Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Revista da Abordagem Gestáltica

Print version ISSN 1809-6867

Rev. abordagem gestalt. vol.24 no.2 Goiânia May/Aug. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18065/RAG.2018v24n2.9

ARTIGOS: ESTUDOS TEÓRICOS OU HISTÓRICOS

Case study in gestalt therapy: phenomenological readings of children's drawing

Mariana Vieira PajaroI; Celana Cardoso Andrade

IGraduada em Psicologia pela PontifÃcia Universidade Católica de Goiás, Pós-graduada em Gestalt-terapia, pelo Instituto de Treinamento e Pesquisa em Gestalt-terapia de Goiânia (ITGT), Mestre em Psicologia pelo Programa de Psicologia ClÃnica e Cultura da Universidade de BrasÃlia, Doutoranda em Psicologia Escolar e do Desenvolvimento Humano pela Universidade de São Paulo. Coordenadora e Professora do Instituto Figura-Fundo (IFF). Email: marianapajaro@uol.com.br

IIGraduação em Psicologia pela Universidade Católica de Goiás, Licenciatura em Educação FÃsica pela Escola Superior de Educação FÃsica de Goiás, Especialização em Gestalt-terapia pelo Instituto de Treinamento e Pesquisa Em Gestalt Terapia de Goiânia - ITGT, Mestrado em Psicologia ClÃnica pela Universidade Católica de Goiás, Doutora em Psicologia ClÃnica e Cultura pela Universidade de BrasÃlia, Professora Assistente e supervisora de estágio no Curso de Psicologia da Universidade Federal de Goiás. Email: celana@terra.com.br

ABSTRACT

The present study approaches children's drawing as a revealing feature of the child. It aims to illustrate the psychotherapeutic process of a boy of 6 years from the phenomenological reading of seven drawings made by him during his visits. In addition, it intends to reflect on the contributions of this case to the understanding and intervention in the children's clinic from the Gestalt therapy perspective. To do so, he carried out a documentary case study ex post facto descriptive from the field diary of the psychotherapist, which contained the drawings of the participant and their respective notes. The phenomenological methodology favored the access to the lived one through descriptions of the client that could extend the contact with its experience. The author of graphic production is therefore conceived as the sole holder of the meaning of his work. This study shows that the design may favor the expression of some children in order to contribute to the psychotherapeutic process in Gestalt therapy.

Keywords: infant design, Gestalt therapy, phenomenological method; case study.

Introduction

Children's drawing is a powerful resource revealing the ways of being and being in the world of the child. Studies on the subject show, predominantly, different readings and theoretical approaches that support a diversity of possible understandings to this type of production (Aguiar, 2004, Derdyk, 2015, Ferreira, 1998 and Mèredieu, 2006). Despite this variety, it is possible to observe the absence of studies aimed at illustrating, based on clinical cases, its contribution to the psychotherapeutic process - especially from a Gestalt therapy perspective. In this approach, the reading of the drawing is made by the phenomenological methodology, when it excels by the incessant search of the apprehensibility of the object, finally, by the conscience. This means not to stick to the subject itself, the child, falling on a subjectivism, nor to stick solely to the drawing, configuring an objectivism, but to the intersubjective way this drawing is captured by this consciousness, that is, in the relation of this child with its work.

This study is justified by the lack of studies with such a cut that allow a theoretical-practical discussion of the work of the psychotherapist of the Gestalt approach regarding the possibility of using the drawing by the client in the psychotherapeutic process. In addition, it presents an alternative understanding model, in opposition to the traditional apprehensions of this resource, anchored, above all in the phenomenological methodology and other concepts of this approach, such as awareness, contact and contact functions. From now on, it offers to parents, educators and other professionals the possibility to broaden their looks for the relevance of drawing, an expression so recurrent in childhood.

The guiding question of the study is: in what way can children's drawing contribute to the child psychotherapeutic process of the Gestalt approach? To answer this question, the main purpose of this paper is to illustrate and describe the psycho-therapeutic process of a child based on the phenomenological reading of seven drawings performed in the sessions. Secondarily, it will reflect on the general contributions of the illustrated case to the understanding and clinical intervention in drawings from the Gestalt therapy perspective with children. Data presented here were collected from the records of the responsible psychologist and will be composed of the copy of these drawings and the remarks referring to each session of the participating child.

To support this study, we will present below the fundamental principles of clinical care with children in Gestalt-therapy and the reading of children's drawing from the phenomenological method. It is important to note that, although grief is the predominant theme in the case studied, we decided not to explore its theoretical basis since it does not contemplate the objectives proposed in the study -centered on the methodology of working with drawings in a psychotherapy process, and not on the specificity of their content which, therefore, imposes a necessary clipping.

Child Psychotherapeutic Process in Gestalt-therapy

Child psychotherapy is distinguished from the assistance of other publics due to two fundamental aspects: the scope of care and the way of accessing the world of the child. In terms of scope or breadth, and in agreement with the field perspective developed by Kurt Lewin, in the clinic with children, Gestalt therapy is concerned with exploring the range of contexts of which it forms part, and to which it constitutes the in order to know the diversity of perceptions about it, the multiple influences to which it is subjected to and produces (be they familial, social, cultural, etc.), as well as the complementarity present in existing relationships. This means that, according to Gestalt therapy, the child's understanding comes from the micro- and macro-systems to which it belongs and with which it interacts - which is justified both by the dependency situation to which it is subject and by the interweaving of realities that are co-constituted. That being the case, any symptom, behavior, emotion and sensation of the child can only be understood in terms of its field.

In general, the first and main context of the child is the family, however, we must consider the contemporary movement of schooling that is increasingly precocious (and more extended) that has given the school a position of increasing importance in children's daily life. These contexts are understood as the "background" that gives meaning to the child's manifestations, besides exerting great power and influence on the psychotherapeutic process (Aguiar, 2014). As a result, sessions are held with those responsible and significant persons, visits to the school and communication with other professionals, in case the client does some other type of follow-up (Aguiar, 2014; An-tony, 2010; Fernandes, 2016; Zanella, 2010). The literature is divergent in the way of defining the frequency of such meetings (Aguiar, 2014; Antony, 2010; Fernandes, 2016; Oaklander, 1980; Zanella, 2010), however, advocates a flexible regularity, that is, periodic meetings which, above all, meet the need in each case.

In childcare, parents (or guardians) are also clients of the psychotherapeutic process of their children (Fernandes, 2016). This statement is consistent with the view that the psychotherapist should also welcome them in a careful and attentive manner, since they are the greatest influence in the child's life, those responsible for the decisions to be made and the core of its coexistence. The idea of giving parents an active role in caring for their children does not violate the limits of work that always use the child as a starting (and returning) point for understanding its environment. The family develops a mode of functioning among its members, thus, working with any of its members affects the entire relational field. The feasibility and availability of this integrated whole to reconfigure itself in the face of the new developments arising from psychotherapy will also depend on the support offered by the psychologist and the link between them. Many services are early interrupted or do not evolve due to too much focus on the child and consequent negligence of those responsible: neglecting the family is neglecting the child.

In spite of the second particularity of this care, and taking an analogy, attending children requires that the psychotherapist resume the exercise and understanding of a language already "spoken" previously - as a child - and often forgotten when distancing him/herself from his/her childhood during the process of becoming an adult. After all, "few lucky ones insist on continuing children" (Ribeiro, 2015, p.35). The play is the language of the child (Aguiar, 2014; Zanella, 2004), so it predominates in this service and stands out as the main differential in relation to the way of access to the other age groups. Thus, when playing, psychotherapist and child are in a common territory and share the same dialect. Recovering this expression involves the rescue process of the psychotherapist's own child (Aguiar, 2014; Zanella, 2004; Oaklander, 1980) as he/she delves in his/her childhood memories: "it is not so much a matter of remembering incidents and events, but remembering to be" (Oaklander, 1980, p.350).

Through "play with", the gestalt-therapist is interested in the child and its functioning, in its life and history, its configuration, perception and acting in the world. Although it may sound superfluous or confusing to some, reiterating that the child psychotherapeutic process occurring through play does not exclude its relevance and seriousness. On the contrary, the relevance of play is emphasized by Huizinga (2014) because it is a phenomenon that goes beyond the limits of purely physical or biological activity because it contains an expressive, meaning-filled function. For this author, the expression homo ludens expresses the conviction that it is in play and by playing, innate activity to man, that civilization develops, and the play aspect is one of its main bases. In addition to a possible mode of communication with the child, playing implies a physical, biological and emotionally vital function for the man 'capable of absorbing the player intensely and completely" (Huizinga, 2014, p.16). Hence the recurring perception that playing on its own is therapeutic - even if it is not necessarily psychotherapeutic.

Playful resources and toys are important because they favor playfulness, expression and creativity of the child - although they are not indispensable to emerge games in the clinical context or outside. Some examples are: drawing, games, family of dolls, puppets, house, animals, modeling dough, clay, story books, sandbox, among others. In the context of psychotherapy, they are relevant because they act as an invitation and encouragement to the child, in addition to concretizing the approach of that adult with the child world. The use of such resources in the Gestalt perspective should be in line with the phenomenological methodology, which invites the psychotherapist to exercise of apprehending the child based on this perspective, to the detriment of possible misconceptions resulting from personal interpretations of the professional (Aguiar, 2014).

Phenomenological reading of children's drawing

Phenomenology (translated from the Greek "study of the phenomenon") is a philosophical school, whose father and master is Edmund Husserl, and began in Germany in the late nineteenth century (Bello, 2006). Pray for the phenomenon as that which appears "before me", not "in me" (Holanda, 2014), and contemplates consciousness as intentional. Unlike the sense of intention as a volitional act, the intentionality of consciousness refers to the dialectical relation that conceives consciousness as the capture of the world, directing towards the object, essential correlation without which there would be neither consciousness nor object, since this is what gives it meaning (Andrade, 2007).

Unraveling the Phenomenology, Holanda (2014) describes it as an epistemology, a philosophy, a science and method. According to the author, in epistemological terms, it is concerned with the possibility of knowledge and knowing, as a critique of science itself in its original sense; as philosophy, it is understood as the reflection on reality; as science, comprises a systematized knowledge about something; and as a method, encompasses a research methodology of this same reality. In this regard, Ribeiro (2012) clarifies that the approximation of psychology with Phenomenology is by analogy and extension, when seeking in this a method of understanding reality that helps the gestalt-therapist to read and describe what is present before him/her, that is, the phenomenon.

In Gestalt therapy, children's drawing is a concrete form of expression. The interest of the gestalt-therapist is to access, through the investigation, description and understanding of the phenomenon, the experience lived and expressed by each child, in each of its productions. In this perspective, children's drawing is recognized as an authorial production, full of meaning, that only the child itself has the translation - and not the other, whoever he/she may be. In this direction, phenomenology contributes through the search for an instrument of investigation of the psychological that is more human and less laboratorial (Aguiar, 2004). To draw is primarily an attempt to approach the world (Derdyk, 2015) and, concretely, an act in it.

In school years, a "right" way of drawing and painting is learned in schools, usually within the line and with colors "coherent" with reality, repeating for centuries the standardization of teaching that annihilates differences and blocks creativity. The green cloud and the scribble, for example, tend to be reprimanded for escaping from customary norms, which have direct implications on the child's unique and creative expression since they denounce a kind of exploitation or subversion (Derdyk, 2015). The rectangular field of paper, adds the author, gives the drawing its potentiality as an instrument of reflection, abstraction and conceptualization insofar as it becomes the field of possibility, reverie, invention, the concretization of its needs and desires - phenomena for which psychotherapy is interested.

Some children feel embarrassed, and claim to have no skill with drawings, opinions often derived from external judgments that can generate resistance to this experience. Therefore, the use of this resource is not always given spontaneously, and it may occur through an invitation from the psychotherapist. Faced with this resistance, it is opportune to differentiate some alternatives of the psychotherapist's conducts in relation to the client: to praise, to manipulate and to encourage the child. Praise may come with professional statements that try to convince that the child is capable, which invalidates its feeling (that is not good), and therefore breaks with the psychotherapeutic principle of confirmation. Manipulating, in a clear or veiled way, happens when the child is directed, independently of its will, to do what the psychotherapist proposed using a bargain, in order to meet a personal need and not of its client. Unlike the previous ones, to encourage the child is an act that welcomes its perception while inviting it to try to go beyond, propitiating contact with the new one through a supportive relation. Thus, the psychotherapist clarifies in his/her call that there is no right or only way to draw, that this is not what matters in that context, but the freedom to do it as you want and achieve. With this encouragement, some children are encouraged, others keep the same decision: whatever the choice, you have to respect and move on.

The phenomenological reading makes possible the understanding of the drawing through its description, which can only be done by the author itself. Aguiar (2014) corroborates that this form of work allows the child to gradually construct the meaning of its material. The psychotherapist will be able to help with interventions that can broaden its perception, taking care that the questions do not come to an interrogation that will not make sense. This is contrary to the behavior of the professional who blindly imposes his/her own childhood image when interpreting children's drawings (Derdyk, 2015). It is intended, in the clinical care in Gestalt-therapy, using the phenomenological method, the exercise and the constant search for the subject of the experience, for its experience lived as it perceives it.

Method

This is a case study from a documentary, descriptive ex post facto research, with the description of free drawings of a child with a finished psychotherapy process. The ex post facto research is characterized by the data being used after the occurrence of the event, in this case after the end of the client's psychotherapy. The documentary character refers to the use of such drawings as a source of scattered information that can be reorganized, giving them a new importance as a source of consultation (Prodanov & Freitas, 2013). The authors complement:

We understand by document any record that can be used as a source of information, through investigation, which includes: observation (critical in the data of the work); reading (criticism of the guarantee, interpretation, internal value of the work); reflection (criticism of the process and content of the work); criticism (reasoned judgment on the value of the material usable for scientific work. (p. 56)

The choice for the case study comes from the need to understand the human phenomenon in a holistic perspective, in which there is no control of the researcher about the events involved. The case study is useful to investigate new concepts as well as to verify how elements of a theory are applied and used in practice (Yin, 2009). To do so, we will use seven drawings, made in different sessions, and the psychotherapist's record book containing the records of attendance, that is, the textual reports of the professional on the work performed at each visit of the child.

Participant

Peter (fictitious name) began the process of psychotherapy at the age of six, shortly after the murder of his father in the exercise of his work as a police officer - a complaint referred to by the person in guardian. In the new family configuration, he lived with her mother and his 10-year-old brother. With considerable repercussion of the case in the press, the sudden death of the father was the predominant theme of his attendance, highlighting games that often involved losing/winning antagonism. His maternal family, with which he had more coexistence, is of Japanese origin and was characterized by a restrained expression. The mother, in particular, clearly reported her difficulty in showing her children her suffering, and consequently habitually chose not to talk about it. Psychotherapy lasted for one year and ten months, totaling 49 sessions.

Results and Discussion

Next, we will present some drawings of Pedro, followed by description, and reflections on the phenomenological method as contribution of the illustrated psychotherapeutic process. The starting point of a graphic production is the description, that is to say, the child is asked to tell how it "lives" that experience, feelings and, by extension, its drawing - Aguiar (2004). The author affirms that only in this way will it be possible, in the presence of the psychotherapist (and with him/her), to achieve the co-constituted single meanings and senses, an inexorably possibility articulated to the word. The phenomenological premise outlined here rests on the prospect of going to the same things, apprehending the world as it is, by means of a "naive" look and before any reflection (Holanda, 2014). In view of the risk of misappropriating Phenomenology as a philosophy, the idea of possible transposition to Psychology concerns the phenomenological method in terms of methodology, not of technique. In other words, as described by Holanda (2014), it concerns the use of Phenomenology as a method to understand the psychic phenomenon.

Pedro comes to psychotherapy brought by his mother a few days after the loss of the father that occurred in an unexpected and tragic way when being shot to death at work as a police officer. At the time, she explains the emergence of psychological counseling for her son who, even present, remains silent and head down in the face of his mother's emotional reports. At the end of this first contact, the child was consulted about his interest in returning to the psychotherapist office and agreed. In his first individual sessions, Pedro did not speak spontaneously on the subject of his father's death, nor was he receptive to the approaches of the psychotherapist. Gestalt-therapy, in its clinical posture, is guided by respect for the client's choice, giving him the decision on what to address or do in the session - which also applies to the child's context.

The child who comes to psychological assistance, brings with it a sacred ground and completely unknown to the professional who receives it, source of curiosity and, fundamentally, of respect. In view of this, the psychotherapeutic bond can be compromised as soon as the psychologist expects the child to address the same complaint referred to by those guardians, which may interfere with and hamper its authentic manifestation. On the contrary, for the most part (and for different reasons), they come with other interests and themes for the session. Such discrepancy may relate, for example, to a difference in need and/or perception among members of the same family; in other cases, it may indicate a difficulty in approaching the demand that is sometimes a source of excessive suffering for the client. In this case, getting away from the subject may translate what Hycner (1995) calls "wisdom of resistance", that is, when a person feels for some reason that do not have sufficient support to deal with a particular situation and therefore stay away from it as an organismic attempt to protect itself. Perls (1977) corroborates this understanding by proposing the idea that not all coping is healthy, not all escape is unhealthy if considered the best possible way to be at a given moment.

The first plays of Pedro remained uninteresting and, notoriously, did not include the psychotherapist. It is fundamental that the professional knows how to tolerate the time, silence and anxiety of the child of "not knowing what to do" in this new context (Aguiar, 2011), or even its non-availability to the relationship at any given time. Gestalt-therapy understands that there is no correct or expected mode in relation to the child's behavior in psychotherapy, which refers to the distressing and necessary exercise of the psychologist: to accept the authenticity of the child in its infinity of manifestations. It requires, therefore, a human opening from which facilitates the emergence of the client's being (Holanda, 2014), although this posture involves relative discomfort in the psychotherapist. In this phase of the visits, the professional reports in the records of the case her distress for not addressing the issue of the death of Pedro's father, given the impact of this theme on her and her willingness to help him.

In situations where there is a real difficulty in attending, the assistance of a more experienced professional to guide and supervise the case becomes fundamental for the progress of the process. Faced with the sensations referred to by the psychotherapist, the supervisor warned her that talking openly about her father's death seemed not to be the current need of Pedro. Accompanying the spontaneous emergence of the child required the professional to work with her own anxiety and expectations resulting from the encounter with this client. Unlike what she expected, at that moment, Pedro "only" wanted to play. Although it seems simple and unpretentious, it is "by playing that the child comes into contact with its pain, its fears, its anger, its emotion, its affection, its love; is a laboratory of its life" (Zanella, 2004).

In his ninth session, Pedro, in constructing a scenario with building blocks and human figures, he identifies the father and finds it inside his house, telling the psychotherapist how much he perceives him in that place. From this time on, it was possible to identify the beginning of a cyclical movement of gradual approximation and withdrawal of this theme that had been repeated throughout its psychotherapeutic process: if in a session the child approached his present experience in relation to the loss of the father, especially through drawings, at the next meeting, he chose any other activity that did not make a direct reference to grief - and so on.

In the psychotherapeutic process of Pedro, drawing proved to be a possible mode of access to the experience of the father's death. Drawing is understood as the result of an activity that emerges from the imaginary, from the perceived and the real, which becomes the object of investigation and exploration (Ferreira, 1998), therefore, a starting point for descriptions and perceptions arising from them. Given its breadth, it is not merely a technique, which would imply a reductionist view, but a revealing activity of human experience (in any age group) that can be used in the psychotherapeutic context from a theoretical-methodological framework consistent with the practice established. The Phenomenology, the basic philosophy in Gestalt-therapy's foundation, understands that, contrary to the traditional explanatory perspective, characterized by an aprioristic attitude in which one considers the understanding of the phenomena from something given and put before, to do Phenomenology is the exercise of continuous and uninterrupted questioning of appearances (Holanda, 2014), in the endless search for the understanding of the subject of experience.

The descriptive mode of investigation, different from the deductive one, postulates that the phenomenon shows up by itself and will be known by such a way, without assuming that there is something behind what is shown (Feijoo, 2010). In this logic, the phenomenological methodology removes the psychotherapist from the place of the supposed-knowledge subject, holder of the truth about the client. In relation to drawing, this means recognizing the child's place as an idealizer and, consequently, a better interpreter of its creation, repositioning it in an active role in its production (Aguiar, 2004).

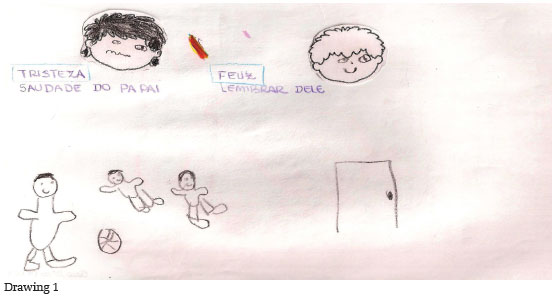

From the tenth session, the first drawings of Pedro begin to appear. Realizing his difficulty in expressing himself through speech (a common characteristic among children, especially in the context of tragedies), the psychotherapist proposed that her client freely use a sheet of paper to express what he was feeling at that moment. In drawing 1, Pedro speaks of the feelings of missing and sadness for the lack of the father. In parallel, he says he feels happy when he remembers they playing soccer, when his father handed him the ball so he could score the goal - he describes. Talking about the drawing, starting from his description, new feelings were manifested, as when he tells of his fear of losing others he loves.

When polarities appear in the same drawing, as in the example of sadness and happiness, it is essential that both be welcomed in their legitimacy, as the total experience lived and perceived. Thus, the psychotherapist does not privilege one or the other feeling, instead he/she can make readings that explain this totality or suggest experiments that "put them to talk", such as asking what one feeling has to say to the other. In addition, he/she can ask the child to choose one of them to try to dialogue, color, locate in the body where it concentrates, express with a body movement, etc. The child is then invited to do the same with the polar feeling. All these options, and many others that allow creativity to emerge in the psychotherapeutic context, are playful ways of exploring the functions of contact (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, speech and movement), thus being relative to the way the child captures and perceives the world of which it is part and is in relation. Although one of these modes can be contemplated at a given moment, such contact experiences involve, fundamentally, being touched, that is, contact as a form of touch (Polster & Polster, 2001). In the Gestalt-therapy perspective, contact has to do with "relating to, encountering with oneself and with others, without ever losing sight of everything happening in the world" (Ribeiro, 2006, p. 91).

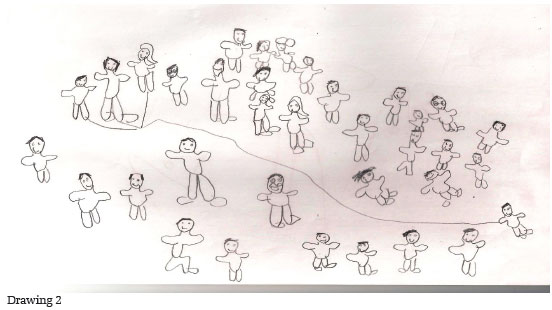

In the following sessions, the psychotherapist and the client talked and played with different feelings, so that Pedro became familiar with human emotions - as he initially showed some of them to be unaware of and have difficulty naming them. He could, by means of another drawing, try to locate them in the body and give color to each one of them: he painted the miss of his dad with black and located it in the heart. In this direction, Derdyk (2015) describes that through investigation and experimentation new meanings arise between the child and the adult. In drawing 2, when invited to draw his family, Pedro chooses to represent respectively his mother, brother, uncles, grandparents and cousins - as he narrates in pointing and naming each one of them.

After describing who the people were, one by one, the psychotherapist realized that the father had not been represented in the drawing, nor mentioned among the relatives named: it was the first time that he was not concretely present. The novelty experienced in the paper and captured by the professional was reported to the child due to the update outlined graphically. The psychotherapeutic intervention is marked by the possibility of favoring the opportunity of new understandings and experiments, which foments the confrontation of the new (Fernandes, 2016, Aguiar, 2014). When Pedro realizes that he had not illustrated it, he immediately draws him in the corner of the page, linking it with a line to him, to his mother and brother. To facilitate the child's contact with itself, it is essential to work with its senses in order to expand and integrate its perceptions. At this moment, the child is invited by the psychotherapist to touch the line drawn and pay attention to what he feels as he does so. After passing his hand over the line a few times, he describes that the line that connects them is nostalgia. This proposal evidences the invitation to recover the willingness to see and touch and feel the effects of this look (Polster & Polster, 2001).

In the following drawing, after some sessions, Pedro describes his father in the sky, above the clouds, and his family underneath. The dotted line, according to him, is his father's way back: he tells of having watched in a movie that after people die, they come back. Drawing reveals a person's introjections and beliefs that are often not directly accessed by his speech. The psychotherapist is only a facilitator in this process of investigation and understanding (Soares, 2009).

Developing the child's expression and listening to it with acceptance is a task of the gestalt-therapist that must be shared with the family. This means that the more she experiences and risks showing herself in a secure relationship and context, the more likely it is that she will surpass the therapeutic setting. In the care of Pedro, some sessions were aimed at the mother's guidance, with the aim of favoring a welcoming posture with respect to her son's pain. In this sense, the sessions with the guardians are intended to listen to them and talk about issues related to the child that are pertinent to the progress of the process (Aguiar, 2005). Such meetings hold within the rich possibility of the psychotherapist to know the functioning of the family and its belief system, essential aspects in the behavioral breakdowns presented by the child.

In the course of the visits, and in the continuous follow-up with the family, new demands emerge in psychotherapy. This means that old behaviors give room to new ones, not always accepted and welcomed by context, given the arrangement of these new configurations articulated by the child. At this stage of the process, the mother informs the psychologist of her discomfort in the face of the child's new manifestations of discontent, described by her as "tantrum". Creative adjustment refers to how a person can organize around his or her experience, and may be considered dysfunctional when it becomes a generalization in the face of different contexts (Aguiar, 2014, Antony, 2010, Fernandes, 2016). In one of his subsequent attendances, Peter begins to realize that his shouts and tantrums are the way he found to be heard and seen by people - which can be easily understood if considered his family context governed by silence. From then on, evidencing its necessity, it became possible to approach new ways - more effective for him-to show and be seen by those who wish, as well as to increase the understanding of the functioning of the family field. Pedro finishes this service saying that what he learned in this session is that "every day we feel". By prioritizing a greater in the world (Aguiar, 2014). This means making clients aware of what they are doing, how they are doing and how they can transform themselves (Yontef, 1998), favoring an integrative self-perception at the affective, cognitive and motor-sensory levels, whereby a person can "realize" itself in the world.

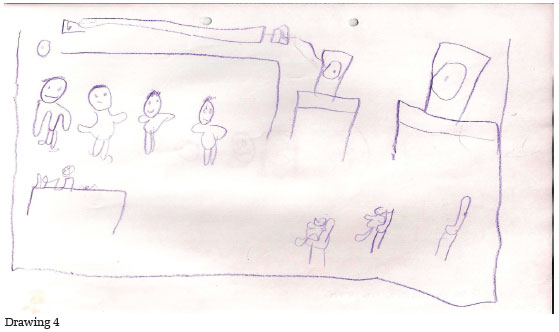

Near the father's day, the school and the family requested support of the psychotherapy, for not knowing how to handle the commemorations of the date. The view of the school is fundamental as it complements the client's history and provides relevant information to a better understanding of its reality, which requires an efficient exchange between these two contexts (Aguiar, 2014; Zanella, 2010). In this session, when informed about this concern, Pedro is invited to draw what he imagines of the father's day party that will happen in the school. In drawing 4, describing his fantasy, he narrates the scene with children singing, a table of souvenirs, another with the sound, and the space of the parents: his father's chair is empty.

Making contact with his sadness, Pedro asks that his grandfather to not participate in the celebration representing his father (proposal of the mother) and, finally, decides not to attend the party. When communicated by the child about his will, the mother can support him with a welcoming and understanding attitude, which reveals significant steps of her personal process carefully covered throughout the care. This illustrates the breadth of child psychotherapeutic work that extends to the family as a possibility to support the child's new experiences. It is important that psychotherapy helps to identify needs and the search for their satisfaction. By self-managing, the child begins to respect itself, strengthening its self, which will give it support to face events perceived as negative (Antony, 2010). According to the author, self-nutrition makes the child able to take care of itself, by being able to integrate denied parts to the total experience.

With the passage of time, visits began to have new configurations, in which grief no longer appeared as a figure. New games and plays arose and, at the same time, some faults. Pedro seemed not to be interested in new subjects, showing a decreasing energy in the attendances and gradual disinterest for the sessions. The psychotherapist, in her supervision, is alerted to possible signs of the end of the process of Pedro. At the 40th session, all drawings made and stored with the client's permission are placed on the floor by the psychotherapist, in the order in which they were performed. The mosaic formed by his productions graphically illustrated the process of lived psychotherapy. Looking at it, Pedro enters in deep silence, moved. This model of intervention can be applied in situations in which it is necessary to highlight the trajectory of the child psychotherapeutic process in a concrete way, and may include the different productions of the client; allowing a clear view of its walk.

The child in psychological counseling signals in different ways when the natural end of its process approaches, we must be alert to signs that indicate the term. The family that searches for child psychotherapy brings with it a complaint that, when welcomed and worked among its members, usually gives rise to new demands that demand attention. Nevertheless, confusions can affect professionals who have mistaken expectations about the duration of such follow-up, such as when they relate efficiency to time or even when they discredit the self-support of the child and the family to walk without their help. The fact is that each system has its necessity and its rhythm which, when contemplated, naturally leads to the end. Some signs of termination are related to fluidity and flexibility in the way the child is placed, in the new solutions it encounters for everyday issues, remission of the initial symptoms, reduced enthusiasm with the session, faults, interest in other activities at the same time of the meetings (Aguiar, 2014; Antony, 2010; Fernandes, 2016). Once the possibility of conclusion is identified, it is essential to pay particular attention to works on terms and separations (Agu-iar, 2014).

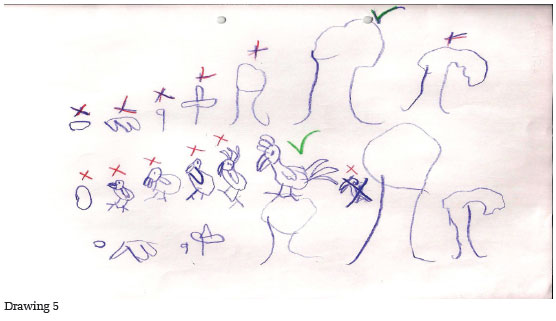

The playful alternative of closing this assistance was based on the analogy with the natural development of life: to be born, to grow and to die in correlation with the process of initiating, developing and finalizing sessions. Drawing on this metaphor, Pedro drew the development of different living beings. Then, at the request of the psychotherapist, he was able to identify the moments he spent in psychotherapy and to locate himself in the here-now. In drawing 5, he represented with an "X" the steps he perceived as completed, and with "√" his current moment in the process: "I am entering the end". In the children's world, drawing promotes the realization of the experience, so necessary to the understanding of younger children, facilitating their perception. "Art does not imitate the visible, it makes visible" (Klee, 1977, apud Derdyk, 2015).

Talking about separation, loss, farewell, are indispensable care behaviors to a closure (Antony, 2010). As an end is evident, which refers to the impossibility of Pedro to say goodbye to his father-the central theme of his process - the psychologist assures him in this context the possibility of being able to "say goodbye" to her and her care. At that moment he asks: "I want 22 sessions to say goodbye" -request accepted by the psychotherapist. Not by chance, after six sessions, Pedro closes the appointments, by choice. He finishes with 2 drawings: one on the father (drawing 6), and the other on the most important moment for him in the meetings (drawing 7). In drawing 6, he describes his father in heaven, beside God looking at his family, who still lives a storm. In drawing 7, he depicts the day we made the visit a movie session, with the presence of his brother, at which time, although the theme of the father's loss had not been explicitly worked, they watched the film "Up", suggested by the psychotherapist, which makes mention of death.

Pedro, therefore, reproduces as a milestone in his process a situation in which, instead of explicitly approaching pain, they lived a playful moment. The suggestion of the movie, the fruit of intersubjective perception, reaffirms the relevance of the dialogical dimension in Gestalt-therapy. In such a way, "the therapist should not only be friendly, but must be willing to effectively contribute with his/her own self to the encounter" (Hycner, 1995, p. 113), whatever the possible formats for it to happen. This reiterates the premise that there is no more or less effective technique, a stiff format common to children cases: the creativity of the psychotherapist and the child, combined, must be in the service of the present need, which involves, in all probability, the capacity to perceive the other. The evidence of the encounter with the human transcends (or should!) theories and technicalities.

Final Considerations

Children's drawing is a "trigger" feature through which the child's experience is revealed. Although not all children have proximity and opt for this resource, when adopted, it can facilitate the expression and promote awareness, corroborating to the purpose of this approach. The phenomenological readings express the impossibility of deduction or interpretation by the psychotherapist of the material produced, since they are subject to the rigor of this descriptive methodology of the subject.

Although the drawing is a resource loaded with meanings, it is extremely careful not to "immobilize" the child in its production. According to the principles of Gestalt therapy, it represents a form of being-in-the-world in its here-now, not a rigid and unchanging representation of its reality - a contextual dimension. Oaklander (1980) looks at the responsibility of the child psychotherapist to provide methods for children to express their feelings, since often children coming to psychotherapy do not know how to do it. This confirms the relevance of this professional being committed to the constant questioning of the drawing, since its openness is fundamental to work with this type of language - when this is the client's choice.

Psychotherapy has the role of accompanying the child in its construction of meanings and perception of the world and in the world. Thus, it is expected that the child psychologist works, not in an ideal of "cure", but focused on contributing to the free flow of the child in its larger context. This means recognizing in the graphic elaboration the subject of production and all its intrinsic temporality in this manifestation. The phenomenological exercise is to read behind the rationalities, in the constant search for the singularities and connections of the child with the world.

This study was able to explain the psychotherapeutic process of a child, highlighting some of the endless possibilities of intervention. It is not intended here to exhaust them, but to reaffirm the invitation to reflection that involves foundation and practice. The limits of the study are concerned with displaying a case in which drawing was fundamental to the process, which obviously is not unanimity. It was concluded that drawing was a favorable expression path in this case study by the affinity of the child and the psychotherapist with this form of work. Therefore, we suggest studies that can reveal the scope and limits of other resources based on existing (or not) compatibility with psychotherapists and their clients.

References

Aguiar, E. (2004). Desenho livre infantil: leituras fenomenológicas. Rio de Janeiro: E-papers. [ Links ]

Aguiar, L. (2011). O brincar na psicoterapia e a ansiedade do psicoterapeuta em "saber" e "entender". Recuperado em Julho de 2013, de http://www.gestaltcomcriancas.blogspot.com.br [ Links ]

Aguiar, L. (2014). Gestalt-terapia com crianças: teoria e prática. São Paulo: Livro Pleno. [ Links ]

Andrade, C. C. (2007). A vivência do cliente no processo psicoterapêutico: um estudo fenomenológico na Gestalt-terapia. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Católica de Goiás, Goiânia. [ Links ]

Antony, S. (2010). Um caminho terapêutico na clínica gestáltica com crianças. Em S. Antony (Org.), A clínica gestáltica com crianças: caminhos de crescimento. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Bello, A. A. (2006). Introdução à Fenomenologia. Bauru: Edusc. [ Links ]

Cardoso, C. L. (2013). A face existencial da Gestalt-terapia. Em Gestalt-terapia: fundamentos epistemológicos e influências filosóficas (pp. 59-75). São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Derdyk, E. (2015). Formas de pensar o desenho. Porto Alegre: Zouk. [ Links ]

Feijoo, A. M. L. C. (2010). A escuta e a fala em psicoterapia: uma proposta fenomenológico-existencial. São Paulo: Vetor. [ Links ]

Fernandes, M. B. (2016). Psicoterapia com crianças. Em Modalidades de intervenção clínica em Gestalt-terapia (pp. 56-82). São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Ferreira, S. (1998). Imaginação e linguagem no desenho da criança. São Paulo: Papirus. [ Links ]

Holanda, A. F. (2014). Fenomenologia e Humanismo: reflexões necessárias. Curitiba: Juruá [ Links ].

Huizinga, J. (2014). Homo Ludens: o jogo como elemento da cultura. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. [ Links ]

Hycner, R. (1995). De pessoa a pessoa. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Mèredieu, F. (2006). O desenho infantil. São Paulo: Cultrix. [ Links ]

Oaklander, V. (1980). Descobrindo crianças: a abordagem gestáltica com crianças e adolescentes. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Perls, F. (1977). Gestalt Terapia explicada. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Polster, E. & Polster, M. (2001). Gestalt-terapia integrada. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Prodanov, C. C. & Freitas, E. C. (2013). Metodologia do trabalho científico: métodos e técnicas de pesquisa e do trabalho acadêmico. Novo Hamburgo: Feevale. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, J. P. (2012). Gestalt-terapia: refazendo um caminho. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, W. (2015). O que fizemos (continuamos a fazer) das crianças que um dia fomos? Brasília: Thesaurus. [ Links ]

Yin, R.K. (2009). Case study research, design and methods (applied social research methods). Thousand Oaks. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Yontef, G. M. (1998). Processo, diálogo e awareness. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Zanella, R. (2004). Brincadeira é coisa séria: atendendo crianças na abordagem gestáltica. Revista do X Encontro Goiano da Abordagem Gestáltica, 10,131-137. [ Links ]

Zanella, R. (2010). A criança que chega até nós. Em A clínica gestáltica com crianças: caminhos de crescimento. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Received: July 16, 2017

Accepted: November 02, 2017

text in

text in