INTRODUCTION

Obesity in adolescence has been interpreted as one of the significant public health challenges in the XXI1 century due to the phase being marked by different biological, cognitive, emotional, and social transformations characterized by the transition from childhood to adulthood2. Strategies to prevent overweight and obesity and treatment become even more complex because the need marks the cycle for autonomy and independence in daily activities, responsibility for ‘one’s health, and adherence to new habits and behavior3,4. It is essential to make and direct actions that aim to reduce obesity rates. For that reason, it is necessary to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease. In turn, the condition is a multifactorial disorder with prevalence attributed to various biopsychosocial processes, besides the influence of the environment in which the individual live5,6. Factors such as genetic predisposition, psychological conditions, physical inactivity, and inadequate feeding7 are related to excessive weight gain in early life, associated with social discrimination, behavior and learning problems, and negative self-image that persists in adult life8.

Since March 2020, the world has been facing the most significant pandemic and the first in the globalized world9, the Coronavirus (COVID-19). In this context, research is unanimous in showing that children and adolescents are more likely to develop psychiatric disorders resulting from the pandemic, and social isolation is established as a measure to contain the contagion of the SARS-CoV-210,11 virus. During social isolation, individuals in this age group are less exposed to the sun and practice less physical activity12, which is associated with negative states of emotion. At the same time, they consume more social media, which is also related to adverse conditions and mood13.

The literature presents multi-professional interventions - physical exercise, nutritional education, and psychotherapy - as an effective standard procedure for directing changes in behavior that result in a healthier lifestyle14,15. The indicated interventions involve multicomponent behavioral approaches through the participation of professionals in medicine, nutrition, physical education, psychology, physiotherapy, and biomedicina16.

Regarding these multi-professional programs, the study by Silva et al.17 states that, because they believe that interventions could lead to weight loss, participants develop many expectations regarding dietary changes and lifestyle habits to understand and validate the importance of having a nutritionally adequate diet and a physically active life. In addition, the same study showed that participants changed their initial perception of health at the end of the program, considering the concept more broadly, reporting improvement in sleep quality, activities, and an increase in social coexistence.

The literature suggests a strong relationship between obesity in adolescents and withdrawal from supervised exercise programs18. Considering that adherence has a significant influence on the results of weight lo19, unexpected or negative results can be at least partially attributed to the high evasion observed in this public20. Several biological and psychosocial barriers hinder adherence to behavioral interventions21. Given the above, this study aimed to describe the motivations of overweight adolescents participating in a multidisciplinary health promotion project (in order to align interventions with these expectations and improve adherence to similar programs).

METHODS

Study Location and Period

The research was conducted from March to July 2021 at our University in Southern Brazil.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

Adolescents who presented the following inclusion criteria were accepted: a) the ones who presented a picture of overweight or obesity according to the Body Mass Index (BMI), calculated using stature and mass measurement, and then converted it to standardized BMI z-scores following the international Obesity task force (IOTF) classification22; b) the ones aged between 10 and 19 years - following the chronological limits defined by the World Health Organization23.

The inclusion criterion covered participation in a multidisciplinary health promotion program of 12 weeks conducted by a team containing nutritionists, physical education professionals, psychologists, and physiotherapists.

Data Collection

The Sanny, Standard brand stadiometer measured height (cm); and body mass (kg), was measured using the InBody 570 bioimpedance equipment (InBody, Body Composition Analyser, South Korea). With the data on height and body mass, the BMI was calculated through the equation proposed by Whegley and Quételet24. Through an anamnesis developed by the authors, it was obtained data such as date of birth, parents’ education, and socioeconomic status. From end to end, semi-structured interviews were performed - conducted by previously trained evaluators, being the same interviewer for the collection in the pre and post-intervention. To construct thematic categories was used Bardin25 content analysis. In this way, it was observed the three stages of the content analysis: (1) pre-analysis, which consists of the elaboration of initial ideas and creation of categories of analysis; (2) interpretation of the collected material and construction of the exploration categories; (3) data processing and construction of results.

The interviews included the following guiding questions:

a) What do you expect when participating in the program?

b) How is your relationship with food?

c) Do you like physical activity? Practice? What?

The collections were conducted between March to July 2021. Participants answered the interview in person two times (before and after the intervention period of 12 weeks). All interviews were recorded with the interviewee’s consent and later transcribed in full by the researchers using the Microsoft Word (version 2021, Microsoft, The United States of America).

Interventions

Participants performed the interventions three times a week for 12 weeks, guided by a team of physical education, nutrition, and psychology professionals. Physical exercise was performed 3x a week for 1 hour a day and organized into aerobic and anaerobic exercises; theoretical and practical classes related to nutritional education and psychotherapy were conducted 1x a week each during 30 minutes. In groups, through an approach focused on awareness and change in eating, carried out behavior Nutritional education interventions. The themes are based on the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population26.

Weekly meetings were held with theoretical-practical activities, using materials and dynamics to be performed in time and space. These are some of the topics reported: application of the 24-hour recall; guidance for filling out the 3-day food record; 10 steps of the Food Guide and healthy plate; adequacy of macro and micronutrients; adequate and balanced diet; level of food processing; guidance on home measures; food preparation and meal frequency; eating behavior; reading labels; myths and truths about ultra-processed foods; techniques to maintain healthy eating after the program. It is worth mentioning that interventions are always conducted to guide a balanced diet. Therefore, It was not prescribed any diet to adolescents.

On the other hand, psychoeducation interventions were performed in the approach of operative groups27and took place through theoretical-practical and vigorous activities aimed at the interaction of participants. The themes of the interventions were defined from the initial meetings, looking around and the needs of the group, using as support the values and principles of the National Health Promotion Policy (PNPS)28. In this way, the individual subject will be considered in the collective issue, taking into account each historical, political, social, and familiar27,29. It was conducted the weekly meetings based on topics such as: objective and functioning of interventions; understanding the body; actual weight loss; establishing short, medium, and long-term goals; health as a criterion for choices (exemplifying what it is to “lose weight” in an unhealthy way and what the consequences are); the importance of learning to enjoy the process; behavioral tasks for the week; self-esteem and self-confidence; standards of beauty and healthy beauty; bullying; healthy habits in improving psychic and emotional states; creating fun and healthy rituals; how to share project learning with family and friends; time management itself and healthy leisure choices; analysis of goals and the changes obtained from various aspects; self-comparison; persisting with healthy habits for life.

The physical exercises were conducted as a circuit, emphasizing large muscle groups. Thus, the sessions were divided into A/B training and performed alternately, focusing on large muscle groups, strength and muscular endurance, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness.

Data Analysis

The data obtained in the transcription of the interviews were analyzed means by the software QSR NVivo 11, Windows version, using the content analysis technique of Bardin25. The program allowed us to store interviews, cross-check information, encode data and manage research, and assist in assembling thematic categories. In addition, it also enabled the primary statistical analysis and grouping of speech into clusters, trees, and word frequencies.

Ethical and Legal Aspects of the Research

The Ethics and Research Committee (ERC) approved the research under opinion number 4.913.453/2021. The researchers followed the resolution 466/2012 from the Ministry of Health of the Brazilian Government. The interviews were recorded and transcribed in their entirety with the authorization of the participants. All subjects were informed of the study procedures and the possible risks and benefits. Participation in the program was conditional on signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF) by the parents and the adolescents’ Consent Form (CF).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The final sample comprised 24 adolescents with the following characteristics: a mean age of 13.8 years old, 62.5% (15) female, and 37.5% (9) male. The participants’ mean BMI was 31.8 kg/m2. Regarding family income, 29.16% had a monthly payment of one to three minimum wages, 41.66% had a monthly income of 3 to 6 minimum wages, and 29.18% had a monthly income greater than six minimum wages. Regarding parents’ educational level, 70.83% of mothers had completed higher education, while 29.16% had completed high school.

The characteristic of the socioeconomic level found in the sample confirms data already established in the literature on overweight in adolescents being more frequent in families with better socioeconomic conditions in developing countries30. However, the sample heterogeneity in this aspect supports that, in Brazil, this growth occurs in all socioeconomic strata, including among families with lower purchasing power31. Regarding the parents’ schooling, we observed a significant majority of mothers with complete higher education, corroborating with the study of Guedes and collaborators32, which followed that children are three times more likely to develop overweight/obesity when parents have higher education.

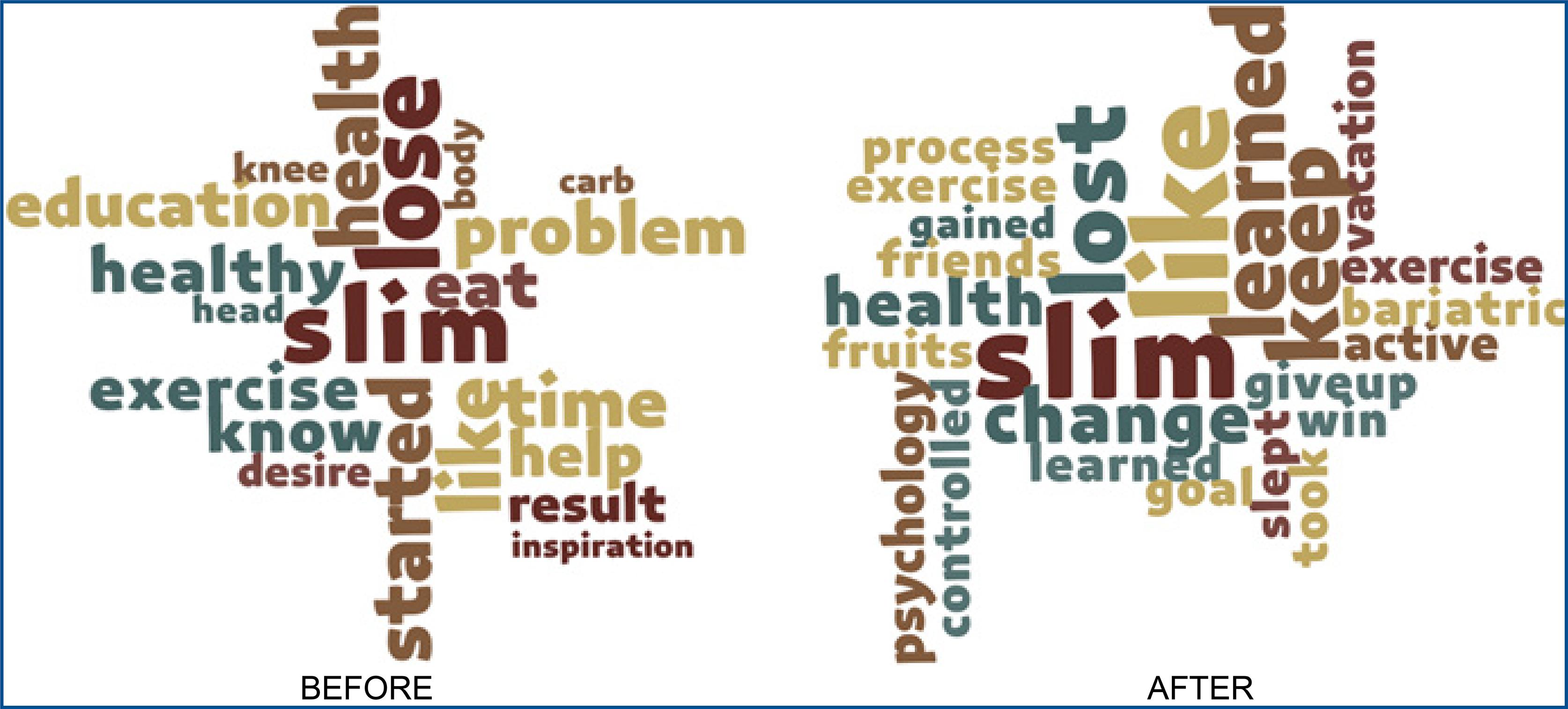

Based on the similarities found in transcription and other contents during the analysis process, the following categories emerged: (1) motivation, (2) food, and (3) physical activity. The results were presented through word clouds, where we can observe the frequency of specific terms in the participants’ discourse and associations. The size of the word in the figure accuses its representativeness. In the category 1 case (motivation), a higher frequency and representativeness of the word “slim” appeared before and after the intervention. To a lesser extent, the term “health” also appears in both moments.

The above result shows that the subjects had weight loss as the primary motivation to participate in the multidisciplinary program. The lower representativeness of the word “health” is justified by adolescents limiting health to thinness, a distorted definition possibly supported by a low degree of health literacy33. This one, in turn, is a worrying factor because, according to Berkman and collaborations34, the degree of health literacy is a strong indicator of the actual state of health of the individual. Because they are overweight or obese adolescents, overvaluing weight loss as the primary indicator of health suggests a specific psychological vulnerability of these individuals since excess fat results in low self-esteem, high body dissatisfaction, and behavioral disorders35.

In turn, at the time post-intervention, the word “slim” is accompanied by words such as “learned,” “keep,” “change,” and the verb “lost” now appears in the past (figure 1), interventions were effective to broaden the concept of health and self-perception of participants. In addition, it was possible to conclude that, although this is not the initial motivation, adolescents realized the need to adopt the good habits they learned in the interventions to be physically and mentally healthy, broadly and not only according to the simplistic definition of the absence of disease.

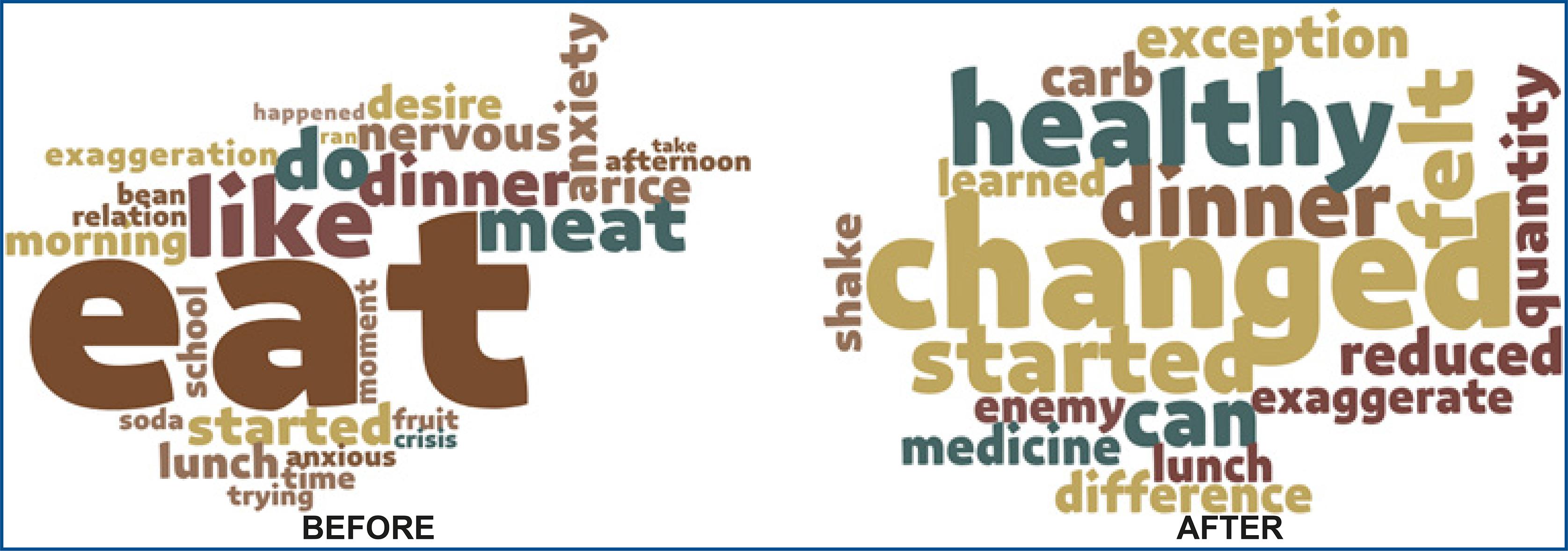

Regarding category 2 (food), the word cloud refers to the pre-intervention moment manifested with greater representativeness of the word “eat,” associated with words such as “like,” “anxiety,” “nervous,” “exaggeration,” and “crisis” (figure 2). The result revealed at the pre-intervention indicates that, despite enjoying eating, the act was associated with feelings such as anxiety and nervousness for adolescents. It may be the cause of crises and exaggerations during the meal. This sequence of events happens because food is seen as gratification or a form of compensation and numb emotions36. For that reason, these events are connected with the food.

In the pre-intervention moment, it was not possible to identify less representative words yet, such as “time,” “moment,” and “ran,” used to represent how made meals at home. In this situation, many reported factors such as lack of time and excessive dedication to work by parents. In previous studies, this reality motivated the increased consumption of nutritionally inadequate foods and the omission of the main meals because the parents presented a more negligent posture with food issues37,38.

While in the post-intervention period (figure 2), the words: “changed,” “healthy,” “learned,” and “exception” suggest that adolescents acquired theoretical and practical knowledge about the theme during the project, which demonstrated the effectiveness of nutritional education and psychotherapy strategies in changing behavior about alimentation39. Silva, Frazão, Osório, and Vasconcelos40 studies concluded that adolescents’ adherence to healthy eating is associated with some aspects as: liking some healthy foods, having access to and availability of these foods, being afraid of becoming fat, receiving encouragement from the media and the family environment, as well as from school through educational feeding practices, that confirm the importance of programs aiming nutritional education in this age group.

Finally, the analysis of category 3 (physical exercise) shows that at the time before the interventions, the words with more excellent representation were “make” and “like,” individuals with the practice of physical activity. However, there is a highlight for some modalities such as “walk,” “soccer,” “swimming,” “run,” “gym,” “basketball,” and “dance,” activities and/or practiced in community environments. Due to the social isolation imposed by the COVID-1911 pandemic, some actions had to paralyze. These explain the high increase in body weight in adolescents during the period41. That is why the words were replaced by other modalities like: “walk,” “bike,” and “treadmill” at the time after the intervention.

These activities are practiced individually, without needing more significant interactions, and in environments with greater privacy, such as the house, yard, and street. The picture mentioned above, together with the expressive representation of the word “pandemic” in the post-intervention moment, highlights the reflection of the period of social isolation experienced by the COVID-19 pandemic, in which individual modalities and tele-exercices41 were encouraged.

The research conducted by Carneiro, Medeiros, and Silva42 reinforces the results found in this study, highlighting that actions developed in an interdisciplinary project aimed at obesity can lead to a significant experience in health promotion and behaviors concerning unhealthy habits. In addition, intervention programs can support the public and private health system in managing obesity, minimizing expenditure in the sector resulting from treating obesity and associated comorbidities43.

Despite the School Health Program44, to encourage the necessary training of students through actions of health promotion, disease prevention, and health care of children, adolescents and there are difficulties in the execution of interventions for this purpose in school environments, such as lack of material and human resources, and lack of training for the professions45,46. The framework mentioned above reinforces the importance of research and extension projects that overcome this demand, providing support and care to vulnerable communities - especially in times of overload of the public system, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic47, being indispensable to establishing the link between university and society48.

The study limitations consist of: (1) difficulty in obtaining complete answers from adolescents during the interviews; (2) absence of a control group; (3) high dropout rate (43%) for various reasons such as difficulty in locomotion, lack of identification, and conflicting schedules.

As strengths of the study, we can highlight: (1) qualitative methodology that allowed to analyze of subjective aspects of the participants; (2) adequate intervention time according to Jensen et al,.49. The suggestion is that future research is performed with a larger sample and compare the results obtained with a control group.

CONCLUSION

Regarding the categories of analysis, it identified that the subjects’ motivations to participate in the program focused on the possibility of weight loss, which is a limited perception of health. However, the final interviews indicated that the interventions effectively expanded the participants’ health concepts. Regarding food, the discussions made it possible to understand that, at an early stage, adolescents associate the act of eating with feelings such as anxiety and nervousness. At the end of the program, it was possible to notice that adolescents acquired theoretical and practical knowledge about the subject, which confirms the effectiveness of nutritional education and psychotherapy strategies in changing behaviors related to food. The responses related to the category of physical exercises demonstrated a change in the modalities practiced by the participants, possibly due to the social isolation framework installed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results reinforce the importance of understanding adolescents’ perceptions about their health and related habits to develop effective strategies focused on preventing and treating obesity through health promotion.