INTRODUCTION

The new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 and demonstrated high severity and great power to spread across continents, overcoming social and economic problems, becoming a global health disaster1 . The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 20202 and it was recognized in Brazil through Ordinance No. 454/2020 of March 20203,4 .

Sanitary measures were already being established and the Chamber of Deputies approved Decree No. 6/2020, which recognizes the state of public calamity in the country, reflecting the expansion of expenses to face the pandemic5 . Given this scenario, the Unified Health System (SUS) assisted as a health service for about 200 million inhabitants, however with its large territorial extension and different sociodemographic and geographic characteristics, the epidemiological behavior of the virus was strongly influenced by unequal access to health services6 .

In Brazil, the southeast region was the most affected with 14,996,985 cases and 338,854 confirmed deaths 7 and the state of Rio de Janeiro stood out in the region for having the highest mortality rate in Brazil with 447.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants . In addition, it was widely affected by the virus due to socioeconomic issues, such as type of housing, access to basic sanitation, means of transport and, mainly, the population contingent7-9.

Even with the declaration of the end of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern regarding COVID-19 on May 5, 2023, this is still a topic that has been studied and discussed in the most varied contexts and associations, and knowing the profile of the mortality and lethality due to COVID-19 should be priorities, considering that the disease evolves unfavorably in vulnerable and infected patients. In view of the above, the present study aims to analyze temporal variations in the incidence, lethality and mortality rates due to COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro during the period from January 2020 to December 2022.

METHODS

Study Design

This is an ecological study of population-based time series of public access available on the website of the Secretary of Health of the State of Rio de Janeiro. This study is part of an umbrella project in which each state in Brazil was analyzed separately, following a standard protocol10.

Study Place and Period

Research carried out from January 2020 to December 2022 in the conglomerates of the 92 municipalities that make up the state of Rio de Janeiro, one of the Federation Units located in the Southeast Region of Brazil.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

The population of the state of Rio de Janeiro was used and all confirmed cases and deaths related to COVID-19 using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10), of “B34.2, Coronavirus infection of unspecified location” and “U07.1 COVID-19, identified virus” or “U07.2 COVID-19, unidentified virus”, considering clinical and/or epidemiological criteria of the disease.

Data collect

Confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths were extracted from the Rio de Janeiro Health Secretariat 11 on February 8, 2023. Data on the population of the state of Rio de Janeiro were extracted from the Brazilian population projection base of the Units of the Federation by sex and year for the period 2000-2030 from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) available in the database of the Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (DATASUS), and for the years between 2020 and 2022 16,946,541, 17,014,734 and 17,078,778 inhabitants were considered, consecutively12.

Data Analysis

The study variables were organized into independent (time) and dependent (confirmed cases, confirmed deaths, lethality rate, mortality rate and incidence rate). The incidence, mortality, and gross lethality rates were calculated using the direct method, with incidence and mortality expressed per 100,000 inhabitants, and lethality expressed as a percentage.

For trend analysis, the methods proposed by Antunes and Cardoso 13 were used . Time series construction rates were calculated using the statistical technique of generalized linear regression by the Prais-Winsten method, which allowed first order autocorrelation corrections in the analysis of the values of the organized time series.

Thus, the following values were estimated: angular coefficient (β) and its respective probability (p), considering a significance level of 95% (CI95%) and the percentage variation of daily change (Daily Percent Change – DPC) . This procedure made it possible to determine the rates as increasing, decreasing or stationary and to quantify the percentage variation in the daily rates of incidence, mortality and lethality. Data tabulation and calculation of raw rates were performed using the Microsoft Excel 2019 application and estimates of annual percentage change rates were performed using the statistical software STATA MP 17.014.

Ethical and Legal Aspects of Research

This research used data from the public domain and open access, available in the Health Information base of the Health Department of Rio de Janeiro, without needing to be assessed by the National Research Ethics Committee (CONEP) and analysis of the Research Ethics Committee system (ZIP CODE).

RESULTS

In the state of Rio de Janeiro, the Health Department notified, from January 2020 to December 2022, 2,457,510 cases and 76,368 confirmed deaths of COVID-19. Table 1 details the distribution of the number and proportion of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths by month and year in the state of Rio de Janeiro, from 2020 to 2022. The first cases occurred in January (0.08%) and February (0.02%) of 2020. The highest frequencies were concentrated in November of 2020 (17.00%) and December of 2020 (21.24%). In 2021, March (15.72%) and in January 2022 (56.51%). As for deaths, March 2020 (0.39%) obtained the first records, the peak being in May 2020 (23.92%), followed by April 2021 (19.64%), January 2022 (28.20 %) and February 2022 (28.62%).

Table 1 : Distribution of the number and proportion of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths by month and year in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, 2020 – 2022.

| Year | Month | Confirmed cases | confirmed deaths | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| 2020 | January | 489 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.00 |

| February | 108 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| March | 8,639 | 1.36 | 122 | 0.39 | |

| April | 53,947 | 8.48 | 3,487 | 11.2 | |

| May | 64,261 | 10.10 | 7,449 | 23.92 | |

| June | 57,613 | 9.05 | 3,596 | 11.55 | |

| July | 60,017 | 9.43 | 2,388 | 7.67 | |

| August | 51,629 | 8.11 | 2,182 | 7.01 | |

| September | 47,958 | 7.53 | 2,193 | 7.04 | |

| October | 48,425 | 7.61 | 1,899 | 6.10 | |

| November | 108,224 | 17.00 | 2,537 | 8.15 | |

| December | 135,193 | 21.24 | 5,289 | 16.98 | |

| Total | 636,503 | 100.00 | 31,142 | 100.00 | |

| 2021 | January | 90,287 | 11.33 | 4,259 | 10.89 |

| February | 50,053 | 6.28 | 2,346 | 6.00 | |

| March | 125,206 | 15.72 | 5,101 | 13.04 | |

| April | 104,007 | 13.06 | 7,682 | 19.64 | |

| May | 106,556 | 13.38 | 5,724 | 14.64 | |

| June | 69,297 | 8.70 | 3,575 | 9.14 | |

| July | 73,292 | 9.20 | 2,521 | 6.45 | |

| August | 100,354 | 12.6 | 3,306 | 8.45 | |

| September | 39,160 | 4.92 | 2,833 | 7.24 | |

| October | 12,676 | 1.59 | 1,157 | 2.96 | |

| November | 8,802 | 1.11 | 388 | 0.99 | |

| December | 16,853 | 2.12 | 216 | 0.55 | |

| Total | 796,543 | 100.00 | 39,108 | 100.00 | |

| 2022 | January | 578,975 | 56.51 | 1,725 | 28.20 |

| February | 37,998 | 3.71 | 1,751 | 28.62 | |

| March | 5,087 | 0.50 | 345 | 5.64 | |

| April | 4,731 | 0.46 | 102 | 1.67 | |

| May | 44,241 | 4.32 | 91 | 1.49 | |

| June | 155,421 | 15.17 | 596 | 9.74 | |

| July | 39,782 | 3.88 | 587 | 9.59 | |

| August | 4,964 | 0.48 | 182 | 2.97 | |

| September | 2,237 | 0.22 | 60 | 0.98 | |

| October | 7,345 | 0.72 | 51 | 0.83 | |

| November | 117,718 | 11.49 | 332 | 5.43 | |

| December | 25,965 | 2.53 | 296 | 4.84 | |

| Total | 1,024,464 | 100.00 | 6,118 | 100.00 | |

| Grand total | 2,457,510 | 76,368 | |||

Source: Confirmed cases and deaths extracted from SES/RJ on February 8, 2023, available at: http://sistemas.saude.rj.gov.br/tabnetbd/dhx.exe?covid19/esus_sivep.def

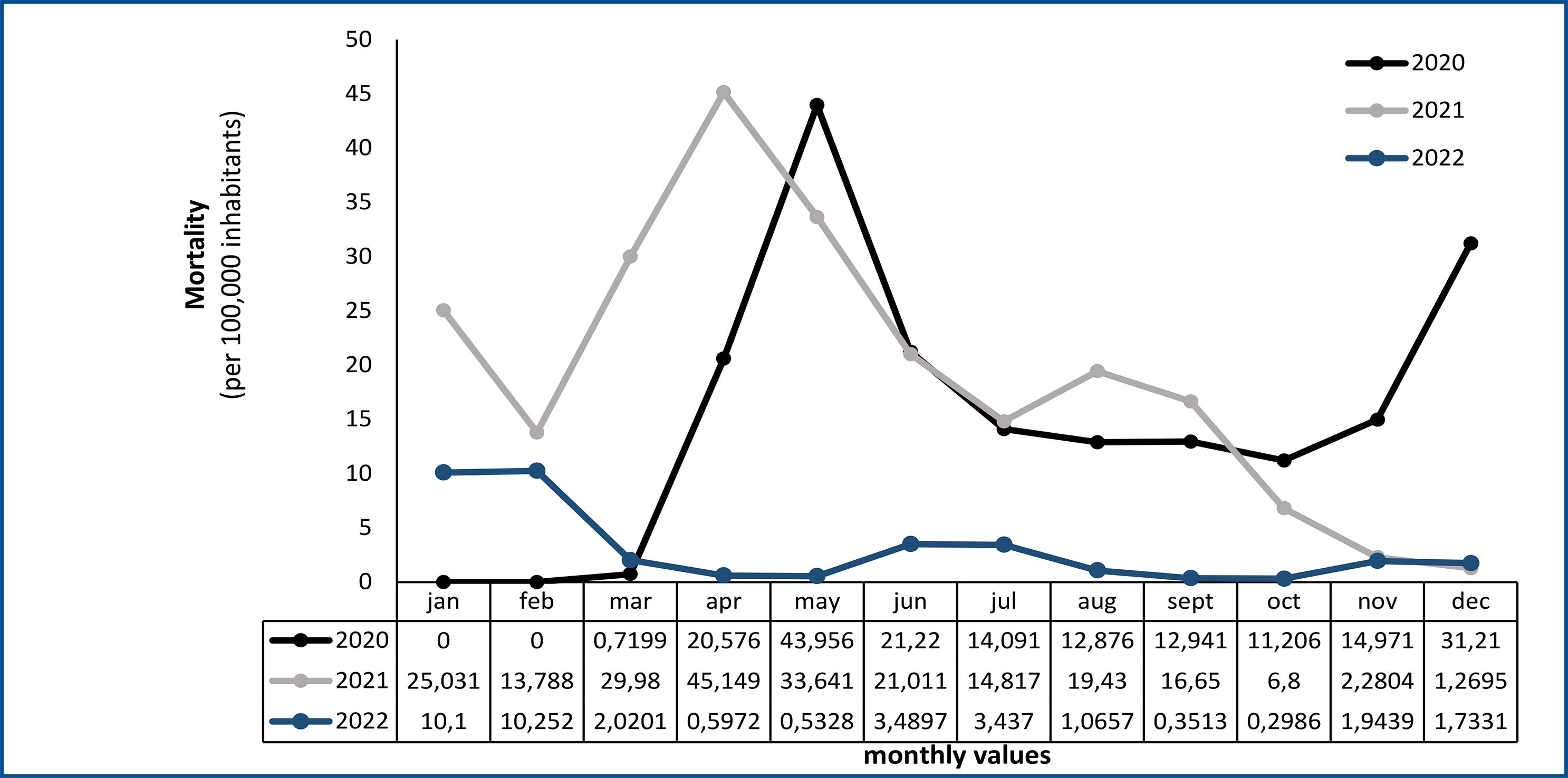

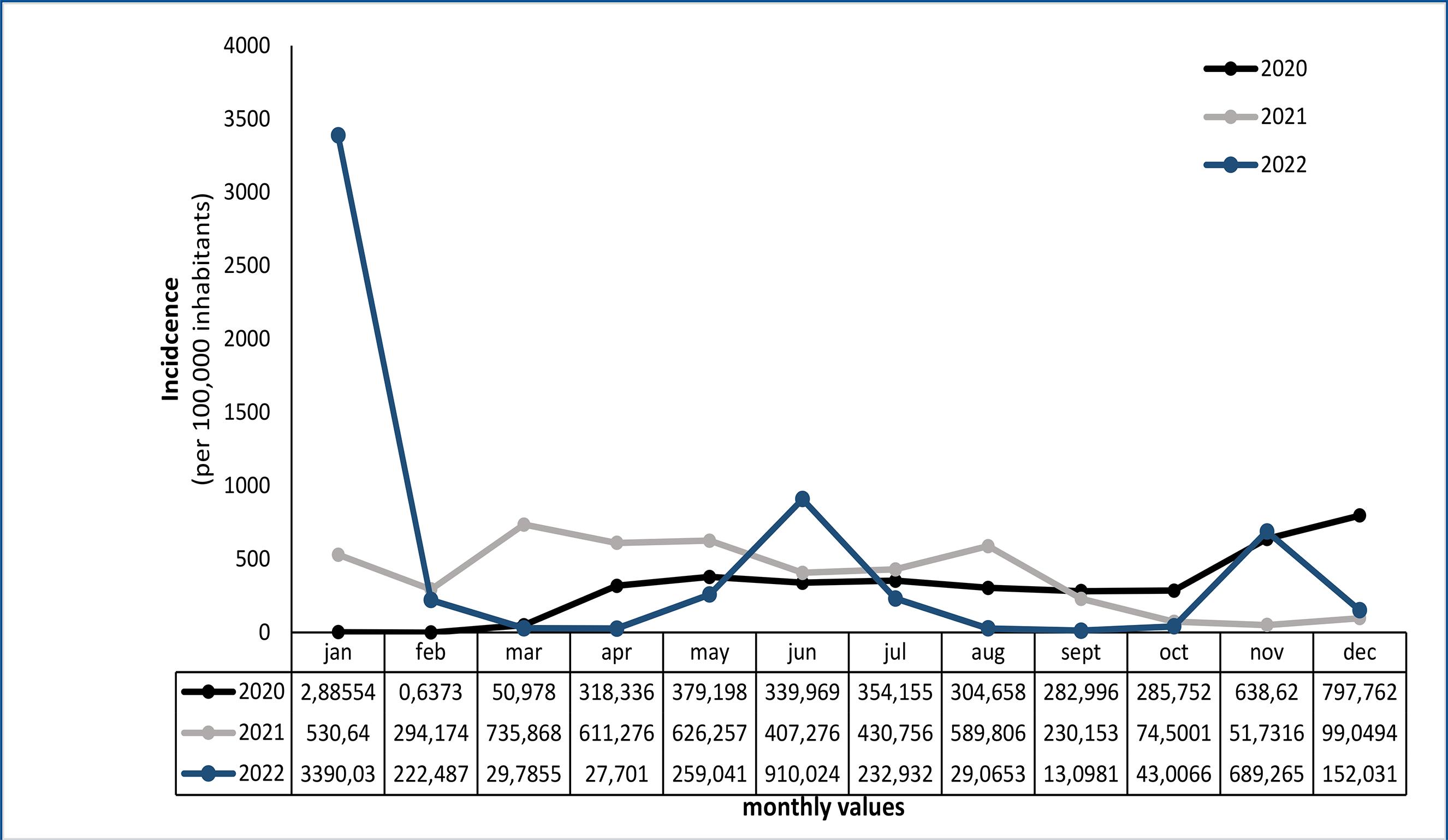

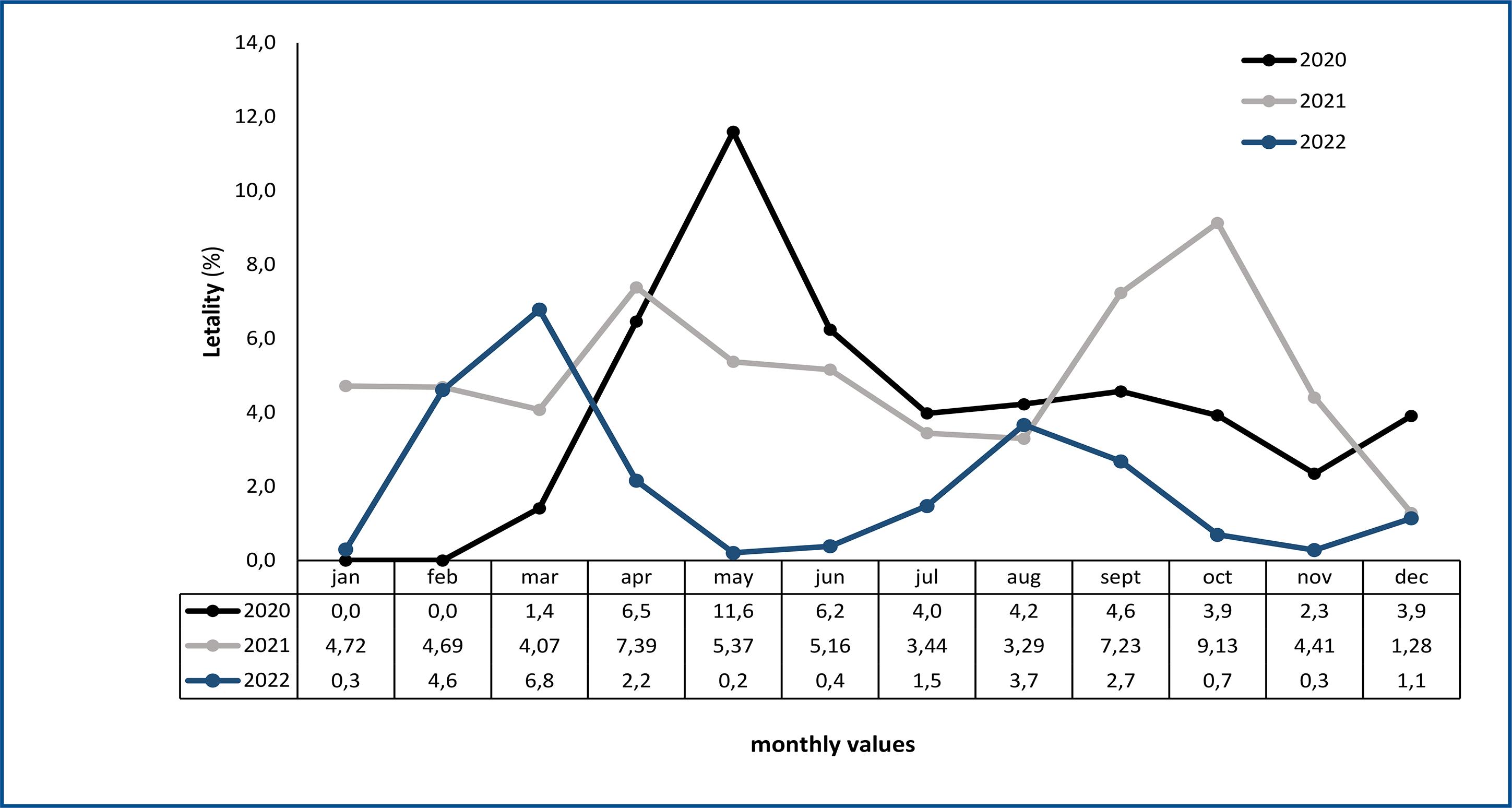

Figures 1-3 demonstrate and compare the time series of the incidence, mortality and lethality rates of COVID-19 by month and year in the state of Rio de Janeiro, between 2020 and 2022. The graphical analysis by month and year was inconclusive as to the existence of a trend. Statistical analyzes of daily percentage change rates (DPC) will be presented in Table 2, estimates by the linear regression technique using the Prais-Winsten method.

Figure 2 : Monthly time series of COVID-19 mortality in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, 2020-2021.

Figure 1 : Monthly time series of the incidence of COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, 2020-2021.

Figure 3 : Monthly time series of COVID-19 lethality in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, 2020-2021.

Table 2 : Estimates from the Prais-Winsten regression and daily change variation (DPC) of the death rate, lethality and incidence of COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, 2020 – 2022.

| RATE/YEAR | LINEAR REGRESSION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | CPD | (CI95%) | P | Trend | |

| INCIDENCE | |||||

| 2020 | 0.0087457 | 2.03 | 1.13; 2.94 | <0.001 | Growing |

| 2021 | -0.002439 | -0.56 | -0.91; -0.21 | 0.002 | Descending |

| 2022 | -0.003361 | -0.77 | -2.04; 0.51 | 0.237 | stationary |

| MORTALITY | |||||

| 2020 | 0.0045185 | 1.05 | -0.04; 2.14 | 0.058 | stationary |

| 2021 | -0.003558 | -0.82 | -1.15; -0.48 | <0.001 | Descending |

| 2022 | -0.002272 | -0.52 | -0.91; -0.13 | 0.009 | Descending |

| LETHALITY | |||||

| 2020 | -0.000526 | -0.12 | -0.35; 0.11 | 0.300 | stationary |

| 2021 | -0.000654 | -0.15 | -0.32; 0.02 | 0.084 | stationary |

| 2022 | 0.000631 | 0.15 | -0.38; 0.67 | 0.584 | stationary |

β – regression coefficient; P – p-value; DPC – daily percent change; 95%CI - 95% confidence interval.

No seasonal pattern or cyclical fluctuations that tend to repeat themselves at certain times of the year were observed. Random or unpredictable fluctuations occurred over time, without following a consistent pattern, determining important irregular peaks and valleys, however, the points are dispersed non-uniformly.

Table 2 presents the daily variation estimates obtained by Prais-Winsten linear regression to assess the trend in incidence, mortality and lethality rates due to COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro between 2020 and 2022. The incidence of COVID-19 19 in Rio de Janeiro peaked in 2020, with a trend towards significant growth (DPC = 2.03%) this year, followed by a deceleration in the following years. In the same year, mortality remained stable, but subsequently declined from 2021 onwards, with a CPD of -0.82% (p<0.001) in 2021 and -0.52% (p=0.009) in 2022. For lethality , the estimates indicate the absence of a significant trend throughout the analyzed period, characterizing stationarity.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the temporal variations of the lethality, mortality and incidence rates of COVID-19 in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The initial records of COVID-19 occurred in January 2020 and presented a percentage of 0.08% in the analyzed year. Cumulative data of confirmed cases, from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2022, recorded the highest incidence in the year 2020 with a daily growth of 2.03%. In 2021 and 2022, there was a change in behavior, which is decreasing (-0.56%) and stationary (-0.77%).

With regard to deaths, the month of May 2020 and 2021 maintained similar behaviors and the highest frequency occurred in 2020 with 23.92%. In the same year, a stationary trend for mortality was observed and in subsequent years the serial correlation remained decreasing, -0.82% and -0.52%, respectively. The fatality rate of 11.6% was the highest of all the years analyzed and the trend of this epidemiological measure remained stationary during the three pandemic years.

Other researchers demonstrated that the studied health indicators presented similar serial correlation parameters in other Brazilian states 15,16 . Some years of mortality, lethality and incidence indicators did not show statistical significance during the analysis of the temporal trend, however the values presented are important for planning at the state level to propose measures to reduce or stabilize the number of cases and deaths. This result corroborates the findings of a study conducted in the state of Piauí17.

The first cases of COVID-19 started on March 6, 2020 and Rio de Janeiro was the second state in the country to report confirmed cases18-20. At the beginning of the pandemic, there was a variation in the number of cases and deaths per day in the state, as well as in the country. Because it is a new disease and the biological behavior of the virus is still unknown, health services had to organize themselves regarding the implementation of the distribution network for diagnostic tests21,22.

However, the late adoption of non-pharmacological intervention measures highlighted the most critical phase of the pandemic, which was marked by the collapse of the health system and the occurrence of localized health crises, combining a lack of equipment, supplies for the ICU and exhaustion of the ICU workforce. health23,24.

The intensification of the measures raised would postpone the collapse of health services, reducing the infection rate and the number of deaths23,24. Such evidence could be observed in other states and countries, especially in China, which was successful in using non-pharmacological sanitary measures to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in the country and these measures have a direct impact on the lethality rate17,25,26.

A stationary phase of cases was observed between April and August 202027 . On the other hand, the incidence showed a significant increasing behavior in the year 2020, mainly in the months of November and December. According to Santos et al28, the same upward trend was observed, especially in December 2020, with 562.56 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Other disease peaks were observed in this research in March 2021 and January 2022.

It should be noted that carelessness with health policies, reduction in levels of social distancing, isolation, quarantine, relaxation of mobility restriction measures, especially in the months of November and December 2020, associated with holidays and some important national events, such such as elections, year-end celebrations, including Christmas and New Year, and even Carnival possibly resulted in a new increase in cases in these periods27,29.

Between March and June 2021, there was an abrupt increase in the number of cases and deaths in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In March 2021, peaks in cases and deaths were correlated with crowds celebrating Carnival festivities, even though the event was canceled9,16.

The ratification of measures capable of reducing the spread of the virus was the responsibility of city halls30. However, stricter measures had to be implemented and, through Decree No. 48,500, of February 4, 2021, specific rules were established aimed at protecting the health of the population, aiming to reduce the speed of contagion by COVID-19 with the prohibition of carnival and similar events31. Brito et al.32, corroborate the findings and observed the same movement in other Brazilian states.

In the most intensified moments of the pandemic, massive informal events outside health safety standards were reported. And additional inspection actions could have contributed for the established norms to be complied with18. It was in this context that the rapid growth and predominance of new Variants of Interest (VOIs) occurred, reaching its peak in April 2021, with high values of cases and deaths from March to June of the same year33. The Southeast region, in turn, was fundamental for the emergence and rapid dissemination of Sars-CoV-2 VOIs in the country27.

Rio de Janeiro is one of the states that make up this region and, as it is a national metropolis, it is considered an important entry point for international travelers due to its tourist attractions known worldwide, which may have contributed to the insertion of the virus in the territory34, 35.

Ribeiro et al., 9 , corroborate the findings and point out that air flows contributed to the importation of the virus into the state of Rio de Janeiro, just as the road flow also played an important role in the spread of COVID-19 throughout the state of Rio de Janeiro. This fact was due to the state’s high connectivity with other urban centers34,35.

During the pandemic period, Rio de Janeiro had an accumulated 449.93 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. These data are similar to those presented by the Brazilian Ministry of Health for the period from February 26, 2020 to December 31, 2022, in which the rate was 440.6 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, which is the highest in the country for the region of this study36.

When stratifying the research data, it was observed that the mortality rate was lower in March 2020 and February 2021, and higher in May and December 2020. In a study carried out in the city of Rio de Janeiro, The mortality rate in the state was lower in March 2020 (0.70 deaths/100,000 inhab.) and February 2021 (7.98 deaths/100,000 inhab.) and higher in May (41.62 deaths/100,000 inhab.) 100,000 inhab.) and December 2020 (24.48 deaths/100,000 inhab.)28.

Deaths were concentrated between April and June 2020 and 2021, respectively. The year 2022 did not follow this same pattern, with a higher concentration between January and February. An uncontrolled dissemination is observed, a behavior that was related to the pandemic response model18. And it can be justified by access to health care, socioeconomic and demographic conditions, and factors intrinsic to the population, such as age, lifestyle, comorbidities, among others15.

The highest lethality rates (8.3%) were described in Rio de Janeiro37 and the presented data validate the findings of this research. The high values of this indicator express important flaws in the health system, which may suggest lower diagnostic capacity of the local health network, slowness in identifying the disease in vulnerable groups, limited access to more complex services and care, political scenario, targeted testing to the most severe cases and with more deaths30,38.

There is no evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic is fully under control in the state of Rio de Janeiro, since the new coronavirus has not spread homogeneously and simultaneously in the state. It was possible to observe high averages of confirmed cases in most months and years compared during the analyzed period.

However, the divergent pattern between incidence and mortality suggests that, despite the continuity of viral transmission, there has been progress in the care and treatment of critically ill patients, resulting in a decrease in mortality. The stabilization of lethality indicates an improvement in the capacity for hospital care and therapeutic procedures over the period.

The national response to the COVID-19 pandemic maintained a close relationship between policy and public health with ups and downs in a continuous learning curve process. Rio de Janeiro decreed social isolation and voluntary quarantine, there was an early easing of sanitary measures, favoring a further increase in cases.

The rigidity and duration of health interventions, as well as the actions of leaders to apply measures for the prevention, surveillance and control of COVID-19 must be continuous and are fundamental in the pandemic. In addition, an effective and balanced approach is important to mitigate the impacts caused on the health, economy and well-being of the population.

The study has inherent limitations to the information analyzed due to records in the information system and even considering underreporting, these are the best data available for the formulation of public health policies and that define strategies to deal with and control the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, the method and the analysis applied in the study cannot infer causality, in addition to the individual variables not being considered, thus limiting the research conclusions. The time series regression model used in this work made it possible to quantify the percentage variation in the daily change in incidence, lethality and mortality rates, ensuring the assessment of daily changes in the dynamics of the pandemic in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

CONCLUSION

Based on the divergent trends observed through the daily temporal variations for the incidence, mortality and lethality of COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro between 2020 and 2022, it can be concluded, from an epidemiological point of view, the transmission of the coronavirus (measured by the incidence ) had an initial peak in 2020, with subsequent partial control resulting in a deceleration in the following years. Health care measures were able to keep mortality under control after the initial peak of 2020, despite subsequent waves of infection. The capacity for hospital care and adequate treatment has evolved, resulting in stabilization/reduction of lethality in the years analyzed.

The divergent behavior of the indicators suggests a combination of factors that influenced the epidemiological dynamics in a complex way over the period, and may have impacted the health indicators that were not homogeneous and showed different behaviors in the three years analyzed. The pandemic is not yet over in Rio de Janeiro and surveillance, prevention and assistance measures are still necessary.

texto em

texto em