Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista da Abordagem Gestáltica

versão impressa ISSN 1809-6867

Rev. abordagem gestalt. vol.27 no.2 Goiânia maio/ago. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18065/2021v27n2.1

RELATOS DE PESQUISA

Micro-phenomenology of the subjectivity of the systemic psychotherapist

Micro-fenomenologia da subjetividade do psicoterapeuta sistêmico

Micro-fenomenología de la subjetividad del psicoterapeuta sistémico

Ángela Hernández CórdobaI; Miguel Ángel Villamil PinedaII

IPsychology Doctor (Université Catholique de Louvain); Masters in Latinamerican Philosophy (Universidad Santo Tomás, Colombia); Psychologist at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Colombia). E-mail: angela.hernandez.cordoba@gmail.com

IIPhilosophy Doctor (Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia); Masters in Latinamerican Philosophy (Universidad Santo Tomás, Colombia). E-mail: miguel.villamil@usantotomas.edu.co

ABSTRACT

Systemic psychological therapy takes place in a relational context, where the subjectivities of the consultants and the therapists interact. Traditional research has focused more on the characteristics of the consultants than on the subjectivity of the therapist. Hence, "third person" perspectives have been privileged. The few studies that investigate the subjectivity of the therapist resort to introspective, interpretive and prescriptive methodologies. How to access the subjectivity of the therapist from different perspectives than those offered by "third person" observation and "first person" introspection? The purpose of the article is to explore, through the micro-phenomenological method, how the subjectivity of the therapist is shown in the first impression of a consultant. To do this, interviews were conducted with six therapists. The results show that en-active emotionality appears as an invariant of the therapist's subjectivity; and that this invariant operates as an "intelligent motivation", which enters "into action" in the course of the intersubjective relationship itself and permanently monitors and guides the therapeutic process. The results allow us to consider, on the one hand, that traditional research has undervalued the importance of en-active emotions in the therapeutic process; and, on the other, that the qualitative improvement of therapy implies not only recognizing this invariant, but also cultivating it.

Key Words: Subjectivity, Systemic therapy, Micro-phenomenology, En-active emotion, Experience

RESUMO

A terapia psicológica sistêmica ocorre em um contexto relacional, onde as subjetividades das pessoas que consultam interagem. A pesquisa tradicional se concentrou mais nas características das pessoas que consultam do que na subjetividade do terapeuta. Portanto, as perspectivas da "terceira pessoa" foram privilegiadas. Os poucos estudos que investigam a subjetividade do terapeuta recorrem a metodologias introspectivas, interpretativas e prescritivas. Como acessar a subjetividade do terapeuta sob perspectivas diferentes daquelas oferecidas pela observação em "terceira pessoa" e introspecção em "primeira pessoa"? O objetivo do artigo é explorar, através do método micro-fenomenológico, como a subjetividade do terapeuta é mostrada na primeira impressão de um consultor. Para isso, foram realizadas entrevistas com seis terapeutas. Os resultados mostram que a emocionalidade em-ativa aparece como um invariante da subjetividade do terapeuta; e que esse invariante opera como uma "motivação inteligente", que entra em "ação" no curso da própria relação intersubjetiva e monitora e guia permanentemente o processo terapêutico. Os resultados permitem considerar, por um lado, que a pesquisa tradicional subvalorizou a importância das emoções em-ativas no processo terapêutico; e, por outro lado, que a melhoria qualitativa da terapia implica não apenas reconhecer esse invariável, mas também cultivá-lo.

Palavras chave: Subjetividade, Terapia sistêmica, Micro-fenomenologia, Emoção em-ativa, Experiência

RESUMEN

La terapia psicológica sistémica acontece en un contexto relacional, donde interactúan las subjetividades de los consultantes y los terapeutas. Las investigaciones tradicionales han focalizado más las características de los consultantes, que la subjetividad del terapeuta. De ahí que hayan privilegiado perspectivas de "tercera persona". Los pocos estudios que indagan la subjetividad del terapeuta recurren a metodologías introspectivas, interpretativas y prescriptivas. ¿Cómo acceder a la subjetividad del terapeuta desde perspectivas distintas a las que ofrecen la observación en "tercera persona" y la introspección en "primera persona"? El propósito del artículo es explorar, mediante el método micro-fenomenológico, cómo se muestra la subjetividad del terapeuta en la primera impresión de un consultante. Para ello, se realizaron entrevistas a seis terapeutas. Los resultados evidencian que la emocionalidad en-activa aparece como una invariante de la subjetividad del terapeuta; y que esta invariante opera como una "motivación inteligente", la cual entra "en acción" en el trascurso de la relación intersubjetiva misma y, permanentemente, monitorea y orienta el proceso terapéutico. Los resultados permiten considerar, por un lado, que las investigaciones tradicionales han subvalorado la importancia de la emocionalidad en-activa en el proceso terapéutico; y, por otro, que el mejoramiento cualitativo de la terapia implica no sólo reconocer esta invariante, sino también cultivarla.

Palabras clave: Subjetividad, Terapia sistémica, Micro-fenomenología, Emoción en-activa, Experiencia

Introduction

The increasing demand of psychological attention after the Second World War and the dissatisfaction with the cost/benefit balance of individual psychoanalytic and behavioral therapies made easier the appearance of systemic therapy. It emerged in the United States from investigations about the dynamic of families with schizophrenic children and of disadvantaged families with children that demonstrated behavior problems. In such studies, the familiar and social interactions were weighted as the favorable contexts to the identification and resolution of psychological problems. The recognition of the empiric-positivist epistemology limitations to explain complex phenomena led to an acceptance of the systemic paradigm and the cybernetic theories as isomorphic models to differentiate the interaction of the families in which the members develop an increasing adaptive and creative ability, and in which the members experience serious difficulties to assume social life. Hence, a principle transversal to the various schools of systemic therapy is to understand the psyche as a dimension that emerges, that is built and is reconstructed in the most significant social relationships, such as the couple and the family. That is to say that, systemic psychotherapy takes care of the subjects in interactional context and it's analysis unit are the subjective worlds in permanent interaction, since it assumes that the subjects and the relationships inextricably coexist (Estupiñán; Hernández; & Serna, 2017).

Systemic psychotherapy is itself a relational context, in which there is an interaction of subjectivities of clients and therapists. Even though this is an inherent premise to the professional practice and it has always been recognized that the main tool in this job is the person of the therapist, investigations in the field have focused more on the therapeutic process and on the characteristics of the clients than in the subjectivity of the therapists (Szmulewicz, 2013). In the supervision of the cases, which is part of the training of the therapists, their personal functioning is observed and it is ensured that it is a useful instrument and not an interference or a risk for the clients (Winter & Aponte, 1987; Haber, 1990; Minuchin, Lee & Simón, 1998; Neal, 1996; Lum, 2002). In the last decades it has been investigated more directly the effects of the personal style of the therapist over the processes that he/she leads (Cheon & Murphy, 2007; Real, 1990; Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki, 2004; Carr, 2009). Those studies confirm their participation in the creation of the bond that favors the change of the clients, as well as the need to know their cognitive style and specify the confluence of the beliefs of the therapist with those of the client (Martin, Garske & Davis, 2000).

Rober (2010) has specifically focused on the subjectivity of the systemic therapist and understands that he/she resorts to images, symbols, beliefs, concepts and emotional states to initiate and develop the therapeutic process. The observations and intuitions of the therapist are the source of information that nurtures the exchange with the clients and in their internal dialogue reflects all the time about how to leverage the contents of his/her subjectivity to promote a therapeutic conversation. It's set out that in this internal dialogue a negotiation takes place between the professional role and the person of the therapist (Rober, 1999), and to explore this process there has been designed a specific supervision method. The method consists of the retrospective analysis of a case by means of the recording of the complete session, the selection of six minutes that have had a particular impression on the therapist and the textual transcription of that segment. The therapist makes a reflection about the subjective experience and his/her positioning on the case. During the group supervision, the professor and other colleagues contribute to the analysis of their experience and to the formulation of eventual connections with the therapist's personal history in a way that this process acquires an interpretative character (Rober, 2016). This author uses as a main model the internal dialogue for the study of the therapist's subjectivity since, because of his affinity to the narrative currents of systemic therapy, considers that the dialogue is the effective device for the active exchange of meanings with the clients through which the solution for the reasons of consultation emerges (Rober, 2002).

Not being unaware of the contributions of this proposal, we consider that the subjectivity of the therapist can be investigated in ways other than the internal dialogue supervised by other experts. Although dialogued introspection constitutes a source of subjective data in the "first person", it presupposes an original experience in which subjectivity, in the "first person", interacts externally with other subjectivities in the world (Vermersch, 2014). Such experience provides significant phenomenological data (such as gestures, perceptions, emotions, actions, among others) that can be described before the interpretive or prescriptive positioning of the therapist begins to operate (selection, assessment, evaluation or supervision of significant connections). Consequently, the objective of this article is to capture the subjective experience of the therapist in his/her original experience and from the "first person" perspective. For the development of this task, we will resort to the "micro-phenomenological interview" as a descriptive method of the intersubjective experience. To do this, we will focus the experience of the therapist regarding the first impression of the client.

Conceptual and methodological background

In order to understand the scope and limits of micro-phenomenology, it is important to introduce some theoretical background. According to Husserl (1990), phenomenological research emerges as a radical critique to the positivist project. In the specific field of psychology, this critique becomes patent, especially when it denounces the ingenuity of principle in which the positivist psychologist incurs: to consider that he/she can explain the subjective reality from a naturalistic objectivism and from the perspective of a disinterested observer (Villamil, 2012; 2017).

In contrast, Husserl proposes the route for a phenomenological psychology. He asserts that the first thing that is required is to clarify the topic, that is, the peculiarity of the subjectivity that becomes patent in the immediate experience. This starting point is situated by Husserl in the field of everyday experience: "It is natural and appropriate that precedence will be accorded to the most immediate types of experience, which in each case reveal to us our own psychic being." (1927, p.78). From a methodological perspective, this starting point opens up the investigation towards a series of activities or "transitions", which can be characterized as follows: a) Thematize: that implies selecting and delimiting the particular experience in the field of all psychic experience possible; b) Describe: implies giving an account of the variables of the thematized factual experience; c) Vary: implies imaginatively modifying the factual variables without affecting the essential structure of the phenomenon; d) Ideate: implies directing the attention to the core that remains invariant in the variation; e) Conceptualizing: implies making explicit the meaning of the thematized experience taking the invariant core as a base. The phenomenological psychology pursued by Husserl seeks "the all-embracing transition from the factual to the essential form, the eidos." (1927, p. 81). Thus, the psychology of the perception of bodies, for example, "will not be (simply) a report on the factually occurring perceptions or those to be expected; rather it will be the presentation of invariant structural systems without which perception of a body and a synthetically concordant multiplicity of perceptions of one and the same body as such would be unthinkable." (1927, p. 81).

The investigation proposed by Husserl supposes the introduction of two fundamental aspects; one of epistemic nature, that is, an attitude of the gaze (phenomenological attitude); and the other of an ontological nature, that is, a field of qualitative reality (the field of phenomenological reflection). It should be clarified that the reflection makes possible a field in which it's possible to go back on the lived experiences, in order to describe them, analyze them and make their meaning explicit. It should also be clarified that the gaze directed to the phenomenal field is no longer the natural corporeal vision, but the gaze of the subjectivity in the "first person", which enables "vision" in the field of the evoked experiences.

Now, this "vision" differs from introspection, like the one proposed by Rober (2010), insofar that it captures the subjectivity not as the substrate of an internal dialogue, but as the description of the sense of a correlated psychic life with the world and with other subjectivities (Husserl, 1927). In other words, the phenomenological look at subjective experiences results, according to Husserl, in the clarification of the peculiar structure or essential characteristic (eidos) of any phenomenon: "consciousness-of" and "appearance-of". Hence, the assertion that phenomena always entrails an interaction, a primordial correlation: awareness of things that appear and the appearance of things that are conscious. Therefore, the meaning of all phenomena shows two faces: "for instance, perception of something, recalling of something, thinking of something, hoping for something, fearing something, striving for something, deciding on something, and so on." (1927, p. 78). The expression that Husserl uses to make this correlation explicit is intentionality. Consequently, intentionality is an essential note of psychic phenomena. In Husserl's words: "The phenomenological reversal of our gaze shows that this "being directed" (Gerichtetsein) is really an immanent essential feature of the respective experiences involved; they are "intentional" experiences." (1927, p. 78). On the basis of these assumptions, Husserl indicates that the task of phenomenological psychology consists of:

to investigate systematically the elementary intentionalities, and from out of these [unfold] the typical forms of intentional processes, their possible variants, their syntheses to new forms, their structural composition, and from this advance towards a descriptive knowledge of the totality of mental process, towards a comprehensive type of a life of the psyche (Gesamttypus eines Lebens der See/e). (1928, p. 79).

Although Husserl's investigations have been developed by several psychological currents (Villamil & Jaramillo, 2018), it is convenient to focus the attention specifically on the analysis method called "micro-phenomenology". Phenomenology is taken up by cognitive sciences in its neurophenomenological and enactive aspect (Varela, Thompson & Rosch, 2016). In agreement with Husserl, Varela (1996) maintains that the subjectivity is irreducible to physiological nature and to the quantifiable variables. Hence, access to it requires the development of methodologies that allow, on the one hand, to systematize its qualitative data and, on the other hand, to provide a substrate that allows contrasting and complementing the subjective data against objective data from neuroscientific research, performed in a "third person" perspective. From this point of view, on the one hand, corporeity is captured as the common place in which the nervous system, the mind, subjectivity, and environmental and intersubjective interaction are "embodied"; and, on the other, phenomenology is assumed as the appropriate method for the analysis of the embodied subjectivity and as immersed in the world. Phenomenology does not have as its object the sub-personal data of neuroscience or the data from an introspective internal dialogue, but the data that emerges from evoking, in the first person, the interaction of corporeal subjectivity with other corporeal subjectivities in the world.

In the development of this enactive perspective, psychological investigations have proliferated that, in order to obtain rigorous and systematized results, introduce methodological resources taken from experimental sciences, which modify traditional phenomenology: structured interviews, step-by-step protocols, quantitative analysis of qualitative data, among others. In this context, micro-phenomenology emerges as a methodological basis of the interview of explicitation of the subjectivity. Vermesch (2012; 2014) - unsatisfied with the insufficiency of positivist tools, which only gave value to quantifiable variables - designed an interrogation method aimed at investigating the qualitative data involved in solving existential problems. From this perspective, psychotherapy is not conceived as a linear space for consultation, diagnosis and healing of a disease, but rather as an existential space in which phenomenology can operate as a "microscope" that amplifies the psychological world in order to identify "how" the problem originated and "how" its possible resolution can be directed. That is, how the subjectivity has reached to problems of suffering and stagnation, and above all, how the spiral of growth can be rekindled in clients (Estupiñán; Hernández; & Serna, 2017).

The purpose of micro-phenomenology is, on the one hand, to describe subjective experiences, focusing on their corporeal, modal and interactive character; and, on the other hand, to identify and conceptualize the qualitative invariants of the investigated experience. Thus, significant nuances of the experience are revealed that remain implicit for both introspective and third-person perspectives. (Bitbol, 2017; Petitmengin, 2017; Valenzuela and Vásquez, 2019; Vermersch, 2012; 2014).

The starting point of micro-phenomenology is the "evocation" of the subjective experience. According to Valenzuela and Vásquez (2019, p. 123), the evocation can be described as the process of coming into contact with the lived experience, remembering the sensory (visual, auditory, kinesthetic perceptions, internal sensations, etc.) and the motor (movements, muscle tone or other signs). Now, as Vermersch (2014) proposes, this starting point makes it possible to distinguish three types of interrelated lived experiences:

1. Immediate experience: it is the lived experience in a spontaneous way, for example, the experience of an emerging emotion in my cognitive activity.

2. Evoked experience: it is the lived and mediated experience, which refers to the moment when I remember the immediate experience. Therefore, 1 and 2 inform of two levels: the actual act of remembering (2) and what is remembered or the intentional object of such remembrance (1). It should be clarified that although what was remembered does not coincide "exactly" with the factual lived experience, it provides significant phenomenological data that escape the third-person perspective.

3. Reflected experience: it is the lived experience when describing the levels of the intentional acts and objects seen in the evoked experience; that is to say, the experience of analyzing, naming and making explicit 1 and 2. The reflected experience constitutes the point of arrival of micro-phenomenology in which the invariant core of the thematic experience is expressed.

In short, evocation is the starting point of micro-phenomenology, and explicit and conceptualized evocation constitutes its point of arrival. In this sense, micro-phenomenological evocation can be conceived as the transitive exercise of making contact with past experience, both sensory and motor. In this regard, Petitmengin states the following:

It is said that a person is in a state of evocation when he/she relives a past situation with the sensory and emotional dimensions that it includes, to the point that the person is more present in the past situation than in the present situation (2017, p. 5).

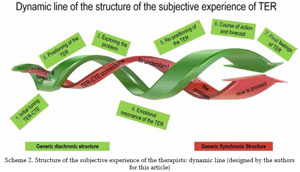

These methodological assumptions serve as the basis for the construction and analysis of the micro-phenomenological interview (Petitmengin, 2006; Valenzuela and Vásquez 2019). These tools serve as the main source for the development of this investigation. The micro-phenomenological interview consists of two analytical axes: the diachronic and the synchronic. The diachronic axis refers to the temporal development of an immediate experience (beginning, development and point of arrival). The synchronic axis refers to the focalization of the characteristics of the experience at a specific moment. Both axes are dynamic and complementary. Their flow and relationship are aimed at categorizing the invariant structure of experience, or "performative consistency", which requires to be verified in three instances: in the evoked experience, in new experiences of the same type, and in intersubjective validation by other researchers. In the verification of the results, a transversal resource called "iterative interrogation" is relevant, which consists on interrogating the data in a recurrent manner and revealing the criteria used to establish the diachronic and synchronic units (scheme 1).

The micro-phenomenological interview requires the attainment of a step-by-step procedure, which consists on the following six stages:

Data preparation: involves recording and transcribing the experience, refining the data, and selecting the text to be analyzed.

Specific diachronic analysis: involves the re-sequencing of the description, the identification of the specific diachronic units and the definition of the specific diachronic units.

Specific synchronic analysis: it involves the grouping of the statements by topic, the identification of the specific synchronic units and the definition of the specific synchronic structure.

Generic diachronic analysis: implies the alignment of the data, the identification of the generic diachronic units and the definition of the generic diachronic units.

Generic synchronic analysis: implies questioning the statements and grouping them by topic; the identification of generic synchronic units and the definition of generic synchronic structures.

Refinement of the diachronic and synchronic structures, and the elaboration of the dynamic line, which accounts for the performative consistency.

In this study, the micro-phenomenological interview was applied to six systemic therapists focusing on the first experience with the client. Let's see in detail the process carried out.

General description of the process

According to the research problem, the first step of the process was to identify and convene some colleagues who met the criteria of practicing psychotherapy in private practice. The private context was considered a very important criterion because, when therapy is carried out in institutional contexts, other factors, generally health, frequently intervene in the first contact with the clients, which may condition the first contacts between therapists and clients. Another criterion for the selection of the participants was the professional and investigative affinity in relation to their subjective work in the field of systemic therapy. Table 1 presents the age and gender characteristics of the participants in the research: they were four women and two men, aged between 30 and 70 years. These age differences imply different times of professional practice, but this variable was not controlled, given the possible difficulties in attaining the participants; rather, these differences could be a source of explanations for possible differences in the results. Regarding gender, the observation shows a female predominance in the psychotherapists' population in the local context. In relation to the clients, Table 1 presents the characteristics of gender, age and initial reason for consultation.

It should be noted that the reason for the consultation was not controlled either, but rather the therapists were left free to choose the case they wanted to evoke. The name of the reasons for consultation was given by the researchers at the end of the study, solely for the purpose of guiding the reader about the type of cases to which the therapists referred, also bearing in mind that systemic therapy addresses all kinds of difficulties and of clients. The formula proposed to the interviewees was the following: "I propose, if you agree, that you take the time necessary to get in touch with the moment when, in a first therapy session, you formed a first impression of the client, and when you have come into contact with that impression, let me know".

The interviews were in-person, except for the interview with 1E, conducted through Skype, as this therapist works in another country. Table 2 shows the duration of each interview. The times varied between 28 and 55 minutes, with an average of 41.5 minutes, according to the richness of the descriptions of the cases by each therapist and with the greater or lesser tendency to leave the evoked experience.

The reaction time of the participants was very short. In general, the emotional evocation was very intense and was combined with very vivid stories. These reactions allowed an appreciation of the strength of the evocation of the experience of the participants and to verify their commitment to the cases. Two specific difficulties in the interviews should be noted. On the one hand, there was a marked tendency for therapists to focus on the characteristics of the client and on their history, for which it was necessary to frequently reorient the evocation towards the experiences of the therapist and invite them to amplify in sensory terms the qualifiers used to describe their perceptions and experiences evoked by the case. On the other hand, it should be noted that, although the formula invites to "come into contact with a moment in which (...) you formed a first impression of the client", the therapists did not take a specific moment as a starting point. Rather, they were displaying the lived experience with the client. This way of proceeding seems to indicate that a first impression of the client refers not to a specific moment, but to the global synthesis of a process. The question then remains as to whether the formula was poorly formulated or whether it would have been pertinent to suppress the instruction of evoking a specific moment and to insist rather on how the therapist configures the impression about the client in a first session.

Finally, it should be noted that, in accordance with the guidelines for research ethics in Colombia (Statutory Law 1581 of 2012), the interviewees approved their participation and publication of the research, by signing an "Informed consent document", which details the following issues regarding the project: objectives; risks and benefits; data management; results report. The presentation and feedback of the preliminary report also served as a development of the "iterative" dynamics proposed by the micro-phenomenological method, in order to intersubjectively validate the analysis carried out. Hence, the meta-reflections of the participants have contributed to the development of the final purpose of this research about the refinement of systemic psychotherapy as such and the training of those who exercise it.

Development of the stages of the micro-phenomenological analysis

For the processing of the results, the method of micro-phenomenological analysis described by Petitmengin, Remillieux and Valenzuela-Moguillansky (2018) was followed, which, as previously stated, intends to intertwine the diachronic and synchronic dimensions of the experience to reveal its structure, through the following stages:

1. Data preparation: transcription and selection of the text to be analyzed.

One of the challenges of this work was the selection of the texts with the criterion that they included the experience of the therapists, distinguishing it from the descriptions about the clients and their reports, since as it will be seen in the results, in the transcripts and in the tables about specific diachronic and synchronic structures, that experience appears intertwined with the valuations about the persons and their stories. For this reason, there are long descriptions, in which certain information is maintained that referred to the clients, considering that in this study they constitute the context of the therapist's experience.

2. Specific diachronic analysis: re-sequencing of the description, or identification and reorganization of moments; identification of specific diachronic units; and definition of the specific diachronic structure.

It is worth remembering that, in the micro-phenomenological method, the diachronic dimension describes the temporal sequence or evolution of the space or experiential landscape of the subject through time. It could be said that, by definition, a first therapy session, regarding the context of the therapist's experience, implies a temporal sequence that takes place in the course of the conversation, where the experiences of both participants are simultaneously mobilized; therapy is in itself a process of circular feedback between therapist and client, one of whose intentions is to contribute to modify the experience of discomfort that the client brings, for which, inescapably, the therapist must react. As expressed by some interviewees, the professional knowledge of the script intended to conduct a first therapy session could be a conditioning framework of the diachrony of the experience, but, in turn, as the results show, the particularities of each therapist are evident when following that process. In order to more vividly appreciate the experience of each therapist, each phase of the diachronic structure was named after the verbatim words of the interviewees, to prevent the hasty use of generic categories that could be confused with categories of therapy theory. Likewise, taking into account the interactional nature of systemic therapy, categories were formulated that would describe the experience of the therapist in relational terms, that is, by reference to what happened when interacting with the client, and not so much as sensory experiences only focused in the therapist.

3. Specific synchronous analysis: grouping of statements by topic; identification of specific synchronic units; and definition of the specific synchronic structure.

The synchronic dimension of an experience refers to the configuration or architecture of the experiential space or landscape of a subject at a given moment. In other words, it expresses what the experience is made of. As will be further developed in the results, the raw material of the therapists' experience appeared as a continuous process constituted by: sensory perceptions about the client; emotional reactions of the therapist evoked by these perceptions; associations with references evoked from the therapists' own lives and with questions raised by the same case in the attempt to understand the problem; decisions on how to continue in the conducting of the first session to make the understanding of the problem and the consolidation of the relationship with the client more consistent; emotional reactions to the progressive understanding of the problem; decisions about the subsequent handling of the case and experience of completeness of the gaining of the client at the end of the session. This sequence would answer the research question about how the first impression of a client is configured. The names of the synchronic dimensions were also made based on the statements, in order to preserve the particularities of the experience of each therapist.

4. Generic diachronic analysis: results from the comparison of the diachronic units identified in the six analyzed cases.

According to the micro-phenomenological method, the first step of this comparison is the temporal alignment of the experiences of all the therapists, which, in this study, corresponded to the context of the first therapy session. The main grouping criterion was the thematic similarity of the phases through which the experiences of the therapists circulated, always keeping the research question as a reference through the iterative interrogation process and turning directly to the descriptions to find common themes. Special care was taken in the process of naming the diachronic units, to describe the experience of the therapists, instead of automatically falling into the concepts inherent to the theory of therapy. Table 3 shows the emerging phases and the criteria that characterize them.

5. Generic synchronic analysis: results from the comparison of the specific synchronic structures of the six therapists.

The development of this stage involved the permanent revision of the corresponding statements, in order to validate the classifications and naming, and thus visualize the emerging dynamic line as a synthesis of the structure of the therapists' experience. Table 4 presents the descriptions of the emergent generic synchronic units.

6. Refinement of the diachronic and synchronic structures: when elaborating the dynamic line, and for the sake of greater clarity, it was necessary to make adjustments and precisions about the names of the phases of the diachronic structure and about the descriptions of said phases and synchronic units.

Results

The micro-phenomenological description of the subjective experience of the systemic therapist in the first impression of the client led to the following results: firstly, the generic diachronic and synchronic structures (tables 3 and 4); second, each one of the phases of the generic diachronic structure, together with the phases corresponding to the specific structure of each therapist (table 5); third, each of the units of the generic synchronic structure, together with the specific units of each therapist (table 6); fourth, the dynamic line that accounts for the global structure of the experience (Scheme 1); and, fifth, the iteration of both the researchers and the participants. The specific structures are based on the transcripts of the interviews and on the tables that group the descriptions into moments, phases, and units of the lived experience by each therapist.

Generic diachronic and synchronic structures

Generic diachronic structure: the phases described in Table 3 synthesize the identified diachronic structure. It is convenient to remember that each phase is in itself a process that is being built in the interaction between the client and the therapist, and not just a specific moment, as can be seen in the statements of the particular phases of each therapist.

Generic synchronic structure: the units described in Table 4 identify the synchronous structure. These units provide a first approach to understanding the structure of the therapists' experience, although, as has been stated, if the semantic network of each unit were developed, its particularities and the subtleties between the subjects could be much more detailed. An attempt was therefore made to make a broad description of each unit.

It should be noted that image and contact are considered subcategories of the same unit because they both refer to the initial impression of the therapist about the client; there were differences between the therapists, so that some described more their perception of the client, others emphasized the personal experience they had faced with this perception and others alluded to both aspects.

On the other hand, it should also be noted that the therapist-client connections seem to be a kind of modulators of the intervention, that is, indications that guide the actions of the therapist in the course of the session, given that in general they preceded new appreciations about the client and their problems and to the decisions on how to continue the session. The hypotheses are conceived as connections that the therapist makes between aspects of the narrated story, the observed behavior and the references to personal events that are evoked when listening to the client's story.

Phases of the Generic Diachronic Structure and of the specific Diachronic Structures of each therapist

As appears in Tables 3 and 5, the generic phases identified were: 1) Initial therapist- client emotional attunement 2) Positioning of the therapist; 3) Reading of the problem; 4) Emotional resonance to the problem; 5) Repositioning of the therapist; 6) Line of action and prognosis; and 7) Final feelings experienced by the therapist.

[SEE TABLE ON NEXT PAGE]

Initial emotional attunement TER-CTE: The first evocation of therapists combines visual observation with proprioceptive experiences that are associated with specific emotions and reactions of pleasure, curiosity, discomfort, willingness or doubts to accept the client. The pleasant emotions tend to connect with responses of approach (generosity, gratitude, disposition and affection), while the unpleasant ones trigger questions or difficulties about that possibility (what am I up to? there is a barrier, I am unwilling and afraid).

Positioning of the therapist: These perceptions trigger a way of positioning oneself in the relationship with the client. This positioning implies the decision to accept the case or not; adopting a position that can be more or less vertical, complementary or symmetrical in the therapist- client relationship, and the choice of intervention resources to begin to explore the problem. In the findings about the positioning of the therapist, the mentions to protect, feel compassion, be moved, connect, follow the rhythm of the client, or put oneself in their shoes, are predominant. These positions set the direction that will take to the definition of the problem, which is approached with an attitude of caring for the client and the relationship that is being built with him/her.

Reading of the problem: Within the climate of care, there begins a deepening on the reasons of the clients to attend therapy and the references to which each therapist goes to put together that reading are evidenced; some bring their own experiences and all begin to appeal to categories of classification that are properly disciplinary or metaphorical (not integrating feeling, affective dependence, attachment, adaptation, halfway trip). It would seem that these definitions reflect and at the same time that they are configuring the position that the therapist will continue to assume, between care, challenge and horizontal connection, for example.

Emotional resonance in the face of the problem: The knowledge of the problem generates in the four female therapists, emotional experiences that tend to accentuate those that they already brought with them and lead to new adjustments in the relationship with the clients: "I feel fear and prudence", "I feel moved by accepting this anguished life", "solidarity, compassion and protection towards her". In the two male therapists, this phase was not identified, but the direct step to their repositioning in the relationship.

Repositioning of the therapist: The emotional resonances again fulfill the function of thermometers and indicators about how to dose the deeper exploration of the problem, with a criterion that in general seems to refer to caring for the client and protecting the relationship that is being established; It could be said that the attitude of care is also towards the therapist himself, while he/she configures a definition of the problem that gives him/her security to move forward in the case. Two types of strategies are identified: some, focused on expanding the exploration of the client's life, such as "I let her explore her world in front of me", "I play with words to expand the client's emotion", and "I insisted to open the door, but I wanted to take care of her"; others, more referred to the role of the therapist in the relationship, such as "I become more of a therapist", "I think about the diagnosis and that it is time to go slowly, but actively", "What role do I fulfill in that network?", "I get involved and I unfold my route "," We harmonize ".

Line of action and prognosis: After gaining a better knowledge of the problem, the therapists again make decisions about the course of the case. Several positions appear, consistent with the reading of the problem: "I am more prudent and I see the case as a challenge", "I am being more empathetic", "I am happy because the client discovers her own goodness", "she worries and unsettles me "," I experience fear, compassion, hope, expectation, challenge and that we have to go calmly", "I am starting a more rigorous plan ". Also in this phase the existence of resources that will begin a change in each client is recognized: "You must have resources to get out of that situation", "life can be different", "I see that the case can give good results", "she it is capable, but opaque".

Final Feelings of the therapist: Even though it was not specifically addressed with all the therapists, those who referred to this moment indicated that it had been a stimulating factor for the continuity of the therapeutic process and that it positively disposed them towards the progress of the clients: "I feel satisfied: I caught the wave of this case", "I am happy and grateful", "I felt good: it was a good date, shocking, meaningful, different".

Units of the Generic Synchronic Structure and Specific Synchronic Structures of each therapist

As shown in Table 4, four units were identified in the generic synchronic structure: 1) image and contact with the client; 2) connections between therapist and client; 3) understanding of the problem; 4) how to proceed. The dimension of image and contact is both a diachronic phase, because it is the first experience reported by therapists, and a synchronic dimension, insofar as it is a sensory and emotional impression that can arise in any of the stages of the therapy session. As shown in Table 6, it is a dimension shared by all therapists, who in the face of what they see from the client evoke diverse reactions that are located on the continuum that oscillates between distance and closeness.

[SEE TABLE ON NEXT PAGE]

In short, the synchronic structure describes what the experience of the therapists is made of when forming a first impression of the clients. According to the results, it could be said that this experience is made up of: 1) emotional reactions; 2) attitudes corresponding to calibrating the position that the therapist intuitively assumes in the relationship with the client; 3) cognitive processes such as inquiries, analysis and synthesis in order to generate comprehensive categories of a higher level of abstraction, which give a new meaning to the anecdotes and episodic stories of the client; and also constant decisions about what issues to address, which of the client's stories and reactions to react to, and what actions to propose for the continuity of the process.

All these ingredients are processed simultaneously, following the enactive flow of the therapist's experiences and appearing as reactions to sensory perceptions about the person of the client and as elaborations, where there is a circulation of appreciations, conjectures and hypotheses about the client, their problems and eventual consequences of taking a certain route in the process.

The predominant emotions, as described in the previous section, move in a wide range that goes from compassion, when the person is perceived as helpless and suffering, to fear, when the characteristics of the case make the therapist feel threatened and therefore frightened, mainly in terms of having their competencies questioned or that the results of the therapeutic process go against those expected by the family or the social context of the client. In this sense, it could be said that therapists live the therapy as a constant challenge to their abilities to satisfy expectations almost always implicit in the clients' discomfort and to strengthen the relationship as an immanent context to the therapeutic process.

A very revealing finding is the explicit awareness of the therapist about his/her position in the relationship with the client, which varies throughout the process and therefore appears as a sequence of positionings and repositionings in the diachronic analysis. Although it is completely associated with the emotional experience, in no case was the posture the automatic and linear response to the client's behavior, but it always went through the en-action, that is, through the interaction that was nuanced or strengthened according to the broader intuitions that the therapist was completing throughout the conversation. It would seem that the intention of these adjustments was always to preserve what is technically called the client's attachment to therapy, obeying the general motivation of service, moved by compassionate feelings towards the client.

Dynamic line: global structure of the experience

The relationship of the diachronic and synchronic structures allows to capture the dynamic line of the structure of the subjective experience of the systemic therapist in the first impression of the client (Scheme 1). That is, it allows to capture the "performative consistency" of the studied experience.

Although a sequence of phases can be identified in the evolution of the experience, it would be said that these phases follow a spiral route, since the therapist-client interaction permanently goes through repeated cycles that include: (1) perceptions of the therapist about the client, which awaken (2) certain emotional and cognitive connections and (3) adjustments in the positioning of the therapists, to continue in the (4) process of definitions and adjustments to the course of action, according to what emerges in the interaction with the client. The therapist passes from one phase of the sequence to another based on the intertwining of emotional and cognitive indicators, which are very difficult to separate, since each response of the client simultaneously displays those two ingredients. However, the presence of more emotional content than of traditional theories or diagnoses, underlines the weight of the emotional invariant in the uptake of the client by the therapist.

The value of the micro-phenomenological analysis through the diachronic and synchronic dimensions is precisely to allow a meticulous knowledge of an experience that takes place over a period of time and that has a specific objective, which must comply with the professional ethical requirements of a service like psychotherapy, the consequences of which will be broadened in general considerations.

The iteration of the micro-phenomenological process: feedback from the participants

The results of the micro-phenomenological analysis of the subjective experience of the therapist, synthesized in the dynamic line of experience (Scheme 1), were presented to the participants, in order to receive feedback and validate them. The metareflections and contributions of the participants served as the basis for carrying out the iteration process of the micro-phenomenological analysis, which allowed refining the addressed data in this text. Among the contributions, the following stand out: (1) they recognized the preponderant role that emotional interaction plays in the field of therapy; (2) they recognized themselves in the sequence described by the dynamic line of their subjective experience; (3) they confirmed that the evocation during the micro-phenomenological interview had been very intense; (4) stated that both the interview and the results are a powerful feedback on their therapeutic style and an important learning about their referents to carry out the help processes; (5) recognized the novelty of the research method in psychotherapy and its relevance to be applied in the training of therapists.

Final Considerations

The purpose of this article was to make explicit the subjectivity of the systemic psychotherapist, from a qualitatively different perspective from those developed by introspective and positivist approaches. For this, we described the experience of the therapist in the first impression of the client, by means of the micro-phenomenological method. This allowed us to describe, from the perspective of a "first person" involved in the world, the "dynamic line" or subjective sequence in a first session of systemic therapy, which begins with the sensory perceptions and emotional experiences evoked by the client; It continues with a position taken in the relationship with the client; progresses with a more specific exploration of the problem; continues with the therapist's repositioning before the problem; and it closes with the offer of a course of action.

This micro-phenomenological investigation makes evident the importance of the therapist's active emotionality throughout the session, insofar as it exercises a kind of permanent monitoring of the therapeutic process. The monitoring role exercised by said en-active emotionality is done on the progress of the experience and contributes to decision-making for the conduction of the therapeutic session. Now, it should be clarified that the en-active emotionality, as an ingredient of the therapist's subjectivity, is not captured as the result of an interpretive and prescriptive introspection, as proposed by Rober (2010), nor is it the result of a mediate reflection, as proposed by Husserl (1925). In other words, it does not appear as the result of an introspective, reflective or mental process, but rather as an "intelligent motivation" that enters "into action" in the intersubjective relationship itself and, from within, guides its course.

Given the importance of the en-active emotionality in the intersubjective relationship that the therapist establishes with the client, and given the rapid and simultaneous rhythm with which it operates in the course of the experience, we consider both its capture and its methodical explanation as highly relevant. In this sense, we consider that the micro-phenomenological method offers valuable resources for the development of two fundamental tasks: a synchronic and diachronic analysis of the intersubjective experience, and a characterization of the en-active emotionality as an intelligent motivation that plays a preponderant role in the "performative consistency" of said intersubjective experience. Since the micro-phenomenological method facilitates a microscopic analysis of the intersubjective experience, it makes important contributions to the understanding of therapy, of the change sought by the clients and of the training of therapists.

Therefore, we consider that the qualitative improvement of systemic therapy implies not only recognizing this emotional character, but also cultivating it. This would help to clarify the criteria used both for the identification of problems and diagnoses, and for their eventual resolutions. Thus, the emotional character is no longer seen as something to be prescribed or neutralized, and is now seen as a source of subjective meanings whose cultivation humanizes and enriches the interaction between the client and the therapist.

Although the results are not definitive, we consider that this research provides phenomenological data that significantly affect the improvement of systemic therapy; data that, from introspective or positivist perspectives, are often prescribed, undervalued, neutralized or unnoticed. This questions those contemporary perspectives that tend to reduce psychotherapy to algorithmic sequences and manuals of technical procedures, whose effectiveness is based on the illusion that it is possible to eliminate the subjectivity of therapists and clients.

Regarding the therapists'training, we consider that the application of the micro-phenomenological method opens possibilities to facilitate the self-knowledge of the therapists both in their personal and professional role. According to the interviewees, this study led them not only to reflect about their style, but also to be more aware of their emotionality, to be more appropriate and effective in the interrelation. This method could well be implemented in case supervision tasks and it would be very helpful in unblocking those cases that do not progress.

Finally, we want to thank and highlight the contribution of the participating therapists. Their contributions, both in the initial interview as and in the final feedback, challenge us to continue investigating the mysteries of intersubjective relationships, the applicability of micro-phenomenology and the improvement of the profession.

References

Anderson, H.; Goolishian, H. (1992). "The client is the expert: a not-knowing approach to therapy". In: McNamee, S.; Gergen, K. (eds). Therapy as Social Construction (pp. 25-39). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Andolfi, M., Angelo, C. and De Nichilo, M. (1989) The Myth of Atlas: Families and The Therapeutic Story. New York: Brunner/Mazel. [ Links ]

Bachelor, A. and Horvath, A. (1999) The therapeutic relationship. In M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan and S. D. Miller (eds) The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy (pp. 133-178). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Bitbol, M. (2017). "Phenoneurology". In: Constructivist Foundations 12(2)150-153. [ Links ]

Blatt, S.J., Sanislow, C.A., Zuroff, D.C. & Pilkonis, P.A. (1996). "Characteristics of Effective Therapists: Further Analyses of Data from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program". In: Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. American Psychological Association, 64,6,1276-1284. [ Links ]

Carr, A. (2009). What Works with Children, Adolescents and Adults? A Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cheon, H.S. & Murphy, M.J. (2007) The Self-of-the-Therapist Awakened, Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 19:1,1-16, http://dx.doi. org/10.1300/J086v19n01_01 [ Links ]

Di Paolo, E.; Rohde, M.; De Jaegher, H. (2010). "Horizons for the Enactive Mind: Values, Social Interaction and Play. En: Stewart, J.; Gapenne, O.; Di Paolo, E. (eds.). Enaction: Towards a New Paradigm for Cognitive Science. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 33-87. [ Links ]

Estupiñán, J., Hernández, A. & Serna, A. (2017). Transformación de la subjetividad en la psicoterapia sistémica. Bogotá: Universidad Santo Tomás. [ Links ]

Gallagher, S. y Zahavi, D. (2013). La mente fenomenológica. Madrid: Alianza. [ Links ]

Grawe, K. (2007). Neuropsychotherapy. How the Neurosciences Inform Effective Psychotherapy. Great Britain: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Haber, R. (1990). From Handicap to Handy Capable: Training Systemic Therapists in Use of Self. Family Process, 29:375-384. [ Links ]

Hoffman, L. (2002) Family Therapy: An Intimate History. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. (1925). El artículo de la Enciclopedia Británica. México: UNAM - Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas (1990). [ Links ]

Jaramillo, C.; Cabarcas, J.; Villamil, M.; Vallejo, R.; Soto, W. (2018), "El avatar: un modo de ser cibernético cualitativamente estacionario". En: Folios, 48, pp. 193-206. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17227/folios.48-8143 [ Links ]

Larner, G. (2004). Levinas: Therapy as Discourse Ethics. Chapter 2 in Strong, T. and Pare, D. Furthering Talk: Advances in the Discursive Therapies. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York. https://www.academia.edu/17978246/Levinas_Therapy_as_Discourse_Ethics [ Links ]

Lum, W. (2002). The use of self of the therapist. Contemporary Family Therapy. 24(1), March 2002. Human Sciences Press, Inc. http://www.wyomingcounselingassociation.com/wp-content/uploads/Lum-2002-Self-Of-Therapist-Satir.pdf [ Links ]

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P. & Davis, M. K. (2000) Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68:438-450. [ Links ]

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P. and Davis, M. K. (2000) Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68:438-450. [ Links ]

Minuchin, S., Lee, W.Y. & Simón, G.M. (1998). El arte de la terapia familiar. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica, S.A. [ Links ]

Neal, N.J. (1996). Narrative Therapy Training and Supervision. Journal of Systemic Therapies: Vol. 15, Special Issue on Narrative, pp. 63-78. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.1996.15.1.63 [ Links ]

Orlinsky, D. E., Ronnestad, M. H. and Willutzki, U. (2004) Fifty years of psychotherapy pro-cess-outcome research: continuity and change. In M. J. Lambert (ed.) Bergin & Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (5th edn pp. 307-389). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Orlinsky, D. E., Ronnestad, M. H. and Willutzki, U. (2004) Fifty years of psychotherapy pro-cess-outcome research: continuity and change. In M. J. Lambert (ed.) Bergin & Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (5th edn pp. 307-389). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Petitmengin, C. (2017). "Enaction as a Lived Experience towards a Radical Neurophenomenology". In: Constructivist Foundations 12(2)139-165. [ Links ]

Petitmengin, C. (2006). "Describing one's subjective experience in the second person: An interview method for the science of consciousness". In: Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 5,229-269. DOI 10.1007/s11097-006-9022-2. [ Links ]

Petitmengin, C. Remillieux, A. & Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C. (2018). "Discovering the structures of lived experience. Towards a micro-phenomenological analysis method", In: Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. DOI: doi. org/10.1007/s11097-018-9597-4 [ Links ]

Real, T. (1990). The Therapeutic Use of Self in Constructionist/Systemic Therapy. Family Process. 1990 Sep;29(3):255-72. [ Links ]

Rober, P. (1999). The Therapist's Inner Conversation in Family Therapy Practice: Some Ideas About the Self of the Therapist, Therapeutic Impasse, and the Process of Reflection. Family Process. 38:209-228. [ Links ]

Rober, P. (2002). Constructive hypothesizing, dialogic understanding and the therapist's inner conversation: some ideas about knowing and not knowing in the family therapy session. J Mar-ital Fam Ther. Oct;28(4):467-78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12382555 [ Links ]

Rober, P. (2010). The therapist's experiencing in family therapy practice. Journal of Family Therapy 1-23 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00502.x [ Links ]

Rober, P. (2010). The therapist's experiencing in family therapy practice. Journal of Family Therapy 1-23 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00502.x [ Links ]

Rober, P. (2016). Addressing the Person of the Therapist in Supervision: The Therapist's Inner Conversation Method. Family Process, 56(2). [ Links ]

Szmulewicz E., T. (2013). La persona del terapeuta: eje fundamental de todo proceso terapéutico. Rev. Chil. Neuro-psiquiatr. vol.51 no.1 Santiago mar. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S071792272013000100008 [ Links ]

Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C. & Vásquez-Rosati, A. (2019). An Analysis Procedure for the Micro-Phenomenological Interview. In: Constructitivist Foundations, 14(2),123-145. [ Links ]

Varela, F. (1992). "Autopoiesis and a biology of intentionality". In: McMullin, B. (ed.). Proceedings of the Workshop: Autopoiesis and Perception. Dublin: Dublin City University. [ Links ]

Varela, F., & Shear, J. (1999). "First-Person Methodologies: What, Why, How?". In: Journal Consciousness Studies, 6,1-14. [ Links ]

Varela, F. (1996). "Neurophenomenology: a methodological remedy for the hard problem". Journal of Consciousness Studies 3(4)330-349. [ Links ]

Varela, F. (1997). Un puente para dos miradas. Santiago. Dolmen. [ Links ]

Varela, F., Thompson, E. & Rosch, E. (2016). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Revised Edition. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Vermersch, P. (2012). Explicitation et phénoménologie: vers une psychophénoménologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Vermersch, P. (2014). "Le dessin de vécu dans la recherche en première personne: pratique de l'auto- explicitation". In: Depraz, N. (ed.). Première, deuxième, troisième personne. Paris: Zeta Books. [ Links ]

Villamil, M. (2012). "Qué, cómo y para qué de la fenomenología de Husserl". En: Rocha, A (editor). Reflexiones en Filosofía Contemporánea. Buenos Aires: Grama - Universidad San Buenaventura, 2012, pp. 235-254. [ Links ]

Villamil, M. (2017). Emociones humanas y ética. Para una fenomenología de las experiencias personales erráticas. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Villamil, M. y Jaramillo, C. (2018). "¿Se aprende fenomenología o se aprende a fenomenologizar? Implicaciones pedagógicas de la fenomenología de Husserl. En: Revista Signos, v.39, pp. 44 - 55. DOI: 10.22410/issn.1983-0378. v39i2a2018.1850 [ Links ]

Winter, J. & Aponte, H.J. (1987). The Person and Practice of the Therapist, Journal of Psychotherapy & The Family, 3:1, 85-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J287v03n01_10 [ Links ]

Received 2020.17.02

First Editorial Decision 2020.18.05

Accepted 2020.23.06

texto em

texto em