Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho

versão On-line ISSN 1984-6657

Rev. Psicol., Organ. Trab. vol.20 no.4 Brasília out./dez. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.4.03

Employees and supervisors perceptions of human resource practices in different types of organizations over a lifespan

Percepções de funcionários e supervisores sobre as práticas de recursos humanos em diferentes tipos de organizações ao longo da vida

Percepciones de empleados y supervisores sobre las prácticas de recursos humanos en diferentes tipos de organizaciones en función de la edad

Esther VillajosI ; Núria TorderaII

; Núria TorderaII ; Laura LorenteIII

; Laura LorenteIII

IUniversidad Internacional de Valencia, Spain

IIUniversitat de València, Spain

IIIUniversitat de València, Spain

Information about corresponding author

ABSTRACT

Organizations and age management are key factors for achieving sustainable workplaces and careers. Thus, it is important to understand how different types of organizations deliver Human Resource (HR) practices to employees at different stages of life and how those employees perceive them. Therefore, the present study aims to analyze age differences in the implementation and perception of HR practices in three organizational types (social, public, and for-profit). Three age groups were considered (employees under 35, from 35 to 50, and over 50 years). HR practices were measured as reported by 159 managers (implemented practices) and by their 1524 employees (perceived practices). Separated ANOVAs were conducted to test hypotheses. Results show significant differences among age groups, showing support for three different models of age management in different organizational types.

Keywords: HR practices, age management, organizational type.

RESUMO

As organizações e a gestão da idade são fatores-chave para alcançar empregos e carreiras sustentáveis. Portanto, é importante entender como diferentes tipos de organizações fornecem práticas de Recursos Humanos (RH) para funcionários em diferentes fases da vida e como esses funcionários as percebem. Assim, o presente estudo tem como objetivo analisar as diferenças de idade na implementação e percepção das práticas de RH em três tipos de organizações (social, pública e com fins lucrativos). Foram consideradas três faixas etárias (empregados menores de 35 anos, de 35 a 50 anos e maiores de 50 anos). As práticas de RH foram medidas conforme relatado por 159 gestores (práticas implementadas) e por seus 1524 funcionários (práticas percebidas). Foram conduzidas ANOVAs separadas para testar hipóteses. Os resultados mostram diferenças significativas entre as faixas etárias, oferecendo suporte para três modelos distintos de gestão de idade em diferentes tipos de organizações.

Palavras-chave: práticas de Recursos Humanos, gestão de idade, tipo organizacional

RESUMEN

Las organizaciones y la gestión de la edad son factores clave para lograr lugares de trabajo y carreras sostenibles. Por lo tanto, es importante comprender el tipo de prácticas de Recursos humanos que ofrecen las organizaciones a empleados en distintas etapas de la vida y cómo las perciben esos empleados. Por lo tanto, el presente estudio tiene como objetivo analizar las diferencias de edad en la implementación y percepción de las prácticas de RR.HH. en tres tipos organizacionales (social, pública y con fines de lucro). Se han considerado tres grupos de edad (empleados menores de 35, de 35 a 50 y mayores de 50 años). La muestra está compuesta por 159 gerentes y sus respectivos empleados (1524) que reportaron las prácticas implementadas y percibidas respectivamente.Se realizaron ANOVAs separados para poner a prueba las hipótesis. Los resultados muestran diferencias significativas entre los grupos de edad, mostrando apoyo para tres modelos diferentes de gestión de la edad en diferentes tipos de organizaciones.

Palabras clave: prácticas de Recursos Humanos, gestión de la edad, tipo de organización

Societies worldwide are facing important and diverse challenges, most of them related to the sustainability of human and social life. Among them, age-related demographic changes have an important impact in how social and organizational life is conceived and designed, including key questions such as the sustainability of the public pension system or age management in organizations.Data from the most recent World Population prospects signals that by 2050, one in six people in the world, and one in four in Europe, will be over 65 years old (UN, 2019), and the number of those between the ages of 55 to 64 years, is expected to increase by approximately 16,2% (9.9 million) between 2010 and 2030 (Ilmarinen, 2012).This acceleration of global aging is also affecting geographical areas such as Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia where this process is expected to occur in the forthcoming years at an even higher rate (UN, 2019). At the same time, the tendencies in the participation of older adults in the workforce are not evolving equally around the world. For instance, in Latin America the participation of older workers in the labor market is decreasing (Queiroz, 2017), following a tendency previously found in more developed economies (Peiró et al, 2012). This tendency has been reversing in the last years and the employment rate of older workers between 55 and 64 years old in the last decade, has increased in Europe from 44.1% to 59.1% (mean for the 27 EU countries) (Eurostat, 2019). In this context, there is a worldwide debate pending regarding the implications of increasing the retirement age, and the participation of older citizens in the labor market.

Thus, the demographic challenge led by the increase in the proportion of the oldest population, and the mean age and age diversity in the work context has urged many institutions around the world (as OECD, Eurofound, OIT), to focus on the concept of sustainable work over a lifespan. Despite the ambiguity of the term, sustainable work has been defined as "achieving living and working conditions that support people in engaging ways, and remaining in the work force throughout an extended working life" (Eurofound, 2020), thus emphasizing the importance of the quality of work and working conditions over the different stages of life. The pursuit of sustainable work includes the implication of many different stakeholders, from institutional and political levels (e.g. H2020), to individuals, and individual decisions regarding career development (Van der Heijden & De Vos, 2015).

For instance, the European Union, through its European Agency for Safety & Health at Work, dedicates its energy to reaching that objective by promoting policies for active ageing, and the employability and work ability during a lifespan, emphasizing the design of health-promoting workplaces. Also, policies from national governments include several strategies such as flexible retirement policies, equal treatment in employment, solidarity between generations, or removal of disincentives in hiring older workers (Berlin et al., 2016), in order to help to sustainably manage ageing.

International and local governments, however, cannot address these challenges without counting on cooperation from organizations. They are a central element in the equation for the development of sustainable work and careers (Tordera et al, 2020). Organizations manage the incorporation, maintenance, and exit of employees through their Human Resources (HR) policies and practices. Indeed, HR practices have been found to be a central function in organizational life (Boxall & Purcell, 2011), and are positively related to employees performance (Huselid, 1995), well-being, and self-development (Van de Voorde & Boxall, 2015; Villajos et al., 2019a). They are considered to have a strong influence on the development of sustainable careers directly and indirectly (De Vos et al., 2020). HR practices directly impact career sustainability because they can create opportunities for career progression, self-development, and maintenance; but they can also affect employees indirectly by helping them to develop their abilities and skills for managing their own career. Moreover, different authors have pointed out that sustainable work requires the adaptation of HR practices to the different needs that employees have over a lifespan (Tordera et al., 2020).

However, despite the expected efficacy of HR practices for enhancing different aspects of sustainable careers such as employability, workability, or career support (De Prins et al., 2015), different voices have protested the inequality of HR practices for workers in organizations at different ages and career stages (Kordošová et al., 2014; OLoughlin et al., 2017). Research has previously acknowledged that organizations all over the world generally adopt a depreciation model related to an HR management system, which is oriented to the detriment of older workers (Peiró, et al., 2013). Indeed, research at the organizational and macro level has suggested that investments in workers are mostly evident at the first stages of their careers and very limited in the last stages. However, not much research has considered how this is perceived by the employees themselves, or the people in charge of delivering those practices. In this sense, research could benefit from a more employee-centered approach that considers not only how the organizations report the practices to be implemented, but also how they are perceived (Van de Beuren et al., 2020).

HR management research has generally been conducted in for-profit organizations and mostly in Anglo-Saxon countries (Gantman et al., 2015). However, the economic reality goes beyond these types of organizations, and it is necessary to consider this phenomenon in different realities and contexts, such as public or social enterprises, to appreciate its applicability (Den Hartog et al., 2004). These three different types of organizations have different values, goals, and different "ways" of conducting business that has an influence on how they manage ageing employees.Private or for-profit companies, public organizations and social enterprises have different goals, values and management perspectives. In this context, it is important to analyze how organizations are designing their actual HR management policies, and to identify the potential gaps or failures for a successful age management. Only in doing so, can workers be correctly assisted at different stages of ageing. This can help governments analyze, or implement and promote, public policies addressed to different realities.

Therefore, the goal of this study is to analyze age differences in the implementation and perception of HR practices in different types of organizations. In order to do this, HR practices for three different age groups (less than 35 years old, between 35 and 50 years old, and older than 50) in three different organizational types (social, public and for-profit organizations) will be analyzed, including the differences between two distinct points of view: what employees perceive they are offered, and what supervisors say the organizations are implementing.

The Importance of HR Practices During a Lifespan

HR practices are the tools to regulate the relationship between employees and organizations, and are key elements for building human capital, and achieving employee and organizational goals (Bello-Pintado, 2015; Jiang et al., 2012). Several research studies and meta-analysis show that HR practices have a positive effect on employees well-being and performance (e.g., Rauch & Hatak, 2016). HR practices provide employees with useful resources, and employees in turn reciprocate by showing positive attitudes and behaviors in their work. The Job Demands-Resource model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) can help explain the demands and resources that employees need in every stage of their life. In fact, Liebermann and colleagues (2013) modified this model into the "Working Life Span Demands-Resources model" to incorporate age as a moderator that affects both job demands and job resources, the interaction of which can have an impact on how long employees remain in their jobs. This can help practitioners to understand better age management.

It is possible to identify different types of HR practices as well as different taxonomies. HR practices are in-line with the strategy of the organization (Guest et al., 2004) and it is important to note that the implementation of HR practices may be different depending on the organizational setting or the target group. Furthermore, employees perceptions about practices may vary, and a gap between managers aims and employees perceptions may appear (Liao et al., 2009).

An important aspect to consider when designing and implementing these practices, is employees age, since it influences the aforementioned job demands and resources model and may be detrimental for successful ageing at work (Kooij et al., 2014; Veth, 2016). For example, studies on career stages suggest that age-related changes in motivational variables play a key role in positive work outcomes for middle-age and older workers. Therefore, it is important to design jobs for people in different stages of life to ensure that they continue to be motivated and productive throughout their working life. According to the person-environment fit perspective (Perry et al., 2012), the level of compatibility among people and their work environment affects their attitudes and behaviors, and this fit may change with age, with respect to their needs and motivations. In this respect, lifespan theories such as the Selection Optimization and Compensation Model (SOC) and Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) have acknowledged the impact of age on employees motivation, goals and job-related well-being. This highlights the value of age management, maintaining that age-related factors (or even other diversity factors) should be taken into consideration in management, policies and practices, and acknowledge the importance of adopting a sustainable approach to career management to guarantee this, even though most HR practices are focused on younger employees in the first stages of their careers (Lytle et al., 2015). In fact, supervisors often discriminate against employees by age when offering HR practices, lowering organizational equality (Kooij et al., 2012). In this sense, the focus is needed to include the entire workforce and not just a limited number of employees (De Prins et al., 2015).

HR Models for Age Management and the Perception of HR Practices

Regarding how organizations may structure their practices for age management, two different models have been identified: the maintenance and the depreciation models (Hedge et al., 2006; Yeatts et al., 2000). The depreciation model assumes that employees reach their highest value when they are at the early stages of their careers; they come to a plateau during middle age; and afterwards, their value begins to steadily decline, until they reach retirement age. This model has been the basis for HR management for years and concentrates on the losses related to the aging process without paying much attention to potential gains. On the contrary, the maintenance or conservation model considers workers at any career stage or age, as valuable assets for the organization. From this perspective, the adequate investments in training and management of human resources are responsible for the value that those employees report to the organization.

Research has also pointed out that some HR practices could be more useful than others for employees depending on age. Drawing on theories of lifespan, some authors have differentiated groups of HR practices that could better suited to the specific needs and motives of employees at different stages in their lives (Kooij, et al. 2013, Looij et al., 2014). More concretely, Kooij et al., 2013, distinguished between HR maintenance and development practices. HR maintenance practices help workers sustain their performance in spite of age-related factors. HR development practices aim to help workers improve their performance. In their research, Kooij et al., found that the association between development practices and well-being weakened with age. However, the association between maintenance practices and well-being and between development practices and performance, strengthen with age.

There is some evidence showing that the depreciation model is prominent worldwide (Peiró et al., 2013), so that, in general terms, fewer HR practices are offered to employees as they age.In this sense, research has pointed out some examples such as the lack of effort in designing practices to maintain older workers in organizations (OECD, 2006), the reduced number of recruitment and hiring practices targeting older workers (Manpower, 2007), or the prevalence in general of age discrimination in the workplace (AARP, 2019). However, most of this research has been mainly developed at the macro level and there is a need to study the potential differences in how employees at different life and career stages are offered, perceive and/or experience the HRM system.

Research has developed different approaches to the measurement of HR practices and systems. In a recent review, Boon et al. (2019) distinguish between different levels of analysis depending on who is the key informant, differentiating between intended, implemented and perceived HR practices. When HR managers report on HR practices, this information usually reflects the intended policies of the organizations - what the organizations plan to do. Managers and supervisors are generally the ones in charge of delivering the HR practices and so they are key informants for the implemented practices, what indeed is finally being offered. Finally, when employees are asked to report on HR practices, they can provide information about how those practices are experienced and perceived by the key targets of those actions. The difference between intended or implemented, and perceived or experienced HR practices is evident (Woodrow & Guest, 2014). This means that the way employers design or intend to implement HR practices can be different from how employees perceive or experience them, and in fact, previous research has acknowledged these differences (Beijer, 2014; Liao et al., 2009).

All these different approaches might be valid, but their appropriateness depends on the type of research questions presented. As Villajos et al. (2019b) pointed out, although relying on managers perceptions of HR practices is important for the organizational design, other sources of information are also important to balance out the different perspectives in HR practices appraisal. For instance, the same authors noticed that managers mindsets are usually more focused on performance-related outcomes than on other organizational outcomes equally relevant for sustainable careers. This could bias their perception of the HR system in that sense.

Moreover, it is crucial to understand that the way employees experience these practices will have a direct impact on their outcomes (Boon et al., 2011) and the sustainability of their careers (De Vos et al., 2020). As van Beurden et al., (2020, p.2) point out, research has shown that "it is employees perception of HR practices that influences employee behavior", and not the intended policies. Thus, it is important to understand how perceptions of HR practices can change through age. However, it is noteworthy that perceptions of work settings are influenced not only by the environment itself but also by the personal characteristics, needs and values of the perceiver. According to lifespan theory, ageing and adult development affects changes in work motivation in important ways, and that could explain why the utility of certain HR practices depends on age, but also on how employees at different life stages evaluate their work environment (Kanfer & Ackerman, 2004). Thus, these differences in motivation could also bias employees perception of the HR practices offered to them. The consideration of different sources of information (employees and supervisors) regarding the delivery and the experience of HR practices could contribute to better understand the extent to which organizations are implementing maintenance or depreciation models of age management. In fact, recent research and reviews have further explored the significance of employees perceptions on HR practices, centering the attention on the what (the content HR managers intent), how (the context of HR practice, as the same practice can have different outcomes or meanings for employees), and why (the discrepancies among employees that can exist when assessing the same practice) of HR practices (Ostroff & Bowen, 2019; Wang et al., 2020). These attributions and discrepancies can be determined according to the different realities the employees are living, in terms of age, work needs, children, etc. Therefore, it is not just about how employees perceive HR practices, but also how demographic variables, such as age, can play an important role in these attributions.

Differences by Organizational Type

Research on HRM has traditionally been conducted in for-profit organizations. From the seminal work by Huselid (1995), to the most recent research today, scientific journals and researchers have normally focused their attention on this kind of organization. However, this has been criticized by several researchers (Aycan et al., 2000; Carlson et al.2006) who point out the difficulties for generalizing the obtained results (Den Hartog et al., 2004), and emphasize the need to extend this research to other types of organizations.

Differences in how HR practices are delivered to employees from different age groups, have been previously reported at the country level (Peiró et al., 2013), or regarding political systems (Hofäker et al., 2010). Literature regarding other variables has also been found, such as the gender of employees (Powell & Hendricks, 2009); however, from the legal and structural type of organizations, age management has been largely overlooked, as it has normally been addressed from a global perspective (e.g. Heilmann, 2017) and even less in regard to considerations of social enterprises or comparisons in types of organizations.

It is well known that HR policies and practices need to be aligned with organizational culture. As Frenkel and colleagues (2012, p.4205) stated "HR practices not only signify how employees are treated, but they also indicate the broader values of the company and the manner and extent to which they are implemented". Stereotypes about aging as a process of impairment and decrease in productivity (especially after 50-55 years) are widely spread (Blomé et al., 2020). This fact suggests the prevalence of depreciation models of age management in all organization types. However, organizations, depending on their type or legal form can have different tax requirements, different stakeholders, different laws (Cameron & Quinn, 2011), and different cultural backgrounds (Bruton et al., 2010) which will all have an influence on the implemented HR practices. That is, organizations will design their HR policies and practices according to their organizational values and goals, in order to have better internal fit. This has recently been explored by Villajos et al. (2017), who found differences regarding for-profit, public and social factors, on the impact of HR practices on well-being and performance patterns.

Social enterprises have been defined as a hybrid type of organization, where social and economic goals converge. Social enterprises meet the needs of workers thanks to a democratic structure, with more autonomy and participation (Defourny & Nyssens, 2012). As Kalleberg and colleagues (2006) stated, social enterprises would focus its management to more supportive and humanitarian practices, which can give clues as to how they treat employees, taking into account the critical events in life and work each of them experiences. As employees are shareholders as well, they would have more involvement in designing HR practices, and it is plausible that, if they see a need (for example, in training) they can take action and propose different practices. Also, social enterprises will tend to apply profit sharing more equitably, and in a more narrow scope. As the majority of employees are shareholders as well, practices regarding payment, rewards, etc., would be expected to be equally distributed with no age-discrimination.

Moreover, social enterprises are more likely to maintain employees in the long term and, therefore, to reduce labor mobility among employees, keeping job placements for their employees more effectively than for-profit organizations (Eurofound, 2019). In fact, Aiken (2007:5) stated that these organizations "are uniquely placed as mission-driven organizations with a commitment to a specific disadvantaged group", whereas Fonteneau and colleagues (2011) supported the idea that social enterprises encourage the employment of those who are discriminated against in traditional organizations. This has a direct effect on the quality of work, decent working conditions and inclusive management, so it is expected that social enterprises are more likely to be age-friendly.

The mission of public entities is to be at the service of civil society; therefore, their primary objective is not the achievement of economic profits, but rather the welfare of society (Wright & Pandey, 2011), which is more intangible and difficult to measure. Control comes from governments, and some HR practices are dictated by law, such as recruitment, exit or even rewards. In this sense, red tape and bureaucracy might constrain the management of public organizations (Kaufmann et al., 2019). Boyne and colleagues (1999) found that public entities followed a "soft" HRM, naming employment security or life-work balance as one of the most utilized HR practices in these organizations.

The fact that HR practices have to be regulated by law makes them non-discriminatory for any disadvantaged groups. In truth, older employees are one of the targets for active age management in public policies (Cedefop, 2015) encouraging organizations to keep these employees active. Normally, for-profit organizations follow market-driven purposes, and their primary mission is based on the achievement of economic or financial goals, so the maximization of the return on investments becomes especially important. These organizations normally tend to implement HR practices oriented to enhance employees performance. Previous research has found that for-profit organizations use more contingent pay and rewards (Kalleberg et al., 2006), or economic incentives or promotions (Gkorezis & Petridou, 2012), than public ones. Therefore, for-profit organizations will tend to use more "hard", or performance enhancement HR practices, than other types of organizations, such as in public entities (Boyne et al., 1999).

Even though there is evidence of different management practices in social, public, and for-profit organizations, this study will not focus on differences among these organizational types. A more exploratory approach is desired, as the main goal is to analyze the depreciation and maintenance models in HRM. Possible differences in these three types of organizations can guide new research in this area. According to previous reviews that suggest the prevalence of a depreciation model with regard to age management, it is expected that:

Hypothesis 1. Age-related differences will be found in supervisors perception of the implementation of HR practices in all three types of organizations, so that supervisors will report lower levels of implemented HR practices for older workers than for younger and middle-aged employees.

Hypothesis 2. Age-related differences will be found in employees perceptions of HR practices in all three types of organizations, so that older employees will perceive lower levels of HR practices than younger and middle-aged employees.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data was obtained from 1524 employees and their supervisors (159). Regarding employees, 26.6% were younger than 35 years old, 57.2% were between 35 and 50 years old, and 16.2% were 50 years or older. Women represented 54% of the total database, while men 46%. The majority held a bachelors degree (48.1%), while the rest had either a high school degree (21.8%), vocational education (16.2%), or basic education (12.8%). Those with no degree (1,1%) were the least represented. The vast majority were working with an open-ended contract (85%), while the rest had either a temporary contract (12.9%) or were self-employed (2.1%).

Most of the supervisors were between 35 and 50 years old (57.9%), followed by supervisors older than 50 years old (30.8%) and younger than 35 years old (11.3%). The majority were men (64.6%). They held university degrees (75%), high school degrees (11.3%), and to a lesser extent, vocational education (7.5%), basic education (3.1%), others (masters or doctorate, 1.9%) and non-formal education (1.3%). Lastly, the majority were working with an open-ended contract (90.2%), whereas the rest were self-employed (2.5%) or working with temporary contracts (1.3%), the rest had other types of contract (such as for projects, 6.3%).

Instruments

Perceived HR practices. For measuring HR practices as perceived by the employees the 24-items HR practices scale was used, based on the work of Boon and colleagues (2011), and previously adapted and validated into Spanish (Villajos et al., 2019b). The total number of items were distributed into eight HR practices: training and development (α =.81), contingent pay and rewards (α =.83), performance appraisal (α =.93), recruitment and selection (α =.83), competitive salary (α =.86), work-life balance (α =.88), employment security (α =.79), and exit management practices (α =.65). The question presented to the employees was, "my organization offers me..." for each of the HR practices. The response scale was a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). An example of an item is: "...a benefits and rewards plan that is linked to my performance".

Implemented HR practices were measured from supervisors perceptions of implemented HR practices. Specifically, each supervisor had to answer about the practices implemented for individuals in each of the three age groups. An ad-hoc scale was used to measure supervisors ratings of HR practices using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always or always). An item for each HR practice was used. An example of an item is: "How often are training and professional development opportunities offered?".

Age. Employees were required to specify to which age group they belonged: younger than 35 years old, between 35 and 50 years old, and older than 50 years.

Organizational type. Organizational type was assessed using three categories: for-profit organizations (Limited Liability Company and Variable Capital Company), public organizations (local and provincial governments and public schools), and social enterprises (Cooperatives, Work Integration Social Enterprises and Associations).

Data Collection Procedures and Ethical Considerations

Data was obtained from 42 organizations in Spain. In all cases, researchers contacted the company leadership (CEO, HR manager or a similar position), and explained the goals of the project. Employees and their supervisors were asked to participate on a voluntary basis. Confidentiality was assured by the researchers. Procedure was authorized by the ethical committee of the sponsoring university of this study, with the procedure number H1354632059685. Data was gathered on-line, off-line (tablets) and on paper.

Data Analysis Procedures

First of all, descriptive analysis and internal consistencies (Cronbachs alpha) were computed using the IBM-SPSS 26.0 program, this information is available in the previous section. Secondly, Univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted on both samples (employees and supervisors) for each organizational type. Due to the different sample sizes performed the Games Howell post-hoc analyses were used. These analyses serve to identify between which of the three age groups there were significant differences in HR practices.

Results

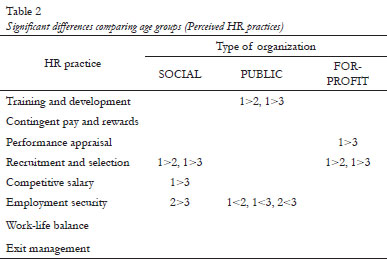

To test for mean differences between age groups in each type of organization, separated ANOVAs were performed with post-hoc Games Howell Test. Results and post-hoc analyses are presented on two different tables. Table 1 presents the results for the significant differences in supervisors report about how these practices are implemented by the organization to employees in each age group. Table 2 presents the results for the significant differences across age groups for the eight HR practices, according to employees perceptions.

Findings show that training and development practices were more frequently offered to younger employees than to middle-aged employees in social enterprises (F(2,190)=15.29; p<.001). Moreover, these practices were found to be more frequently offered to younger and middle-aged employees than to older ones in for-profit organizations (F(2,547)=8.16; p<.001). No significant differences were found in public organizations (F(2,453)=0.83; p=438). Younger employees were offered less contingent pay and reward practices than middle-aged and older employees, and middle-aged employees were also offered fewer of these practices than older employees in public organizations (F(2,453)=8.91; p<.001). However, exactly the opposite was found in for-profit organizations (F(2,496)=25.36; p<.001), as younger and middle-aged employees were offered more contingent pay and reward practices than older employees. No significant difference were found in social enterprises (F(2,453)=0.83; p=438).

Supervisors reported to offer more performance appraisal for younger and middle-aged employees than for older workers in for-profit organizations (F(2,487)=6.85; p=.001), whereas in public (F(2,453)=1.26; p=.284) and social organizations (F(2,190)=7.92; p<.001) no significant differences were found. Regarding recruitment and selection practices, in public organizations (F(2,453)=7.21; p=.001), older and middle-aged employees were offered more practices than younger workers, whereas in for-profit organizations (F(2,496)=3.03; p=.049) middle-aged employees were offered more recruitment and selection practices than younger ones. In social enterprises there were non-significant differences (F(2,190)=2.98; p=.053).

There were mixed results in the case of competitive salaries. Whereas in social enterprises (F(2,190)=4.69; p=.01) these practices were offered more frequently to younger employees than to middle-aged ones; in public entities (F(2,453)=6.11; p=.002) competitive salries were offered to a more frequently to middle-aged and older employees than to younger employees. In for-profits, there were non-significant differences (F(2,496)=2.74; p=.066). Regarding employment security practices, in public (F(2,455)=4.69; p=.01) and for-profit organizations (F(2,496)=18.99; p<.001), supervisors reported less implementation for younger employees than for middle-aged (in public) and less implementation for younger employees than for middle-aged and older workers (in for-profit). Nevertheless, in social enterprises (F(2,190)=21.45; p<.001), no significant differences were registered.

With regard to work-life balance, differences were found only in for-profit organizations. Supervisors reported to offer this practice to a lesser extent to younger employees than to (F(2,496)= 9.72; p<.001) middle-aged and older employees. Non-significant differences were found in social (F(2,190)=1.51; p=.224) and public organizations (F(2,455)=.50; p=.605).

Finally, it was found that older employees were offered more exit management practices than younger employees in public (F(2,451)=6.23; p=.002) and for-profit organizations (F(2,485)=4.75; p=.009). Moreover, middle-aged employees were offered more exit practices than younger employees in public organizations. No significant difference in social enterprises was evident (F(2,190)=2.97; p=.054).

In general terms, younger and middle-aged employees perceived higher levels of some HR practices than older employees in all organizational types, except for employment security, which was perceived more accurately by older (and even middle-aged) employees in public entities. When these results were analyzedpractice by practice, it became evident that in public organizations (F(2,636)=7.78; p<.001), younger employees perceived higher levels of training and development than middle-aged employees. There were no significant differences either for-profit organizations (F=(2,629)1.90; p=.15) or in social enterprises (F(2,242)=3.75; p=.025).

No significant difference among the age groups in any organizational type were found: social (F(2,242)=4.27; p=.015), public organizations (F(2,636)=3.48; p=.031) or for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=.44; p=.642).

Younger employees perceived higher levels of performance appraisal practices than older ones in for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=3.34; p=.036). For social (F(2,242)= 1.48; p= .229) and public organizations (F(2,636)=2.58; p=.077), non-significant differences were noted. For recruitment and selection HR practices, in both social (F(2,242)=6.10; p=.003) and for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=10.18; p<.001), younger employees perceived higher levels than middle-aged and older employees. No significant differences were found for public entities (F(2,636)=.71; p=.491).

Regarding practices of competitive salaries, younger employees perceived higher levels of this practice than older ones in social organizations (F(2,242)=7.55; p=.001). There were non-significant differences for public (F(2,636)=.46; p=.632) and for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=2.34; p=.097).

For employment security practices, middle-aged employees perceived higher levels than older employees in social enterprises (F(2,242)=6.36; p=.002). However, in public organizations (F(2,636)=12.61; p<.001) middle-aged employees perceived higher levels than younger, and older employees perceived higher levels than younger and middle-aged employees. There were non-significant differences in for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=2.06; p=.128).

Finally , for work-life balance no significant age differences were found in any of the three organizational types, social (F(2,242)=2.39; p=.093), public (F(2,636)=.03; p=.968) and for-profit (F(2,629)=2.22; p=.110), nor in the exit management practices: social (F(2,242)=1.32; p=.269), public (F(2,636)=1.06; p=.348) and for-profit organizations (F(2,629)=1.34; p=.264).

Therefore, in general terms, older employees perceived lower levels of some HR practices in all organizational types, except for employment security in public entities, where younger and middle-aged employees perceived less evidence of this HR practice.

In summary, significant differences in the implementation and perception of HR practices between age groups in different types of organizations were found. Supervisors reports of the implemented HR practices yield several differences between age groups in each type of organization. However, the results show limited support for the depreciation model, showing a more complex and diverse situation depending on the type of organization. Indeed, in public entities, different HR practices were considered to be implemented to a higher extent to older employees than to younger and middle age workers: contingent pay and rewards, recruitment and selection, competitive salary, exit management and employment security. No differences between age groups were found for the other practices. More favorable practices for older employees compared with the other groups were also found in for-profit organizations regarding work life balance, employment security and exit management. Practices more oriented toward performance enhancement (training and development, performance appraisal, and contingent pay and rewards) were more favorable for younger and middle-aged workers compared to older employees. In the case of social enterprises, differences in two of the eight organizations considered practices, training and competitive salaries. In both cases, they were more favorable to the younger groups compared with the middle aged group. In general, significantly more differences in comparitive salaries were found than when the perceptions of the workers were taken. Indeed, when considering employees perception, differences were more limited. Younger employees in social enterprises perceived recruitment, selection and competitive salary more favorably, and middle-aged group perceived employment security more favorably than older workers. In for-profit organizations, selection, recruitment and performance appraisal were more favorable to younger employees. In public entities, training and development was better perceived by younger employees, but employment security was better perceived by the older group. All implications for theory and practice will be discussed in the following section.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine if there were significant differences in HR practices offered to employeesin different age groups (less than 35 years old, between 35 and 50 years old, and older than 50 years) in three types of organizations (social, public and for-profit). These groups were analyzed from two distinct points of view: supervisors reports of the implemented HR practices for each age group of employees, and employees perceptions of the HR practices.

Firstly, the results support previous studies suggesting differences in how HR practices are delivered to or experienced by employees in different age groups (Peiró et al., 2013). In both cases, for implemented and perceived practices, significant differences were found in different age groups among organizations. However, employees reported fewer differences in HR practices (12 statistical differences) than their supervisors (24 statistical differences). This suggests that even though organizations implement those practices differently to each age group, it is not perceived strongly by employees. Thus, applying a double type of measurement of HR practices allowed the researchers to confirm the existence of those differences, but at the same time to disentangle what organizations consider they do, in contrast with what employees perceive is done.

Secondly, those differences supported to some extent the depreciation model (Lytle et al., 2015), but showed a more complex picture, and suggest that this model is not equitably distributed in all types of organizations. For the case of social enterprises, a weak support for the depreciation model was found, as supervisors reported lower levels of HR practices for middle-aged employees than for younger ones in two HR practices. However, this contradicts previous research, signaling that social enterprises that allow higher levels of participation of employees will offer more support for employees (Eurofound, 2019; Kalleberg et al., 2006; Villajos et al., 2017), development and maintenance during an entire lifespan. These results should be considered cautiously, because the sample of older workers in social entities was very limited and this may have altered the results.

In the case of public organizations, differences were found in five HR practices as well, but, contrary to the hypothesis given above, were more favorable to older employees, following a more seniority model. This was also reflected to some extent in employees perceptions with regard to employment security practices, which will be discuss below. Although managers in public organizations have reported more red tape restrictions (Kaufmann et al., 2019), some of these practices are dictated by law. The fact that public entities are strictly subjected to those norms and regulations, could affect differences in age with regard to how HR practices are delivered, or it could be that public policies are influencing the design for active management of older employees (Cedefop, 2015), at least in public entities. Moreover, the emphasis in seniority in those entities, with selection and promotion systems based on tenure, could account for differences in selection and recruitment, employment security, contingent pay and rewards and exit management, and/or favoring the group of oldest employees (Berman et al., 2020).

For-profit organizations follow a mixed model, partially supporting hypothesis 1. Some practices were offered more to younger employees (training and development, contingent pay and rewards, and performance appraisal), whereas others were offered more frequently to middle-age and older employees (employment security, work-life balance and exit management). This reflects an age-management model in which performance enhancement practices are mainly provided to employees in the early or middle stages of their careers, and maintenance or support practices are mainly offered to older employees. These results confirm to some extent the depreciation model showing that investments in development are focused on younger or middle-aged workers.This is also supported by the fact that exit management practices were higher for older employees than younger workers, which coincides with the drop in productivity (Blomé et al., 2020). These results support the orientation of for-profit organizations for market-driven purposes, and the implementation of HR practices for the enhancement of employees performance. In those groups, they can expect more return on their investment (Gkorezis & Petridou, 2012; Kalleberg et al., 2006). However, it is important to take into account that research comparing the utility of HR practices for different age groups has found performance enhancement or development practices to be related to increases in performance for older employees (Koiij et al., 2013). Thus, not providing these elements for this group of employees could result in limiting their contribution to the organization.

Thirdly, with regard to employees perceptions, differences revealed that older employees perceived lower levels of HR practices than younger and middle-age workers, showing support for a depreciation model especially in the case of social entities, but also to some extent in private and public entities. Therefore, partial support was found for hypothesis 2.This may be due to the different perceptions that employees have according to their age. Older employees could have a more severe evaluation of their HR practices compared with that of their younger colleagues. For younger employees who are not used to receiving practices, a small amount may seem like a lot to them.

More concretely, in social enterprises, age differences were found for three HR practices, where young (or even middle-aged employees) perceived higher levels than the older ones. This, again, can be due to the fact that the number of older employees in social enterprises was very low compared to the other two groups, although this was taken into account when performing the post-hoc analyses. Also, as normally these employees are an active part of the management decisions (especially when they reach a certain status), older employees expectations may not be met, and so they perceive, comparatively fewer practices. However, in public entities, middle-aged employees perceived higher levels of employment security than younger employees, and older employees perceived higher levels than middle-aged and younger ones, following a seniority model. This corroborates with what was previously found regarding supervisors implemented HR practices, according to the characteristics of civil servants and public policies to keep them at work (Cedefop, 2015). In for-profit organizations, again, younger employees perceived higher amounts of performance appraisal, and recruitment and selection practices than middle-aged or older employees, following this highly competitive environment that dominates these organizations.

In general, some differences were found in the responses between supervisors and employees (Ostroff & Bowen, 2019; Wang et al., 2020). In the case of supervisors and the implementation of HR practices, the differences indicated different models for age management in each type of organization: depreciation, seniority and a mixed model. Thus, the use of different approaches to the measurement of HR practices, implemented and perceived (Boon et al., 2019), allowed the researchers to gain a deeper understanding of HR management in different age groups. These results offer support to the need to use different approaches to the study of HR practices in organizations (Boon et al., 2019) and an employee-centered approach in the study of HR practices (van Beurden et al., 2019) for the sustainability of employees careers (De Vos et al., 2020).

It is also worth noting that the majority of the significant differences were found using the supervisors databases, which indicates that they are aware of these different implementations regarding their employees age, except in social enterprises, where there is more equal or better age management than in public or for-profit organizations. This situation is more balanced in the case of employees perceptions, where there are fewer differences among the three types of organizations.

Some limitations of the present research should be mentioned. A first limitation of the study is the limited sample size of the age group of older employees (more than 50 years). Although the proportion of employees in each age group is representative of the general working population, this limited number precludes the possibility of reaching stronger conclusions, and affects mainly the social enterprises. Thus, taking into account that age groups were distributed unequally, age comparisons in these organizations should be taken with caution. Compensation for this limitation was in using Games Howell post-hoc test for different samples sizes and variances. However, this study opens the research to the study of how different organizational structures and cultures might be promoting or limiting HR practices for workers at all ages.

A second limitation is the way items were formulated for employees and supervisors. While workers were asked about their perceptions of the practices they were offered, supervisors were asked to report on the practices implemented to each age group, possibly making stereotypes more salient about age than the real practices that were being offered to each employee. At the same time, this approach allowed the supervisor to reflect on what type of practices were most commonly offered for employees in each age group.

Future studies could more thoroughly address the study of the differences in how employees and supervisors perceive and implement HR practices, taking into account, for instance, possible differences between life and career stages. Some careers can start later in life, as more and more people delay their insertion into the labor market because they choose to continue their studies for longer periods of time. Practitioners could acknowledge the importance of diversity in organizations and the design and implementation of HR policies and practices that take into account the age of employees, in order to provide sustainability for the workforce aligned with the recommendations of the European Commission. Age management can be understood within the framework of diversity management, which is a fundamental part of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), as it seeks to manage workers fairly, with equal employment opportunities. Future studies could focus more on age management and its relationship with CSR in order to establish closer relationships, and to understand the relationship between the two variables.

In conclusion, by understanding the needs of employees at different stages of their lives, practices can be designed and implemented to be more valuable and effective. Furthermore, variables of context, such as organizational type also play a role on how employees perceive and how supervisors implement HR practices. Differences found by age indicated different models for age management in each type of organization: depreciation, seniority and a mixed model. Academics and practitioners should take into consideration these results to face the challenge of the aging workforce, adopting lifespan perspectives that depend on employees needs and motives for each organizational type.

References

Aiken, M. (2007). What is the role of social enterprise in finding, creating and maintaining employment for disadvantaged groups? Office of Third Sector, Cabinet Office, London, Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk [ Links ]

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., & Kurshid, A. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology, 49(1),192-221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00010 [ Links ]

Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3),309-328, https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115 [ Links ]

Beijer, S. (2014). HR practices at work: Their conceptualization and measurement in HRM research. Gildeprint, The Netherlands [ Links ]

Belin, A., Kuipers, K.D.Y., Oulès, L., Fries-Tersch, E. & Kosma, A. (2016). Analysis report on EU and Member State policies, strategies and programmes on population and workforce ageing. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Retrieved from https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/analysis-report-eu-and-member-states-policies-strategies-and-programmes-population-an-0/view [ Links ]

Bello-Pintado, A. (2015). Bundles of HRM practices and performance: Empirical evidence from a Latin American context. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(3),311-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12067 [ Links ]

Berman, E., Bowman, J., West, J., & Van Wart, M. (2020). Human Resource Management in Public Service. Paradoxes, Processes, and Problems. 6th edition. SAGE, New York, USA [ Links ]

Blomé, M.W., Borell, J., Håkansson, C. & Nilsson, K. (2020) Attitudes toward elderly workers and perceptions of integrated age management practices. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 26(1),112-120, https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1514135 [ Links ]

Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., Boselie, P., & Paauwe, J. (2011). The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person-organisation and person-job fit. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(1),138-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.538978 [ Links ]

Boon, C., Den Hartog, D., & Lepak, D. (2019). A Systematic Review of Human Resource Management Systems and Their Measurement. Journal of Management, 45(6),2498-2537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318818718 [ Links ]

Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2011). Strategy and human resource management. Palgrave Macmillan [ Links ]

Boyne, G., Poole, M., & Jenkins, G. (1999). Human resource management in the public and private sectors: An empirical comparison. Public Administration, 77(2),407-420. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00160 [ Links ]

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3),421-440. https://doi.org/110.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x [ Links ]

Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework (3rd edition.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Carlson, D. S., Upton, N., & Seaman, S. (2006). The impact of human resource practices and compensation design on performance: An analysis of family-owned SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(4),531-543. https://doi.org/110.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00188.x [ Links ]

Cedefop (2015). Increasing the value of age: guidance in employers age management strategies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop research paper, 44. [ Links ]

De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117,103-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.011 [ Links ]

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2012). The EMES approach of social enterprise in a comparative perspective. EMES Working Papers, 12/03,1-47. [ Links ]

Den Hartog, D. N., Boselie, P., & Paauwe, J. (2004). Performance management: A model and research agenda. Applied Psychology, 53(4),556-569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00188.x [ Links ]

DePrins, P., De Vos, A., van Beirendonck, L., & Segers, J. (2015). Sustainable HRM for sustainable careers: Introducing the Respect Openness Continuity (ROC) model. In A. De Vos & B. Van der Heijden (Eds.), Handbook of research on sustainable careers (pp. 319-334). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Eurofound (2019). Cooperatives and social enterprises: Work and employment in selected countries. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg [ Links ]

Eurofound (2020) Sustainable work. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Retreived from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/topic/sustainable-work [ Links ]

Eurostat (2019) Employment rate of older workers, age group 55-64. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tesem050&plugin=1 [ Links ]

Fonteneau. B., et al. (2011). Social and Solidarity Economy: Our common road towards Decent Work. International Labour Organization, Retrieved from www.ilo.org/empent/units/cooperatives/WCMS_166301/lang--en/index.htm. [ Links ]

Frenkel, S., Simon Lloyd D. Restubog & Tim Bednall (2012) How employee perceptions of HR policy and practice influence discretionary work effort and co-worker assistance: evidence from two organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(20),4193-4210, https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.667433 [ Links ]

Gantman, E., Yousfi, H., & Alcadipani, R. (2015). Challenging Anglo-Saxon dominance in management and organizational knowledge. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 55(2),126-129. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020150202 [ Links ]

Gkorezis, P., & Petridou, E. (2012). The effect of extrinsic rewards on public and private sector employees psychological empowerment: A comparative approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(17),3596-3612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.639025 [ Links ]

Hedge, J. W., Borman, W. C., & Lammlein, S. E. (2006). The aging workforce. Realities, myths, and implications for organizations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Heilmann P. (2017) Age Management in Organizations: The Perspective of Middle-Aged Employees. In: I. Aaltio, A. Mills, & J. Mills (Eds.), Ageing, Organisations and Management (pp.141-158). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham [ Links ]

Hofäker,D., Buchholz, S., & Pollnerová , S. (2010 July 5-7). Employment and retirement in a globalizing Europe - reconstructing trends and causes from a life course perspective [paper presentation]. Social Policy Association Conference, University of Lincoln, UK. Retrieved from http://www.social-policy.org.uk/lincoln/Hofaecker.pdf [ Links ]

Huselid, M. A. (1995) The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3),635-672. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1803666 [ Links ]

Ilmarinen J. (2012). Promoting active ageing in the workplace. Publication from European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. European Commission. Retrieved from https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/articles/promoting-active-ageing-in-the-workplace [ Links ]

Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6),1264-1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088 [ Links ]

Kalleberg, A. L., Marsden, P. V., Reynolds, J., i Knoke, D. (2006). Beyond profit? sectoral differences in high-performance work practices. Work and Occupations, 33(3),271-302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888406290049 [ Links ]

Kaufmann, W., Taggart, G. & Bozeman, B. (2019) Administrative Delay, Red Tape, and Organizational Performance. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(3),529-553. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1474770 [ Links ]

Kooij, D. T. A. M., Jansen, P. G. W., Dikkers, J. S. E., & De Lange, A. H. (2010). The influence of age on the associations between HR practices and both affective commitment and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(8),1111e1136. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.666 [ Links ]

Kooij, D. T. A. M., Jansen, P. G.W., Dikkers, J. S. E., & De Lange, A. H. (2014). Managing aging workers: A mixed methods study on bundles of HR practices for aging workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(15),2192e2212. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.872169 [ Links ]

Kooij, D., & Boon, C. (2016). Perceptions of HR practices, person-organization fit, and affective commitment: The moderating role of career stage. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(1),61e75. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12164 [ Links ]

Kooij, D.T.A.M., Guest, D.E., Clinton, M., Knight, T., Jansen, P.G.W. & Dikkers, J.S.E. (2013). How the impact of HR practices on employee well-being and performance changes with age. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(1),18-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12000 [ Links ]

Kordošová, M. (2014) Unfair treatment of older people in the labour market. Eurofound Publications. Retrieved from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/article/2014/unfair-treatment-of-older-people-in-the-labour-market

Liao, H., Toya, K., Lepak, D., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2),371-391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013504 [ Links ]

Liao, H., Toya, K., Lepak, D., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2),371-391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013504 [ Links ]

Liebermann, S., Wegge, J. & Müller, A. (2013). Drivers of the expectation of remaining in the same job until retirement age: A working life span demands-resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(3),347-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.753878 [ Links ]

Lytle, M., Foley, P., & Cotter, E. (2015). Career and retirement theories: Relevance for older workers across cultures. Journal of Career Development, 42, 185-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845314547638 [ Links ]

Naegele, G. & Walker, A. (2006). A guide to good practice in age management. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg. [ Links ]

Neumark, D., Ian Burn, & Patrick Button (2017). Age Discrimination and Hiring of Older Workers. FRBSF Economic Letter, 6, 1-5. Retrieved from https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/el2017-06.pdf [ Links ]

OLoughlin, K., Kendig, H., Hussain, R., & Cannon, L. (2017) Ageism Feature Age discrimination in the workplace: The more things change ... . Australasian Journal on Ageing, 36(2),98-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12429 [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2006). Live longer, work longer. OECD Paris, France [ Links ]

Peiró, J. M., Tordera, N., & Potočnik, K. (2013). Retirement practices in different countries. In M. Wang (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Retirement (pp. 510-542). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Perry, E. L., Dokko, G., & Golom, F. D. (2012). The aging worker and person-environment fit. In J. W. Hedge & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology (pp. 187-212). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195385052.013.0084 [ Links ]

Powell, J. L., & Hendricks, J. (2009). Theorising aging studies. London: Emerald Publishers. [ Links ]

Queiroz, B.L. (2017). Public pensions, economic development, and the labor force participation of older adults in Latin America in 1990-2010. International Journal of Population Studies, 3(1),121-137. https://doi.org/10.18063/ijps.2017.01.008 [ Links ]

Rauch, A., & Hatak, I. (2016). A meta-analysis of different HR-enhancing practices and performance of small and medium sized firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(5),485-504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.05.005 [ Links ]

Schalk, R., Van Engen, M. L., & Kooij, D. (2015). Sustainability in the second half of the career. In A. De Vos & B. Van der Heijden, Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers (pp. 287-303). Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Tordera, N., Peiro, J.M., Ayala, Y., Villajos, E. & Truxillo, D. (2020 online first). HR practices as antecedents of well-being-performance patterns: the moderating role of occupational lifespan stages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120,103-444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103444 [ Links ]

United Nations (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. ST/ESA/SER.A/423. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [ Links ]

Van Beurden, J., Van de Voorde, K. & Van Veldhoven, M. (2020). The employee perspective on HR practices: A systematic literature review, integration and outlook. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1759671 [ Links ]

Van De Voorde, K., & Beijer, S. (2015). The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(1),62-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12062 [ Links ]

Van de Voorde, K., & Boxall, P. (2015). Individual well-being and performance at work in the wider context of strategic HRM. In M. van Veldhoven & R. Peccei (Eds.), Well-being and performance at work: The role of context (pp. 95-111). New York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Veth, K. (2016). The Driving Power of Development HRM and Employee Outcomes Across the Life-Span. Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen, Groningen. [ Links ]

Veth, K. N., Korzilius, H., Van der Heijden, B., Emans, B., & De Lange, A. H. (2019). Understanding the Contribution of HRM Bundles for Employee Outcomes Across the Life-Span. Frontiers in psychology, 10,2518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02518 [ Links ]

Villajos, E., Tordera, N. & Peiró, J.M (2019a). HR practices, eudaimonic well-being, and creative performance: the mediating role of idiosyncratic deals for sustainable HRM. Sustainability, 11(24),6933. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246933 [ Links ]

Villajos, E., Tordera, N., Peiró, J. M & Van Veldhoven, M. (2019b). Refinement and validation of a comprehensive scale for measuring HR practices aimed at performance-enhancement and employee-support. European Management Journal, 37(3),387-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.10.003 [ Links ]

Villajos, E., Tordera, N. & Peiró, J.M. (2017 Novembrer 9-10). HR Practices and sustainable well-being and performance at work. Differences among social, public and for-profit organizations [paper presentation]. 10th Biennial International Conference of the Dutch HRM Network. Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Kim, S., Rafferty, A. & Sanders, K. (2020). Employee perceptions of HR practices: A critical review and future directions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(1),128-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1674360 [ Links ]

Woodrow, C., & Guest, D. (2014). When good HR gets bad results: Exploring the challenge of HR implementation in the case of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(1),38-56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12021 [ Links ]

Wright, B. E., & Pandey, S. K. (2011). Public organizations and mission valence: When does mission matter? Administration & Society, 43(1),22-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399710386303 [ Links ]

Yeatts, D. E., Folts,W. E., & Knapp, J. (2000). Older workers adaptation to a changing workplace: Employment issues for the 21st century. Educational Gerontology, 26,565-582. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270050133900 [ Links ]

Information about corresponding author:

Information about corresponding author:

Esther Villajos

E-mail: esther.villajos@campusviu.es

Submission: 20/06/2020

First Editorial Decision: 31/07/2020

Final version: 06/09/2020

Accepted:18/09/2020

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the Spanish Government with project PSI2015-64862-R (MINECO/FEDER).