Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Perspectivas em análise do comportamento

versão On-line ISSN 2177-3548

Perspectivas vol.2 no.1 São Paulo 2011

ARTICLES

Therapist verbal behavior in the Multidimensional System for Coding Behaviors in Therapeutic Interaction (SiMCCIT)*

Denis ZamignaniI; Sonia Beatriz MeyerII

INúcleo Paradigma

IIPsychology Institute, Universidade de São Paulo

ABSTRACT

Therapeutic interaction has been considered one of the main factors of change in psychotherapy, and its investigation is called process research. Audio and video recording sessions are used to code behaviors which, subsequently, permit the analysis of interaction patterns. The objectives of the study were the presentation of part of a coding system called "Multidimensional System for Categorization of Behaviors in Therapeutic Interaction" and the evaluation of agreement between observers in its use. From a systematic assessment of the literature regarding the classification of vocal verbal behavior, it was found that the existing category systems were not satisfactory for the study of behavior analytic therapy, thus requiring the construction of a new system. A System for Coding Verbal Therapist Behavior was developed containing 16 categories, nine of vocal verbal behavior, three for non vocal verbal behavior and four residual categories. A standardized training for observers was also developed. Its application to one participant produced satisfactory Kappa indexes of agreement ranging from 0.67 to 0.84. The implications of using the system for process research in behavior analytic therapy and in other therapeutic modalities in its different stages are discussed as well as the possibility of using the instrument and its training software for teaching therapeutic skills.

Keywords: research on psychotherapy process, categorization of behaviors, client-therapist interaction, behavior-analytic therapy.

Therapeutic interaction has been an object of study for researchers ranging from various theoretical approaches and fields of knowledge. Process research (Greenberg & Pinsof, 1986; Russel & Trull, 1986) aims at characterizing the interaction (verbal and non-verbal) between therapist and client in order to identify the processes of change which occur within this interaction. According to Luna (1997), the clinic is a favorable environment for the development of research. Within this setting we have access to data from verbal accounts which would rarely be gathered otherwise. In this research environment the researcher is able to keep track of the context in which such behavior occurs; furthermore, a researcher may have access to research participants who provide regular attendance for long periods of time, thus providing repeated observations of the phenomenon of interest.

One of the most frequently employed methods for achieving this goal is the direct observation of audio and\or video recordings of sessions and the classification of this data into the categories of behavior. After the categorization of the observed behavior, a cross-relational analysis amongst these categories is conducted so as to identify the possible effects that different classes of behavior concerning one member of the dyad may have over the other (Russel & Trull, 1986; Wampold, 1986).

Over the past decades, an expressive number of researchers have dedicated themselves to this kind of research (e.g., Almásy, 2004; Baptistussi, 2001; Barbosa, 2001; Barbosa, 2006; Bischoff & Tracey, 1995; Brandão, 2003; Chamberlain & Ray, 1988; Chamberlain, Patterson, Reid, Kanavagh & Forgatch, 1984; Donadone, 2004; Garcia, 2001; Hill, 1986; Hill, Corbett, Kanitz, Rios, Lightsey & Gomez, 1992; Maciel, 2004; Martins, 1999; Meyer & Donadone, 2002; Moreira, 2001; Nardi, 2004; Novaki, 2003; Oliveira, 2002; Silva, 2001; Tourinho, Garcia & Souza, 2003; Vermes, 2000; Yano, 2003; Zamignani & Andery, 2005). At the same time, various topics have been investigated and several methodological resources have been developed for their analysis, providing insightful data into the understanding of the relations that take place within psychotherapy.

Different classification systems were specifically developed in order to analyze the client-therapist interaction (e.g., Baptistussi, 2001; Bischoff & Tracey, 1995; Brandão, 2003; Britto, Oliveira & Sousa, 2003; Chamberlain & Ray, 1988; Chamberlain, Patterson, Reid, Kanavagh & Forgatch, 1984; Donadone, 2004; Garcia, 2001; Hill, 1986; Hill, Corbett, Kanitz, Rios, Lightsey & Gomez, 1992; Margotto, 1998; Martins, 1999; Moreira, 2001; Novaki, 2003; Oliveira, 2002; Tourinho, Garcia, & Souza, 2003; Vermes, 2000; Yano, 2003; Zamignani & Andery, 2005).

Although several of these systems present categories which describe very similar classes of behavior, they resort to different classifications and definitions; thus, there is an incompatibility amongst such classes in virtue of the differences found amongst the elements highlighted by each researcher. Besides, studies in this field usually only investigate vocal verbal behavior. The study of vocal verbal responses in psychotherapy has been conducted since the end of the 1960's and has brought important contributions. However, it is a known fact that an important part of the therapeutic interaction is that of a non-vocal nature (Mahl, 1987).

The development of behavior coding instruments (e.g., Hill, 1986; Rice & Kerr, 1986) involves some steps which must be followed so as to assure their validation and reliability. According to Rice and Kerr (1986), the first step entails the consolidation of a clinical-theoretical foundation which must lay the ground for the development of categories that are aligned with the field of study adopted by the researcher. Building such a foundation is the necessary condition to assure that the developed system presents within its categories the elements (behavior and context of occurrence) that characterize a modality of intervention (this includes both the behavior which must occur and that which must be avoided due to their inconsistency or inadequacy). According to Rice and Kerr, this step would comprise an extensive clinical observation along with an intensive analysis of audio and video recordings; in addition, it would require consulting both the literature and the clinical judgment of the therapists involved.

As per proposed by Rice and Kerr (1986), the second step comprises the specification of the elements through which the behavior included in each class can be recognized. This step would involve a precise description of these behaviors. According to the authors, this requires that efforts be employed so that the instrument is as descriptive and unbiased as possible. It is stated that by being as descriptive as possible, one will not only lessen the complexity of the observations but will also increase the possibilities for using the system in different fields and approaches. According to Rice and Kerr, the tangible outcome from this second stage would be a detailed observers' training manual.

According to Danna and Matos (1999), the definition of an event within a given category must be "(1) objective, clear and accurate; (2) expressed in a direct and affirmative manner; (3) only include elements which are relevant; (4) be explicit and thorough" (p.134). Moreover, the definition must not be "circular"; in other words, the defined term cannot be used in its own definition (Marinotti, 2000). Furthermore, subjective terminology and interpreted or inferred facts should be avoided (Cunha, 1975; Fagundes, 1976/1992). The need for the system to be sensitive enough so that it can answer to all the questions must also be considered; however, such a system should not be excessively detailed as that would result on a dispersion of the results (Wampold, 1986; Zamignani, 2001).

In order to keep coherence and internal validity within the system of categories, some criteria must be followed: (a) the devised categories must be exhaustive1 and mutually excluding; (b) all observed and registered behavior must be classified, regardless of the number of events that are categorized in each class; (c) the categories must cohere with the criteria chosen for the classification as well as with the level of specificity adopted for the classes of events (Danna & Matos, 1999). Rice and Kerr (1986) also suggest that this second stage be closely related to the third, which involves achieving an adequate level of agreement amongst observers, given that the researcher needs to move back and forth between these two steps.

According to Rice and Kerr (1986), the fourth step while devising an instrument concerns the establishment of the system's predictive validity – which comprises the verification of the instrument's sensitivity to patterns of interaction that are related to either the success or failure of the therapeutic intervention. This is a rather complex task and would involve applying the instrument on the investigation of a broad set of therapeutic interactions, so that the data may be related to the results.

According to Rice and Kerr (1986), the last step in developing an observation instrument consists in establishing the construct validity of its categories. Construct validity comprises the evidence which indicates how well the data obtained through an instrument reflects a particular construct2 (Kazdin, 2002). Whenever direct evidence cannot be obtained, circumstantial evidence of the construct is gathered as a means of providing support to the assumption that the measure reflects the construct which is being researched (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955; Suen & Ary, 1989).

An important consideration to be highlighted is that the categorization of events represents (as it should represent) only one step of the research. Such step is accountable for the initial mapping of "generic" processes which occur within the therapeutic interaction. Whenever the categorization of events is not associated to any other type of measure, what it offers at best is a description of the ongoing interaction; however, such a description allows neither the identification of control variables nor the inference of generalizations regarding the phenomenon which is being researched. Due to advances in psychotherapy process research over the past decades we currently have tools which enable the evaluation of the most varied aspects of interaction at our disposal. The association of descriptive categories with other instruments – of outcome measurement (Rice & Kerr, 1986) and session impact (Stiles, 1980), amongst others – may provide much more valuable information regarding the interaction which is being researched.

On a search for elements concerning the study of behavior analytic therapy, Zamignani (2007) carried out a systematic evaluation of the literature concerning the categorization of verbal events in therapeutic interaction. On his research, the author analyzed seven behavior coding systems: (a) Therapy Process Code (Chamberlain & Ray 1988); (b) Therapist Behavior Code (Ford, 1978); (c) Hill Counselor Verbal Response Modes (Hill, 1978); (d) Category System for Coding Interaction in Psychotherapy (Schindler, Hohenberger-Sieber & Hahlweg, 1989); (e) Verbal Response Modes Coding System (Stiles, 1992); (f) Categories concerning the Basic Functions of the Therapists' Verbalizations (Tourinho, Garcia & Souza, 2003) and the (g) Categories for Registering Therapist Behavior (Zamignani, 2001).

The criteria developed by Zamignani (2007) for systematic analyses of instruments are the following: (a) Categories and definitions: this criterion included a clear category definition for each system via either directly observable events or events which required a minimal level of inference. Thus, consistency between the description and the designation of categories is a prominent feature;(b) Overall coherence: This criterion refers to the internal coherence of the system, especially regarding the nature (topographic and/or functional) of the events included in each of the categories as well as the degree of specificity within the different categories;(c) Systematic training: this criterion concerns the existence or non-existence of a manual or systematic training for observers. (d) Previous application on research: this criterion takes into consideration whether the system has been formerly adopted by other researchers or in other studies within the same research group;(e) Compatibility: this criterion evaluates whether the system categories have been developed for the study of behavior analytic therapy and whether its definitions are compatible or adaptable for the study of interaction within this approach.

Zamignani (2007) concluded that none of the analyzed systems satisfactorily met all the proposed criteria. For this reason, the author reexamined the categories and definitions concerning each instrument and behavior catalog which had been previously analyzed; in addition, the author grouped them according to their similarities. A new system of categories was then developed. The analysis and reorganization of the categories of former systems served as a starting point. Moreover, both literature reviews on therapeutic interaction (e.g., Meyer & Vermes, 2001) and therapist training publications (e.g., Fiorini, 1995) were taken into consideration. Furthermore, Zamignani examined the transcripts of behavior analytic therapy sessions that were used in previous studies, thus also considering the view of clinical practitioners and experienced researchers in the field of behavior analytic therapy. This process aimed at identifying variables which had not been addressed in the former systems. The categories were then defined as a means of highlighting the typical types of interactive behavior which constitute behavior analytic therapy.

The Multidimensional System for coding Behaviors in Therapist-Client Interaction (SiMCCIT) is composed by three main coding guidelines. Each one of them represents a dimension or aspect of the participants' behavior; namely: Verbal Behavior, Themes and Motor Responses.

This research stems from the study conducted by Zamignani (2007). It aims at presenting part of the system developed by him - the SiMCCIT - and evaluating the level of agreement between the observers while employing it. This article will focus on the therapists' verbal categories. The complete manual for categorization and systematized training of observers can be found in the work of Zamignani (2007).

Method

Participants

- A client-therapist dyad for the recording of clinical sessions – comprising a male behavior-analytic therapist with 25 years of clinical experience and a 32 year-old female client who is pregnant and distraught over marital problems. The client has not received any previous psychiatric diagnosis.

- Three judges for calculating interobserver agreement. The judges were Psychology undergraduates with clinical training in behavior analysis and at least two years of former experience as behavior analytic therapists; in addition, they have taken part in group research activities under the coordination of an academic tutor (who is responsible for the coauthorship of this article).

Characteristics of the Categorization System

In order to develop a categorization system, categories were adopted based on their grammatical form (e.g., imperative, interrogative, etc.) and their relation to immediately preceding or subsequent events. This choice was based on the literature (e.g., Danna & Matos, 1999; Marinotti, 2000) that recommends that such categorization should be grounded in directly observable behavior. However, the identification of these events takes into account not only their topography, but also the relation to their context of occurrence (a strategy which is also adopted by Hill, 1986.).

A further decision was not to limit the therapeutic interaction study to a verbal-vocal dimension. Thus, the Communicative Gestures categories were added to the verbal behavior categorization system. It was considered that such gestures had close link to verbal vocal communication (Caballo, 1993), as they bear an analogous influence on the verbal vocal responses. In virtue of this choice, it was decided that the data analysis was to be carried out through video recordings as opposed to therapy session transcripts.

The system's record unit is defined as an action (a verbalization segment or non-vocal verbal response) performed by either the therapist or the client. Considering the role played by an action in the immediate context of the session, it would then become classifiable according to the current criteria of one of the categories defined here. A verbalization segment entails a fragment of the participant's speech which accounts for a functional unit - determined by any sort of change in the specific characteristics of one's speech (e.g., class, pause, theme, etc.) - indicated on the definition of each category (though still within the same participant's verbalization). Therefore, the same verbalization may contain more than one segment of speech.

After the first version of a categorization system was developed, a series of trials for the system were conducted, as per described below.

Record of Therapy sessions through the use of a preliminary coding system.

With the aid of the software The Observer3, the first author of this article (indicated here as researcher) applied the preliminary coding system to a therapeutic session which was recorded in video. The categories were reviewed, taking into account the emerging issues and difficulties encountered in this initial categorization.

Once the alterations were made, new sessions were observed and categorized by the researcher and two observers (Observers 1 and 2). These observers participated in the creation process involving the categories and had access to the written material containing the system definitions; however, no formal training for applying the system was carried out.

The method adopted for obtaining agreement between the observers was based on the sequence and duration of the episodes on the comparison between the pairs of observers (always the same researcher and one of the observers). This method, available in the software The Observer, identifies the intersections of time in which both observers applied the same category, regardless of the starting point for the categorized episode.

The calculation employed (at that moment) was the percentage agreement, which is represented by the following formula:

Once the initial agreement between the researcher and each of the observers – as well as the agreement between Observers 1 and 2 – was of less than 40%, the categorization system was reviewed and perfected until the developed categories were considered as being sufficiently broad and precise. Once some sessions were categorized and the system was revised, both a new process of independent categorization and an agreement analysis were carried out (this time only between the researcher and one of the observers – Observer 2). Only one therapy session (Session 11) was repeatedly categorized by both observers and the finetuning of the system occurred successively until a satisfactory index was reached.

On that occasion the Kappa coefficient – suggested by the literature as a more reliable agreement indicator (Suen & Ary, 1989) - was employed. The method for obtaining the index (calculated through the software The Observer) was based on the sequence and duration of the episodes, and resulted on a satisfactory Kappa coefficient of 0.79 (agreement percentage of 0.93), as per illustrated in Table 1. The discordances were reexamined and other adjustments were made on the definitions.

Next, one session that still had not been categorized by both (Session 17) was then categorized independently by the same observers (researcher and Observer 2), who employed the same calculation method mentioned above. Again, there was no formal training for this step. The Kappa coefficient obtained was of 0.67 (agreement percentage of 0.89), which is still considered satisfactory, as per illustrated on Table 2. New adjustments were made based on the disagreements that were obtained, giving rise to a final version of the categorization system.

Final version of the SiMCCIT's verbal behavior categories

After the agreement studies were carried out, a final version of SiMCCIT was proposed and a systematized training for observers was developed. The methodology chosen in order to develop such training was compatible with the behavior analytic proposals for individualized teaching (Holland & Skinner, 1969/1975; Skinner, 1968/1972). A condition of training in which the observer could emit multiple choice answers and be introduced to the categories simultaneously was kept in mind. This training condition corresponds to the notion of active learning, in which an individual's answer to an instruction is followed by immediate consequences (Skinner, 1968/1972). In this format the level of difficulty regarding the presented content rises gradually.

The training contains two packages of sequential activities: 433 activities divided into 15 series for training of categories concerning the therapist and 265 activities divided into nine series for categories concerning the client4. The activities were developed through a software named Clic®5.

The definitions and specifications for each category are presented in subdivided segments throughout the training. Each screen of the training is composed by a segment of a category's definition, as per illustrated by Figure 1.

After reading a segment of definition, the observer must click with the mouse on the instruction screen. This will allow access to an exercise which corresponds to the part of the category which is being instructed. In this exercise, the observer is introduced to a choice between two excerpts of the session transcription and must select the one which corresponds to the definition being presented, as per illustrated on Figure 2. The transcription excerpt used for the comparison with the right excerpt is either clearly different from the category in question or refers to yet another category which has been previously presented during the training sequence.

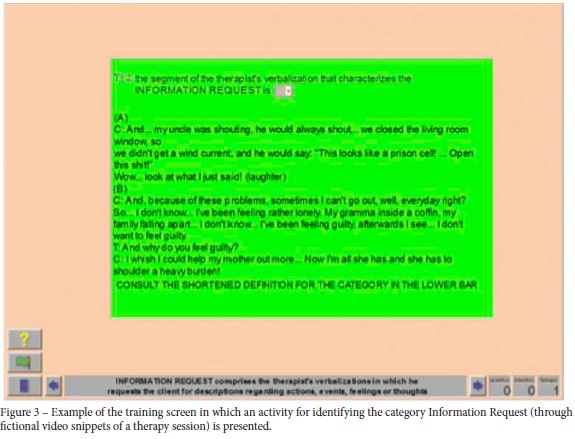

If there is mistake during the exercise, the chosen slot becomes red and the exercise screen remains open. If the answer is correct, the cursor symbol changes indicating a correct answer and the screen automatically shifts to the next instruction segment. At the end of each series (a series comprises the full introduction to a category) the observer is introduced to some additional exercises (for which the answers are more difficult to choose between) through the introduction of fragments of interaction that involve a higher level of similarity between the categories. In addition, the observer is also introduced to some comparison exercises through snippets of sessions recorded in video (these snippets represent fictitious session episodes and were filmed by actors for this sole purpose), as per illustrated on Figure 3.

At the end of the introduction to all the verbal categories and qualifiers, a series of exercises is presented in which the observer must select amongst all of the categories available the one that best represents the excerpt of the transcription or video snippet presented, as per illustrated in Figure 4. The final series of the training presents the instructions and criteria for the insertion of categories on the software The Observer®.

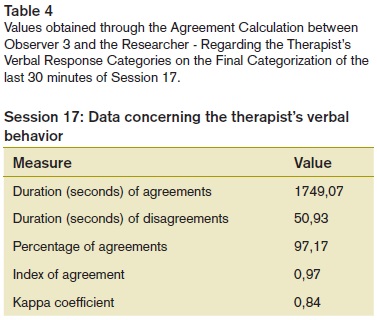

After the development of the observers' training, a new observer (Observer 3 – who had not taken part in the previous process of development and evaluation of the categories) was submitted to it. The training software was installed in a notebook; thus, the observer underwent the training in his own residence. After the standardized training, Observer 3 was guided on how to operate the software The Observer®. At that time, he was not presented with any further instructions regarding the actual categorization system. Observer 3 categorized the therapist's verbal answers through a thirty-minute excerpt of a therapeutic session (Session 17). An agreement calculation was then carried out between this observer's and the researcher's categorization.

The Results section presents the following: the data obtained through preliminary agreement tests (between the researcher and Observers 1 and 2), the final version of the developed instrument, the standardized observers' training and the data pertaining the agreement between the researcher and Observer 3, which was obtained through the training.

Results

The system is composed of 16 exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories, nine which include verbal vocal responses, four which include communicative gestures (motor responses for which the function is analogous to verbal vocal responses) and three which consist of residual categories.

Each category is organized around the following elements: (a) Category Name: a label which describes in few words what is essential to a category; (b) Acronym: two or three letters through which a category can be identified; (c) Shortened name of a category; (d) Definition: a detailed description of the variables – with suggestions of subcategories and examples of excerpts of the related therapeutic interactions - which must control the researcher while he\she identifies the segment of interaction in a given category; (e) General categorization of the category: a synthesis of the elements which constitute a category (with comments to the observer regarding the typical context in which the class verbalizations occur); (f) inclusion or exclusion criteria: criteria through which a category is differentiated from others that describe similar phenomena6. Table 3 presents all 16 system categories.

After the observers training was developed, Observer 3 underwent the training and was guided on how to operate the software The Observer. Next, he categorized the therapist and client verbal responses - along with their respective qualifiers – in 30 minutes of a therapeutic session (Session 17). The agreement data between Observer 3's and the researcher's categorization is available on Table 4.

As per illustrated on Table 4, high indexes of agreement are demonstrated amongst the observers regarding the therapist's categories. As Observer 3 carried out the categorization based only on the observer training (and the occasional consultation to the manual), the training (along with the manual) can be considered as adequately carrying out its role and the categories and definitions can be regarded as sufficiently precise.

Discussion

The choice of furthering the study of the categorization of events, and even of developing a new system stems from the identification of some inconsistencies found on the research literature, both at a national and an international level. These inconsistencies particularly refer to: the vast diversity of categories and definitions employed; the lack of systems that encompass non-vocal behavior and the reduced applicability of part of the systems which have been developed so far for the study of behavior analytic therapy.

Find bellow some features of this therapeutic treatment modality which were considered while developing the system: (a) an emphasis on the consequences of behavior within a therapy session, hence the proposal of differentiating the types of feedback provided by the therapist as a form of Facilitation, Empathy, Approval and Disapproval. (b) the coexistence in literature of the approach of prescriptive-centered therapeutic proposals – included in the categories of Information, Recommendation, Approval and Disapproval- and reflexive-centered therapeutic proposals – included in the system through the categories of Solicitation of Reflection and Interpretation; (c) the importance ascribed to the therapeutic relation when conducting an intervention within the approach – some indicators for the establishment and maintenance of this item are found in the categories of Facilitation, Empathy, Approval, Disapproval as well as in some non-vocal categories.

The construction of the given system of categorization stemmed from an extensive analysis of the literature of different fields, which includes the study of the clinical research carried out thus far and the literature concerning the behavior analytic therapist training; moreover it includes the methodology texts for the development of instruments of observation. In addition to this bibliographical survey, an analysis of the existing categorization systems was developed, with a focus on identifying the relevant elements within the therapeutic interaction.

Furthermore, the construction of the system of categorization was based not only on the systems that had been previously studied, but also through repeated attempts of categorization of the therapy sessions – transcriptions of sessions used in previous studies and video recordings specially made for this research. During the system's development, several consultations were made with groups of researchers who had accompanied and discussed the categorization criteria involved. Considering all of these aspects, it can be affirmed that the first step (i.e., consolidation of a theoretical- clinical foundation) proposed by Rice and Kerr (1986) was accomplished.

Regarding the definitions that were drawn up, each element that forms the categories has been specified with label suggestions for its subcategories (should the researcher be interested), along with several examples for each one of them (it's worth to bear in mind that establishing mutually exclusive subcategories was not part of the proposals found in the work of Zamignani, 2007; thus, no testing following this approach was carried out).As for the descriptive character of the instrument, attention was paid so as to establish categories that required a minimum level of inference. Although the categories proposed are not exclusively of a topographic nature, their definition establishes a series of formal criteria that guide their identification. It can be affirmed that the second step (i.e., the specification of the elements through which the behaviors belonging to each class can be recognized) proposed by Rice and Kerr (1986) has also been accomplished.

An agreement study between observers – concerning the Therapist's Verbal Categories System – was carried out, providing substantially consistent data and a high level of agreement between the different observers. Thus, this criterion was accomplished. However, this data does not disregard the necessity of new agreement studies of other sets of sessions to be carried out. The creation of an extensive systematized training process has proved to be a profitable endeavor, as it has produced a good index of agreements in the therapist's, researcher's and Observer 3's categories – Observer 3 was exclusively exposed to the systematized training. The necessity of new verifications of agreement deserve a mention, particularly the need for a test in which both observers have been trained exclusively through the training software.

Zamignani's work (2007) focused on applying the set of developed categories to different therapeutic sessions. This focus was kept on this research since the initial steps – both on the study of consultation sessions of former research projects and on the development of this research. It is important to add that, although Zamignani's work (2007) has not been the object of study on this article, it accounts for the inclusion of a study of the application of categories to a set of therapeutic sessions which constitutes part of it. Besides, several articles have investigated therapeutic sessions by employing a preliminary or definite version of the systems of categories for the therapist's verbal vocal responses (Amaral, 2010; Araldi & Martins, 2005; Baldivia & Souza, 2005; Barros & Bistocchi, 2006; Carvalho & Henrique, 2005; Donadone, 2009; Kameyama, 2011; Lima & Lopes, 2006; Oshiro, 2011; Pinto, 2007; Rocha, 2008; Rossi, 2011; Rubba & Leite, 2006; Sadi, 2010; Xavier, 2010).

Moreover, other authors have adapted the system categories for the study of different modalities of therapy sessions, such as children behavior analytic therapy (Del Prette, 2006), psychoeducational group therapy (Silveira, 2007) and couple behavior analytic therapy (Marques, 2009). The data gathered through these studies were employed while perfecting the categorization system; what's more, they have pointed out the system's adequacy in the study of different matters concerning clinical research, thus providing some evidence of apparent validity7 for the categories developed throughout this article. However, it is important to consider that more studies are necessary in order to demonstrate its applicability in different intervention modalities, which can eventually lead to its development. A more detailed study of the subcategories would also be necessary so as to provide both a more precise description of each one of them and the development of eventual differentiation criteria amongst them. In addition, the use of subcategories may be necessary in the study of some research matters.

Another piece of evidence of validity in the given instrument underlies its construction process. Similarly to the path traced by Hill (1986), the development of this system of categorization was based on a careful study of other systems, whose categories were later reorganized into a new scheme. According to the author, this process assures a type of content validity. It is adamant to keep in mind that although this evidence is an element which adds consistency, it is not sufficient in order to establish safely the instrument's validity. Thus, evidence from new studies can strengthen this indicator of validity. New studies could follow the recommendation of Rice e Kerr (1986) that the categorization should be associated with the process results.

Greenberg and Pinsof (1986) affirmed on a review article in the field of psychotherapy process research that the lack of a "psychotherapy microtheory" has hindered the development of research on this field. According to the authors, this theory should be sufficiently clear so as to specify what should occur and at which different steps of development this should occur. What's more, this clarification would point out the different relations amongst the various processes that occur at specific points, inside and outside of the therapy session. This microtheory would establish a basis on which the researchers could seek for support when they come across a need for specifying when and where focus on throughout the course of one's therapy. This would allow the identification of patterns of change which occur throughout the therapeutic process.

The SiMCCIT was developed with a focus on the study of the behavior analytic therapy interaction. The sessions in this modality of psychotherapy formed the basis for the system's organization and for the development of its underlying category definitions. A category application exercise was conducted by Zamignani (2007) on the different steps of the behavior analytic process. The developed categories proved to be useful on the description of patterns of interaction that occur at different moments of the therapeutic process. During the initial sessions, the identification of behavior related to the data collection (categories of Information Request, Solicitation of Reflection and Facilitation); the establishment of contract (Information) and the initial feedback (Interpretation and Information) takes place. Behavior concerning the therapeutic relation and the establishment of a therapeutic alliance is identified in the categories of Empathy, Facilitation and Approval, while events which can risk such relation are identified mainly in the categories of Disapproval, but can be identified in other categories, depending on the sequence of events.

The system also predicts the detection of therapist's behavior involved in different intervention styles which may be typical of behavior analytic therapy. Directive interventions can be identified in the categories of Recommendation, Information, Approval and Disapproval, while the categories of Solicitation of Reflection and Interpretation are more typical of reflexive interventions. The non-vocal categories were created bearing in mind the typical actions in the therapeutic process which are not followed by vocal responses (gestures of Approval, Disapproval and Command). The system also relies on residual categories which may be employed on an incomprehensible fragment of a recording (Insufficient Record) or on behaviors which are not included in the other categories (Others Therapist).

The SiMCCIT was applied on this study through the software The Observer, which allows the categorization to take place through the data present on video footage. However, the system has been applied on research using the sessions transcription – on which case the transcription notes regarding the non-vocal categories (e.g., Del Prette, 2006) and the record sheets containing the time intervals (Amaral, 2010) were either suppressed or included. In both cases, employing the system proved to be a feasible endeavor.

Over the past decades, many authors (e.g., Dougher, 1999; Hayes, 1987; Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991; Pérez Álvarez, 1996) have made advances in developing a description of the processes which occur within the behavior analytic based therapy, particularly on the client-therapist interaction within the verbal therapy8. The system herby presented aims at contributing to the advances in this area, allowing a comparison between the data of different research projects. Moreover, a more thorough collection of data may allow the identification of more subtle patterns - which would scarcely be possible through smaller collections of data. Although there is an emphasis on the behavior analytic processes here, it is believed that the phenomena pointed out by the categories that compose the SiMCCIT may also be identified in therapies of different approaches, perhaps with higher or lower emphasis on some of the classes of behavior.

The possibility for employing the SiMCCIT on the therapist's basic abilities training also deserves a mention. Its construction process only had the description of the therapeutic process for research purposes in mind (therefore, it did not aim at developing prescriptive categories, designed for therapist training). However, the very organization of the system of categories points out the events which are relevant for the behavior analytic therapy. This has allowed the use of the software on the training of observers as an auxiliary resource for training behavior analytic therapists.

We believe that SiMCCIT may fill in an important methodological gap in the development of process research in Brazil; Firstly, because of its minute description of the therapist's behavior; Secondly, due to the fact that it was built from a broad survey of behaviors within the therapy session; and thirdly, because it provides the researcher with a broad and user-friendly catalog for the study of different matters regarding the therapeutic process.

References

Almásy, C. (2004). Efeitos da consequência na sessão terapêutica. Dissertação de mestrado. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Amaral, S. S. (2010). Efeitos da solicitação e de subsequente descrição dos relatos verbais de um terapeuta sobre seu desempenho em sessões posteriores (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Araldi, S., & Martins, T. C. (2005). A interação verbal terapeuta-cliente: Categorização e análise da fala de terapeutas formandos e recém formados (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo [ Links ]

Baldivia, F. M., & Souza, M. V. (2005). A avaliação da sessão terapêutica e sua relação com as intervenções do terapeuta (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Baptistussi, M. C. (2001). Comportamentos do terapeuta na sessão que favorecem a redução de efeitos supressivos sobre comportamentos punidos do cliente (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Barbosa, D. R. (2001) Relação entre mudanças de peso e competência social em dois adolescentes obesos durante intervenção clínica comportamental (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Barbosa, J. I. C. (2006). Análise das funções de verbalizações de terapeuta e cliente sobre sentimentos, emoções e estados motivacionais na terapia analítico-comportamental (Tese de doutorado). Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém. [ Links ]

Barros, A. R., & Bistocchi, A. (2006). A fala do cliente em diferentes abordagens: Categorização e análise das relações funcionais (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Bischoff, M. M., & Tracey, T. J. G. (1995). Client resistance as predicted by therapist behavior: A study of sequential dependence. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 487-495. [ Links ]

Brandão, F. S. (2003). O manejo das emoções por terapeutas comportamentais. (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Britto, I. G. S., Oliveira, J. A., & Sousa, L. F. D. (2003). A relação terapêutica evidenciada através do método de observação direta. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 5(2), 139-149. [ Links ]

Caballo, V. E. (1993). Manual de evaluación y entrenamiento de las habilidades sociales. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno de España Editores S.A. [ Links ]

Carvalho, A., & Henrique, C. T. (2005). As intervenções do terapeuta e sua relação com os estados internos relatados pelo cliente e terapeuta (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Chamberlain, P., & Ray, J. (1988). The therapy process code: A multidimensional system for observing therapist interactions in family treatment. Em R. J. Prinz (Ed.), Advances in behavioral assessment of children and families (pp. 189-217). Greenwich: JAI. [ Links ]

Chamberlain, P., Patterson, G., Reid, J., Kanavagh, K., & Forgatch, M. (1984). Observation of client resistance. Behavior Therapy, 15, 144-155. [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletim, 52, 281-302. [ Links ]

Cunha, W. H. A. (1975). Alguns princípios de categorização, descrição e análise do comportamento. Ciência e Cultura, 28(1), 15-24. [ Links ]

Danna, M. F., & Matos, M. A. (1999). Ensinando observação: Uma introdução. São Paulo: Edicon. [ Links ]

Del Prette G. (2006). Terapia analítico-comportamental infantil: Relações entre o brincar e comportamentos da terapeuta e da criança (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Donadone, J. C. (2004). O uso da orientação em intervenções clínicas por terapeutas comportamentais experientes e pouco experientes (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Donadone, J. C. (2009). Análise de contingências de orientações e auto-orientações em intervenções clínicas comportamentais (Tese de doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Dougher, M. J. (1999). Clinical Behavior Analysis. Reno, Nevada: Context Press. [ Links ]

Fagundes, A. J. F. M. (1992). Descrição, definição e registro de comportamento. São Paulo: Edicon. (Trabalho original publicado em 1976) [ Links ]

Fiorini, H. J. (1995). Teorias e Técnicas de Psicoterapia. Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Ford, J. D. (1978). Therapeutic relationship in behavior therapy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(6), 1302- 1314. [ Links ]

Garcia, M. R. (2001). Uma tentativa de identificação de respostas de esquiva e da utilização do procedimento de bloqueio de esquiva através da análise de uma relação terapêutica (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Greenberg, L. S., & Pinsof, W. M. (1986). The psychotherapeutic process: A research book. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Hayes, S. C. (1987). A contextual approach to therapeutic change. In: N. S. Jacobson (Org.), Psychoterapists in clinical practice: Cognitive and behavioral perspectives (pp. 327-387). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Hill, C. E. (1978). The development of a system for classifying counselor responses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 25, 461-468. [ Links ]

Hill, C. E. (1986). An overview of the Hill counselor and client verbal response mode category systems. Em L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Hill, C. E., Corbett, M. M., Kanitz, B., Rios, P., Lightsey, R., & Gomez, M. (1992). Client behavior in counseling and therapy sessions: Development of a pantheoretical measure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39, 539-549. [ Links ]

Holland, J. G., & Skinner, B. F. (1975) A análise do comportamento. São Paulo: EPU. (Trabalho original publicado em 1969). [ Links ]

Kameyama, M. (2011). Efeitos de relatos de sentimentos em supervisão sobre o desempenho em sessão do terapeuta analítico-comportamental (Qualificação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Methodology: General lessons to guide research. Em A. E. Kazdin (Org.), Methodological issues & strategies in clinical research (Vol. 3, pp. 877- 888). Washington: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Kohlenberg & Tsai, (1991). Functional analytic psychotherapy: Creating intense and curative therapeutic relationships. New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Lima, M. N., & Lopes, R. T. (2006). A avaliação da sessão terapêutica em diferentes abordagens: Uma análise da percepção e sentimentos do terapeuta e do cliente (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Luna, S. V. (1997). O terapeuta é um cientista? Em R. A. Banaco (Org.), Sobre comportamento e cognição: Vol. 1. Aspectos teóricos, metodológicos e de formação em análise do comportamento e terapia cognitivista (pp. 299-307). Santo André: ESETec. [ Links ]

Maciel, J. M. (2004). Terapia analítico-comportamental e ansiedade: Análise da interação verbal terapeuta-cliente (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém. [ Links ]

Mahl, G. F. (1987). Exploration in nonverbal and vocal behavior. New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Margotto, A. (1998). Identificando mudanças na interação verbal em situação clínica (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Marinotti, M. (2000). Categorização: Agrupando comportamentos ou eventos em classes. Texto elaborado para uso interno na disciplina "Observação como Fonte de Dados na Análise do Comportamento" do Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Análise do Comportamento da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Marques, E. (2009). Classificação dos comportamentos verbais vocais do terapeuta de casal a partir de um sistema multidimensional de categorização (Monografia de especialização). Núcleo Paradigma de Análise do Comportamento, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Martins, P. (1999). Atuação de terapeutas estagiários com relação a falas sobre eventos privados em sessões de psicoterapia comportamental (Dissertação de mestrado). Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará [ Links ].

Meyer, S. B., & Donadone, J. (2002). O emprego da orientação por terapeutas comportamentais. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 4(2), 79-90. [ Links ]

Meyer, S. B. & Vermes, J. S. (2001). Relação terapêutica. Em: B. Range (Org.), Psicoterapias cognitivo-comportamentais: Um diálogo com a psiquiatria. São Paulo: Artmed. [ Links ]

Moreira, S. B. S. (2001). Descrição de algumas variáveis em um procedimento de supervisão de terapia analítica do comportamento (Dissertação de mestrado).Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Nardi, R. (2004). Proposta de método de interpretação da interação terapeuta-cliente: Análise comportamental da esquiva através do comportamento verbal de terapeuta e cliente em um caso de dor crônica (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Novaki, P. (2003). Influência da experiência e de modelo na descrição de intervenções terapêuticas (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Oliveira, S. C. (2002). A interpretação na terapia comportamental: Um estudo exploratório com uma terapeuta em treinamento (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de Brasília, Brasília. [ Links ]

Oshiro, C. K. B. (2011). Efeitos de intervenções baseadas em análises de contingências extrassessão e na psicoterapia analítica funcional (Qualificação de Doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Pérez-Álvarez, M. P. (1996). La psicoterapia desde el punto de vista conductista. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

Pinto, M. G. A. (2007). Um estudo sobre relações entre o dizer e o fazer: Algumas variáveis que operam no controle do planejamento de sessões terapêuticas. (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Rice, L. N., & Kerr, G. P. (1986). Measures of client and therapist vocal quality. Em L. S. Greenbert & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. V. M (2008). Psicoterapia analítico- -comportamental com adolescentes infratores de alto-risco: Modificação de padrões anti-sociais e diminuição da reincidência criminal (Tese de doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Rossi, P. R. (2011). Categorização de sessões iniciais de psicoterapias bem e mal sucedidas. (Qualificação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Rubba, G. A., & Leite, J. P. (2006). As intervenções do terapeuta em diferentes abordagens: Categorização e análise das relações funcionais (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Russel, R. L., & Trull, T. (1986). Sequential analyses of language variables in psychotherapy process research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(1), 16-21. [ Links ]

Sadi, H. M. (2010). Análise dos comportamentos de terapeuta e cliente em um caso de transtorno de personalidade borderline. (Qualificação de doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Schindler, L., Hohenberger-Sieber, E., & Hahlweg, K. (1989). Observing client-therapist interaction in behavior therapy: Development and first application of an observational system. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28, 213-226. [ Links ]

Silva, A. S. (2001). Investigação dos efeitos do reforçamento na sessão terapêutica sobre os relatos de eventos privados, relatos de relações entre eventos privados e variáveis externas e relatos de relações entre eventos ambientais e respostas abertas (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Silveira, F. F. (2007). Intervenção com cuidadoras em grupo: Descrição da atuação do terapeuta sob uma perspectiva comportamental (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1972). Tecnologia do ensino. São Paulo: Herder. (Trabalho original publicado em 1968). [ Links ]

Stiles, W. B. (1980). Measurement of the impact of psychotherapy sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48, 176-185. [ Links ]

Stiles, W. B. (1992). Describing talk: A taxonomy of verbal response modes. Newbury Pak: Sage. [ Links ]

Suen, H. K., & Ary, D. (1989). Analyzing quantitative behavioral observation data. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Tourinho, E. Z, Garcia, M. G., & Souza, L. M. (2003). Avaliação ampliada de categorias para análise de verbalizações de terapeutas. Projeto de pesquisa. Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém. [ Links ]

Vermes, J. S. (2000). Uma avaliação dos comportamentos do terapeuta durante a sessão: Relatos verbais do terapeuta e do cliente (Relatório final de iniciação científica). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Wampold, B. E. (1986). State of the art in sequential analysis: Comment on Lichtenberg and Heck. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(2), 182-185. [ Links ]

Xavier, R. N. (2010). Microanálise da modelagem de repertórios em um estudo de caso de terapia analítico-comportamental infantil (Qualificação de Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Yano, Y. (2003). Tratamento padronizado e individualizado no transtorno do pânico (Tese de doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Zamignani, D. R. (2001). Uma tentativa de caracterização da prática clínica do analista do comportamento no atendimento de clientes com e sem o diagnóstico de transtorno obsessivo-compulsivo (Dissertação de mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Zamignani, D. R. (2007). O desenvolvimento de um sistema multidimensional para a categorização de comportamentos na interação terapêutica (Tese de doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Zamignani, D. R., & Andery, M. A. P. A. (2005). Interação entre terapeutas comportamentais e clientes diagnosticados com transtorno obsessivo- compulsivo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 21(1), 109-119. [ Links ]

Rua Wanderley, 611.

Submitted: 17/12/2010 *

Partly financed by FAPESP (process # 04/05840-8). Doctoral CAPES Scholarship (March

2004 to February 2005).  Address to correspondence

Address to correspondence

Denis Zamignan

E-mail: denis@nucleoparadigma.com.br and sbmeyer@usp.br

CEP: 05011-001.

São Paulo,

SP.

First editorial decision: 03/03/2011

Accepted for publication: 22/06/2011

1 The term exhaustive refers to the "condition that each and

every relevant behavior is included in one of the categories" (Marinotti, 2000, p. 7) within the system; in other words, the

system must contain as many categories as necessary in order

to include the classes of behaviors of interest, and must

contain a residual category to account for the classes of behavior

which aren't contemplated by the developed categories

(Marinotti, 2000).

2 The term construct refers to the characteristics to be studied

or detected through an instrument, while measures are

means through which these constructs are operationalized

(Kazdin, 2002).

3 This is a computer-based system for behavior analysis

which was developed by Noldus Information Technologies. It

allows categorization to occur directly through the observation

of audio and video recordings.

4 The software used for training observers on this research

is available on a mini DVD attached to Zamignani's (2007)

thesis. Only the training concerning the therapist's categories

will be approached in this article.

5 Clic® 3.0 is a free software. It contains a set of applications

which allows creating various types of multimedia educational

activities. This software was developed by the Department

of Educación de la Generalitat de Cataluña and can be obtained

at http://clic.xtec.cat/

6 In this article, the inclusion and exclusion criteria will not

be presented; what's more, the category definitions are presented

in a shortened version. The full version of the categories

can be found in Zamignani (2007).

7 The term apparent validity has to do with how far the system

of observation seems to measure what it proposes itself

to measure (Suen & Ary, 1989).

8 A large part of the interaction which occurs in psychotherapy

is eminently verbal (Pérez Álvares, 1996) and the investigation of

the therapeutic process must necessarily follow a comprehension

of the verbal processes and their interaction with the non-verbal

events that occur throughout the therapy process.

texto em

texto em