Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

versão On-line ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.17 no.3 Ribeirão Preto jul./set. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.smad.2021.163560

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sociodemographic and clinical profile of users of psychoactive substances in an accredited philanthropic hospital*

Jaqueline Fátima de Souza ; Marcos Hirata Soares

; Marcos Hirata Soares ; Jessica Andrade Tiziani

; Jessica Andrade Tiziani

Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Pós Graduação, Londrina, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: to describe the profile of users of psychoactive substances, their outcomes and clinical complications.

METHOD: a cross-sectional study with 67 patients in an accredited philanthropic general hospital. Exploratory descriptive analysis based on data obtained with the addiction severity index - 6 and the Alcohol Smoking Substance and Involvement Screening Test.

RESULTS: there was predominance of males in 83.5% of the causes of admission, 32.8% were related to the musculoskeletal system, and 43.3% of the patients were unaware of previous comorbidities. Prevalence of 73.7% of alcohol abuse, 44.8% scored higher than 27 points, indicating the need for referral to the psychiatric specialty.

CONCLUSION: efforts are needed to improve and mature processes to ensure the quality of service and patient safety in involvement with psychoactive substances in a philanthropic general hospital.

Descriptors: Alcoholism; Illicit Drugs; General Hospital; Mental Health.

Introduction

Historically, the psychiatric reform has been marked by implementations of services that adhere to the psychosocial care model, in which the Psychosocial Care Centers (Centros de Atenção Psicossocial, CAPS) have started to play a fundamental role centered on mental health care(1). However, several challenges are faced in the context of the psychiatric reform, mainly the integration of non-specialized services in mental health. Common sense still understands that psychological suffering, in a way, is irrational, which suggests that the asylum model would be the most appropriate(2), contrary to the assumption in the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS)(3).

The general hospitals of medium and high complexity started, then, the integration of the Psychosocial Care Network (Rede de Atenção Psicossocial, RAPS), by means of Ordinance No. 3,088/2011, proposing comprehensive care services and enabling the performance of professionals with specific training as they governed by the SUS principles and guidelines(4-5).

Hospital services incessantly receive patients at risk of death from alcohol and drug abuse. Alcohol abuse, specifically, was only recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a mental illness since 1977. Since then, the WHO considers that 10% to 12% of the world population has problems with alcohol abuse, also associated with socioeconomic factors(4).

According to the World Drug Report, there was a 39% increase in drug consumption between the years 2001 and 2015, increasing by 60% the causes of deaths in the world, having as main characteristic the prevalence of higher consumption among men. In Brazil, nearly 3% of the general population suffers from mental disorders and, in 6% of this population, the disorder presented is related to the abuse of alcohol and other drugs, of which 12% need continuous care related to mental disorders(5).

The evidence currently found in the Brazilian population points out that, from the total population with mental disorders, 6% to 8% are related to alcohol abuse(6). Although there is vast literature addressing the characterization of this population, there is scarcity of studies in accredited philanthropic hospitals that aim at patient safety based on goals and indicators for evaluating multi-professional care, including specialized assessments for mental health and its clinical outcome when necessary.

Thus, the objective was to describe the socioeconomic profile of users of alcohol and other drugs admitted to an accredited general hospital, as well as the outcome of their clinical complications after their hospitalization.

Method

This is a cross-sectional study, carried out in a general philanthropic hospital accredited by the National Accreditation Organization (Organização Nacional de Acreditação, ONA), in southern Brazil. This hospital has 338 beds, but no psychiatric beds. The survey took place between November 2018 and April 2019. The sample was non-probabilistic for convenience, so it was intentional occurring when selecting the service in a student training institution.

For inclusion in the sample, patients over 18 years old, hospitalized for more than 24 hours, with a history of alcohol or other drug use, of both genders and with any disease or clinical condition were selected, with a pre-established association with psychoactive substance abuse. Patients diagnosed with severe mental disorder, individuals with physical deterioration, language limitations and/or intoxication that limited the application of the guiding instrument were excluded. Among these, from the consultation of the electronic medical record, 22 patients were excluded, nine of whom did not show improvement in their clinical conditions, and nine died before the first evaluation. After the researcher's verbal invitation, two did not accept to participate and another two requested discharge before the verbal invitation. An active search was carried out in inpatient and intensive care units. When approaching each subject, the objective and conditions of the research, which involved the application of the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF) and, sequentially, of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI6).

For data collection, the ASSIST test was used, which was validated in Brazil(7), which aims to identify problems related to the use of alcohol and psychoactive substances, by means of a total score between zero and > 27 points. Reliability was achieved through test-retest using the Kappa coefficients, which ranged between 0.58 and 0.90.

The ASI6 scale translated and validated in 2005 was designed to obtain information related to the socioeconomic-demographic and cultural aspects associated with the abuse of alcohol and other drugs. This scale contains eight axes for the individual's psychosocial understanding. For this study, the following approaches were used: gender, age group, race, marital status, income, source of income, schooling, dependents of income, and formal contract. The ASI6 scale had reliability through test-retest; for the subscales, Cronbach's alpha was used, which ranged from 0.64 to 0.95(8).

In addition to the application of the instruments, data was collected from the electronic medical record, with information on the period of hospitalization and assistance provided by the professionals: psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, among other specific medical specialties for clinical treatment. For data analysis, exploratory statistical analysis was chosen, using measures of central tendency for the presentation of the variables. For the entire research process, the researcher received a 40-hour training to perform the Brief Intervention and apply the data collection instruments, while participating in the research group.

Results

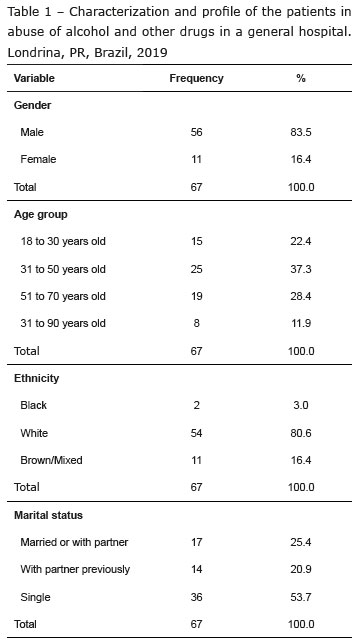

There was predominance of male hospitalizations in the general hospital, with 83.5% compared to female hospitalizations, which were 16.4% (Table 1). According to age, 37.3% are between 31 and 50 years old, preceded by 28.4% between 51 and 70 years old. Regarding marital status, there are 53.7% of single individuals, followed by 25.4% of married or living together. For the ethnicity variable, 80.6% declared themselves as white-skinned, 16.4% as brown-skinned and mixed race, and 3% as black-skinned.

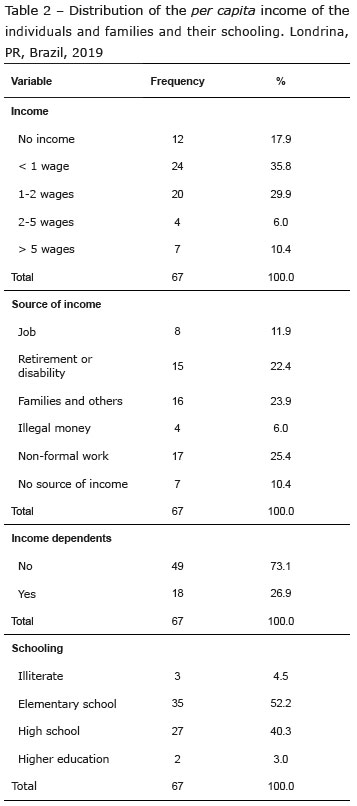

Regarding the per capita income (Table 2), 53.7% of these individuals survive on an income of up to two minimum wages, 17.9% have no monthly income, 25.4% have their source by informal jobs, and 62.9% did not have a formal contract. The survey also showed a low schooling index, in which 52.2% have only elementary education; a factor that may have influenced and hindered insertion in the job market, since 62.9% of the individuals had their last job without a formal contract. Regarding housing conditions, 26.3% reported having already lived in a supervised shelter.

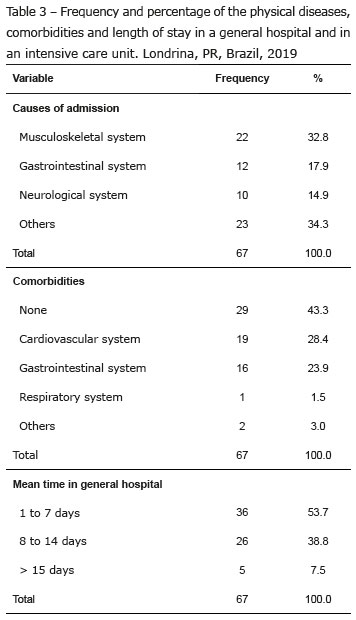

As for the clinical aspects, it was identified that 43.3% of the hospitalized patients had no comorbidities or diagnosis previously established. Of the individuals who had knowledge of comorbidities, there were 23.9% with diseases of the gastrointestinal system and, of these, 22.9% had alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Regarding diseases of the cardiovascular system, 28.4% developed arterial hypertension. However, 32.8% were hospitalized for the consequences of multiple fractures.

Among the other findings in this study, 17.9% of the patients were admitted due to changes in the gastrointestinal system, where the highest incidence was of liver disease and, with the same percentage, patients with neurological disorders (brain trauma and stroke) were admitted.

The mean length of stay (MLS) was one to seven days for 53.7% of the patients, and more than 15 days for 7.5% of them (Table 3). Considering that 13.4% of these inpatients needed an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and had a mean length of stay of six to seven days; when admitted to the ICU, they presented the Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 (SAPS 3 - validation and refinement of prognostic indexes in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU) filled out. Thus, 9.2% of these patients had a score below 20%, and 9.2% had a score between 21% and 40%. The degree of dependence of all the individuals, according to the Fugulin scale (classification of patients, according to the degree of dependence), 34.2% were classified as degree of dependence III, 30.1% as degree of dependence II, and 27.1% as degree of dependence IV.

Correlating the percentage of degree of dependence with the complication of the human body system, it was observed that the individuals hospitalized due to complications of the gastrointestinal system demanded more time for care and attention from the Nursing team when compared with the other complications of other body systems. Of these, 13.4% were classified as degree of dependence IV at some point during the hospitalization period. Those treated for complications of the musculoskeletal system had a mean percentage of 14.9%, with degree of dependence III.

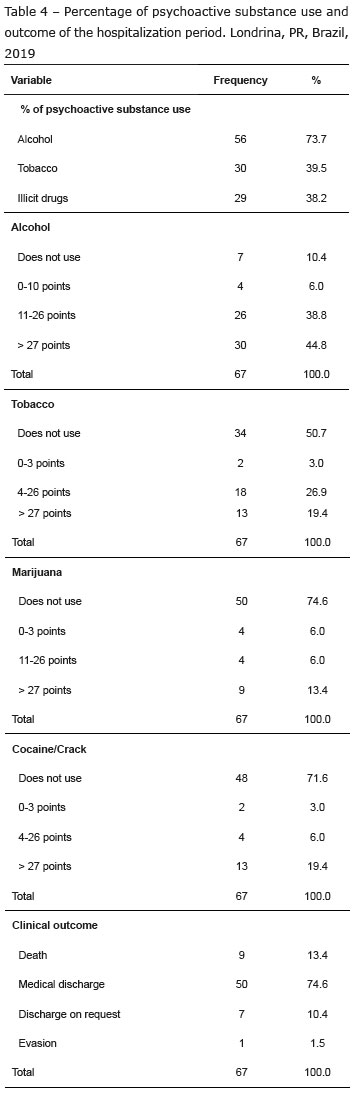

It was possible to verify that 73.7% of the subjects used alcohol, 38.8% had a score between 11 and 26 according to the ASSIST test, a score that indicates the need for a brief intervention; in addition, 44.8% of these had a score above 27 and needed to be referred for specific treatment. Of those surveyed, 39.9% also used tobacco, with 19.4% of the individuals having scores greater than 27. When assessing the use of illicit substances, 25.4% of the subjects were classified as probable marijuana addicts, 28.4% using cocaine/crack, and 72.6% made their first use of illicit drugs when they were between 10 and 17 years old, with 27.6% after 18 years old (Table 4).

Considering multi-professional care, 38.8% received care from a social worker, 9% from a psychologist, and 3% had inter-consultation with a psychiatrist, which results in 55.2% of the patients using psychoactive substances without receiving care in the psychosocial sphere.

As for the "use of psychoactive substance" variable, an individual could use more than one psychoactive substance, thus not allowing a percentage of 100%.

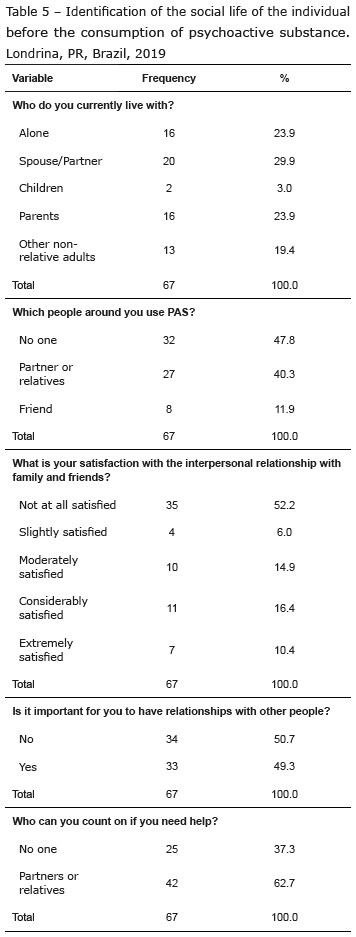

It is possible that adherence to treatment may have been influenced when the individuals returned to their social life, amid customary habits of PAS consumption, as well as it may have had an influence on their satisfaction with the relationship and the state of harmony in living together with family members and friends. According to Table 5, it was identified that 52.2% of the individuals have people around them who use PAS. Among these, 40.3% are family members and 11.9% are friends, who probably use PAS. Among these, 52.2% reported that they were not at all satisfied with their relationship with the people around them, 16.4% said they were moderately satisfied, and only 10.4% reported having an extremely satisfied family social life. In addition, 37.3% of the individuals state they cannot count on people in difficult times.

Family relationships and social interaction resulted in physical aggression for 44.8% of the individuals. For 71.6% of these, the first aggression suffered was at age below 10 years old, 19.7% suffered aggression between 11 and 20 years of age and, in only 5.3%, the aggression occurred at an age over 20 years old. Of the individuals who suffered physical aggression, 5.3% also suffered sexual aggression at some point in life, with 100% being female.

Discussion

Hospitalization for causes associated with the use of psychoactive substances is greater among the population in socioeconomic and educational vulnerability, meaning that public policies that favor social support must be implemented. These policies emerged with therapeutic planning, therapeutic integration, interaction between therapeutic consultations and emergencies and BI in Europe, contributing to the discussions on the trajectory of mental health in Brazil(9).

However, the comorbidities associated with the use of alcohol and tobacco are diseases of interest, especially for primary care professionals. However, it is a public health problem, given its high prevalence found in society in the last decades(10).

In this sense, the early diagnosis of diseases associated with the use of PAS in basic health units is of fundamental importance, through interviews conducted by trained professionals, who can use knowledge and techniques of Brief Intervention (BI) with public health programs(11). Furthermore, it was evidenced that 41.4% were unaware of any health problem previously, which corroborates the need for the BI practice to improve the prevention of the use and abuse of psychoactive substances.

However, it is common for psychoactive substance use disorders and comorbidities to be diagnosed in hospital institutions, when these patients are seen in emergency situations due to clinical complications. Thus, it is important for professionals with knowledge and training to offer quality care in mental health, enabling the use of the method for the application of the BI(12).

In the same objective of improving the quality of care provided, the National Organization for Hospital Accreditation (ONA) describes that hospital institutions accredited at level 1 must have procedures to assist patients who are victims of physical, moral and psychological aggression, abandonment and attempted suicide, as well as providing the patients and their families with support regarding socioeconomic issues and social reintegration. Thus, the importance is inferred of the performance of a multidisciplinary team with training in mental health to provide care to these individuals admitted to the hospital network(13).

However, multiple factors, such as dimensioning of personnel and costs of specialized medical care, can interfere in multi-professional care for individuals with mental health problems, whether in-hospital care or referral for rehabilitation.

The mean length of stay in people who abuse psychoactive substances has often increased on average, when associated with the socioeconomic difficulties, pointing out the difficulty of hospital discharge due to the sociodemographic factor, which has lack of income as direct impact. This fact also demonstrates the need for attention from the social service(14).

In this context, multiple factors can contribute to a mean length of stay, leading to delayed hospital discharge, namely related to the social services. Given this trend, three types of causes can directly interfere in the delay of hospital discharge: organizational or intra-hospital causes, such as weakness in the dimensioning of specialized professionals to manage the individual's complications in terms of mental health, such as the management and control of signs and symptoms of withdrawal; individual causes such as acceptance of the proposed treatment and this is related to the use of PAS, with the possibility of the individual being in the phase of pre-contemplation or contemplation; and community causes related to existing resources in the community for the care of the individual, where it does not always provide continuity and follow-up of the proposed treatment of mental health management(15).

Regarding the aforementioned organizational causes, multi-professional practice is of great importance, with a study carried out in England with 179 hospitals, of which 168 enjoyed psychiatric liaison services, 79% of which included at least one psychiatrist and a nurse specialized in mental health in the team, a team that provided care in all units of the hospital. However, the study does not report the percentage of care provided to the hospitalized individuals who needed care from the team. The main cause of admission to this study was self-mutilation (63%) caused by abuse of alcohol and other substances(16). The process of assisting the individual through a multi-professional team, in addition to promoting better human relations, aims to provide individualized, planned and effective treatment in all the biopsychosocial aspects and needs of the individual(13).

For a while, inter-consultations were only requested among the medical professionals, which made the few requests for the mental health team to be evident. In this new hospital environment, where multi-professional enhancement took place, other professionals also began to request evaluations and consultations to the individuals eligible for treatment in mental health, including those who abuse psychoactive substances(17).

Not being different in this research, inter-consultation was requested only by the medical professional for some time, over the years and the implementation of the patient safety process requests for inter-consultation can be made by any health professional to the psychologist, service professional social and Nursing team; for the request of the psychiatrist, a physician to physician request is also necessary, due to document and billing issues of the financial audit.

In the present study it was observed that the inter-consultations were minimally requested to the professional specialized in mental health; it was considered that the individual sought hospital help due to issues of clinical complications or traumas, so care was performed by the specific professional of the organic complication found. The psychological and/or psychiatric alterations they presented, either due to abstinence or to excessive use of the PAS, were treated by the medical professional responsible for the primary hospitalization; when this compromised the clinical treatment, specific care and social services were requested to schedule the discharge for continuity after hospital discharge.

In another study carried out in Lisbon, the percentage of inter-consultations with specialists in mental health was also assessed, finding requests for inter-consultation for 750 patients during five years. It was identified that 25% of these requests were due to depression and 19% to psychomotor agitation, considering acute organic mental disorders, and 60% of the patients had no previous follow-up in psychiatry(18).

However, inter-consultations for mental health care are not always well accepted in the general services. A study carried out in Poland suggested that only 16% of the psychiatrists have clinical interaction with the other specialists available at the general hospital(19).

Corroborating with the research studies already carried out, this study also observed the fragility for an effective hospital discharge for cases in which the individual needed support from the municipality for the continuity of mental health treatment, since it does not cover and does not provide immediate care after discharge, with the institution's social service having difficulty optimizing hospital discharge.

Adding to the fact that there is difficulty in discharge, the hospital also has discontinuity of care as a factor, resulting in insufficient services and professionals in the public psychiatric service network for referring patients to the specialized service(20). In the researched institution, there was a weakness in the inter-consultation request process, since the availability of the psychiatric medical professional on duty was not evidenced, as well as in the data collected via the system presented in the results regarding the expert evaluation. What we can ask that contributed to the increase in the mean length of stay in the ICUs and in the hospitalization sectors.

In a study carried out with four groups, 31 individuals, it was observed that the search for help occurred from the installation of chemical dependence or because these individuals lost something significant in their life, in which the user went through hospital admissions due to complications(21), as well as it is known that the use of PAS is associated with the development of comorbidities and propensity to violent crimes, leading to emphasize the need for interdisciplinary care to the PAS users, since they are vulnerable to socio-economic, cultural and family problems(22), as has been debated by managers, researchers and social policy operators. In Brazil, this debate can be exemplified by an integrative review based on the question "What are the vulnerability indicators related to the social issue presented in scientific studies and how are they constructed?"(23).

In a study with 29 cases, which were related to sentinel events, 93.3% of these resulted in hospitalization for chronic use of alcoholic beverages. Having a mean alcohol abuse of 20.8 years, 55.2% of these families had an addictive behavior to the use of psychoactive substances, with cases of more than 20 years of alcohol abuse. Only 10.3% of these families were not considered vulnerable in social issues such as unemployment, low schooling, and daily drug use, which allowed us to conclude that the use of PAS worsened the vulnerability conditions of the families(23).

In the scope of qualitative research, a survey was made of the perception of family members regarding changes in daily life, whether family and/or social, after the insertion of drug dependence. The reports showed that living with people dependent on psychoactive substances can trigger various types of feelings, emotions and expectations for a change through faith, as well as the feeling of fear(24).

In the religious and spiritual context, prayers, penances and fasts were methods used by family members as strategies to seek strength in God, with prayers being a way of approaching the superior strength to attain the necessary strength to resist daily adversities(25). The search for prayers and religious beliefs both by patients and family members at this time was evident during the research, both in search of comfort and "cure". They seek in prayer an internal strength to overcome the difficulties encountered at the moment.

The implications of the use of psychoactive substances mainly point to the use of alcohol in the family, which can influence the early use of illicit drugs, and can be in childhood or adolescence, as found in this research, that 40.3% of individuals live with family members who also use PAS, which contributes to the qualitative study conducted in the metropolitan region of Baixada Santista-SP, with crack users, which identified in the reports that the use of illicit drugs beginning in adolescence occurred with consent or sharing of the parents themselves. Also highlighting the parents' aggressive and violent behavior, with the father being the biggest aggressor when under the influence of drugs(26).

A study pointed out that, among several factors of early drug use, from the perspective of the crack user, the fragility of family bonds stands out, with the presence of domestic violence in childhood, conflicts, affective losses, separation of parental figures, and the use of alcohol or other illicit drugs among family members around them. In 2009, the presence of childhood violence associated with the use of PAS was also assessed, identifying many who did not consider aggression as an act of violence, as it is a common practice and culturally accepted as an educational practice(26-27).

From the aforementioned studies, we can infer that values, cultural issues, family composition and social interaction interfere in affective relationships, with domestic violence being the most relevant and impacting factor to early influence the individual on the use of PAS, making family and social harmony difficult, which reinforces for this study that it was identified that 44.8% of the individuals suffered physical aggression at some point in their life and, of these, 71% even as a child under 10 years old, with 52.2% of the total surveyed living together at the moment with other family members who also use PAS.

Establishing a relationship of trust and mental health care between family members and PAS users is a goal yet to be achieved by the professionals, since health needs are still linked to physical health, as what does not manifest through signs and symptoms is not always recognized as a need(28). This exposition shows us the lack of awareness of the diseases that affect behavior and mental health.

This author also corroborates that living with illicit drug addicts, such as crack, is even more difficult when harms to the family are frequent, such as the sale of their own belongings and family members in search of income to maintain their addiction, even leading to risks arising from theft. The use of the substance causes the family members to distance each day, as it does not allow for a reciprocal relationship, leading to the loss of bonds(26-29).

A qualitative research study with family members surveyed reports and perceptions that some facts, such as the existence of an important person for the individual, can be motivational for at least the PAS dependent trying to remain abstinent. There were also reports of moments of positive affection and fun in family life that allowed relapse to drug use, as well as negative affections(24). This context gives us in the research in question that 40.3% of the patients are supported by family members who also use psychoactive substances, and that 47.8% of the people around them do not use any substance, which suggests that they will have greater motivation to stay abstinent.

The search for social acknowledgment that PAS abuse should be considered as a disease and not as a moral state is inexhaustible, as is the search for improving quality of care for these individuals.

This study identified the social exclusion of PAS users, who at some point were exposed to the situation of vulnerability and possible situations of violence. Therefore, it will be important and necessary to restore the State's ethical commitment to the protective principles for these people, proposing the evolution and adaptation of welcoming strategies to the individual and specialized training of the professionals.

It corroborates with a qualitative study carried out in a health unit even though it aimed to evaluate the teaching and learning method in professional training and in the training in health institutions, concluding that, through active methodologies, the learning of the employees shows more effective having a greater positive result when training is carried out continuously(30) .

Conclusion

The search for help and hospital care shows us the fragility of the body first, where they seek to cure pain. However, we are faced with the need for concomitant mental health care for the use of PAS, which requires an active specialized team, which was not found in this research scenario, due to the fragility in the request for consultation and the number of professionals not compatible with the demand.

This evaluation of specialized professionals in mental health is also not carried out in due proportion, since there may be interference with the SUS funding cost, not able to financially provide the provision of services by professionals specializing in mental health, despite guidance from the ONA, as a requirement for quality and safety management, so that the individuals who are victims of physical, moral and psychological aggression, abandonment and attempted suicide receive care, given that 44.8% of the individuals using alcohol scored more than 27 points, therefore requiring referral to the specialized care service for mental health rehabilitation. These costs will be detailed later in another study.

Further research studies are needed on this theme, with the aim of evaluating the outcome and its clinical complications after the implementation of strategies, such as inter-consultation and multidisciplinary mental health monitoring, in order to minimize hospital stay and costs.

References

1. Amarante P, Torre EHG. Madness and cultural diversity: innovation and rupture in experiences of art and culture from Psychiatric Reform and the field of Mental Health in Brazil. Interface. 2017;21(63):763-74. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0881 [ Links ]

2. Nascimento LR. Reforma psiquiátrica brasileira [dissertação]. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás; 2018. [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: WHO; 2018. [ Links ]

4. Portaria nº 3.088, de 23 de dezembro de 2011 (BR). Institui a Rede de Atenção Psicossocial para pessoas com sofrimento ou transtorno mental e com necessidades decorrentes do uso de crack, álcool e outras drogas, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da União. [internet]. 26 dez 2011. [Acesso 8 out 2019]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/29zD847 [ Links ]

5. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Direitos humanos e saúde mental. [Internet]. 2014 Nov 27 [Acesso 27 nov 2014]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/2nrylOa [ Links ]

6. Pacheco AM, Silva RDMS, Ramos MC. Designing a health care work flow for alcohol and drug addiction. Rev Bras Pesqui Saúde. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Oct 8];19(1):21-7. Available from: http://periodicos.ufes.br/RBPS/article/download/17712/12138 [ Links ]

7. Henrique IFS, De Micheli D, Lacerda RB, Lacerda LA, Formigoni MLOS. Validação da versão Brasileira do teste de triagem do envolvimento com álcool, cigarro e outras substâncias (ASSIST). Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2004;50(2):199-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302004000200039 [ Links ]

8. Gorenstein C, Yuan-Pang W, Hungerbühler I, compiladores. Instrumentos de Avaliação em Saúde Mental. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2016. 500 p. [ Links ]

9. Botega NJ. Prática psiquiátrica no hospital geral: interconsulta e emergência. 4.ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2017. [ Links ]

10. World Health Organization. Substance Abuse Department. Global status report: alcohol policy. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Acesso 1 out 2020]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/gsrah/en/ [ Links ]

11. Abreu AMM, Jomar RT, Taets GGC, Souza MHN, Fernandes DB. Screening and brief intervention for the use of alcohol and other drugs. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(Suppl 5):2258-63. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0444 [ Links ]

12. Jaworowski S, Raveh-Brawer D, Gropp C, Haber PS, Golmard JL, Mergui J. Alcohol related harm: knowledge assessment of medical and nursing staff in a general hospital. Isr J Psychiatry. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Oct 8];55(2):32-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30351278 [ Links ]

13. Organização Nacional de Acreditação (BR). Manual das Organizações Prestadoras de Serviço em Saúde. São Paulo: Organização Nacional de Acreditação; 2018. 152 p. [ Links ]

14. Baeza FL, Rocha NS, Fleck MP. Predictors of length of stay in an acute psychiatric inpatient facility in a general hospital: a prospective study. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2018;40(1):89-96. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2016-2155 [ Links ]

15. Modas DAS, Nunes EMGT, Charepe, ZB. Causas de atraso na alta hospitalar no cliente adulto: scoping review. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2019;40:e20180130. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2019.20180130 [ Links ]

16. Walker A, Barrett JR, Lee W, West RM, Guthrie E, Trigwell P, et al. Organisation and delivery of liaison psychiatry services in general hospitals in England: results of a national survey. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e023091. doi: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023091 [ Links ]

17. Paula BHB. Estudo das relações interprofissionais no hospital geral: contribuições da saúde mental para uma clínica do sujeito [dissertação]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2016. [ Links ]

18. Silva IC, Lopes J. 5 anos de psiquiatria de ligação no Hospital Vila Franca de Xira. Rev Psiquiatr Consil Ligac. [Internet]. 2019 [Acesso 8 out 2019];26(1):1-4. Available from: https://bit.ly/2osdomR [ Links ]

19. Chojnowski J, Załuska M. Psychiatric wards in general hospitals: the opinions of psychiatrists employed there. Psychiatr Pol. 2016;50(2):431-43. doi: http://doi.org/10.12740/PP/35378 [ Links ]

20. Andrade ACM, Otani MAP, Higa EFR, Marin MJS, Caputo VG. Multiprofessional care in a psychiatric unit of general hospital. Rev Psicol Diversidade Saúde. 2018;7(1):60-71. doi: http://doi.org/10.17267/2317-3394rpds.v7i1.1846 [ Links ]

21. Azevedo CF. Manejo do uso abusivo de álcool e outras drogas na perspectiva da entrevista motivacional [dissertação]. Goiânia: Universidade Federal de Goiás; 2015. [ Links ]

22. Claro HG, Oliveira MAF, Titus JC, Fernandes IFAL, Pinho PH, Tarifa RR. Drug use, mental health and problems related to crime and violence: cross-sectional study. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2015;23(6):1173-80. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.0478.2663 [ Links ]

23. Schumann LA, Moura LB. Vulnerability synthetic indices: a literature integrative review. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20(7):2105-20. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015207.10742014 [ Links ]

24. Rodrigues TFCS. Feelings of families regarding drug dependence: in the light of comprehensive sociology. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(Suppl 5):2272-9. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0150 [ Links ]

25. Claus MIS, Zerbetto SR, Gonçalves AMS, Galon T, Andrade LGZ, Oliveira FC. The family strengths in the context of psychoactive substance dependence. Esc Anna Nery. 2018;22(4):e20180180. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2018-0180 [ Links ]

26. Barros NA, Tucci AM. Perceptions of crack users on their family relationships in childhood and adolescence. Psicol Teoria Pesqui. 2018;34:e34419. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e34418 [ Links ]

27. Dunlap E, Golub A, Johnson BD, Benoit E. Normalization of violence: experiences of childhood abuse by inner-city crack users. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2009;8(1):15-34. doi: http://doi.org/10.1080/15332640802683359 [ Links ]

28. Lima DWC, Leite ACQB, Vieira AN, Leite AR, Luis MAV, Azevedo LDS, et al. Necessidades de saúde de familiares de usuários de substâncias psicoativas. Rev Eletron Enferm. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Oct 8];20:v20a12. doi: http://doi.org/10.5216/ree.v20.47410 [ Links ]

29. Siqueira DF. Familiar do usuário de substâncias psicoativas: revisão de literatura. Universidade Regional Integrada do Alto Uruguai e das Missões - Campus Santiago. 2018. [Acesso 1 out 2020]. Disponível m: http://www.urisantiago.br/multicienciaonline/adm/upload/v3/n5/02fe22060bbb9f546f81229f7228e6f9.pdf [ Links ]

30. Fernandes MA, Soares NSA, Ribeiro ÍAP, Sousa CCMS, Ribeiro HKP. Active methodologies as a tool for training in mental health. Rev Enferm UFPE on line. 2018;12(12):3172-80. doi: http://doi.org/10.5205/1981-8963-v12i12a237762p3172-3180-2018 [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

Jaqueline Fátima de Souza

E-mail: jaquef.souzajp@gmail.com

Received: Oct 26th 2019

Accepted: Sep 30th 2020

Author's contribution

Study concept and design: Jaqueline Fátima de Souza.

Obtaining data: Jessica Andrade Tiziani.

Critical review of the manuscript as to its relevant intellectual content: Marcos Hirata Soares.

All authors approved the final version of the text.

Conflict of interest: the authors have declared that there is no conflict of interest.

* The publication of this article in the Thematic Series "Human Resources in Health and Nursing" is part of Activity 2.2 of Reference Term 2 of the PAHO/WHO Collaborating Centre for Nursing Research Development, Brazil. Paper extracted from master's thesis "Patient Care With Abuse of Psychoactive Substances in a General Hospital", presented to Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, PR, Brazil.

texto em

texto em