Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Pesquisas e Práticas Psicossociais

versão On-line ISSN 1809-8908

Pesqui. prát. psicossociais vol.12 no.4 São João del-Rei out./dez. 2017

ARTIGOS

Perceptions of young offenders about the police: a qualitative study conducted in Brazil

Percepções de adolescentes infratores sobre a polícia: um estudo qualitativo realizado no Brasil

Percepciones de jóvenes delincuentes sobre la policía: estudio cualitativo realizado en Brasil

Jéssica Balisardo CoelhoI; Alex Sandro Gomes PessoaII; Dorothy BottrellIII

IGraduada em Psicologia pela Universidade do Oeste Paulista e Especialista em Intervenções Psicossociais em contextos de vulnerabilidade (Unoeste)

IIPsicólogo, Licenciado em Educação Física, Mestre e Doutor em Educação pela Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) e Pós Doutor em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Docente do Departamento de Psicologia e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade do Oeste Paulista (Unoeste)

IIISenior Lecturer in the College of Arts & Education, Victoria University, Melbourne. Dorothy teaches in undergraduate and post-graduate courses in teacher education

ABSTRACT

The objective of this article is to better understand young offenders' perceptions of the police, as well as to investigate how the context of police violence is implicated in the process of criminalization of this group. A qualitative study was conducted with young offenders who have had experiences of being policed within their development contexts. From an ecological approach, we emphasize the psychosocial dimensions of adolescent experiences within a systemic model of violence. The findings highlighted the damaging effects of truculent police approaches in adolescents' lives and how such actions reinforce the social stigmas that accompany young people exposed to social exclusion, undermining the rights ensured by the Child and Adolescent Statute.

Keywords: Adolescence. Police. Young offenders. Violence. Psychosocial.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste artigo é compreender as percepções que adolescentes envolvidos em atos infracionais têm sobre a polícia, bem como averiguar como o contexto de violência policial implica no processo de criminalização do grupo supracitado. Foi realizado um estudo qualitativo com adolescentes infratores que haviam tido experiências de abordagens policiais em seus contextos de desenvolvimento. A partir de uma abordagem ecológica, enfatizamos as dimensões psicossociais das experiências dos adolescentes dentro de um modelo sistêmico. A pesquisa evidenciou os efeitos danosos das abordagens policiais truculentas na vida dos adolescentes e como essas ações reforçam os estigmas sociais que acompanham jovens em situação de exclusão social, implicando na desconsideração dos preceitos expressos nas políticas de atenção psicossocial voltadas a esse segmento.

Palavras-chave: Adolescência. Polícia. Ato Infracional. Violência. Psicossocial.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este artículo es comprender las percepciones que los adolescentes involucrados en actos infractores tienen sobre la policía, así como averiguar cómo el contexto de violencia policial implica el proceso de criminalización de este grupo. Se realizó un estudio cualitativo con adolescentes infractores que habían tenido experiencias de abordajes policiales en sus contextos de desarrollo. A partir de un enfoque ecológico, enfatizamos las dimensiones psicosociales de las experiencias de los adolescentes dentro de un modelo sistémico. La investigación evidenció los efectos dañinos de las abordajes policiales truculentas en la vida de los adolescentes y cómo estas acciones refuerzan los estigmas sociales que acompañan a jóvenes en situación de exclusión social, implicando en la desconsideración de los preceptos expresados en las políticas de atención psicosocial dirigidas a ese segmento.

Palabras clave: Adolescencia. Policía. Acto Infraccional. Violencia. Psicosocial.

Introduction

The establishment of the Child and Adolescent Statute (Brazil, 1990) brought a shift in public policy in Brazil that recognised the adolescent status of 12-18 year-olds as warranting special protections under the law. The Statute provided for the protection of adolescents from human and civil rights violations, including exploitation. Young people's rights, including "the right to life, health, nourishment, education, leisure, professional training, culture, dignity, respect, freedom, family and community life" were enshrined in a range of public policies.

Since 1990, due to their status as developing persons, adolescents who commit infractions should be included in socio-educational programs that prioritize the strengthening of community and family bonds (Brazil, 2002). This important policy change recognised the role of psychosocial opportunities for adolescents to address risk factors associated with offending. However, while the socio-educational programs may de-stigmatise adolescents caught up in the justice system, the policy focus on individual development does not address the context of violence in which adolescents are developing and how this context places adolescents at risk of criminalization.

Moreover, while there has been continuing public concern about the level of violence in many cities in Brazil, much of the public discourse remains centred on adolescent infractions and too often is concerned with assigning individual blame and giving little attention to the social and economic conditions which generate crime.

The realities for many adolescents are far from the protected and nurtured status envisaged in the policy intent. Adolescents are over represented in being victims of crime and homicide is the leading cause of death in young men aged 15-29, with the figures especially high for black and brown-skinned males growing up in peripheral and urban centres.

This article aims to contribute to better understanding of the interrelationship of psychosocial development in adolescence and contexts of violence that result in criminalization of adolescents. It discusses a small study of marginalized adolescents' own accounts of being policed. Drawing on a 'political ecology' approach, we emphasize psychosocial dimensions of adolescents' experiences within nested systems, proposed as ecologies of violence. The adolescents' troubling accounts indicate the harmful effects of police misconduct and violence and how it reinforces stigma attached to marginalized youth, in effect, undermining the psychosocial value of the Child and Adolescent Statute and its developmental provisions.

Ecologies of violence

To situate the study, we discuss the situation of marginalized adolescents using a "political ecology" framework (France, Bottrell & Armstrong, 2012). This approach to analyzing adolescent marginalization draws on Bronfenbrenner's (1979) theory of human development and understands adolescents' everyday social worlds as "a product of external 'political' forces evident at a number of levels (within microsystems, mesosystems, exosystems and macrosystems)" (France et al., 2012, p. 5). This approach recognizes the social nature of individual actions, the dialectic of social actions and social power and the interrelatedness and overlap of adolescent contexts including families, peer groups, local places and spaces, the criminal justice system, educational, community and other institutional settings. Adolescents encounter crime as its witnesses, victims and perpetrators in these interconnected systems or fields of activity. The political ecology emphasizes that activity and settings are permeated by power relations that protect, enable, regulate, control, and shape adolescents' "encounters with crime, their criminal identities and their criminal pathways" (France et al., 2012, p. 5). The macro-economic level in conjunction with the social and political systems not only influence individual lives but constitute them as social, and thus the policy effects infuse everyday individual and social experience. In the Brazilian context, the everyday activities, settings and power relations of marginalized adolescents constitute ecologies of violence.

It is important to emphasize that each individual has a history and multiple trajectories (Delgado, 2013; Rogoff, 2005) that must be understood in context. In the Brazilian and Latin American context, adolescent development occurs in nested systems influenced by historical events, economic changes, poverty, gender and ethnic issues, and social inequalities. These situations may impede the achievement of adolescents' potential and place them at risk of offending and criminalization. For instance, the possibility of reaching satisfactory levels of schooling is higher among young white females and higher income families living in the urban areas (Borges & Alencar, 2015).

At a macro-level, Brazilian adolescents, along with children, constitute the social group most affected by social, economic and violence related inequalities (Deslandes, Assis & Santos, 2005). The rates of mortality from external causes need also to be highlighted in this context. Cases of homicides involving young males is a public health issue (Borges & Alencar, 2015; Barata, Ribeiro & Sordi, 2008; Delgado, 2013; Deslandes, Assis & Santos, 2005; Feffermann, 2006; Machado & Noronha, 2002; Ruotti et al., 2014; Waiselfisz, 2015).

The reality of structural injustice present in the Brazilian context leads many adolescents to involvement in crime (e.g. robbery, drug trafficking, vandalism of public assets, and so on). These acts, even performed by adolescents, are legally characterized as criminal infractions (Brazil, 2002; Paula, 2006). Yet this characterization ignores other aspects of adolescent contexts that may not only influence their offending but also impact on their psychosocial development.

Adolescents who commit offences may seek a sense of belonging and recognition in the midst of a contradictory world that places them in a context of multiple risk factors (Pessoa, 2015). On the one hand, there is the difficulty of getting a job, to obtain satisfactory schooling processes, or to engage in normative patterns of development; on the other hand, the exposure to urban violence, social exclusion and the inequalities of opportunities may entice them toward antisocial activities (Castro, 2002; Feffermann, 2006).

Adolescents who live in this context are growing up in the midst of violence that occurs in the streets, in families, related to drug use and trafficking, exploitation and abandonment. It includes the structural and symbolic violence committed by the State through failure to guarantee basic rights and the principle of citizenship. Youth populations most subject to violence are usually located in peripheral areas, and daily exposed to situations of deprivation and disrespect (Pessoa, 2015; Delfado, 2013; Feffermann, 2006). Because of the poverty, lack of opportunities and pervasive violence, growing up in these territories, adolescents are exposed to multiple forms of social vulnerability that can propel them into illicit activities.

There is also a level of symbolic violence that intersects with the structural and micro-level violation. Elements of hegemonic discourse valorise youth subjectivities in terms of how productive they are in contributing to the country's development. Albuquerque & Costa (2016, p. 111) argue that youth have been positioned as "strategic development agents" and this discourse has circulated in national strategies for democratization, poverty reduction and economic development since the late 1980's. At the policy level, the idea of youth as vital human capital to generate prosperity may reinforce youth rights, but only if living conditions necessary for exercising rights and participating economically are guaranteed. However, consumption in many ways overrides economic participation in media and cultural discourses and young people are valorized as citizen-consumers whose success is measured by their achievement of material goods (Brook, Brook & Whiteman, 2007). It has been argued that marginalized young Brazilians are thus inserted into crime through their location in poor families and communities, barriers to education and employment and limited legitimate means of fulfilling consumer desires (Brook, Brook & Whiteman, 2007; Lucena 2016).

From this scenario of structured social disorganization, poor families and "problem youth" are seen as dangerous and police interventions are required. It is possible to observe that the characteristics of the population that is most commonly approached by the police are black people and those with low purchasing power (Caldeira, 2000; Jesus, 2016; Silva, 2014). The use of power and violence of the police reinforce distances and differences between social classes (Feffermann, 2006).

According to Pinheiro (2013), police violence opposes the expectations of its mission in a democratic society, which consists of preserving public order and playing the role of mediators of conflict. The difficulty of overcoming the legacy of military dictatorship incorporated into police training, as well as the punitive values articulated by conservative discourses in the society, are pointed out as the main reasons for the violence within policing (Caldeira, 2000; Pinheiro, 2013).

The use of violence as a common practice was evidenced in the research conducted by Machado and Noronha (2002), who investigated police abuse in a vulnerable area of the city of Salvador (Bahia state, located in North-Eastern, Brazil). Despite their recognition of discriminatory approaches by the police, the community members (study participants) defended the violent acts against those people considered 'marginal'. They made a clear differentiation between 'right people and good workers' (against whom violence is illegitimate), and the 'marginal people', judged as irrecoverable individuals (therefore, violence against them is understood as legitimate).

On the other hand, there are also studies that show the lack of confidence of the Brazilian population in the police whose actions are popularised as violent. According to Kahn (2003), the proportion of Brazilians who are more afraid of the police than of people connected with the crime is 56%. Silva and Beato (2013) found that those who had direct contact with the police, especially when the contact was compulsory or initiated by the police, were negatively affected by their level of trust in the police.

Considering the evidence of ecologies of violence, we can see how the micro-level of adolescents' everyday life intersects with and is constituted by macro-level forces. Marginalized adolescents are most vulnerable to being policed and being brought into the criminal justice system. We now turn to the study, to analyse the relationship between young offenders and the police. Unravelling the reality of these relationships may help to create policies that are more effective, as well as promote an accurate understanding of the conflicts between young offenders and the police.

Method

The aim of this study was to understand marginalized adolescents' relationship with police and their perceptions of being policed. A qualitative exploratory approach, informed by Ecological Engagement methodology (Afonso, Silva, Pontes & Koller, 2015) was employed. The researcher engaged with the participants in a program setting in order to observe and better understand adolescent realities, places and interactive processes. This qualitative approach is more open to the complexity of a phenomenon as depicted through the perspective of the participants and the meanings they attributed to their experiences (Flick, 2009).

Institutions And Participants

The research was conducted in a Reference Center Specialized in Social Assistance (CREAS) located in a mid-sized city in the inner of São Paulo state, Brazil. CREAS is a public institution linked to the National Service of Social Assistance (SUAS) that provides specialized services to families and individuals in situations of personal or social risks (victims of physical or psychological violence, abuse or sexual exploitation, homeless people, disability people, stigmatized groups, and young offenders).

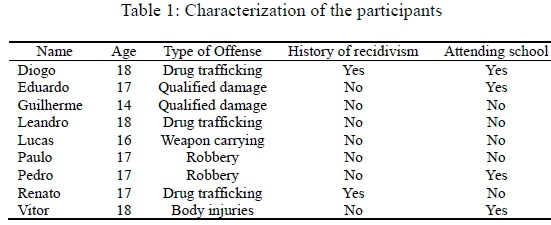

The participants of this study were nine male adolescents aged 14 to 18 years who had a history of involvement in illegal activities. They were recruited in the institution described above, and all were engaged in programs within the correctional system, known as Assisted Freedom (LA) and Community Service Provision (PSC). Table 1 presents the characterization of the participants:

Instruments, techniques and resources employed

With the consent of the Centre and all participants, the data were collected in two distinct stages. In stage 1, the first author of this article attended weekly meetings of the Reflexive Groups in which the adolescents participated at the Centre. The activities were conducted by the Centre's psychologist and aimed to develop interventions with adolescents on topics related to their infraction or the adolescent's specific situation.

Because the second phase of the research involved interviewing the participants and the content of the interview script was directly related to the adolescent's perceptions of police, it was necessary to progressively approach the participants, aiming to decrease anxiety levels, possible mistrust, and build a respectful relationship with them.

The insertion of the researcher in the group allowed the adolescents to see her as someone who was not evaluating them or who could harm them, in view of the content discussed in the group or during the formal interviews. During this stage, a field diary was used to capture the group's first experiences in discussing offending, policing and related topics. As a scientific resource for observations, the field diary was employed during the research process around everyday events at the Centre to verify relationships, behaviour patterns, and psychosocial contents, and was the basis of the researcher's early reflections (Afonso, Silva, Pontes & Koller, 2015).

After the researcher's progressive insertion in the group and with the participants' acceptance of the researcher, individual interviews were scheduled. The semi-structured interview followed a script designed to evoke informal conversation, favouring spontaneous and in-depth responses and participants' effective engagement to explore their personal values and meanings attributed to their experiences (Boni & Quaresma, 2005). The script was based on the insights presented in the literature about adolescence, crime and police. Table 2 presents the questions:

Procedures and data analysis

The interviews took place at the Centre, always after the Reflexive Group. The institution's team had assisted both in the contact with the adolescents and in the creation of bonds with the participants, inserting the researcher in the group meetings. Before the interviews, the researcher observed at least three Reflexive Group meetings involving each participant, over a two-month period. Participants were then invited to be interviewed.

Eight individual interviews were recorded by an electronic device and later transcribed in full. One participant did not authorize the recording so the notes from that interview were written up shortly after its conclusion.

The collected data were interpreted through content analysis, using techniques that obtain indicators to support the deduction and inference of knowledge through a systematic description of message content (Bardin, 1979). The analysis went through three chronological stages: 1. pre-analysis: referred to the organization of the material in order to make it operational and systematize the initial ideas; 2. exploration of the material: encompassed the moment when the raw data were distributed and aggregated in units for codification; 3. and finally, the treatment of results from inference and interpretations: allowed for the synthesis and selection of the themes, and final interpretations according to the expected objectives or with unexpected findings.

Ethical issues

Following guidelines established by the National Health Council (2012), in its resolution 466/2012, informed consent was obtained in each of the two phases (CAEE 55508716.2.0000.5515). Each interview was conducted in a comfortable room that ensured privacy. Legal guardians authorized the participation of the adolescents, and the adolescents expressed agreement with the proposed procedures and signed the Terms of Assent. The terms and vocabulary used in these documents took into account the cognitive resources of the legal guardians and adolescents. Other ethical provisions appropriate to vulnerable participants were put in place. Participants were informed they could stop the interview at any time and that they would control what they chose to disclose. There was appropriate psychology personnel available should any participant become distressed in discussing their experience. The protocol was followed for the secure storage of the data collected. Finally, it should be noted that the names of adolescents presented in this manuscript are fictitious.

Results

Content analysis revealed four central thematics about the relationship between adolescents and the police, namely: 1. Typification of police violence reported by adolescents; 2. Manifestation of prejudice, stereotypes, and social stigma; 3. Frame-up in the act; 4. Mistrust in the police. These themes were discerned from individual participants' responses and the semantic core analysed across all the interviews, as well as from the notes in the field diary used during the Reflexive Groups.

In the following sections, excerpts are presented to illustrate the main content themes that emerged in the fieldwork. Colloquial expressions that may hinder the reader's understanding were altered, though the participants' slang and vernacular expressions related to youth culture were retained. The transcriptions used for this paper were translated by the second author who is biliterate in Portuguese and English.

Reports of police violence suffered

In this thematic, we considered the different types of violence suffered by adolescents during police approaches, including ubiquitous forms of psychological and physical violence. The data show that all the interviewees reported having suffered some type of violence during the police approaches. The psychological violence occurred both in public and in private places. The Physical violence occurred in peripheral territories, when there were no other people around and usually happened in the course of the night.

The main psychological violence reported were abuse, humiliation, threats of imprisonment and death. Reports of physical violence involved the use of electric shock, pepper spray, submersion in water, punches and kicks. The following excerpts illustrate the typification of police violence suffered by the study participants.

Manifestation of prejudice, stereotypes and social stigma

We have found in this thematic that police practices in relation to adolescents are grounded in prejudice, stigma and stereotypes. Stigma is associated with negative beliefs in relation to certain groups and individuals who have been classified and labelled by others. In this study, stigma was evident in adolescents' accounts of discriminatory practices in relation to their behaviour, their appearance, the place where they live, and also what they wear. The adolescents reported constantly feeling stereotyped by the police, especially during the police approaches. When asked why they are approached by the police, they believe it is because of the clothes they wear or the way they walk, being part of particular groups, or even because the police believe that outlying neighbourhoods need a different (more punitive) approach.

Framing-up in the act

This thematic of frame-up refers to police misconduct or situations created by the police to incriminate the adolescents. The participants spoke about being framed-up in the act (most commonly "planting" drugs on victims) in the interviews, stating that there are cases of people close to them who were arrested because of frame-ups. There were also reports of frame-up cases that occurred with two participants. They reported that the police upon finding a small amount of drug, forge a greater amount to be able to justify stopping and ultimately arresting them.

Mistrust in the police

For the last thematic, excerpts are associated with the adolescents' low confidence in the police. The main reasons participants gave were: use of illicit drugs by police officers, inattention to other crimes considered more harmful to society than drug use, and the contradiction that the participants see in the role of the police who should have a protective focus on their work.

Several participants reported having seen police officers using illicit drugs, including during work hours. Thus, they questioned the effectiveness of police work to combat drugs, pointing to the hypocrisy of some police officers who allegedly seized drugs for their own use.

Participants also questioned police oversight for other crimes they consider more harmful to society than illicit drug use. For example, they cited crimes of sexual abuse, homophobia, violence against women, robbery of low-income workers and political corruption. Participants argued that anyone who is using drugs harms themselves, but not society unless they commit some other crime that harms others. They consider, therefore, that police should be more focused on tackling serious crime.

Participants further questioned what they perceived as a contradiction, pointing out that the role of police officers is to protect society, yet they do not feel protected by the police. The difference in the treatment of people with greater purchasing power, who live in urban centres or in particular condominiums was also contrasted with the relations that the police establish with families who live in peripheral areas.

There were also contrasting perceptions of police honesty. Some of the participants categorically claimed that there are no honest police officers, as they are all corrupt. Others acknowledged that there are honest police and described them as 'quieter'; but also endorsed the position that the majority of police are hostile to marginalized people.

Discussion

This study aimed to reveal the perceptions of adolescents involved in the correctional system on their experiences with the police. The thematics of their perceptions highlighted are consistent with the characterization of police violence suffered by adolescents, as found in other empirical studies with marginalized youth (Andrade, 2007; Bugnon & Duprez, 2006; Pessoa, 2015).

Police violence in Brazil is a widely known issue and has been the subject of public debate since the transition from the dictatorship period to the establishment of democratic society. Many societal groups support punitive practices, often based on traditional coercive values (Calaira, 2000; Machado; Noronha, 2002) and on media portrayals of urban violence involving adolescents as spectacle, increasing the fears of viewers who then call for more effective street policing (Delgado, 2013; Fefferman, 2006). Paradoxically, some studies point to the mistrust and fear of Brazilians regarding the police, including children and youth populations, as noted on the present research (Bugnon & Duprez, 2015; Kahn, 2003, Silva &Beato, 2013).

According to Porto (2004), the police consider that violent practices are not related to the profession itself, but are a direct response to a violent society. However, authors such as Leitão (2011) and Silva (2009) consider that the problem of police violence has its roots in military training, which reinforces a repressive view of police functions in relation to youth cultures. Military training brings combat and confrontation with the enemy as the norm, casting the city as a war zone and the citizens, especially adolescents from disadvantaged economic classes, as a potential enemy. The training received by police provides the basis for the 'police knowledge', which appears to have neither scientific basis nor human rights perspectives. It produces a way of thinking, acting, and interpreting reality in a way that naturalizes violence as acceptable practice (Jesus, 2016; Martin-Baró, 1995).

According to Cardia (2003), exposure to violence in childhood or during adolescence affects people's beliefs, values and expectations regarding the behaviour of others, alongside the likely acceptance of violence as legitimate "attitude". The accounts of young participants in the present study demonstrated how being exposed to constant police violence evoked negative beliefs, values, and expectations about the police and their work. While some adolescents accept there are "honest cops", they generally did not feel protected. Others reported total lack of trust in the police and feelings of hatred and indifference.

Cardia (2003) also shows that in places where the population has little exposure to urban violence, there is greater trust in the police, who appear more agile in attending to their needs, to manage to keep the streets calm, assist victims when necessary, and show respect in interactions. On the other hand, in places where the population is more exposed to indicators of social exclusion, the police seem to have ambiguous relationships with traffickers and use excessive force when approaching adolescents and young people.

Increased exposure to violence combined with the image of truculent police contributes to representations of the police as providing no security. The overarching message is that the laws do not protect adolescents from the periphery. Our findings clearly showed the perceived differential treatment that the residents of peripheries receive from the police compared with those who live in private condominiums or in central areas in the city. In short, according to the participants, the police are more violent and aggressive in the periphery. This conclusion may account for the adolescents' sense of mistrust of the police.

There is a social dishonour attached to poor families who live in the periphery, usually associated by the police with images of suspects and potential criminals (Jesus, 2016). For adolescents, this stigma is even stronger because in addition to residing in the periphery, they may carry the stereotypes of youth as dangerous, violent and in need of control.

Our participants believe that many police approaches are based on their appearances and the places they live in. Police approaches are considered routine in peripheral neighbourhoods and adolescents feel judged according to the clothes they wear, the way they walk and being in a 'suspicious' group. According to Andrade (2007) and Dias (2011), these personal attributes are markers of social origin and are usually associated with a series of stereotypes related to marginality. Andrade (2007) found youth reports of police discrimination that resulted in the adolescents feeling that they really are 'bad guys', which is similar to the results obtained in this study.

The findings also corroborate the research of Jesus (2016) and Bugnon and Duprez (2015), which reported situations of corruption, police extortion and cases of frame-up involving the police in the Brazilian context. There were reports of young people with involvement in drug trafficking who claim that often the police officer's goal is not to maintain public safety, but to extort money through covenants with leaders of the drug trafficking (see also Bugnon & Duprez, 2015).

In cases of frame-ups, as the classification of the crime is possession and there is no investigation of the case required, the evidence of being caught in the act is solely the narrative of the police. The accused, especially disadvantaged young people have no power to challenge the word of the police, whose role and status legitimizes their narratives related to obtaining the truth about crime (Jesus, 2016).

In the research of Bugnon and Duprez (2015) and Delgado (2013) with adolescents who were attending the correction system, there appeared feelings of the impotence of these boys in relation to prospects of justice. In the present study, this was also evidenced in accounts of being caught in the act, since the adolescents stated that they could do nothing in those situations, because it would be their word against the police officer's.

The adolescents also raised questions about the discourse on the 'war against drugs', by questioning the fate of seized drugs. They believe that in many situations police officers make personal use of drugs, in addition to storing unregistered quantities to incriminate others in cases of being caught in the act. According to Souza et al. (2013), 93.6% of military police and 66.7% civilian police consume licit drugs, while 33% of police civilians and 6.4% of the military alternate between licit and illicit substances. The authors point out that drug use is a phenomenon that happens society-wide and would not be uncommon amongst police, particularly given a risky and stressful professional daily life.

It is important to reflect on what it means to be an adolescent labelled as poor, living in the periphery, and 'known by the police'. Based on the literature, the stigmatization process can have subjective implications for adolescents. The main one, according to Andrade (2007), Dias (2011) and Leon (2007), is the social tension that discrimination can bring: the adolescent perceives the negative image that the society has about him or her and begins to feel excluded in social situations and spaces.

This tension can be the beginning of a cycle of incorporation of the stigma (Lion, 2007), whereby adolescents pay more attention to what others say about them and to assume these (pre)conceptions as their own identities, associated in some cases with the transgressive culture. In this context, adolescents find recognition and support in activities classified as antisocial, precisely because they have not found status in conventional spaces of society, including the institutions that should promote safety and sense of belonging (Pessoa, Coimbra & Koller, in press).

The adolescents presented paradoxical discourses, such as the police having their rules and the people of the neighbourhoods having to live by different ones. One of the participants even stated that reality is reversed, in which the police appear to be good, but are not, while the "bad guy" is assigned this title unfairly. Although the study has evidenced impasses that deserve more investment from the academic community, the common ground in the discourses of adolescents is that they do not believe that the police promote good social practices and their actions are permeated by violence.

Final considerations

Despite the limitations of the study, especially in relation to the size of the sample, this article provided insights into the complex relationship between young offenders and the police. The relations permeated by violence and disrespect contributed to the construction of negative representations by the adolescents regarding the police.

We noted that the adolescents who participated in the investigation did not feel that their rights were guaranteed and that the police did not constitute a protective factor in their lives. This means that the rights advocated in the National Statutes for the Protection of Children and Adolescents have not yet been successfully implemented through the national policy.

The investigation has raised other research questions for future studies concerning marginalised adolescents. It would be important to further investigate how socio-educational programs support adolescents' psychosocial development, including resilience in ecologies of violence. However, it is clear from our findings and previous research that bringing the protective policies to life requires changes at many levels. Notably, the life trajectories and social vulnerabilities that adolescents are exposed to are not considered by the police, who resort only to coercive and punitive practices against this population. The adolescents' accounts indicate that Brazil still has a policing model derived from the period of the military dictatorship that exclusively blames the adolescent for the infraction, disregards other social factors that produce this reality and actively perpetuate ecologies of violence.

Thus, we take our cue from the adolescent who spoke of reality reversal and turn the research agenda back to the police in order to further the cause of the guaranteed rights of the adolescent. We recommend further research on 1) the training of the police in relation to the approach of adolescents in peripheral regions; 2) how violent approaches are confronted within the police corps, and 3) police understanding of the engagement of adolescents in illicit activities. This research agenda could contribute to a new model of professional training of the police, supporting a focus on their acknowledgment of the rights of the youth population, as well as further understanding of negligence and violence that are part of the youth contexts.

References

Afonso, T., Silva, S. S. C., Pontes, F. A. R., & Koller, S. H. (2015). O uso do diário de campo na inserção ecológica. Psicologia & Sociedade, 27(1), 131-141. [ Links ]

Albuquerque, J. T., & Costa, M. R. (2016). Youth as strategic development agent: Between discourses and policies. Revista Katálysis, 19(1), 109-117. [ Links ]

Andrade, C. C. (2007). Entre gangues e galeras: juventude, violência e sociabilidade na periferia do Distrito Federal. (Tese de Doutorado em Antropologia Social). Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Distrito Federal. [ Links ]

Barata, R. B., Ribeiro, M. C. S. A., & Sordi, M. (2008). Desigualdades sociais e homicídios na cidade de São Paulo. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 11(1), 3-13. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1979). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Boni, V., & Quaresma, S. J. (2005). Aprendendo a entrevistar: como fazer entrevistas em Ciências Sociais. Em Tese, 2(1), 68-80. [ Links ]

Borges, L. S, & Alencar, H. M. (2015). Violências no cenário brasileiro: fatores de risco dos adolescentes perante uma realidade contemporânea. Revista brasileira de crescimento e desenvolvimento Humano, 25(2), 194-203. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Estatuto da criança e do adolescente: Lei federal nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. (2002). Rio de Janeiro: ImprensaOficial. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Brook, J. S., Brook D. W, & Whiteman, M. (2007). Growing up in a violent society: longitudinal predictors of violence in Colombian adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(1-2), 82-95 [ Links ]

Bugnon, G., & Duprez, D. (2015). As relações entre jovens infratores e a polícia sob a ótica das lógicas penais, policiais e territoriais. Revista de Ciências Sociais, 46(1), 165-198. [ Links ]

Caldeira, T. P. R. (2000). Cidade de muros: crime, segregação e cidadania em São Paulo. São Paulo: Ed. 43 / Edusp. [ Links ]

Cardia, N. (2003). Exposição à violência: seus efeitos sobre valores e crenças em relação à violência, polícia e direitos humanos. Lusotopie, s/n, 299-328.

Castro, A. L. S. Os adolescentes em conflito com a lei. (2002). In M. L. J Contini, S. H. Koller & M. N. S. Barros (Orgs.). Adolescência e psicologia: concepções, práticas e reflexões críticas (pp. 122-129). Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Federal de Psicologia.

Delgado, L. N. (2013). Os sentidos atribuídos à juventude, à violência e à justiça por jovens em Liberdade Assistida em São Paulo/SP. (Dissertação de Mestrado em Psicologia Social). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. [ Links ]

Deslandes, S. F., Assis, S. G., & Santos, N. C. (2005). Violência na adolescência: sementes e frutos de uma sociedade desigual. In Impacto da violência na saúde dos brasileiros (pp. 79-106). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde. [ Links ]

Dias, I. M. T. (2011). Estigma e Ressocialização: uma análise sobre direitos humanos e reintegração de adolescentes em conflito com a lei. Videre, 3(6), 87-109. [ Links ]

Feffermann, M. (2006). Vidas Arriscadas: o cotidiano dos jovens trabalhadores do tráfico. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa (3a ed.) Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

France, A., Bottrell, D., & Armstrong, D. (2012). A political ecology of youth and crime. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Jesus, M. G. M. (2016). "O que está no mundo não está nos autos": a construção da verdade jurídica nos processos criminais de tráfico de drogas. (Tese de Doutorado em Sociologia). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. [ Links ]

Kahn, T. (2003). Segurança pública e trabalho policial no Brasil. In Promoting Human Rights through good governance in Brazil. Centre for Brazilian Studies, University of Oxford.

Leão, N. C. (2007). Incríveis infratores: adolescentes estigmatizados em encontro com a Gestalt-Terapia. Revista da Abordagem Gestáltica, 13(1), 51-61. [ Links ]

Lucena, C. D. (2016).The phenomena of ideology and juvenile criminality. Revista Katálysis, 19, 73-80. [ Links ]

Machado, E. P., & Noronha, C. V. (2002). A polícia dos pobres: violência policial em classes populares urbanas. Sociologias, 7, 188-221. [ Links ]

Martín-Baró, I. (1996). O papel do psicólogo. Estudos de Psicologia, 2(1), 7-27. [ Links ]

Paula, P. A. G. (2006). Natureza do sistema de responsabilização do adolescente autor de ato infracional. In: ILANUD; ABMP; SEDH; UNFPA (Org.). Justiça, Adolescente e Ato Infracional: socioeducação e responsabilização. São Paulo: ILANUD. [ Links ]

Pessoa, A. S. G. (2015). Trajetórias negligenciadas: processos de resiliência em adolescentes com histórico de envolvimento no tráfico de drogas (Tese de Doutorado em Educação). Universidade Estadual Paulista, Presidente Prudente, SP, Brasil. [ Links ]

Pessoa, A. S. G., Coimbra, R. M., & Koller, S. H. (no prelo). Resiliência oculta na vida de adolescentes com histórico de envolvimento no tráfico de drogas. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, Brasília.

Pinheiro, A. S. (2013). A polícia corrupta e violenta: os dilemas civilizatórios nas práticas policiais. Sociedade e Estado, 28(2), 323-349. [ Links ]

Porto, M. S. G. (2004). Polícia e violência: representações sociais de elites policiais do Distrito Federal. Perspectiva, 18(1), 132-141. [ Links ]

Rogoff, B. (2005). A Natureza Cultural do Desenvolvimento Humano. São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Ruotti, C., Almeida, J. F., Regina, F. L., Massa, V. C., & Peres, M. F. T. (2014). A vulnerabilidade dos jovens à morte violenta: um estudo de caso no contexto dos "Crimes de Maio". Saúde e Sociedade, 23(3), 733-748. [ Links ]

Silva, D. F. (2014). Ninguém: direito, racialidade e violência. Meritum, 9(1), 67-117. [ Links ]

Silva, G. F., & Beato, C. (2013). Confiança na polícia em Minas Gerais: o efeito da percepção de eficiência e do contato individual. Opinião Pública, 19(1), 118-153. [ Links ]

Silva, J. B. (2009). A violência policial militar e o contexto da formação profissional: um estudo sobre a relação entre violência e educação no espaço da Polícia Militar do Rio Grande do Norte (Dissertação de Mestrado em Ciências Sociais). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil. [ Links ]

Souza, E. R., Schenker, M., Constantino, P., & Correia, B. S. C. (2013). Consumo de substâncias lícitas e ilícitas por policiais da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 18(3), 667-676. [ Links ]

Waiselfisz, J. J. (2015). Mapa da Violência 2015 - Mortes Matadas por Armas de Fogo. Brasília: SNJ / SEPPIR / UNESCO / FLACSO [ Links ]

Recebido em 31/08/2017

Aprovado em 20/11/2017