especially regarding differentiating between drug users/addicts and drug dealers and the way their respective treatment. Despite legal changes in Brazil, public health programs that deal with the drug problems in that country remain incipient. The experience of Portugal, then, can provide important elements in designing more effective policies that take into consideration national peculiarities and the multi-dimensionality of the drug phenomenon in Brazil

Descriptors: Street Drugs; Therapeutics; Punishment; Health.

Introduction

The enactment of Law no 11,343 in 2006 showed that the authorities in Brazil were attempting to adapt legislation to international directives differentiating drug users and addicts from the figure of the drug dealer.

Although discussion continues here on the subject of decriminalizing drug users and addicts, especially in article 28 of the above mentioned law, the new legislation can be said to have made advances on this topic, as drug users or addicts are referred for treatment and no longer sent to prison.

In this situation, it is noteworthy that Portugal modified the treatment given to drug users or addicts before Brazil did so. Taking a daring attitude, they decriminalized possession of small quantities of drugs. Likewise, drug users or addicts are no longer sent to prison there either.

Considering the proximity that exists between Brazilian and Portuguese culture and legal systems, as well as the similar decisions on legally differentiating drug users and addicts from dealers, this theoretical reflection describes the legal directives for treating drug users or addicts in Brazil and in Portugal.

Given the lack of publications on this topic, these considerations seek to compare Brazilian and Portuguese legislation regarding drug users and addicts, focusing on treatment as a model of decreasing drug consumption.

Drugs and legislation in Brazil

Illegal drug legislation in Brazil has evolved from total punishment – irrespective of whether the individual is a dealer or an addict – towards growing concern for addicts and users. In this country, the first criminal legislation to punish drug use and dealing is Book V of the Filipinas Ordinances. Later came the 1890 Republican Penal Code, the 1932 Consolidation of Penal Law, Decree no 780, modifying Legal Decree no 891 in 1938 and the 1940 Penal Code, followed by sparse legislation on which we will comment later(1) starting with Law no 6,368/1976.

One of the articles in this 1976 law punished drug users with between 6 months and 2 years of imprisonment, thus restricting individual liberty. Possession for personal use was, then, criminal, with the individual often imprisoned without any proper treatment, in a vulnerable condition.

Some alterations were later made in favor of users with Laws no 9,099/1995 and no 10,259/2001. In 2002, Law no 10,409 was approved, in order to abolish Law no 6,368/1974. However, this did not occur, as the then-President of the Republic vetoed part of the legislation, creating various difficulties in its applicability, as both laws applied.

In this context of duality, in 2006, Law no 11,343 was promulgated with the arduous purpose of resolving the problem, giving greater security to society given the disorder of the applicability of the previously published laws.

To better understand the modifications in the above mentioned laws, Figure 1 gives a brief comparison of the principal articles of the legislation, focusing on drug users, addicts and dealers.

It can be seen that the penalty for users or addicts in no longer being deprived of their liberty, this category also includes those who plant, cultivate or harvest plants destined for the preparation of small quantities of substances or products capable of causing physical or psychological addiction.

By comparing the laws, it is confirmed that the minimum sentence and fine for dealing drugs were increased. The expression "narcotic substance or those capable of causing physical or psychological addiction" was modified to "drugs". Regarding raw materials, the only alteration was to update the description of the crime, without further modifications.

When comparing the two legislations, in the case of planting, if the quantity cultivated was small and for personal use, the agent will be considered a user or addict. In the case of a large quantity, the agent will be viewed as a drug dealer.

At the time of the previous law, there was a lot of controversy on how the conduct of those who gave away drugs to third parties in order to take them together fitted in. there was no specific expression concerning how to punish them. Sometimes they were punished as drug dealers, at other times as addicts. With the enforcement of the new law, this was defined.

The new law does not discriminate between health care professionals, inferring that all are included to the extent of their competence. It is important to point out that the current law also determines that, in the event of conviction, the judge will communicate this to the Professional Association to which they belong. We must also highlight that this action can be ‘culpable', i.e. committed without intention.

Comparing the content of Laws no 6,368/1976 and no 11,343/2006, shows that the user and/or addict are nowadays treated as individuals in need to treatment and information, in contrast to the 1976 Law, which views them as merely criminals. It is noteworthy that in the current law issues relative to users or addicts can be found in the chapter dealing with the crimes. The dealer is treated more rigorously, with penalties of between 5 and 15 years.

According to Drug Law no 11,343/2006, the judge will determine that drug addicts receive free treatment a health care establishment, preferably on an outpatient basis. If outpatient treatment is not possible, institutionalization is resorted to. Treatment will often be in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). It is therefore the judge's obligation, upon sentencing, to determine this measure.

It is also worth noting that, in this context, the Ministry of Health coordinated new ways of increasing and qualifying the care of Brazilians addicted to crack, alcohol or other drugs(2). Among the measures, the emphasis is on social reintegration and SUS use, with the goal of integrated patient care based on transfer of funds from the Ministry of Health to the States and Municipalities.

Finally, there are legal dispositions on treatment, although it is essential that the legislation be effective and applicable, as drug addiction is a public health problem.

Confirming the status of drug addiction as a public health problem, a judge from the 7th Public Treasury Court in São Paulo recently gave an injunction prohibiting the Military Police from preventing drug addicts in the Cracolândia area of the city from circulating in the streets. The judge stated that it was the State's duty to provide care to drug addicts, through the SUS(3).

Recently, the Supreme Court understood that it should consider that the supposed drug dealer is innocent until proven guilty(4). It should be pointed out that even today such analysis remains at the criterion of the judge who analyzes the case.

On the 28th May 2012, the legal commission discussing the reform of the Penal Code in the Senate approved the decriminalization of drug use for those caught with a quantity equivalent to five days consumption, as defined by the health authorities. However, if the individual is in the presence of children and adolescents, or near to schools or other places with a concentration of children and adolescents, this decriminalization is not effective(5).

Finally, the constant instability of this subject is recognizable, it is an extremely changeable topic, constantly updated. Thus, in early 2013, the State of São Paulo signed up to a project to make compulsory institutionalization for addicts viable. Apparently, the possibility of such institutionalizations will follow these steps: 1- the drug users are approached by community health agents and persuaded to attend a Referral Centre for Drug Addicts (in some cases, weaker addicts are taken to hospital before the referral center); 2- a doctor evaluates whether it is necessary to institutionalize the patient, who is invited to have treatment; 3- if they accept, the institutionalization is voluntary, and the patient is referred for treatment; 4- if they refuse treatment, institutionalization will be compulsory. The District Attorney evaluates the medical reports and delivers an opinion to the judge who may or may not order institutionalization(6).

Drugs and Legislation in Portugal

In the 1990s, Portugal had the highest rate of drug abuse, especially heroin.

Based on a comparison with the European Union context, drug use was clearly higher in Portugal than in the other countries. The consequence was a high crime rate as well as the proliferation of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, hepatitis B and C through contaminated syringes(7).

Faced with the high rate of drug use by the Portuguese population, the authorities wanted to reduce this rate and, automatically, reduce drug-related crimes. In that scenario, as Glen Greenwald explains, a council of specialists, the members of which were doctors, psychologists, doctors in drug policy and a sociologist, was convened in order to discuss the situation, asking if there was an effective way of solving the drug use problem(7).

The commission worked on this mandate for 18 months. At the end of this period they published an academic report indicating decriminalization as the best way of decreasing the serious drug problem. Starting with the legal formalities, Portugal headed towards decriminalizing drug consumption rather than legislation, as the country is a signatory of various international treaties that do not allow such conduct.

In the year 2000, as a result of this movement, Law no 30/2000 of 22nd January, which revoked several articles of Legal Decree no 15/93, was edited. Legal Decree no 15/93 deals with dealing and consuming narcotics and psychotropic substances and presents 76 articles and tables on the types of prohibited drugs. Repressing drug dealing in Portugal is clearly expressed.

Thus, in general, if an individual is arrested consuming or carrying illegal substances in quantities not exceeding 10 days personal consumption (verified on a case by case basis, as exceeding the limit is classed as dealing), they are passed on to a Discussion Commission for a clinical analysis in order to determine whether the individual is an addict or a recreational users, as treatment differs in each case(7).

In the case if addiction, the individual will be invited to attend a treatment center. The individual may not accept the treatment, but if they are arrested again for consuming drugs they may be subject to penalties, such as community service, having license to carry arms for defense, hunting, training or recreation forfeited, prohibited or revoked, having social security benefits revoked or being banned from frequenting certain places, among others. The sanctions are outlined in articles 15 and 17 of Law no 30/2000.

If use is deemed to be recreational, the individual is referred for treatment, giving them the opportunity to discuss situation related to their personal life with others.

It is worth noting that article 40 of Legal Decree no 15/93 determines that the crime of drug consumption carries a penalty of 3 months imprisonment or a fine of up to 30 days or, in the case of substances exceeding what is needed for an average of 5 days consumption, penalty of 1 year in prison or a fine of 120 days, the value of which is set at the trial. Previously, in cases of occasional use, the penalty could be waived. Today, the article has been revoked by Law no 30/2000, although this only refers to consumption, with the crime of cultivation dealt with in article 28 of Law no 30/2000.

It is also important to highlight that the aim of decriminalization in Portugal was not to cease to censure drug consumption.

As drug consumption is of great concern, it is opportune to introduce, briefly, the creation of the Institute for Drugs and Drug Addiction (IDT), in 2002. In 2002, by Legal Decree no 269-A/2002, of 29th November, the Institute for Drugs and Drug Addiction (IDT) was created. The institute became extinct on 26th January 2012, when the publication of Legal Decree no 17/2012 in the Official Gazette, approving the Institutionalization Service for Addictive Behaviors and Addiction (SICAD).This is a central Ministry of Health service, directly integrated with State administration, although autonomously administered. The aim of the service is to encourage reducing the consumption of psycho-active substances, as well as preventing addictive behavior and decreasing addictions(8).

Brazil and Portugal – similarities and differences

Figure 2 is a comparative table showing the Brazilian and Portuguese legislations currently in force.

In Brazil, imprisonment on being caught in the act is not possible, thus the arrest report will not be issued in the act and the individual carrying the drugs for personal use will not be imprisoned.

The offender, a possible addict or user, should be referred immediately to the appropriate court. If there is no legal authority on duty, they should be arraigned to attend court in due course.

In the absence of a judge, then, the police authorities should draft the incident report and order expert examinations. After this stage, the suspect will undergo a forensic examination if necessary or if the police authority deems it appropriate, and then released.

Law no 9,099/1995 of the specialist criminal courts will be applied to the offender. At the hearing, the Public Ministry will propose a penal sentence, this being a type if agreement in which the responsibility, or otherwise, of the offender is not contested.

If the offender accepts the deal, their lawyer will need to be present. As responsibility is not contested, the penalties expressed in Law no 11,343/2006 will automatically be applied, that is, warning on the effects of drugs, community service and attending an educational program or course.

In Portugal, an individual caught with illegal drugs, providing it does not exceed the limit, will be sent to a Discussion Commission. Here, they will analyze whether the individual is an addict or a user, in order to determine the correct treatment. If addiction is identified, the individual will be invited to attend a treatment center. It should be emphasized that the consumer may refuse to accept treatment.

Law no 30/2000 does not legalize consumption of drugs, it decriminalizes it. Thus, the crime of consumption included in article 40 of Legal Decree no 15/93 became a contravention, i.e. an administrative violation. The consumer will be identified and if necessary searched and if found in possession of the substances will be referred to the appropriate committee.

The processing of the contraventions and applying the respective sanctions is the responsibility of an appointed drug deterrence committee. The possible executions of fines and alternative sanctions falls to the civil authorities.

The commission listens to the consumer, with all elements convened to make a judgment. Whether the individual is a drug addict or not, what substances he had consumed and in which circumstances, where he was found, his economic situation, in other words, a series of facts are analyzed.

At the consumer's request, a therapist of their choice or in whom they trust may participate in the process. The commission may propose or request appropriate medical examinations, such as blood or urine.

It is worth pointing out that this commission is a decision making body composed of three individuals, a lawyer, a psychologist and a social care worker, supported by a technical team.

To have voluntary treatment, the consumer may use either public or private services.

As mentioned above, if the individual is found to be an addict, he will be invited to attend a treatment center, and may accept or not, although if he does not accept and is later caught again, he will be subject to certain penalties.

The penalties can be found in Law no 30/32000, consisting of community work, being banned from certain places etc. Agreeing to treatment is, then, the most sensible option.

As for occasional users, this individual will be given the opportunity to discuss and analyze certain subjects related to how he lives his life, among other. Based on this, some are referred for treatment, as they are found to be addicted.

Some similarities and differences for those caught carrying illegal drugs for personal can be pointed out between the Brazilian and Portuguese legislation. The Brazilian Law identifies as user or addict whoever acquires, stores, possesses, transports or carries illegal drugs for personal use. In Portugal, an addict is someone who acquires or possesses for own use plants or substances included in the tables annexed to Legal Decree no 15/93, it being necessary to analyze whether the quantity of the substances is within average individual consumption for 10 days. In Brazil, Law no 11,343/2006 deals with users and addicts without presenting a specific quantity to characterize the addict. Drug consumption is considered a crime, being of a criminal nature. In Portugal, such consumption, depending on the amount, is not a crime, being of an administrative nature.

The goal, both in Portugal and in Brazil is for the addict to recover, along different paths. Although in Brazil consuming small quantities of drugs is a crime, whereas it is not considered to be so in Portugal, the main goal of both is to treat the addict and for them to recover.

It is impossible not to comment on the various data that appear concerning decriminalization of drug consumption in Portugal, that is, concerning the individual found consuming drugs. In relation to this material, news items stating that drug consumption in Portugal has increased, as have deaths related to drug consumption(9-10) stand out. Such statements contradict the analysis of the reports given in this study(11) and show the complexity of the problem of drug consumption.

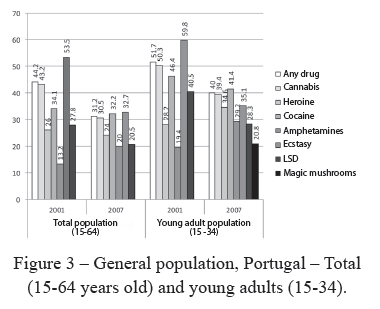

For example, Figure 3 shows the continuous rate of consumption according to type of drug for the Portuguese population overall and for young adults. It can be seen that there was a decrease in this rate between 2001 and 2007 in the young adult population (15-34 years old) compared with the population aged between 15 and 64, where the decrease was still greater.

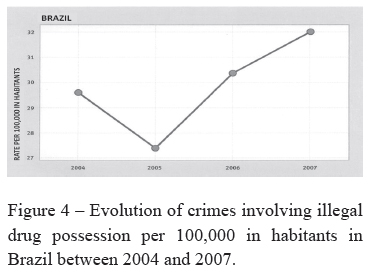

Brazil also has data on combatting drugs that confirm the obstacles to decreasing dealing and use of narcotics, even with Law no 11.343/2006(12). The report in the II Household Survey On the Use of Psychotropic Drugs in Brazil, from 2005, and the Brazilian Drug Report both indicate an increase in drug-related crime in Brazil(13), as shown in Figure 4 (Sergipe is not included, Rio Grande do Sul, is not included in 2005 and 2007, and Paraná, is not in 2007).

The references cited are the most up-to-date found on public websites. In this context, it is important to make mention of some of the plans to tackle drugs in Brazil, the aim of which is to reduce the numbers shown in the above mentioned report, such as actions against crack consumption, with the aim of caring for drug addicts and their families, combatting dealing and preventing drug use(14). Projects and actions such as the Police Pacification Units were also created in order to recover territory occupied by drug dealers.

Final Considerations

There are some similarities in treatment given to users and addicts in Brazil and in Portugal, although in Brazil, legally, drug use continues to be a crime. Both national systems treat dealers rigorously and are concerned with drug users and addicts.

In Portugal, an individual caught consuming drugs is taken before a commission the members of which are trained to identify users' problems and subject them to treatment. In Brazil, an individual caught carrying drugs for personal use is taken before a Special Criminal Court or, if not possible, taken to the Police Station and the legal process is followed. After this procedure, the addict or user is warned about the effects of drugs, sentenced to community service or educational measures by attending an educational course or program. The judge may decide for the Authorities to provide the offender with free treatment at a health care establishment, preferably on an outpatient basis.

In spite of the legal modifications presented in this study and of the introduction of different public policies relating to drugs, Brazil still focuses on the use of drugs in the paradigm of public safety, not prioritizing more effective actions of public health caring for the drug user or addict from a multi-dimensional perspective. Even those compulsory institutionalizations remove addicts from the streets, a more humane and effective solution remains to be found.

Thus, the experience of Portugal may bring interesting elements to constructing a Brazilian model that considers the historical evolution of drugs in this country, influences of different internal and external levels of power, the complexity of the phenomenon and the need to combine political, economic, social and cultural variables in designing legislation and public policies and considering, above all, the interfaces with public safety and health.

References

1. Gomes LF, Cunha RS, Bianchini, A. Nova lei de drogas comentada: artigo por artigo: lei 11.343, de 23.08.2006. 3ª ed. São Paulo (SP): Editora Revista dos Tribunais; 2008. 3278 p. [ Links ]

2. Governo Federal do Brasil. [Internet]. Saúde amplia assistência a dependentes químicos. [acesso 31 jul 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.brasil.gov.br/enfrentandoocrack/noticias/saúde-amplia-assistencia-a-dependentes-quimicos. [ Links ]

3. Justiça proíbe PM de expulsar usuários da cracolândia. Jornal Estadão [Internet]. [acesso 31 jul 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.estadao.com.br/noticia_imp.php?req=geral,justica-proibe-pm-de-expulsar-usuarios-da-cracolandia,908759,0.htm [ Links ]

4. STF decide que suspeito de tráfico pode responder em liberdade. Folha de São Paulo [Internet]. [acesso 28 maio 2012]. Disponível em: http://folha.com/no1088618. [ Links ]

5. Comissão sugere descriminalizar uso e plantio de drogas. Jornal Folha de São Paulo [Internet]. [acesso 28 maio 2012]. Disponível em: http://folha.com/no1096760. [ Links ]

6. Justiça ordena a 1ª internação compulsória. Folha de São Paulo [Internet]. [acesso 24 de janeiro de 2013. Disponível em: HTTP://abp.org.br/abp/internacao_compulsoria_folha.pdf [ Links ]

7. Comunidade Segura [Internet]. [acesso 27 abr 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.comunidadesegura.org/fr/pint/43391 [ Links ]

8. Instituto da Droga e da Toxicodependência (PT). Relatórios [Internet]. [acesso 27 abr 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.idt.pt/PT/IDT/Paginas/MissaoVisao.aspx [ Links ]

9. Consumo de droga está a aumentar em Portugal. Jornal de Notícias. [Internet]. [acesso 25 jul 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.jn.pt/common/print.aspx?content_id=1043066 [ Links ]

10. Informação online. [Internet]. Mortes por consumo de droga em Portugal subiram 45%, mas número é inflacionado. [acesso 25 jul 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.ionline.pt/conteudo/31402-mortes-consumo-droga-em-portugal-subiram-45 [ Links ]

11. Ato do Senado autoriza pena alternativa para tráfico. Consultor Jurídico [Internet]. [acesso 6 jun 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.conjur.com.br/2012-fev-22/senado-risca-expressao-proibe-pena-alternativa-lei-drogas?imprimir=1. [ Links ]

12. Observatório Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas. [Internet]. II Levantamento Domiciliar Sobre o Uso de Drogas Psicotrópicas no Brasil – 2005. [acesso 23 mar 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.obid.senad.gov.br/portais/OBID/index.php. [ Links ]

13. Duarte PCAR, Stempliuk VA, Barroso LP (orgs.). Relatório Brasileiro Sobre Drogas [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas, 2009. [acesso 23 mar 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.obid.senad.gov.br/portais/OBID/biblioteca/documentos/Relatorios/328379.pdf [ Links ]

14.

Governo Federal do Brasil. [Internet]. Enfrentando o Crack. [acesso 23 mar

2012]. Disponível em: http://www.brasil.gov.br/enfrentandoocrack/publicações/crack-e-possivel-vencer-1. [ Links ]

Received: Apr. 9th 2013![]() Correspondence

Correspondence

Carla Aparecida Arena Ventura

Universidade de São Paulo. Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto

Departamento de Enfermagem Psiquiátrica e Ciências Humanas

Av. Bandeirantes, 3900

Bairro: Monte Alegre

CEP: 14040-902, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasi

E-mail: caaventu@gmail.com

Accepted: Apr. 22nd 2014

texto em

texto em