Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Contextos Clínicos

versão impressa ISSN 1983-3482

Contextos Clínic vol.12 no.3 São Leopoldo set./dez. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2019.123.01

ARTIGOS

Qualitative analysis of a dialectical behavior therapy adapted skills training group for women with obesity

Análise qualitativa de uma intervenção adaptada de treinamento de habilidades da terapia comportamental dialética para mulheres com obesidade

Ana Carolina Maciel Cancian; Lucas Schuster de Souza; Margareht da Silva Oliveira

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia. Avenida Ipiranga, 6681, Partenon, 90619-900, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. anacancian@gmail.com, lucas.schuster@acad.pucrs.br, marga@pucrs.br

ABSTRACT

The present study aimed to explore the perceptions about the experience of participating in an intervention based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) Skills Training. Three participants with obesity of an intervention group agree to answer a semi-structured interview two month after the group. The semi structured interview focused on three areas: (1) experience of participating in an adapted DBT protocol; (2) treatment impact; (3) helpful or unhelpful aspects. The interviews were transcribed, and a thematic analysis was performed by three independent judges to evaluate treatment outcome in the sample. The results of the thematic analysis are divided in three domains: group experience, perceived effects and skills. Participants perceived impact on interpersonal environment and personal changes in self-control, dialectic vision, self-awareness and attention to eating context. The experience of group sharing is perceived as validating, however participants also referred anxiety in the group, especially regarding learning the skills. Recommendations on conductions of Skills Training groups for this population are discussed.

Keywords: Dialectical Behavior Therapy; Qualitative Study; Obesity.

RESUMO

O presente estudo tem como objetivo explorar as percepções sobre a experiência de participar em uma intervenção adaptada do Treinamento de Habilidades da Terapia Comportamental Dialética (TCD). Três participantes com obesidade de um grupo de intervenção concordaram em responder uma entrevista semiestruturada dois meses após o término do grupo. A entrevista semiestruturada focou em três áreas: (1) experiência de participar em um protocolo adaptado da TCD; (2) impacto do tratamento; (3) aspectos que ajudaram ou não ajudaram. As entrevistas foram transcritas e uma análise temática foi conduzida por três juízes independentes para avaliar os efeitos do treinamento na amostra. Os resultados da análise temática estão divididos em três domínios: experiência no grupo, efeitos percebidos e habilidades. As participantes perceberam impactos do treinamento no ambiente interpessoal e mudanças pessoais no autocontrole, visão dialética, autoconsciência e atenção ao contexto da alimentação. A experiência de compartilhar em grupo foi percebida como validante, porém as participantes também referiram ansiedade no grupo, especialmente em relação a aprendizagem das habilidades. Recomendações para a condução de grupos de Treinamento de Habilidades são discutidas.

Palavras-chave: Terapia Comportamental Dialética; Estudo Qualitativo; Obesidade.

Introduction

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy [DBT] is an integrative clinical approach that conceptualizes problematic behaviors as attempts to regulate emotions, causing ineffective long-term effects. Studies on DBT have progressed allowing its application to different psychopathologies involving difficulties in emotional regulation (Linehan, 1993; Linehan e Wilks, 2015). Problematic eating behaviors had been conceptualized as having an emotion regulation function (Leehr et al., 2015; Zeeck et al., 2011). Evidence on DBT interventions have shown that DBT Skills Training can be effective to reduce binge eating behaviors (Telch, et al., 2001; Safer, et al., 2001; Safer, et al., 2010). Studies with obese individuals also indicate that DBT Skills Training can lessen emotional eating behaviors (Roosen, et al., 2012), improve mood and decrease binge eating (Himes et al., 2015), and help weight management clients by reducing binge eating (Musquash e McMahan, 2015). In Brazil, Cancian and colleagues (2017) found that DBT adapted Skills Training might reduce problematic eating behaviors such as binge eating in obese individuals and increase adaptive behaviors like intuitive eating. In addition, the study also found large effect sizes regarding depression symptoms in the sample, suggesting that the intervention can improve psychological conditions associated with obesity (Cancian, et al., 2017).

The skills training mode of DBT is a psychoeducational group activity with the main objective of developing self-regulation skills that do not harm the individual and his environment and allow him to have a better quality of life. Skills training is organized in four modules: Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotional Regulation, and Distress Tolerance (Linehan, 1993). Several studies have applied only the modules of mindfulness, emotion regulation and distress tolerance to samples with problematic eating behaviors (Roosen et al., 2012; Safer et al., 2010; Telch et al., 2001; Cancian et al., 2017) That choice is justified by the hypothesis that by improving emotional regulation skills the individual might be able to cope better with eating urges triggered by emotions (Safer et al., 2009).

However, the intervention outcomes are usually assessed by standardized self-report questionnaires and quantitative records of a predefined set of symptoms. Until now, no qualitative studies have been found with DBT Skills Training and problematic eating behaviors or obesity. Thus, considering the current state of the research on the application of DBT, the use of qualitative methods to investigate how these specific population undergo therapy can highlight aspects relevant to the implementation of the model. Qualitative studies enable a detailed exploration of the reality experienced by the research participants. The perspective of the individuals assessed by qualitative studies can be a complement to quantitative research (Braun e Clarke, 2014).

In the case of cultural adaptation, a qualitative exploration of the experience of participants may serve to elucidate how individuals are responding to intervention (Creswell, 2014). Some qualitative studies with DBT Skills Training were conducted with Borderline Personality Disorder users of health services (McSherry, et al., 2012; Katsacou et al., 2012) or in clinical trial participants (Barnicot, et al., 2015) have allowed the identification not only of the benefits of intervention, but also of barriers to participation in Skills Training and difficulties experienced during the process. Therefore, analyzing the experience of the participants can provide recommendations to clinicians to enrich the conduction of the original protocol, enhancing its accuracy and allowing it to precisely meet the needs of the target population.

Thus, the present study addresses the gap of a qualitative analysis of DBT implementation with a Brazilian obese sample. The aim was to explore the perspective of the participants on a DBT adapted Skills Training intervention for obese individuals, identifying obstacles, facilitators and impact.

Method

Design

The present study is a qualitative analysis of an DBT based group intervention with a Brazilian obese sample composed of three women. The participants of the present study were invited to answer a semi structured in person interview two months after the intervention. An inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze the data, as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Intervention

The present study intervention was offered as a preliminary step in a broader research on the impact of an adapted DBT Skills Training protocol for Brazilian individuals with obesity and problematic eating behaviors (Cancian, et al., 2017). All the sample participated in the same group and attended more than 75% of the intervention sessions.

The intervention was adapted from the second edition of the original DBT Skills Training protocol developed by Linehan (2015) and based on the protocol of DBT Skills Training adapted to bulimia and binge eating by Safer and colleagues (2009). The authors choose skills from the modules of Mindfulness, Emotion Regulation and Distress Tolerance, in accord to other studies with similar samples with problematic eating behaviors (Roosen et al., 2012; Safer et al., 2010; Telch et al., 2001). The present study protocol adaptation and skills is fully described elsewhere (Cancian et al., 2017).

The 10-session protocol was delivered twice a week in 2-hour sessions, conducted by a leader (Author 1) and a co-leader (Author 2). The leader was responsible for initiating group sessions, reviewing homework assignment and teaching the skills. Co-leader role was offering alternative examples and paying close attention on everyone to identify tensions and needs (Linehan, 2015).

Ethical Procedures

This research was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (CEP-PUCRS), recognized by the National Health Council (CNS) and registered with the CAEE number 50096515.0.0000.5336. All participants signed an informed consent before joining the study.

Data Collection

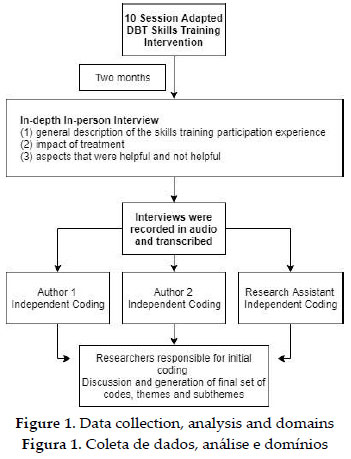

The data was collected from semi-structured interviews with the participants of the pilot group. The interviews were conducted two months after the end of the intervention, by an assistant researcher, who was not part of the team that coordinated the group. The interview topics were developed by the authors of the present study based on previous qualitative studies with DBT skills training (McSherry et al., 2012; Barnicot et al., 2015), and aimed to explore participants' perceptions about of their experiences in intervention. The interviews focused on the following areas: (1) general description of the skills training participation experience; (2) impact of the treatment; (3) aspects that were helpful and/or not helpful. Interviews were recorded with permission from the participants and later transcribed for analysis.

Data Analysis

In the epistemological perspective of this study, it was assumed that both the collection and the analysis of the data were influenced by contextual and socially constructed aspects, without, however, rejecting the possibility of shedding light on real causal mechanisms and relations (McEvoy e Richards, 2003). An inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze the data, as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). The analysis used investigator triangulation method and was examined by three independent researchers. Table 1 describes the researchers' reflexivity and possible biases in the data analysis.

To capture verbal and nonverbal elements of the interviewees' speech, the search for meanings and content patterns was performed based on transcribed text and recorded audio of the interviews. From the patterns extracted from the data, researchers generated initial codifications, which were collaboratively discussed and reformulated, generating a final set of codes and themes that comprehensively reflect the contents of the speeches as detailed in Figure 1. Finally, the researchers jointly elaborated narrative descriptions that exemplified the meaning of the themes and subthemes identified.

Results and discussion

Three domains were actively identified by the researchers from the thematic analysis of participants interviews: Group Experience (Domain 1), Perceived Effects (Domain 2) and Skills (Domain 3).

Domain 1: Group Experience

The first domain corresponds to Group Experience and concerns general aspects of the experience in the group, such as relationships with participants and leaders, emotional experiences in the group and global evaluations of the intervention. The content of this domain is divided into three main themes: Experience, Evaluation and Relationships.

Theme: Experience

The Experience theme encompasses reports about feelings and emotions experienced in the group. These experiences were divided into two-sub themes: (1) Pleasant and (2) Unpleasant. Participants described feeling comfortable in the group and feeling better after the sessions in the sub-theme Pleasant as exemplified in the statement below.

"There was this day I was having a really bad day. Then I said, "I have 500 thousand reasons and excuses not to come (to the session)", but then I got dressed and I came and then when I left the group I was feeling better. More relieved, calmer (...) The moment that we did that little breathing meditation was important. It was time to balance, to be lighter. I thought that was pretty cool" (Participant 1)

"We were at ease (in the group)." (Participant 3)

Although the participants described feeling good in general, they also referred having difficulties in the group, especially with lesson content. The sub-theme Unpleasant how those difficulties with the content impacted the motivation and reflected on the absences. Also, participants reported feeling insecure about sharing examples and having a hard time with concentration in the mindfulness exercises.

"I realized I was having a hard time, because then I missed a session, and I knew why I had missed, it was because I was not feeling comfortable (...) Yeah, I did not know if it was to be in a group (or) I think I did not understand something, and then, of course! I did not come on the other session, so I just would not understand (the skills). Then I was a little uncomfortable, not able to keep up" (Participant 3)

"I think I still have a hard time, we were trying to figure what was one bad situation "X" that happened. I think I just could not break down (all the parts of) the situation." (Participant 1)

"First thing in the group was the breathing, in that position, meditating, I used to say it was very difficult to pay attention on my breath (...) And then (the leaders asked) "Do you want to share (your example)?" and I thought to myself "should I or shouldn't I?" (Participant 1)

Theme: Evaluation

The Evaluation theme contains broad evaluative statements regarding the group and the lesson contents, without mention of specific factors or skills. The participants in general reported the group was good and useful. They referred receiving a lot of information, interconnected, in a dynamic and objective way. The data suggest that the adapted protocol was conducted in an objective and structured manner, as it was originally recommended by Linehan (1993).

"No, it was very good for me, I liked it a lot. (...) It (the group) is very dynamic, is very objective, dynamic, and I think it was very clear to me because I already participated in groups, I did therapy eight years, individual and group therapy, another approach, but I think it was very functional." (Participant 2) "It was really cool. Lots of information so, very cool." (Participant 3) "I know it's cool for you, I think for personal development and for sharing experience with everyone in the group (...) all (the content was) interconnected, I think it was useful and for different moments (...) It was very good, I liked it a lot. And it went very fast, despite having been several meetings (...) (It) was good." (Participant 1)

Theme: Relationships

Finally, the theme of Relationships comprises two sub-themes and emphasizes the perceptions of the relations of each participant with other (1) Participants and with the (2) Leaders. The interviewees mentioned a positive relationship developed with the other participants of the group in the sub-theme Participants, especially because the sharing of experiences lead to the feeling of not being alone in their problems.

"We got on well, the three of us got along." (Participant 3)

"Oh, it was great because we changed a lot of experience, right? It had different age groups, different professional backgrounds. But always with the same objective, in the end you end up understanding that your problems are so small, and people passed through the same things." (Participant 1)

However, they also compared themselves with the others and felt compelled to give opinions about the situations that other participants shared. It is recommended that participants help the person that has difficulties with the skills. Nevertheless, participants should also observe limits and be validating to one another, refraining from judging the other experiences or making unfair comparisons (Linehan, 2015). The leaders should pay attention and help the participants to realize when they crossed limits or were invalidating. The statement, given by participant 2, shows how she understood that she may feel like giving opinions but should be careful not be invalidate others.

"I do not think I could fully identify the situation (of the examples), like the girls did. They punctuated everything that was happening (in the example). I think if they punctuated 5 things, I identified 2." (Participant 1)

"... with the group it was also okay, sometimes I have to control myself not to get involved (in the examples given by other participants)." (Participant 2)

As for the sub-theme Leaders, participants perceived them as open and didactic. The stereotype of the mental health professional as someone that may be judgmental was brought by the participants in the beginning of the research. Nevertheless, the participants reported feeling the leaders were approachable and that might have reflected in feeling more comfortable to expose their difficulties as shown in the supporting quote below.

"The A. (Author 1), that, she has always pointed out (the content and examples) well, you know? Always very clear, right? And the boy also, the ... L. (Author 2). He came completing, right? (...) At first, I had some difficulty, because I have been having some

difficulty being in a group, in any group, and I explained that to A. (Author 1), right?" (Participant 3)

"And I kind of (assumed) "ah, therapists, psychologists, how are you going (to relate) (...) I had never participated in such a group program. I had already had therapy, but alone. So, I had no idea what it would be like (...) I believe they were receptive." (Participant 1)

Domain 2: Perceived Effects

The second domain corresponds to the Perceived Effects by the participants. This domain encompasses changes in behaviors attributed to intervention. Participants did not report negative or harmful effects after participating in the group and only positive aspects that came from skills training were reported. Participants developed a positive relationship with the researchers who conducted the intervention and demonstrated gratitude after the end of the protocol. Although the interview was conducted by other professional to minimize bias on responses, this may still have occurred. The domain of Perceived Effects is subdivided into two main themes: Personal Changes and Interpersonal Changes.

Theme: Personal Changes

The theme of Personal Changes is composed of four sub-themes: (1) Dialectic Vision, (2) Self-awareness, (3) Self-control and (4) Attention to the Eating Context.

The sub-theme Dialectic Vision consists of statements that show a more integrated and wide awareness and interpretation of reality, like the referred use of the skill Wise Mind. DBT mindfulness skill of Wise Mind is the integration of the opposites, emotion and rationality, reaching many ways of knowing (knowing by observing, analyzing rationally, feeling in the body and in the intuition). It refers to the individual wisdom and relates to personal values, allowing the individual to be connected with skillful means to achieve these values (Linehan, 2015). The Wise Mind is the ultimate dialectic skill. To exemplify how Wise Mind works the intervention included the story of "The Well Within", described in the manual developed by Linehan (2015). The example below, given by participant 1, shows how the story of the well helped the participant to notice that her intense emotions may be overwhelming, but the emotions are not the only part to consider when deciding how to react because it will also pass. By this example, it may be hypothesized that the distress tolerance to intense emotions and impulse control might have increased by acquiring a more dialectic vision.

"To pay more attention to the whole situation and even to the reaction, to my reaction at that moment (...) Then I remember what they said about the full well, the empty well, the distraction, the meetings. And then, how would you react. I always thought the well was full and I was going to die. But no (...) It's not the end of the world." (Participant 1)

The sub-theme of Self-awareness exemplified how participants refer to be more aware of some components of the emotions. The statement given by participant 3 shows how the evaluation of a situation can contribute to emotional arousing. In this case, she refers to be more aware of her appraisals without fusing with it. DBT skill for cognitive change is Checking the Facts. This skill addresses the appraisal of the situation by correcting assumptions, interpretations, judgments and worries, discriminating between actual observed facts or thoughts (Linehan, 2015; Neacsiu, et al., 2014).

"Because before I came here I was very paranoid about that bus stop. Very much! (...) So this is my suspicious side, so I took medicine for it, my suspicious side and my distracted side. So, these two sides I minimized by applying the technique of checking the facts." (Participant 3)

According to Gratz and Roemer (2004), a characteristic of difficulties in emotion regulation is the lack of awareness of emotion and the of the ability to label it. The emotion regulation module has specific skills to observe, describe, understand and name emotions. In the example given by participant 1, it is hypothesized that after the intervention that was a change in the ability of identifying emotions and appraisals, by applying emotions regulations skills. An improved awareness of emotions can help to change components in the model of emotions, thus changing the emotion overall.

"Even the description of feelings, because sometimes you were feeling and did not know what it was and then there was exercises and could identify (...) That's what I got the most. Kind of pay me more attention to what's going on and what triggered that situation. "Am I sad? But what triggered it? Is it the end of the world or is it not the end of the world?" (Participant 1)

The awareness of emotion is related to the sub-theme of Self-control. Characteristics of emotion dysregulation also include poor control of impulsive behaviors, resulting in difficulties to achieve non-mood-dependent goals (Neacsiu et al., 2014). Participants describe in the examples below how the increased conscience about problem situations helped them to reevaluate and refrain impulses. The ability to self-control may have increased the self-efficacy, as shown in the statement given by participant 2.

"Yes, that's right, because if I have a problem, I'll be distracted, so I would be buying things sometimes, right? Of course, I do not go out buying a car! But sometimes it's something you do not need, right? And then check the facts in that sense, "Is it necessary for me to buy this?" You know? And I started to notice more my spending, controlling more." (Participant 3)

"Yeah, it helped me a lot, it controlled me, right? (Laughs) But I really did can control myself, and it was for the best!" (Participant 2)

Both self-awareness and self-control are required to change problematic eating patterns. The sub-theme of Attention to Eating Context integrates the skills in eating situations. Mindfulness skills allow clients to identify not only harmful impulses, but also what constitutes skillful behaviors. This awareness can help individuals to break the link between emotion and problematic eating patterns, such as emotional, binge or mindless eating, regaining impulse control (Safer et al., 2009). The intervention protocol included the mindful eating practice of the raisin, adapted by Safer and colleagues (2009) from the work of Kabat-Zinn (1990). This exercise consists in instructing participants in eating a raisin with full awareness and attention to the experience of eating. The examples given by the participants relate to increased ability to taste the food, control the speed of eating, pay attention in the eating moments and diminishing the consumption of unhealthy foods, using awareness and self-control, thus practicing skill of mindful eating.

"There was also try to develop this (concentration on what you are doing) during lunch, dinner, time to eat. Because I usually eat very fast. Sometimes I'm eating too fast and I stop, or sometimes I just remember that I had to pay attention at the time when I was already eating, but then I ate too fast, I feel bad. But then I think I'm still developing it" (Participant 1)

"I'm controlling more (...) I don't eat as much as before, crappy foods (...) and when I am eating, and I started to taste the food" (Participant 2)

Theme: Interpersonal Changes

The other set of changes reported by the participants led to the theme of Interpersonal Changes, in which participants referred changes in their ways of interacting that promote feelings of well-being, satisfaction and more meaningful relationships. This theme is divided into three sub-themes, with references to different ways of relating to (1) Family Members, (2) Co-workers and (3) Other Social Groups.

The sub-theme of Family Members shows how the support of family members and close friends of the participants was identified as a facilitator for perceived improvements, in line with the findings by Barnicot et al. (2015). In addition, these results also indicate that even though the protocol did not include the module of Interpersonal Effectiveness, somehow the skills generalize to interpersonal contexts, as shown in the statement below.

"And we talk more (with the daughters), because before we fought, right, I did not have much openness because I was already taking it personally and now I can talk and I can show what I feel, so I say that I'm already taking account each side of the situation..." (Participant 2)

"With the relationships, and in the family, I became a little more tolerant." (Participant 1)

The acceptance skills also influenced participants interpersonal interaction styles. Distress Tolerance skills aim to inhibit dysfunctional impulses that interfere with long term goals, down-regulating emotional physiological arousal or altering experiential response (Neacsiu et al., 2014). In the sub-theme Co-workers, the example given by participant 1 shows how she used the Distress Tolerance skill of Half Smiling. Participants are instructed to adopt a serene and accepting face, like "accepting reality with your body" (Linehan, 2015). Controlling facial expressions has been linked with emotion regulation (Ekman, 1993).

"Now I remembered, I use a lot on the work. Wow, I'm dying of pain and such, but I'm struggling to see if I can relieve. I was even evaluated this week at work, (they said) "you are very receptive, very much, very ..." then I kept thinking "oh my God, but I do not like doing this (being receptive), what have I done?" Then I remembered: "try to smile inside, imagine that you are smiling, it will give you a relief, in the expressions, like this". I was always too blunt" (Participant 1)

The sub-theme of Other Social Groups exemplifies how the mindfulness skill of letting go of judgments can influence positively the relationship with others.

"I am more self-confident, I guess. For example, if I'm in a group of women and they all have children and so (they) talk about children, I listen, I enjoy it, different from before, that I felt inferior." (Participant 3)

Domain 3: Skills

The third domain is Skills, and encompasses perceptions related to the skills presented during the intervention, and their use in the group and generalizations outside the group. The domain is subdivided into three main themes: Use of Skills, Obstacles and Facilitators.

Theme: Use of Skills

The theme Use of Skills refers to the practice of the skills and is divided into four sub-themes: (1) Skills, (2) Crisis, (3) Routine and (4) Teaching.

The sub-theme Skills is related to the explanation or naming of skills, as exemplified in the statements below.

"I do not remember the name itself, but the question of perceiving the whole and see if it is something that has a solution, has no solution, if it has to wait a little longer and if I could deal with it from now on, immediately or in a while (...) Then I remember what they said about the full well, the empty well, the distraction..." (Participant 1)

"And there's also that one, I liked that technique of dealing with the facts, what's the name of that technique there, but it's the ... check the facts!" (Participant 3)

The sub-theme Crisis shows examples of skills use in situations of tension or instability. The statement below, given by participant 1, describe the use both Mindfulness and Distress Tolerance skills.

"Ah, if I'm angry with the traffic, I kind of take a deep breath because breathing is important, right? I remember breathing is very important, because I'm not going to get out of traffic, it's no use, I'm going to stand there, so breathe. I try to pay attention in the street, I try to do other things because otherwise it ends up being stressful (...) (They asked) "In that moment of crisis, what did you do?", "I went to take a bath." Since I live in an apartment, where would I go? I'll go and take a bath, wash the dishes, put clothes in the machine. With these attitudes I do not necessarily need, I do not know, to leave the house." (Participant 1)

In the sub-theme Routine, participants reported positive changes in their daily life after the intervention, referring integration of skills in their routine. The generalization of the skills is a necessary function of DBT (Linehan, 1993).

"I'm thinking more about things, the pros and cons, and even to eat I think I do, for example, breathing, I'm doing ... when I'm eating I realize when I eat faster, and then when I come back and taste the food, it seems like it's no longer ... you know? That thing that (I do of) feeling all the flavors ..." (Participant 2)

"I think I've been able to figure out ways to stay focused on little things. Like that, do the dishes." (Participant 1)

"So that technique of checking the facts even helped me to walk more confident in the street, connected, more confident, a healthier thing like that, within that terror that we live today, but healthier, you know?" (Participant 3)

As an example of the sub-theme Teaching, participant 2 reported how she would recommend the intervention and how she passed along the skills to a colleague. These

findings are consistent with another qualitative study of DBT Skills Training conducted by McSherry and colleagues (2012).

"And that's when I realized that everything, if I do not breathe ... And then I passed it along to my colleagues, right? Then one of them told me "I did it", because she has an attack, panic attack, then I said, I told her to come here, and then she said she started to have it (the panic attack) and then she remembered that I told her about the breathing, which she started to do and from there on she managed to control it, right? (...) And now we talk a lot, so we're talking, we're talking, and sometimes, I try to tell her "Look, think the other sides (of the situation)". She was kind of mad at a boss, (I said) "do the pros and cons" (Participant 2)

Theme Obstacles

The theme Obstacles encompasses perceptions of obstacles and difficulties faced by the participants in the practice of skills. This theme is subdivided into four sub-themes: (1) Follow-up, (2) Revision, (3) Invalidating Environment. Respondents reported in the sub-theme Follow-up that they wished they had booster sessions after the end of the intervention, to review and deepen the themes worked through new practices, exercises and examples. Moreover, the absence of a closer follow-up was perceived by the participants as an obstacle to the use of the training.

"If it had another group, I would want to participate again. For the depressives, the fatties, I know it's cool for you, I think for personal development and for sharing experience with everyone in the group." (Participant 1)

"...but without being accompanied I find it difficult to apply these techniques." (Participant 3)

In the sub-theme of Revision, participants statements exemplified the need to revise the skills, and difficulty to remember some skills. Considering the perceived need for more training, it can be hypothesized that the duration of the training might have been too brief for an effective learning of some skills.

"I said to myself I need to review (the material), is that I get a lot in a race, but I thought about reviewing everything, all those activities to continue and not lose it and be always working, following it (...) but I think there are a lot more things there that can work, but I think I have to dominate well, to dominate one situation well to go to another, I don't know..." (Participant 2)

"It's just that I would have to remember all the skills, review all the material and I did not do that, right?" (Participant 3)

The sub-theme Invalidating Environment summarizes perceptions about environments that do not reinforce or encourage the use of skills.

"I think they did not notice, actually I think they only notice when we are in a crisis. When it is a good thing they do not acknowledge, but when in a crisis is the first thing they notice" (Participant 1)

Yeah, but things are like this, I get lightheaded when I am deprived, when someone do me wrong I get fragilized, especially when it comes from my mother, because my mother is extremely harsh (...) it wears me out, I get (pause) fragile, she always has something bad to say" (Participant 3)

Theme Facilitators

The last theme, Facilitators, is related to the contexts that validate the use of skills and inner aspects that stimulate the continuation of the use. This theme is composed of two sub-themes: (1) Psychotherapy and (2) Family Support. The sub-theme Psychotherapy exemplifies how the individual therapy component help to stay more focused, which corroborates Linehan's (1993) proposal for complementarity between individual therapy and group training.

"...they referred me to therapy, so I'm doing therapy, and I feel it is centralizing me ..." (Participant 2)

The sub-theme of Family Support shows how the care provided by close relatives and friends can play a role of a validating environment, consistent with the theoretical DBT model of biosocial theory (Linehan, 1993).

"Yes, yes, so I tell them (the daughters), but I do not speak in a fighting voice tone right, so I tell that, something I did not like, something like that, and they promptly understand. (...)And so it is, I think it was very good." (Participant 2) "So when I'm talking to a sister that I get along really well, it is very good. My sister-in-law gets on very well too, we treat ourselves as sisters all of us, this is much better, and they support me, my sister and my sister-in-law are the people who give me the emotional support" (Participant 3)

Conclusion

Qualitative studies present a unique perspective of the participants about the experience; however, the present study raises some possible implications of these findings and suggestions for future research and clinical practice.

"Eye on the Prize"

It is noteworthy that the present study tailored an adapted Skills Training intervention for obese participants, but the results on weight and eating contexts were identified only on one sub-theme. Participants identified broader implications of the training, which might indicate that they generalized the skills, but also that they did not practice or learned enough to apply on all relevant dieting and exercise contexts. For tailored interventions, the group leaders might have to be especially aware to "keep the eye on the prize", that is to try to constantly link the skills with the client goals of managing problematic eating behaviors, actively asking for participants examples and adhering to treatment protocol (Safer et al., 2009).

The Importance of the Co-leader Role

Participants related the experience of apprehension in the group. There are similar findings regarding the experience of anxiety in participating in Skills Training, and that might be a potential risk for treatment abandonment (Barnicot, et al., 2015). Therefore, these results reinforce the need of constant monitoring of participants reactions and feelings during training, seeking effective identification of moments in which the experience becomes aversive to participants, a role mainly attributed to the co-leader (Linehan, 2015). Thus, the co-leader role is not secondary. It might be the key to enable the leaders to promptly act, reducing the chance of abandonment, especially considering that many participants present difficulties with emotional regulation and tend to avoid unpleasant feelings. Besides preventing treatment interruption, attention to aversive emotional experiences in the group can create opportunities to practice the skills (Barnicot et al., 2015; Linehan, 2015).

Conducting Skills Training in Groups

Participants referred the positive impact of the group on the experience of the intervention, especially feeling normalized by hearing the other participants examples. Similar results have been found in other group studies with Skills Training regarding the share of experiences. Participants report feeling normalized and validated, perceiving the group environment as a facilitator of positive changes (Barnicot et al., 2015; McSherry et al. 2012). Authors from the field of group therapy like Yalom and Leszcz (2006), stress that the universality is the therapeutic factor that encompasses the perception that human experiences are shared, and that in exposing their problems, the individual may feel less isolated and experience greater intimacy and a sense of belonging. Although the Skills Training is not a group therapy, it seems that these results indicate that the therapeutic factor of universality is also present in this context. This is related to the experience of validation that results from the interaction between participants of the skills training, as described by Linehan (2015). The experience of recognition and the development of a supportive interpersonal context is one of the advantages that gives support to the orientation of conducting skills training in groups (Linehan, 2015).

Importance of the Interpersonal Context and Generalization of the Skills

The results indicate that the participants perceived positive impacts in day to day relationships, even though the intervention did not include the Interpersonal Effectiveness Skills Training module. All the themes identified included perceptions about relationships: how participants felt about each other and the leaders, impact on interactions with family, co-workers and other groups and how their interpersonal environment can facilitate or obstacle the use of skills. These results might reflect the generalization of the skills to the interpersonal context. Indeed, the ability of effectively regulate emotions can impact how one relate with the environment (Linehan, 1993). Also, difficulties with emotional regulation built up from invalidating relationships can lead to the maintenance of problematic interpersonal relationship styles (Linehan, 1993). Participants reported that gaining more control over their emotional reactions influenced the improvement observed in their interpersonal relationships, which was also evidenced by McSherry (2012). Thus, the development of a more adaptive repertoire of emotional regulation strategies might influence the acquisition of more effective styles of interacting with other people and promote a sense of confidence and satisfaction that was observed in the speeches of the participants. In line with the results found by Barnicot and colleagues with Borderline Personality Disorder individuals (2015), the present study also stress the importance of an validating environment as a facilitator to skills use. That might support that not only individuals with pervasive emotion dysregulation are negatively impacted by invalidations and benefit from validation interactions.

Metaphors and Exercises as a Learning Tool

Participants referred that the protocol was didactic, but also complex and sometimes overwhelming, mentioning the need of follow up sessions, revisions, and psychotherapy. However, participants also could assess the use of skills, and it is hypothesized that metaphors and exercises helped participants to learn and remember the skills. A story like "The Well Within" helped a participant to assess her Wise Mind. Breathing exercises, Half Smile Distress Tolerance skill and Mindfulness exercises were remembered, used and even taught to others by the participants, and these skills were practiced with the leaders in the protocol sessions. Therefore, it might be interesting that

Skills Training leaders develop a lot of stories, metaphors and practical exercises to each skill taught, aiming to improve the memorization and learning of skills.

Limitations of the current study are similar to more general limitations of qualitative research. The sample size was small, limiting the generalisation of the results to a broader population. Although participants were interviewed by an independent researcher this may still have affected how they spoke about their experiences, leading to a positive bias. Finally, the authors background may have affected how data was analysed, due to research experience and previous knowledge about Dialectical Behavior Therapy. All authors have a background as clinical psychologists, and that certainly impacts how the study was designed and the data was perceived.

In conclusion, the thematic analysis of the participants' interviews indicate that the protocol was well accepted by the participants and is shown to be feasible in the Brazilian context with a sample of obese women. This study brings unique perceptions about the experience of participating in a Skills Training protocol that draws possible directions for future studies.

References

BARNICOT, K.; COULDREY, L.; SANDHU, S.; PRIEBE, S. 2015. Overcoming barriers to skills training in borderline personality disorder: A Qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE, 10:1-15. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140635 [ Links ]

BRAUN, V.; CLARKE, V. 2014. What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 9:9-10. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152 [ Links ]

CANCIAN, A.C.M.; DE SOUZA L.A.S.; LIBONI, R.P.A.; MACHADO, W.L.; OLIVEIRA, D.S. 2017. Effects of a dialectical behavior therapy-based skills group intervention for obese individuals: a Brazilian pilot study. Eating and Weight Disorders. doi: 10.1007/s40519-017-0461-2. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 29197947. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. 2014. Investigação Qualitativa e Projeto de Pesquisa: Escolhendo entre Cinco Abordagens. 3. ed. Porto Alegre, Penso, 342 p. [ Links ]

EKMAN, P. 1993. Facial Expression and Emotion. American Psychologist, 48:384-392. [ Links ]

GRATZ, K. L.; ROEMER, L. 2004. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36:41-54. [ Links ]

HIMES, S. M.; GROTHE, K. B.; CLARK, M. M.; SWAIN, J. M.; COLLAZO-CLAVELL, M. L.; SARR, M. G. 2015. Stop regain: a pilot psychological intervention for bariatric patients experiencing weight regain. Obesity surgery, 25(5):922-927. [ Links ]

KABAT-ZINN, J.1990. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness: the program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York, Dellacorte Press, p.453. [ Links ]

KATSAKOU, C.; MAROUGKA, S.; BARNICOT, K.; SAVILL, M.; WHITE, H.; LOCKWOOD, K.; PRIEBE, S. 2012. Recovery in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): A Qualitative Study of Service Users' Perspectives. PLoS ONE 7(5):1-8. Recuperado de: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0036517&type=printable [ Links ]

LENZ, A. S.; TAYLOR, R.; FLEMING, M.; SERMAN, N. 2014. Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy for treating eating disorders. Journal of Counseling and Development, 92:26-35. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00127.x [ Links ]

LINEHAN, M. 1993. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, Guilford Press, p. 558. [ Links ]

LINEHAN, M. 2015. DBT skills training manual. 2. ed., New York, Guilford Press, p. 504. [ Links ]

LINEHAN, M.; BOHUS, M.; LYNCH, T. R. 2007. Dialectical behavior therapy for pervasive emotion dysregulation: Theoretical and practical underpinnings. In: J. J. GROSS (Ed), Handbook of emotion regulation New York, NY: Guilford Press, p.581-605.

MCEVOY, P.; RICHARDS, D. 2003. Critical realism: a way forward for evaluation research in nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43:411-420. Recuperado de: http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02730.x [ Links ]

NEACSIU, A.; BOHUS, M.; LINEHAN, M. 2014. Dialectical behavior therapy: An intervention for emotion dysregulation. Handbook of emotion. Recuperado de: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marsha_Linehan/publication/284982382_Dialectical_behavior_therapy_skills

_an_intervention_for_emotion_dysregulation/links/56a99e5808aeaeb4cef95bf9.pdf [ Links ]

ROOSEN, M. A.; SAFER, D.; ADLER, S.; CEBOLLA, A.; VAN STRIEN, T. 2012. Group dialectical behavior therapy adapted for obese emotional eaters; a pilot study. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 27(4):1141-1147. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.4.5843. [ Links ]

SAFER, D. L.; ROBINSON, A. H.; JO, B. 2010. Outcome from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Group Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy Adapted for Binge Eating to an Active Comparison Group Therapy. Behavior Therapy, 41:106-120. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.006 [ Links ]

SAFER, D.L.; TELCH, C.F.; CHEN, E.Y. 2009. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, Guilford Press, p. 244. [ Links ]

SAFER, D. L.; TELCH, C. F.; AGRAS, W. S. 2001. Dialectical behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158:632-634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.632 [ Links ]

YALOM I. D.; LESZCZ M. 2006. Psicoterapia de grupo: teoria e prática. 5. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2006. 528 p. [ Links ]

Submetido em: 03.04.2018

Aceito em: 07.12.2018