Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

versão On-line ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.17 no.4 Ribeirão Preto out./dez. 2021

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.smad.2021.176976

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Saúde mental na Atenção Primária: (des)encontros entre enfermeiros e pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia*

Salud mental en Atención Primaria: (des)encuentros entre enfermeros y pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia

Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa ; Daiane Márcia de Lima

; Daiane Márcia de Lima ; Rodrigo Sanches Peres

; Rodrigo Sanches Peres

Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brasil

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: compreender o imaginário coletivo sobre pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia por parte de enfermeiros inseridos na Atenção Primária, com foco em suas possíveis reverberações no tocante à atenção em saúde mental.

MÉTODO: pesquisa qualitativa, orientada pelo método investigativo psicanalítico, desenvolvida junto a 15 enfermeiros. O instrumento utilizado foi o Procedimento de Desenho-Estória com Tema, e os dados coletados foram interpretados psicanaliticamente visando à captação dos campos de sentido.

RESULTADOS: no imaginário coletivo da maioria dos participantes, ocupa lugar central a crença de que o acompanhamento de pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia é responsabilidade exclusiva de profissionais e/ou serviços de saúde "especializados", o que aparentemente atravessa, de modo marcante, os (des)encontros que se estabelecem entre os enfermeiros e os referidos pacientes.

CONCLUSÃO: essa crença é incompatível com os preceitos da Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira e com o papel a ser desempenhado, na Atenção Primária, pelos enfermeiros.

Descritores: Saúde Mental; Atenção Primária à Saúde; Relações Enfermeiro-Paciente; Esquizofrenia; Preconceito.

RESUMEN

OBJETIVO: comprender el imaginario colectivo sobre pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia por parte de enfermeros de la Atención Primaria, enfocándose en sus posibles reverberaciones con respecto a la atención en salud mental.

MÉTODO: investigación cualitativa, orientada por el método investigativo psicoanalítico, desarrollada con 15 enfermeros. El instrumento utilizado fue el Procedimiento de Dibujo-Cuentos con Tema, y los datos fueron interpretados psicoanalíticamente para capturar campos de sentido.

RESULTADOS: en el imaginario colectivo de la mayoría de los participantes, es central la creencia de que la continuidad de la asistencia a pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia es responsabilidad exclusiva de profesionales y/o servicios de salud "especializados", lo que aparentemente afecta de manera significativa los (des)encuentros que se establecen entre los enfermeros y esos pacientes.

CONCLUSIÓN: esta creencia es incompatible con los preceptos de la Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileña y con el papel que deben desempeñar los enfermeros en la Atención Primaria.

Descriptores: Salud Mental; Atención Primaria de Salud; Relaciones Enfermero-Paciente; Esquizofrenia; Prejuicio.

Introdução

O Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), pautando-se nos princípios da universalidade, da integralidade e da equidade, propõe-se a viabilizar o acesso aos serviços de saúde para todos os cidadãos e a oferecer um conjunto articulado e contínuo de ações de saúde em consonância com as necessidades de cada caso, fazendo-o sem preconceitos ou privilégios de qualquer espécie(1). A criação do Programa Saúde da Família (PSF) favoreceu a efetivação desses princípios mediante a reorientação do fluxo assistencial a partir da Atenção Primária e vem contribuindo para a consolidação da Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira ao fomentar a transição do modelo asilar para o modelo comunitário(2-3).

Isso ocorreu, basicamente, em virtude de dois motivos. Em primeiro lugar, porque a Atenção Primária se afigura como o nível de atenção em saúde que proporciona o contato inicial com o sistema de saúde e visa à promoção, à manutenção e à recuperação da saúde(4). Em segundo lugar, porque um dos objetivos básicos da Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira é a valorização da territorialidade nas ações de saúde mental, em respeito às singularidades de cada paciente(5). Ressalte-se que a noção de territorialidade abarca as relações políticas, econômicas, culturais e afetivas que advêm em espaços concretos como resultado da vida em sociedade(6). Além disso, é interessante sublinhar que, somando-se à criação do PSF, diversos outros marcos legais relativos às políticas públicas de saúde têm reforçado o valor da Atenção Primária para a reestruturação da atenção em saúde mental no país.

Nessa conjuntura, os enfermeiros têm um papel crucial a desempenhar, como interlocutores e catalisadores de programas voltados à saúde coletiva(7), visto que se ocupam tanto da administração e da organização dos serviços de saúde quanto da realização de práticas clínicas. Logo, tornou-se necessária a incorporação, ao trabalho dos enfermeiros que atuam na Atenção Primária, das chamadas "tecnologias leves", ou seja, das estratégias e das técnicas voltadas às relações em prol dos processos de produção de saúde, dentre as quais o acolhimento(8). Deve-se esclarecer que o acolhimento é enquadrado, pelo Ministério da Saúde(9), como uma ferramenta indispensável à construção do vínculo com qualquer paciente, de modo que representa uma diretriz da humanização da assistência.

Contudo, algumas pesquisas nacionais demonstraram que os enfermeiros que atuam na Atenção Primária, a despeito de sua relevância para a atenção em saúde mental, muitas vezes se limitam a proceder automaticamente ao encaminhamento de pessoas em sofrimento psíquico para profissionais e/ou serviços de saúde "especializados", ao invés de acolhê-las, desacreditando o exercício da autonomia e desvalorizando a territorialidade(10-12). Tais pesquisas ainda deixaram subentendido que, ao menos em parte, o referido fato deriva de estereótipos e preconceitos ancorados em crenças socialmente compartilhadas acerca da "loucura". Afinal, sinalizaram que pessoas em sofrimento psíquico tendem a ser taxadas - inclusive por profissionais de saúde - como desviantes, anormais, perigosas e disfuncionais, e, consequentemente, seriam passíveis de intervenções de cunho normativo e viés individualista.

A exploração do imaginário coletivo, em sua acepção psicanalítica, é capaz de fornecer elementos proveitosos para a demarcação de crenças dessa natureza(13). Ocorre que o imaginário coletivo vem sendo concebido, à luz da Psicanálise, como o substrato ideativo-emocional não consciente dos encontros que se estabelecem entre diferentes grupos sociais(14), pois engloba um conjunto de manifestações humanas que, mediante múltiplas modalidades expressivas, configura uma espécie de lugar existencial habitado por indivíduos e coletivos(15). O conceito psicanalítico de imaginário coletivo, assim, tem norteado uma ampla gama de pesquisas recentes, as quais, com recortes temáticos distintos, lançaram luz sobre elementos essenciais das subjetividades grupais(13-19).

Nenhuma dessas pesquisas, no entanto, investigou o imaginário coletivo de enfermeiros quanto a pacientes em sofrimento psíquico grave, em que pese a pertinência do assunto. E é válido acrescentar que pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia tendem a vivenciar um sofrimento psíquico especialmente acentuado por tratar-se de um transtorno mental cujos sintomas, prejudicando o funcionamento afetivo, social, familiar e profissional, podem ser altamente debilitantes(20). Diante do exposto, este estudo teve como objetivo compreender o imaginário coletivo sobre pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia por parte de um grupo de enfermeiros inseridos na Atenção Primária, com foco em suas possíveis reverberações no tocante à atenção em saúde mental. O referido foco, inclusive, sustenta a circunscrição deste estudo como um recorte de uma pesquisa desenvolvida com objetivos mais abrangentes.

Método

A exemplo de outras pesquisas que tematizam o imaginário coletivo(13-19), este estudo enquadra-se como uma pesquisa qualitativa orientada pelo método investigativo psicanalítico, o qual pode ser desenvolvido dentro ou fora de settings de atendimento clínico e se diferencia pelo emprego de estratégias metodológicas oriundas da Psicanálise com vistas à produção de conhecimentos científicos em torno de uma variedade de questões humanas(21). Ressalte-se que a Psicanálise, além de uma prática terapêutica e um sistema teórico, também se afigura como um método investigativo(22), especificamente de caráter construtivo-interpretativo.

O cenário deste estudo foi constituído pelos serviços de saúde da Atenção Primária de um dos quatro distritos sanitários de um município do interior de Minas Gerais. Tal distrito sanitário foi selecionado devido à facilidade de acesso pelos pesquisadores, sendo que, quando da coleta de dados, agregava 21 enfermeiros. Todos eles foram convidados a participar deste estudo, mas houve seis recusas. Dessa forma, os participantes foram 15 enfermeiros em atividade na Atenção Primária, os quais - como é comum em pesquisas qualitativas - compuseram uma amostra de conveniência, pois não foram selecionados com base em critérios estatísticos. A faixa etária deles variou dos 28 aos 60 anos e a experiência como enfermeiro variou de um a 16 anos, sendo que 14 eram do sexo feminino.

O instrumento utilizado neste estudo foi o Procedimento de Desenho-Estória com Tema (PDE-T)(23), o qual vem sendo amplamente adotado em pesquisas psicanalíticas sobre o imaginário coletivo(14-18). Por seu caráter lúdico, tal instrumento é capaz de facilitar a comunicação emocional mediante a constituição de um campo relacional entre o pesquisador e os participantes(24). Basicamente, quando do emprego do PDE-T, solicita-se, a cada participante, a elaboração de um desenho com um tema previamente definido pelo pesquisador em função do objetivo da pesquisa e, na sequência, a criação de uma estória sobre o desenho e de um título para a estória.

Neste estudo, o PDE-T foi utilizado individualmente, porém, em um contexto coletivo, durante o intervalo de uma reunião na qual os participantes estavam presentes, em um momento destinado especificamente para tanto. Ou seja, cada um deles realizou a atividade de maneira separada dentro do grupo em que se encontrava inserido, em consonância com a abordagem utilizada em pesquisas prévias(14,16). Os participantes foram solicitados a desenhar um paciente com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia sendo atendido por um enfermeiro na Atenção Primária, a redigir, no verso da folha de papel, uma pequena estória sobre o desenho e, por fim, a dar-lhe um título, bem como a informar sexo, idade e tempo de experiência como enfermeiro.

Todos os cuidados éticos referentes às pesquisas com seres humanos foram devidamente observados e este estudo foi aprovado por um Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa (Parecer 2.496.299). Logo, os pesquisadores comprometeram-se a manter em sigilo a identidade dos participantes e a não explicitar os serviços de saúde em que eles atuavam. Os dados coletados - isto é, os desenhos e as estórias dos participantes - foram analisados buscando-se a captação dos campos de sentido que sustentam o imaginário coletivo deles. Os campos de sentido, vale destacar, correspondem ao cerne do imaginário coletivo, visto que são constituídos por conteúdos não conscientes que, embora referentes à interioridade individual, possuem natureza intersubjetiva, porque se moldam continuamente a partir das interações sociais cotidianas(24).

Para viabilizar a captação dos campos de sentido, recorreu-se, acompanhando pesquisas psicanalíticas sobre o imaginário coletivo desenvolvidas anteriormente(13-16), à interpretação psicanalítica, operacionalizada em consonância com os procedimentos recomendados pela literatura(25). Assim, os pesquisadores examinaram as produções dos participantes, de modo exaustivo e com base na atenção flutuante, com o intuito de desvelar suas possíveis regras não conscientes estruturantes, ou seja, os pressupostos do funcionamento psíquico distinto daquele que determina a intenção consciente frente a pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia. Os resultados produzidos foram, então, discutidos e validados durante uma reunião do respectivo grupo de pesquisa. Tal expediente mostrou-se importante em pesquisas psicanalíticas prévias, pois possibilitou o refinamento de linhas de análise demarcadas pelos pesquisadores sem, contudo, incorrer em uniformizações reducionistas(13-16).

Resultados

O campo de sentido captado em resposta ao objetivo deste estudo foi denominado da seguinte forma: "Atendo, não nego, encaminho quando puder". Esse título, obviamente alusivo ao ditado popular "Devo, não nego, pago quando puder", justifica-se na medida em que, no imaginário coletivo da maioria dos participantes, ocupa lugar central a crença de que o acompanhamento de pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia é responsabilidade exclusiva de profissionais e/ou serviços de saúde "especializados". E tal crença aparentemente atravessa, de modo marcante, os (des)encontros que se estabelecem entre os enfermeiros e os referidos pacientes.

Assim, tem-se a impressão de que prevalece, entre os participantes, a lógica do encaminhamento, segundo a qual, na Atenção Primária, competiria, aos enfermeiros, apenas realizar um atendimento inicial e rápido de pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia para, na sequência, redirecioná-los, particularmente para os níveis de atenção em saúde subsequentes. A seguinte estória é representativa nesse sentido: [...] logo depois que passar pelo enfermeiro [o paciente com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia], é passado para a psicóloga. Se ela não se encontrar [...] o próprio enfermeiro, juntamente com a assistente social, conversam [sic] com ele para acalmá-lo e resolver a situação até no dia da consulta. (Participante 8)

Mas a lógica do encaminhamento se revela igualmente em uma estória extremamente concisa na qual nenhum acolhimento inicial na Atenção Primária é sequer mencionado: Paciente em crise foi encaminhado para P. S. para atendimento. (Participante 11)

É interessante sublinhar, na estória criada pelo participante 8, a utilização do verbo "resolver", o qual dá a entender que a situação retratada é vista como um problema que demanda uma resposta pontual. Em outra estória, o mesmo verbo também é veiculado, porém, à natureza problemática da situação é conferido maior destaque: [...] ao receber um paciente [com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia], tentamos acolher e resolver o problema [...]. (Participante 5)

Produções dessa natureza sinalizam que os participantes, tipicamente, tendem a atender pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia assim que eles chegam ao serviço de saúde e, referenciando-os, eximem-se de acompanhá-los ao longo do tempo. E outra estória sustenta esse argumento ao postular que o enfermeiro deve: [...] ouvir, apoiar e referenciar esse paciente [com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia]. (Participante 2)

Cumpre assinalar que um movimento análogo a tal tendência também foi observado durante a coleta de dados. Ocorre que todos os enfermeiros presentes na referida reunião foram convidados a participar do estudo. A maioria aceitou o convite, como já informado. Os pesquisadores então iniciaram a apresentação das instruções concernentes ao PDE-T, explicando que os participantes deveriam desenhar na folha de papel que estava sendo distribuída naquele momento e, para tanto, utilizariam um lápis que seria disponibilizado na sequência. Todavia, apenas quatro participantes aguardaram a entrega do lápis para iniciar a atividade. Os demais utilizaram canetas que já tinham em mãos, como se estivessem buscando "se livrar" rapidamente da atividade com a qual haviam consentido, ao passo que poderiam tê-la recusado inicialmente ou então dela desistir mesmo após a anuência prévia.

Parece razoável cogitar, assim, que algo equivalente pode se passar com certa frequência no cotidiano do trabalho dos participantes na Atenção Primária. Isto é, talvez, muitos deles, embora não se neguem a atender pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia, comumente o fazem procurando repassá-los o quanto antes para outros profissionais e/ou serviços de saúde. A estória do participante 8, citada anteriormente, também demonstra esse pendor, bem como a seguinte estória, em que uma enfermeira, de imediato, redireciona o paciente à psicóloga, que é quem encarrega de seu acolhimento: [...] enfermeira chama a psicóloga, que acolhe o paciente e agenda as consultas subsequentes. (Participante 9)

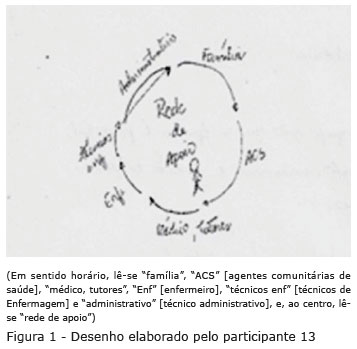

É possível propor ainda que, no tocante ao atendimento de pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia na Atenção Primária, os participantes, de modo geral, parecem empenhar-se em seguir à risca as diretrizes estabelecidas em manuais sobre a atenção em saúde mental e, consequentemente, acabam não personalizando o cuidado em saúde, o que pode incorrer em uma protocolização excessiva. Essa linha de raciocínio encontra respaldo nas Figuras 1 e 2, as quais remetem a fluxogramas presentes nesses manuais. Igualmente, a mera obediência às referidas diretrizes pode contribuir para a fragmentação da assistência, como evidencia a seguinte estória: [...] toda a equipe é envolvida no caso e delegado [sic] funções a cada um no intuito de minimizar crises e descompensações. (Participante 14)

Igualmente sugerindo o risco de uma protocolização excessiva, faz-se necessário sublinhar que as estórias de alguns participantes se assemelham a anotações de Enfermagem em prontuários, como sê no exemplo a seguir: Paciente chega na UBSF com esquizofrenia, é atendida pelo enfermeiro [...] Após avaliação, é feita uma abordagem multiprofissional com psicólogo e médico [...]. (Participante 7)

O mesmo se aplica a outra estória, em que foi colocada em relevo a qualidade do atendimento prestado pela equipe de saúde, porém, sem informar se o enfermeiro nela está inserido: Paciente comparece à unidade de saúde, com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia, é atendido pela equipe multiprofissional, com respeito e atenção, é encaminhado para avaliação em tutoria de Psiquiatria, realiza acompanhamento periódico. (Participante 4)

Discussão

Sabe-se que o acolhimento, para muitos profissionais de saúde, equivocadamente resume-se a uma ação de triagem administrativa seguida do repasse para profissionais e/ou serviços "especializados"(9). Os resultados aqui reportados indicam que tal concepção parece ser predominante entre os participantes deste estudo quanto ao trabalho desenvolvido por eles na Atenção Primária junto a pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia. Não obstante, o acolhimento necessita ser pensado como uma ação fundamental para o estabelecimento do vínculo com qualquer paciente, como já mencionado. Além disso, especificamente no tocante à atenção em saúde mental na Atenção Primária, o acolhimento deve fazer com que o paciente se sinta seguro no que diz respeito ao seu acompanhamento no serviço de saúde por ele acionado de início, ainda que seu atendimento venha a ser compartilhado com outro serviço(26).

Entretanto, para que consiga se responsabilizar efetivamente por qualquer paciente, todo profissional de saúde precisa contar com algo que geralmente não é disponibilizado a enfermeiros que atuam na Atenção Primária: espaços capazes de promover a continência do sofrimento psíquico vivenciado em função de seu trabalho. A premência de tais espaços foi salientada em um estudo psicanalítico acerca do imaginário coletivo de médicos especialistas em reprodução assistida sobre situações de difícil manejo(17). Os médicos pesquisados consideraram que o resultado negativo do teste de gravidez de uma paciente em tratamento provoca uma mobilização emocional acentuada, pois, de modo não consciente, demarca o limite de seus saberes técnico-científicos.

Os resultados obtidos neste estudo se assemelham àqueles oriundos de uma pesquisa qualitativa cujo intuito foi explorar a assistência ofertada por profissionais de Enfermagem inseridos em equipes de saúde da família a "pacientes de saúde mental"(11). As autoras constataram que o encaminhamento foi o recurso mais utilizado pelos participantes no atendimento do público em questão, pois a maioria deu a entender que buscava identificar rapidamente a queixa e avaliar a necessidade de redirecionamento a um profissional de saúde "especializado". Em síntese, foi evidenciada, como neste estudo, uma tendência à desresponsabilização dos participantes em relação às demandas de saúde mental.

Mas quais outros fatores contribuiriam para a predominância da lógica do encaminhamento entre os participantes deste estudo? Um estudo teórico sobre a atenção em saúde mental na Atenção Primária(27) forneceu elementos que auxiliam a esboçar uma resposta a tal questão. Ocorre que, para as autoras, mudanças nos processos de produção de saúde - em especial, aquelas preconizadas pela Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira - são extremamente complexas, pois exigem mudanças nos processos de subjetivação. Nomeadamente, ainda de acordo com o estudo teórico em questão, fazem-se necessárias a transformação do lugar social reservado à "loucura", a efetivação da desinstitucionalização do cuidado em saúde e a superação da dicotomia saúde versus saúde mental, já que as práticas clínicas não se alteram automaticamente com modificações nas políticas públicas de saúde.

Ao aprofundar-se no tema da desinstitucionalização, outro estudo teórico(28) defendeu que a atenção em saúde mental deve primar pela territorialidade, posto que somente assim o paciente pode ser conhecido em seu cotidiano e em suas necessidades, o que é indispensável para que sejam considerados os múltiplos determinantes do binômio saúde-doença na construção das intervenções a serem implementadas, preferencialmente, com o auxílio dos recursos de sua comunidade. Os autores ainda advertiram que, para tanto, não pode haver discriminação entre os "pacientes de saúde mental" e os demais pacientes. Mas, muitas vezes, não é isso o que se verifica, em particular no que concerne a pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia devido aos estereótipos e preconceitos que pesam sobre eles, fazendo com que o cuidado em saúde seja mais técnico e menos relacional, como sugerem os resultados obtidos neste estudo.

Cumpre assinalar que estereótipos e preconceitos igualmente podem prejudicar a atenção em saúde oferecida aos mais diversos públicos. Afinal, em um estudo psicanalítico sobre o imaginário coletivo de enfermeiras acerca da gravidez interrompida(18), constatou-se a predominância de uma crença segundo a qual a interrupção voluntária da gestação constituiria um ato hediondo, que somente poderia ser perpetrado por uma mulher insensível e cruel. Já uma pesquisa voltada à exploração psicanalítica do imaginário coletivo de agentes comunitárias de saúde sobre pacientes em sofrimento psíquico grave(19) revelou que eles geralmente são rotulados, de forma não consciente, como instáveis e perigosos por elas.

Os resultados ora reportados também dialogam, ainda que mais indiretamente, com aqueles obtidos em uma pesquisa qualitativa sobre a atenção em saúde mental ofertada por enfermeiros inseridos em equipes de saúde da família(12). Isso porque, na perspectiva dos enfermeiros pesquisados, o trabalho por eles desenvolvido junto às pessoas em sofrimento psíquico era pouco resolutivo devido tanto a dificuldades pessoais quanto à falta de qualificação profissional. Por outro lado, verificou-se que muitos - sobretudo, em virtude de estereótipos e preconceitos congruentes com os apresentados pelos participantes deste estudo - culpabilizavam apenas os pacientes pela não adesão aos tratamentos propostos.

Adicionalmente, faz-se necessário mencionar que há importantes pontos de convergência entre os achados deste estudo e aqueles oriundos de uma pesquisa qualitativa cujo objetivo foi analisar as práticas clínicas de enfermeiros e médicos quanto à atenção em saúde mental na Atenção Primária(10). Os autores notaram que o trabalho de tais profissionais visava, basicamente, ao cumprimento burocrático de protocolos, de forma que, muitas vezes, não era centrado no paciente, mas, sim, no transtorno mental com o qual ele foi diagnosticado e se limitava ao acionamento dos níveis de atenção em saúde subsequentes. Ressalte-se também que diversos participantes, ao definirem saúde mental, aludiram a estereótipos e preconceitos.

É válido sublinhar que a lógica do encaminhamento, em um sentido mais amplo, dificulta a efetivação da integralidade enquanto princípio do SUS, e não apenas no que concerne à atenção em saúde mental. O conceito de integralidade, conforme um estudo teórico(29), diz respeito a uma ação social, na medida em que exige uma interação democrática para a oferta de um cuidado em saúde capaz de produzir transformações na vida das pessoas por meio do acolhimento. E a autora salientou a importância do acolhimento tanto como momento de encontro, no qual o profissional de saúde busca dar resposta ao sofrimento do paciente que está diante dele sem reduzi-lo a um mero corpo a ser curado, quanto como modo de organização de práticas clínicas alinhado à necessidade de superação da fragmentação das atividades empreendidas em muitos serviços de saúde.

Por fim, é preciso admitir que o fato de muitos participantes deste estudo terem produzido estórias que se assemelham a anotações de Enfermagem em prontuários pode ser considerado, em certo aspecto, compreensível, levando-se em conta que tais produções são correlativas da linguagem mais familiar para eles. Isso determinaria uma limitação deste estudo. Não obstante, compreende-se que os resultados aqui reportados têm implicações para a prática clínica dos enfermeiros e para pesquisas futuras por, pelo menos, dois motivos. Em primeiro lugar, porque evidenciam que o alcance do trabalho desenvolvido por tais profissionais junto a pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia pode ser prejudicado - em especial, no que diz respeito à integralidade - por conteúdos não conscientes. Em segundo lugar, porque apontam que a circunscrição desses conteúdos é capaz de fomentar a superação de entraves ainda existentes quanto ao empreendimento de ações de saúde mental na Atenção Primária, particularmente aqueles que obstaculizam a territorialidade.

Vale enfatizar que o modelo comunitário preconizado pela Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira exige a corresponsabilização pelo cuidado em saúde, iniciativa por meio da qual se espera que profissionais de saúde inseridos em diferentes níveis de atenção construam conjuntamente estratégias direcionadas à qualificação das ações de saúde mental. Quando isso ocorre, tende a observar-se, além de benefícios para os pacientes, o aumento da capacidade resolutiva da Atenção Primária e, em contraste, a diminuição de encaminhamentos realizados automaticamente, o que otimiza o fluxo assistencial no âmbito do SUS(30). Contudo, parece razoável propor que a corresponsabilização depende do compromisso ético com um conceito de saúde mental ampliado a ponto de evitar fórmulas tautológicas, infelizmente ainda bastante comuns entre profissionais de saúde, que definem a existência de um transtorno mental como um impedimento a qualquer possibilidade de saúde mental(31).

Conclusão

Conclui-se que este estudo viabilizou a compreensão de aspectos do imaginário coletivo em relação a pacientes com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia por parte de um grupo de enfermeiros que atuam na Atenção Primária, com foco em suas possíveis reverberações no tocante à atenção em saúde mental e, assim, lançou luz sobre certas balizas simbólicas dos (des)encontros que se estabelecem entre os referidos grupos sociais. Em síntese, verificou-se que, em consonância com as crenças da maioria dos participantes, o público em questão é visto como responsabilidade exclusiva de profissionais e/ou serviços de saúde "especializados", o que é incompatível com os preceitos da Reforma Psiquiátrica Brasileira e com o papel a ser desempenhado na Atenção Primária pelos enfermeiros. Este estudo, portanto, reforça os achados de pesquisas prévias, bem como os aprofunda, pois se diferencia pela ênfase em conteúdos não conscientes que constituem o substrato ideativo-emocional de posicionamentos concernentes à atenção em saúde mental. Não obstante, devido à complexidade que caracteriza o assunto, novas pesquisas são necessárias, as quais, a propósito, podem se beneficiar do emprego de estratégias lúdicas na coleta de dados, como indicam os resultados ora reportados.

Propor supostas "soluções" para os entraves aqui apontados, no que diz respeito ao empreendimento de ações de saúde mental na Atenção Primária por parte de enfermeiros, excede o escopo deste estudo e soaria pretensioso. Logo, apenas sugerir um caminho passível de ser trilhado nessa direção mostra-se mais pertinente. Trata-se da oferta de espaços voltados à continência do sofrimento psíquico vivenciado por enfermeiros em decorrência das funções laborais no referido nível de atenção em saúde. Espaços com essa finalidade podem assumir diferentes enquadres, mas não devem ser confundidos com programas de capacitação, na medida em que devem ultrapassar o discurso técnico, partindo do princípio de que um olhar mais sensível às questões de saúde mental tende a emergir em profissionais de saúde que estabelecem maior proximidade com as próprias questões emocionais, ou que, em outras palavras, se dispõem a cortejar a própria insanidade*

Referências

1. Lei nº. 8080 de 19 de setembro de 1990 (BR). Dispõe sobre as condições para a promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde, a organização e o funcionamento dos serviços correspondentes e dá outras providências. [Internet]. Diário Oficial da União, 20 set. 1990 [Acesso 13 out 2020]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm [ Links ]

2. Zanetti ACG, Galera SAF, Souza J, Vedana KGG, Gherardi-Donato ECS, Luis MAV, et al. Mental health consultation-liaison from the perspective of the primary health care team. SMAD, Rev Eletr Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 10];15(3):1-8. Available from: http://www.revistas.usp.br/smad/article/view/163882/157374 [ Links ]

3. Gonçalves RC, Peres RS. Matriciamento em saúde mental: obstáculos, caminhos e resultados. Rev SPAGESP. [Internet]. 2018 [Acesso 10 set 2019];19(2):123-36. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/rspagesp/v19n2/v19n2a10.pdf [ Links ]

4. Starfield B. Atenção primária: equilíbrio entre necessidades de saúde, serviços e tecnologia. Brasília (DF): Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura/Ministério da Saúde; 2002. 726 p. [ Links ]

5. Yasui S, Luzio CA, Amarante P. From manicomial logic to territorial logic: impasses and challenges of psychosocial care. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(3):400-8. doi: http://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316628754 [ Links ]

6. Gondim GMM, Monke M. Territorialização em saúde. In: Pereira IB, Lima JCF, editores. Dicionário da educação profissional em saúde. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Editora Fiocruz; 2008. p. 392-9. [ Links ]

7. Backes DS, Backes MS, Erdmann AL, Büscher A. O papel profissional do enfermeiro no Sistema Único de Saúde: da saúde comunitária à estratégia de saúde da família. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2005;17(1):223-30. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012000100024 [ Links ]

8. Matumoto S, Fortuna CM, Kawata LS, Mishima SM, Pereira MJB. Nurses' clinical practice in primary care: a process under construction. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2011;19(1):123-30. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692011000100017 [ Links ]

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Núcleo Técnico da Política Nacional de Humanização. Acolhimento nas práticas de produção de saúde. 2ª ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2010. 44 p. [ Links ]

10. Nascimento AAM, Braga VAB. Atenção em saúde mental: a prática do enfermeiro e do médico do Programa Saúde da Família de Caucaia-CE. Cogitare Enferm. [Internet]. 2004 [Acesso 10 set 2019];9(1):84-93. Disponível em: https://revistas.ufpr.br/cogitare/article/view/1709/1417 [ Links ]

11. Sucigan DHI, Toledo VP, Garcia APRF. Acolhimento e saúde mental: desafio profissional na estratégia saúde da família. Rev Rene. [Internet]. 2012 [Acesso 10 set 2019];13(1):2-10. Disponível em: http://www.periodicos.ufc.br/rene/article/view/3756/2976 [ Links ]

12. Amarante AL, Lepre AS, Gomes JLD, Pereira AV, Dutra VFD. As estratégias dos enfermeiros para o cuidado em saúde mental no programa saúde da família. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2011;20(1):85-93. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072011000100010 [ Links ]

13. Simões CHD, Ferreira-Teixeira MC, Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. Imaginário coletivo de profissionais de saúde mental sobre o envelhecimento. Bol Psicol. [Internet]. 2014 [Acesso 10 set 2019];64(140):65-77. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/bolpsi/v64n140/v64n140a06.pdf [ Links ]

14. Pontes MLS, Barcelos TF, Tachibana M, Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. A gravidez precoce no imaginário coletivo de adolescentes. Psicol Teor Prát. [Internet]. 2010 [Acesso 13 set 2019];12(1):85-96. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/ptp/v12n1/v12n1a08.pdf [ Links ]

15. Manna RE, Leite JCA, Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. Imaginário coletivo de idosos participantes da Rede de Proteção e Defesa da Pessoa Idosa. Saúde Soc. 2018;27(4):987-96. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902018180888 [ Links ]

16. Russo RCT, Couto THAM, Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. O imaginário coletivo de estudantes de educação física sobre pessoas com deficiência. Psicol Soc. [Internet]. 2009 [Acesso 10 set 2019];21(2):250-5. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/psoc/v21n2/v21n2a12.pdf [ Links ]

17. Miranda KL, Serafini PC, Baracat EC. O cuidado psicológico em reprodução assistida: um enquadre diferenciado. Estud Psicol (Campinas). 2012;29(1):71-9. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2012000100008 [ Links ]

18. Tachibana M, Ambrosio FF, Beaune D, Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. O imaginário coletivo da equipe de enfermagem sobre a interrupção da gestação. Ágora (Rio J.). 2014;17(2):285-97. doi: http://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-14982014000200009 [ Links ]

19. Silva MABP, Peres RS. O imaginário coletivo de agentes comunitários de saúde em relação a usuários de saúde mental. Vínculo. [Internet]. 2016 [Acesso 10 set 2019];13(2):55-65. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/vinculo/v13n2/v13n2a07.pdf [ Links ]

20. Moreno-Küstner B, Martín C, Pastor L. Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195687. doi: http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195687 [ Links ]

21. Rosa DCJ, Lima DM, Peres RS, Santos MA. O conceito de imaginário coletivo em sua acepção psicanalítica: uma revisão integrativa. Psicol Clin. 2019;31(3):577-95. doi: http://doi.org/10.33208/PC1980-5438v0031n03A09 [ Links ]

22. Freud S. Dois verbetes de enciclopédia. In: Salomão J, editor. Edição standard brasileira das obras psicológicas completas de Sigmund Freud. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Imago; 1996. v. 18, p. 283-312. [ Links ]

23. Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ. Encontro com a loucura: transicionalidade e ensino de Psicopatologia. Tese [Livre-docência em Psicopatologia]. São Paulo (SP): Universidade de São Paulo; 1999. [ Links ]

24. Aiello-Vaisberg TMJ, Ambrosio FF. Rabiscando Desenhos-Estórias com Tema: pesquisa psicanalítica de imaginários coletivos. In: Trinca W, editor. Procedimento de Desenhos-Estórias: formas derivadas, desenvolvimentos e expansões. São Paulo (SP): Vetor; 2013. p. 277-302. [ Links ]

25. Herrmann F. Introdução à Teoria dos Campos. São Paulo (SP): Casa do Psicólogo; 2001. 210 p. [ Links ]

26. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Saúde mental. [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2013 [Acesso 13 et 2019]. 176 p. Disponível em: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/caderno_34.pdf [ Links ]

27. Vieira SS, Neves CAB. Cuidado em saúde no território na interface entre Saúde Mental e Estratégia de da Saúde Família. Fractal Rev Psicol. [Internet] 2017 [Acesso 10 set 2019];29(1):24-33. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/fractal/v29n1/1984-0292-fractal-29-01-00024.pdf [ Links ]

28. Lancetti A, Amarante P. Saúde mental e saúde coletiva. In: Campos GWS, Minayo MCS, Akerman, M, Drumond M Junior, Carvalho YM, editores. Tratado de saúde coletiva. 2ª ed. São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro (SP/RJ): Hucitec/Editora Fiocruz; 2012. p. 615-34. [ Links ]

29. Pinheiro R. Integralidade em saúde. In: Pereira IB, Lima JCF, editores. Dicionário da educação profissional em saúde. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Editora Fiocruz; 2008. p. 255-63. [ Links ]

30. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Coordenação Geral de Saúde Mental. Reforma Psiquiátrica e política de saúde mental no Brasil. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2005. 56 p. [ Links ]

31. Gaino LV, Souza J, Cirineu CT, Tulimosky TD. The mental health concept for health professionals: a cross-sectional and qualitative study. SMAD, Rev Eletr Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Dec 2];14(2):108-16. Available from: http://www.revistas.usp.br/smad/article/view/149449/151279 [ Links ]

Autor correspondente:

Autor correspondente:

Rodrigo Sanches Peres

E-mail: rodrigosanchesperes@yahoo.com.br

Recebido: 31.10.2020

Aceito: 14.12.2020

Contribuição dos autores

Concepção e planejamento do estudo: Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa, Rodrigo Sanches Peres.

Obtenção dos dados: Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa, Daiane Márcia de Lima.

Análise e interpretação dos dados: Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa, Daiane Márcia de Lima, Rodrigo Sanches Peres.

Obtenção de financiamento: Rodrigo Sanches Peres.

Redação do manuscrito: Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa, Daiane Márcia de Lima, Rodrigo Sanches Peres.

Revisão crítica do manuscrito: Débora Cristina Joaquina Rosa, Daiane Márcia de Lima, Rodrigo Sanches Peres.

Todos os autores aprovaram a versão final do texto.

Conflito de interesse: os autores declararam que não há conflito de interesse.

*Artigo extraído da dissertação de mestrado "Imaginário coletivo de enfermeiros em relação ao paciente com diagnóstico de esquizofrenia na Atenção Primária à Saúde", apresentada à Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brasil. Apoio financeiro do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brasil, processo nº 306676/2019-2, e da Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Brasil, processo nº PPM-00290-18.

**Alusão à canção "Sereníssima", da Legião Urbana.