Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Perspectivas em análise do comportamento

On-line version ISSN 2177-3548

Perspectivas vol.8 no.1 São Paulo Jan./June 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.18761/PAC.2016.040

ARTICLES

DOI: 10.18761/PAC.2016.040

Deconstructing psychological therapies as activities in context: What are the goals and what do therapists actually do?

Desconstruindo as diferentes terapias psicológicas como atividades em um contexto: Quais são os objetivos e o que os terapeutas realmente fazem?

Desconstruyendo las terapias psicológicas como actividades en contexto: ¿Cuáles son las metas y qué hacen realmente los terapeutas?

Bernard Guerin

University of South Australia

ABSTRACT

Accounts of 19 psychological therapies were analyzed to extract their goals and activities, collated from first- and second-hand accounts and DVDs. Stripped of the theories and all jargon, the diverse-looking therapy systems converged, and the goals and activities could be analyzed into five functional groups: forming a relationship with someone who is a stranger; solving smaller life conflicts in ways which can be done within a clinical setting; the therapist acting as an audience to train new behaviors; sampling the clients' discourses about their life conflicts; and the therapist acting as an audience to shape these discourses to change the broader life events. These functions were placed in the historical and sociological contexts of therapies arising in the late 1800s, when major life changes began for people in western modernity due to the increases in stranger or contractual social relationships from capitalism and neo-liberalism. For example, much of the therapy process is determined by the (neo-liberal) clinical environment, such as the therapist usually staying within the clinic and engaging clients only for a short time, and dealing with someone who is only in a contractual relationship to the therapist. It was also suggested that these features have probably led to the current emphasis on shaping verbal behaviors (cognitive therapies) through the therapist-as-audience. A comparison to the activities within social work showed that there was a large overlap but social work did more outside the contractual relationships and engaged with the clients' worlds much more.

Keywords: deconstruction, psychological therapy, social work, clinical psychology, psychotherapies, psychiatry, verbal behavior, cognitive therapy, history of psychotherapy

RESUMO

Foram analisadas as descrições de dezenove terapias psicológicas de diferentes abordagens para extrair quais eram os seus objetivos e atividades. As descrições foram coletadas de relatos de primeira e segunda mão e de gravações em vídeo (DVD). Sem as teorias e os jargões as aparentemente diferentes terapias convergem, e os seus objetivos e atividades podem ser analisados dentro destes cinco grupos funcionais: estabelecer uma relação com um estranho; resolver pequenos conflitos da vida de formas que podem ser feitas em um contexto clínico; o terapeuta atuando como audiência para treinar novos comportamentos; pedindo para que os clientes falem sobre os seus problemas; e o terapeuta atuando como audiência para modelar o discursos do paciente para que a mudança atinja um número maior de situações da vida. Essas funções da terapia surgiram no contexto histórico e sociológico do final dos anos 1800, quando grandes mudanças começaram a acontecer na vida das pessoas na modernidade ocidental levando ao aumento de relações entre estranhos ou de relações sociais contratuais dentro do capitalismo e do neoliberalismo. Por exemplo, muito do processo psicoterápico é determinado pelo contexto clínico (neoliberal), como o fato de o terapeuta normalmente ficar na clínica interagindo com os clientes apenas por um curto período de tempo, e atendendo uma pessoa com a qual tem apenas uma relação contratual. Isso também sugere que essas características provavelmente levaram a ênfase atual das psicoterapias na modelação do comportamento verbal (terapias cognitivas) por meio do terapeuta fazendo o papel de audiência. Uma comparação com as atividades do Serviço Social mostrou que existem uma grande sobreposição de tarefas, mas o Serviço Social tem mais ações fora da relação contratual e se envolve muito mais com o mundo dos clientes.

Palavras-chave: desconstrucão, terapia psicológica, serviço social, psicologia clínica, psicoterapias, psiquiatria, comportamento verbal, terapia cognitive e história da psicoterapia

RESUMEN

Se analizaron las descripciones de 19 terapias psicológicas para de ellas extraer sus metas y actividades, recopilando descripciones de primera y segunda mano, y DVDs. Despojados de las teorías y de la jerga, los sistemas de terapia de aspecto diverso convergieron, y las metas y actividades pudieran ser analizados en cinco grupos funcionales: formar una relación con alguien que es un extraño; resolver conflictos de vida más pequeños en formas que se pueden hacer dentro de un ambiente clínico; el terapeuta actuando como audiencia para entrenar nuevos comportamientos; muestreo de los discursos de los clientes acerca de sus conflictos de vida; y el terapeuta actuando como una audiencia para dar forma a estos discursos con el fin de cambiar los eventos de vida más amplios. Estas funciones se situaron en los contextos históricos y sociológicos de las terapias que surgieron a finales del siglo XIX, cuando importantes cambios de vida comenzaron para las personas en la modernidad occidental debido a los aumentos en relaciones sociales contractuales o con extraños dentro del capitalismo y del neoliberalismo. Por ejemplo, gran parte del proceso terapéutico está determinado por el ambiente clínico (neoliberal), como en lo fato de que el terapeuta permanece habitualmente dentro de la clínica interactuando con los clientes sólo por un corto tiempo y trata a ellos como personas que sólo tienen una relación contractual con el terapeuta. También se sugirió que estas características probablemente han llevado al énfasis actual en la formación de comportamientos verbales (terapias cognitivas) por la posición del terapeuta como audiencia. Una comparación con las actividades dentro del trabajo social mostró que había una gran superposición, pero el Asistencia Social hizo más fuera de las relaciones contractuales y se involucró mucho más con los mundos de los clientes..

Palabras clave: Deconstrucción, terapia psicológica, trabajo social, psicología clínica, psicoterapias, psiquiatría, comportamiento verbal, terapia cognitiva, historia de la psicoterapia

Various forms of psychological therapy have been practiced for over a hundred years. The standard history is that in the late 1800s medical practitioners were given new clients to treat who had symptoms which fitted neither known physical diseases nor obvious factors from life conflict and stress. In treating these cases they 'discovered' new 'mental' disorders which they treated initially through talking, suggestions and hypnosis. Emil Kraepelin and others then created a strong focus on arranging the symptoms into categories of disorders with an assumed underlying brain dysfunction (which have never been found, Guerin, 2017). The 'talking cures' continued to develop except for the various behavior therapies which included more actions in the world as well as talking. Recently, more attention has been given to what people think and, following the common assumption that thinking controls other behavior, how to stop or change people's thinking. This has led to cognitive therapies and some of the '3rd Wave' therapies.

Much of this standard history has been challenged, although this paper will not explore the issues (Guerin, 2017). In particular, there have been strong challenges to the assumptions that: the behaviors seen in therapy are symptoms of an underlying physical or mental disorder (Bentall, 2003, 2006); that thinking controls behavior (Guerin, 2016a; Skinner, 1953, 1957, 1985); and that the groupings of symptoms (the DSM in particular) are groupings of internal diseases rather than groupings of external contexts in the person's world (Guerin, 2017). The assumption has also been challenged that the early medical practitioners 'discovered' physical disorders presenting as mental symptoms which had been previously overlooked. Instead, many argue that the 'psychological' or 'mental' disorders were new and arose from the massive changes in the effects of capitalism, bureaucracy, and the replacement of strong family social relationships and obligations by stranger or contractual social relationships with the only obligation being a contract based on monetary exchange (Guerin, 2017; Rose, 1996, 1999; Smail, 2005).

The aim of this paper is not to discuss these assumptions and criticisms but to stand back from any history and look at therapies just as activities which seem to alleviate suffering for many people. Some critics have painted the century or more of therapies as a waste of time or even as dangerous (Masson, 1994), but the starting point here is that there must be much of value but this needs to be seen in context better.

The main questions for this paper, then, were as follows:

if we look at the goals of the various therapies and the actual activities done in therapies, what can we learn about the contexts for therapies being helpful or not, what can we learn about the similarities in between therapies but which are described by different technical jargon and theorizing, and what can we learn about other ways we might help alleviate the suffering of people in such contexts?

Methods

The undertaking was to look at therapies just as social activities in their special context and ask: what are they doing when considered as activities? Presumably they are doing something and hopefully helping people, so what are the goals in contextual terms and what are the activities being done? To carry this out an unusual methodology was used (Bentley, 1935; Guerin, 2005, 2016b; Guerin & Ortolan, 2017): first, to describe some of the common behaviors or activities found in typical western forms of therapies; and second, to look at them as a group and explore how we can functionally group the same effects even though somewhat different approaches are taken and different jargon and theories are used to describe them.

As part of this methodology no claim is being made to have proven that this is how these activities relate to one another, and no claims are being made that all therapies have been included or that all the techniques or activities have been taken into account. The point of the exercise is to help begin to see 'therapy' as just a diverse set of activities which occur in many arenas of life rather than as a unique set of skills invented in the history of western therapeutic encounters. A further point will be to put typical western therapeutic encounters into their historical and social context and highlight:

what forms of suffering are dealt with and which are excluded; which problems are dealt with and which are not; which groups of people might match the social and cultural contexts which are part of the western therapeutic encounter and which peoples of the world will not match these contexts and probably not find such encounters useful of helpful (Guerin, 2017).

To do this, books reviewing the different forms of 19 psychological therapies were used to extract what is reported to be the (1) goals of the therapy, and (2) the activities carried out to achieve these goals. In practice, two standard textbooks were first mined for this purpose, Sharf (2016) and Corsini and Wedding (2010). After this, dozens more psychotherapy textbooks were looked at but what was found was mostly repetition and just a few extra new goals and therapeutic activities were included. To further explore the actual activities within therapy, individual books, written by the therapists themselves where possible, were mined for descriptions and verbatim transcripts of actual therapies in practice. Finally, many DVDs of original therapists performing their therapies were watched for the techniques to be mentioned. In this way the more concrete activities they used could be clarified.

As mentioned above, there was no illusion of being exhaustive for either the number of therapies or the goals and activities they use. Only the 19 main reported therapies were examined closely, and only the main reported goals and activities used for each of those therapies was noted. It should be clear, therefore, that this is not meant to be an exhaustive literature review but a springboard from which other therapies and techniques can be added. Moreover, a point that will be noted below is that there was a lot of overlap in the activities found across the different therapies even when therapies were trying to differentiate (or market) themselves as unique. Also of note, the numerous forms of family therapy were left out of this paper since they would require a more dedicated outline.

One big obstacle to this process was the language and jargon used by the different therapists, usually just repeated in the textbooks with some attempts at clarification. It was at these points of abstract descriptions and jargon that specialist books and DVDs on the individual therapies were consulted. The techniques were then put into a more concrete form not reliant on any theoretical system. Basically, a description was attempted of those activities which actually took place in the therapeutic setting regardless of the language used by the authors to describe such events and their effects.

For the analysis presented here, I grouped the goals and the therapeutic activities in various ways to show some patterns. These are certainly not meant as the only ways this can be done, and the full tables are provided so others can explore their own categorizations. The aim here was an attempt to explore mainly the convergences between stated goals and activities and, more particularly, the functional similarities.

Overall, it must again be repeated that doing this was not intended as some sort of 'proof' of what really takes place in therapy, nor an exhaustive catalogue of goals and techniques. There are too many gaps which preclude this, and I have just listed many of these gaps above. In fact, such a purpose would be futile in any case because therapies constantly change and adapt, and they borrow from each other. There are also many nuances that cannot be captured in the process carried out here, since they cannot be easily 'described' in words (especially when comparing what was theorized to what was seen in the DVDs).

The aim, then, of this methodology was to find a way to describe therapies as concrete activities which take place within limited social contexts— stripped of all the words, marketing and theories spun around them. It was hoped that the ideas stemming from this, while not in any way proof of another better system of therapy, would be useful. In the terms used by many of these same therapies, the purpose was to find a concrete process to 'reframe', 'socially reconstruct' or 're-story' the way therapies are thought about, studied, and practiced.

Results

The goals of therapy: Analysis 1

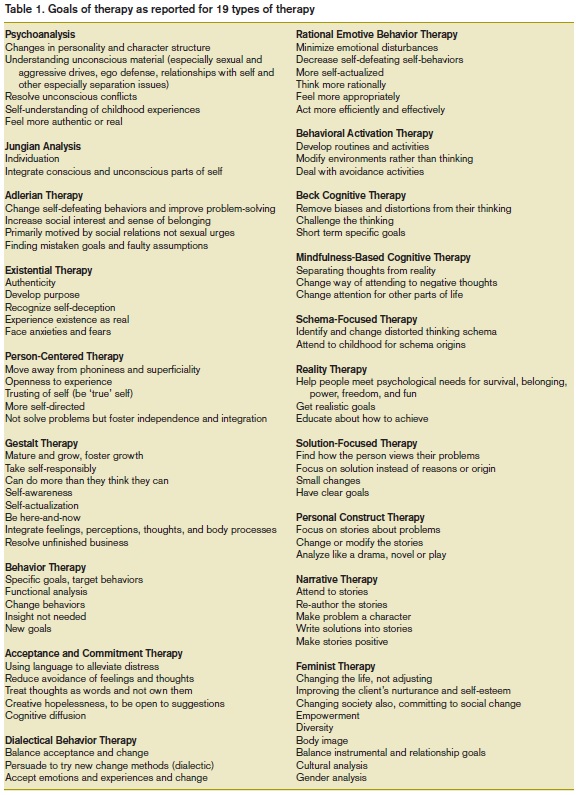

Table 1 presents the goals for each of the major western therapies as reported. Many of the therapies have identical goals which have not been repeated in the table for reasons of space. For example, Jungian Psychoanalysis (Analytical Psychology) has many similar goals to Freudian psychoanalysis which are already listed, so these have not been repeated. The point was to list the main goals rather than be fully exhaustive and repeat almost identical goals under different therapies.

From this raw information shown in Table 1 there appears to be very diverse goals and each therapy appears to be very different, for example: changing personality and character, facilitating authenticity, teaching behavioral skills, changing beliefs and wrong thinking, blocking negative thinking, and developing stories or narratives about oneself.

So on the face of it there seems to be a huge array of goals associated with 'therapy' and what therapists believe should be done to relieve suffering. In at least one way this is concerning since the different goals are linked to specific therapies and it is unclear how well potential clients know the goals of any therapy when they commence. Have the clients adjusted their choice of therapy goals to match their own goals before they walk through the office door, or does the therapist adjust? If the therapist adjusts the goals, it is unclear whether the different goals will be adjusted according to the actions of the client, the types of issues, what the client wants to change, some other factor, or whether the same repetitive procedures are carried out regardless of who walks through the door. In these latter cases, the client might leave the therapy and try another one with different goals.

The goals of therapy: Analysis 2

But despite the apparent plethora of stated goals, it is also clear from Table 1 that there is overlap, and we will find there is even more convergence but it is the jargon or theorizing which makes the goals look more different than they really are. The next analysis therefore, was to try a possible grouping of these goals to see whether patterns might be found if we ignore the jargons used. Following that, the analysis focused on what is actually done in these therapies—what activities are said to be carried out by the therapist.

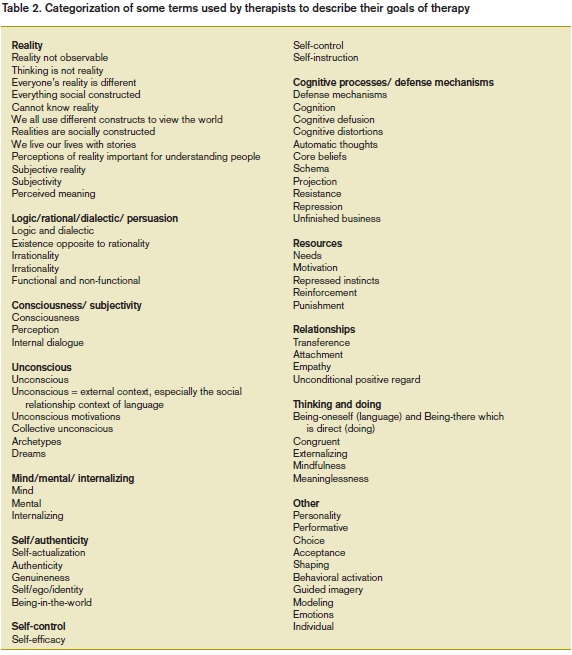

So before grouping the goals of therapy into functional patterns, some of the terms used in the statements of goals needed clarification to get to the concrete activities envisioned by these statements (Guerin, 2016a, 2017). These are presented in Table 2 and discussed below with one possible way to contextualize them into more concrete forms.

For this paper I will discuss some of the terms from a social contextual or behavioral analysis, even though each point will not get full agreement from all readers (Guerin, 2016a). As mentioned, readers are welcome to find other ways to make these terms more concrete and then to try other analyses. Any method of putting what goes on in therapy into context and into more concrete terms beyond jargon will be useful.

Reality: In contextual terms when these goals are put into more observable forms they appear to mean that the person's words are not matching what is happening with their contingent relations (social and non-social) so the goal of therapy is to match their verbal behavior more closely with what is in their world, or to try talking about their world in new ways. As these goals are stated, this could mean trying to prevent verbal constructions of their world, shaping new ways to talk about their world, or giving them skills to gauge their verbal constructions.

Logic/rational/dialectic/ persuasion: These goals seem to be giving the client (persuading them really) ways to talk and act which are more functional in terms of everyday life, or more logical or rational.

Consciousness/ subjectivity: These goals aim to have clients be able to verbalize about their language use or their behavior. Assisting them to become more conscious probably comes close to some forms of mindfulness training, in being able to verbalize or experience more of what is being done or said and the consequences of these.

Unconscious: Making the person's unconscious thoughts or wishes conscious is a goal in many therapies. In concrete terms this usually refers to learning how to name or to talk about those contingences controlling behavior which the person could not previously name or is 'unaware'.

Mind/mental/ internalizing: Many of the therapy goals refer to changing or influencing mental or mind contents which are said to be internal to the person. A contextual description would be that these refer to external contingencies which are difficult to observe or notice, and in particular they are likely to be social or verbal contingencies. Suggestions have been made elsewhere for how to translate many of the specific cognitive or mental descriptions into descriptions based on observable discourse analysis or behavior analysis (Guerin, 2016a, 2017).

Self/authenticity: The goal of building a strong sense of self or authenticity most usually refers to socially shaping stories a person can maintain about themselves and their world which are hopefully beneficial to them. To become authentic might also sometimes refer to aligning what a person says about themselves and what they do, in a similar way to the 'reality' goals given above. The reader can hopefully see how even the disparate-looking existential and narrative therapies converge when framed in this way.

Self-control: This goal probably concerns aligning what is said and what is done in a way to increase the following of 'self-statements'. In a contextual analysis, the 'self ' statements are shaped by external audiences so in concrete terms the therapist probably shapes the client to both say new things about themselves and what they will do, and also to follow those statement descriptions (which will still need audience control but the therapist is assumed to be a strong audience). In terms of later Tables, these might be specific, local changes or else broader life changes and values.

Cognitive processes/ defense mechanisms: These are goals to do with shaping verbal behavior, primarily done by the therapist as the audience. Some are about stopping verbal behaviors (changing cognitive distortions or dysfunctional cognitions; cognitive defusion), and some about changing common verbal behaviors which are used by clients to shape their audiences (defense mechanisms, resistance, and core beliefs converge here). Both the 'cognition' and the 'unconscious defense mechanisms' are, in more observable terms, verbal behaviors shaped by the clients' external and concrete interactions with audiences.

Resources: These are the things or events in life by which the external environment has shaped behavior, and for therapy, particularly by the normal audiences of the client. Some are probably more about the verbal descriptions of possible resources than about engaging with those resources.

Relationships: These goal areas are about shaping social relationships in all their complexity, either with the therapist for therapeutic outcomes (transference, unconditional positive regard) or with other people in the client's life.

Thinking and doing: Like authenticity as a goal, these are goals to (re)shape the person's verbal behavior with respect to their other actions.

The goals of therapy: Analysis 3

With these translations into more concrete activities, we can begin to see more convergence between the diverse therapeutic goals even when the theories or way of talking about goals seem very different. In particular, a lot of the therapeutic goals are about the use of language and how to change or stop certain language patterns, but the different therapies use vastly different systems of theories and jargon to state this. While these are most frequently talked about as 'inner' or 'mental' processes (unconscious thoughts, consciousness, cognitions), we must remember that with a behavior or contextual analysis, they are still verbal behaviors so they are shaped externally by audiences. They do not originate from 'within' a person. This means we can group the diversity in more interesting ways.

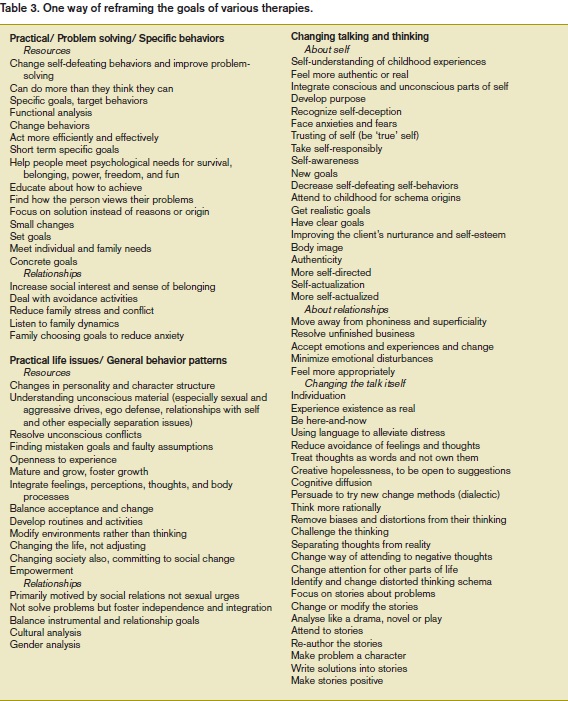

Table 3 shows one possible way to group the many diverse-looking goals of therapy which were presented in Table 1, following the convergences shown in Table 2.

While there are other ways to do this, I have grouped the goals of therapy into three broad categories to capture the essence as viewed through Table 2. These are: therapeutic goals of dealing with a client's practical or specific behaviors which are a problem; changing or shaping new patterns of behavior for the client which are broader than some of the more specific goals stated; and the many ways of changing what a client says or thinks, which is further divided into some sub-categories which are hopefully useful.

Solving specific life problems. Many of the therapy goals can be grouped because they relate to solving practical problems in a client's life which are leading to suffering. As will be seen below when comparing to social workers, psychological therapists have been hesitant about becoming too involved in dealing with mundane life conflicts directly, and have almost exclusively worked within an office by talking about solving the life problems rather than by engaging in the person's life to do this. Most of the direct ways to alleviate suffering have been left to others, such as religious communities, social workers, and community workers, and considered outside the scope of psychologists and psychiatrists. This includes negotiating with other parties, and directly assisting the client with events in their life outside the clinic (not just talking about this in the clinic). To be clear though, this is only in general. Many therapists, whether of a particular school or not, do engage outside the clinic with clients in various ways, and I have known many personally who do this without necessarily telling others since it is frowned upon.

There are two caveats to this, however. First, the history of psychology and psychiatry probably led to this state of affairs, since medical personnel were given clients for whom no obvious external conditions seemed to be bringing on the symptoms (but they were not looking hard enough, Guerin, 2017). So cases for which there were obvious life events causing suffering (poverty, violence) were seen as separate and not part of the professional domain of psychologists and psychiatrists. Standing back and putting the goals and activities of therapies into context in this paper, however, especially when 'internal' events are now seen as external social events, suggests that this separation between disciplines is perhaps no longer tenable. There might be nothing left that distinguishes psychology and psychiatry from other ways of alleviating suffering when mental events and theories disappear. We will see below that many other of the 'distinguishing' features only ever arose from the specific social context which has been part of psychological therapy historically but not necessary.

The second caveat is that when more detailed case studies of therapists are read one often finds that they do, to a limited extent, deal with more practical or obvious external contexts which lead to suffering. These dealings are often not reported in the writings about therapies, however, because of the first caveat—they are left out for professional appearances. As already mentioned, many therapists I know personally do a lot extra things for their clients about mundane practical issues which are causing them to suffer.

To illustrate this further, I will briefly compare the first three big names of psychanalysis on this issue. Alfred Adler spent a lot of time dealing with the very practical issues of his clients that lead to suffering despite writing about generic theories of personality in the style expected of professionals. He had many ways to help people to deal with these issues, including just plain encouragement to achieve their practical goals. Carl Jung was more explicit on this matter although he did not give many details. His position was that his Analytical Psychology was mainly for older people or those not concerned about everyday issues (wealthy or artistic). He believed that for most of the lifespan, the problems leading to suffering were everyday practical issues of resources and relationships, and that these certainly needed addressing. Put roughly, the first half of life was about 'Ego-Self Separation and this involved conflicts around practical life situations. His point was that the main focus of his own special techniques (especially 'individuation') was different to this and usually arose later in a person's life when they were considering bigger questions of life (Jung, 1933).

Sigmund Freud is more difficult to judge on this matter. On the surface, he is presented as very much an in-the-office-only therapist, distanced from his contractual clients behind a couch. However, when more is read about his life and work this picture changes. His clients were mostly wealthy, so in some ways they had less of the practical concerns than the clients seen by Adler, for example, who worked with many poor and elderly people. However, Freud was still involved in his clients' lives to some extent, since many of his clients were relatives of his friends and acquaintances (Billig, 1997; Borch-Jacobsen & Shamdasani, 2012; Freud, 1905/1977; Kramer, 2006). This can be seen as a bad thing—sacrificing professional objectivity—or as a good thing—supporting clients in the life issues which make them suffer in other ways.

Changing more general life issues and problems. Many of the goals of therapy are about making broader changes in the client's life, ranging through personality changes, developing maturity, finding new experiences, broadening social relationships, learning important life skills, and even understanding how gender and power relationships impact and cause suffering. While some of these are couched in 'internal' language, such as making changes to a client's personality, contextually these are really about changing the resource (contingency) structures and social relationships within which a person is embedded. Behavioral Activation Therapy, for example, explicitly states that one of the goals is to modify the person's environments rather than trying to change their thinking, but again, it seems that they attempt to effect change by talking to clients within the clinical setting.

Changing talking and thinking. Finally, a large number of the stated goals of therapy are explicitly about changing what the client says or thinks. It must be remembered that talking and thinking only come about from social contexts so these really imply that the goal is to change the external social relationships with the client's various audiences (Guerin, 2016a; Skinner, 1957). This, we will see later, is most often done in myriad ways by using the therapists themselves as a new audience for the shaping of new talking and thinking to bring about changing the social contexts.

The types of talk and thinking that are goals for changing are hugely diverse, even when similar types from therapies that seem different are put together. For convenience I have listed them into three categories: talking and thinking about self; talking and thinking about social relationships; and changing the talking and thinking itself. Contextually, talking and thinking about self is just a version of talking and thinking about social relationships, because the self is both a product of, and a strategy for dealing with, the social relationships in one's life (Guerin, 2017). However, there are probably many other ways to group and order these goals about talking and thinking. The main point to discover here, though, is that a lot of psychological therapy is taken up with how clients talk and think about their lives and attempts to change this talking and thinking by the therapist acting as a new audience, rather than changing the clients' natural audiences outside the clinic or even engaging these people. [While not included in this paper, family therapies have some very good activities for doing the latter, although they frequently go outside the clinic for this.]

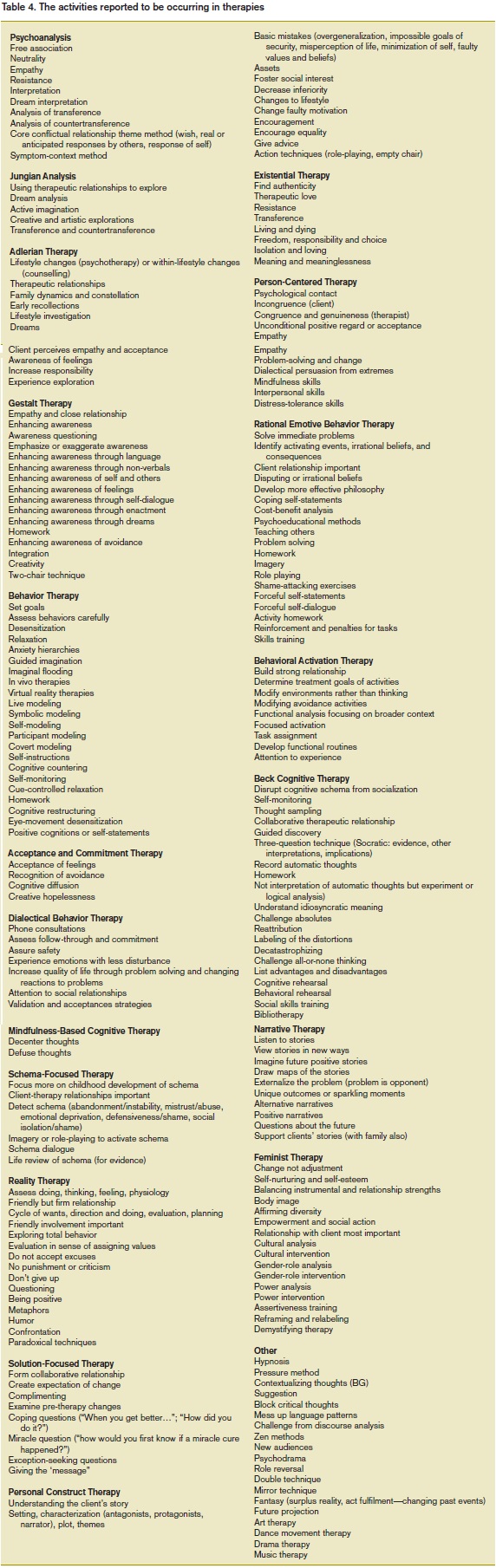

The activities of therapy: Analysis 4

Table 4 presents the main behaviors or activities done by each of the therapies. Once again, they look very diverse but we will find many ways to group them functionally as doing similar things. For reasons of space I have again not put all the repetitions within each therapy. For example, almost all modern therapies include some behavioral homework and some training of skills, but I have only repeated these when different terms are used for these or a different type is used. As another example, ACT helps clarify the clients' values but this converges with many entries earlier in this Table so is not listed separately.

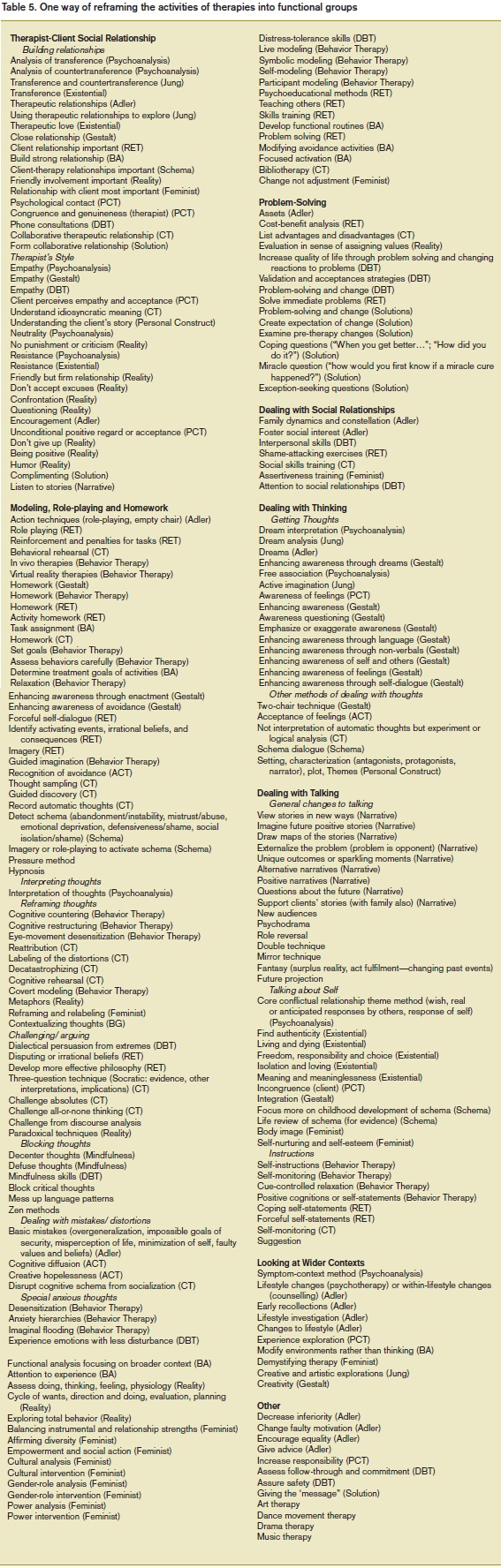

The functions of therapy: Analysis 5

Table 5 shows the activities listed in Table 4 but grouped into some possible similar functions across different therapies. I have made eleven different groupings but some are divided further into subcategories. In terms of the activities listed as important by the different psychological therapies, the main focus would seem to be upon three of these: the social relationship with the client; activities related to changing the client's thinking; and activities related to changing the client's talking. These constitute the bulk of what psychotherapists report they are doing in actual therapy when stripped of the jargon. Even changing very detailed behaviors is done through the talking about the behaviors and their routines in life patterns, with some exceptions.

The social relationship with the client. A lot of activities are directed at forming a relationship with the client in therapy and then acting in ways (the 'style' of the therapy) to further the goals of therapy. Some do this in a friendly style, some more brash, some more challenging (Provocative Therapy, not included here), and some showing openness. However, these need to be placed in the context of therapy more generally for the last one hundred years. One interesting feature of the history of therapy is that it was a system based on working primarily with strangers (in a sociological sense), as modernity brought about the huge rise of stranger or contractual relationships in western societies. Prior to this, discussing issues and problems was usually done with people familiar with or related to the 'client', and therefore usually people with obligations to the clients—a family member, a community priest or religious leader, an elder of the community.

The key point for our analyses about strangers is not whether they are unknown or not, or whether they 'feel' connected somehow to the therapist or not. The key point is that strangers in contractual relationships have no other (familial) ties or obligations which hugely changes the social consequences for these types of interactions (the contingencies). This means that persuasion, influence, follow-ups, attention, etc. have no consequences for the client beyond the contractual relationship. While many therapists and clients do become friends or acquaintances, this is not the norm and is probably more superficial than real—therapists do not normally go to a client's regular family gatherings, for example, or go out to dinner on a regular basis. So what can be achieved within a therapy clinic setting is restricted to general consequences between two strangers and no other people such as family members are involved usually, and there is no obligation of either party to the other once therapy concludes or is interrupted. For example, a family member of the client cannot approach the therapist and demand that they try harder with their cousin or sibling. The main point is that not being able to utilize familial obligations also restricts what can be done to change the clients' audiences outside of the therapy setting.

From this arises at least three more considerations to reframe modern activities of therapy. (1) Some have suggested that the rise of modern 'mental health' issues derives from these new sets of relationships and the anxiety and stress they brought about (Guerin, 2017). So rather than new 'diseases' being found, the therapy situations were the first to deal with people suffering from the (frequently hidden) actions of strangers and the effects of modern capitalism and bureaucracy. (2) It could also be, however, that the breakdown of kin-based communities and extended families in western societies meant that people in distress no longer sought help from the traditional people—family members, priests or religious leaders, or elders, and needed to turn elsewhere. (3) Moreover, it was probably also the case that the family, religious and community leaders who might have been able to influence the 'clients' no longer knew how to deal with the modern issues since the issues were no longer based around family and community consequences but around the plethora of strangers with whom people now had to handle in everyday life.

Whichever of these was true, or all of them, therapists now are in the contexts of modernity: seeing clients whom they do not know; with whom they have no prior relationships; and for whom they no longer have any ongoing obligation or sentiment except what is specified in the contract that is agreed to before engaging in therapy. This both limits and directly shapes what a psychological therapist can change for a client, and the settings in which they can attempt that change.

This gives some historical and cultural context to the large amount of activities found in these Tables directed purely at forming and strategically wielding the social relationship with the client: some are open and seek an 'authentic' relationship (whatever this is in modernity); some like Freud distance themselves from the client and if any attachment is formed this becomes part of the analysis to be solved (transference); while others build a collaborative or problem-solving model which is really based on typical western models of bureaucratic and neoliberal encounters (Braedley & Luxton, 2010; Gouldner, 1954; Graeber, 2015; Hummel, 2014; Lea, 2008; Lipsky, 1980; Merton, 1957; Weber, 1947). Very few therapists go further than this in terms of building some stronger or more lasting relationships and with collateral obligations. Even accepting private phone calls at any time from clients, something done in Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Schema Therapy for example, is considered unusual and undesirable by most therapists. These all look different on the surface but they are all shaped by the historical conditions of therapy in modernity.

What this means, however, is that any sort of change processes which might actually require a stronger or chronic commitment to a person who is suffering, especially in cases where the suffering is arising from the whole social, economic and cultural contexts of the client, are unlikely to be found in modern psychotherapy—they have not developed the techniques and activities to do this because of the original professional orientation or style inherited from the medical originators. The social relationships (and therefore contingencies) available in therapy to effect change are almost exclusively those of strangers in a contractual relationship, and typically a therapist might hear about the family and friends of a client and their conflicts, but they will never actually meet them. Other sorts of more engaged change processes will not even be attempted and this is reflected in the main categories of Table 5. We will see shortly that this lack of any longer terms friendship, commitment or obligation is also reflected in the big emphasis on trying to change thinking and talking as substitutes for doing things with the clients outside the clinic, or as substitutes for training them directly with the people they are engaged with in life.

Dealing with thinking. A very large number of the activities in therapy are focused on finding out the thoughts (cognitions) of clients and attempting to change these. This can be done by challenging or arguing about the thoughts, blocking the thoughts, correcting 'mistakes' in thinking, or reframing or re-attributing the thoughts, and in Table 4 there are many convergences disguised in jargon. From a contextual or behavioral framework, however, there are some special points to note about this.

Contextually, thinking consists of learned language responses in contexts specific or relevant to the audiences or people in relationships with the client. In a stranger-based therapy situation, as described in the preceding section, the therapist acts as a new audience for these articulated thoughts in order to shape new verbal responses which hopefully are more functional and relieve suffering.

There are four potential problems with this, however: (1) shaping new language uses in an office will not guarantee they will engage in other contexts for that client; (2) if there are 'dysfunctional' thoughts or 'mistakes' in thinking, then these have actually been shaped by real audiences and it might be that for the client there are more important social consequences arising from following these 'mistaken' thoughts than from being logically 'correct'; (3) if the 'dysfunctional' thoughts or 'mistakes' have been shaped by real audiences of the client then some consideration needs to be given to what will happen when these thoughts are changed or blocked, since doing so could lead to the client losing those relationships which might be beneficial to them in other ways; (4) and even more important, is that without the therapist having wider contact with the client in their usual contexts, what happens with these three other collateral consequences will remain unknown.

It is not being suggested that re-shaping or reframing thoughts in a clinical setting is a waste of time or should be stopped. Rather, the social effects of these procedures are not usually considered, especially when most theories of therapy assume 'cognition' originates internally and is not social in any case, and can therefore simply be changed by the client changing 'internally'. So the social context of the therapist during 'reframing' needs to be taken into account but this also might require more active involvement by the therapist in the client's social life than currently happens (my earlier point). More engaged methods for finding out about the three earlier points will also be required.

For most clients, who are embedded in modern life and for whom most of their relationships are with strangers, these four issues are perhaps less of a problem. This is not because thinking is not socially shaped, but because there are many alternative relationships which can be formed if the change of language use (shaped by the therapist) interferes in their social life. The compartmentalization property of modern life (Guerin, 2017) also means that there will less impact on any of the particular audiences for the client, since modern life involves many stranger relationships which can change easily and so changing language use does not have to occur across all their audiences. By comparison, the four problems above will be very noticeable for clients who live within strong extended or kin-based communities which have different social properties, and changing or stopping social relationships is a serious matter with wide ramifications. This is perhaps one reason why Indigenous, refugee and other kin-based groups living in modern societies find psychotherapy not as helpful (Guerin, 2017; Ryan, Guerin, Elmi & Guerin, 2017).

Dealing with talking. The re-shaping of talk or language use in therapy is mostly similar to the above considerations of thinking. Rather than single or limited thoughts, however, some therapies work with verbalizing whole stories or narratives produced by their clients. Some of these are about themselves, and some are about facets of their lives. The four potential problems listed above also apply here. For example, if a person has a sociological role within a family or community (Davis & Schmidt, 1977; Gerth & Mills, 1954; Klapp, 1949; Mills, 1963), and the therapist works with the client to shape a new story which should produce fewer conflictual issues and less suffering for that individual, then the impact on the normal audiences in that person's family and community need to be examined carefully. Since there is a public or family role associated with the client's story, changing that story will greatly affect the relationships with community and family. Once again, the therapy in such cases might need to extend beyond contractual obligations and go outside the office to deal with these collateral social effects of changing talking and thinking.

The other common function of changing the client's talk is to shape instructions or directives for the client to follow when not in the therapy situation. These can be presented as self-instructions or rules to follow, but in either case there is once again a backdrop of the social shaping of language with the therapist acting as a new audience.

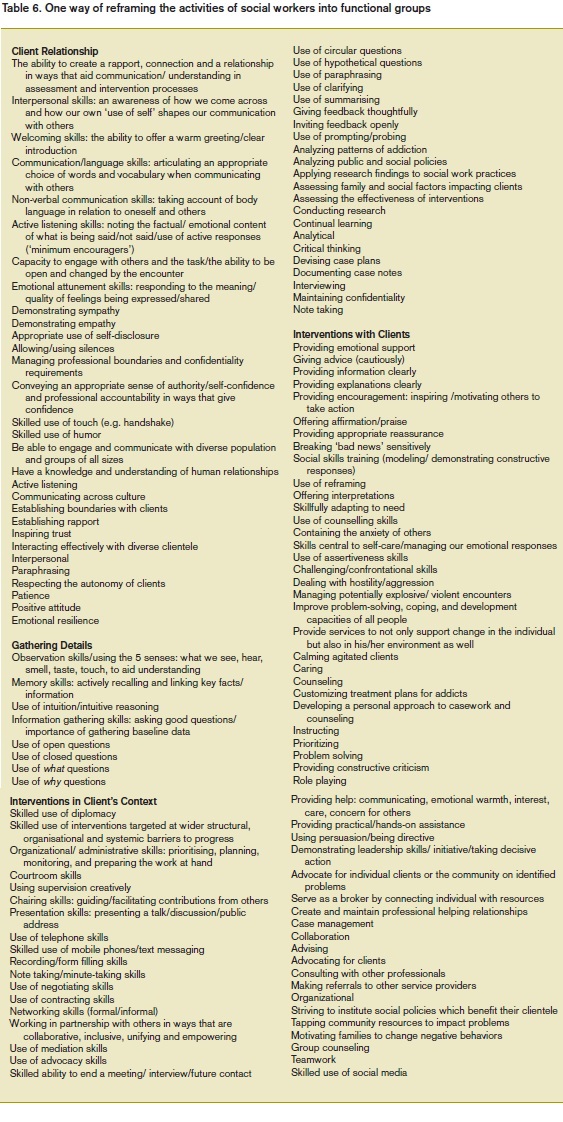

The activities of social work: Analysis 6

A final analysis of interest is to compare Table 5 to a similar list in Table 6 of the activities of social workers. These were garnered from a variety of sources listing the skills and activities used by social workers in practice (e.g., Trevithick, 2012) but not with the same amount of scope and diligence as was done for the therapies. Just a few comparative points will be made.

First, while a similar emphasis is given to forming a brief stranger/contractual relationship with the clients, there are a lot more activities of the social workers relevant to people from different cultural groups, something very absent in Table 4. Second, there are convergences in some of the interventions with clients which are listed to those we have found for the psychological therapies in this paper. Hidden in the jargon of Table 6 there many activities by social workers which attempt to change the thoughts and talking of clients: reframing, giving alternative interpretations (verbal), and other counseling skills. There is also the big range of more localized problem solving interventions as we saw for therapists in Table 5. So the differences between what therapists and social workers do is much less than many people realize. It is not the case that social workers just deal with money and family conflicts and therapists with cognitive processes.

The biggest difference, however, between social workers and psychotherapists is the much greater engagement by social workers in the lives of the clients. This is first reflected in the 'gathering details' listing, in which greater attention is paid to varied contexts such as economic and cultural. The attention to the contexts of the clients' lives is also reflected in the whole section on 'Intervention in client's context' which was noticeably absent in the descriptions of what therapists do, even if I suggested that some might be done without reporting. Social workers have much direct involvement and interventions with people, such as advocacy, negotiation between clients and other people and bureaucracies, and working within the community to assist clients. This presents them with powerful ways to effect change ethically and across the domains of their clients' life worlds.

The bigger point perhaps is that if psychological therapists are not doing anything unique by ways of their activities, and if they are relying on verbal instructions and verbal shaping using themselves as an audience to guarantee that the client walks away from the clinic with new behaviors which will maintain, then perhaps psychotherapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists should be doing a lot more of this direct involvement in a client's life. It not only helps with problem solving but will also provide a better platform for creating changes in thinking and talking which will maintain since the shaping will occur with the real everyday audiences of the client (not the "My therapist said I should not talk like that anymore").

Discussion: The social, historical and cultural context of psychotherapy

The broadest point I wish to share from these brief and explicitly tentative analyses, is that much of what psychotherapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists actually do, and the social contexts in which they do this, was established by the historical situation in the late 1800s arising from the changes to western society moving into modernity. There is no need for these restrictions to remain, and the divide between these and other professionals, especially social workers and community workers, is based on a historic accident.

By some historical accident, the study of the unhappy or disturbed personality has been assigned to physicians, perhaps the least equipped of all investigators of man to deal with the problems. Unlike others in the biological sciences, physicians have next to no training in scientific methodology, and—more important—they are trained to look for causation in the organism rather than the organisation. (Arnold Rose, 1962)

Some psychological therapies, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Schema Therapy, ACT and Feminist Therapies are now seeing the advantages for clients of broadening the scope and engagement of the therapy, but the main gains of doing this will be noticed when working with clients from kin-based communities and extended families, who at present do not relate well to western forms of therapy. In modernity the number of such groups has been reduced because the dynamics of both capitalism and neo-liberal policies favor small families (Guerin, 2016a), but there are many Indigenous, immigrant, and refugee communities living in western societies which are run along these lines. They are the ones least satisfied with western therapies and the analyses in this paper perhaps begins to show us why (Guerin, 2017, Chapter 8; Ryan, Guerin, Elmi & Guerin, 2017). The extended families shape so much of the client's behavior of doing, talking and thinking, that sitting in an office for an hour with a stranger who attempts to act as an important and strong audience in order to socially re-shape talking and thinking, will just not work except in the short-term perhaps. One way I have framed this is that people in kin-based communities always have at least two consequences for any behavior—directly for the environment or the person they are behaving towards, and then also from the community or family.

In my fieldwork with a refugee community over many years, people actually told me this directly— their disbelief that talking to a stranger in an office would solve any of their 'mental health' problems. Also as mentioned earlier, their beliefs, attributions and 'mistaken' thinking have already been shaped by their close community and family so changing this in therapy can have all sorts of negative ramifications. Changing talking and thinking (such as cognitive therapy) does not have to be avoided, it just needs to be done by closer engagement and consultation with people in those communities and families for whom the client's current talk, which seems dysfunctional to the therapist, is likely to be functional in some way.

Another point highlighted in these analyses is the extent to which therapies with different jargons, and which often attempt to prove that they are distinct, in reality converge in what their activities are functionally attempting to do, and they also converge with social work.

In summary, the main thrusts of almost all the western therapies for goals and activities are to:

- form a working relationship with a client in a stranger/ contractual relationship

- solve smaller or more localized conflicts in the client's life which are amenable within an office

- act as a new audience to train new behaviors and skills where appropriate

- find out their talk and thinking around the problems and suffering they have

- attempt to act as a new audience to change those thoughts and talking in ways that should be beneficial and reduce the suffering, especially for broader life conflicts

Different therapies focus more or less on different aspects of this, but they all cover much the same ground, or else specialize in only certain types of problems and suffering.

A final idea from these analyses is that while the modern fracturing of social relationships into mostly stranger or contractual relationships (in terms of frequency) has led to a compartmentalization of the bits of our lives (Guerin, 2016a), this is probably why current therapies do work well a lot of the time. For most people in modernity, being shaped by a stranger to do new behaviors is now a common occurrence (such as starting a new job; starting at university or school), so the therapist-asnew- audience is not completely unusual except for those living in kin-based communities or extended families (e.g., Guerin, & Guerin, 2008). But this also means that changes made within therapy can be lost just as easily, since there is less continuity between what people say and think about themselves and their life problems when moving between the many stranger-based audiences we now have in modern life (Guerin, 2017). This is probably also why there is a therapeutic emphasis on more general thought patterns (especially talking about 'self ' and identity), stories, and narratives, since these can all hopefully guide the clients over the different audiences in their lives even when the therapist is no longer present to be their new audience.

In all, while none of these Tables prove a new version of therapy, it is hoped that the overall societal strategy of conducting western forms of therapy can now be viewed in a novel way, having stood back and looked at a bigger picture of what the goals of therapy are said to be, and the activities which were found. I envisage the convergence of all these therapeutic activities, including those from social work, to form a new approach for relieving suffering, including those forms we currently label as 'mental' (Guerin, 2017). This approach would be devoid of jargon and marketing differentiation, and focus on observing and changing the many complex and nuanced life contexts from which the suffering arises, rather than on trying to uniquely describe the activities which are engaged. After all, those therapist activities which lead to change must also be shaped by what works in the clients' worlds, so focusing on learning the clients' contexts, economic, social, historical, and cultural, is of double importance.

We might then see a new 'post-internal' form of relieving people's suffering, which does not differentiate between mental and non-mental health, and which uses common methods for changing the clients' external contexts whether this is for verbal or other behaviors (since verbal is social). This would not distinguish between psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists, and other professionals, but instead distinguish between those who might specialize in common problematic contexts of modern life, common forms of social relationship conflicts, common forms of conflict and suffering in Indigenous communities, or other specializations dictated by external concerns giving rise to clients' suffering, rather than theoretical metaphors about 'inner' turmoil.

References

Bentall R. P. (2003). Madness explained: Psychosis and human nature. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Bentall, R. P. (2006). Madness explained: Why we must reject the Kraepelinian paradigm and replace it with a 'complaint-orientated' approach to understanding mental illness. Medical Hypotheses, 66, 220–233. [ Links ]

Bentley, A. F. (1935). Behavior knowledge fact. Bloomington, Indiana: Principia Press. [ Links ] Billig, M. (1997). Freud and Dora: Repressing an oppressed identity. Theory, Culture and Society, 14, 29–55. [ Links ]

Borch-Jacobsen, M. & Shamdasani, S. (2012). The Freud files: An inquiry into the history of psychoanalysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Braedley, S., & Luxton, M. (2010). Neoliberalism and everyday life. Montreal, Canada: McGill- Queen's University Press. [ Links ]

Corsini, R. J., & Wedding, D. (2010). Current psychotherapies (9th Ed). NY: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Davis, M. S., & Schmidt, C. J. (1977). The obnoxious and the nice. Sociometry, 40, 201-213. [ Links ]

Freud, S. (1905/1977). Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria ('Dora'). (Penguin Freud Library Volume 8) London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Gerth, H., & Mills, C. W. (1954). Character and social structure: The psychology of social institutions. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Gouldner, A. W. (1954). Patterns of industrial bureaucracy. NY: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Graeber, D. (2015). The utopia of rules: On technology, stupidity, and the secret joys of bureaucracy. London: Melville House. [ Links ]

Guerin, B. (2005). Combating everyday racial discrimination without assuming racists or racism: New intervention ideas from a contextual analysis. Behavior and Social Issues, 14, 46-69. [ Links ]

Guerin, B. (2016a). How to rethink human behavior: A practical guide to social contextual analysis. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Guerin, B. (2016b). Arthur F. Bentley's early writings: His relevance to behavior analysis, contemporary psychology and the social sciences. Perspectivas em Análise do Comportamento, 7, 1-35. [ Links ]

Guerin, B. (2017). How to rethink mental illness: The human contexts behind the labels. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Guerin, B., & Guerin, P. B. (2008). Relationships in remote communities: Implications for living in remote Australia. The Australian Community Psychologist, 20, 74-86. [ Links ]

Guerin, B., & Ortolan, M. O. (2017). Analyzing domestic violence behaviors in their contexts: Violence as a continuation of social strategies by other means. Behavior and Social Issues, 26, 5-26. [ Links ]

Hummel, R. P. (2014). The bureaucratic experience: The post-modern challenge. London: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern man in search of a soul. London: Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Klapp, O. E. (1949). The fool as a social type. American Journal of Sociology, 55, 157-162. [ Links ]

Kramer, P. D. (2006). Freud: Inventor of the modern mind. NY: Atlas Books. [ Links ]

Lea, T. (2008). Bureaucrats & bleeding hearts: Indigenous health in northern Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. [ Links ]

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Masson, J. M. (1994). Against therapy. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press. [ Links ]

Merton, R. K. (1957). Social theory and social structure. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Mills, C. W. (1963). The competitive personality. In Power, politics and people: The collected essays of C. Wright Mills. NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rose, A. M. (1962). A social-psychological theory of neurosis. In A. M. Rose (Ed.), Human behavior and social processes: An interactionist approach (pp. 537-549). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Rose, N. (1996). Inventing our selves: Psychology power, and personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Rose, N. (1999). Governing the soul: The shaping of the private self (2nd Ed.). London: Free Association Books. [ Links ]

Ryan, J., Guerin, P. B., Elmi, F. H., & Guerin, B. (2017). Going 'Walli' and having 'Jinni': Somali refugee women contextualize their mental health. Unpublished paper: Penn State University, Brandywine. [ Links ]

Sharf, R. S. (2016). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling: Concepts and cases (6th Ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Skinner, B. F. (1985). Cognitive science and behaviourism. British Journal of Psychology, 76, 290- 301. [ Links ]

Smail, D. (2005). Power, interest and psychology: Elements of a Social Materialist understanding of distress. London: PCCS Books. [ Links ]

Trevithick, P. (2012) Social work skills & knowledge: A practice handbook (3rd Ed.). London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

Bernard Guerin

University of South Australia

St Bernard Road, South Australia 5072

E-mail: bernard.guerin@unisa.edu.au

Submetido em: 25/10/2016

Primeira decisão editorial: 22/02/2017

Aceito em: 05/04/2017