Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia em Pesquisa

versão On-line ISSN 1982-1247

Psicol. pesq. vol.14 no.1 Juiz de Fora jan./abr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.34019/1982-1247.2020.v14.27698

DOSSIÊ TEMÁTICO ENGAJAMENTO ESCOLAR

A funds of knowledge approach to promoting school engagement

Os fundos de conhecimento para a promoção do envolvimento escolar

Los fondos de conocimiento para promover la implicación escolar

Julie WaddingtonI; Carina SiquésII; Maria Carolà VilàIII; Maria Nieves Jimenez MorenoIV

IUniversitat de Girona. Email: julie.waddington@udg.edu

IIUniversitat de Girona. Email: carina.siques@udg.edu

IIIEscola Carme Auguet. Email: mcarola3@xtec.cat

IVEscola Carme Auguet. Email: mjime47@xtec.cat

ABSTRACT

Research shows that the exclusion of families' funds of knowledge (FoK) from the curriculum contributes to low levels of school engagement. This study is part of an ongoing research project aiming to promote school engagement among students from immigrant backgrounds through the strategic use of FoK. We provide an overview of the project design and explain how it has been implemented in the specific context of early childhood education in a school in Catalonia. A qualitative approach is used to assess the effect of the process from the teacher perspective, contrasting positive aspects with some of the difficulties experienced. We conclude that including families' FoK in pedagogical practice can contribute towards improving student engagement and fostering more inclusive educational environments.

Keywords: Funds of knowledge; Student engagement; Immigrant families; Pedagogical practice; Early childhood education.

RESUMO

Algumas pesquisas mostram que excluir os fundos de conhecimento (FoK) das famílias do currículo escolar contribui para os baixos níveis de envolvimento na escola. Este estudo é parte de um projeto de pesquisa em andamento que visa promover o envolvimento dos estudantes de origem imigrante na escola, por meio do uso estratégico do FoK. Fornecemos uma visão geral do projeto e explicamos como ele foi implementado no contexto específico da educação infantil em uma escola na Catalunha. Foi utilizada uma abordagem qualitativa para avaliar o efeito do processo pela perspectiva do professor, contrastando aspectos positivos com algumas das dificuldades vivenciadas. Concluímos que a inclusão do FoK das famílias na prática pedagógica pode contribuir para melhorar o envolvimento dos alunos e promover ambientes educacionais mais inclusivos.

Palavras-chave: Fundos de conhecimento; Envolvimento dos estudantes; Famílias imigrantes; Prática pedagógica; Educação infantil.

RESUMEN

Las investigaciones demuestran que la exclusión de los fondos de conocimiento (FoK) de las familias del currículum contribuye a bajos niveles de compromiso escolar. Este estudio forma parte de una investigación en curso destinada a promover el compromiso escolar entre alumnos de origen inmigrante mediante el uso estratégico de FoK. Proporcionamos una descripción general del diseño del proyecto y explicamos cómo se ha implementado en el contexto específico de educación de primera infancia en un centro escolar en Cataluña. Aplicamos una metodología cualitativa para evaluar el efecto del proceso desde la perspectiva del profesorado, contrastando los aspectos positivos con algunas dificultades experimentadas. Concluimos que la inclusión de los FoK de las familias en la práctica pedagógica puede contribuir a mejorar el compro miso escolar y a fomentar un entorno educativo más inclusivo.

Palabras clave: Fondos De Conocimiento; Compromiso Escolar; Familias Inmigrantes; Práctica Pedagógica; Educación En La Primera Infancia.

This paper presents results from an ongoing research project that aims to promote school engagement through the strategic use of funds of knowledge (FoK) (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005). The concept of FoK emerged in Arizona (US) in the early 1990s aiming to counteract prevailing deficit accounts which tended to be used to explain poor levels of school engagement and performance in students from working-class Latin-American families and other ethnic minority groups (Rios-Aguilar, Kiyama, Gravitt, & Moll, 2011).

The study we report on in this paper has been conducted in the context of a school with high levels of immigration on the peripheries of one of the main cities in Catalonia, Spain. Latest PISA results have highlighted how students from immigrant family backgrounds consistently perform lower and show lower levels of school engagement than their peers (OECD, 2018). In view of this, and taking into account the relevance of the FoK approach in such settings (Moll, 2014), our aim is to describe how such an approach has been implemented in a school context of high immigration, with families from different ethnic backgrounds, and to assess the effect this has on the different agents of the educational community.

Based on the results of previous research, our working hypothesis is that implementing the project will help to promote school engagement among students and their families. We take a qualitative and multifaceted approach to engagement as recommended by previous authors (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004), taking into account behavioural, emotional and cognitive aspects. One of the key principles of a Funds of Knowledge (FoK) (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005) approach to education is that, no matter where they come from and without distinction, all families have abilities and knowledge accumulated through their life practices and professional experiences. Despite this, the links or discontinuities between students' previous knowledge and school expectations and practices are different depending on the sociocultural group to which the student belongs.

Research has shown that the exclusion of families' FoK from the curriculum, and the home-school discontinuities that follow, contribute to the low levels of school engagement and poor academic performance consistently identified in students from minority groups (Civil, 2007; González, Wyman, & O'Connor, 2011; Moll, 2014). In view of this, the funds of knowledge approach emerges precisely in order to address such discontinuities and to foster a more inclusive school environment.

Within this approach, a key methodology applied to forge stronger links between home life and school life begins with ethnographic interviews carried out by teachers in their students' family homes. The aim of the interviews is to identify FoK which are significant in the lives of these families, with a view to incorporating them in school life and curricular practice. Findings from previous studies in diverse geographical contexts (Civil, 2007; Hedges, Cullen, & Jordan, 2011; Llopart & Esteban-Guitart, 2017; Llopart, Vilagran, Güell, & Esteban-Guitart, 2017) have verified the positive effects of such practice, suggesting that bridging the gap between home and school life helps to improve school engagement and render school life more meaningful for students at risk of social exclusion (Llopart & Esteban-Guitart, 2018).

In this paper we describe the design and implementation of the program in the specific domain of early childhood education, assessing the effects of this experience on the different agents of the educational community. We explain the methods used to carry out the assessment and share some of the key findings from this ongoing study. We will focus here on the effects identified from the teachers' perspective, pointing out particular strong points as well as some of the barriers faced.

Methodology

Overview of Project Phases

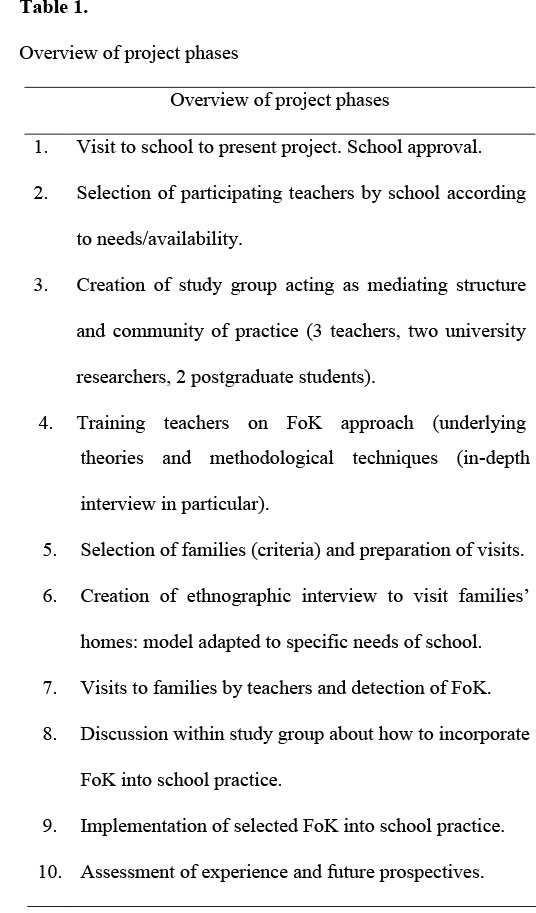

Table 1 provides an outline of the different phases of the project, starting from the initial visit at the beginning of the school year, in which the university researchers present the project to the school, and concluding with the final assessment of the experience and identification of future prospectives at the end of the year.

Project Implementation

By phase 5 of the project, the study group was well established and teachers had received initial training in the FoK approach. At this point, and after careful consideration of teacher availability and other projects carried out in the school, the participating teachers decided it would be interesting to focus their attention on newcomer families, thereby narrowing down the potential sample to families of children enrolled in P3 (the first year of the early years programme with children of 2-3 years old). Consequently, six families were selected according to different selection criteria. In the first instance, every effort was made to ensure representation from the different ethnic groups present in the school: the families selected were of Moroccan, Indian, Gambian, Honduran, and Spanish-Moroccan heritage.

Attention was also paid to the specific needs of some children, considering it appropriate to target families of children experiencing more difficulties than others adjusting to school life for different reasons: e.g. lack of required habits and boundaries, shyness. In one particular case, the high levels of immigration at the school had generated unease among one family, who had expressed their reservations prior to enrolling their child at the school: the teachers therefore decided to include this family in order to establish closer relations with them and to address any remaining reservations or concerns. Preparation work was then carried out to adapt previous interview models with scripted questions to the characteristics of these particular families. The result was the creation of a 3-step interview covering the following aspects: part 1, use of language, family history & structure; part 2, home activities & routines; part 3, parents' attitudes to education, economy, and religion.

Funds of Knowledge Detected

After explaining the project aims to families and obtaining their informed consent, teachers organised visits to their homes and conducted semi-structured interviews following the pre-prepared interview questions, while also remaining flexible and sensitive to the interests, responses and reservations expressed by the participating family members. Audio recordings were made of the interviews to facilitate their subsequent transcription, analysis and discussion. The follow-up work carried out enabled teachers to detect specific funds of knowledge which had been shown to have particular significance within the lives of the families involved: some of the FoK detected are highlighted in the word cloud provided in Figure 1.

Incorporating FoK in Classroom Practice

After completing this initial research, work was then carried out both in the study group and in teacher meetings to decide how to incorporate the FoK detected into curricular practice. One of the regular practices already established within the P3 classroom is organised under the title 'protagonist of the week' and involves different activities in which one child is the main centre of attention. Within this context, the teacher decided to invite parents to participate in the activities and to share some of the FoK detected with the class. One of the mother's interviewed (mother of the week's protagonist) was invited to show the children how to make bread. During the activity, the mother explained the ingredients used and the children were invited to join in the bread-making process. In a subsequent class session, the teacher asked the children if they remembered the ingredients used and the bread-making procedure in an activity stimulating the children's language skills, while also attending to their social, emotional and cognitive development. Comments made by the children revealed that bread-making was a common activity in many of their homes.

In another example, the children were introduced to traditional games from the country of origin of one of the other participating families. Once learned, these games became a useful strategy deployed by teachers in the classroom to activate learning processes before starting out on new or challenging educational tasks. In an example attending more to the physical and artistic development of these young children, a mother of Indian heritage came to the school in traditional costume and taught the children a typical Indian dance. The Hindu music used by the mother was recorded by the teacher and used on subsequent occasions for the children to dance to and enjoy. These are just a few of the examples of how the different FoK detected were incorporated into specific activities in the classroom which then fed into ongoing practice.

Finally, to provide an example outside this classroom-based framework, the school usually prepares a performance which is staged at the end of each school term. Having identified the dressmaking skills of one of the participating mothers during one of the home visits, they invited her to help them make the costumes for the performance. She accepted the invitation and was joined by mothers from other ethnic groups. A collaborative group emerged, and the women spent considerable time at the school during the lead up to the performance. Their dressmaking and other artistic skills were highly appreciated and made a valuable contribution to the success of the performance.

Assessing the Experience

During the final stage of the project, study group discussions concentrated on assessing the experience from the teachers' perspective. Audio recordings of these sessions were subsequently transcribed and analysed within a qualitative interpretative framework (Flick, 2006) in order to analyse the effects of the experience.

Overall, the teachers considered that the activities had enriched classroom practice by generating experiences which helped bridge the gap between home and school life and include different skills and knowledge from their students' families. The teachers had clearly applied their own pedagogical skills to ensure that activities were carried out in line with curricular standards, helping to develop linguistic, cognitive, social and emotional capacities, as well as the fine and gross motor skills which are also essential at this age.

When discussing the visits by the participating parents, the teachers referred in particular to the positive emotional effect this had on the children. According to their teachers, the children were visibly happy and very satisfied with the presence and participation of their parents in school life. Likewise, the teachers also reported similar effects on the parents, who expressed their gratitude at having been invited into the classroom to share their skills and participate in classroom activities.

However, and as highlighted by the teachers, this experience was not always easy for them, as evidenced in the following comment regarding the mother who demonstrated traditional dancing: "at first she was quite shy, but then, as she got more into the activity, she gained more and more confidence". The climate generated by these experiences strongly suggests the emergence of relations based on mutual trust and respect between teachers and families.

In this sense, and considering one of the main criteria used by the school to select the participating families, the experiences increased representation from the different ethnic groups present in the school, while also strengthening relations between these families and teachers. This was developed further in the volunteer sessions in which mothers came into the school to work on costumes and other material for the end-of-term performance. This initiative had emerged as a result of one of the visits in which the dressmaking skills of one of the mothers had been detected. While these volunteer sessions generated multiple benefits, teachers' comments highlighted two points in particular: first, that the initiative opened the door for other families who had not received visits to participate and become involved in school life; and second, that the experience strengthened relations between families from different ethnic groups who usually remained distant from each other.

Despite their differences, the women were brought together by shared interests (the well-being of their children; social integration) and a common purpose (making costumes for the school performance) within a safe environment (school) in which their contributions were valued. A comment made by one of the teachers captures the view expressed by all members of the study group: "the mothers felt really useful and empowered by having been able to contribute to one of the important activities carried out at the school".

In this way, and as expressed by the teachers, relations were not only promoted between teachers and families, but also between the families themselves. According to the teachers, and based on their past experiences working in high immigration contexts, these relations are crucial in generating an inclusive environment in which students from all backgrounds feel that they belong.

Results

Considering the overall results of the experience from the teachers' perspective, we find that the positive aspects considerably outweigh the difficult or weak aspects identified during the assessment phases, as illustrated in Table 2.

These findings support those of previous studies (Civil, 2007; Hedges, Cullen, & Jordan 2011; Joves, Siqués, & Esteban-Guitart, 2015; Reyes & Esteban-Guitart, 2013) by emphasising the positive effects derived from the process of explicitly setting out to identify the different FoK of families whose specific skills have traditionally been excluded from curricular content and practice. In the experiences described, acknowledging these skills and finding ways to incorporate them in classroom practice has had positive effects on all participants - students, teachers and families - and has enriched the educational practice developed.

Analyses of the experiences suggest that the different activities have helped to reduce discontinuities between home and school life which contribute to low levels of engagement among students from immigrant family backgrounds (Esteban-Guitart, Oller, & Vila, 2012; Esteban-Guitart & Vila, 2013; Poveda, 2001). Evidence of this is provided by teachers when commenting on the effect of bringing in activities or skills which are usually associated with home life: the teachers noted visible changes in the children and sensed that they felt more recognised and valued on seeing that these activities were appreciated and used within their school day.

Analysing the teachers' accounts further, it becomes evident that their experiences during the project have widened their perspectives and changed some of their previous views about the participating families. Not only has this helped break down stereotypes, but also to understand certain types of behaviour from a more informed and empathetic standpoint.

One aspect which surprised teachers in particular was the high level of interest shown by the families and the extremely warm reception they were given when visiting their homes. This made it evident that any assumptions that some families are not interested in their children's school lives - an assumption that sometimes arises due to the distance maintained by some families and their lack of contact with teachers - are unfounded. Instead, the teachers became acutely aware that this behaviour was due more to a lack of confidence on the part of the families and to uncertainties regarding expected behaviour. The contact established during the visits thus helped generate mutual trust, while also enabling teachers to find out more about the practices, beliefs and behaviours of these families. Apart from providing a rich source of knowledge to incorporate into their classroom practice, the teachers reported that what they learned during these encounters went beyond the specific objectives of the project and had affected them on a more personal level, prompting them to feel more committed than ever to working to foster a fully inclusive school environment and participative educational community.

Regarding some of the difficulties encountered, the findings are in line with previous studies highlighting the question of language barriers when working with families from different ethnic backgrounds (Llopart, Vilagran, Güell, & Esteban-Guitart, 2017). Nevertheless, despite the difficulties involved, teachers deployed different techniques to overcome these barriers, sometimes relying on other family members or friends to interpret for them. While this helped to establish contact, it clearly stood in the way of a more authentic and fluent flow of communication with some of the participants.

Another of the aspects reported as a weakness was the lack of time available to be able to reach more families. The satisfaction brought by observing the positive effects on the children whose families had received visits was tempered somewhat by their regret at not having been able to include all families. In view of this, they agreed to incorporate the home visits into their school protocol for welcoming newcomer families into the school. In this way, and in line with established practice in other countries (Ferguson, Bovaird, & Mueller, 2007; OECD, 2012), the school acknowledged the importance of connecting school and home, taking an active step towards promoting the active inclusion of all families.

Finally, regarding visits to the family homes, the teachers reported having learned a lot from their initial experiences conducting semi-structured interviews and adapting to the different circumstances encountered. In general, they had experienced particular discomfort when talking about the families' attitudes to economic questions in part 3 of the interview. This discomfort arose when they became more conscious of the difficult economic circumstances in which most of the families were living. As a result, the teachers concluded that they would probably omit that part of the interview from future visits and would also feel more prepared to adapt to the circumstances and be flexible in their use of the pre-prepared questions. In summary, their initial experiences had convinced them of the benefits of carrying out home visits. At the same time, the study group context had provided them with a critical space within which they could share their concerns and discuss strategies and ideas for mitigating potential difficulties in the future.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study are in line with previous research highlighting the benefits of adopting a FoK approach in contexts of high immigration and with other minority groups. The results also verify our initial working hypothesis that implementing the project would help promote school engagement among students and their families. On this latter point, we have obtained further evidence to support the need for multifaceted and qualitative approaches to defining and measuring engagement, as advocated by other researchers (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004).

In this particular case, considering children as young as 3, engagement is conceived within an ongoing and long-term perspective which also takes into account the relations established between teachers and families. On this account, establishing family-school relations from an early age is considered key to engaging students' interest in school and learning. Such relations enable teachers to identify specific skills and knowledge which will otherwise remain outside the school domain, increasing the discontinuities between home and school which have been shown to have a negative impact on students from immigrant backgrounds and other minority groups (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992).

By contrast, bringing such knowledge into the school domain impacts on students at a cognitive, behavioural and emotional level; all of which help to promote their engagement in school life and learning (Fredricks et al., 2004). On a cognitive level, carrying out work on the basis of what they are already familiar with at home invests the school work with more meaning and relevance (Chow & Cummins, 2003; Cummins, 2001; Moll & Gonzalez, 2004). On an emotional level, the impact of feeling valued and recognized (or of observing one's parents being valued and recognized) is highlighted in the findings of this study as one of the clear indicators of student satisfaction and engagement. Finally, in terms of behavioural engagement, teachers comments highlight the high level of attention paid by all children (not only the ones whose parents visited) when FoK activities were being developed in class. In summary, making classroom practice relevant and meaningful for learners, and recognizing these learners as individuals who already have, or are already familiar with, different skills and knowledge, appears to be fundamental in promoting student engagement.

One of the limitations of this study is that it has only been able to assess the effects of the project from the teacher perspective. Further studies are being conducted within this setting to assess the effects from the perspective of the participating families. It is hoped that the results of these findings will encourage other early years' practitioners to implement similar strategies to foster inclusive educational environments which take a long-term view of promoting school engagement.

Within the context of our ongoing project, other studies are being carried out in different educational and geographical contexts, assessing the effects of implementing FoK approaches with older children in both primary and secondary school contexts. These different contexts clearly impact on the way in which the projects are implemented, with care being taken to adapt the pedagogical designs to the specific needs and characteristics of the students.

One insight from the study presented in this paper points to the benefits of incorporating FoK in ongoing classroom practice, as illustrated in different examples, such as the use of music during relaxation time or the use of traditional games to activate learning. Extending this point further, while the classroom visits from parents were shown to be beneficial in this particular context, they may not be possible or even appropriate in other contexts (with older children, for example). In other words, the FoK detected can be incorporated in classroom or school practice without the corresponding family members having to be present or having to make any special visits to the school. Such questions need to be addressed within the design phase of each particular project.

In this sense, the study group format has been strongly valued by all members as a forum for sharing different perspectives and for extracting the maximum benefits from the combination of the theory-based views provided by researchers and the valuable practical experience brought by teachers. Consequently, the phases of project implementation described in Table 1 are generalizable and could be usefully applied in different contexts where similar aims are established. Thus, and while taking into account the specific characteristics of different contexts, the common goal will be to identify previously excluded FoK and design ways of incorporating them in school life to promote school engagement and foster inclusive educational environments.

Funding

This study hás been carried out within the framework of the project "Inclusión y Mejora Del Aprendizaje a través de La Contextualización Educativa. Avances en la aproximación de los Fondos de Conocimiento e Identidad (2018-2021)" EDU2017-83363-R, funded by (MINECO), State Research Agency (AEI) and (ERDF, EU).

Referências

Chow, P., & Cummins, J. (2003). Valuing multilingual and multicultural approaches to learning. In Schecter, S. R., & Cummins, J. (Eds.), Multilingual education in practice: Using diversity as a resource. (pp. 32-61). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Civil, M. (2007). Building on community knowledge: An avenue to equity in mathematics education. In Nassir, N., & Cobb, P. (Eds.), Improving access to mathematics: Diversity and equity in the classroom. (pp. 105-117). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: California Association for Bilingual Education. [ Links ]

Esteban-Guitart, M., Oller, J., & Vila, I. (2012). Vinculando escuela, familia y comunidad a través de los fondos de conocimiento e identidad. Un estudio de caso con una familia de origen marroquí. Revista de Investigación en Educación, 10(2), 21-34. Recuperado de http://reined.webs.uvigo.es/index.php/reined/article/view/148 [ Links ]

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Vila, I. (2013). Experiencias en educación inclusiva. Vinculación familia, escuela y comunidad. Barcelona: Horsori. [ Links ]

Ferguson, H. B., Bovaird, S., & Mueller, M. P. (2007). The impact of poverty on educational outcomes for children. Paediatrics Child Health, 12(8), 701-706. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.8.701 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2006). An Introduction to Qualitative research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. doi: 10.3102%2F00346543074001059 [ Links ]

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

González, N., Wyman, L., & O'Connor, B. (2011). The Past, Present and Future of "Funds of Knowledge". In Pollock, M., & Levinson, B. (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Education (pp. 481-494).

Hedges, H., Cullen, J., & Jordan, B. (2011). Early years curriculum: funds of Knowledgeas a conceptual framework for children's interests. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 185-205. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2010.511275 [ Links ]

Joves, P., Siqués, C., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2015). The Incorporation of Funds of Knowledge and Funds of Identity of Students and their Families into Educational Practice. A Case Study from Catalonia, Spain. Teaching and Teacher Education, 49, 68-77. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.001 [ Links ]

Llopart, M., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2017). Strategies and resources for contextualizing the curriculum based on the funds of knowledge approach: A literature review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 44, 255-274. doi: 10.1007/s13384-017-0237-8 [ Links ]

Llopart, M., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2018). Funds of knowledge in 21st century societies: Inclusive educational practices for underrepresented students. A literature review. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(2), 145-161. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1247913 [ Links ]

Llopart, M., Vilagran, I., Güell, C., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2017). Las visitasetnográficas a los hogares de los estudiantes como estrategia para crear lazos de confianza entre docentes y familias. Pedagogia i Treball Social. Revista de Ciències Socials Aplicades, 6(1), 70-95. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10256.4/22156 [ Links ]

Moll, L. (2014). L. S. Vygotsky and Education. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141. doi: 10.1080/00405849209543534 [ Links ]

Moll, L., & González, N. (2004). Engaging Life: A Funds of Knowledge Approach to Multicultural Education. In Banks, J., & Banks, C. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education. Second Edition (pp. 699-715). New York: Jossey-Bas. [ Links ]

OECD. (2012). Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). PISA 2015. Results in Focus. OECD Publishing.

Poveda, D. (2001). La educación de las minorías étnicas desde el marco de las continuidades-discontinuidades familia-escuela. Gazeta de Antropología, 17(31). Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10481/7491 [ Links ]

Reyes, I., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2013). Exploring multiple literacies from homes and communities. A cross-cultural comparative analysis. In Hall, K., Cremin, T., Comber, B., & Moll, L. (Eds.), International Handbook of Research in Children's Literacy, Learning and Culture (pp. 155-171). New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Rios-Aguilar, C., Kiyama, J. M., Gravitt, M., & Moll, L. (2011). Funds of knowledge for the poor and forms of capital for the rich? A capital approach to examining funds of knowledge. Theory and Research in Education, 9(2), 163-184. doi: 10.1177%2F1477878511409776 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Julie Waddington

julie.waddington@udg.edu

Recebido em: 16/08/2019

Aceito em: 25/11/2019